Kenneth M. Pollack's Blog, page 2

November 8, 2016

20161108 Al Jazeera Pollack

November 2, 2016

Iraqi Kurdistan: Mosul and beyond

I spent last week in Irbil, Iraq along with Michael Knights of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. We met with a wide range of senior Iraqi and Kurdish officials, as well as journalists, analysts, and academics. The trip included a visit to Kirkuk after the terrorist attack there on October 21 as well as time spent near the frontlines, observing Peshmerga military operations against the Islamic State (also known by its Arabic acronym, Da’esh) and discussing the campaign with U.S. and Kurdish military officers.

This post describes my impression of events in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) of Iraq. A prior post described my sense of developments in the liberation of Mosul and Iraqi politics more generally.

The view of Mosul from Irbil

Across the board, the Kurds appear generally pleased with the military aspects of the Mosul offensive.

Author

[image error]

Kenneth M. Pollack

Senior Fellow - Foreign Policy, Center for Middle East Policy

One area of the military campaign that many Kurds point to as a pleasant surprise has been the cooperation they have been receiving from the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and the U.S.-led coalition. This despite the complete absence of American air support for the Peshmerga on October 20, and the failure of the ISF to attack on October 23. Any number of Kurdish leaders, including some of the highest in the land, talked about how after 55 years (or more) of intermittent combat between the Iraqi Army and the Peshmerga, the two forces were getting on extremely well. Not only were they working well together, but soldiers and officers on both sides showed respect toward one another and an easy camaraderie that bemused—and encouraged—their leaders.

Meanwhile, the Kurds indicated a consensus that they had no desire to go into Mosul itself. That sentiment held among many senior Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) personnel as well, who have the most to gain from taking the Kurdish sections of Mosul, which are pro-KDP and therefore potentially important voters.

Almost across the board, Kurdish leaders evinced a philosophical wait-and-see attitude to post-liberation Mosul. They adamantly believed it was a mistake not to have had an agreed-upon plan among all of the potential participants, and they fear that the Iraqi government will not be up to the challenge of handling it itself. However, they showed no inclination to get involved. Indeed, several very senior Kurdish leaders stated matter-of-factly that if the stabilization of Mosul fails and there is widespread fighting, they plan to do no more than defend their own lines, bring in refugees and leave the mess to the Iraqis and Americans to clean up. We heard no apocalyptic threats that widespread fighting in Mosul would inevitably trigger Kurdish intervention, which was noteworthy.

To the extent that the Kurds are concerned about the military campaign to defeat Da’esh, their fears dwell on events farther west, at Sinjar and Tal Afar. In both places, minority populations—Yazidis and Turkmen respectively—create sources of potential conflict. The Yazidis of Sinjar are caught between the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK (and behind them, the Patriotic Union, or PUK, and Iran) on one side, and the KDP and Turkey on the other. For their part, the Turkmen of Tal Afar are divided between Sunnis who furnished many recruits and top leaders for Da’esh but are also “protected” by Turkey, and Shiites who were badly oppressed by the Sunnis and Da’esh. Not surprisingly, the Shiite Hashd ash-Shaabi (Popular Mobilization Forces) have vowed to liberate their Shiite (Turkmen) brethren and punish the Sunnis for their embrace of Da’esh. The Kurds, particularly the Turkish-aligned KDP, echo Ankara’s warnings that a PKK move on Sinjar or a Hashd ash-Shaabi move on Tal Afar could unleash a Turkish invasion. That, in turn, could draw in KDP intervention on the Turkish side, and PUK intervention on the PKK-Iranian side. That would be disastrous, and even if the PUK and KDP avoided open combat, it would further poison their strained relations.

Members of the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS), a militia affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), stand in the village of Umm al-Dhiban, northern Iraq, April 29, 2016. REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic.

Members of the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS), a militia affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), stand in the village of Umm al-Dhiban, northern Iraq, April 29, 2016. REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic.Persistent political stalemate

In part because of the uncertainty surrounding future developments at Sinjar and Tal Afar—and in part because the KRG has little bandwidth beyond that which is focused on Mosul—the domestic political scene remains frozen in Irbil. Of course, there are other reasons as well. The PUK remains locked in the ongoing battle for control of the party between the Talabani family and a group of challengers centered around KRG Vice President Khosrat Rasul Ali and former KRG Prime Minister Barham Salih. Meanwhile, the Gorran party—the second largest in the KRG parliament—is itself paralyzed by its mishandling of the 2015 protest moves against the KDP and the fact that its own outsized leader, Nawshirwan Mustafa, has been on extended medical leave abroad for chemotherapy. Most Kurds believe that Nawshirwan’s condition is terminal and Gorran seems in disarray, unable to do anything in his absence and unable to pick a new leader, even a temporary one.

There is a growing recognition across the Kurdish leadership that the current deadlock is an embarrassment and a failure on all of their parts. Unfortunately, both the PUK and Gorran seem too preoccupied with their own internal crises to do anything about it. Because governance lies primarily with the KDP at present, they are the ones most caught up in the Mosul fight and can afford to concentrate on it by arguing (not necessarily incorrectly) that neither Gorran nor the PUK is unified enough to hold meaningful negotiations. Still, senior KDP leaders claim that they plan to make dramatic—and constructive—moves after the liberation of Mosul to try to form a new government and get things moving again. Surprisingly, they are also adamant that there will be new elections in 2017. These could help or hurt depending both on the distribution of seats in the parliament and the ability of the PUK and Gorran to respond positively to any serious KDP effort to overcome their differences, assuming that there is one.

Progress toward independence…

Two factors that appear to be major contributors to the strangely positive feel to Irbil despite the problems swirling around it, are the progress the Kurds feel they have made on both independence and internal reform. In the past month, senior Kurdish officials including KRG President Mas’ud Barzani and Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani have had what they characterize as positive and constructive conversations with Shiite political leaders in Baghdad, including Prime Minister Abadi, regarding Kurdish independence. They say that Abadi and other moderate Shiite leaders were receptive to the KRG’s desire for independence—or at least full sovereignty within a confederal structure. The two sides have agreed to establish a joint committee to discuss a peaceful secession process, which Kurdish moderates have been seeking for years, in part as a way to forestall a precipitous move toward independence by more hardline Kurdish leaders.

Related

[image error]

Markaz

Everyone says the Libya intervention was a failure. They’re wrong.

Shadi Hamid

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

[image error]

Markaz

What Americans really think about Muslims and Islam

Shibley Telhami

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

[image error]

Markaz

Between Iraq and a hard place: How the battle in Mosul will affect ISIS control in the region

Ranj Alaaldin and Sumaya Attia

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

Barzani is no fool and understands that Abadi may well be driven by his immediate need for KDP support against Maliki, as I described in my previous post. Nevertheless, the Kurds do believe that Abadi is sincere in his willingness to allow the KRG to secede, and Abadi has expressed this sentiment to many others, including myself as recently as March 2016. Moreover, the Kurds have insisted that a decision to secede cannot be agreed to by Abadi alone; they have demanded that the entire Iraqi National Alliance (the Shiite umbrella group) bless any deal for independence. When pressed about Abadi’s ability to deliver on this critical question, and on the likelihood that the deal would survive if Abadi loses Iraq’s 2018 parliamentary election to former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki or Hashd ash-Shaabi leader Hadi al-Ameri, the Kurds acknowledged the risk. However, they also indicated that they believe this to be a reasonable way forward for them, one that they are determined to explore even if it leads nowhere.

Consequently, I found an important shift in Kurdish thinking about independence. The Kurds once believed that the road to independence ran through Ankara, but they now believe it runs through Baghdad. Most Kurdish leaders, at least KDP officials, continue to believe that they can convince Ankara to support an eventual, peaceful secession. However, they acknowledge that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s new problems with the Turkish and Syrian Kurdish populations—perhaps coupled with his increasingly volatile behavior—has made him a less reliable ally in this matter.

