Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 337

February 9, 2020

Believe It or Not

TESLA FOUNDER Elon Musk is, to me, the ultimate investment Rorschach test. To his supporters, Musk is a genius without equal. As one Wall Street analyst put it, “If Thomas Edison and Henry Ford made a baby, that baby would be called Elon Musk.” But to his detractors, Musk is an erratic individual and the leader of a money-losing company whose bravado has landed him in hot water with the SEC.

Last week, Tesla’s stock encapsulated those contrasting views. On Monday and Tuesday, the stock gained 36%. But then, on Wednesday, it dropped back 17%. To put that in context, on a typical day, the overall stock market moves about 1%.

These extreme movements are an example of what economist Robert Shiller, in his new book, calls “narrative economics”—a story so compelling that it begins to dominate conversation, spread rapidly and take over headlines. In modern parlance, the story goes viral.

While Tesla is notable, these kinds of narratives have driven countless booms and busts—from Dutch tulips to the dot-coms to bitcoin and now Tesla. In each case, the narratives combine a little bit of data with a little bit of imagination to paint a picture that drives investors—or, to be more accurate, speculators—into a frenzy.

Sometimes narratives come from hucksters and promoters, but sometimes they come from reliable sources, and that can propel them even faster. In 2004, Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the Federal Reserve, made a statement that helped stoke enthusiasm for the housing market. You know how that story ended.

But here’s the problem with stories: They’re not all bad. Stories can help us understand and make sense of the world. In fact, memory experts will tell you that stories help us retain information in a way that’s impossible with raw facts and figures. That’s how people accomplish feats like reciting 100,000 digits of pi. Stories do serve a purpose.

As an investor, how can you tell the difference between a narrative that’s worth your attention and one that’s likely to lead you astray? Below are five questions to ask:

1. Does it sound too glib? The best stories—the ones that people most like hearing and repeating—are the ones that sound clever and unique. During the dot-com era, people talked about the “new economy.” During the 2008 financial crisis, people talked about the “new normal.” When you hear things like that, it’s a sign you’ll want to dig deeper.

2. What does the data say? If someone is telling you a story, always start by asking for evidence. Then seek out your own data—from unbiased sources. If it’s a financial topic, I recommend the St. Louis Fed or the Congressional Budget Office.

3. What’s the other side of the argument? Tesla’s detractors like to say that the company has never had a profitable year. That’s true, but what they won’t tell you is that recent quarters have indeed been profitable, suggesting that things might be heading in the right direction. With the internet, it usually isn’t hard to find opposing points of view. Seek them out and use them to form your own judgment.

4. What are the historical analogs? This week, someone asked me, “How worried should people be about the coronavirus?” My recommendation, as a starting point, was to compare this outbreak to prior ones, such as the Ebola outbreak five years ago. While every story is unique, they usually have a historical analog that’s useful for comparison.

5. What if there is no historical analog? On my bookshelf, one volume sits front and center: The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. In it, Taleb describes how Europeans always assumed that all swans were white—until they traveled to Australia and learned that black swans also exist.

The lesson: Just because something hasn’t happened before, or just because you aren’t aware of it, doesn’t mean that it can’t happen. There’s a first time for everything. So look for historical analogs—but, if you can’t find one, don’t dismiss it. Instead, ask if you might have a black swan on your hands. That’s my framework for evaluating narratives.

What should you do if you see something that could be a home run or could just as easily be a flop? That’s when I employ my $1,000 rule. If, early on, you had put just $1,000 into Tesla or bitcoin, or into Apple before Steve Jobs came back, you’d be sitting on a fortune today, even if you had also wagered $1,000 on some duds. If the fear of missing out is too strong to suppress, here’s my recommendation: Risk just a small amount, view it like a lottery ticket, definitely don’t buy too many—and hope for the best.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Portfolio Makeover, The Wager Revisited and Seven Paradoxes

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Portfolio Makeover, The Wager Revisited and Seven Paradoxes

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Believe It or Not appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 8, 2020

Nobody Told Me

I HAVE DEVOTED my entire adult life to learning about money. That might sound like cruel-and-unusual punishment, but I’ve mostly enjoyed it. For more than three decades, I’ve spent my days perusing the business pages, reading finance books, scanning academic studies and talking to countless folks about their finances.

Yet, despite this intense financial education, it took me a decade or more to learn many of life’s most important money lessons and, indeed, some key insights have only come to me in recent years. Here are 10 things I wish I’d been told in my 20s—or told more loudly, so I actually listened:

1. A small home is the key to a big portfolio. My first wife and I bought a modest house, because we worried that we couldn’t really afford anything bigger. I ended up living in that house for two decades.

Financially, it turned out to be one of the smartest things I’ve ever done, because it allowed me to save great gobs of money. That’s clear to me in retrospect. But I wish I’d known it was a smart move at the time, because I wouldn’t have wasted so many hours wondering whether I should have bought a larger place.

