Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 336

February 19, 2020

Keep On Keepin’ On

A NATIVE CHICAGOAN, I bailed out and am now a Southerner. Or at least a Florida Man. So I attend church each Sunday. If you attend church in the south, you will inevitably hear someone respond to a “how are ya?” with “well, I just keep on keepin’ on.”

With all the fanfare about this bull market, and especially large-cap technology stocks, it can be tough to keep on keepin’ on and stick to your long-term plan. Multiple financial news networks, finance Twitter and your neighbor Ted can, if you aren’t careful, trigger regret and cause fear of missing out, otherwise known as FOMO.

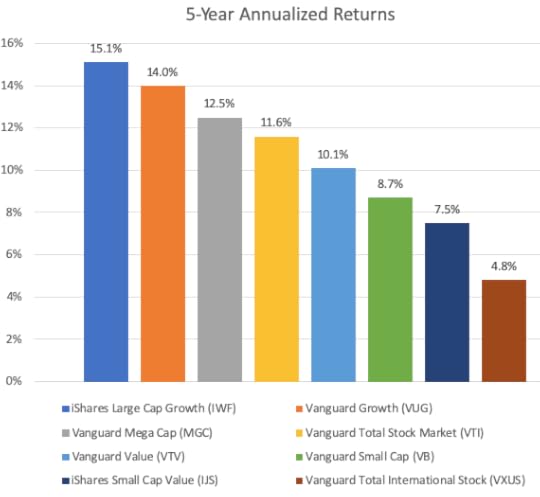

U.S. stocks had a stellar 2019, no question about it. But if an investor looks beyond U.S. large caps, returns haven’t been nearly as strong.

U.S. small caps have underperformed their large and mega-cap counterparts for more than a decade. Consider two exchange-traded index funds, Vanguard Mega Cap ETF and Vanguard Small Cap ETF. Over the past five years, the mega-cap fund is up a cumulative 80%, while the small-cap ETF is up “just” 52%.

U.S. value, historically a popular stock market tilt for those who pay attention to academic research, has lagged behind its growth counterpart over the same five-year stretch. Vanguard Growth ETF is up 93%, while Vanguard Value ETF is up a still respectable—but relatively disappointing—61%.

Foreign stocks have seen perhaps the biggest underperformance. Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF, a darling of the FIRE movement (to which I partially subscribe) is up 73% since early 2015, while Vanguard Total International Stock ETF is up just 27%.

Below are five-year annualized returns from Morningstar illustrating these sharp return differences. For grins, I included iShares U.S. Large Cap Growth and iShares U.S. Small Cap Value (and also to show I’m not playing favorites among ETF providers).

What is an investor to do with this data? “Nothing” may be the best answer, assuming you have a long-term plan in place. But if you’ve been dabbling in the market and not really following a plan, this may be the moment to set target portfolio percentages for different investments—and then make sure your portfolio matches those targets.

It’s easy to get caught up in the financial media’s hype and make short-term investment decisions based on emotion. Don’t. Even five years is short-term for most investors. For me, a 32-year old with no intention of tapping my portfolio for everyday expenses any time soon, I just keep on keepin’ on with my target asset allocation. My target allocation includes the underperforming sectors mentioned above, and I’m just fine with that.

Has it been a little challenging to see FAANGM (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google, Microsoft—or whatever the latest catchy acronym for the biggest tech stocks is) surge higher, while other areas of my portfolio underperform? Sure. But I also know that my skill at timing the market is poor. I’m much better off ensuring I have a low-cost, diversified portfolio of index funds for the long haul based on my risk and return objectives.

In fact, I take some solace from knowing that not every area of the stock market is rocketing along like a runaway freight train. If they all were, I would feel like a crash everywhere was imminent. But it seems the frothiness of U.S. large-cap growth stocks has yet to seep into other areas of the global market. Still, a Florida Man can dream.

Mike Zaccardi is a portfolio manager at an energy trading firm and a finance instructor at the University of North Florida.

He also works as a consultant to financial advisors on an hourly basis, helping with portfolio analysis and financial planning. Mike is a Chartered Financial Analyst and Chartered Market Technician, and has passed the coursework for the Certified Financial Planner program. His previous article was If Only.

Follow Mike on Twitter @MikeZaccardi, connect with him via LinkedIn, email him at MikeCZaccardi@gmail.com and check out his blog at Zmansmoney.com.

Mike Zaccardi is a portfolio manager at an energy trading firm and a finance instructor at the University of North Florida.

He also works as a consultant to financial advisors on an hourly basis, helping with portfolio analysis and financial planning. Mike is a Chartered Financial Analyst and Chartered Market Technician, and has passed the coursework for the Certified Financial Planner program. His previous article was If Only.

