Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 339

January 20, 2020

Why We Try

BEATING THE STOCK market over the long term is no mean feat. Only a tiny proportion of investors—professional or otherwise—manage to do it. So why do so many people think they can?

Meir Statman, a finance professor at Santa Clara University, cites eight key reasons. In a new monograph titled Behavioral Finance: The Second Generation, he slots these reasons into two broad categories—five cognitive and emotional errors, followed by three expressive and emotional benefits:

1. They forget that trading is competitive.

Statman suggests the first mistake that investors make is a so-called framing error. Specifically, investors assume that trading is analogous to an activity such as plumbing. A plumber’s work improves the more experienced he or she becomes. But the analogy with investing is flawed because “pipes and fittings do not compete against the plumber, inducing her to choose the wrong fitting,” Statman writes. A trader, on the other hand, “always faces a competing trader on the other side of his trade, sometimes inducing him to choose the wrong trading strategy.”

2. They don’t compare their returns to the market.

This is another framing error. Many investors, Statman says, frame their returns relative to zero, rather than relative to the market return—the performance they could have earned by investing in a low-cost index fund. “A 15% annual return is excellent,” he says, “but it is inferior when an index fund delivers 20%.”

3. They don’t properly calculate their returns.

Another reason investors mistakenly believe that markets are easy to beat: They tend to form a general impression of their results, instead of properly calculating them. This leads to confirmation errors, whereby they focus on the winners in their portfolio and overlook the losers. A study of amateur investors in the U.S., for instance, found that they overestimated their investment returns by an average 3.4 percentage points.

4. They’re fooled by small numbers.

It’s reasonable, Statman suggests, to form an opinion of a restaurant on the strength of 10 visits: “Seven bad meals out of 10 or even two bad meals out of three might well be all we need for a general conclusion that it is best to forgo dining at that restaurant.” What makes trading different is the random nature of outcomes. Things can either go very well or very badly. It’s perfectly possible for a trader to enjoy a streak of wins, purely because of luck.

5. They’re susceptible to availability errors.

The final error that Statman highlights is often referred to as availability bias. Investors tend to base their opinions on information that’s easily available. Whether it’s someone at the local bar, a colleague at work or a relative at a family gathering, we’ve all had conversations with people who claim to have profited greatly from buying a particular stock or fund. People who share these sorts of stories are often less inclined to disclose the bad investments they’ve made. The same applies to stories in the media. Generally, the funds that are written about are those which have outperformed.

6. They like to gamble.

After articulating the above five errors, Statman turns his attention to what investors want. It’s well known that some of us enjoy gambling. There are those who, even when faced with large losses, keep gambling because they like the buzz so much.

There’s evidence that some investors are motivated by the same sort of enjoyment. For example, a 2018 study of 421 pump-and-dump schemes in Germany found that the average loss for investors was nearly 30%. Yet, during the sample period, some 11% of pump-and-dump investors participated in four or more schemes.

7. They enjoy it as they would a hobby.

It isn’t just the prospect of a big win that makes people try their hand at active trading. In one study, active investors in the Netherlands were asked about their motivations. More of them agreed with the statement “I invest because it is a nice free-time activity” than with the statement “I invest because I want to safeguard my retirement.” A study of amateur U.S. traders by Fidelity Investments found that more than half enjoyed learning new skills and sharing news of their wins and losses with friends and family.

8. They think of themselves as better than average.

The final motivation for active trading, Statman argues, is the need to feel that we’re better than average. This need, he says, is reflected in the way that funds are marketed. He refers to two TV commercials, both for investment companies.

One denigrates index funds as average, and concludes with a man standing on a stage as a sign lights up: “Why invest in average?” In the second ad, the announcer asks, “If passive investing was called ‘don’t try,’ would you still be interested?” The irony: Index investing is, of course, a way of ensuring that you receive returns that outpace those of the typical investor.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He’s a campaigner for positive change in global investing, advocating better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor, which is where a version of this article first appeared. His previous articles for HumbleDollar include Good for You, Better Than Timing and Writing Wrongs. Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He’s a campaigner for positive change in global investing, advocating better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of The Evidence-Based Investor, which is where a version of this article first appeared. His previous articles for HumbleDollar include Good for You, Better Than Timing and Writing Wrongs. Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.

Do you enjoy articles by Robin and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Why We Try appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 19, 2020

Seven Paradoxes

“THE INVESTOR’S CHIEF problem—even his worst enemy—is likely himself.” So wrote Benjamin Graham, the father of modern investment analysis.

With these words, written in 1949, Graham acknowledged the reality that investors are human. Though he had written an 800-page book on techniques to analyze stocks and bonds, Graham understood that investing is as much about human psychology as it is about numerical analysis.

In the decades since Graham’s passing, an entire field has emerged at the intersection of psychology and finance. Known as behavioral finance, its pioneers include Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky and Richard Thaler. Together, they and their peers have identified countless human foibles that interfere with our ability to make good financial decisions. These include hindsight bias, recency bias and overconfidence, among others. On my bookshelf, I have at least as many volumes on behavioral finance as I do on pure financial analysis, so I certainly put stock in these ideas.

