Kenneth M. Pollack's Blog, page 10

November 6, 2012

A Series of Unfortunate Events: A Crisis Simulation of a U.S.-Iranian Confrontation

[image error]The potential for confrontation between the United States and Iran, stemming from ongoing tensions over Iran’s nuclear program and western covert actions intended to delay or degrade it, remains a pressing concern for U.S. policymakers. The Saban Center for Middle East Policy hosted a one-day crisis simulation in September that explored different scenarios should a confrontation occur.

The Saban Center's new Middle East Memo, A Series of Unfortunate Events: A Crisis Simulation of a U.S.-Iranian Confrontation, authored by senior fellow Kenneth M. Pollack, presents lessons and observations from the exercise.

Key findings include:

• Growing tensions are significantly reducing the “margin of error” between the two sides, increasing the potential for miscalculations to escalate to a conflict between the two countries.

• Should Iran make significant progress in enriching fissile material, both sides would have a powerful incentive to think short-term rather than long-term, in turn reinforcing the propensity for rapid escalation.

• U.S. policymakers must recognize the possibility that Iranian rhetoric about how the Islamic Republic would react in various situations may prove consistent with actual Iranian actions.

Downloads

Download the paper

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Image Source: © Fars News / Reuters

October 23, 2012

Reading Machiavelli in Iraq

Most Americans know Niccolò Machiavelli only from The Prince, a sixteenth-century “audition tape” he dashed off in lieu of a résumé to try to land a job. It’s a shame. Not only was Machiavelli the leading advocate of democracy of his day, but his ideas also had a profound influence on the framers of our own Constitution.

It’s even more of a shame because the corpus of Machiavelli’s remarkable work on democracy, politics and international relations is easily the best guide to understanding the dynamics at play in contemporary Iraq and its situation within the wider Middle East.

Iraq today is a place that Machiavelli would have understood well. It is a weak state, riven by factions, with an embryonic democratic system increasingly undermined from within and without. It is encircled by a combination of equally weak and fragmented Arab states as well as powerful non-Arab neighbors seeking to dominate or even subjugate it. Iraq’s democratic form persists, but its weakness, combined with internal and external threats, seems more likely to drive it toward either renewed autocracy or renewed chaos. It cries out for a leader of great ability and great virtue to vanquish all of these monsters and restore it to the democratic path it had started down in 2008–2009.

That course seems less and less likely with each passing month, and it may take a true Machiavellian prince—one strong and cunning enough to secure the power of the state but foresighted enough to foster a democracy as the only recipe for true stability—to achieve it. Unfortunately, in all of human history, such figures have been rare. It is unclear whether Iraq possesses such a leader, but the reemergence of its old political culture as America’s role ebbs makes it ever less likely that such a remarkable figure could emerge to save Iraq from itself.

Read the full article at nationalinterest.org »

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: The National Interest

Image Source: © Saad Shalash / Reuters

September 24, 2012

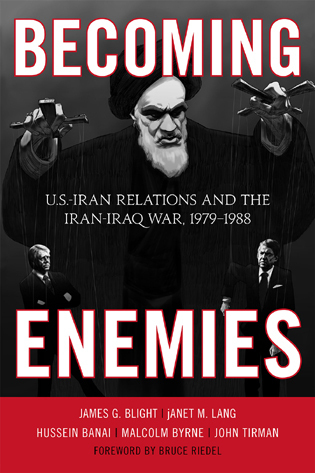

Becoming Enemies: U.S.-Iran Relations During the Iran-Iraq War

Event Information

September 24, 2012

12:30 PM - 2:00 PM EDT

The Brookings Institution

1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW

Washington, DC

History is a pivotal tool in strengthening U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East. At a time of heightened tensions with the Islamic Republic of Iran, it is essential that we understand and learn from our past experiences with Tehran.