2. Debts are negative bonds. From my first month as a homeowner, I sent in extra money with my mortgage payment, so I could pay off the loan more quickly. But it was only later that I came to view my mortgage as a negative bond—one that was costing me dearly. Indeed, paying off debt almost always garners a higher after-tax return than you can earn by investing in high-quality bonds.

3. Watching the market and your portfolio doesn’t improve performance. This has been another huge time waster. It’s a bad habit I’m belatedly trying to break.

4. Thirty years from now, you’ll wish you’d invested more in stocks. Yes, over five or even 10 years, there’s some chance you’ll lose money in the stock market. But over 30 years? It’s highly likely you’ll notch handsome gains, especially if you’re broadly diversified and regularly adding new money to your portfolio in good times and bad.

Over the past decade, I’ve upped the bond position in my portfolio, so today—at age 57—I’m at 60% stocks and 40% interest-generating investments. (The latter includes the private mortgage I wrote for my daughter.) But long before then, I spent an awful lot of time debating whether to invest more in bonds. It simply wasn’t necessary.

5. Nobody knows squat about short-term investment performance. This is closely related to point No. 4. One of the downsides of following the financial news—or, worse still, working as a columnist at The Wall Street Journal—is that you hear all kinds of smart, articulate experts offering eloquent predictions of plummeting share prices and skyrocketing interest rates that—needless to say—turn out to be hopelessly, pathetically wrong. In my early days as an investor, this was, alas, the sort of garbage that would give me pause.

6. Put retirement first. When I was in my 20s, I remember a financial expert saying that, “If you don’t own a house by age 30, you’ll likely never own one.” I didn’t realize it at the time, but not only was this alarmist nonsense, but also it prioritized the wrong thing.

Buying a house shouldn’t be our top goal. Instead, retirement should be. It’s so expensive to retire that, if you don’t save at least a modest sum in your 20s, the math quickly becomes awfully tough—and you’ll need a huge savings rate to amass the nest egg you need.

7. You’ll end up treasuring almost nothing you buy. Over the years, I’ve had fleeting desires for all kinds of material goods. Sometimes, I caved in and bought. Most of the stuff I purchased has since been thrown away.

Today, I have a handful of paintings and some antique furniture that I prize, and that’s about it. This is an area where millennials seem far wiser than us baby boomers. They’re much more focused on experiences than possessions—a wise use of money, says happiness research.

8. Work is so much more enjoyable when you work for yourself. These days, I earn just a fraction of what I made during my six years on Wall Street, but I’m having so much more fun. No meetings to attend. No employee reviews. No worries about getting to the office on time or leaving too early. I’m working harder today than I ever have. But it doesn’t feel like work—because it’s my choice and it’s work I’m passionate about.

9. Will our future self approve? As we make decisions today, I think this is a hugely powerful question to ask—and yet it’s only in recent years that I’ve learned to ask it.

When we opt not to save today, we’re expecting our future self to make up the shortfall. When we take on debt, we’re expecting our future self to repay the money borrowed. When we buy things today of lasting value, we’re expecting our future self to like what we purchase.

Pondering our future self doesn’t just improve financial decisions. It can also help us to make smarter choices about eating, drinking, exercising and more. Tempted to have one more slice of pizza? Tomorrow’s self would likely prefer you didn’t.

10. Relax, things will work out. As I watch my son, daughter and son-in-law wrestle with early adult life, I glimpse some of the anxiety that I suffered in my 20s and 30s.

When you’re starting out, there’s so much uncertainty— what sort of career you’ll have, how financial markets will perform, what misfortunes will befall you. And there will be misfortunes. I’ve had my fair share.

But if you regularly take the right steps—work hard, save part of every paycheck, resist the siren song of get-rich-quick schemes—good things should happen. It isn’t guaranteed. But it’s highly likely. So, for goodness sake, fret less about the distant future, and focus more on doing the right things each and every day.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE the six other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

“Traditionally, retirement was a 30-year period following a 40-year working career,” notes Robert Lindstrom. “But what if you were able to redistribute some of those 30 years?”

What captured the interest of HumbleDollar’s readers last month? Check out January’s seven most popular articles.

For 35 years, Dennis Friedman lived in a one-bedroom, 789-square-foot condominium. He reaped nine crucial financial benefits.

Is gold an unproductive asset with terrible long-term performance—or a great way to diversify a portfolio? Sanjib Saha wrestles with the question.

It’s been more than three decades since the Japanese stock market hit an all-time high. The extraordinary market carnage holds five key lessons for investors, says John Lim.

Got a portfolio in need of a makeover? Adam Grossman shows you how to get it done—using a four-step process.

This week, we also launched HumbleDollar’s revamped homepage. It now includes a section called “Second Look” that highlights earlier articles that readers might have missed.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Great to Gone, Five Freedoms and Helping Them Along.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Great to Gone, Five Freedoms and Helping Them Along.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Nobody Told Me appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 7, 2020

Got Gold?