At the same time, I think we’re being too hard on ourselves when we lay all of these biases at our feet. We shouldn’t conclude that we’re deficient because we’re so susceptible to biases. Rather, the problem is that finance isn’t a scientific field like math or physics. At best, it’s like chaos theory. Yes, there is some underlying logic, but it’s usually so hard to observe and understand that it might as well be random. The world of personal finance is bedeviled by paradoxes, so no individual—no matter how rational—can always make optimal decisions.

As we plan for our financial future, I think it’s helpful to be cognizant of these paradoxes. While there’s nothing we can do to control or change them, there is great value in being aware of them, so we can approach them with the right tools and the right mindset. Here are just seven of the paradoxes that can bedevil financial decision-making:

There’s the paradox that all of the greatest fortunes—Carnegie, Rockefeller, Buffett, Gates—have been made by owning just one stock. And yet the best advice for individual investors is to do the opposite: to own broadly diversified index funds.

There’s the paradox that the stock market may appear overvalued and yet it could become even more overvalued before it eventually declines. And when it does decline, it may be to a level that is even higher than where it is today.

There’s the paradox that we make plans based on our understanding of the rules—and yet Congress can change the rules on us at any time, as it did just a few weeks ago.

There’s the paradox that we base our plans on historical averages—average stock market returns, average interest rates, average inflation rates and so on—and yet we only lead one life, so none of us will experience the average.

There’s the paradox that we continue to be attracted to the prestige of high-cost colleges, even though a rational analysis that looks at return on investment tells us that lower-cost state schools are usually the better bet.

There’s the paradox that early retirement seems so appealing—and has even turned into a movement—and yet the reality of early retirement suggests that we might be better off staying at our desks.

There’s the paradox that retirees’ worst fear is outliving their money and yet few choose the financial product that is purpose-built to solve that problem: the single-premium immediate annuity.

How should you respond to these paradoxes? As you plan for your financial future, embrace the concept of “loosely held views.” In other words, make financial plans, but continuously update your views, question your assumptions and rethink your priorities.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Cut the Bonds, Got You Covered and An Unkind Act

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Cut the Bonds, Got You Covered and An Unkind Act

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept donations, run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Seven Paradoxes appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 18, 2020

Just in Time

I USED TO THINK anybody could be taught to manage money sensibly. I no longer believe that.

When I was in my 20s and scraping by on a junior reporter’s salary, I had some sense for the financial stress suffered by everyday Americans. But after a handful of years of diligently saving, I was able to escape those daily worries. Many Americans, alas, never do.

This was hammered home when I recently took the financial well-being questionnaire offered by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). It involves answering 10 questions—things like whether you can handle a major unexpected expense, whether your finances control your life and whether giving a birthday or wedding gift puts a strain on your finances for the month.

I scored an 86, which is the highest possible score for my age group when the questionnaire is self-administered. I don’t tell you this to brag. Take the questionnaire yourself and you’ll realize it isn’t exactly difficult to earn a high score. Most HumbleDollar readers, I suspect, will notch around 70 or higher.

And yet the average U.S. score is just 54. Indeed, a third of the population scores 50 or below—a level “associated with both a high probability (well above 50%) of struggling to make ends meet and of experiencing material hardship,” says a 2017 CFPB report.

The CFPB considers a “very high” score to be 68 and above. What are the attributes of this group? A 2019 CFPB report says 69% make automated deposits into a savings or retirement account, most have health insurance and 80% have $10,000 or more in “liquid savings,” meaning money held as cash or in checking and savings accounts.

What about those at the other end, who notch a “very low” score of 29 and below? Just 5% of these folks are confident they could come up with $2,000 for a financial emergency, 82% can’t always afford the food they need and 96% find it somewhat or very difficult to make ends meet.

Scores tend to be higher among those with more formal education, homeowners, the higher paid, those who are married or living with a partner, folks who have a job with employee benefits, those who are older, and people with stable incomes. Meanwhile, scores are lower among the sick, disabled and unemployed.

But here’s a modest surprise—at least in terms of its impact on financial well-being: Those with less than $250 in liquid savings had an average financial well-being score of 41, versus 68 for those with $75,000 or more. That point difference was “the largest difference observed across any factor examined,” says the 2017 report. It seems significantly boosting financial happiness could be as simple as keeping perhaps $5,000 in the bank.

The CFPB and others have suggested that, while financial well-being is higher among the more affluent, it can also be helped by financial education. As the editor of a financial website, I’d like to think that’s true. But I’m not convinced.

That brings me to a 2014 academic study that looked at financial education, drawing on the results from 201 prior studies. It found that the impact of educational efforts on financial behavior was negligible, especially if that financial education happened more than 20 months earlier. Indeed, the authors suggest that the only strategy with a fighting chance is just-in-time education—where you help folks just before, say, they take out a mortgage or put together a portfolio.