[image error]On September 24, the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings hosted a discussion focusing on the book Becoming Enemies: U.S.-Iran Relations During the Iran-Iraq War, 1979-1988. Written by Assistant Professor Hussein Banai of Occidental College, Professors James Blight and Janet Lang of the Balsillie School of International Affairs, Executive Director Jon Tirman of MIT’s Center for International Studies, Deputy Director Malcolm Byrne of the National Security Archive, and Senior Fellow Bruce Riedel of the Saban Center, the book employs critical oral history as a means for detailing the complete scope of the American-Iranian relationship, from the fall of Mohammad Reza Shah in 1979 through the first Gulf War. The book also focuses on individuals that were part of the American decision-making matrix at the time, and captures their firsthand accounts and pivotal documents which detail the United States’ policy during a formative time in Middle Eastern history.

Hosted by Saban Center Senior Fellow Kenneth Pollack, the discussion focused on the findings of the book, and examined how best to learn from U.S. foreign policy missteps of the past. Framing the discussion, Pollack stressed that the events of the Iran-Iraq War from 1980-1988 set the stage for what we see in the Middle East today. Prior to this conflict, the United States maintained a policy of neutrality in the Persian Gulf. Pollack assessed that during the course of the war, the United States found itself involved in the events of the Persian Gulf in unforeseen ways. The events of this war forced the United States to begin thinking about the internal politics of Iran and Iraq, which policymakers almost steadfastly refused to do so beforehand. Connecting history to contemporary times, Pollack identified the nuclear proliferation problem we see today as an explicit function of the Iran-Iraq War. The war revived Iranian nuclear aspirations which remain a primary topic of debate in the upcoming U.S. elections.

Leading off the discussion among the authors, Riedel stressed that history congruently rhymes with contemporary conflicts. Agreeing with Pollack’s assessment, Mr. Riedel also saw the United States as merely an observer in the initial phases of the Iran-Iraq War; however, the United States quickly morphed into a co-belligerent on the side of the Iraqis. Riedel described the book’s unique collection of insider views, extraordinarily significant documents, and expert commentary detailing the thought process behind U.S. foreign policy. Riedel focused his commentary on six distinct lessons that America must learn from the Iran-Iraq War: Iran is a difficult country to intimidate and leverage; Iran is not a suicidal state, although it may employ the concept and practice of martyrdom to pursue foreign policy goals; ending the Iran-Iraq War turned out to be much harder than anticipated; the advice given to the United States by its allies in the Middle East was consistently catastrophic; the United States should not have expected any gratitude when the war culminated, and, rather, should have been prepared for blame from all sides. Riedel emphasized the overarching historical message behind the events of the Iran-Iraq War, namely that any war with Iran will be an exhaustive, destructive, and precarious undertaking. Iran will not surrender easily, and the threshold for relative peace was set dangerously high during the Iran-Iraq War. Any future conflict with the Iranians involving nuclear weapons would be amazingly ugly.

Lang detailed the critical oral history component of the authors’ research. Lang described how this type of oral history seeks to choose foreign policy failures of the past that have strong relevance to contemporary U.S. policy decisions. Lang detailed three essential components of gathering critical oral history: seeking the recollections of those involved firsthand in the decision-making apparatus, the significance of hard documents which can create a “time machine” to go back in history, and the input of scholars to complete the research. Lang also stressed the need to find individuals whose curiosity trumps their fear, and are willing to openly discuss their historical missteps.

Blight, also focusing on the critical oral history process, described a conference in Italy in 2007 that provided a platform for those involved in the decision-making process to discuss their decisions during the Iran-Iraq War. Blight underlined the necessity for this type of context as a means to develop critical oral history: one that provides a platform for primary players to discuss their thought processes to individuals who will handle it responsibly. This type of “honest brokerage,” Blight emphasized, is a critical aspect of developing an effective critical oral history.