YEARS AGO, I spent a few days in Bangkok touring the city. A highlight of my short stopover was the temple of Wat Traimit, which houses a five-and-a-half metric ton Golden Buddha, made of approximately $250 million of gold.

Cast more than 700 years ago, the statue symbolized the prosperity and cultural heritage of Sukhothai, the first Thai kingdom. Sometime in the 18th century, the statue was completely plastered over to conceal its value from Burmese invaders. The significance of the statue was forgotten for some 200 years, until the plaster accidentally chipped off to reveal the gold underneath. The miraculous 1955 discovery made headlines and the statue was restored to its former glory. I was mesmerized by its brilliance and beauty.

Our longing for gold is as old as recorded history. It was significant thousands of years ago, as evidenced by Egyptian archeology. Ancient Greeks, Incans, Aztecs and many other civilizations used gold. It was viewed as a status symbol to separate the elite from the ordinary. Holding gold was synonymous with holding power.

Why such a deep-rooted fascination? There’s no simple answer. The color and luster of the metal create a unique aesthetic appeal. Gold is scarce, yet durable and resilient, hence it’s historical role as a way to store wealth and transfer it to future generations. Even today, in many countries, gold is widely used in social ceremonies and religious offerings. Strong consumer demand persists.

For centuries, gold also played a vital role in monetary systems. The gold standard, a system that promised a fixed gold-based exchange rate for circulating paper currency, was widely used by many countries until World War I. In 1944, gold’s importance was reestablished by the Bretton Woods agreement. This new system pegged all other currencies to the U.S. dollar and allowed them to be converted to physical gold at $35 per ounce. But the new system soon faltered. The international currency-to-gold convertibility was finally abolished almost half-a-century ago by President Nixon.

Nixon’s decision triggered two shifts in the global monetary system. First, the smooth functioning of fiat—or paper—money around the financial world became solely dependent on the responsible, collaborative action of central banks. Second, the price of gold went haywire. It spiked almost 20-fold in less than 10 years, only to lose 60% over the following two decades. The rollercoaster ride continued in the current century. Gold climbed from less than $275 per ounce in 2000 to more than $1,900 in 2011. From there, it dropped below $1,075 in 2016 and then crept up again, closing yesterday at $1,570. Widely differing views on its value have made gold a highly speculative asset.

Meanwhile, many central banks maintain substantial gold reserves. The U.S. leads with over 8,000 metric tons, more than 4% of all gold ever mined. But should people like you and me follow suit and invest in gold? I struggled with this question during my retirement planning—and found no clear answer.

Many experts, including Warren Buffett, shun gold. It’s a nonproductive asset. It neither generates a dividend nor produces anything of value. The 200-year return is terrible. The only way you can make money, after paying the 28% capital gains tax, is by selling to someone who is willing to pay a higher price. Gold’s ability to hedge against short-term inflation is questionable. The list of drawbacks goes on and on.

On the flip side, there are countless pundits who favor gold. The World Gold Council, an organization of 26 goldmining companies from across the globe, presents counterarguments to stimulate demand for gold, promoting it as a strategic investment. Gold’s low correlation with other major asset classes makes it an appealing portfolio diversifier. It’s also a safe haven, preserving financial value over very long periods, and it’s seen as a hedge against unforeseen crises and “black swan” events. For long-term investors, gold is pitched as insurance, rather than as a profit-making investment.

Gold is part of a few well-known model portfolios, especially those designed to weather bad times. The so-called permanent portfolio stashes up to a quarter of total assets in gold. An all-weather portfolio might allocate 7.5%. Both of these portfolios held up well in recent recessions.

Torn between these opposing views, I opted for the middle ground. I decided to buy some and be done with the dilemma. But because of its steep price by historical standards, I limited my gold allocation to 5%—and I hope my portfolio’s performance will never need its help.

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. His previous articles include Risky Option, Thanks for Nothing and Blessing in Disguise. Self-taught in investments, Sanjib passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. He’s passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances.

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. His previous articles include Risky Option, Thanks for Nothing and Blessing in Disguise. Self-taught in investments, Sanjib passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. He’s passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Got Gold? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 6, 2020

Small Is Beautiful

I’M SAYING GOODBYE to an old friend I’ve known for 35 years. We had a special relationship that enriched my life in many ways. Although I’ll be moving to a new city and will never see my old friend again, I’ll always be grateful for our relationship, and how it helped me financially and emotionally.

You see, as I put my dear little friend—a one-bedroom, 789-square-foot condominium—up for sale, I’ve come to realize how important it was to have a home that helped me live below my means.

Our relationship over the years had its ups and downs. It would have been nice to have a larger home, so I could have offered out-of-town friends and family a place to stay. It would also had been more convenient to have a washer and dryer in my home, so I didn’t have to lug my laundry down to the appliances in the garage.

I have to admit that moving to a larger home crossed my mind occasionally. A few years after I bought my condo, I considered purchasing a nearby 2,258-square-foot house with three bedrooms and two bathrooms.