Follow Mike on Twitter @MikeZaccardi, connect with him via LinkedIn, email him at MikeCZaccardi@gmail.com and check out his blog at Zmansmoney.com.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Keep On Keepin’ On appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 18, 2020

Choosing Life

NONE OF US wants to contemplate our own mortality. But we all need to think about it—including thinking about life insurance.

I was lucky enough to have a long tenure with a large company that provided term insurance at reasonable prices. My employer provided two times our salary in coverage and we had the option to purchase additional coverage equal to eight times salary. I was also able to buy insurance on my wife’s life equal to three times my salary. Together, this coverage sufficed for my growing family for 31 years, right up to early retirement. In retrospect, I realize how lucky I was to maintain continuous employment with a strong company offering generous benefits.

My program for the Certified Financial Planner designation included an excellent course on insurance. The first and biggest challenge is figuring out how much life insurance you need. There are two main approaches:

Multiple of salary. This is a simplistic approach. Insurance companies often recommend six to 10 times an insured’s current salary. This doesn’t consider the specifics of an insured’s financial situation and could leave a family over- or underinsured.

Financial need. This is a detailed analysis of the surviving family’s likely needs. It takes into account existing assets and sources of income, and it considers the needs during all phases of the family’s future life, including childcare, college, weddings and even the retirement of a surviving spouse.

Once you determine how much insurance you need, the next big decision is what type: term or whole life.

Term insurance is relatively inexpensive and provides protection for a limited period, perhaps 10 to 30 years.

Whole life—also known as permanent insurance—is designed to provide protection no matter how long you live. Permanent policies can be costly and complicated, and they require a fair amount of expertise to evaluate them.

Where do you get life insurance? Like me, many folks get coverage through work. It’s often the easiest route, though not usually the cheapest if you’re in good health. Why not? Employees can often get coverage without any medical underwriting and insurers price the policies accordingly. On the other hand, if you have health issues, coverage through your employer may be your least expensive option.

You can also buy life insurance through insurance brokers and agents. The latter are often associated with a major insurance company. Finally, there are websites that allow you to get quotes from multiple companies.

I’ve been thinking about life insurance recently for a couple of reasons. My youngest son and daughter-in-law are expecting their first child in a few months. I plan to have a discussion with them about insurance. They’re smart, successful and healthy, so I don’t think they’ll have any issues getting the coverage they need. But they’re unlikely to spend decades with one employer, so it may make sense to get their insurance elsewhere.

I also recently talked to a family member about his need for life insurance. He’s in his early 40s, married and has two daughters. He’s had some significant health issues in the past that make him a greater-than-average risk. He owns a term policy that’s approaching the end of its coverage and he has the option to convert it into a whole life policy, but at significantly higher premiums. What about purchasing a new, standard-issue term policy? He likely wouldn’t pass the medical underwriting. He could qualify for a “simplified issue” or “guaranteed acceptance” policy—but, in both cases, he’ll face steep premiums. Someone in this situation would do well to engage a financial professional with expertise in hard-to-place life insurance.

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Step by Step, What Are the Odds and

Triple Play

. Follow Rick on Twitter

@RConnor609

.

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include Step by Step, What Are the Odds and

Triple Play

. Follow Rick on Twitter

@RConnor609

.

Do you enjoy the articles by Rick and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation .

The post Choosing Life appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 17, 2020

Garbage Time

MANY PARENTS assume that what counts are the big events, such as graduations or elaborately planned vacations. But I’ve always found that the best moments in life weren’t necessarily the ones circled on the calendar.

The stock market is a lot like family life. Forget trying to figure out the ideal moment to get in or out of the market. Instead, what really matters is the time spent sitting around in stocks.

Jerry Seinfeld affectionately calls his mundane interactions with his kids “garbage time.” He prefers that label to what most parents aim for—the impossible-to-meet “quality time” standard.

Seinfeld elaborates: “I’m a believer in the ordinary and the mundane. These guys that talk about ‘quality time’—I always find that a little sad when they say, ‘We have quality time.’ I don’t want quality time. I want the garbage time. That’s what I like. You just see them in their room reading a comic book and you get to kind of watch that for a minute, or [having] a bowl of Cheerios at 11 o’clock at night when they’re not even supposed to be up. The garbage, that’s what I love.”

In my experience, Seinfeld is absolutely right. I have found that taking my kids on an expensive vacation was not time—or money—better spent than the cumulative hours walking our dogs in our local park as a family or driving them to and from soccer practice.