That doesn’t mean financial education is a total waste. A minority of folks will benefit enormously, but they’re the folks who are naturally inclined to save money, plan for the future and so on. In other words, when the financial educators preach, typically the only folks listening are those inclined to be converted. This, I fear, is what I’ve spent my entire career doing—preaching to the converted.

That’s where you, dear reader, come in. In all likelihood, not all of your colleagues, friends and family members are innately sensible about money. My hope: You will keep your ears open, so you know when they’re about to make major money decisions—and you’ll take that as your cue to deliver some just-in-time financial education.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE the six other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

First, do no harm: John Lim lists 12 deadly sins that every investor should strive to avoid.

Should you give up on the tried-and-true mix of 40% government bonds and 60% stocks because bond yields are so low? No way, says Adam Grossman.

“I have a relative who stayed at a $500-a-night hotel,” recalls Rand Spero. “He emailed me to bring him water when I visited, because the hotel charges $5 per bottle.”

When Mike Zaccardi was born, his parents bought him a series EE savings bond. Things would have turned out so much better with stocks. Or would they?

John Yeigh has a financial to-do list for 2020: Get rid of high-cost funds, look to reduce stock exposure, eliminate half-a-dozen expenses and more.

Are you getting the most out of your employer’s 401(k) plan? Maybe it’s time to check everything’s on track for 2020, says Rick Connor.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Opening the Spigot, Humble Bragging and He Can Be Taught

. Jonathan’s

latest books: From Here to Financial Happiness and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Opening the Spigot, Humble Bragging and He Can Be Taught

. Jonathan’s

latest books: From Here to Financial Happiness and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept donations, run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Just in Time appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 17, 2020

Our To-Do List

I HAVE NEVER broken a New Year’s resolution—because, until this year, I’ve never made one. But now that I’m retired, with time on my hands, I figure my wife and I ought to challenge ourselves with 10 financial resolutions for 2020:

We’ll continually monitor routine spending with the goal of reducing or eliminating at least half-a-dozen expenses this year. That’s one every two months. Phone companies, internet providers and insurers, be warned: Here we come. We already have the first expense reduction in the bag. We finally decided to eliminate the daily newspaper. We increasingly read the news online, so we’re probably a few years late to this particular party.

Given today’s euphoric stock market, we’ll reconsider our portfolio weightings and perhaps rebalance our stock-heavy position. A pundit saying “back up the truck” and “there is no risk” makes me wonder whether markets might be close to a top.

We will update our wills. They were written when our adult children were kids. We no longer need to name guardians. Separately, our payable-on-death accounts and tax-deferred accounts could be better organized. If you haven’t updated your will in five or 10 years, it’s probably due for an update.

I’ll consider the impact of the SECURE Act, including the increase in the starting age for required minimum distributions (RMDs) from age 70½ to 72 and the end of the so-called stretch IRA, replaced by the need for most beneficiaries to empty inherited retirement accounts within 10 years. One implication: We’ll now have 18 more months to convert traditional IRAs to Roths before our taxable income gets a boost from RMDs.

My wife and I will revisit our decision to delay claiming Social Security. Perhaps as a halfway measure, we’ll start one of the two payments.

Although we’re fairly apolitical, we will follow 2020’s political developments closely. If one of the more business-unfriendly candidates gains traction, we’ll again consider reducing our overweight position in stocks.

We both turn age 65 in 2020, so we’ll need to sign up for Medicare well ahead of our birthdays. We have our adult children on our supplemental health insurance, so we’ll need to figure out what to do with that coverage.

We still have several small positions in relatively high-cost mutual funds held in tax-deferred accounts. We’re committed to getting rid of these funds, despite the annoying administrative headaches.

I vow to spend more time educating my two children, ages 19 and 25, on financial issues. Happily, they already appear to be climbing the financial knowledge ladder. Now, if I could just get them to read HumbleDollar every day.

Although we’re conservative, buy-and-hold investors who are mainly invested in index funds, I still follow the markets daily. Since I don’t trade frequently, watching makes no difference. My final resolution: Ignore the markets at least one day a week.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. His previous articles include Death and Taxes, Take a Break and 7,000 Days.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. His previous articles include Death and Taxes, Take a Break and 7,000 Days.

Do you enjoy articles by John and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Our To-Do List appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 16, 2020

Magnitude Matters

WHY DON’T WE spend our time and energy on financial issues that have the greatest impact? We’ll drive to a more distant gas station to save 10 cents a gallon, but fail to do all the maintenance needed to extend the life of our car. What lies behind this sort of behavior? The savings from getting the best price per gallon is concrete and immediate, while maintaining our car is long term and abstract. It’s simply easier to focus on the 10 cents.

I have a relative who stayed at a $500-a-night luxury hotel in downtown Boston. He emailed me to bring him water when I visited, because the hotel charges $5 per bottle. Yes, the hotel is pushing the envelope with its water bottle charge, but my relative claiming he won’t pay “on principle” seems like a stretch. Such “injustices” occur when we have concrete price expectations, while we happily tolerate other, much higher costs.