At the time, this single-family home was selling for $275,000, roughly three times more expensive than my condo. That single-family home has appreciated nicely over the years and is now listed at $1.2 million. Instead, I stuck with my condo, for which I paid $90,000 and which was recently appraised at $377,000.

I ask myself, “Would I have been further ahead financially if I’d bought the larger, more expensive home?” It’s difficult to make an accurate assessment without knowing the total cost of owning each property. A bigger house comes with bigger expenses. That’s one reason I didn’t buy the house. When I looked at it, it already needed a new roof. I also didn’t need a house that size.

Indeed, I have no regrets about my small, less expensive condominium. It’s benefited me in at least nine different ways:

The condo meant low fixed expenses, including modest mortgage payments, property taxes, utilities and insurance.

It helped me have hope for the future, because I could save for my long-term goals.

It allowed me to make maximum contributions to my 401(k) plan.

It also allowed me to contribute to a traditional IRA, a Roth IRA and a personal savings account.

It gave me the financial leeway to build up a six-month emergency fund.

It helped me live free from financial stress.

It allowed me to become financially independent, including the freedom to retire at age 58.

It helped me help others. I was able to quit the workforce, so I could assist my parents as a caregiver.

Most important, it put an affordable roof over my head, keeping me safe and secure during difficult economic times.

The important thing to remember when purchasing a home: Buy one that you can afford, so you won’t have to mortgage your financial future. That’s exactly what I did—and I’m thankful for it.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include On My Mind, Turning the Page and Journey’s End. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include On My Mind, Turning the Page and Journey’s End. Follow Dennis on Twitter @DMFrie.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Small Is Beautiful appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 5, 2020

Crash Course

THE JAPANESE just “celebrated” the 30th anniversary of their stock market’s peak. The Nikkei 225 hit an all-time high of 38,916 in December 1989. Today, it stands at 23,085, some 40% below.

“But the Japanese stock market in the 1980s was the mother of all bubbles,” you might respond. Perhaps. But what about the Nasdaq bubble of the late ’90s? True, the Nasdaq Composite Index has finally returned to its 2000 peak. But it took 15 years.

By contrast, it’s been 30 years since Japanese stocks last recorded a new high—close to an investing lifetime. Imagine the pain of a Japanese couple who started investing in 1989 and have yet to make any money after three decades. The Japanese experience may be anomalous. But I believe it can teach us five valuable investing lessons.

1. Geographical diversification is imperative. I disagree with the late Jack Bogle, who didn’t believe that U.S. investors needed to diversify globally: “I don’t quite understand where this thing is that you must have a global portfolio. Maybe it’s right. Of course, maybe anything is right, but I think the argument favors the domestic U.S. portfolio.”

Bogle goes on to mention how the U.S. has so many advantages in terms of entrepreneurial spirit, sound institutions and solid governance. The problem is, many people were also singing Japan’s praises in the 1980s. Markets price in that sort of information. If U.S. companies are felt to be dominant and have intrinsic advantages, that’s already priced into their stocks.

I’m not saying that the U.S. is like Japan. But I also don’t know that what happened to Japanese stocks could never happen here in the U.S. Those who believe otherwise need a dose of humility.

2. Bonds still play a role in portfolios. The great Benjamin Graham warned against having more than 75% of one’s holdings in stocks. While some may consider his advice antiquated, I believe it’s prudent.

If the Japanese experience teaches us anything, it’s that stocks can be incredibly risky. A Japanese investor who had some portion of his or her holdings in bonds fared far better than one fully invested in stocks. If nothing else, it would have allowed him or her to sleep better at night.

Bond yields around the world have never been lower and, indeed, many are negative. This has prompted some to question whether bonds still make sense. The answer is an emphatic yes, but with a key caveat: Since the role of bonds in portfolios is to provide ballast and diversification, “reaching for yield” by taking greater credit and duration risk for incrementally higher returns is probably unwise.

3. Risk tolerance is shaped by our experiences. The average Japanese household stockpiles cash to the tune of over 50% of their financial holdings. This compares to just 14% for U.S. households. While there are probably numerous reasons for Japan’s cash obsession—including cultural reasons, deflation and low financial literacy—the terrible stock market performance of the past three decades is no doubt a major factor.

If we want to be successful investors, we must guard against risk tolerance “drift.” In a protracted bull market, we need to be careful not to allow our risk tolerance to creep higher—and we might even want to ratchet it down a notch. Similarly, we also need to guard against allowing our risk tolerance to plummet during bear markets.

4. Never say never. I believe strongly that, to be a successful investor, we need to know our financial history. In the words of George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” That said, it can also be a mistake to extrapolate history too far.

For example, there has never been a 20-calendar-year period of negative stock market returns for the S&P 500. (Clearly, the same cannot be said for the Japanese stock market.) Could this rule be violated some day? Of course, it could. The question to ask yourself is this: Would my portfolio and the financial future it represents be okay in the event that the next two decades result in zero or negative returns for the U.S. stock market?