Ryan Holiday, one of my favorite writers on the topic of inner reflection, points out that an elaborately planned vacation won’t deliver the expected happiness if you’re so consumed with everything going right and with taking the perfect pictures throughout the trip. He echoes Seinfeld’s premise, saying that some of his best memories with his family were not the actual vacation, but when the plane was delayed and everyone was hanging out in the airport. That’s true quality time, where you really get to enjoy one another.

There’s a parallel between the importance of “garbage time” in one’s personal life and the ordinariness of index-fund investing. In fact, there’s a well-worn saying among index-fund disciples that, “It is time in the market—not the timing of the market—that makes you money.” One example: If you missed the stock market’s best 10 days since 1980, your returns would have been more than halved.

We mistakenly think we can jump in and out of the market based on the stock market’s expensive price-to-earnings ratio or geopolitical events, but the data shows otherwise. This current bull market has done nothing but climb the proverbial “wall of worry” to become the longest in history. Even events like war are unpredictable when it comes to market returns. Ben Carlson recently pointed out that, during the two world wars, the stock market rose a combined 115%, though both had significant selloffs at the outset.

Our search for easy answers can be seen in magazine and internet articles that promise “13 Money Hacks to Turbocharge Your Investments” or “5 Ways to Spend Time with Your Kids When You Have No Time.” These headlines work because many people are rushing to get to the end, rather than enjoying the journey. While I don’t want to cast aspersions on those grinding it out to make ends meet—on the contrary, I have deep admiration for the American middle-class work ethic—I find these short-term strategies often end up setting us back.

In the market, as in life, hacking one’s way to anything can mean missing the most important opportunities. One of the best things about index-fund investing: It also allows us to spend more “garbage time” with those we love, rather than obsessing over market research and returns. This has an important compounding effect. Whether it’s money or family, “garbage time” is when we get the best return on our investment.

John Goodell is a government attorney who has spent much of his career advocating for military and veterans on tax, estate planning and retirement issues. His biggest passion is spending garbage time with his wife and kids. Follow John at HighGroundPlanning.com and on Twitter @HighGroundPlan. The opinions expressed here aren’t necessarily those of the U.S. government.

John Goodell is a government attorney who has spent much of his career advocating for military and veterans on tax, estate planning and retirement issues. His biggest passion is spending garbage time with his wife and kids. Follow John at HighGroundPlanning.com and on Twitter @HighGroundPlan. The opinions expressed here aren’t necessarily those of the U.S. government.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Garbage Time appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 16, 2020

Adding the Minuses

IT’S NO SECRET that mutual fund costs are critically important. In fact, when it comes to the performance of funds in the same category, they’re the single most important differentiator. In the words of Morningstar, the investment research firm, “If there’s anything in the whole world of mutual funds that you can take to the bank, it’s that expense ratios help you make a better decision.”

But how do you go about totaling up a mutual fund’s costs? And should you sell an expensive fund even when that sale might trigger taxes? Below is the approach I recommend:

Step 1: Track down a fund’s expense ratio. You can find the information on the fund company’s website, as well as on sites like Yahoo Finance and Barchart.

When you’re looking up a fund’s expense ratio, be sure to look it up by ticker symbol rather than by name. That will ensure you’re looking at the share class for the fund you own, since different share classes usually carry different fees.

To put the expense ratio in dollar terms, simply multiply the dollar value of your fund holdings by the expense ratio. Let’s say a fund charges a 1% expense ratio. You’d need to convert that to a decimal by dividing it by 100, which would give you 0.01. If you have $10,000 invested in the fund, you would multiply that $10,000 by 0.01. Result: The fund is costing you $100 a year.

Step 2: If you hold a fund in a regular taxable account, you’ll also want to quantify its tax cost. This information is often overlooked because it’s harder to find, but this is the perfect time of year to look. In the coming weeks, as you receive 1099 tax forms for your mutual funds, check for the line that reads “capital gains distributions.”

Be warned: There’s an important distinction between capital gains on the sale of a fund itself—which is your choice and entirely voluntary—and capital gains generated by trading inside the fund, which is at the fund manager’s discretion and not your choice at all. It’s the latter type of capital gain—the “distributions”— that you want to examine.

Determining the tax impact of these distributions takes a little work. But in general, you want to do the following calculations:

Multiply a fund’s long-term capital gains distribution by your capital gains tax rate. Your capital gains tax rate will depend on your overall income level and whether you’re married or single, so you might ask your accountant for help, assuming you use one.

Multiply short-term capital gains distributions by your marginal income tax rate—that is, the rate that applies to your regular income.

If your state levies an income tax, do these same calculations with your state tax rates.

Step 3: Add together the above expenses and taxes. If your fund’s expenses are $100 a year, and the taxes on capital gains distributions are $200, the fund is costing you a total of $300 per year.

