Kenneth M. Pollack's Blog, page 12

February 14, 2012

Shifting Sands in the Middle East

In our chapter in The Arab Awakening: America and the Transformation of the Middle East on the changes to the regional balance of power in the Middle East, Daniel Byman and I warned that the internal changes taking place within so many of the countries of the Arab world as a result of the great Arab awakening could cause various realignments to the geo-politics of the region. One of the possible realignments we noted was a possible deepening of the Sunni-Shi’a divide. Unfortunately, a variety of recent events seem to suggest that that may be what is happening.

Syria continues to descend deeper into civil war. One should never count out the Asad regime, if only because the Alawi community in which it is rooted believes they will be slaughtered by the majority Sunni population if they lose power and they control many of the key military and security formations in the country. That’s why we have seen so many Syrian military formations remain cohesive and willing to inflict heavy bloodshed on civilians. It could be enough to allow the regime to prevail, and the massacres taking place in Homs may presage just such a bloody crackdown, one very much along the lines of the infamous massacre Bashar al-Asad’s father conducted against a similar Sunni opposition at Hama thirty years ago.

If the regime can’t crush the opposition quickly, the likely alternative scenario is protracted civil war as the largely Sunni opposition battles the residual forces of the Alawi minority and potentially other groups as well.

Meanwhile, next door in Iraq, the country is teetering on the brink of renewed civil war as well. Even before the last American troops departed, Prime Minister Maliki triggered a severe crisis by reacting to a terrorist attack purportedly aimed at him by going after a number of the top leaders of his principal rival, the largely Sunni Iraqiyya party. The immediate tensions have abated somewhat, largely because Iraqiyya felt compelled to end its boycott of the government only because its ministers could not afford to abandon their patronage networks in the ministries they control—an important source of leverage for the prime minister.

But this crisis was a product of the deeper, structural problems in Iraqi politics—problems that were only beginning to be addressed before the premature withdrawal of American troops tore the cast from the Iraqi body politic long before its shattered bones had properly healed. Although Maliki was surprised by the response from both the Kurds and the Shi’i Sadrist trend—both of whom sided unexpectedly with Iraqiyya—he largely won this round, and continues to consolidate power and refuse to make concessions to his political rivals in ways virtually guaranteed to produce future crises. With American peacekeepers now gone, it is only a matter of time before one or another such crisis pushes Iraq back into civil war itself.

As if that wasn’t bad enough already, the civil war in Syria appears to be feeding the flames in Iraq in a way common to civil wars—a topic Daniel Byman described in his chapter on civil wars. A trickle of refugees is now flowing from Syria to Iraq. In future weeks, we could see Syrian opposition fighters seeking sanctuary among their Sunni tribal brothers on the Iraqi side of the border. Indeed, most of Iraq’s Sunnis want to aid the Syrian opposition, just as most Iraqi Shi’a feel a similar sense of solidarity with the Alawis—and why the Iraqi government has been so despicably supportive of the Asad regime.

Of course, both of the regimes in Iraq and Syria are supported by Iran, Damascus willingly and Baghdad grudgingly. That is both a product of their common Shi’a identity and an element reinforcing their own chauvinistically pro-Shi’a policies.

The real danger is that none of this has been lost on the Sunni Arab states of the region, including the Saudis, Jordanians, Egyptians and others. They have long feared a “Shi’a crescent” stretching from Hizballah in Lebanon through Syria through Iraq to Iran or even Bahrain. While this geo-strategic concept is greatly exaggerated at present, it is more accurate than it was five years ago, and the more that the Sunni states treat these countries as if they are a single strategic entity, the more that they will create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Image Source: © Stringer . / Reuters

February 2, 2012

Iran and Syria: A Tale of Two Crises

Event Information

February 2, 2012

10:00 AM - 11:30 AM EST

Falk Auditorium

The Brookings Institution

1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW

Washington, DC

Register for the Event

A year after the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt ushered in the Arab awakening, the United States still faces the difficult task of forging a new strategy for a new Middle East. While regimes in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya eventually fell, the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad has clung to power with grim resolution. The regime has slaughtered its people and ignored pressure from domestic, regional and international actors. Meanwhile, Iran has viewed the Arab Spring as a mixture of opportunity and threat, all the while resisting fierce international demands to end its nuclear enrichment program. In recent weeks, the potential for escalation with one or both of these countries has captured the headlines while the relationship between them has largely been left to the back pages.

On February 2, the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings hosted a discussion to assess the ongoing crises with Syria and Iran, the potential for escalation, and America’s role in the situation. Panelists included Saban Center Senior Fellows Suzanne Maloney and Michael Doran, as well as Andrew Tabler, the next generation fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Brookings Senior Fellow Kenneth Pollack, director of the Saban Center, provided introductory remarks and moderated the discussion.

After the program, panelists took audience questions.

Video

Syrian Civil War a Regional ThreatIranians Feel Under SiegeNew Media and the RevolutionUN Action to End Syrian Regime May Fail

Audio

Iran and Syria: A Tale of Two Crises

Transcript

Uncorrected Transcript (.pdf)

Event Materials

20120202_iran_syria

Participants

Panelists

Andrew Tabler

Next Generation Fellow

The Washington Institute for Near East Policy

January 31, 2012

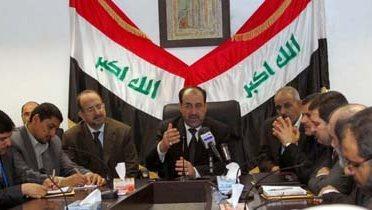

The Maliki Dilemma in Iraq

The recent decision by the largely Sunni Iraqiya party to end its boycott of parliament would seem like an end to Iraq’s crisis. It isn’t. At best, it is a lull.