The Kurds once believed that the road to independence ran through Ankara, but they now believe it runs through Baghdad.

As part of their efforts in this area and another sign of tangible progress, the Kurds have been in discussions with the Central Bank of Iraq to open a branch in Irbil. This would finally give the KRG some ability to control local financial circumstances, and possibly pave the way toward a more expansive monetary policy under independence or confederation.

Indeed, another debate that the Kurds only seem to be tentatively approaching is the potential question of independence or confederation? Because discussions with Baghdad are still in their infancy, and much will depend on the KRG’s security and economic circumstances at the time that these negotiations reach maturity (if they ever do), it is impossible to know what the Kurds will decide. Still, the more moderate KRG leaders appear to believe that confederation could represent an acceptable interim status, with the expectation that this would eventually translate into full independence somewhere farther down the road. In particular, they stress that if the KRG can gain full sovereignty, full control of their defense policy (including the right to buy military hardware directly and receive end-user certificates), full control of their energy policy (including the right to sell oil on their own, and so eliminate the discount that they are forced to pay because of the uncertain legality of their current oil exports), and full control over monetary policy (including the right to print money, establish their own central bank, issue public debt and borrow from international financial institutions and other foreign lenders), they will be content with confederation.

…And progress on reform

Meanwhile, Kurdistan’s undervalued reform agenda continues to move along smartly, marking milestones that are quite remarkable in their own right. The KRG has completed a comprehensive external audit of the finance ministry and has engaged a former finance minister of Lebanon (highly-regarded for fighting corruption there) to overhaul the finance ministry in Irbil. The KRG has retained both Ernst & Young and Deloitte, to conduct a massive audit of the entire oil and gas sector—something that will now be done on an annual basis to root out corruption and inefficiency in that critical sector. In the past year, Irbil has reduced subsidies and cut government salaries by 49 percent, all part of an austerity program more severe than any other in recent years. The economist Athanasios Manis has calculated that KRG fiscal consolidation equaled 37 percent of GDP during the past three years. He notes that Greece, whose austerity program has famously pushed the country to the brink of revolution, only implemented a fiscal consolidation of 16.7 percent and that was over five years. Yet there has been no public backlash against these measures except for a strike by policemen who wanted to be classified as security personnel and so exempted from the salary cuts.

Related Books

[image error]

Upcoming

Iran Reconsidered

By Suzanne Maloney

2017

T

Upcoming

Turkey and the West

By Kemal Kirişci

2017

[image error]

Upcoming

Escaping the Escape

Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung

2017

The next two programs of KRG reform are aimed at further reducing costs and corruption. The first will target the electricity sector, privatizing distribution, metering (and charging for) consumption, and improving the distribution infrastructure to reduce “leakage” from the age and poor quality of much of the grid. The second will introduce a biometric registration program (including fingerprints and iris scans) for all KRG civil servants, including the Peshmerga. Only those registered in the biometric database will be able to collect paychecks, potentially eliminating tens or even hundreds of thousands of ghost workers and soldiers. This new program will begin in November and should be complete by January. Moreover, Irbil intends to marry the biometric database to an electronic payment system to ensure that salaries are paid automatically and expeditiously, and to further minimize the ability of thieves to collect unearned salaries.

These reforms are remarkable and little appreciated by the Kurdish public, which (understandably) focuses only on their unpaid salaries and the reduction in government services required by the austerity program.

Many Kurds still hope that independence will solve their problems in the short term, by allowing the KRG to borrow money both domestically and internationally, by eliminating the discount on KRG oil exports, and by giving them full control over their monetary policy. The fact that they now feel like there is real hope for a peaceful secession has been a significant psychological boon. However, over time, it is likely that if these far-reaching reforms in economics and governance continue and expand, they will ultimately be the greatest benefit to Kurdistan, potentially setting it on the course to eventual stability, if not real prosperity.

Get daily updates from Brookings

Enter Email

November 1, 2016

Iraq in the eye of the storm

I spent last week in Irbil, Iraq along with Michael Knights of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. We met with a wide range of senior Iraqi and Kurdish officials, as well as journalists, analysts, and academics. The trip included a visit to Kirkuk after the terrorist attack there on October 21 as well as time spent near the frontlines, observing Peshmerga military operations against the Islamic State (also known by its Arabic acronym, Da’esh) and discussing the campaign with U.S. and Kurdish military officers.

This post describes my impression of events in Iraq, including political developments in Baghdad. A second post will describe my sense of developments in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Hard fighting, but on track

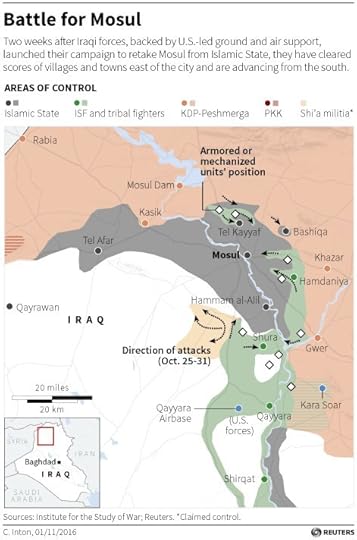

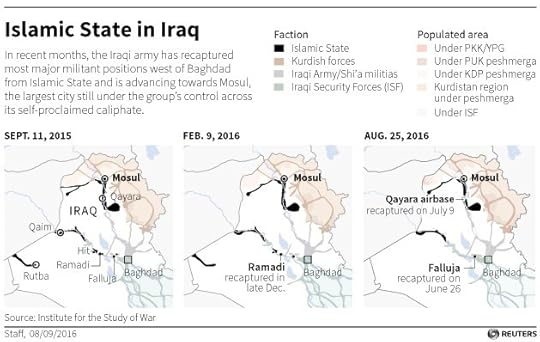

Militarily, the battle for Mosul appears to be going largely according to plan, so far. Coalition forces continue to push forward, tightening the noose around the city from multiple axes of advance. One of the big surprises was that Peshmerga and Iraqi army units have been cooperating remarkably well. Iraqi formations have conducted passages of lines through Peshmerga formations, and armor from the Iraqi Army 9th Mechanized Division has been supporting Kurdish attacks south of Irbil.

Author

[image error]

Kenneth M. Pollack

Senior Fellow - Foreign Policy, Center for Middle East Policy

Da’esh forces are fighting back very hard and giving ground only reluctantly. In many cases, the Iraqis and Kurds have preferred to surround and besiege Da’esh-held towns rather than take the heavy casualties they would likely incur clearing them. It is worth noting that the evidence and analysis seems mixed as to whether Da’esh is withdrawing forces from Mosul to conserve them for the defense of Raqqa, or pushing reinforcements into Mosul to bleed the coalition and postpone (or even prevent) a coalition offensive against Raqqa.

Nevertheless, Da’esh has not been able to defeat or derail the offensive. Although it is impossible to know Da’esh intentions for certain, it seems most likely that the attack on Kirkuk on October 21 was a long-planned counterattack. Da’esh is famous for attempting horizontal retaliation—attacking somewhere else to compensate for a loss, like its assault on Ramadi after the coalition took Tikrit in 2015. The Kirkuk attack falls into that pattern. In addition, the attack was a complex one, involving agents that had been infiltrated into the city at least days, and probably weeks or months, beforehand coupled with a larger infiltration of fighters after the Mosul operation had started. While the attack was frightening, it was swiftly defeated and had no impact on the operation.

That said, there have been problems. For instance, on October 23, the Iraqi Army and Kurdish Peshmerga were meant to launch simultaneous attacks on Da’esh from supporting axes of advance, but the Iraqi army simply did not attack at all. It is unclear why, but they returned to the fight with brio the next day, possibly to make up to the Kurds for their prior day’s failure.