Step 4: To put these numbers in context, divide your total cost by the value of your fund holdings. For instance, $300 divided by $10,000 equals 3%. To judge that figure, I would use these rules of thumb:

Total fees and taxes of less than 0.20%: Excellent

Between 0.20% and 0.40%: Good

Between 0.40% and 1%: Fair

More than 1%: Unacceptable

Step 5: In the above example, we calculated a total cost of 3% a year, which puts the fund squarely in the unacceptable category. If any of your holdings fall into this category, you have a few choices:

You could donate the shares to charity.

You could sell the fund in a year when you have an offsetting loss on another investment.

If you’re near retirement, you could hang on until your tax rate is lower.

You could give the fund to one of your adult children, whose capital gains tax rate might be lower—and perhaps even zero.

You could sell the fund. If this is the option you want to pursue, continue on to the next step.

Step 6: Suppose you’ve determined that a fund is overpriced and you want to sell. If the fund isn’t in a retirement account, the sale might trigger a tax. How do you know if the sale would be worthwhile? I recommend this calculation:

Determine the tax you’d owe if you sold. Again, if you use an accountant, you might ask him or her.

Divide that tax by the total annual cost of holding the fund. For the latter number, head back to Step 3.

This calculation will tell you how many years it would take to break even on the sale. For example, if the estimated tax bill from selling was $1,000, and your annual cost of holding the fund is $300, it would take you about three years to break even. If it were me, I would do this trade. But if the breakeven point were far longer—say 10 or 20 years—then I wouldn’t be as quick to sell. Instead, you might opt to hold on until you were ready to pursue one of the other options outlined in Step 5.

Keep in mind two caveats. First, you’ll notice that, in these calculations, I’m looking at the absolute cost of an investment and not comparing it to the cost of any alternative. This might seem unfair. But there are many investments today that are so low-cost and so highly tax-efficient that they’re virtually free—and thus I think that zero is an appropriate benchmark for comparison.

Second, I acknowledge that high expenses may be justified by a narrow slice of funds. But these outliers are mostly private equity, venture capital and sometimes hedge funds. What we’re talking about here are ordinary mutual funds, where high costs generally don’t correlate with better results.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Believe It or Not, Portfolio Makeover and The Wager Revisited

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman’s previous articles include Believe It or Not, Portfolio Makeover and The Wager Revisited

. Adam is the founder of

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He’s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Adding the Minuses appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 15, 2020

Rule the Roost

I AM AGE 57 and I’m planning to move, so you might imagine I’d be interested in the best states to retire. On that score, there’s plenty of advice available.

Bankrate says the best option for retirees is Nebraska, followed by Iowa, Missouri, South Dakota and Florida. Meanwhile, WalletHub gives the nod to Florida, with Colorado, New Hampshire, Utah and Wyoming rounding out the top five. Want a third opinion? Blacktower Financial Management puts Iowa at No. 1, with Minnesota, Vermont, Wisconsin and Nebraska also ranked highly.

The three surveys use somewhat different criteria, but all consider things like cost of living and crime. What about New York, where I currently live? Depending on which survey you look at, the Empire State ranks 42nd, 37th or 49th. Clearly, I should have left years ago.

What about my destination? Pennsylvania ranks 11th and 13th, which sounds promising, but also 34th, which doesn’t. But whatever the rank, it wouldn’t make a jot of difference to my decision. Why not? I don’t think your retirement destination should hinge primarily on the crime level, the weather, the number of museums or any of the other criteria that these surveys use. Instead, it should be about people.

My daughter and son-in-law live in Philadelphia—as do some friends—so that’s where I’m moving. Happiness research, as well as my own experience, has taught me that it’s crucial to surround yourself with those you love. Indeed, when retirees tell me they are moving to a place simply for the warmer weather, the low taxes or the affordable housing, I worry that they’re making a terrible mistake—because they may be miserable without the network of friends they leave behind.

Heading home. While I think being close to friends and family is paramount, I do have secondary criteria. Indeed, it’s crucial to figure out exactly what sort of house you want, because buying the wrong place is such a costly mistake.

Between title insurance, moving costs, legal fees, transfer taxes, mortgage-application fees, the real estate commission and more, you could easily lose a sum equal to 10% of a home’s value if you buy and then sell. That cost may be okay if you live in the place for 10 years, but not if you have a change of heart after 10 months.