The crisis that engulfed Baghdad before the last American soldier had even left Iraq was a product of structural problems in Iraqi politics that this week’s events have not even begun to address. However, the Iraqiya decision creates a new opening to begin a process that could eventually deal with these underlying problems. If all sides seize that opportunity, there will be real hope for Iraq. If, as seems more likely, they don’t, Iraq will lurch from crisis to crisis and eventually end up in civil war, an unstable dictatorship or a failed state.

It is important to understand what actually happened this week. Iraqiya ended its parliamentary boycott but not its boycott of meetings of the Council of Ministers. The parliament is due to consider Iraq’s annual budget, and the Iraqi leadership felt it would be disastrous for their party and the communities they represent if they were not present to ensure that they received their fair share of Iraq’s governmental pie. Iraqiya has not ended its ministerial boycott of Council of Ministers meetings, with the result that its ministers are still under suspension by Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, and it has threatened to withdraw from the parliament again if the prime minister does not end his attacks on them.

Read the full article »

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: The National Interest

Image Source: © Mohammed Ameen / Reuters

January 30, 2012

The Revolt in Syria Could Easily Spread to Other Middle East Countries

It’s impossible to know how bad the Middle East is going to get this year. There is mounting evidence to suggest that it could get really bad. Of course, worst cases tend to be mercifully rare, and so we can reasonably hope that the region won’t get as bad as it seems like it might. Then again, this is the Middle East we’re talking about, and in the Middle East, the worst case is unfortunately often the most likely case.

One aspect of how bad the Middle East could get this year lies in the confluence of events in Syria and Iraq.

A few weeks ago, a well-connected Saudi told me, “We see the Syrian civil war and the [coming] Iraqi civil war as the same, and we will treat them as the same.” He explained his point this way: from Riyadh’s perspective, there are Iranian-backed Shia governments in both Syria and Iraq that are oppressing their Sunni populations—Sunni populations that Saudi Arabia and other Sunni Arab states feel increasingly determined to support. He even reminded me that the Sunni tribes of eastern Syria were the same as those of western Iraq. Tribes like the Jubbur and Shammar span the border. So providing money and weapons to the Sunni tribes of eastern Syria is effectively the same as providing money and weapons to the tribes of western Iraq.

Who knows if my interlocutor spoke for the Saudi government. His words seem consistent with Riyadh’s world view and with the approach the Saudis were threatening to take back in 2006, during the darkest days of Iraq's civil war. But as my friend Greg Gause likes to say about understanding the Saudis, the problem is that “those who know don’t talk, and those who talk don’t know.” Still, even if he was wrong, he could still be right.

By any measure, Syria has already crossed the threshold of civil war, and the situation is likely to get worse before it gets better (if it gets better). The Assad regime, and the Alawi Shia community that stands behind it, have shown absolutely no willingness to step down or compromise and appear utterly determined to use as much violence as necessary to stay in power. Indeed, most reports indicate that the Alawis fear that if the regime falls, they will be slaughtered by the Sunni majority they have oppressed for more than 50 years. Consequently, they plan to fight as hard as they can and kill as many as they must to retain power. For its part, the opposition Sunni majority has refused to be cowed by the regime’s violence and is gaining in its own ability to wage war against the regime.

This is not a recipe for peaceful revolution such as we saw in Tunisia and (mostly) Egypt. It is a recipe for deepening conflict, like Libya or Yemen or worse. Unless the regime finds a way to greatly ratchet up the violence and so crush the opposition quickly—or an external great power decides to intervene in force and so snuff out the conflict altogether—the most likely scenario will be a bloody, protracted war.

We should expect that spillover from Syria—which has already affected Turkey, Lebanon and to a lesser extent Israel—will worsen and will also affect Iraq and Jordan.

One of the biggest problems with such intercommunal civil wars is that they don’t stay contained within the borders of the state. Spillover from civil wars is an inevitability, although it can range from quite mild to very severe. Unfortunately, Syria has all the hallmarks of being on the worse end of the spectrum: porous borders, ethno-sectarian communities that span them, irredentist claims, and longstanding grievances with neighbors. My Saudi friend’s point about Iraq gets at exactly this problem, and we should expect that spillover from Syria (which has already affected Turkey, Lebanon, and, to a lesser extent, Israel), will worsen and will also affect Iraq and Jordan.

Spillover from civil wars typically manifests itself in six pernicious ways: terrorism, refugees, economic dislocation, radicalization of the neighboring populations, secessionism, and intervention by neighboring states. In 2006, Iraq was creating all six of these problems for the other states of the Persian Gulf—conjuring widespread panic that the Middle East was going to hell in the proverbial hand basket—only to see those fears abate when the United States changed its strategy and, with the “surge,” successfully suppressed the violence and the civil war. At their worst, civil wars in one state can cause civil wars in another: civil war in Lebanon led to civil war in Syria in 1976-82, the Rwandan civil war sparked the Congolese civil war of the 1990s, just as civil war in Afghanistan is pushing Pakistan to the brink of civil war today (and might push it over in future). Civil war can also lead to regional war as neighboring states intervene in the country in conflict to protect their own interests and prevent their regional adversaries from gaining an advantage: the Congolese civil war invited intervention by seven of its neighbors, Lebanon led to an Israeli-Syrian overt fight followed by a proxy war, Afghanistan led to a covert war between Russia and Pakistan (backed by the United States) and there are numerous other cases along these lines.