Of potentially greater significance, there are indications that the United States has too little air power in the region to meet all of its support requirements. On October 20, the United States did not provide any air support to Kurdish forces. Senior Kurdish officials were absolutely livid about this lapse. It is unclear why, but American personnel in the field complain that there simply are not enough airframes available. That may be particularly acute at present with Kurdish and Iraqi army forces advancing along at least five axes of attack. Because Kurdish and Iraqi forces have become dangerously dependent on American air strikes to advance, coalition air power appears to be pulled in too many directions to support too many operations, leaving too little for many sectors and none at all for some.

Nevertheless, there is every indication that the coalition forces will continue to advance and should be in jump-off positions for the assault on Tikrit itself in the next few weeks, with the attack on the city proper likely to commence soon thereafter.

A member of Peshmerga forces looks through a pair of binoculars on the outskirts of Bashiqa, east of Mosul, during an operation to attack Islamic State militants in Mosul, Iraq, October 30, 2016. REUTERS/Azad Lashkari.

A member of Peshmerga forces looks through a pair of binoculars on the outskirts of Bashiqa, east of Mosul, during an operation to attack Islamic State militants in Mosul, Iraq, October 30, 2016. REUTERS/Azad Lashkari.Post-liberation plans remain mysterious

One of the more surprising, and depressing, aspects of the operation has been how little is known about any post-liberation plans for securing, governing, and rebuilding Mosul. None of the Kurdish parties, none of the other Iraqi groups slated to participate in the operation, not the Turks, nor the Shiite Hashd ash-Shaabi (Popular Mobilization Forces) are aware of any specific plans for this. They all insist that they have only been briefed in the most general terms and have not been asked to sign onto any detailed plans. The Kurds have agreed to keep their Peshmerga several kilometers back from the city and to leave the assault itself to the Iraqi security forces (ISF). The leaders of other groups who will participate in the operation have been given sectors to assault and guidance about what others will do to take the city, but nothing about what happens when the city is taken.

Of course, the U.S. government is not manned by complete idiots. American officials are well aware of the potential for problems in Mosul and therefore of the need for some kind of plan for how to handle the situation. Indeed, numerous reports indicate that while the United States may have started late, it has spent time and energy discussing this issue, including in conversations with its Iraqi and coalition partners. So I think it a mistake to assume that the Obama administration is simply ignoring this problem.

Related

[image error]

Markaz

Everyone says the Libya intervention was a failure. They’re wrong.

Shadi Hamid

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

[image error]

Markaz

What Americans really think about Muslims and Islam

Shibley Telhami

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

[image error]

Campaigns & Elections

What the 2016 U.S. presidential election means for the Middle East

John Hudak

Monday, February 22, 2016

Instead, all of this strongly suggests that the United States has decided to allow the Iraqi government to take the lead on post-liberation Mosul and handle the situation however it sees fit. The United States would then simply keep all of the other Iraqi and regional actors either out of the attack or out of the business of running Mosul once Da’esh has been defeated there.

If this is the course of action that the United States has chosen to adopt, it has certain advantages. It is, obviously, the simplest solution for the United States to yet another thorny Iraq problem. It obviates the need for complex planning and complicated deal-making among the different groups intent on staking their claim to part or all of Mosul. It has the advantage of being legally sound, since the government of Iraq has sovereignty over the city. It is unquestionably what Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi wants, and since he and the Iraqi government are America’s primary allies, conforming to his preferences makes it unlikely that the will take actions to deliberately complicate the operation. Finally, it obviates the need for painful and time-consuming negotiations among a welter of competing groups that could have pushed off the start of the offensive for weeks or months. That would make it nearly impossible to liberate Mosul before President Obama leaves office, which may also have been an important political consideration for a president who campaigned on a platform of ending the Iraq war at all costs.

However, leaving post-Da’esh Mosul entirely in the hands of Baghdad and simply following its lead also entails considerable risks. The government of Iraq has shown only a very modest capacity to conduct such operations. At Tikrit, Ramadi, and Fallujah, the Iraqi government can claim a number of important achievements, but these were much smaller towns and there were as many problems as there were successes in these operations. The Iraqis have (hopefully) learned and will do better this time, but the scale of this operation—and the need to pursue ongoing operations elsewhere simultaneously—could swamp the capabilities of the central government.

Moreover, pursuing such an approach would also mean rolling the dice regarding various actors beyond the full control of the Iraqi government: the Hashd ash-Shaabi, Atheel al-Nujayfi’s Nineveh Guard, various Sunni tribes, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the Turks. In the absence of an agreed-upon plan that gives all of these actors a well-defined mission and boundaries on their activities (both geographic and operational), they may choose to just grab whatever they can. Indeed, many expect that these groups will try to carve out sectors for themselves regardless of what the Iraqi government or the Americans say, and the danger is that this will turn into a violent free-for-all as different groups try to establish facts on the ground.

The apparent decision to simply follow Abadi’s lead and leave post-liberation Mosul to the Iraqi government raises the question of whether the Obama administration is repeating the same mistake it has in the past. From 2009 to 2014, the administration backed the government of Prime Minister Maliki to a far greater extent than the facts warranted. Throughout that period, U.S. officials endlessly defended his actions in public, and did little in private other than to urge restraint. These warnings typically had the same force as reminders to “please think of the environment before printing” at the bottom of emails.

The result was disastrous. Without any American pressure to change his behavior, Maliki subverted Iraq’s democracy, alienated the Sunni community, destroyed the Iraqi military, enabled the Da’esh conquest of northern Iraq, and drove the country back into civil war. Throughout, the Obama administration insisted that it was right and ignored warnings from a vast range of Iraqis, regional allies, coalition partners, and experts on Iraq. There is a disturbing sense that history may be repeating itself. While Abadi is a far cry from Maliki, with the best of intentions and some willingness to act on them, he has made mistakes and has a limited capacity to govern. At the most basic level, getting the stabilization and reconstruction of Mosul right is likely to be an enormously complex undertaking and any Iraqi government could doubtless benefit from external advice, assistance, and guidance—especially from the United States, the former occupying power who has done this many times in the past, both correctly and incorrectly. The mistakes made with Maliki should make clear the dangers of the United States uncritically backing an Iraqi prime minister who follows his own beliefs rather than what the historical record demonstrates is best warranted, no matter how much we may like him.

U.S. President Barack Obama (R) meets with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi during the Group of Seven (G7) Summit in the Bavarian town of Kruen, Germany June 8, 2015. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque.

U.S. President Barack Obama (R) meets with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi during the Group of Seven (G7) Summit in the Bavarian town of Kruen, Germany June 8, 2015. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque.Crisis averted in Baghdad, but another brewing

Abadi himself appears to have been shaken by the most recent effort to bring down his government, but he also appears to have survived it and seems determined to win big at Mosul to ensure his re-election.

Over the summer, former Prime Minister Maliki engineered the forced resignations of Defense Minister Khaled al-Obeidi and Finance Minister Hoshyar Zebari. He had set his sights on Foreign Minister Ibrahim Jaafari next, and begun to create problems for Speaker of the Parliament Salim al-Jabouri. All expectations were that Maliki hoped to cause the fall of the government and so bring down Abadi, his former aide. Although Maliki may still be able get Jaafari dismissed and has effectively hobbled Jabouri to the point where he dare not oppose Maliki’s political moves, the word from Baghdad is that Abadi’s job is safe. The Obama administration made clear to all who would listen that they would pull their military support if Abadi were removed as prime minister, and that forced Abadi and his allies to back down. (It also demonstrated the revived influence of the United States.)