Want to avoid making such a costly mistake? Research suggests we aren’t very good at what’s called affective forecasting—meaning we don’t have a good handle on what will make us happy. To counter that problem, some months ago, I created a wish list of what I want in a house and I’ve been refining it ever since. Here are my 10 criteria, pretty much in order of importance:

I want a place where, if my physical deterioration necessitates it, I can live on one floor. That means I want at a bathroom on the same floor as the kitchen and living room, and I’d prefer the entire house be no more than two stories.

I want a place within walking distance of my daughter and son-in-law—but not so close that any of us could casually drop by to borrow the sugar.

I want an extra bedroom for guests. (This is not a blanket invitation.)

I want outdoor space—either a small garden or a balcony. As I get older, spending time outside has become increasingly important to my sense of well-being.

I want to be able to walk to restaurants and the grocery store.

I want to have relatively easy access to roads or trails where I can bicycle without too much cavorting with cars.

I don’t want high carrying costs. I looked at apartments in Philadelphia’s prestigious Rittenhouse Square. While I wasn’t put off by the prices, I was deterred by the maintenance payments, which can run as much as $1,900 a month for a two-bedroom apartment. Among other items, that monthly payment covers a chauffeured car that’s available to residents. Yes, you read that right.

I want to look out the window—and walk out the door—and see people. I like meandering down the sidewalk and exchanging smiles with strangers (and, thus far, I’ve managed to do so without triggering a police visit).

While I’d remodel the place if I had to, I’d rather not. I’ve overseen enough remodeling projects in my lifetime. I don’t want the disruption and it isn’t how I want to spend my time.

I’d rather not have a basement or, failing that, a finished basement. I realize my aversion is somewhat irrational. But to me, basements mean vermin and possible flooding. What if the basement has French drains? Puh-leeze. That’s just an admission of defeat.

Following rules. Even if homebuyers draw up this sort of detailed wish list, there’s still a danger that—in the heat of the moment—they’ll make some snap judgment that overrides the rules laid down earlier by their calmer self.

Don’t think that could happen? Folks often ignore rules, even when those rules are designed to save their life. Consider the tragedy on Mount Everest in May 1996, which has been the subject of countless articles and books, including Jon Krakauer’s bestseller Into Thin Air. The expedition leaders instructed the amateur climbers involved that, if they hadn’t reached the summit by 2 p.m., they should turn around. Yet—once they were on the mountain—many simply ignored this rule. In all, eight climbers died, including two expedition leaders who were supposed to enforce the rule.

None of us, I hope, will die in the act of house hunting. Still, there’s an important lesson here: We often draw up sensible rules for ourselves—and then blithely ignore them, often to our own detriment.

We might get caught up in a bidding war and pay too much for a house. Or focus on some feature that isn’t crucial, while forgetting the criteria we fundamentally care about. That’s why I like drawing up rules and then reviewing them right at the moment when I make the decision. Such rules won’t just help us make smarter choices when buying a home. They can also help with numerous other financial decisions, including what car we buy, how we manage our portfolio and what college our teenagers select.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE the six other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

“Some observers have accused the entire active-management business of being a scam,” notes Gary Karz. “Don’t want to be scammed? The default choice should be index funds.”

John Yeigh may be retired, but he has little use for bonds. His recommendation: Keep three-to-five years of portfolio withdrawals in cash—and the rest in stocks.

Want to give to charity? If you’re age 70½ or older, a qualified charitable distribution is likely your best option. James McGlynn explains.

“If the fear of missing out is too strong to suppress, here’s my recommendation: Risk just a small amount, view it like a lottery ticket—and hope for the best,” writes Adam Grossman.

Our financial success, or the lack thereof, usually isn’t built on a single decision. Instead, says Rick Connor, it’s the summation of thousands of small choices made over many decades.

“We used to call benefits the ‘hidden paycheck’,” recalls Richard Quinn. “But I wonder if today’s workers give that hidden paycheck a second thought.”

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Nobody Told Me,

Great to Gone

and

Five Freedoms

.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

@ClementsMoney

and on

Facebook

. His most recent articles include Nobody Told Me,

Great to Gone

and

Five Freedoms

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Rule the Roost appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 14, 2020

Losing My Balance

CNBC ANCHOR Becky Quick recently summed up today’s retirement investing dilemma in one sentence: “You’re never going to make enough money if you have 40% of your money in bonds.” She, along with many pundits, believe the old standby recommendation to invest 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds—the classic balanced portfolio—is dead. Google “60/40 asset allocation” and the majority of recent articles have titles that include such words as “eulogy,” “endangered,” “dead,” “the end of” and “not good enough.”

Likewise, I regularly chat about investment strategies with friends and none is rushing to buy bonds or extend maturities at today’s low interest rates. Even “bond king” Jeffrey Gundlach suggested in a December 2019 interview that “corporate bond exposure [in the U.S.] should be at an absolute minimum level right now.”