Deciding on a college is a huge investment of time and money. Yet as my family dashed from one campus visit to the next, I wondered if we were being good consumers. Were we prioritizing colleges based on which tour guide captured the interest of our daughter? Perhaps we needed to slow down and do more extensive research. When my daughter decided to apply early decision to a nearby university, we suggested she visit the school a second time. She spent a full day talking to students and sitting in on classes, and came back enthused. It proved to be a good fit.

The importance of considering the financial magnitude of a decision became apparent when I went house shopping with a friend. He was moving into town for work and wanted to get settled quickly. As we raced between showings, one desirable property stood out. There was a crowd at the open house and the broker indicated it would move fast. All bids would be accepted by Sunday evening and the winner would be announced the next day. My friend got caught up in the frenzy and wanted to know what bid might be needed “to win it.”

It struck me as amusing that we had spent just 45 minutes looking at the desired house for sale. I asked my friend how much time he would spend looking at a high-priced sweater. He proudly indicated that he was a bargain shopper. My friend added that, if he were going to pay a lot for an item of clothing, it had better be worth it. Yet soon he could be obligated to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars for a house, initiating this decision after spending less than an hour.

Want to make better purchasing decisions? Try asking these five questions:

What dollar amount are you actually spending or saving?

Are you sidetracked by focusing on low-cost items that are more easily understood?

Do you cite “principle” to defend fretting over small expenditures?

On big ticket items, have you established clear criteria before purchasing?

Have you allocated time and energy that’s appropriate, given the financial magnitude of a decision?

Rand Spero is president of Street Smart Financial, a fee-only financial planning firm in Lexington, Massachusetts. His previous articles include Bearing Gifts, Admission of Guilt and Life Support. Rand

has taught personal finance and strategic planning at the Tufts University Osher Institute, Northeastern University’s Graduate School of Management and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Rand Spero is president of Street Smart Financial, a fee-only financial planning firm in Lexington, Massachusetts. His previous articles include Bearing Gifts, Admission of Guilt and Life Support. Rand

has taught personal finance and strategic planning at the Tufts University Osher Institute, Northeastern University’s Graduate School of Management and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Do you enjoy articles by Rand and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Magnitude Matters appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 15, 2020

12 Investment Sins

WANT TO IMPROVE your investment results? The deadly sins below are not only among the most serious financial transgressions, but also they’re among the most common. I firmly believe that, if you eradicate these 12 sins from your financial life, you’ll have a better-performing portfolio.

1. Pride: Thinking you can beat the market by picking individual stocks, selecting actively managed funds or timing the market.

Antidote: Humility. By humbly accepting “average” returns through low-cost index funds, you will—paradoxically—outperform the majority of investors.

2. Greed: Having an overly aggressive asset allocation.

Antidote: Moderation. Follow the great Benjamin Graham’s advice and keep no more than 75% of your portfolio in stocks. Once you determine your asset allocation, doggedly maintain it through thick and thin by rebalancing periodically.

3. Lust: Being addicted to financial pornography. Financial pornography—think CNBC and Fox Business—may be entertaining, but it has no lasting value and is actually harmful to your financial health by promoting short-termism.

Antidote: Turn off financial media and delete financial apps from your smartphone.

4. Envy: Chasing performance. This sin trips up more investors than any other. It ultimately leads to the cardinal sin of “buying high and selling low.”

Antidote: Stop comparing your investment performance to that of others. Success is not measured by relative performance, but by whether you meet your own financial goals.

5. Gluttony: Failing to save. You may be a financial saint in every other respect, but—if you fail to save—it’s game over. You can’t invest what you haven’t saved.

Antidote: Start saving something today. Slowly raise your savings rate over time.

6. Impatience: Lacking investing stamina has dire consequences. Patience in financial markets is measured in years, sometimes decades. The first decade of the 21st century was not kind to U.S. stock investors, who lost a cumulative 9%. If you had bailed on U.S. stocks in 2009, you would have missed out on the following decade’s glorious rebound, with annualized returns of over 16%.

Antidote: Patience and a knowledge of financial history. While history doesn’t necessarily repeat, it does rhyme. What history has shown time and again is that markets mean revert—that is, sharp declines are typically followed by rebounds.

7. Sloth: Not contributing enough to get your employer’s full 401(k) match. This is like walking past $100 bills on the sidewalk and being too lazy to pick them up. Similarly, make the effort to rebalance. While doing less is generally beneficial when investing, failing to rebalance is the exception to the rule.

Antidote: If you’re too lazy to rebalance, sign up for a low-cost target-date fund, which will rebalance for you. The antidote for not getting your 401(k) match? Just do it.

8. Fear: Having an overly cautious asset allocation. This investing sin is easy to overlook, because inflation is so insidious. Inflation reduces our money’s purchasing power by some 2% to 3% a year. Hiding out in cash investments guarantees you an inflation-adjusted loss of 1% to 2% annually.