Not that Iraq needs any help finding its way back to civil war. It is doing just fine marching smartly down that path all by itself. Despite the progress made in 2008-09, Iraq still has deep structural flaws in its political system that were not fully addressed during the period after the surge when the country made the greatest political progress. The withdrawal of American troops before those flaws were fully addressed has not only revealed the depth of the problems but set back the progress considerably. Baghdad is deeply enmeshed in a crisis, and even if the current situation can somehow be defused, unless all sides show a willingness to compromise and address these deeper issues in a way that they haven’t since the withdrawal of U.S. forces began, crisis will likely follow crisis and the country will end either in civil war, an unstable dictatorship (that will lead to civil war of one kind or another), or a Somalia-like failed state with its own lawlessness and violence.

The prospects for Iraq to muddle its way out of the civil-war trap alone were always daunting, but they take on new seriousness when one considers the likely impact of spillover from a Syrian civil war. Almost invariably in civil wars, armed militias look for sanctuary in neighboring states—particularly those where they have ethnic, religious, tribal, or even political brethren on the other side of the border. The worse the violence gets in Syria, the more that Sunni tribes in Syria fighting against the Alawi Shia regime will look for sanctuary and succor from their brothers in Iraq. Their brothers in Iraq are already contemplating a new conflict against the Shia-dominated regime in Baghdad, and may well look for assistance from their Syrian brothers. Meanwhile, the more that the Saudis, Jordanians, Emiratis, Kuwaitis, and Turks see both of the regimes in Damascus and Baghdad as Iranian puppets (which they all do already to a greater or lesser degree) the more that they will arm the Sunnis in both countries, isolate the regimes of both countries, and possibly even try to push back on the Iranians directly.

The dire warnings of a great Sunni-Shia war that seemed like ridiculous fear-mongering just a few years ago could well become a tragic reality if the Sunni Arab states become determined to prevent Iran from retaining its ally in Damascus and creating a new one in Baghdad. At the very least, their competition for Syria and Iraq, which is already beginning to heat up, is likely to make the situation in both countries worse. At its worst, such efforts to wage a proxy conflict across both countries might apply enough heat to virtually fuse the two civil wars, which would add tremendous fuel to both fires and make it much harder to extinguish either.

How bad could it get in the Middle East? Potentially pretty bad. We have tended to fret about developments within each country, and have at times reassured ourselves that the situation won’t get too bad because of restraints inherent in each country’s situation. But by mentally compartmentalizing them, we may be underplaying the real potential for problems. We must be awake to the possibility, even likelihood, that the problems of Iraq, Syria, the Gulf, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel-Palestine, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, etc. could interact to produce a whole that is even worse than the sum of its parts. And like civilization itself, it might all start on the banks of the Euphrates.

Authors

Publication: The Daily Beast

January 17, 2012

Are We Sliding Toward War With Iran?

With so much alarming going on in the Middle East, it’s hard to keep track of everything that seems to be going wrong. No sooner had the Libyan civil war ended than another erupted in Syria. Iraq appears determined to follow, and perhaps overtake their Syrian neighbors. Egypt remains locked in a multi-sided struggle among the military, the Islamists and the secular liberals. And disturbing reports of low-level, but growing unrest in Saudi Arabia have begun to emerge.

Amid all of this, the one place that the United States has resolutely marched forward—or perhaps been dragged by the Congress and our European allies—has been in applying ever greater pressure on Iran. But if the Obama administration’s forward progress is clear enough when it comes to its Iran policy, its ultimate destination is not. The sanctions against Iran may well succeed on their own terms while producing regrettable, if unintended, consequences.

The latest salvo against Iran came a few short weeks ago, when President Obama signed into law the new Defense Appropriations bill, in which Congressional conservatives had tucked new, draconian sanctions prohibiting transactions with Central Bank of Iran (CBI), or anyone else doing business with the CBI. The importance of these sanctions is that prohibiting transactions with Iran’s Central Bank would preclude long-term oil sales contracts. If no country were willing to deal with the CBI, Iran would be forced to sell its oil either only to countries and companies willing to buck such U.S. sanctions, or rely on spot market sales for cash—an extremely inefficient method that would cut heavily into Iranian oil revenues. Some analysts, in fact, estimate that this could lead to a reduction of Iranian oil revenues by as much as one-third—and since Iran is heavily dependent on oil revenues, this could have a major impact on the Iranian economy.

Now that would seem to be a good thing, right? Maybe, but maybe not. Certainly the Iranian regime has shown absolutely no inclination to halt (let alone give up) its nuclear program in the face of previous sanctions, which are already having a serious impact on the Iranian economy. The hope is that going after Iranian oil revenues in this fashion would apply so much pressure on Iran’s economy, causing rampant inflation and even economic collapse, that the regime will have no choice but to compromise and accept international demands related to its nuclear program.

The problem is that these sanctions are potentially so damaging that they could backfire, creating at least three sets of consequences that would leave the United States in a worse position, whatever the impact on Iran.

Read the full article »

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: The New Republic

Image Source: Reuters

December 24, 2011

Understanding the Iraq Crisis

We were all wondering how long it was going to take after the withdrawal of American troops for Iraq to face its first major political crisis. But I seriously doubt that anyone would have dared to predict that it would begin even before the very last U.S. soldiers had crossed the borders with Kuwait. Nevertheless, here we are. While the American media was running endless stories about the “end of the Iraq war,” the Iraqis were busy gearing up for the next round.

Make no mistake about it: the current crisis, manufactured by Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki for reasons that only he knows for sure, is of seminal importance for Iraq. Right now, it seems far more likely to end badly rather than well. And if it ends badly, it could easily usher in renewed civil war, a highly unstable dictatorship, or even a Somali-like failed state. Not only would this be a humiliation for the Obama administration—which justified the withdrawal of American troops by insisting that Iraq was well on the way to democratizing and did not need an ongoing U.S. peacekeeping presence—it would be a major threat to American vital interests in the Persian Gulf region.