Byrne focused on the trove of illuminating documents discovered in the researching of Becoming Enemies, emphasizing the significance of documents in painting a comprehensive picture when historically examining the Iranian-American relationship. He described, in detail, a discovered CIA memo signed by then-Director Stansfield Turner on September 17, 1980, warning of an extremely near conflict. This example demonstrated the top-level awareness of the events happening on the ground. Byrne also detailed a document of then-Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s talking points after his first trip to the region in 1981, which included references to a discussion with Saudi officials in which it was suggested that Jimmy Carter gave Saddam Hussein a “green light” to invade Iran. Describing this as potential smoking-gun evidence, Byrne emphasized the political, psychological, and international relations ripples that can emanate from just a simple sentence. Lastly, Byrne described a State Department memo, “Analysis of Possible U.S. Shift from a Position of Strict Neutrality” that was released on October 7, 1983. Ironically, from July 1982 onwards, the United States had already shifted from a position of neutrality to what was essentially a position of co-belligerency on the Iraqi side. Byrne questioned the State Department’s thinking in producing this analysis when the policy had already seemingly shifted. Byrne concluded by underlining the necessity of exploring the documents of both sides. There is a wealth of material outside the American archival systems, and Byrne argued that in order to accurately construct a critical oral history, one must explore all perspectives.

Banai brought the discussion closer to the present day, referencing the Arab Awakening and its ripples throughout the region. Banai compared a revolution to a hurricane: not the organized chaos of war, but a force that enters town and replaces the known while leaving some debris and remnants of the old. Banai argued that the Iranian revolution was no exception, and that some of its after-effects are being brought to mind as the dust of the Arab Awakening is beginning to settle – particularly in Egypt and Tunisia. Banai described a steep learning curve in the beginning of revolutions; whenever a new regime takes power, young revolutionaries occupy positions they may not be completely qualified for. Furthermore, there are fixed offices and shifting personalities moving in and out. Particularly during the Iranian revolution, the Iranian political structure was very much in flux, and the United States intelligence apparatus attributed powers to the incorrect people, misjudging the personal relationships within the Iranian political sphere. These personality politics, compounded with a steep learning curve, presented the United States and Iran with very different foreign policies. When dealing with today’s reality, Banai insisted that understanding internal hierarchies and the domestic power dynamics in Iran is necessary. He also stressed the need to observe the actions, not the words, of the realists and the more ideologically driven revolutionaries. By examining these individuals through an analytical lens, Banai argued misconception could be minimized in any future conflicts.

During the question-and-answer segment of the luncheon, Riedel touched on the implications of the Iranian hostage crisis on U.S. foreign policy during the Iran-Iraq War. Riedel speculated that the United States’ hesitation in ending the Iran-Iraq War stemmed from its desire to seek revenge for the hostage crisis of 1979. He concluded the luncheon by reminding participants of how much it took to compel the Iranians to sign a ceasefire agreement. It took a myriad of Iraqi divisions crossing into Iranian soil, the United States’ continuous bombardment of Iranian airspace, and the realistic fear of a chemical weapon attack delivered via Scud missiles. Riedel stressed that, when thinking about a future conflict with Iran, policymakers must keep in mind this dangerously high set of standards. History does not always repeat itself, but by understanding the parallels between past and present, policymakers can make more calculated decisions with regards to the Islamic Republic of Iran and the rest of the Middle East during this time of great fluidity.

September 23, 2012

Simulated War Between U.S.-Iran Has Grisly End

Editor's Note: In an interview with NPR's All Things Considered, Kenneth Pollack spoke about a recent war game he conducted regarding the United States and Iran.

ROBERT SIEGEL, HOST: There was another exercise in Washington last week that involved Iran, the U.S. and the impasse over the Iranian nuclear program. The Brookings Institution staged a war game. No real weapons were used, but teams playing the roles of U.S. and Iranian policymakers were presented with a hypothetical but not very far-fetched scenario, and the results were not encouraging. Kenneth Pollack is a senior fellow in the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution, and he ran this exercise and joins us. Good to see you again.

KENNETH POLLACK: Very good to be back.

SIEGEL: First, you're not identifying the people who took part in the game, but can you at least describe what kind of people they were?

POLLACK: Sure. On the American side, we brought together of about a dozen former very senior American officials, people who have actually occupied the roles in reality that they were asked to play in the game. On the Iranian side, it was a little bit different. We obviously don't have access to, honest to goodness, former Iranian policymakers. So what we had to do there was rely on Iranian-American and American experts on Iran, a number of whom had some experience in the U.S. government, but obviously somewhat different from our American team.