5. Mean reversion is real. The stock market wasn’t the only bubble in Japan in the late 1980s. Real estate in Japan also soared. At its peak, it’s estimated that all of the land in Japan—geographically slightly smaller than California—was worth $18 trillion, or almost four times higher than the value of all U.S. real estate at that time. Mean reversion—the tendency for bad times to follow good and vice versa—almost guaranteed that future returns for the Japanese stock and real estate markets would cool from the lofty levels of the late 1980s.

Sophisticated investors can estimate the expected long-term returns embedded in stock prices using the dividend discount model. Applying that model to today’s U.S. stock market is sobering. It implies future returns that are barely above inflation. By contrast, the outlook for international stocks is much brighter. After inflation, emerging markets could deliver an annual, after-inflation return of close to 7%.

The lesson is clear: Trees don’t grow to the sky. It’s a huge mistake in investing to extrapolate the past into the future. In fact, doing the opposite will usually get you closer to the truth.

John Lim is a physician and author of How to Raise Your Child’s Financial IQ, which is available as both a free PDF and a Kindle edition. His previous articles include 12 Financial Sins, 12 Investment Sins and How Low? Too Low

. Follow John on Twitter

@JohnTLim

.

John Lim is a physician and author of How to Raise Your Child’s Financial IQ, which is available as both a free PDF and a Kindle edition. His previous articles include 12 Financial Sins, 12 Investment Sins and How Low? Too Low

. Follow John on Twitter

@JohnTLim

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Crash Course appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 4, 2020

January’s Hits

AT THE BEGINNING of the year, many of us resolve to get our finances in shape, which means January is always a busy month at HumbleDollar. What were folks reading? Here are last month’s seven most popular articles:

First, do no harm: John Lim lists 12 deadly sins that every investor should strive to avoid.

Should you give up on the tried-and-true mix of 40% government bonds and 60% stocks because bond yields are so low? No way, says Adam Grossman.

Why do investors persist in trying to beat the market? Drawing on the work of behavioral finance expert Meir Statman, Robin Powell lists eight key reasons.

When Mike Zaccardi was born, his parents bought him a series EE savings bond. Things would have turned out so much better with stocks. Or would they?

Want to avoid Medicare premium surcharges? James McGlynn discusses IRMAA, the scourge of high-income retirees—and how to keep her at bay.

How many different ways can we mess up financially? To complement his earlier list of investment sins, John Lim offers a dozen personal finance sins that we should all strive to avoid.

“Personal finance is bedeviled by paradoxes, so no individual—no matter how rational—can always make optimal decisions,” argues Adam Grossman, who cites seven conundrums.

Meanwhile, January’s most popular newsletters were Opening the Spigot and Just in Time.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Great to Gone, Five Freedoms and Helping Them Along.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Great to Gone, Five Freedoms and Helping Them Along.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post January’s Hits appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 3, 2020

Trading Time

THERE’S LATELY been much buzz about the FIRE—or financial independence/retire early—movement. The idea is to get yourself to the point where you don’t have to work anymore at a younger age than the traditional retiree.

There’s a wide spectrum of strategies, with a lot of the FIRE community relying on extreme frugality to supersize their savings. Others gun for something called FatFIRE: Think startup company that has a “liquidity event,” which leaves employees with millions in the bank, often at a young age.

I spent most of my 20s pursuing something in the middle. I never intended to retire before age 50, but I certainly didn’t plan on working too long after 50, either. Pursuing this strategy meant saving as much as we could and paying down debt at an aggressive rate. My wife and I both worked, so we were able to do this and still live a fairly nice lifestyle.

Then we had our first child. I now know that children are “budget busters” and that not having kids is a surefire way to boost your free cash flow. The financial impact of having children, however, isn’t the only reason I’m no longer pursuing FIRE. There was also the realization that I have 18 summers with each of my kids before they become independent. This clarified the way I wanted to spend my time. Thus began my transition from FIRE to a concept I’ve dubbed FIRR, which stands for financial independence/redistribute retirement.

Traditionally, retirement was a 30-year period following a 40-year working career. But what if you were able to redistribute some of those 30 years? What if you could pull forward those future activities that you’re excited about and enjoy them now or in the near future? For me, what if I could borrow some time from retirement to spend those 18 summers with my kids?

Perhaps the most obvious way to do this is to take a sabbatical. More and more companies seem to be offering this as a perk. Even more would probably be open to a negotiated sabbatical.

Another strategy would be to negotiate more vacation time. You might ask for this when you take a new job or ask your current employer for more vacation time instead of a raise. You might even “buy” more vacation time by taking a corresponding pay cut.

You’ve heard the cliché that, if you love what you do, you’ll never work a day in your life. Too often, we—and that includes me—persevere in doing things that make us unhappy today, so later we can do things that make us happy. But perhaps you could avoid the unhappiness by redistributing your retirement years by, say, switching careers, or employers, or your current role at the office. I love the question popularized by Tim Ferris: “What would you do if retirement wasn’t an option?”