What Happened?

Asking about the origins of this crisis is like asking about the origins of the Arab-Israeli dispute: it all depends on your perspective. Without getting into the painful history of problems that cropped up after Iraq’s 2010 national elections, it seems reasonable to date this one to the October-November time frame when various Sunni leaders and communities began to openly agitate for local autonomy by pursuing the “federal region” status outlined in Iraq’s constitution and meant to provide the Kurds with the autonomy they demanded. Fearful of Maliki’s arbitrary and at times unconstitutional rule, his mass purges of Sunni military officers and civilian officials, and the endless gridlock of politics in Baghdad, the majority-Sunni provinces of al-Anbar, Salah ad-Din, Ninewah and Diyala all began to discuss the idea of applying for regional status to distance themselves from Baghdad and the Maliki government. (And to make matters worse, their clamor appears to have helped convince unhappy Shi’ah in oil-rich al-Basrah province to begin to demand the same.)

Maliki reacted in unfortunately characteristic terms. He denounced all such talk as illegal and warned that any moves toward federal regions would be blocked as being unconstitutional (despite the explicit provisions of the constitution to do so.) Maliki may or may not be deliberately maneuvering to make himself the new dictator of Iraq but his political instincts are very problematic regardless. He is paranoid and prone to conspiracy theories. He is impatient with democratic politics and frequently interprets political opposition as a personal threat. And when faced with opposition, he often lashes out, seeing it as an exaggerated threat that must be immediately obliterated through any means possible, constitutional or otherwise. This has been his modus operandi and that is how he responded to the Sunni clamor for federalism.

First, he arbitrarily limited the size of the security details assigned to key leaders of the Iraqiyyah party—his most important opposition and the party that tends to represent the Sunni community (although it is led by the Shi’ah former prime minister, ‘Ayad Allawi, and does include a number of other Shi’ah as well.) Then, his personnel arrested several of Sunni Vice President Tariq al-Hashimi’s bodyguards. After extensive interrogation (which the Sunnis insist included torture), Maliki’s people claimed that Hashimi’s bodyguards had admitted that Hashimi was behind a failed terrorist attack on the Iraqi parliament, the Council of Representatives (CoR) which Maliki’s people insist was really aimed at the Prime Minister although the evidence of this is non-existant. In response, even before he stepped off the plane that brought him back from his triumphal trip to the United States, Maliki ordered Iraq’s international zone (the former “Green Zone”) locked down, Americans were forbidden entrance, and armored vehicles were deployed around Hashimi’s house as well as the house of Finance Minister Rafe al-Issawi, one of the most important Anbari politicians in Baghdad and one of the most decent men in the government.

From there things went from bad to worse. Hashimi and Issawi were delayed and searched before flying to Irbil for a pre-arranged meeting. Maliki announced that Sunni Deputy Prime Minister Saleh Mutlaq—a vocal proponent of Sunni regionalism, who had called Maliki a dictator in the run-up to the crisis—would be forced out of office. Although the Constitution clearly stipulates that this can only happen with the approval of the CoR, Maliki announced that only the Cabinet needed to approve it. Meanwhile, Maliki’s people began changing their allegations against Hashimi, abandoning the claim that he was tied to the failed bombing of the CoR and alleging instead that he was responsible for other terrorist attacks dating back to 2008, although they offered no explanation as to why these charges had never been mentioned, let alone investigated, at any point in the past, and why now they suddenly constituted probable cause for an arrest warrant. Maliki demanded that the Kurds hand Hashimi over to his security personnel.

Iraqiyyah chose to respond by withdrawing its members of Parliament from the CoR and its ministers from the cabinet. On December 21, Maliki fired back. He held a press conference in which his tone was entirely caustic and uncompromising. He insisted that the Kurds hand over Hashimi so that he could be arrested and tried—as they had tried Saddam Husayn, the prime minister helpfully noted. He repeated that Mutlaq had been deposed and that the decision of the Cabinet had to be respected. And he warned that if the Sunnis were unwilling to act according to (his version) of the Constitution, that they could withdraw from the government and he would form a majoritarian government of Shi’ah and Kurds without them, something his advisors have been discussing since the spring. The next day, Maliki’s people announced that Rafe al-Issawi was also being investigated for ties to terrorists, these going back to events in 2006, although once again they refused to provide any evidence or even an explanation of why this matter was suddenly being pursued, and pursued as if the fate of the nation depended on it, after five years.

A Bevy of Bad Outcomes

Like so many crises, especially Iraqi crises, there is really only one good outcome for this one. On the other hand, there are a lot of possible bad outcomes, and based on events so far, a betting man would probably put his money on one of them. The only good solution would be for Maliki to back down, stop making new accusations, and tone down his rhetoric. He would need to find a face-saving way to do so, perhaps through the vehicle of the national conference suggested by Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) President Mas’ud Barzani. It would mean reinstating Mutlak (or another senior Sunni chosen by the Iraqiyyah leadership); allowing the charges against Hashimi to fall into the same limbo that Maliki conveniently placed the murder charges against his new ally, Muqtada as-Sadr; and forgetting his claims about Rafe al-Issawi. It would also mean trying to negotiate some kind of compromise agreement on some issue of importance to the Sunni community (like the Amnesty law that has made a little progress in the CoR in recent months).

