Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 342

December 21, 2019

Eyes Forward

���DON���T STOP thinking about tomorrow,��� sang Fleetwood Mac. It���s a shame they weren���t financial advisors.

We save money today so that we���or our heirs���can spend at some point in the future. A good tradeoff? I strongly believe that it is, and you wouldn���t be a HumbleDollar reader if you disagreed. Still, during this season of holiday shopping joy, it���s worth reminding ourselves that, yes, we should indeed think about tomorrow.

Living for Today. There are two major reasons to focus on today and, I���ll readily concede, they are compelling. Reason No. 1: It offers the chance for immediate gratification. We get the thrill of spending right away and, perhaps just as important, we don���t have to summon any self-control or ponder alternative uses for the money. We see it, we like it, we buy it. End of story.

Reason No. 2: We may not be around tomorrow. I���m not sure many people lie on their deathbed thinking, ���Wow, it���s such a bummer, I have $3,000 in my IRA that I never got to spend.���

Still, many Americans appear to be leaving nothing to chance, their behavior today suggesting they don���t expect many tomorrows. You can see this in the failure to save for retirement, the refusal to buy income annuities, the preference for lump sum payouts over monthly pension checks, and the rush to claim Social Security at age 62, the earliest possible age. For most of us, this pessimism isn���t justified, as the actuaries will attest. But it will, alas, be justified for an unlucky minority���and perhaps we���re overly influenced by stories of folks who die relatively young.

Thinking About Tomorrow. If immediate gratification and the risk of an early demise drive us to spend today, what might persuade us to delay until tomorrow? I can think of five rock-solid reasons.

First, waiting to spend offers the chance for eager anticipation���a drawn-out pleasure that, I���d argue, easily surpasses the fleeting satisfaction delivered by impulse purchases. For instance, I try to plan my vacations far in advance, so I have months to look forward to each trip.

Second, if we delay spending, we���ll typically make more thoughtful decisions���and we���re less likely to end up with stuff we regret buying. Don���t believe me? Might I suggest touring your basement? How about looking through your closets?

Third, by spending a little less today so we have money to spend tomorrow, we buy ourselves a sense of financial security. I view this as one of life���s great financial tradeoffs. By eschewing some of today���s purchases and instead socking away the money, we buy ourselves long-term happiness. That happiness comes from knowing we can easily cover the bills that lie ahead, we won���t be knocked off course by surprise expenses and we aren���t deeply in hock to the credit card company.

That brings me to my fourth reason: It isn���t simply that $100 not spent today means we���ll have $100 to spend in the future. With careful investing, that $100 of forgone spending might become $400 or $500 of retirement spending, thanks to investment compounding. Similarly, $100 borrowed today might cost $200 or $300 to repay, once interest is factored in.

Finally, we should never forget that there���s a high likelihood that one day we���ll be retirees. For instance, if we���re age 20 today, there���s an 85% chance we���ll live to age 65. Make no mistake: Our future self will be grateful for any money we save and for all the debt we don���t take on. Like exercising regularly, not smoking, drinking in moderation and eating healthily, spending less today shows that we care about the person we���ll become.

All that said, we need to strike a balance between today and tomorrow. We shouldn���t delay all gratification. For 80% of the population, this isn���t a risk. If anything, most people need to focus even more intently on their financial future. But for the frugal 20%���the sort of folks who regularly visit this site���there is indeed a risk that they have their gaze too firmly fixed on tomorrow.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Low Blows,��Saving Myself��and��Breaking Bad

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Low Blows,��Saving Myself��and��Breaking Bad

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Eyes Forward appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 20, 2019

Getting Catty

CATS ARE NOT my favorite animal. They don���t like me, either. I���m allergic to them. If I go into a house with cats, within minutes I have trouble breathing. I once saw Cats on Broadway. Even the actors dressed like cats rubbing against my leg creeped me out.

Recently, I was in a restaurant. In the booth opposite were two young women, probably in their mid-to-late 20s. They were chatting away between texts. Occasionally, I heard the words ���money��� and ���spending.��� My ears perk up when I hear those words. My wife knows that, so she gave me the glare that said, ���Mind your own business.���

Then it happened. The younger of the two ladies said, ���I want to get a cat.����� There���s my wife���s glare again.

The older one responded, ���Are you sure you can afford it?��� Oh my, I���m thinking this discussion is too good not to participate in. How do I get an invite? A glance over at the booth, hoping for eye contact, was a failure.