Related Books

[image error]

Upcoming

Iran Reconsidered

By Suzanne Maloney

2017

T

Upcoming

Turkey and the West

By Kemal Kirişci

2017

[image error]

Upcoming

Escaping the Escape

Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung

2017

At this point, most Baghdad political elites believe that Maliki will continue to pursue these various leaders, but largely out of a desire for revenge: Many of them were key players in his removal from the premiership in 2014. Several Iraqi leaders told us that Maliki is telling people that he regrets having agreed to step down as prime minister in 2014. In contrast, he is also claiming that he does not want to be prime minister again, although he wants to be able to choose the next one. This may be true, but I would note that in 2014, Maliki endlessly told people (including myself) that he did not want to be prime minister again after the 2014 elections, only to fight ferociously to be re-elected.

The current consensus appears to be that Abadi will remain prime minister until the 2018 elections. There is considerable discussion of delaying the 2017 provincial elections until April 2018 to hold them simultaneous with the national/parliamentary elections. This may be to save money, or to prevent Abadi from suffering the same fate as Maliki, who won the 2009 provincial elections only to then lose the 2010 national elections.

Combining the two elections also means that it will be harder to predict ahead of time how various candidates will do in the national elections. In particular, there is tremendous uncertainty about political developments in southern Iraq over the past two years while Iraq’s security forces and the attention of its political leadership have shifted from south to north to deal with Da’esh. It is entirely possible that various parties tied to the worst of the Shiite Hashd ash-Shaabi will win big in southern Iraq.

Consequently, while it is still a very long way to the 2018 elections, especially in Iraqi political terms, the three front runners in the election at present are Prime Minister Abadi, former Prime Minister Maliki, and Hashd ash-Shaabi chief Hadi al-Ameri. What’s more, although Abadi is still the favorite at this time, al-Ameri appears to have a considerably better chance of winning that previously believed likely. Because his militias have gained power and economic influence in southern and eastern Iraq in the absence of the ISF, he could win very big there. Although al-Ameri has close ties to Iran and has presided over many of the Hashd ash-Shaabi’s worst activities, he is pragmatic and has shown a willingness to work with the United States, such that Washington may not try to block him if he won the election.

Meanwhile, although Abadi has survived Maliki’s bid to unseat him, he remains hamstrung in Baghdad. He has little ability to push legislation through the Maliki-controlled parliament, his inner circle is too small to effectively run the sclerotic Iraqi bureaucracy, and most of his former political allies have deserted him. In short, he needs help.

He got two boosts earlier this month. The first came in in the revival of the pan-Shiite Iraqi National Alliance and their decision to name Ammar al-Hakim of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq as its head. Ammar was infuriated by Abadi’s failure to consult with him before making several precipitous moves that would have affected ISCI’s standing and patronage—particularly Abadi’s attempt to dismiss his cabinet and name a new technocracy instead. However, Ammar remains a moderate, wary of both Maliki and the more extreme Hashd ash-Shaabi leaders, particularly Moqtada al-Sadr and Hadi al-Ameri, who abandoned ISCI to turn its Badr militia into an independent party of his own. This makes Ammar a natural ally of Abadi’s. Second, Mas’ud Barzani and the Kurdistan Democratic Party decided to back Abadi in Baghdad in return for Abadi starting negotiations over eventual Kurdish independence. I will discuss the latter development at greater length in my next blog post.

Iraqi soldiers celebrate as they pose with the Islamic State flag along a street of the town of al-Shura, which was recaptured from Islamic State (IS) on Saturday, south of Mosul, Iraq October 30, 2016. REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra.

Iraqi soldiers celebrate as they pose with the Islamic State flag along a street of the town of al-Shura, which was recaptured from Islamic State (IS) on Saturday, south of Mosul, Iraq October 30, 2016. REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra.Strangely calm and optimistic in the midst of battle

Despite the fact that the climactic battle with Da’esh for control of Mosul has begun and is far from completion, and despite the fact that few actually know American and Iraqi intentions for stabilizing and rebuilding the city after its liberation, Iraq seems strangely calm and optimistic. Observers from the capital report the same. Abadi has survived Maliki’s (and Muqtada al-Sadr’s) various efforts to unseat him. There is confidence that the war against Da’esh will be won and the fighting itself—and the expectation of victory—appears to be distracting many Iraqis from their political and economic problems. But all of it smacks of a false dawn. A great many fear that the liberation of Mosul will devolve into nightmarish infighting among the victors, like the Afghans after the fall of Kabul in 1992.

Moreover, the hope that Abadi will be able to translate victory at Mosul into progress on governance and reform seems overly hopeful, even though we should all hope for it as best we can. Abadi’s political rivals seem determined to contest him for the glory (Hadi al-Ameri) or simply deny him any greater influence in Baghdad (Maliki). Moreover, if the Iraqi government proves unable to handle the situation in post-liberation Mosul and there is largescale violence, let alone ethnic cleansing, far from benefitting from victory at Mosul, Abadi will be tarnished by post-liberation failures. All of this sets up a very uneasy 2017 for Iraq, a situation that can only be exacerbated by the uncertainty around a new American administration whose Iraq policy can barely be discerned, whichever candidate you believe may prevail next Tuesday.

Get daily updates from Brookings

Enter Email

October 20, 2016

20161020 USA Today Pollack

September 29, 2016

Iraq and a policy proposal for the next administration

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump excoriated President Obama for prematurely disengaging from Iraq and so plunging it back into civil war. President Trump will now have the ability, and the responsibility, to avoid repeating Obama’s mistake. However, doing so is going to require treating Iraq as more than just a host for ISIS—let alone a gas station to be robbed—and instead enact policies that will help Iraq to slowly heal the wounds that allowed ISIS to spawn there. That isn’t as hard as it sounds, but it will require the new administration and its principal officials to see Iraq in a very different light.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump excoriated President Obama for prematurely disengaging from Iraq and so plunging it back into civil war. President Trump will now have the ability, and the responsibility, to avoid repeating Obama’s mistake. However, doing so is going to require treating Iraq as more than just a host for ISIS—let alone a gas station to be robbed—and instead enact policies that will help Iraq to slowly heal the wounds that allowed ISIS to spawn there. That isn’t as hard as it sounds, but it will require the new administration and its principal officials to see Iraq in a very different light.

What needs to be understood is that Iraq is caught in a quintessential ethno-sectarian civil war. It is not the case that Iraq is in civil war because ISIS is there; it is instead the case that ISIS is there because Iraq is in civil war, and eliminating the former will mean confronting the latter. Unfortunately, however, American policy toward Iraq has been badly misguided because it has attempted to address one of the symptoms of the civil war—the rise of ISIS—without addressing the dynamics of the civil war itself.

Civil Wars and the Lessons of History

The modern world has a great deal of experience with civil wars, and one of the stark lessons of this history is that civil wars do not lend themselves to half-measures. While it is entirely untrue that external actors cannot end a civil war, as is often claimed, such wars cannot be ended easily. History demonstrates that half-hearted interventions do not quell a civil war: they exacerbate it.

There is essentially only one approach that a well-meaning external actor can take to end someone else’s civil war. Very crudely, the approach requires three steps: (1) changing the military dynamics such that none of the warring parties believes that it can win a military victory, or that it will be slaughtered by one of its rivals if it lays down its arms; (2) forging a power-sharing agreement by which political authority and economic benefits are divided more or less in keeping with demographic realities; and (3) establishing at least one internal or external institution that is capable of ensuring that the first two conditions endure until trust among the communities and strong internal institutions can be rebuilt. There are multiple ways to handle each of these tasks, but any intervening nation that does not pursue this course of action, that does not bring enough resources, or that is not willing to sustain its commitment long enough to succeed will only make the situation worse.

Consequently, the minimalist approach to Iraq that the United States employed under the Obama administration is highly unlikely to secure American interests there over the long term. The military progress has been admirable, but without comparable political progress along the lines required to end a civil war and prevent its recurrence the exertions so far are likely to prove ephemeral. For Iraq, destroying ISIS and then leaving the country to the Iraqis to sort out their own political problems will not do it. The Iraqis are capable of addressing their myriad problems, but only with American assistance. Unless the United States wants to fight yet another war in Iraq in the near future, the incoming administration needs to be willing to deepen America’s role there.