Barring that, the result is likely to be trouble. In that case, Maliki would almost certainly succeed in accomplishing his stated goals, and in so doing would make himself a de facto dictator. If he succeeds in removing Saleh Mutlak (and especially if his unquestionably unconstitutional move of simply deposing Mutlak without CoR approval stands); if he is able to arrest and try Hashimi, or even if he succeeds in forcing Hashimi into permanent exile by allowing the arrest warrant to stand; and if he succeeds in arresting and trying Rafe al-Issawi, he will have successfully gutted the Sunni opposition. He will not need to arrest any other Sunni leaders, although given his propensity for mass arrests, he might do so anyway just to ensure that they could not cause him any trouble. But every other Iraqi political leader will know that he can do to them what he did to Mutlak, to Hashimi and to Issawi whenever he wants and no one will be able to save them since no one could save Mutlak, Hashimi or Issawi.

In those circumstances, the key question is how the Sunni community reacts to the establishment of such a new de facto, Shi’i dictatorship. It seems unlikely that they would simply acquiesce, although even in the unlikely event that they did so, it would be no guarantee of stability for Iraq. It is worth remembering that since Iraq gained (nominal) independence from the British in 1932, the country was wracked by the highest number of coup d’etats in the Arab world. The country proved almost impossible to govern for one autocrat after another, each of which found himself locked in various battles (often literally) with one unhappy group after another. Saddam Husayn was, arguably, the only Iraqi dictator to create a somewhat stable autocracy—and was certainly the only one who was able to rule continuously for more than a few years—and he was able to do so only by creating a Stalinist totalitarian state and employing near-genocidal levels of violence against his own people. Especially because of the recent experience of the Sunni insurgency and the Iraqi civil war, the likelihood is that a Maliki dictatorship would prove short-lived and unstable, and could easily end in a new civil war.

It is far more likely that the Sunnis won’t acquiesce to Maliki as dictator, even if merely in an opaque de facto sense. Then the question will simply be whether they decide to revolt and shift over to violent opposition suddenly and massively, or more gradually. Either way, we would likely see the Sunni-dominated provinces of al-Anbar, Diyala, Salah ad-Din and Ninewah distance themselves from the government, demand regional status, cease cooperation with Baghdad, and prevent Iraqi government officials—likely including federal police and army formations—from gaining access or moving around freely in their territory. Terrorist attacks would increase in both intensity and geographic scope as more money and recruits poured in from the Sunni community of Iraq itself, and from neighboring Sunni states like Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Eventually, those terrorist attacks would expand into a full-blow insurgency and, especially if (as seems most likely) the Iraqi army were to fracture along ethno-sectarian lines allowing Sunni soldiers to bring their training and heavy weaponry with them to the Sunni side, you could see pitched battles between government forces and well-organized Sunni militias. Iraq would once again find itself sliding into all-out civil war, this time without the prospect that the United States could or would save them from themselves.

The Critical Role of the Kurds

A great deal now rests on the Kurds, and particularly on Barzani. Indeed, they may be the only internal or external actor with the ability to derail this crisis. Although it is impossible to know Maliki’s full calculus, it seems unlikely that he would be looking to take on both the Sunnis and the Kurds simultaneously at this moment. Indeed, part of his thinking is almost certainly that, for a variety of reasons discussed below, the Kurds are likely to stand aside at this point, allowing him to divide and conquer—cut the Sunnis down to size without having to face the Kurds as well. Thus, if the Kurds were willing to go to Maliki and tell him, in private, that they will fully support the Sunnis; that they are willing to withdraw their parliamentary support from the government, bring about a vote of no confidence, vote against the government (which along with Iraqiyyah would cause it to fall), and would even fight alongside the Sunnis if it came to that, it seems more likely than not that Maliki would be willing to back down. He could use Barzani’s proposed national conference to first suspend his attacks on the Sunni political leadership and then allow a face-saving set of compromises to work out. This may be the only good way out of the current mess.

However, it is just not clear that the Kurds will do so for a variety of reasons that likely were part of Maliki’s calculus all along. First off, Iraqi President Jalal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan—the principal partner of Barzani’s Kurdish Democratic Party—is under tremendous pressure from Iran. Iranian troops regularly shell PUK villages in eastern Kurdistan, and Iranian intelligence operatives have infested PUK areas making it very difficult for the PUK to oppose Tehran’s wishes, and Tehran is undoubtedly thrilled with Maliki’s actions because Sunni-Shi’i conflict in Iraq simply makes all of the Shi’i groups ever more dependent on Iran. This is why it will have to be Barzani who takes on Maliki: Talabani simply may not be in a position to do so, and he may even try to dissuade Barzani from doing so.

Second, the Kurds feel completely abandoned by the United States. They have repeatedly asked the Obama Administration for guarantees that it will back their security against any potential threat from the central government in Baghdad, and the Obama Administration has given them nothing. As a result, they now believe that they truly do not have a good option to pursue independence (since to do so they would need American backing against Iran, Turkey and Baghdad—all of which would oppose such a move ferociously) and therefore must remain a part of Iraq for the foreseeable future. That means they have an incentive to get along with Maliki and the central government.