Antidote: Overcome your fear of stocks by understanding their historical returns. History suggests that, while there’s a 46% chance that the S&P 500 will be down on any given day and a 27% chance you’ll lose money in any given year, the odds of losing fall to 5% over 10-year stretches and 0% over 20-year holding periods.

9. Imprudence: Failing to diversify. This is a surefire road to the poorhouse. Consider the lesson of the Japanese stock market. The Nikkei 225—analogous to our S&P 500—reached an all-time high of 38,915 in December 1989, before ultimately declining 82% to close at 7,055 on March 10, 2009. Even today, the Nikkei 225 remains about 40% below the peak reached 30 years ago. This should give serious pause to those who advocate investing in a single national market.

Antidote: Diversify, diversify, diversify—by owning both stocks and bonds, by owning thousands of securities through index funds, and by funding traditional retirement accounts, Roth accounts and regular taxable accounts.

10. Negligence: Mixing investing and insurance through variable annuities, equity-indexed annuities and cash-value life insurance. Ever read the entire prospectus for an annuity? I didn’t think so.

Antidote: Keep your investments and insurance separate, with one notable exception: immediate fixed annuities.

11. Hyperactivity: Being an overly active investor. It may seem counterintuitive. But when it comes to investing, it pays to just sit on your hands most of the time. Aside from choosing an asset allocation and rebalancing periodically, further efforts are generally counterproductive.

Antidote: Learn to do nothing, aside from rebalancing once a year or so.

12. Aimlessness: Failing to plan for retirement, including drawing up an investment policy statement. An investment policy statement—a set of ground rules for your portfolio—provides the guardrails against the numerous behavioral pitfalls that investors face. This is probably one of the most overlooked facets of investment planning.

Antidote: Don’t delay another day. Have a retirement plan in place, including a written investment policy statement. Review these documents every year.

John Lim is a physician and author of How to Raise Your Child’s Financial IQ, which is available as both a free PDF and a Kindle edition. His previous articles include How Low? Too Low, Solomon on Money and Out on a Lim

. Follow John on Twitter

@JohnTLim

.

John Lim is a physician and author of How to Raise Your Child’s Financial IQ, which is available as both a free PDF and a Kindle edition. His previous articles include How Low? Too Low, Solomon on Money and Out on a Lim

. Follow John on Twitter

@JohnTLim

.

Do you enjoy reading articles by John and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post 12 Investment Sins appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 14, 2020

Read the Fine Print

IT���S THAT TIME of the year���when we should all reevaluate how much we���re saving in our employer’s 401(k). The 2020 contribution limit is $19,500, up $500 from 2019���s level. For those age 50 and older, the catchup contribution was also raised by $500, to $6,500, so these folks can invest as much as $26,000 in 2020.

In addition, it���s a good time to check we���re getting the most out of our 401(k). What are the rules on the employer match? Are we leaving any of that ���free money��� on the table? How about the plan���s investment options? Are we happy with our choices? Does the recent runup in stocks mean we need to rebalance our mix of stocks, bonds and cash investments?

If your spouse also has a 401(k), you might look at both plans in concert���as well as any other investments���and make decisions to get the best out of each plan. For instance, there were many years when my plan���s investment options were superior to those in my wife���s plan, so we skewed her contributions toward her plan���s better options and I then adjusted my holdings to round out our family���s portfolio. Some of our retirement and taxable accounts might appear stock- or bond-heavy, but at the aggregate level we���re comfortable with our allocation.

In doing your New Year���s 401(k) evaluation, be sure you understand any nuances that could cost you money. I ran into this when my employer sold my division to a private equity firm. Over the next several years, our benefits changed somewhat, but not too dramatically. There was, however, a subtle change to our 401(k) plan that took a few years to come to light and caused a lot of heartache for the employees that were affected.

The situation had to do with ���super savers������employees who save the maximum annual amount allowed in their 401(k) in less than 12 months. Our company provided a 50% match on the first 8% of compensation. The company contributed its matching amount each pay period that the employee contributed. The issue: If an employee hit the maximum contribution prior to year-end and had to stop contributing, the company would also stop contributing its match.

Let���s say an employee was under age 50, earned $240,000 a year and elected to have 25% of her salary deferred. She would have contributed the maximum $19,500 by the end of April, giving her a match of $3,200. By contrast, if she���d spread out her contributions throughout the calendar year, she would have got a match of $9,600.

To prevent this inequity, some plans have a ���true-up��� feature to help you get the maximum match. The employer looks at your account at year-end to determine if the average percentage you contributed would have resulted in a larger match. If so, it makes a true-up contribution.

It turns out that our old company had the true-up feature. But when we were sold and moved to a new benefits platform, the feature disappeared. This happened even though we used the same company to administer the 401(k) and the plan was virtually identical in every other respect. It took several years for an employee to notice the discrepancy. The company eventually revised the plan, but a handful of employees missed out on some of their employer match for a few years.