���Did you hear that?��� I whispered to my wife.

���Yes, and don���t say a word��� was the reply, accompanied by another glare.

The young lady hadn���t thought about cost, so her friend obliged with information via Google. ���About $1,000 a year.���

That was followed by a moment of silence, after which the cat lover responded, ���So what, I spend that much on makeup.���

Jumping on this illogical response, the older friend said, ���But this is an additional $1,000.��� Good for her.

That makeup number shocked me, although I don���t know why, as I frequently accompany my wife to the Estee Lauder counter. A��survey of 3,000 women found they spend $300,000 on makeup over a lifetime. As with much survey data, it���s questionable. That said, if a 20-something spends even $1,000 a year, it���s still a lot of money.

For the record, Americans spent over $72 billion dollars on their pets in 2018 and the amount has been climbing each year. About 30% of households have a cat, with an average of two per household. Most buy their animals a Christmas present.

Which brings us back to the feline project. What followed in the nearby restaurant booth was a detailed discussion about likely costs: the vet, food, litter, toys���though, I���m disappointed to report, Halloween costumes were left out.

I���m thinking to myself, if you have to go through all this to see if you can afford a cat, you probably can���t. But then out came a pad and pencil and use of the calculator on her phone. This was getting as serious as retirement planning. And still no opening for me to give my two cents.

I was pretty sure a cat was going to find a home, regardless of finances, but then came the clincher as they received the dinner bill: They asked the server. Her response was instantaneous and devoid of analysis. ���Sure, you should get a cat,��� the waitress said.

Had I gotten the opening I sought, I would have asked the cat-loving millennial how much she was saving each payday and whether she had retirement funds, and suggest that if she needed a calculator to decide on a pet, think again���all in a friendly tone mind you. Alas, my two cents were still in my pocket.

The two young ladies were off to the movies. And guess what? The cat fancier insisted she could afford to treat her friend.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Give Until It��Hurts, Food for Thought and Fashion Statement.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include Give Until It��Hurts, Food for Thought and Fashion Statement.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Getting Catty appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 19, 2019

When It Rains

TWO WEEKS AFTER my husband���s death, we held a memorial service for local friends and family. Days later, after a reasonable amount of online research, I visited a car dealer.

It���s my experience that bringing at least one youngster along speeds up dealmaking, plus a parent can get unvarnished opinions about life in the backseat. So I brought along my 13-year-old. The two of us test drove two used cars and bought one of them.

The next day, I drove to work in the city, instead of taking a train from the park-and-ride lot, as I’d done for the prior decade. My goal was to shorten my commute and reduce my hours away from home. This ended badly when I slipped on wet pavement in a parking garage, resulting in an injury that required surgery and time off work.

Having never endured such an injury before, it was a shock to realize that���for the first time in my adult life���I was neither earning nor saving money, especially during a period of such high expenditures. Further, we���d lost all my husband���s future cash flow and his sharing of family responsibilities. Would that I had a partner and decades of earnings to recover the lost cash. But instead, I was on my own, launching three young adults.

I had read about the “widowhood��effect.” I was at elevated risk of illness, injury or death. I had been careful. But I���d already exceeded the three-to-five days off work allotted for a death in the immediate family. On top of that, we grieving people are often told to stay busy and try to get back to normal routines.

While anyone can lose their footing on a rain-soaked walkway, possibly nothing bad would have happened if I���d kept to my familiar commute or, even better, stayed home from work another week or two. But all this was futile what-ifs. I set aside such thoughts, and focused on my work as executor of the estate and on helping the children in their grief.

The financial work was made simpler by our prior planning, with a straightforward will, clear beneficiaries named on financial accounts (with one exception) and a family revocable trust, meaning my husband���s estate didn���t need to go through probate. An ongoing relationship with the lawyer who���d done this work also came in handy for this and other matters.

The confluence of the loss of my spouse and a temporarily disabling injury became the ultimate test of our rainy-day fund. Cash to cover three-to-six months of expenses is a sizable chunk of money. Some experts advise holding less, if you���re willing to use loans or credit cards in a pinch. But the fact is, that ���pinch��� could involve a lot more than typical spending.

As it turned out, our funds proved sufficient to weather the early problems caused by losing my credit cards, debit cards and license, followed by the cost of the funeral, a down payment on a newer car, daily living expenses and medical costs. Nevertheless, it was alarming to watch my emergency money shrink. I am now rebuilding our family���s rainy-day fund, as well as restructuring our financial accounts to make the whole of it simpler and easier to manage.