While many articles and pundits deride the old balanced portfolio, surprisingly few articles suggest a simple yet sound alternative. CNBC’s Quick inadvertently identified it when she stated, “I have some cash so that I make sure that I have a cushion… but I don’t have anything in bonds.”

Quick’s views mirror that of my friends and me, as we invest in today’s low-interest rate environment. Our approach: Maintain enough cash to weather a stock pullback, while investing the rest entirely in stocks. How much should you keep in cash? Think about how much money you need each year from your portfolio to supplement other income sources, like Social Security, pensions and income annuities.

Since the Second World War, there have been a dozen major declines of 20%-plus. From the start of these bear markets, it took an average of almost three years for share prices to return to their earlier peak, with the absolute longest taking seven-and-a-half years.

In other words, the historical data suggests retirees might hold cash equal to three years of portfolio withdrawals at a minimum and perhaps five years if they’re more conservative. Buoyed by this backup source of spending money, we then should have little to worry about if we invest the balance of our assets in a diversified stock portfolio, even though the resulting stock allocation will likely be significantly above the old 60% recommendation.

Obviously, folks still working can hold even less cash. I was 100% invested in stocks when I was in the workforce. But retirees may have to be more conservative with their cash allocation, unless they have the flexibility to generate extra spending money by, say, initiating Social Security payments, working part-time, borrowing or selling nonfinancial assets.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. His previous articles include Our To-Do List, Death and Taxes and Take a Break.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Losing My Balance appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 13, 2020

Make Less Keep More

“PERFORMANCE COMES and goes, but costs roll on forever,” said Vanguard Group’s founder, the great John Bogle. It’s been just over a year since Jack passed away.

I think he would have approved of Vanguard’s recent announcements that it had reduced fees on 56 funds and eliminated trading commissions to buy and sell stocks and ETFs. The latter followed similar announcements from other major discount brokers. All of this is good news—especially right now.

Why? Vanguard recently forecast that U.S. stocks will average just 3.5% to 5.5% a year over the next 10 years, while U.S. bonds might notch 2% to 3%. Research Affiliates is even more pessimistic, projecting U.S. stock returns that are barely above inflation. Yes, over the past decade, the S&P 500 returned more than 13% a year. But over the prior decade, its return was negative. There’s a decent chance that the 2020s will look more like the 2000s than the 2010s.

If returns are indeed low, investment costs will eat up a larger percentage of our gains—which is why the news on investment costs is good. But maybe it isn’t quite as good as folks imagine. Here are five thoughts on the recent fee-cutting war among Wall Street firms:

1. Commissions are, for many investors, a fairly small cost. Individual investors often pay far more in advisory and other fees, which might total 1% or more of their portfolio’s value. Similarly, beyond commissions, institutional investors can pay hefty sums to trade, including market impact costs—the tendency for their own trading to drive security prices up and down, thus making it more expensive to buy and sell investment positions.

2. Investors also need to be aware of bid-ask spreads, the difference between the higher price at which they can currently purchase a security and the lower price at which they can sell. The difference—which represents the cut taken by Wall Street’s market makers—is typically minimal for liquid securities, but it can be several percentage points for illiquid securities.

3. I view much of the fee-cutting not as proactive, but rather as a response to competitive pressures. For instance, like Vanguard, Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) recently reduced its fees. DFA relies heavily on investment advisors to steer their clients to DFA funds. Those advisers are being courted by low-cost index and factor-based ETFs, which is putting pressure on DFA.

4. A good advisor can help investors develop a plan, choose the right asset allocation, invest in appropriate securities and avoid behavioral mistakes. But investors should only compensate advisors a reasonable amount—and they should avoid paying for advisors or services that are unlikely to add value.

Investors might invest on their own or use one of the robo-advisors. The latter offer simple yet smart advice for minimal cost. By contrast, high-cost advisors and funds are likely to have relatively inferior performance, which will be especially problematic if we suffer a low-return environment.

5. The reason index funds have grabbed an ever larger percentage of industry assets is because they effectively allow investors to separate investing from speculating. What counts as speculation? I’m not just talking about day traders and others who buy and sell like crazy. Arguably, active money managers are also speculators, as they try to guess which stocks and bonds will outperform.

In fact, some observers have accused the entire active-management business of being a scam. Don’t want to be scammed? Whether you’re using an advisor or investing on your own, the default choice should be index funds. Remember, any higher-cost investment is more likely to lower your returns than improve them.

Gary Karz is a Chartered Financial Analyst, publisher of

InvestorHome.com

and author of

The Peaceful Investor

.