The Big Picture of a New Iraq Policy

One of the big dangers in Iraq for the new administration is overcoming the false sense of security that ISIS is now effectively defeated and therefore there is nothing more to worry about in Iraq. While the military campaign to evict and eradicate ISIS in Iraq and Syria seems well in train, it cannot be the end of America’s involvement. If Washington repeats the same mistake it committed in both 2003 and again in 2011 by ignoring the political requirements to translate a successful military campaign into an enduring foreign policy achievement, none of the gains are likely to prove lasting. Iraq is likely to fall apart all over again, and President Trump will then face the same frustrating choice of paying the costs to stabilize Iraq yet again or running the potentially catastrophic risks of trying to walk away as both of his predecessors did.

Indeed, if the final eviction of ISIS is not handled properly, it could simply create the circumstances for more widespread conflict. Right now, fear and hatred of ISIS is perhaps the only thing that all Iraqis have in common. The danger is that if it is removed without establishing a process of national reconciliation—or better still, an actual accord—that gives Iraqis faith that their polity remains viable, the civil war will reignite and will shift from a fight of all against ISIS to a fight of all against all.

Iraq’s first great problem now is that its communities have once again lost their trust in one another. Trust is always the first casualty of civil war, and Iraq had only started to rebuild it in 2007–9 before the American withdrawal allowed Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to pursue a sectarian agenda and strip Sunni trust of the Shi’a all over again. After the fall of Mosul, rebuilding that trust must be a top priority. In part for that reason, Iraq will almost certainly need to transition eventually to a combination of federalism and either confederation with the Kurds or independence for an Iraqi Kurdish state.

With regard to the latter, the Kurds constitute a separate nation, and they have made clear for the past century that they do not want to be a part of Arab Iraq. Their forced inclusion in the Iraqi state has resulted in nothing but conflict and misery for both the Kurds and the Arabs. Iraq and the Kurds would both be better off with an amicable divorce, but ensuring its amicability will take time, goodwill, and constructive diplomacy that seem in short supply right now. The United States has important interests in seeing this separation happen peacefully, but little else. The ways in which the Kurds and Arabs will choose to handle territorial issues (including the status of Mosul and Kirkuk), the distribution of oilfields, and the return of displaced persons are not issues on which the United States needs to take a position, but it will be critical that Washington serve as honest broker in helping the parties find solutions that both can accept. It may also be necessary for the United States to help each side make painful concessions, in part by providing bilateral or multilateral aid as compensation. Allowing the Kurds to opt out of Iraq would also increase the demographic and therefore electoral weight of Iraq’s Shi’a Arab community, which will make it all the more important for the United States to help Arab Iraq devise a more stable, equitable, and self-regulating political system of its own.

Recommendations

[image error]

Markaz

Racing to the finish line, ignoring the cliff: The challenges after Mosul

Ian A. Merritt and Kenneth M. Pollack

Monday, September 19, 2016

[image error]

Markaz

Iraq Situation Report, Part I: The military campaign against ISIS

Kenneth M. Pollack

Monday, March 28, 2016

[image error]

Markaz

Iraq Situation Report, Part II: Political and economic developments

Kenneth M. Pollack

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

For this reason, and because the opposite approach had failed miserably by 2014, paving the way for ISIS, Arab Iraq will have to develop a federal structure (as envisioned in the current Iraqi constitution) that delegates greater authority and autonomy to its various ethnic, sectarian, and geographic components. The traumatic experiences of three-and-a-half decades of Saddam Hussein’s tyranny, two bouts of civil war, and Maliki’s brutal attempt to consolidate power in between, have made it inconceivable that Iraq’s communities will accept a return to an all-powerful, highly centralized Iraqi state.

However, in fittingly ironic fashion, the goal of a more decentralized, federal political system now requires a dedicated effort to strengthen Iraq’s central government. The problem is best understood this way: Decentralization can take two forms, empowerment or entropy. Obviously, the former is a positive form that can produce a functional state; the latter a disaster likely to produce war and misery. Decentralization via empowerment requires a reasonably strong and functional central government that grants specific authorities and the power to execute those tasks to subordinate and/or peripheral entities. Decentralization via entropy, in contrast, occurs when the central government lacks the strength to control its constituent parts—let alone to empower them—and so subordinates, peripheral entities, and actors outside the system altogether simply grab authority and resources and do with them whatever they like. Not only does such anarchy invariably dissolve into chaos and conflict, but the actors arrogating power to themselves also are rarely as strong as they would be if their power was delegated by an effective central government. One example of the distinction is the United States created by the Articles of Confederation compared to the United States created by the U.S. Constitution. Under the former, the central government was too weak and so the federal structure did not work, even though the states were far more powerful than they were under the Constitution. The result was anarchy, chaos, and internal conflict. The Constitution provided for a stronger central government, which paradoxically made a stable federal system—with still strong states—both possible and practical.

Unfortunately, what is happening in Iraq today is largely decentralization by entropy, not empowerment and…that is likely to produce renewed conflict in the future.

Unfortunately, what is happening in Iraq today is largely decentralization by entropy, not empowerment, and this is the second, related factor that is likely to produce renewed conflict in the future. It is this entropic pull that is causing the fragmentation that is now the leitmotif of Iraqi politics. The Sunnis have long suffered from a badly atomized leadership, but even that has worsened in recent years, exacerbated by Maliki’s brilliance in targeting any moderate, capable, and charismatic Sunni leader who might have unified that community. But now the Kurds, whose leadership once consisted of Mas’ud Barzani (head of the Kurdistan Democratic Party [KDP]) and Jalal Talabani (head of the rival Patriotic Union of Kurdistan [PUK] party) and no one else, are now increasingly beset by divisions. The long-dormant KDP-PUK split has been reopened, to be joined by a split between the KDP and the opposition Gorran (“Change”) movement, and splits within each of these parties as well. Even the Shi’a leadership is fracturing. Iraqis often like to argue that the Marja’iye (the Shi’a religious establishment centered in Najaf) provides the Shi’a with a unified voice, but if that were ever true, it is proving less and less so. Now, dozens of Shi’a figures can claim leadership over important constituencies, including dozens of new militias, many of which operate outside the control of the central government. This centrifugal trajectory simultaneously paralyzes the Iraqi political system and pushes the country toward chaos and renewed conflict.

Specific Steps for Post-ISIS Iraq

In this context, a new American policy that would have a reasonable prospect of helping Iraq to avoid slipping back into civil war once ISIS is defeated will require the United States to pursue a number of interwoven courses of action.

Forge a New National Reconciliation Agreement

There is simply no way around this foundational requirement. Iraqis need a new power-sharing agreement that will allow all of the rival communities, but particularly the Sunni and Shi’a Arabs, to begin cooperating again. Without this, the military successes against ISIS will evaporate. In recent months, both the United States and the government of Iraq have trumpeted local reconciliation efforts as a bottom-up substitute for a top-down process of national reconciliation. While such grass-roots efforts can be very useful, historically they are no substitute for high-level reconciliation. Without the latter, local efforts are typically undone by rivalries among senior leaders and the result, once again, is renewed civil war. Yet the United States has made far too little effort to bring Iraq’s senior leadership together, hiding behind Baghdad’s desire to handle this matter itself and the self-fulfilling prophecy that Iraq’s leaders are too fragmented. The current Iraqi-led “process” has so far achieved nothing. On the other hand, it is worth noting that in 2007–8, Ambassador Ryan Crocker faced a similar problem of fragmented leadership, yet he and his team brokered exactly the kind of informal but effective national reconciliation that Iraq desperately needs once again.