Here are four key lessons from this period:

The moment of loss is too late to begin saving money. You must begin sooner and have some confidence you���re targeting the right amount. It���s easier emotionally to plan for a flood or hurricane than to plan for your own death or the loss of a loved one. Whatever your strategy, the goal is a resilient financial environment for your family. Include legal planning in this.

Having one bit of bad luck doesn���t preclude having more of the same. Keep a calm demeanor throughout and stick with your financial strategy. It will pay off in the long run.

Many post-death tasks have specific timelines. For instance, there���s 60 days to roll over an IRA if you���re the spouse and you receive a distribution. Call the customer service numbers on statements. Read any paperwork that firms send you. Return it promptly. Keep moving forward with one eye on the calendar.

Along with your financial plan, invest in friends, family and community. If you run out of money or the ability to handle matters, it���s good to know that others will show up for you. The support of friends and family in our community saved us thousands in direct expenses, as well as buoying our spirits at life���s lowest moments.

Catherine Horiuchi is an associate professor in the University of San Francisco’s School of Management, where she teaches graduate courses in public policy, public finance and government technology. This is the third article in a series. Catherine’s two earlier articles were��At the End��and The Aftermath.

Catherine Horiuchi is an associate professor in the University of San Francisco’s School of Management, where she teaches graduate courses in public policy, public finance and government technology. This is the third article in a series. Catherine’s two earlier articles were��At the End��and The Aftermath.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post When It Rains appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 18, 2019

Three Life Lessons

IT WAS 1989��and I was living at home with my parents after obtaining my finance degree. I still harbored dreams of playing professional baseball, but let���s just say I also embraced learning about the financial-planning trade.

A year later, my why���my purpose���was born. In 1990, my father���s employer went bankrupt. As my 59-year-old dad looked for a new job, I felt the stress level in the house rise. My mother didn���t understand why it took so long for him to find work, didn���t offer much support and complained about how his new boss didn���t pay him like his former boss. Nobody deserves to feel this way at this time in his or her life���especially after ���gifting��� three kids a college education. Retirement was not a possibility for my father then or for years after.

What became crystal clear to me was how financial illiteracy can affect stress, even when someone is otherwise literate. I wanted to make a difference. So began my pursuit of financial planning knowledge and my why���to positively impact the financial lives of as many people as possible.

Over the 30 years that followed, I went from private wealth advisor to institutional investment manager to my current role as a consultant to investment management firms. Along the way, I had a decade-long stint as adjunct faculty, lectured in more than two dozen countries and wrote often on financial matters.

Each of these experiences taught me things, and the lessons weren���t purely financial. Here are three of my greatest takeaways, which help inform my new book, Get to Work… on OUR Future:

1. Always be curious. You���ll be amazed at what you can learn. Curiosity can also free you from the pain of harsh feedback, because it���s a mindset that helps you wonder why that person said that thing that hurt.

The opposite of being curious is defensiveness. Defensiveness is your ego taking over, protecting its need to be smarter, prettier and stronger than others. You���ll be better off if you don���t allow your ego to steer you.

2. Emotional intelligence will often carry you further than the sort of intelligence that���s captured by an IQ test. Your awareness of both yourself and others can help you to be more effective. Think about a stimulus followed by your immediate response���and then think about a stimulus followed by you pausing, so you understand the impact on you before you respond. That pause is called choice.

For example, after receiving harsh feedback, that pause can take our ego off autopilot and gives us a chance to think. Is there any truth to the feedback? Could that feedback help me raise my game? Is their intent to hurt me and, if so, why���or are they more focused on making themselves look smarter?

3. If you can internalize the Buddhist definition of happiness, ���not wanting,��� you might just be able to get off life���s hedonic treadmill. Life today may not be cheap. But it needn���t be expensive to be joyful.

Michael Falk, CFA, CRC, is a partner at the Focus Consulting Group, specializing in helping wealth management teams leverage their talents. In addition to his new book, Michael is the author of��

Let���s All Learn How to Fish��� To Sustain Long-Term Economic Growth

��and co-author of��

Money, Meaning and Mindsets

. Follow him on Twitter @MSFalk.