Finally, there is the recent deal signed between the KRG and Exxon. Almost none of the oil companies who signed deals to help develop Iraq’s massive southern oil fields were happy with those deals. The contracts were extremely stingy and, especially given the political instability in the south, many of the companies were ambivalent at best about going through with them. Exxon has led the way, signing a deal to develop several fields in KRG territory and territory that the KRG claims but is disputed by the central government and other groups. In so doing, Exxon thumbed its nose at Baghdad, provoking an irate response from Maliki. Since then, a number of other international oil companies (IOCs) are thinking of following Exxon’s lead and are reportedly exploring options with the KRG. From the Kurds’ perspective, this is fantastic: they believe that they have Maliki and his government over a barrel (pardon the pun) and can use such a shift by the IOCs to force Baghdad to make key concessions on the long-stalled hydrocarbons law and possibly on other, even more sensitive issues, like the status of Kirkuk. Although the Kurds may well be exaggerating the extent of the leverage they have as a result of this turnabout, their perception that they have Maliki right where they want him perversely creates an opportunity for Maliki against the Sunnis since the Kurds will be loath to squander their perceived advantage over Maliki to save the Sunnis. Indeed, they may even believe that they can demand Maliki’s acquiescence on their key issues (Kirkuk, the hydrocarbons law, etc.) in return for their agreement to stay on the sidelines during this crisis. They may well stand aside, convincing themselves that Maliki won’t go too far, in expectation that by doing so, they can get everything they have always ever wanted from Baghdad in return.

American Impotence?

The future of Iraq is hanging by a thread, but no one knows whether the thread will break, and if so, where the country will land—civil war? A new, unstable dictatorship? A failed state? A messy partition? All of these are plausible scenarios and none of them will be happy outcomes for Iraq, for the region, or for the United States for that matter.

For that reason, it is particularly alarming that events so far appear to indicate that the withdrawal of American troops and the administration’s failure so far to build up alternative sources of leverage have left the United States with little ability to influence Iraq’s future course. Senior American officials, including Vice President Biden, the administration’s point man on Iraq, have been imploring Prime Minister Maliki to de-escalate, to stop mounting new attacks on the Sunni leadership, and to rein in his rhetoric. Maliki has done none of those things. Quite the contrary, he continues to make new accusations, he continues to demand that the KRG hand over Hashimi, he is now threatening to exclude the Sunnis from the government altogether, and he has expanded his attacks to include Finance Minister Issawi. He certainly does not seem to be heeding Washington’s demands, pleas or suggestions.

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Image Source: © Ho New / Reuters

December 22, 2011

Iraq Back on the Brink: Maliki's Sectarian Crisis of His Own Making

At least the Nixon administration got something of a “decent interval” before North Vietnam betrayed their exit strategy from Southeast Asia.

The Obama administration did not even get that from the Iraqis. Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki did not even wait till the last American troops had crossed the line into Kuwait—not even till he had gotten off the plane that brought him back from his recent trip to Washington—to mount a brazen and phenomenally dangerous coup against his primary political foes. For those who have not been keeping up with current events, a cursory overview of the crisis in Baghdad may be in order. Throughout the fall, Iraq’s four Sunni-dominated provinces (al-Anbar, Salah ad-Din, Ninewah, and Diyala) have been signaling that they will seek regional status, as allowed by the federalism procedures of Iraq’s constitution. Doing so would allow them to distance themselves from Baghdad, which the Sunnis see as increasingly dominated by an increasingly autocratic prime minister in Maliki. As if to prove their point, Maliki has insisted that any such moves would be illegal, despite the fact that they are clearly mandated by the constitution.

Last week, on the heels of his trip to the White House, Maliki decided to take action. He accused Sunni Vice President Tariq al-Hashimi (a recent, but now vocal, convert to Sunni federalism) and Finance Minister Rafe al-Issawi, both prominent leaders of Maliki’s main political rival, the Iraqiyyah party, of being behind a failed terrorist attack that Maliki’s people insist was aimed at the prime minister himself—despite the absence of any evidence either that it was aimed at him or that Hashimi and Issawi were involved. Maliki deployed tanks to both of their houses and then issued a warrant for Hashimi’s arrest.

He then announced that the cabinet had deposed Deputy Prime Minister Saleh Mutlaq, another important Sunni leader of Iraqiyyah and another proponent of Sunni federalism. Again, the Iraqi constitution clearly stipulates that removing the deputy prime minister requires a vote in parliament, and Maliki and his staff have simply asserted that this is not so. The prime minister also aired videotaped “confessions” by two of Hashimi’s bodyguards, who had previously been arrested by Maliki’s security people, in which they claimed that Hashimi was involved in various acts of terrorism dating back to 2008. Not surprisingly, various Sunnis insist that the confessions were produced by torture.

Sunnis (and Kurds and many other Iraqis) now see a prime minister acting in arbitrary and blatantly unconstitutional fashion, manufacturing paper-thin charges against his most important political adversaries to remove them from power. It is what the Sunnis (and all of Iraq’s other minorities) always feared, and why they wanted American troops to stay. It has pushed Iraq to the brink of political crisis with shocking speed.

The crisis is extremely dangerous for the United States. Dangerous for President Obama politically, because his administration’s risky decisions regarding the withdrawal of American troops from Iraq were based on their determination that Iraq was stable and democratizing and therefore no longer needed a large U.S. military presence. Dangerous for the country’s vital interests, because Maliki’s brazen attack on key Sunni political leaders has an uncomfortably high likelihood of sending Iraq spiraling into a new civil war. Indeed, historically, states that experienced a major intercommunal civil war like Iraq did in 2005-2007 relapse 33 to 50 percent of the time. And civil war in Iraq would threaten not only Iraq’s own oil production, but that of neighboring states like Kuwait, Iran, and even Saudi Arabia. (Just another reason that we, and the rest of the developed world, need to kick our oil addiction....)

One of the most frightening aspects of the crisis has been that although American interests are clearly threatened, events so far suggest that we have almost no ability to guide its outcome.