The moral of the story: Periodically review your accounts and make sure what you expect to happen is indeed happening. If something doesn���t make sense, check with your plan provider or your benefits department. A few minutes on the phone could save you a lot of heartache���and a lot of money.

Richard Connor is��

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Return on Investment, Decision 2020��and��Our Charity. Follow Rick on Twitter��@RConnor609.

Richard Connor is��

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Return on Investment, Decision 2020��and��Our Charity. Follow Rick on Twitter��@RConnor609.

Do you enjoy the articles by Rick and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a�� donation .

The post Read the Fine Print appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 13, 2020

If Only

I TURNED 32 last month. My mother, clearing through clutter as she and my father look to downsize ahead of retirement, found an old savings bond of mine issued shortly after I was born. It���s a series EE bond that cost a modest $25 in December 1987. The finance professor in me reacted with ���imagine if that were invested in the S&P 500.���

The $25 savings bond had grown to $104, a 4.1% nominal annual return and 1.9% after figuring in inflation. Not bad, I guess. It being a 30-year savings bond means the window during which interest is earned has ended, so it���s in my best interest to cash in the bond.

I teach portfolio management at the University of North Florida and I shared this story with my students. I also shared with them what the investment could have been worth.

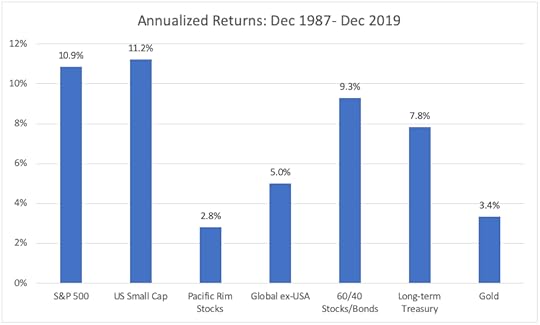

I bet you���re guessing it would be a tidy sum if it had been invested in an S&P 500 index fund, and you���d be right���$686 to be precise, according to PortfolioVisualizer.com. Why wasn���t I consulted? Well, I was just five days old. Had it been put to work in a more aggressive manner, such as a U.S. small-cap fund, the ending value would be a whopping $763.

There is a dark side, though. My lifetime has seen a stellar run for U.S. stocks versus other areas of the world, as I���m sure nearly all readers are aware. The Japanese stock market accounted for nearly half of the global market at its peak in 1989. Surely an investor would have been tempted to play that market given its hot streak, especially as we���re all subject to recency bias. What if my parents had rolled the dice with Pacific Rim stocks? The not-so-tidy sum would have grown to just $61 by 2020, not even keeping pace with U.S. inflation.

There is a dark side, though. My lifetime has seen a stellar run for U.S. stocks versus other areas of the world, as I���m sure nearly all readers are aware. The Japanese stock market accounted for nearly half of the global market at its peak in 1989. Surely an investor would have been tempted to play that market given its hot streak, especially as we���re all subject to recency bias. What if my parents had rolled the dice with Pacific Rim stocks? The not-so-tidy sum would have grown to just $61 by 2020, not even keeping pace with U.S. inflation.

But let���s say the investor thought more globally and invested in MSCI���s All-Country World ex-USA index. Non-U.S. stocks have greatly underperformed the U.S. since the late 1980s, so the same $25 would now be worth just $120 had it been invested���at no cost���in a non-U.S. stock index.

What if the investor were a bit more cautious, and desired to hold a significant bond allocation? A portfolio of 60% U.S. stocks and 40% U.S. bonds with annual rebalancing would have yielded a value today of $429, equal to a 9.3% annual return, with fairly low volatility. Two other possibilities: A gold investment would have produced a value of $72, while a long-term U.S. bond investment would now be worth $282.

Here���s the point that I tried to convey to my students: As wealth grows, diversification���and rebalancing���are critical. Don���t get caught up in the herd mentality and invest in what���s being talked about, such as Japanese stocks in the late 1980s or gold in the current century���s first decade. Instead, draw up your own investment policy statement and have a plan to build wealth over time, while still being flexible to whatever life throws at you. Easier said than done, of course.

Here���s the point that I tried to convey to my students: As wealth grows, diversification���and rebalancing���are critical. Don���t get caught up in the herd mentality and invest in what���s being talked about, such as Japanese stocks in the late 1980s or gold in the current century���s first decade. Instead, draw up your own investment policy statement and have a plan to build wealth over time, while still being flexible to whatever life throws at you. Easier said than done, of course.

Even the most sophisticated and successful savers and investors have regrets about decisions decades ago that cost them dearly in today���s dollars. But we can���t look at life that way. All we can do is learn from our past decisions and then make our best judgment today.

But pardon me, I���ve got to go. It���s time to visit a brick-and-mortar bank for the first time in a few years���so I can cash in my EE bond.

Mike Zaccardi is a portfolio manager at an energy trading firm and a finance instructor at the University of North Florida.