SIEGEL: They are presented with this scenario that you wrote, which included cyber attacks, assassinations of scientists, and it escalated from there. When you wrote all of this, did you write it in a way that you thought it was at least possible that diplomacy might prevail over threats of war?

POLLACK: Absolutely. The idea was to test some basic hypotheses about where the United States and Iran might be going. And we allowed for the scenario to move in any of several dozen different directions, some of which were entirely pacific, some were entirely bellicose and others that were a mix of the two. And some of the interesting things that came out of the game was that there were some key moments were if one team or the other had done something slightly differently, according to the other team, they would've had a peaceful response instead of what actually happened.

Listen to the full interview at npr.org »

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: NPR

Image Source: © Morteza Nikoubazl / Reuters

September 11, 2012

Israel’s Security and Iran: A View from Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz

Event Information

September 11, 2012

9:30 AM - 11:00 AM EDT

Falk Auditorium

Brookings Institution

1775 Massachusetts Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20036

This event has reached capacity and registration is now closed. Media may contact Gail Chalef, gchalef@brookings.edu, for more information.

While Israel and Iran continue trading covert punches and overheated rhetoric, the question of what Israel can and will do to turn back the clock of a nuclear Iran remains unanswered. Some Israelis fiercely advocate a preventive military strike, while others press just as passionately for a diplomatic track. How divided is Israel on the best way to proceed vis-à-vis Iran? Will Israel’s course put it at odds with Washington?

On September 11, the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings will host Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz, the former commander-in-chief of the Israeli Defense Forces, for a discussion on his views on the best approach to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. Brookings Senior Fellow Kenneth Pollack will provide introductory remarks and moderate the discussion.

After the program, Lt. Gen. Haloutz will take audience questions.

August 9, 2012

The Syrian Spillover

The Syrian civil war has gone from bad to worse, with casualties mounting and horrors multiplying. Civil wars like Syria's are obviously tragedies for the countries they consume, but they can also be catastrophes for their neighbors. Long-lasting and bloody civil wars often overflow their borders, spreading war and misery.

In 2006, as Iraq spiraled downward into the depths of intercommunal carnage, we conducted a study of spillover from recent civil wars in the Balkans, the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere in order to identify patterns in how conflicts spread across borders. Since then, Iraq itself, along with Afghanistan, Libya, and Yemen, have furnished additional examples of how dangerous spillover can be. For instance, weapons from Libya have empowered fighters in Mali who have seized large swathes of that country, while al Qaeda-linked terrorists exploiting the chaos in Yemen launched nearly successful terrorist attacks on the United States.

Spillover is once again in the news as the conflict in Syria evinces the same dangerous patterns. Thousands of refugees are streaming across the border into Turkey as Ankara looks warily at Kurdish groups using Northern Syria for safe haven. Growing refugee communities are causing strain in Jordan and Lebanon. Meanwhile, the capture of 48 Iranians, who may be paramilitary specialists, could pull Tehran further into the conflict. Israel eyes developments in Syria warily, remembering repeated wars and concern over the country's massive chemical weapons arsenal. For the United States, these developments are particularly important because spillover from the civil war could threaten America's vital interests far more than a war contained within Syria's borders.

Read the full article at foreignpolicy.com »

Authors

Daniel L. BymanKenneth M. Pollack

Publication: Foreign Policy

Image Source: Goran Tomasevic / Reuters

How, When and Whether to End the War in Syria

“The beginning of wisdom,” a Chinese saying goes, “is to call things by their right names.” And the right name for what is happening in Syria — and has been for more than a year — is an all-out civil war.

Syria is Lebanon of the 1970s and ’80s. It is Afghanistan, Congo or the Balkans of the 1990s. It is Iraq of 2005-2007. It is not an insurgency. It is not a rebellion. It is not Yemen. It is certainly not Egypt or Tunisia.