With the withdrawal of American troops, Prime Minister Maliki and his coterie are flat-out ignoring Washington’s requests, demands, and desires. Starting on December 17th, Vice President Joe Biden, Director of Central Intelligence David Petraeus, Assistant Secretary of State Jeff Feltman, and Ambassador Jim Jeffrey have all weighed in with a wide variety of Iraqis, all to no effect. The U.S. has been urging Prime Minister Maliki to tone down his attacks, stop making inflammatory accusations, desist from taking any more incendiary steps, and generally de-escalate the crisis.

Instead, Maliki has done the exact opposite. On December 21 he gave a press conference in which he demanded that the Kurds hand over Vice President Hashimi for arrest, insisted that the (unconstitutional) decision to depose Deputy Prime Minister Saleh Mutlaq be respected, threatened wider action against other Iraqiyyah party leaders if they do not cooperate with him, and threatened to rule as a majoritarian government without the Sunnis. Then, on December 22, he widened his attacks to charge Finance Minister Issawi, a prominent Sunni from Anbar and one of the most decent men in the Iraqi government, with collaboration with terrorists back in 2006. It would be difficult to describe these as the actions of a man acceding to American wishes to defuse the situation.

In retrospect, Maliki’s trip to America at the beginning of the month takes on a very different light. He clearly hoped to convince most Iraqis that he retained a very strong relationship with the United States—that Washington continued to “back him” in a colloquial sense—something that was obvious even before the trip. The success of his visit, and the administration’s efforts to make relations appear warm and friendly, appears now to have helped Maliki move against his domestic rivals. He certainly evinced no interest in using the trip to secure American help in reconciling Iraq’s fragmenting communities. He bluntly scorned even the suggestion that compromise and reconciliation were necessary. However, Maliki may also have intended the trip as a marker, or even a warning, to the United States: $10 billion worth of U.S. arms sales to Iraq are in the offing—$10 billion worth of American jobs—as long as Washington doesn’t blow it by trying to get involved in Iraqi internal politics.

In other words, Maliki may believe that, if anything, his arms purchases from the United States give him $10 billion worth of influence with Washington and insulation from American pressure. All other things being equal, the Iraqis would undoubtedly like to get the weapons from the U.S., because American arms are now the “gold standard,” and what Iraq’s generals want. But all other things are never equal in Iraq, and politics always lays a heavy hand on the scales. Maliki and his advisers may believe that an economically challenged American administration cannot afford to jeopardize $10 billion worth of sales, and that if Washington were ever to do so, he would simply get his weapons elsewhere. He may well believe (like many others before him) that Iraq’s huge, potential oil wealth puts him in the driver’s seat. In other words, those arms sales are not a source of leverage for the Americans over the Iraqis, but a source of leverage for Iraq over the Americans.

So what is going to happen in Iraq? Who knows.It probably won’t be good. It could easily be disastrous, and the United States is now along for the ride without much say in any of it.

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: The Daily Beast

Image Source: � Mohammed Ameen / Reuters

December 4, 2011

America's Second Chance and the Arab Spring

Egyptians went to the polls en masse on Nov. 28 and Nov. 29 to vote in the closest thing that any of them has ever seen to real elections. Although the final word is not in—either regarding the results or the integrity of the elections—early reports suggest that the vote was mostly fair and free.

But Egypt is still a long way from stable, functional democracy. As Iraq, Palestine, and Lebanon have demonstrated again and again, elections do not equal democracy. Egypt's Islamists—who appear to have garnered as much as 65 percent of the vote—will dominate the new parliament regardless of the role they play in the new Egyptian government, and we do not yet know whether they will wield that power responsibly. Egypt's armed forces remain the most powerful force in the country by far, and they have shown a Hamlet-like ambivalence—demonstrating an ardent desire to surrender power to a new civilian government and a similar determination to preserve their own prerogatives from the era of Egyptian autocracy.

The strong showing of Salafi movements, which appear to have captured approximately a quarter of votes, was the surprise of this round of elections. These Sunni extremists are growing in number and, if the system begins to break down, might try to seize control of the government like modern-day Bolsheviks. Some of Egypt's most popular leaders are dangerous demagogues who could plunge the country into all manner of problems. Democracy is a long road, with many perilous intersections, and Egypt has barely started on its way. What's more, Egypt will likely require considerable political, military, and even economic support from the United States and the rest of the world if it is to make that critical, dangerous, transition successfully.

Read the full article »

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: Foreign Policy

Image Source: Reuters

November 27, 2011

The Egyptian Military Faces Its Defining Hour

On February 11, 2011 we all hailed Mubarak's fall as a new revolution. The truth is that it was less a true revolution than a very popular military coup. It was Egypt's armed forces who decided that Mubarak had to go, and they did so specifically to head off a true revolution, not to inaugurate one. Indeed, the Egyptian armed forces appear to have calculated then that they needed to get rid of Mubarak to save the wider political system he had built—and from which they benefitted enormously. As I examine in my chapter “The Arab Militaries: The Double Edged Sword” in The Arab Awakening: America and the Transformation of the Middle East , Egypt and the rest of the Arab world must balance military strength with civilian leadership to succeed and prosper.

In the 1990s, when Egypt was struggling economically and the Egyptian officer corps was suffering from low wages and even lower prestige, Mubarak granted them carte blanche to supplement their wages and perks from the annual budget by investing in Egypt's economy. The generals did so reluctantly but successfully, using their influence and funds to gain control of large segments of the Egyptian economy (perhaps as much as 25-33 percent by some estimates). This, in turn, became a critical component of their personal wealth and institutional strength. By making the military less reliant on budgetary spending and more dependent on their control of the economy, Mubarak inadvertently cut his own "power of the purse" and gave the armed forces a certain amount of economic independence. He also gave them an incentive to resist far-reaching political-economic change however they could.