He enjoys skiing, hiking, biking and snorkeling. Follow Gary on Twitter

@GKarz

or email him at

host@investorhome.com

.

Gary Karz is a Chartered Financial Analyst, publisher of

InvestorHome.com

and author of

The Peaceful Investor

.

He enjoys skiing, hiking, biking and snorkeling. Follow Gary on Twitter

@GKarz

or email him at

host@investorhome.com

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Make Less Keep More appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 12, 2020

Count the Noncash

MOST PEOPLE think of their earnings as what they receive in their paycheck. But that’s not the case. Typically, it’s more—sometimes far more.

That brings me to my first topic: chief executive officers. You’ve all heard the numbers: This or that CEO was paid a salary of $30 million. Actually, no CEO was paid that sum or close to it. Those amounts represent total compensation, which might include their regular salary, stock awards and options, and the projected future value of a pension. Much of that compensation is at risk. Stock options may expire worthless.

Also, most CEO pay isn’t in the tens of millions. Those stratospheric numbers apply only to some CEOs of the world’s largest companies. Most CEOs have compensation of less than $400,000, lower than the minimum salary for a rookie player in the NFL.

Admittedly, some CEOs receive total compensation that may not reflect solid performance. Simply put, they don’t deserve it. But we still need to keep the numbers in perspective.

For example, I looked at the compensation of the CEO of an S&P 500 company with 144,500 employees. His cash compensation was $4,987,635, equal to $34.52 for every worker at the company. His total compensation equals $153.67 per worker. Based on what I could find, the average hourly worker earns $16 to $18 an hour. Let’s call it $17. At that rate, their annual pay of $35,360 means that—if they each got their share of the CEO’s entire compensation—the 144,500 employees would receive a raise of 0.4%, equal to seven cents per hour.

While some CEO pay may cause consternation, I’d argue more Americans are adversely affected by the salaries of sports figures and celebrities, because their incomes drive up ticket prices for sporting events, concerts and movies. Which brings me to my second topic: the typical employee.

Understandably, workers tend to look at only part of their pay—the cash they take home. There are, however, the various payroll taxes paid by employers, which help bankroll Social Security, Medicare, and disability and unemployment coverage. Then there’s the employer cost for various employee benefits, including health insurance, an employer’s retirement contributions and time off with pay. Some of these benefits are tax-deferred or tax-free. They all have real value. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employee benefits cost an average $11.60 per hour, or 31.3% of total compensation. For most government workers, benefits packages are even more generous.

Some people would say, “So what? You can’t eat benefits.” Maybe so. But trying to replace those benefits on your own would mean buying a lot less food with your remaining cash. We used to call benefits the “hidden paycheck.” But I wonder if today’s workers give that hidden paycheck a second thought. Rather than seeing the portion paid by their employer, they focus only on their own payroll deductions.

When I look at the depressing numbers that detail Americans’ modest savings, rampant spending and hefty debt, a somewhat heretical thought comes to mind: Do Americans need more done for them? Should we focus more on noncash compensation? Have past efforts to encourage saving and overall prudent financial behavior failed?

And if so, should we care? I think there’s no choice but to care, because of the potentially adverse effects on society. That raises a thorny question: How do we approach the problem?

Should we simply increase Social Security taxes on both employers and employees, thereby assuring higher retirement benefits? Should we increase the tax incentives that encourage personal savings? Should we promote more stock ownership and profit sharing by employers? I’m thinking all of the above.

Some would argue for simply raising the minimum wage. But that’s not a fix to our long-term problems. It affects a small segment of workers. It’s also treading water, because consumer prices will rise to absorb the cost not only of those directly affected by the new minimum wage, but also those who are earning more and who get their compensation increased, so they maintain their position relative to minimum-wage workers.

My logical side says individuals should be able to manage their financial life on their own. But the evidence tells me otherwise—so my practical side says we need new initiatives, including a greater focus on employees’ noncash compensation.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include It’s a Stretch, Going Without and Getting Catty. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include It’s a Stretch, Going Without and Getting Catty. Follow Dick on Twitter @QuinnsComments.

Do you enjoy articles by Dick and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation .

The post Count the Noncash appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 11, 2020

Step by Step

ONE OF MY favorite movies of recent years was Hidden Figures. There’s a pivotal scene where the hero, Katherine Johnson, realizes they need to use an ancient numerical technique known as Euler’s Method to solve the trajectory equations for John Glenn’s mission. This involves breaking a complex problem into very small pieces, solving each part, and then summing them to get the solution.

Over my engineering career, I used various numerical integration techniques to solve complicated problems. It gradually occurred to me that this approach was a good metaphor for how our world works—and could be applied to our financial life as well.