It is important to accept this simple fact, because civil wars — especially ethno-sectarian civil wars such as the one burning in Syria — both reflect and unleash powerful forces that constrain what can be done about them. These forces can’t be turned off or ignored; they must be dealt with directly if there is to be any chance of ending the conflict.

So, how do these kinds of wars end? Usually, in one of two ways: One side wins, typically in murderous fashion, or a third party intervenes with enough force to snuff out the fighting. Until Washington commits to either helping one side or leading an intervention in Syria, nothing else we do will make much difference. The history of civil wars — and of efforts to stop them — demonstrates what is likely to work and what is likely to fail.

At the top of the list of initiatives that rarely succeed in ending a civil war on their own is a negotiated settlement. The likelihood that this could work without force to impose or guarantee an accord is slight. It’s why Kofi Annan’s mission as the U.N.-Arab League envoy was always likely to fail and why, now that Annan has announced his resignation, the effort should be cast aside as a distraction.

It’s also why the Obama administration’s fixation on Russia’s supposed leverage with the Syrian regime and the idea of a Yemen-style solution in which President Bashar al-Assad steps down are equally misconceived. Assad is unlikely to step down, because — like Radovan Karadzic, Saddam Hussein, Moammar Gaddafiand many others before him — he believes that his adversaries will kill him and his family if he does. And he is probably right.

Even if he did voluntarily leave office, his resignation or flight from Syria would probably be meaningless: The war is being led by Assad, but it is being waged by the country’s Alawite community and other minorities, who believe that they are fighting not just for their privileged place in Syrian society but for their lives. Were Assad to resign or flee, the most likely outcome would be for another Alawite leader to take his place and continue the fight.

The insistence that “Assad’s days are numbered” is not only probably incorrect, it is largely irrelevant. Throughout the Lebanese civil war of 1975-1991, there was always a man sitting in the Baabda Palace calling himself the president. And he had a military force that reported to him called the Lebanese Armed Forces. In truth, he was nothing more than a Maronite Christian warlord, and the remnants of the Lebanese Armed Forces had become nothing but a Maronite militia, yet the names persisted.

So Assad may not fall for some time, and he may continue to call himself the president of Syria. He may even be able to sit in an embattled Damascus, defended by a military formation still calling itself the Syrian Armed Forces. But that won’t make him anything more than the chief of a largely Alawite militia.

The dangers of picking winners

If the United States decides that it is in its interest to end the Syrian civil war, Washington could certainly decide to help one side win.

In effect, we’ve already done so. Not only has the Obama administration demanded that the Assad regime relinquish power, but numerous media reports say that the United States is providing limited covert support to the Syrian opposition. According to these reports, the aid is nonlethal — helping to vet fighters, providing some planning guidance.

What Washington has not done is give the opposition the kind of help that would allow it to prevail in short order. Right now, the standoff in Syria is about guns against numbers. The regime has a small pool of tanks, artillery, attack helicopters and other heavy weapons that allows it to beat back the opposition wherever such forces are committed. So whenever the opposition threatens something of great importance to Assad’s government — such as Damascus or Aleppo — the regime can stymie the attack. But the opposition’s numbers are growing, allowing it to take control of large swaths of territory that is of low priority to Assad.

Over time, and especially if its supply of replacements and spare parts from Iran and Russia can be choked off, the government’s stockpile of heavy weapons will diminish, and as the war becomes a contest of light infantry on both sides, the numbers of the opposition should begin to tip the balance.

The problem is that helping the opposition “win” might end up looking something like Afghanistan in 2001. Opposition forces may end up in control of most of the country, even Damascus, but the Alawites and their allies might be holed up in the mountains, continuing the fight. And as in Afghanistan, where the Northern Alliance held the Panjshir valleyfor years against the otherwise overwhelming force of the Taliban, so too might the Alawites be able to hold their mountainous homeland along Syria’s western coast for a long time.