He also works as a consultant to financial advisors on an hourly basis, helping with portfolio analysis and financial planning. Mike is a Chartered Financial Analyst and Chartered Market Technician, and has passed the coursework for the Certified Financial Planner program. Follow Mike on Twitter

@MikeZaccardi

, connect with him via

LinkedIn

or email him at

MikeCZaccardi@gmail.com

.

Mike Zaccardi is a portfolio manager at an energy trading firm and a finance instructor at the University of North Florida.

He also works as a consultant to financial advisors on an hourly basis, helping with portfolio analysis and financial planning. Mike is a Chartered Financial Analyst and Chartered Market Technician, and has passed the coursework for the Certified Financial Planner program. Follow Mike on Twitter

@MikeZaccardi

, connect with him via

LinkedIn

or email him at

MikeCZaccardi@gmail.com

.

Do you enjoy the articles by Mike and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a�� donation .

The post If Only appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 12, 2020

Cut the Bonds?

JUST BEFORE Thanksgiving, something odd happened on Wall Street. Three of the major brokerage firms��issued remarkably similar��reports declaring the death of the ���60/40��� approach to investing. What exactly does this mean���and should you be concerned?

By way of background, 60/40 refers to a traditional and very common strategy for building portfolios: 60% stocks and 40% bonds. Historically, most university endowments, as well as many individuals, have chosen this mix of investments because it offers a reasonable balance, with growth coming from the stocks and stability from the bonds.

The approach has worked extraordinarily well. Over the past 95 years, a simple 60/40 mix of U.S. stocks and bonds has returned an average of nearly 9% a year. More important, it���s been very effective at reducing risk. In 2008, for instance, when the stock market declined 37%, a 60/40 portfolio would have dropped just 17%. This wasn���t an isolated case. The 60/40 approach has come through for investors in other times of economic stress, including the Great Depression.

So why is the 60/40 approach suddenly under attack? In my view, this stems from the dramatic growth of index funds. In recent years,��investors have been fleeing��actively managed funds���that is, funds run by traditional stock-pickers���and opting for passively managed funds. The fund performance data��indicate this embrace of indexing is a smart move���and not just for ordinary investors. A simple 60/40 mix of stock and bond index funds has delivered��better results��than most university endowments, including Ivy League schools.

For many years, it���s been awfully hard for anyone to top the humble 60/40 mix, especially when it���s implemented with a set of low-cost index funds. But this trend doesn���t serve the interests of Wall Street brokers. Because index funds pursue a largely buy-and-hold strategy, they don���t generate nearly the volume of trading commissions that active strategies do���and hence it���s no great surprise to see Wall Street analysts taking aim at the tried-and-true 60/40. They would like nothing better than to shake investors loose from these simple investments.

I don���t want to dismiss these analysts out of hand, just because they might be biased. It���s important to understand their arguments. While each of the brokers��� views varied, they all focused on the same key concern: Bonds, they argued, are expensive. One broker went as far as to say they���re in a bubble. But this is where their arguments get shaky.

There���s no question that bonds are expensive. Yields on U.S. Treasurys are just 1.5% to 2.3%. The question is, how best to respond? The brokers��� prescription was to move money out of government bonds, and instead buy corporate bonds and emerging markets bonds���investments that carry far more risk. They also recommend that investors buy more stocks as an alternative to bonds, favoring companies that pay larger dividends.

This is a dangerous argument. No matter how you look at it, the diversification benefit of government bonds has been strong in virtually every time period. The analysts argue that this benefit could break down. But if you look at historical data, it���s hard to make that case. More important, government bonds offer investors a guarantee that stocks never will: that folks will receive their principal back. I see it as extremely unhelpful to suggest that investors move out of government bonds, and into stocks or into riskier bonds.

That said, there���s nothing magical about the specific percentages in the 60/40 mix. What���s important is to build a portfolio of stocks and bonds that���s the best fit��for you. That means a portfolio that accounts for your household���s financial goals, as well as your objective capacity to take risk and your personal tolerance for risk.

That might end up being 60/40, but it might just as easily be 40/60, 80/20 or some other combination. What���s universal, however, is the importance of keeping things simple and maintaining a mix of stocks and government bonds. As much as Wall Street would prefer that you opt for something more exotic���and more lucrative for them���I would resist the temptation.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Got You Covered,��An Unkind Act��and��The REIT Stuff

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Got You Covered,��An Unkind Act��and��The REIT Stuff

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy articles by Adam and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a�� donation .

The post Cut the Bonds? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 11, 2020

Opening the Spigot

BEEN A DILIGENT saver during your working years? Upon retirement, you���ll likely find it tough to transform yourself into a happy spender. This is not a problem you���ll read much about���because it isn���t exactly a widespread affliction.

The fact is, most folks struggle their entire life to control their spending, only to reach retirement with too little saved. At that point, they have no choice but to tighten their belt. Indeed, the statistics are alarming. For 50% of couples and 70% of single individuals, Social Security accounts for at least half of their retirement income. If you exclude the value of Social Security and pensions���but count real estate���the typical household approaching retirement age has a net worth of just $175,000.