Our world is massively complex and I make no claims to fully understand it. Still, a simplified model can help. Our daily actions make up the small parts of a complex system. These include how we vote, what we buy, who we marry, where we live, our career choices and countless other actions. The world acts as a giant integrator, taking our micro actions—along with everyone else’s—and integrating them to create the macro state we experience every day. Simply put, our world is the sum of all of our collective actions and interactions.

What I like about this model is it reminds me that my actions do matter, but that they must be understood in the context of the decisions of others. If my candidate loses, I need to think about why more people disagree with me than agree. If my favorite store goes out of business, I should ask why others are shopping elsewhere. It’s empowering and humbling at the same time.

I recently had a medical procedure that kept me homebound for a few weeks. One of the things I noticed was how many Amazon deliveries my little street of 20 houses saw each day. I would guess at least 10 deliveries per day. Is Amazon a predatory company succeeding by nefarious means—or is it successful because half of my neighbors like its prices and the convenience of its services? My simplified world model points to the latter. Millions of people making independent choices have led to Amazon’s success.

The application to our financial life is straightforward. There have been a number of articles discussing the latte effect on our finances. Such micro decisions help determine our financial health. To be sure, it’s rare for a single choice to prove decisive and, even if we make good decisions, we can be knocked off course by the actions of others.

Still, our financial success, or the lack thereof, is usually the summation of a lot of individual choices over a long period. Good choices—saving regularly, indexing, deferring taxes—integrate and compound to provide a secure financial future. Bad choices—carrying credit card debt, paying high investment costs, buying a new car every three years—have a similar but opposite impact. But don’t despair: There are lots of second chances and lots of opportunities to correct our mistakes, so we get on course for a sound financial future.

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include What Are the Odds,

Triple Play

and

Read the Fine Print

. Follow Rick on Twitter

@RConnor609

.

Richard Connor is

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous articles include What Are the Odds,

Triple Play

and

Read the Fine Print

. Follow Rick on Twitter

@RConnor609

.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Step by Step appeared first on HumbleDollar.

February 10, 2020

Gifts That Give Back

IF YOU’RE in your 70s or older and you are charitably inclined, it’s time to get acquainted with one of your best financial friends: the qualified charitable distribution, or QCD.

A QCD is a distribution that’s made directly from your IRA to an organization eligible to receive tax-deductible contributions. A QCD counts toward your annual required minimum distribution, or RMD. But unlike a regular RMD, the QCD won’t add to your taxable income for the year—a potentially huge advantage. You must be at least age 70½ to make a qualified charitable distribution and the maximum amount in any given year is $100,000.

QCDs have recently become more valuable. Thanks to 2017’s tax law, the standard deduction has roughly doubled. That means fewer taxpayers are itemizing their deductions, so they aren’t getting any tax break for their charitable contributions. What to do? If you’re 70½ or older, you can take part of your regular RMD—which would be taxable—and replace it with a nontaxable QCD. In effect, you’re making a tax-deductible charitable contribution, even if you’re claiming the standard deduction.

Because your taxable income is lower, you could also enjoy a slew of other benefits. For instance, reducing your taxable RMD might keep your income below one of the thresholds for IRMAA, short for income-related monthly adjustment amount. It’s a topic I recently wrote about. Breaching one of the IRMAA thresholds by $1 can mean a substantial increase in your Medicare premiums.

To do a QCD correctly, keep a few key details in mind. The IRS does not allow distributions to donor-advised funds or private foundations. The distribution cannot come from a 401(k). The distribution can come from an inherited IRA, assuming the beneficiary is over age 70½. The recent SECURE Act, which raised the RMD age to 72, did not increase the QCD age. It remains age 70½.

The custodian or trustee for your IRA must handle your distribution to a qualified 501(c)(3) public charity. If you withdrew $1,000 from an IRA and then contributed the money to a charity, the $1,000 would count as taxable income and you’d have to pay taxes. But if the $1,000 is transferred directly to the charity, or if you receive a check made out to the charity and then donate the check, the $1,000 won’t be considered part of your taxable income.

The tax filing is easy enough. On your Form 1040 federal tax return, report the full amount of the charitable distribution on the line for IRA distributions, along with any regular taxable withdrawal. But on the line for the taxable amount, exclude the sum you donated with your QCD and enter “QCD” next to the line.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of Next Quarter Century LLC in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers. His previous articles include Danger: Cliff Ahead, Early and Often and Don’t Get an F.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of Next Quarter Century LLC in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers. His previous articles include Danger: Cliff Ahead, Early and Often and Don’t Get an F.

Do you enjoy HumbleDollar? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Gifts That Give Back appeared first on HumbleDollar.