The parallels are plentiful. The Syrian opposition is badly fragmented, with divisions within and between the political groups and fighting forces. In Afghanistan, after the Soviet departure in 1989, a similar situation was a recipe for internecine warfare. Indeed, the various mujaheddin groups fell to fighting one another even before the Soviet puppet regime of President Najibullah fell —allowing the regime to survive until the Taliban crushed Najibullah and the mujaheddin alike.

In Syria, the dominant force that might emerge from an opposition takeover could be the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. The group, living for decades under persecution from the Shiite-dominated Syrian Baath Party, is a very different creature from the Brotherhood parties that have taken power in Egypt and Tunisia. It is an old, unreconstructed, hard-line, sectarian version — more like the Taliban.

For all of these reasons, an opposition victory could mean trading one regime of persecution and slaughter for another. All of this needs to be factored into any U.S. discussion of whether to help the rebels prevail.

If Washington does choose to intervene, however, there are ways to reduce these risks. First, America could start providing lethal assistance, particularly more advanced anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons to help kill off the regime’s heavy weapons faster and allow the opposition to prevail more quickly.

Even more important, the United States and its NATO allies could begin to provide military training for Syrian fighters. More competent opposition forces could better meet and defeat government troops. Such training would also help diminish the factionalism among the armed groups and bring greater discipline to the opposition, including in a postwar environment. Indeed, the American program to organize and train a Croatian (and Bosnian Muslim) army in the mid-1990s was crucial both to military victory in the Bosnian civil war and to fostering stability after the fighting.

Moreover, one of the best ways for the United States to influence a post-civil-war political process is to maximize its role in building the military that wins the war.

Ending a war vs. building a nation

Historically, the only real alternative to ending a civil war by picking a winner is for an outside force to suppress the warring groups and then build a stable political process that keeps the war from resuming. The military piece of this — shutting down the fighting — is relatively easy, as long as the intervening nation is willing to bring enough force and use the right tactics. The hard part is having the patience to build a new, functional political system. The Syrians in Lebanon, NATO in Bosnia, the Australians in East Timor and the Americans in Iraq demonstrate the possibilities and the pitfalls.

This course is typically the only way to end the violence without the mass slaughter of the losing side. It also can prevent fragmentation and an outbreak of fighting among the victors. If done right, it can even pave the way toward real democracy (as the United States started to do in Iraq before its withdrawal last year), which results in greater stability in the long run.

But it is not cheap, and it requires a long-term commitment of military force and political and economic assistance. The cost can be mitigated in a multilateral intervention such as in Bosnia and Kosovo, rather than a largely unilateral effort along the lines of the U.S. reconstructions of Iraq and Afghanistan. In the case of Syria, that means the United States isn’t the only nation that needs to sign on; Turkish, European and Arab support matter as well.

Right now, there is absolutely no appetite in the United States for a Bosnia-style intervention in Syria. That is understandable. Unlike in Libya, the humanitarian disasters unfolding in Syria have not been enough to galvanize the United States to action. In addition, there is nothing intrinsically important there for U.S. vital interests. Syria does not have significant oil reserves, nor is it a major trading partner. It is not an ally and was never a democracy. If Syria were merely to self-immolate, it would be a tragedy for the Syrian people but extraneous to American interests.

However, if Syria’s civil war spills over into the rest of the Middle East, U.S. interests would be threatened. Civil wars often spread — through the flow of refugees, the spread of terrorism, the radicalization of neighboring populations, and the intervention and opportunism of neighboring powers — and Syria has all the hallmarks of a particularly bad case.

At its worst, spillover from a civil war in one country can cause a civil war in another or can metastasize into a regional war. Sectarian violence is already spreading from Syria; Iraq, Lebanon and Jordan are all fragile states susceptible to civil war, even without the risk of contagion. Turkey and Iran are mucking around in Syria, supporting different sides and demanding that others stop doing the same. Terrorism or increasing Iranian influence might pull even a reluctant Israel into the fray — just as terrorism and increasing Syrian dominance pulled Israel into the Lebanese civil war years ago.

This is what we must watch for. Spillover may force Washington to contemplate real solutions to the Syrian conflict, rather than indulge in frivolous sideshows. If that day comes, our choice will almost certainly be between picking a winner and leading a multilateral intervention.