Push Baghdad and Erbil Toward Short- and Long-Term Solutions

As noted above, it would be better for both Arab Iraqis and Iraqi Kurds if Iraqi Kurdistan were a separate country. Unfortunately, getting to that point without large-scale violence will be very difficult. There are borders to be negotiated, populations to be consulted, and foreign powers to be placated (or stonewalled). Moreover, in the near term, Kurdish political, economic, and security needs may require a closer relationship with Baghdad rather than a more distant one. The Obama administration has put considerable effort toward handling these immediate problems and has helped achieve a certain amount of success. However, without the framework of a long-term plan that creates the circumstances for peaceful Kurdish secession (along the lines of the Czechoslovak model), these near-term gains will erode and eventually collapse as they have so regularly in the past.

Help Baghdad Regain the Basic Capacities of Governance

Even the most extreme advocates of federalism in Iraq recognize that the central government will have to retain certain powers and prerogatives because they are responsibilities that only the central government can realistically discharge. This starts with the role of defending Iraq from external attack and helping its governorates and regions defend themselves against major internal security threats. It means helping Baghdad regain its Weberian monopoly on the use of violence, including demobilizing the Hashd ash-Shaabi (the militias created in 2014 after the fall of Mosul) and/or integrating them into the formal Iraqi security forces. Only after such a reform program will the central government be able to delegate part of its security authority to the internal security forces of its governorates and regions. Strengthening the central government would also give Baghdad the ability to conduct basic functions like gathering revenue and spending it on nationwide services such as power generation and distribution, infrastructure improvements, and economic development—functions that everyone accepts Baghdad will have to retain. That, in turn, requires both wider political reform to ensure a more functional central government overall and more specific reforms to address Iraq’s paralyzed legislature, its corrupt executive branch, and its politicized judiciary.

Strengthen the Abadi Government

The United States can provide Iraq with guidance and some resources to enact the kinds of reforms enumerated above, but most of that work can only be undertaken by the Iraqi government itself. This places a premium on helping the Iraqi government as best we can and far more than we have over the past eight years, which also raises the question of whether the United States should support the current Iraqi government or push for a different one. Although Haider al-Abadi has made mistakes as prime minister, he is still the best we are likely to get. Of greatest importance, he has a number of highly desirable qualities: He is politically courageous, he is not corrupt (as best anyone can tell), he has a clear and correct sense of what Iraq needs to do to escape the civil war trap, and he has shown a willingness and an ability to learn from his mistakes. We could have done a lot worse than Haider al-Abadi. Moreover, replacing him would be more likely to bring to power a worse leader than a better one. Consequently, Washington’s best bet will be to double down on Abadi in the expectation that greater American backing and partnership will enable him to pursue the national reconciliation and political reform that Iraq so desperately needs and that he has repeatedly called for. But that means keeping American skin in the game.

Develop a Robust, Long-Term Aid Program for Iraq

The Obama administration has proven that its early refusal to invest resources in Iraq—and its perverse claim that doing so was senseless because the United States had no influence there—was wrong. Since 2014, the United States has invested considerable resources in Iraq, including 5,000 ground troops, large-scale weapons deliveries, a major air campaign, and significant financial assistance, and as a direct result now has considerably more influence than at any time since 2011. After the fall of Mosul, the United States should maintain this commitment of resources to Iraq. Ideally, the United States would decrease some aspects of its support, like airstrikes and other fire support, and increase other elements to focus more on the political and economic tasks that need to be accomplished after the defeat of ISIS, which arguably are more challenging than the military task of liberating Iraq.

Retain and Rebuild the American Military Presence

Ideally, the United States would keep about five to ten thousand ground troops in Iraq. In terms of missions, these personnel are needed to thoroughly rebuild the Iraqi Security Forces—as the United States finally did in 2007–9—with large numbers of U.S. personnel training, advising, partnering with, and accompanying Iraqi forces down to company level or lower. As part of this, it would be helpful to have American combat battalions, or even brigades, regularly rotate into Iraq to exercise with Iraqi forces. The United States should retain a large special operations counterterrorism force to help Baghdad with the inevitable residual terrorist problem that will persist for some time, even under the best of circumstances, after the fall of Mosul. Further troops would be necessary for force protection, medical support, transportation, communications, and other administrative and security tasks. In addition to carrying out these key missions, the initial size of the force will also be important from a psychological perspective. The Iraqis need to believe that the United States is not abandoning them again, and that the American military presence left behind after the defeat of ISIS is large enough to prevent the country from coming apart at the seams or its government from using force against any of its constituent communities. While even a ten-thousand-man force would have only a very limited prospect of playing that role in practice, history has demonstrated that in postconflict scenarios, the symbolic role is of far greater significance than actual military capability as long as the peacekeeping force is believed to have some degree of capacity and a willingness to employ it.

Establish a Sustained Economic Aid Program

Low oil prices have created dire financial problems for Baghdad, and even more so for Erbil. A World Bank loan of $5.4 billion over three years will help, but it is far from making up Iraq’s shortfall. Additional outside aid can also have an outsized effect in Iraq because Baghdad is so inefficient, corrupt, and bottlenecked that foreign assistance provided directly to those who will spend it comes faster and is of greater utility than trying to squeeze dinars through the Iraqi political process. Moreover, as with a five- to ten-thousand-man military commitment, an economic aid program of (ideally) $1 billion to $2 billion per year for five years would reinforce the impression that the United States is renewing its long-term commitment to Iraq’s stability and development. That symbolism is worth far more than the practical impact of the dollars spent. Moreover, if that money is spent wisely, it can be used to further empower Prime Minister Abadi and other Iraqi leaders looking to move past sectarian differences and break the deadlocks suffocating the Iraqi political system. In this sense, and again coupled with a slightly enlarged long-term American military presence, such an aid program would go a long way to preserving (and perhaps expanding) the hard-won American influence in Iraq to help guide the country down the right path in the years ahead.

Read more in the Brookings Big Ideas for America series »

Iraq: A policy proposal for the next administration

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The principal problem of Iraq, and the principal problem for America with Iraq, are that the country remains caught in an ethno-sectarian civil war. It is that civil war (and the twin conflict in Syria) that has given rise to ISIS, and not the other way around. If the United States is to protect its interests in the Middle East over the long-term, Washington must abandon its single-minded focus on ISIS.

Author

[image error]

Kenneth M. Pollack

Senior Fellow - Foreign Policy, Center for Middle East Policy

That myopic preoccupation has repeatedly caused the United States to take actions that make sense in terms of the narrow defeat of ISIS, but which ultimately exacerbate the civil war, in turn making it more likely that ISIS—or a successor Salafi Jihadist group—will not only survive but further threaten American interests.

It has also limited the American response to other problems stemming from these civil wars such as the refugee problem swamping Europe and the problem of radicalization infecting the Middle East.

After ISIS has been militarily defeated in Iraq and reduced merely to a lingering terrorist problem, the United States needs to be prepared to make a major effort to help Iraq politically.

Security and economic assistance will be a necessary component of this effort because it is by providing security and economic support that the United States will generate the influence it requires to help guide the Iraqi political process.

In particular, the United States needs to focus its efforts on:

Forging a new national reconciliation agreement among Iraq’s senior leaders. While both Washington and Baghdad like to tout their “bottom-up” national reconciliation efforts, historically these have proven inadequate. Without top-level agreement, the bottom-up gets swept away.

Helping to empower the Abadi government. For a variety of hard-nosed reasons, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi remains the United States’ best partner in Iraq. We need to use our influence to help him build up his, and to help him find practical ways to implement his rhetorical commitments to government efficiency, national reconciliation, security sector reform, and the like.

Help Iraq move toward a federal system for the Arab parts of the country and help create a process by which Iraqi Kurdistan can eventually (and peacefully) achieve independence.