But what if you���re among the minority, those avid savers who reach retirement in good financial shape? This is the moment to reap your reward. But if you���re like many HumbleDollar readers, you���ll find it hard to flip the switch from saving to spending. What to do? Here are five thoughts:

1. Just Say No. If you���ve always thought folks were idiots for lavishing money on spanking new European luxury sedans, you shouldn���t buy one just because you retire with a plump nest egg. In all likelihood, it would be a deeply uncomfortable experience, you���d suffer terrible buyer���s remorse���and you���d think less about the marvels of German engineering and more about your emptier bank account.

The fact is, money can buy many things, but perhaps the important thing it can buy is a sense of financial security. Retirement often brings a heap of anxiety. Not only are we giving up our paycheck, but also there���s a slew of risks to worry about. Among them: We might outlive our money, get hit with a big bear market right after we retire, incur steep long-term-care costs, and suffer high inflation��or��low average investment returns��throughout retirement.

A fat nest egg can ease these worries. There���s great pleasure in knowing we never again need worry about money, though occasional anxious moments are pretty much unavoidable.

That brings me to an important distinction: You might choose not to spend, because not spending delivers greater happiness than spending. But if you���re choosing not to spend out of fear, you should probably seek out a social worker or a psychologist, so you can better understand what lies behind your anxiety. Each of us gets to travel this road just once, and you don���t want to reach the end of the journey filled with regrets.

2. Ponder Your Passions. We spend decades preparing financially for retirement and yet we often give scant thought to what we���ll do with all that free time. Approaching retirement? Start thinking.

Retirement is a chance to devote our days to work we���re passionate about, without worrying about whether that work comes with a paycheck. If we can figure out what we really care about���for some it will be easy, for others it may take trial and error���retirement has the potential to be the most fulfilling time in our life.

Maybe pursing our passions will cost very little. Maybe it���ll cost a lot. But either way, if we are passionate about what we���re doing, we���ll likely have few qualms about the price tag involved.

3. Head Games. Experts often recommend that retirees use a 4% annual withdrawal rate. A popular strategy: Each year, we should sell the prescribed amount from either our stocks or our bonds���depending on which has lately performed best���and then direct the proceeds to a cash account that���s used to cover spending in the years ahead. Problem is, this strategy can create anxiety, because we���re constantly pondering how much our portfolio is worth and what we ought to sell, and that can deter folks from spending.

What���s the alternative? You might minimize the handwringing by taking an old school approach���and declaring some money fair game for spending and other money off-limits. For instance, you might give yourself permission to spend your Social Security benefit and all of your portfolio���s dividends, interest earnings and mutual fund distributions, while keeping your fears at bay by never selling any securities. What if that doesn���t give you enough income? You might bite the bullet, buy an immediate fixed annuity and then allow yourself to spend those monthly checks.

There���s nothing novel about this advice. Folks have long allowed themselves to ���spend income, but never dip into capital.��� Experts often pooh-pooh such an approach as sub-optimal. But guess what? It may not be a strategy favored by economists, but it works for humans.

4. Foot the Bill. If you balk at spending money on yourself, consider spending it on others. Think of it as a chance to exploit three of the great insights from happiness research���that spending on others often delivers greater happiness than spending on ourselves, that experiences bring greater happiness than possessions, and that friends and family are a huge source of happiness. Indeed, the reason experiences can be so fun is because they���re typically enjoyed with others.

Some possibilities: Foot the bill for the family reunion, take a trip to visit the grandkids, pick up the tab when you���re out with friends or pay to take the entire family on vacation. Also consider the charities you want to support. All this may take some experimentation, as you figure out how much money you���re willing to part with, without leaving yourself feeling uneasy.

5. Prepare Your Heirs. If you���re reluctant to spend your own money, soon enough your heirs or a charity will get their chance. Will they handle your money with care? This is the moment to find out.

You might identify some charities that you find meaningful and start monitoring them, paying close attention to how much of the money they raise ends up with the folks they���re trying to help. Ideally, administrative costs and fundraising should consume less than 10 cents out of every $1 raised.

Meanwhile, with your heirs, you could take advantage of the annual gift-tax exclusion, and give up to $15,000 to your children and other family members you���re looking to help. Then check to see how the money is used. Does it end up paying down debt, padding an investment account or funding education���or does it lead to fancier vacations and more lavish cars?

If you���re worried about how your intended heirs will use the money you bequeath, you could explore some sort of trust arrangement that disburses money over time or for specific purposes. But think long and hard before going this route: Trusts often prove to be excellent vehicles for transferring wealth to money management companies and trust administrators.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Humble Bragging,��He Can Be Taught,��Hits 2017-19��and��Just Do It

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Humble Bragging,��He Can Be Taught,��Hits 2017-19��and��Just Do It

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Opening the Spigot appeared first on HumbleDollar.