Chances are we will start with the former, and if that fails to produce results, we will shift to the latter. That may seem far-fetched, but it is worth remembering that in 1991 there was virtually no one in the United States who supported an American-led multilateral intervention in Bosnia, and by 1995 the United States (under a Democratic administration) was doing just that.

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: The Washington Post

Image Source: Goran Tomasevic / Reuters

August 7, 2012

Unraveling the Syria Mess

[image error]The Saban Center for Middle East Policy joined with the American Enterprise Institute and the Institute for the Study of War in June 2012 to host a one-day crisis simulation that explored the implications of spillover from the ongoing violence in Syria. The simulation examined how the United States and its allies might address worsening instability in Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey, and elsewhere in the Middle East as a result of the internecine conflict in Syria.

The Saban Center’s Middle East Memo, “Unraveling the Syria Mess: A Crisis Simulation of Spillover from the Syrian Civil War,” authored by simulation conveners Kenneth M. Pollack, Frederick W. Kagan, Kimberly Kagan, and Marisa C. Sullivan, presents key lessons and observations from the exercise.

Among the key findings:

A humanitarian crisis alone is unlikely to spur the international community to take action in Syria.

Turkey is a linchpin in any effort to end the fighting in Syria, but Washington and Ankara may not see eye-to-eye on what the end game should be.

U.S. history in Iraq and Lebanon make intervention there unlikely, even if spillover causes a renewal of large-scale violence.

The simulation suggested a tension between U.S. political antipathy toward greater involvement in Syria and the potential strategic desirability of early action.

Download Media

Unraveling the Syria Mess

Downloads

Download the paper

Video

Unraveling the Syria Mess

Authors

Kenneth M. PollackFrederick W. KaganKimberly KaganMarisa C. Sullivan

Image Source: © Stringer . / Reuters

August 6, 2012

Unraveling the Syria Mess

In June 2012, the Saban Center for Middle East Policy joined with the American Enterprise Institute and the Institute for the Study of War to host a one-day crisis simulation that explored the implications of spillover from the ongoing violence in Syria. Senior Fellow Kenneth Pollack identifies the simulation's lessons for effective intervention in Syria, including the central importance of Turkey in the region.

Video

Unraveling the Syria Mess

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

July 18, 2012

The Deteriorating Situation in Syria: A Discussion Among Four Brookings Middle East Experts

Editor's Note: Following the bombing that killed Syria’s Defense Minister and Deputy Defense Minister, British Foreign Secretary William Hague described the situation in Syria as "deteriorating rapidly," while Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel called on the United Nations to take “urgent” action and pass a new resolution on Syria. Brookings Middle East experts Michael Doran , Kenneth Pollack , Daniel Byman , and Salman Shaikh discuss the current developments in Syria and the implications for the United States.

Michael Doran: Today’s events in Syria are game changing. Bashar Assad might have to dump Damascus, because it lies outside the Alawite enclave. Take a look at this Washington Post article: http://t.co/lKqtR45p. Reacting to it, Michael Young (@BeirutCalling), tweeted the following question: “Will Assad's reserve elite units defend Damascus if all is near lost, or will they redeploy to defend Alawi heartland?” That is a great question. My theory is that, in fact, they will redeploy, and the elite security services will eventually become an Alawite militia, a Syrian form of Hezbollah, with or without Assad. At any rate, the battle for Damascus may give us some insight into future trends. All of this, of course, raises the question: what is Iran's Plan B? (The U.S. does not yet have a Plan A, so it is not worth asking what the Plan B is.)

Kenneth Pollack: I share Michael's perspective. Holding Damascus might prove too much for the rump Syrian Armed Forces--increasingly just an Alawite militia, like the Lebanese Armed Forces became during the 1970s-1980s. The obvious move for them is to hunker down in the mountains around Latakiya and defend the Alawi heartland. But, as we are seeing, they won't give up Damascus without a fight and their residual heavy weapons could make that a very long one. As I’ve said in the past, they might eventually end up as a Syrian version of the Northern Alliance, holed up in the Panjshir valley.