Michael Falk, CFA, CRC, is a partner at the Focus Consulting Group, specializing in helping wealth management teams leverage their talents. In addition to his new book, Michael is the author of��

Let���s All Learn How to Fish��� To Sustain Long-Term Economic Growth

��and co-author of��

Money, Meaning and Mindsets

. Follow him on Twitter @MSFalk.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Three Life Lessons appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 17, 2019

Blessing in Disguise

IN OCTOBER, while I was visiting family in California, I got a text from an old friend, Tass. He had lost his job.

Tass and I were close buddies in college, but we lost touch. After completing our undergraduate degrees in computer science, I started working, while Tass pursued a business degree. We soon ended up in different parts of the globe. Many years later, we bumped into each other at an airport. I learned that Tass had moved abroad to start his own offshore business. We exchanged contact information, but soon lost touch again.

This past summer, Tass emailed me to say that he was moving to the city where I live. We got together soon after his arrival and spent an entire evening catching up. Tass���s startup had been a thrilling business adventure, but it had also drained his finances. He moved back to the U.S. in search of a fresh start.

Tass needed to get his finances back on track���quickly. He had his own retirement to worry about, plus college costs for two teenagers. He took a well-paid management position. But after many years of self-employment, he didn���t adjust well to the corporate world. A few stressful months later, he called it quits and returned to his software roots.

Tass brushed up on his coding skills and started chasing six-figure programming jobs. He worked mostly out of state, leaving his family for long stretches. His latest job as a senior programmer brought him to my city.

In the weeks following our reunion, I started to worry about Tass. He missed his family. I found it odd that he moved out of state just for a fatter paycheck. Tass had credible qualifications, wide-ranging experience, and a proven reputation for hard work and self-discipline. He could easily get a decent-paying job close to home. Financially, his out-of-state work made little sense. Though his pay was higher, most of the excess was offset by the cost of a second home and travel. I also wondered whether Tass took into account the higher taxes he paid on his extra earnings.

His new employer was in the middle of a merger. Tass seemed unconcerned about the possibility of restructuring and job consolidation. He was convinced his new job was secure���until he was told otherwise.

Tass was shocked. But he quickly regrouped, reworked his resume and started job hunting. When I returned from California, we met up, and I again broached the topic of whether a decent-paying job in his hometown might be better than a higher-paying job elsewhere. This time, Tass paid closer attention to the math. The net savings from his last job, after taxes and all additional expenses, was far lower than he originally thought.

By working closer to home and saving more in tax-deductible retirement accounts, he could cut his living costs and his tax bill���and increase his monthly savings. Staying home would also give him additional time for freelancing.

Within a matter of weeks, Tass got a job offer from a company in his hometown. He promptly accepted and relocated back home, to the delight of his family. I miss him���but I think, for Tass, getting laid off was a blessing in disguise.

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. His previous articles include Bonding With Bonds,��Measuring Up��and��It’ll Cost You.��Self-taught in investments, Sanjib passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. He’s passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances.

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. His previous articles include Bonding With Bonds,��Measuring Up��and��It’ll Cost You.��Self-taught in investments, Sanjib passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. He’s passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances.

Do you enjoy articles by Sanjib and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Blessing in Disguise appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 16, 2019

Death and Taxes

TAX-DEFERRED accounts are great, until they aren���t���when we have to pay taxes on our withdrawals. Millions of Americans have tax-deferred accounts, pundits laud them, companies help fund them, institutions service them and markets help them grow. But when it comes time to empty them, often the only person to guide us is Uncle Sam, who���s patiently awaiting his cut.

Efficiently managing 30 years of retirement withdrawals from a 401(k), 403(b), IRA or other tax-deferred account is just as important as the 40 years of accumulation. While we could just follow the government���s required minimum distribution (RMD) rules beginning at age 70��, who says these rules are optimal? Granted, the normal playbook is to postpone paying taxes for as long as possible. Heck, ���deferred��� is the way these accounts are described.

Yet deferring may not be right for everyone. There are some widely discussed reasons to make earlier and larger withdrawals from tax-deferred accounts���to convert this money to a Roth IRA, to avoid future tax rate increases, to use the money while still young and healthy, and to reduce future RMDs by making withdrawals earlier in our 60s, when we might be in a lower tax bracket.

Married couples have an often-overlooked additional reason to consider extra early withdrawals: Their taxes will almost certainly increase after the first spouse dies. Think of this as the widow or widower���s tax. It’s is an issue I recently discovered when I was weighing how much to withdraw from the retirement accounts owned by my wife and me.