As a result, when Egyptians began to take to the streets in January to demand fundamental political-economic change, it galvanized the military to act. They were determined to prevent the kind of change that would endanger their own power and position, including their role in the civilian economy. They decided, for this reason among others, that sacrificing Mubarak was necessary to head off demands for wider, more dangerous (to their interests) change.

Since then the military has tried to pursue two increasingly divergent tracks. On the one hand, they have insisted that they do not want to rule the country and have tried to enable a transition to democracy. On the other hand, they have insisted on maintaining ultimate authority over the transition and have announced that the new civilian leadership would be precluded from exercising authority over certain spheres sacrosanct to the armed forces. In short, they would gladly hand power to a new civilian government but the military would sit above the civilian government and the civilians would not be able to trespass on whatever the military considered important to it.

This approach was always bound to experience severe strains, and was unlikely to work at all. As we noted in The Arab Awakening , this reflects a fundamental dilemma between the "ideal" Turkish model and the real Turkish model. In an ideal world (or some idealized telling of history), the Turkish military was meant to stand apart from politics as the disinterested guardian of the secular, democratic political system, ensuring that no political faction could subvert that system. The reality has been that, up until the last decade, the Turkish military intervened routinely in politics to advance its own narrow interests. The Egyptian military wants to have it both ways, and in recent weeks, Egyptians are increasingly insisting that they cannot.

The events in Tahrir Square are thus a far more profound challenge to the Egyptian armed forces than was Mubarak's fall, stunning though that was. This time around, there is no scapegoat to sacrifice to expiate popular anger. This time, the crowds are demanding fundamental change to the political system, and that the military stand back and allow that fundamental change to occur.

It is why what is playing out now in the streets of Cairo, Alexandria, Suez and other cities is actually of far greater consequence than what happened in February. If the military gives way, it will mean that a fundamental reinvention of the system is now possible—although which direction it takes remains up for grabs. If not, they will have to resort to repression to hold power, and if they succeed in doing so, it will mean the reincarnation of Mubarakism without Mubarak.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces is now finally, truly confronting the ultimate choice between repression and revolution—hopefully peaceful and gradual. And no one knows which they will choose.

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Publication: The Brookings Institution

Image Source: Reuters/Ahmed Jadallah

October 20, 2011

Iraq Troop Withdrawal: Out with a Whimper, Not a Bang

Today's announcement by the president that the United States would be withdrawing all of its combat troops from Iraq by December 31, 2011 per the original terms of the U.S.-Iraq Security Agreement of 2008 was little more than an anti-climax. The writing had been on the wall for all to see for months to come. Unilaterally, the administration decided to offer only 10,000 troops as a residual force when negotiations began in earnest over the summer. This was well below the 20,000-30,000 troops that military experts believed optimum. Just a few weeks ago, the administration then unilaterally decided to cut that number down to about 3,000. There was nothing that 3,000 troops were usefully going to do in Iraq. No mission they could adequately perform from among the long list of critical tasks they have been undertaking until the present. At most, they would be a symbolic force, that might give Tehran some pause before trying to push around the Iraqi government. However, even playing that role would have been hard for so small a force since they would have had tremendous difficulty defending themselves from the mostly-Shi'ah (these days), Iranian-backed terrorists who continue to attack American troops and bases wherever they can.

At that point, it had become almost unimaginable that any Iraqi political leader would champion the cause of a residual American military presence in the face of popular resentment and ferocious Iranian opposition. What Iraqi would publicly demand that Iraq accommodate the highly unpopular American demands for immunity for U.S. troops when Washington was going to leave behind a force incapable of doing anything to preserve Iraq's fragile and increasingly strained peace? Why take the heat for a fig leaf?

Of course, the truth was that the Iraqi government itself had already become deeply ambivalent, if not downright hostile to a residual American military presence. Although it was useful to the Prime Minister to have some American troops there as a signal to Iran that it shouldn't act too overbearing lest Baghdad ask Washington to beef up its presence, he and his cohorts probably believe that they can secure the same advantages from American arms sales and training missions. The flip side to that was that the American military presence had become increasingly burdensome to the government—challenging its interpretation of events, preventing it from acting as it saw fit, hindering their consolidation of power, insisting that Iraqi officials adhered to rule of law, and acting unilaterally against criminals and terrorists the government would have preferred to overlook. All of this had become deeply inconvenient for the government.

Unfortunately, it is the willingness of the government to act in extra- or unconstitutional fashion, to ignore the misdeeds of its political allies, and to employ the power of the state (sometimes illegally) against its political rivals that creates the compelling need for an ongoing American military presence that has now evaporated. The worst elements among the Shi'ah are using their ties to the regime to employ violence for political and economic gain, or simply out of vengeance or fear. Among the Sunnis, more and more talk about the need to re-arm to protect themselves and their communities since the government clearly won't—and is increasingly part of the problem, not the solution. Meanwhile the Kurds see the re-emerging tensions south of the trigger line and ponder whether secession might finally be possible, prudent, even necessary.

Is Iraq doomed to another round of horrific civil war? Not necessarily. Nothing is inevitable. Iraqis might recognize that they are headed for the falls and make the selfless, heroic efforts necessary to turn their ship around. But the history is pessimistic and the trends are worrisome. Nothing they have done so far suggests that they will. America's troops in Iraq—disliked, misunderstood and resented though they were—were Iraq's best shot at achieving a stable, pluralistic, prosperous future. Without them, Iraq is not yet condemned to darkness, but its chance for redemption has dimmed perceptibly.

Authors

Kenneth M. Pollack

Image Source: Reuters

Kenneth M. Pollack's Blog

- Kenneth M. Pollack's profile

- 41 followers