Background

Iraq, like Syria, is caught in a quintessential ethno-sectarian civil war, although each is at a different stage of conflict. American policy toward both has been badly misguided because it has attempted to address one of the symptoms of these civil wars—the rise of ISIS—without addressing the dynamics of the civil wars themselves. American strategy in Syria seeks cooperation with the Russians and encourages further conquests by the Kurds because this makes sense in fighting ISIS, but it simply feeds the flames of the civil war. America’s approach to Iraq has been slightly better, but is also overly focused on ISIS at the expense of Iraq’s long-term stability. That’s particularly problematic since the long-term eradication of the Salafi Jihadist threat from Iraq (of which ISIS is merely the latest manifestation) is wholly dependent on Iraq’s long-term stability. Thus, the military progress that the United States has made against ISIS, while very considerable on its own terms, is likely to prove ephemeral without a dramatic shift in the American approach to tackle the civil wars themselves.

The military progress that the United States has made against ISIS…is likely to prove ephemeral without a dramatic shift in the American approach to tackle the civil wars themselves.

The modern world has a great deal of experience with civil wars and one of the stark lessons of this history is that civil wars do not lend themselves to half-measures. While it is entirely untrue that external actors cannot end a civil war, as is commonly claimed, they cannot be ended easily. The history of these civil wars demonstrates that limited interventions do not quell a civil war, they exacerbate it.1

There is essentially only one approach that a well-meaning external actor can take to end somebody else’s civil war. Very crudely, that requires three steps:

changing the military dynamics such that none of the warring parties believes it can win a military victory or that it will be slaughtered by one of its rivals if it lays down its arms;

forging a power-sharing agreement by which political authority and economic benefits are divided more or less in keeping with demographic realities; and

establishing at least one institution (internal or external) capable of ensuring that the first two conditions endure until trust among the communities and strong internal institutions can be rebuilt. There are multiple ways to handle each of these tasks, but any intervening nation that does not pursue this course of action, that does not bring enough resources, and/or that is not willing to sustain its commitment long enough to succeed will only make the situation worse.

Related

[image error]

International Affairs

The regional impact of U.S. policy toward Iraq and Syria

Tamara Cofman Wittes

Thursday, April 30, 2015

[image error]

International Affairs

U.S. policy toward a turbulent Middle East

Kenneth M. Pollack

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

[image error]

Markaz

Iraq Situation Report, Part II: Political and economic developments

Kenneth M. Pollack

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

So far, all of the options being discussed for U.S. policy toward Iraq and Syria fail these tests.2 Either they try to minimize American involvement altogether—as the Obama administration did—and allow American interests to be further undermined by the destabilizing effect of these wars, or they proffer minimal involvement that is highly unlikely to bring an end to either civil war, will almost certainly make them worse, and will waste American resources and further damage American relationships with our regional partners. For Syria, enclaves, no-fly zones, joint operations with the Russians, modest increases in aid to the existing opposition, and the like will not bring about a durable end to the conflict. However, they will enmesh America deeper into Syria and squander American resources. For Iraq, destroying ISIS and then leaving it to the Iraqis to sort out their political problems will not do it either. The Iraqis are capable of addressing their myriad problems, but only with American assistance.

If the United States is going to protect its vital interests in the Middle East, it is going to have to find the courage to end these civil wars before they consume the region, and our interests, altogether. And that means that the next administration must deal with each civil war on its own terms. This essay addresses what that should mean for Iraq.

Get daily updates from Brookings

Enter Email

The big picture of a new Iraq policy

In Iraq, the United States needs to get past a renewed false sense of security. Washington has had considerable success in replacing the problematic Nuri al-Maliki with the progressive Haidar al-Abadi as prime minister, rebuilding elements of the Iraqi security forces, retaking much of the land once conquered by ISIS, securing considerable financial assistance for Iraq, and brokering some important deals to overcome several dangerous political crises. These are all very real achievements and the Obama administration deserves credit for its willingness to commit time, energy and resources to Iraq to effect these changes. But once again, the military campaign now nearing completion cannot be seen as the end of America’s involvement. If Washington repeats that mistake—the same one the United States committed in both 2003 and again in 2011—none of the gains to date are likely to prove lasting. The country is likely to fall apart all over again, and the United States will again face the same frustrating choice of paying the costs to stabilize Iraq (yet again) or running the potentially catastrophic risks of trying to walk away.

In Iraq, the United States needs to get past a renewed false sense of security.

Militarily, Iraq is in the endgame of its conflict against ISIS. The Salafi Jihadist state and its armies will probably be driven from Iraqi territory within the next 6 to 12 months. However, it is not necessarily in the endgame of its civil war. Indeed, if the final eviction of ISIS is not handled properly, it could simply create the circumstances for more widespread conflict. Right now, fear and hatred of ISIS is perhaps the only thing that all Iraqis have in common. The danger is that if it is removed absent a process of national reconciliation (or better still, an actual accord) that gives Iraqis faith that their polity remains viable, the civil war will re-ignite, and will shift from a fight of all against ISIS, to a fight of all against all.

Iraq’s first great problem now is that its communities have—once again—lost their trust in one another. Trust is always the first casualty of civil war, and Iraq had only started to rebuild it in 2007-2009 before the American withdrawal allowed Maliki to pursue a sectarian agenda and strip Sunni trust of Shiites all over again. After the fall of Mosul, rebuilding that trust must be a top priority.

In part for that reason, Iraq will almost certainly need to transition (eventually) to a combination of federalism and either confederation with the Kurds or independence for an Iraqi Kurdish state.

Related Books

[image error]

Get Out the Vote

By Donald P. Green and Alan S. Gerber

2015

[image error]

Why Presidents Fail And How They Can Succeed Again

By Elaine C. Kamarck

2016

[image error]

Billionaires

By Darrell M. West

2014

With regard to the latter, the Kurds constitute a separate nation who have made clear for the past century that they do not want to be a part of Arab Iraq. Their forced inclusion in the Iraqi state has resulted in nothing but conflict and misery for both the Kurds and the Arabs. Iraq and the Kurds would both be better off with an amicable divorce, but ensuring its amicability will take time, goodwill, and constructive diplomacy that seem in short supply right now. The United States has important interests in seeing this separation happen peacefully, but little else. How the Kurds and Arabs will choose to handle territorial issues—including the status of Mosul and Kirkuk—the distribution of oilfields and the return of displaced persons are not issues on which the United States needs to take a position, but it will be critical that Washington serve as honest broker in helping the parties find solutions that both can accept. It may also be necessary for the United States to help each side make painful concessions, in part by providing bilateral or multilateral aid as compensation. Allowing the Kurds to opt out of Iraq would also increase the demographic (and therefore electoral) weight of Iraq’s Shiite Arab community, which will make it all the more important for the United States to help Arab Iraq devise a more stable, equitable and self-regulating political system of its own.

For that reason and because the opposite approach had failed miserably by 2014, paving the way for ISIS, Arab Iraq will have to develop a federal structure (as envisioned in the current Iraqi constitution) that delegates greater authority and autonomy to its various ethnic, sectarian and geographic components. The traumatic experiences of three and a half decades of Saddam Hussein’s tyranny, two bouts of civil war, and Maliki’s brutal attempt to consolidate power in between, have made it inconceivable that Iraq’s communities will accept a return to an all-powerful, highly-centralized Iraq state.3

However, in fittingly ironic fashion, the goal of a more decentralized, federal political system now requires a dedicated effort to strengthen Iraq’s central government. The problem is best understood this way: Decentralization can take two forms, empowerment or entropy. Obviously, the former is a positive that can produce a functional state, the latter a disaster likely to produce war and misery. Decentralization via empowerment requires a reasonably strong and functional central government that grants specific authorities and the power to execute those tasks to subordinate and/or peripheral entities. Decentralization via entropy, in contrast, occurs when the central government lacks the strength to control its constituent parts—let alone to empower them—and so subordinates, peripheral entities, and actors outside the system altogether simply grab authority and resources and do with it whatever they like. Not only does such anarchy invariably dissolve into chaos and conflict, but the actors arrogating power to themselves are rarely as strong as they would be if their power was delegated by an effective central government. One example of the distinction is the United States created by the Articles of Confederation compared to the United States created by the U.S. Constitution. Under the former, the central government was too weak and so the federal structure did not work, even though the states were far more powerful than they were under the Constitution. The result was anarchy, chaos and internal conflict. The Constitution provided for a stronger central government, which paradoxically made a stable federal system—with still strong states—both possible and practical.