What’s the problem? First, the standard deduction for the surviving spouse will typically decline from $24,400, the 2019 level for those married filing jointly, to $12,200 for a single individual. In addition, the surviving spouse will lose the additional ���over age 65��� deduction of $1,300 for the deceased spouse.

Assuming the same income and a 22% marginal tax rate, the surviving spouse���s tax bill will increase $2,970 from lost deductions alone. On top of this, tax rates also increase. While the change to filing as a single individual increases tax rates by only two percentage points for a large portion of middle-income surviving spouses, tax rates can jump as much as eight to 11 percentage points at certain income levels, as shown in the table below for 2019. In particular, check out the tax-rate increases for the taxable-income ranges highlighted in bold:

Married couples with annual incomes around $40,000 to $80,000, or above $160,000, are likely to get hit with significantly higher tax rates upon the first spouse���s death. Today���s tax rates are unusually low. That means the tax penalty could be even higher, depending on the results of 2020���s election. It could also be higher after 2025, when today���s low tax rates are slated to return to pre-2018���s higher levels.

How can married couples take advantage of today���s low tax rates? If their taxable income is around or only moderately above $39,500 in 2019, couples might consider additional withdrawals from tax-deferred accounts, perhaps up to a taxable income of $78,950. That���s the equivalent of $103,350 in total income, once you figure in the standard deduction. The married marginal tax rate remains a miserly 12% at these income levels. Paying taxes at this rate may allow the surviving spouse to avoid paying taxes at a much higher rate later on.

Likewise, if income is already above $160,000, couples might consider tax-deferred account withdrawals to achieve a taxable income of as much as $321,450, equal to $345,850 in total income, after factoring in the standard deduction. Even at this very high income, the marginal tax rate remains a relatively modest 24%.

Keep in mind that this additional taxable income may trigger higher taxes on your Social Security benefit or higher Medicare premiums, and perhaps both. Don���t plan to spend these extra withdrawals in the near future? The best strategy is probably to convert this money to a Roth IRA.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. ��His previous articles include Take a Break,��7,000 Days��and��Window Dressing.

John Yeigh is an engineer with an MBA in finance. He retired in 2017 after 40 years in the oil industry, where he helped negotiate financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. ��His previous articles include Take a Break,��7,000 Days��and��Window Dressing.

Do you enjoy articles by John and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Death and Taxes appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 15, 2019

Candy Land

ACCLAIMED AUTHOR Malcolm Gladwell talks about the importance of adding ���candy��� to his writing. By this, he’s referring to the asides, trivia and factoids that he uses to hold readers��� interest. Gladwell is quick to note, however, that writing can���t be all candy, with no main course, just as it can���t be all main course with no candy. To be effective, he includes both substance and entertainment.

When it comes to your investment portfolio, does the same principle apply? Is there a need for candy? If you study the literature, the answer is clear: Investments that are interesting, fun or popular tend not to be as profitable as those that are simple, cheap and mundane. Investing in��hedge funds, picking��stocks��or dabbling in��venture capital? No question, those are all interesting and fun���but the odds are also stacked against you. Boring as it sounds, most people are best served by a straightforward portfolio of low-cost index funds. That is invariably what I recommend���because that���s what the data say and also because that���s what I���ve seen work best in practice.

But is that it? Should everyone just stick with boring old index funds? Is candy strictly off limits���end of story, case closed? No, that’s too simplistic and too uncompromising. I see at least three situations in which a modest amount of candy is not only acceptable, but might also be beneficial.

1. When it builds knowledge.��I���m glad that my teenage children have shown an interest in investing. While I���ve given them the same advice I give everyone else���to keep things simple���they���ve learned far more from the individual stocks that their grandfather gave them, when they were born, than they���ve learned from owning index funds.

Among other things, they���ve learned what a public company is and what it means to be a shareholder. They���ve learned the relationship between corporate earnings and stock prices���and why that link often breaks down. As a result, they���ve also learned the value of diversification. Most important, it���s made investing interesting enough to hold their attention. Over the years, they���ve asked far more questions about McDonald���s and Smucker���s than they ever would have asked if they���d owned just an S&P 500 index fund. And the result is that they���ve learned a lot more. To be sure, they might have earned more holding a simple index fund, but I don���t think you can put a price on the education that they���ve received.