As the onion layers peel off, you can imagine even more ways to redistribute retirement years. Maybe you don’t need more vacation time or you already have a pretty flexible schedule. But there’s something special, but costly, that you’re hankering to do. Why not skip most retirement savings for one year—though still save enough to get that employer match—and take the trip you’re dreaming of?

Notice that financial independence still comes first, because the financial planner in me still believes the “redistribute retirement” part can only come after you’re at least on track toward financial independence. Choosing to redistribute retirement without being on track would be financially irresponsible.

There are obviously serious career and financial considerations when contemplating many of these strategies. Remember, we’re talking about redistributing retirement, not early retirement. You’ll still have to work the proverbial 40 years, which means you’ll work until a later age. But perhaps the tradeoff would be worth it. That’s the choice I’ve made.

Robert Lindstrom is the founder of

Provision Financial Planning

, a fee-only financial planning firm in Towson, Maryland. He focuses on helping young families and near-retirees plan financially for life’s transitions. Follow Robert on Twitter @RLindstrom7211

.

Robert Lindstrom is the founder of

Provision Financial Planning

, a fee-only financial planning firm in Towson, Maryland. He focuses on helping young families and near-retirees plan financially for life’s transitions. Follow Robert on Twitter @RLindstrom7211

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Trading Time appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 2, 2020

Portfolio Makeover

AT LEAST ONCE a week, I run across the sort of portfolio I like to call a “broker’s special.” While each is different, they typically include some mix of the following:

A handful of mutual funds with names like “New Economy” or “New Discovery” or “New Perspectives.”

Some commodity funds.

10 or 20 individual stocks.

Funds with names heavy on buzzwords such as “infrastructure” and “renewable energy.”

And, in some cases, master limited partnerships, options or other derivatives.

In all, there might be 25, 50 and perhaps more separate holdings. What’s wrong with a portfolio like this? In addition to the obvious drawbacks—unpredictable performance, unnecessary cost and tax-inefficiency—perhaps the biggest issue is that these portfolios are so complicated that it’s virtually impossible for investors to know what they own.

To be sure, account statements will list each holding, but that’s of little help when the list is as long as your arm. Meanwhile, what gets obscured is the most crucial fact: the portfolio’s overall asset allocation—its breakdown between stocks, bonds, cash, commodities and other asset classes.

This is a critical shortcoming because, according to the research, asset allocation is the single biggest driver of a portfolio’s risk level and expected return. If you don’t know your asset allocation, you have no idea whether your finances are walking a high wire or resting on solid ground.

If you feel like your portfolio could benefit from some spring cleaning, I recommend these four steps:

Step 1: Productivity guru Stephen Covey used to talk about “beginning with the end in mind.” Using that approach, the first step in transforming your portfolio is to develop an ideal image of what you want it to look like. By this, I mean you should determine the asset allocation that makes sense for each account or group of accounts. For example, you might have one allocation for your retirement accounts, another for your taxable accounts and one for each of your children’s college accounts.

Step 2: Now that you have your ideal mapped out, you’ll want to compare each account’s current state to its ideal. To accomplish this, I recommend a tool like Morningstar’s Portfolio X-Ray, which is free, though you have to register with the site.

Step 3: If the most important factor driving your portfolio’s performance and risk is its asset allocation, it matters much less whether you pick Google’s stock over Apple’s. Instead, if the goal is to capture the returns of different asset classes, far more important is owning a basket of stocks, a basket of government bonds and so on.

That said, you still want to vet each individual holding to be sure you aren’t holding any ticking timebombs. I recall one portfolio held by an elderly couple. On the surface, it looked appropriate, with the bulk of their holdings in bonds. Upon closer examination, I saw that it was far riskier than it appeared, with bonds from corporate and government issuers that had spent time in bankruptcy.

Step 4: A well-worn rule of thumb dictates that investors should—to the greatest extent possible—hold bonds in retirement accounts and stocks in taxable accounts. The idea is to optimize tax efficiency, since bond interest and stock dividends are, for most people, taxed at different rates.

But times have changed. With bond yields so low, I think you can set aside this rule of thumb for now. Instead, I’d let your age and life stage drive this decision. Younger adults might want to have more bonds in their taxable accounts, where they would be accessible to meet unexpected expenses. Older folks, on the other hand, might want to have more bonds in their retirement accounts, to help meet required minimum distributions.

When should you start making changes? If you’ve evaluated your portfolio and decided it would benefit from some tweaks, I’d go ahead and do it. There may be a temptation to wait, based on your—or others’—opinion of where the market is headed. But in my view, this rarely works out.

Consider the market-timing advice offered recently by Goldman Sachs’s retired chief executive, Lloyd Blankfein. “There’s an old adage,” he wrote. “Don’t fight the Fed. Means that if the Fed is on a tightening course [i.e. raising rates], don’t be long [buying stocks]. And if the Fed is lowering rates, as now, don’t be short [selling stocks].” He issued this advice in September 2019.