Daniel Byman: A question to me is whether the violence will spike dramatically -- far more than it has already. We have both desperation (defense of Damascus) and revenge (death of a very prominent figure) that could lead to the units being moved from the Golan to use their firepower and simply level rebellious neighborhoods rather than cordon them off.

My understanding is that Damascus is a very diverse city. Clearly, many regime supporters are in the capital. But there are also poorer neighborhoods, outskirts of the capital, etc. that house many Sunnis that are very hostile to the regime. And as the violence rises in the city, we will see “cleansing” of neighborhoods by partisans of each side. So there are, and may be more, areas in Damascus where the regime can (if it chooses) employ heavy force in a demonstrative way.

Salman Shaikh: I don't think the Alawi minority will stand with the regime to the end. At this stage, they cannot guarantee that there will be a "safe haven" in the mountains for the family. The environment around Latakia is increasingly hot with rebel penetration. There are also some indications of Alawis getting more and more nervous about this family's ability to save them.

Today's event means that we are on the road to the end of this regime. The one person whose name I have not seen is Mohamed Nasif - the "godfather" of the security apparatus. If he had gone, then really we would be talking about "game over". Makhlouf was probably the number two of the security apparatus.

Together, they are the "two legs" of Bashar Assad (the closest to him). I have been in Cairo with quite a few of the folks involved in the operations in Damascus, Aleppo etc. They are working feverishly (one predicted “a big event” would happen today last night over dinner). We may still be headed for a big, drawn out bloody battle (especially since the rebels are still poorly equipped; though there has been a relatively large infusion of arms courtesy of Q/KSA via Turkey over the past week), but other scenarios of a quick regime collapse cannot now be ruled out.

It is therefore imperative that the opposition accelerate its readiness of to lead the transitional phase. They would need to form an as yet elusive coordination committee, involving the main opposition blocs (including Kurds and some folks from the inside) and get that committee to deepen their understandings on arrangements for the transition.

Daniel Byman: I think Salman has the key issue exactly right. The opposition’s ability to lead is what will determine whether this is a “win” for the U.S. (and Syria and its neighbors) in the long-term. And the opposition’s coherence will make it better able to topple Assad.

Kenneth Pollack: Salman, I hope that you are correct, but fear it will prove otherwise. I am afraid I have seen exactly the kinds of cross-signals too many times in the past. On occasion, and eventually they may prove correct (Yemen), but most of the time they are ultimately trumped by the fear of retribution for a failed coup and the sense that internal dissension would ultimately lead to collapse (Lebanon, Afghanistan, Bosnia, Iraq, etc.)

Michael Doran: Another question for you: Whither Aleppo? It's a mystery to me. I have never understood why the regime had such a good grip on it, and why Damascus would explode before it did. If by the end of the week, we have major violence in both cities, then the Alawis will certainly be heading for the hills. But I would like somebody with real knowledge to explain the stability of Aleppo.

Salman Shaikh: Aleppo: Huge number of detentions (thousands); regime economic investments; MB has not wanted Aleppo to explode (their strategy is to be ready for the day after); Turks don't necessarily want Aleppo to explode either (refugees). Also protests have become large recently but are not well covered by Arab media. Regarding Tlass - this is seen as a failed Russian/Iranian play for a "constructive" scenario. They are too late.

Michael Doran: Fascinating re: Aleppo. I'm sticking by my Alawite enclave theory, however. I'm sure the average Alawites dislike Bashar and feel caught between the regime and the Sunnis, but will they really be able to resist when Bashar's loyal divisions settle down in the north with Russian and Iranian backing? It's speculation on top of speculation, I do admit. But I don't know anybody who truly has a clue about intra-Alawite politics, so my speculation is as good as any!

Authors

Michael DoranKenneth M. PollackDaniel L. BymanSalman Shaikh

Image Source: Reuters

Kenneth M. Pollack's Blog

- Kenneth M. Pollack's profile

- 41 followers