Another example: Last month, at the Thanksgiving table, a college-age relative told me about a stock she had purchased called Cronos. I asked if it was Kronos the software company, Kronos the chemicals manufacturer or Cronos the marijuana producer. Unfortunately, it was indeed the marijuana company. She told me that she had already lost 60% of her investment and asked what she should do.

While I���m sorry the investment hasn���t worked out, the silver lining is that it led to a productive conversation (and���who knows?���it may still work out). For better or worse, investment knowledge is built incrementally, often with some trial and error. In this case, it was a good opportunity to discuss why a growing company doesn���t always translate into a rising stock. Over the past nine months, Cronos’s revenue has tripled, but its losses have grown tenfold. My advice: If you have children, I���d buy a few index funds, but I���d also let them choose a few stocks.

2. When the risk-reward equation is clear.��Every investment occupies its own place on the risk spectrum. While there���s no such thing as ���guaranteed��� when it comes to investing, some investments offer a much clearer line of sight to profitability than others. Some examples: a rental property with a tenant in place or a partnership stake in a medical practice. I see these as very reasonable choices and a good way to diversify.

3. When it���s a unique opportunity.��About 15 years ago, when my friend Dan was in college, a handful of his classmates invested in a friend���s startup company. That friend? Mark Zuckerberg. Could anyone have predicted that Zuckerberg���s startup would turn into the behemoth that it has become? Unlikely. But it was clear, even then, that Facebook was unique and off to a fast start. To be sure, I don���t recommend betting on every 19-year-old with a startup, but it���s important to remember that some do succeed. If something looks truly unique, you don���t need to reflexively slam the door on it. In these cases, I think it���s okay to place a small bet.

Bottom line: In most cases, and for most people, I think it���s best to keep things simple, but it���s also important to avoid absolutes. Consider each investment on its own merits.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Owning Oddities,��Imagining the Worst��and��The Unwanted Payday

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Owning Oddities,��Imagining the Worst��and��The Unwanted Payday

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Candy Land appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 14, 2019

Low Blows

THE INDEX FUND fee-cutting battle reached its seemingly inevitable conclusion more than a year ago, when Fidelity Investments launched four zero-cost index funds. You can���t get any lower than zero, right? Apparently, you can. One small fund company is now effectively paying investors to own one of its index funds.

Still, the price war among financial companies has clearly moved on, with some firms eliminating brokerage commissions in 2019 or touting the high interest rate paid by their brokerage cash account. Cutting index-fund expenses is, it seems, so last year.

Where does that leave investors? Have they benefited from the index fund fee-cutting battle? I believe the answer is most definitely ���yes,��� though I also suspect investors haven���t benefited to the degree they imagine���for three reasons:

1. It���s all about the headlines.

The battle to offer index funds with the lowest expenses has focused on marquee categories, like S&P 500 funds, total U.S. stock market funds, total international stock funds and total U.S. bond market funds. These are the categories that offer maximum bragging rights to fund companies.

But the enthusiasm for cutting fund expenses doesn���t extend to less competitive categories. For instance, Invesco DB Agriculture Fund charges 0.89%, iShares MSCI Frontier 100 ETF 0.81%, SPDR EURO STOXX Small Cap ETF 0.46% and WisdomTree Managed Futures Strategy Fund 0.65%.

The good news is, nobody���s forced to buy these overpriced funds and, indeed, I don���t think they���re a necessary part of a globally diversified portfolio. Instead, most of us would do well either to stick with the big three���a total U.S. stock market fund, a total international fund and a total U.S. bond market fund���or to opt for the radical simplicity offered by a target-date retirement fund built around index funds.

2. Costs don���t always drive performance.

When you buy an index fund, it���s reasonable to expect you���ll earn the target index���s annual return, minus whatever the fund charges in expenses each year. To be sure, there are other variables, such as money earned from securities lending or money lost to trading costs. Still, in theory, annual expenses should be the biggest driver of a fund���s performance relative to its underlying index.

But is that the case? Consider the zero-cost index funds launched by Fidelity. Instead of tracking well-known indexes, the four funds mirror indexes created by Fidelity itself. That step was presumably taken to avoid paying a licensing fee to, say, MSCI or S&P Dow Jones, thus reducing Fidelity���s loss on each fund (if Fidelity is indeed losing money, once the profit from securities lending is figured in).