At the time, the Fed had been lowering rates and stocks were indeed doing well, seemingly confirming Blankfein’s advice—except for one detail. About a year prior, in late 2018, the Fed had been doing the opposite: It had been in the midst of a multi-year course of raising rates and stocks were struggling. But then the Fed abruptly reversed course in 2019.

That’s the problem with “old adages” like this. If you’d been following Blankfein’s logic in 2018, you would have been scared out of the stock market. By the time you responded to the subsequent change in the Fed’s policy and bought back into stocks, you would have missed much of 2019’s 30% gain. The lesson: If your portfolio feels like a broker’s special, the best time to start making changes is now. Don’t delay—and certainly don’t base your decision on old adages.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include The Wager Revisited, Seven Paradoxes and Cut the Bonds

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include The Wager Revisited, Seven Paradoxes and Cut the Bonds

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Portfolio Makeover appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 1, 2020

Great to Gone

ON THIS DAY in 1888, George Cope died at age 65. Two days later, he was buried in Anfield Cemetery in Liverpool, England, where his younger brother Thomas had been laid to rest 40 months earlier.

Together, in 1848, the two brothers had launched a successful tobacco company, which would be acquired more than a century later by Gallaher Group, then a major U.K. multinational tobacco producer. Gallaher itself would subsequently be bought by Japan Tobacco.

At the time of his death, newspapers described George Cope as one of Britain’s richest men. His estate was valued at £274,923—equal to some $47 million, based on today’s exchange rate and U.K. inflation over the intervening 132 years.

Why my interest in Cope? He was my great-great-grandfather.

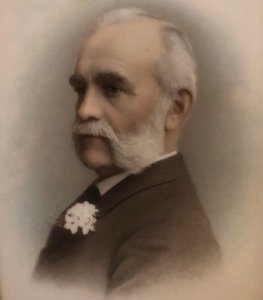

George Cope, 1822-88, co-founder of tobacco producer Cope Bros.

In an alternate universe where nobody spent my great-great-grandfather’s money, and instead his estate was invested in stocks and earned seven percentage points a year more than inflation, it would today be worth some $270 billion—more than the combined net worth of Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates.

But that isn’t exactly what happened. In fact, none of my great-great-grandfather’s fortune made it into my hands and, indeed, it never reached my mother and her two brothers. Instead, it took just two generations to run through the money bequeathed by one of Britain’s richest men.

I tell this story not to elicit sympathy—in any case, I’m not sure there’s much sympathy for tobacco heirs—but to highlight a crucial notion: Success often contains the seeds of its own destruction, and not just when it comes to family fortunes. Consider four examples:

1. Successful companies eventually grow so large that not only do they become bureaucratic and sluggish, but also they attract fierce competitors angling to steal their business. Today, we’re in awe of Alphabet’s Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Vanguard Group. Give it a decade or two, and we’ll likely view them as has-beens.

All this has been made worse by the pace of technological change. As companies grow ever bigger, it becomes more complicated and costly to upgrade to the latest technology—and that creates an opening for upstart competitors.

Have you noticed how clunky Facebook has become? Do you wonder why Vanguard unloaded its variable annuity business or shut down its cash management service? You can bet that thorny technology issues were a key reason. Similarly, when I was at Citi, the bankers had to know how to navigate 10 different computer systems, partly the consequence of multiple acquisitions over many years. Is it any wonder that Citi’s bankers struggle to deliver excellent customer service?

2. Economic booms are undone by the excesses they create. Robust economic growth allows marginal businesses to survive and prompts banks to loosen their lending standards. But all this can quickly unravel if growth slows or inflationary pressures drive interest rates higher. How many dubious businesses and dicey loans exist today? When the next recession rolls around, we’ll find out.

3. Investors are often victims of their own success. For instance, winning money managers attract heaps of assets from performance-chasing investors. Putting that new money to work compels them to buy more stocks, including stocks they’re less enthused about.

Almost inevitably, the results of these managers start to look more and more like the market averages—and often far worse. Why? Managers often notch handsome gains not because they’re skillful, but because their particular investment style is in vogue. But no stock-picking style stays in favor forever.

Success isn’t just poison for market-beating money managers. If investors—whether professional or amateur—are making money because of a rising market, they often imagine they know what they’re doing, even if their results are no better than the market averages. We saw this in the housing market in the early 2000s, and we’ve seen it repeatedly in the stock market.

Problem is, this ballooning self-confidence can lead folks to take ever-increasing risk. They might buy a fistful of rental properties with little or nothing down, shift more of their portfolio into stocks, purchase shares with margin debt or concentrate their bets on an ever-narrower slice of the stock market. But what happens when the market turns lower? Even if these investors aren’t panicked by tumbling prices, they may be forced to sell by their need for cash or by the leverage they took on.

4. Why do great family fortunes rarely last more than a few generations? Partly, it’s because the second and third generation, raised in affluence, don’t have the same hunger to make money.