Unfortunately, what is happening in Iraq today is largely decentralization by entropy, not empowerment and…that is likely to produce renewed conflict in the future.

Unfortunately, what is happening in Iraq today is largely decentralization by entropy, not empowerment and that is the second, related factor that is likely to produce renewed conflict in the future. It is this entropic pull that is causing the fragmentation, or “hyperfragmentation” as Denise Natali has put it, that is now the leitmotif of Iraqi politics. The Sunni have long suffered from a badly atomized leadership, but even that has worsened in recent years, exacerbated by Maliki’s brilliance in targeting any moderate, capable and charismatic Sunni leader who might have unified that community. But now the Kurds, whose leadership once consisted of Mas’ud Barzani and Jalal Talabani and no one else, are now increasingly beset by divisions. The long-dormant split between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) has been re-opened, to be joined by a Gorran-KDP split, and splits within each of these parties as well. Even the Shiite leadership is fracturing. Iraqis often like to argue that the Marja’iye (the Shiite religious establishment centered in Najaf) provides Shiites with a unified voice, but if that were ever true, it is proving less and less so. Now, dozens of Shiite figures can claim leadership over important constituencies, including dozens of new militias, many of which operate outside the control of the central government. This centrifugal trajectory simultaneously paralyzes the Iraqi political system and pushes the country toward chaos and renewed conflict.

Specific steps for post-ISIS Iraq

In this context, a new American policy that would have a reasonable prospect of helping Iraq to avoid slipping back into civil war once ISIS is defeated will require the United States to pursue a number of interwoven courses of action.

Forge a new national reconciliation agreement. There is simply no way around this foundational requirement. Iraqis need a new power-sharing agreement that will allow all of the rival communities, but particularly the Sunni and Shiite Arabs, to begin cooperating again. Without this, the military successes against ISIS will evaporate. In recent months, both the United States and the government of Iraq have trumpeted local reconciliation efforts as a bottom-up substitute for a top-down process of national reconciliation. While such grass-roots efforts can be very useful, historically they are no substitute for high-level reconciliation. Without the latter, local efforts are typically undone by rivalries among senior leaders and the result, once again, is renewed civil war. Yet the United States has made far too little effort to bring Iraq’s senior leadership together, hiding behind Baghdad’s desire to handle this itself and the self-fulfilling prophecy that Iraq’s leaders are too fragmented. The current, Iraqi-led “process” has so far achieved nothing. On the other hand, it is worth noting that in 2007-2008, Ambassador Ryan Crocker faced a similar problem of fragmented leadership, yet he and his team brokered exactly the kind of (informal but effective) national reconciliation that Iraq desperately needs once again.

Push Baghdad and Irbil toward short- and long-term solutions. As noted above, it would be better for both Arab Iraqis and Iraqi Kurds if Iraqi Kurdistan were a separate country. Unfortunately, getting to that point without largescale violence will be very difficult. There are borders to be negotiated, populations to be consulted, and foreign powers to be placated (or stonewalled). Moreover, in the near term, Kurdish political, economic and security needs may require a closer relationship with Baghdad rather than a more distant one. The Obama administration has put considerable effort toward handling these immediate problems and has helped achieve a certain amount of success. However, without the framework of a long-term plan that creates the circumstances for peaceful Kurdish secession (along the lines of the Czechoslovak model) these near-term gains will erode and eventually collapse as they have so regularly in the past.

Help Baghdad regain the basic capacities of governance. Even the most extreme advocates of federalism in Iraq recognize that the central government will have to retain certain powers and prerogatives because they are responsibilities that only the central government can realistically discharge. This starts with the role of defending Iraq from external attack—and helping its governorates and regions defend themselves against major internal security threats. It means helping Baghdad regain its Weberian monopoly on the use of violence, including demobilizing the Hashd ash-Shaabi (the Militias created in 2014 after the fall of Mosul) and/or integrating them into the formal Iraqi security forces. Only after that has happened can the central government then delegate part of it to the internal security forces of its governorates and regions. It also entails the ability to conduct basic functions like gathering revenue and spending it on nationwide services like power generation and distribution, infrastructure improvements, and economic development. That, in turn, requires both wider political reform to ensure a more functional central government overall and more specific reforms to address Iraq’s paralyzed legislature, its corrupt executive branch and its politicized judiciary.

Strengthen the Abadi government. The United States can provide Iraq with guidance and some resources to enact the kinds of reforms enumerated above, but most of that work can only be undertaken by the Iraqi government itself. That places a premium on helping the Iraqi government as best we can and far more than we have over the past eight years, which also raises the question of whether the United States should support the current Iraqi government or push for a different one. Although Haidar al-Abadi has made mistakes as prime minister, he is still the best we are likely to get. Of greatest importance, he has a number of highly desirable qualities: He is politically courageous, he is not corrupt (as best anyone can tell), he has a clear (and correct) sense of what Iraq needs to do to escape the civil war trap, and he has shown a willingness and ability to learn from his mistakes. We could have done a lot worse than Haidar al-Abadi. Moreover, replacing him would be more likely to bring to power a worse leader than a better one. Consequently, Washington’s best bet will be to double down on Abadi in the expectation that greater American backing and partnership will enable him to pursue the national reconciliation and political reform that Iraq so desperately needs and that he has repeatedly called for. But that means keeping American skin in the game.

Develop a robust, long-term strategic partnership with Iraq. The Obama administration has proven that its early refusal to invest resources in Iraq—and its perverse claim that doing so was senseless because the United States had no influence there—was wrong. Since 2014, the United States has invested considerable resources in Iraq, including 5,000 ground troops, largescale weapons deliveries, a major air campaign, and significant financial assistance, and as a direct result now has considerably more influence than at any time since 2011. After the fall of Mosul, the United States should maintain this commitment of resources to Iraq. Ideally, the United States would decrease some aspects of its support (like airstrikes and other fire support) and increase other elements to focus more on the political and economic tasks that need to be accomplished after the defeat of ISIS, which are arguably more challenging than the military task of liberating Iraq.

Retain and rebuild the American military presence. Ideally, the United States would keep about 5,000 to 10,000 ground troops in Iraq. In terms of missions, these personnel are needed to thoroughly rebuild the Iraqi Security Forces—as the United States finally did in 2007-2009—with large numbers of U.S. personnel training, advising, partnering and accompanying Iraqi forces down to company level or lower. As part of this, it would be helpful to have American combat battalions, or even brigades, regularly rotate into Iraq to exercise with Iraqi forces. The United States should retain a large Special Operations Forces Counterterrorism force to help Baghdad with the (inevitable) residual terrorist problem that will persist for some time even under the best of circumstances after the fall of Mosul. Further troops would be necessary for force protection, medical support, transportation, communications, and other administrative and security tasks. In addition to carrying out these key missions, the initial size of the force will also be important from a psychological perspective. The Iraqis need to believe that the United States is not abandoning them again, and that the American military presence left behind after the defeat of ISIS is large enough to prevent the country from coming apart at the seams or its government from using force against any of its constituent communities. While even a 10,000-man force would have only a very limited prospect of playing that role in practice, history has demonstrated that in post-conflict scenarios, the symbolic role is of far greater significance than actual military capability as long as the peacekeeping force is believed to have some degree of capacity and a willingness to employ it.4