But partly, it’s a simple matter of brutal math. For a family fortune to last in perpetuity and generate an income stream that rises with the general standard of living, the heirs face a daunting task, as I explained in a 2017 article. For starters, the heirs need to manage the money so that it earns an after-tax rate of return that’s higher than the pace of per-capita GDP growth—which is the rate at which general living standards tend to rise.

But that alone isn’t enough: To ensure the family fortune lasts in perpetuity, the heirs must also reinvest a sum each year equal to per-capita GDP growth. That annual amount might equal 4% of the fortune’s value. Problem is, if they do that, it can leave precious little to spend. To make matters worse, the annual amount available to each beneficiary will shrink if the number of heirs grows with each new generation.

How likely are the heirs to make the necessary sacrifices, so the family fortune stays intact? Have I told you about my great-great-grandfather?

Latest Articles

HERE ARE the six other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

Want to avoid Medicare premium surcharges? James McGlynn discusses IRMAA, the scourge of high-income retirees—and how to keep her at bay.

Yes, the SECURE Act makes it less financially attractive to bequeath your IRA to your children or grandchildren. But don’t expect a lot of sympathy from Richard Quinn.

“Many already worry about our society’s inability to manage money sensibly,” notes Rick Connor. “When you couple that with easy access to sports betting, what are the odds this will turn out well?”

Many financial experts recommend holding bonds in a tax-deferred account. Dan Danford thinks that’s kind of dumb.

“The best yardstick for success isn’t whether you beat a benchmark or your neighbor,” writes Adam Grossman. “Instead, the best measure is whether you meet your goals—while sleeping at night.”

Want a comfortable retirement? Don’t ignore inflation, forget to rebalance, take Social Security too soon or spend too much early in retirement, warns Rick Pendykoski.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Five Freedoms, Helping Them Along, Just in Time and Opening the Spigot.

Jonathan’s

latest books: From Here to Financial Happiness and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Five Freedoms, Helping Them Along, Just in Time and Opening the Spigot.

Jonathan’s

latest books: From Here to Financial Happiness and How to Think About Money.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Great to Gone appeared first on HumbleDollar.

January 31, 2020

What Are the Odds?

FROM AN EARLY AGE, I was amazed at the power of mathematics to model our world and solve real world problems. In engineering school, we studied a host of mathematical techniques that did just that. But I wish we’d spent more time on probability and statistics.

In 1989, I read a book that gave me a broader view of how probabilistic our world is and, at the same time, made me aware of how ill-prepared the general population is to understand these concepts. The book was Innumeracy by John Allen Paulos, a mathematics professor at Temple University. He later wrote several other books that expanded on these topics, including A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market—a must read for mathematically inclined investors.

Paulos shows that even the mathematically competent are susceptible to behavioral missteps. My favorite example is the widely held belief in the gambler’s fallacy—the notion that, say, a coin toss is more likely to be heads if you’ve previously had a series of tails.

What made me think of this recently was not an investment, but a basketball wager. On my local sports radio station, the hosts were discussing a bet on how many regular season games the Philadelphia 76ers would win. The wager in question was a “money line” bet, where you wager a fairly large sum to win a relatively small amount. The hosts thought it was a no-brainer and variously described the bet as “a sure thing,” “can’t miss,” a “lock” and “better than an FDIC guarantee.” In my view, the bet had a very good chance of paying off. But comparing it to a government guarantee went too far. Long shots sometimes win.

As you may have noticed, sports betting using mobile apps is expanding at a rapid clip. A recent story on MarketWatch reported that 14 states currently offer sports betting, with many more states considering it. It’s expected to be a $7 billion to $8 billion business by 2025.

This rapid growth is a result of a May 14, 2018, Supreme Court decision. I live in the northwest suburbs of Philadelphia. There are now six sportsbook establishments within a 30-minute drive, as well as seven sportsbooks available to me online. None of these existed 18 months ago. Professional sports leagues, which once considered gambling to be a grave threat, are now embracing this new revenue source.

It would seem that a solid grasp of probability and statistics would be essential for sports gamblers. But I doubt the general population has improved in this area. My bigger concern: The growth of sports gambling, especially among younger generations, will further blur the difference between gambling and investing.

Technology allowed the rapid development of day-trading in stocks. Many consider this a form of gambling. Similarly, a growing trend in sports betting is “in play” bets—wagers on offer throughout a game. Odds change after almost every play or every possession. The gambler uses a mobile sports betting app to monitor the odds. A wager may only be available for 10 or 20 seconds.

I have no idea how the growth in sports betting will shake out and or how it’ll impact society. But many in the financial community already worry about our society’s inability to manage money sensibly. When you couple that with easy access to sports betting, what are the odds this will turn out well?

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Triple Play, Read the Fine Print and Return on Investment. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609.

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Triple Play, Read the Fine Print and Return on Investment. Follow Rick on Twitter @RConnor609.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post What Are the Odds? appeared first on HumbleDollar.