This ���tracking your own index��� arrangement strikes me as a little suspect���sort of like getting schoolkids to grade their own tests. Still, on its site, Fidelity publishes the performance of the underlying indexes, so you can see whether the funds are doing a decent job of tracking their benchmark. At first blush, you might expect the funds to mirror those indexes almost exactly, given that the funds aren���t charging expenses.

But things haven���t quite worked out that way. Yes, since inception, Fidelity���s ZERO Large Cap Index Fund and ZERO Total Market Index Fund have tracked their benchmarks fairly closely. But the ZERO Extended Market Index Fund is way ahead of its benchmark, while the ZERO International Index Fund is well behind.

What gives? When tracking indexes that contain a large number of securities or contain securities that are difficult to buy in large quantities, funds often don���t purchase all the securities involved. Instead, they use sampling techniques���and sometimes the sample isn���t very good.

My advice: Before you buy an index fund, check out its tracking error versus the underlying index. Even if the tracking error has benefited investors in the past, don���t take comfort in that���because there���s a good chance that one day it���ll work to shareholders��� detriment.

3. Tiny advantages are easily squandered.

Suppose you���re in the market for a total bond market index fund. You might choose one of the offerings from major index-fund providers like Charles Schwab, Fidelity, iShares, SPDR or Vanguard Group. Note that Vanguard offers a conventional mutual fund, as well as an exchange-traded fund that���s slightly cheaper.

The annual expenses range from Fidelity���s 0.025% to the 0.05% charged by both the iShares ETF and the Vanguard mutual fund���a difference of 0.025 percentage point, equal to $2.50 a year on a $10,000 investment. That $2.50 wouldn���t even buy you a ride on the New York City subway.

I���m not suggesting you ignore such differences in annual expenses. But let���s be honest: The savings are tiny compared to other costs you might incur. Suppose you���re trying to decide whether to buy your bond market mutual fund from Fidelity or Vanguard. On $10,000, Fidelity���s offering will save you $2.50 a year.

But let���s say you���re also planning to keep another $10,000 in the default account used for uninvested cash. Recently, Vanguard Federal Money Market Fund was yielding 1.58%, while Fidelity Government Money Market Fund was yielding 1.29%. Result? Having your $10,000 in cash at Vanguard, rather than Fidelity, might earn you an extra $29 in income over the course of a year���far offsetting the slightly higher cost on Vanguard���s bond market fund. I���m not trying to pick on Fidelity here. Its brokerage cash account offers a generous yield compared to other firms, such as Schwab.

The reality: There are so many ways to squander the cost advantage offered by low-fee index funds. You might trade too much, thereby triggering capital gains taxes and incurring transaction costs. You might keep your taxable bonds in a taxable account, rather than a retirement account, thus ending up with a tax-inefficient portfolio.

Alternatively, suppose you put just 20% of your portfolio in actively managed funds costing 1% a year. That would raise your portfolio���s average annual expenses by 0.2 percentage point���easily swamping the savings from favoring the lowest-cost index funds.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Saving Myself,��Breaking Bad��and��Bullheaded

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Saving Myself,��Breaking Bad��and��Bullheaded

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Low Blows appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 13, 2019

Good for You?

IS SUSTAINABLE investing a fad? Everyone seems to be talking about it���not least product providers eager to persuade us that their sustainable funds are so much better, more ethical or more likely to outperform than everyone else���s.

Leaving aside the moral reasons for investing in funds that aim to deliver environmental and societal benefits, is sustainable investing a good idea financially? Do sustainable funds, otherwise known as ESG (environmental, social and governance) funds, deliver higher investment returns than their mainstream counterparts? What does the evidence tell us?

The first question to ask: Is there any reason high-sustainability companies should produce higher returns than low-sustainability firms? A study��published in 2014 analyzed data from 180 of the largest U.S. companies between 1993 and 2010. The researchers concluded that high-sustainability companies ���significantly outperform their counterparts over the long-term, both in terms of stock market as well as accounting performance.���

The authors of a German study published in 2015 reached a similar conclusion. Aggregating information from more than 2,000 studies, they found that ���the business case for ESG investing is empirically very well founded.��� They also showed how the positive correlation of high ESG scores and corporate financial performance appears stable over time, and manifests itself across different sectors and regions.

So far, then, the evidence is encouraging. High-sustainability companies tend to perform better. In theory, those who invest in them can expect higher financial returns.

There is, however, another side to the story. In a study published in 2009, Harrison Hong and Marcin Kacperczyk made a strong case for doing the exact opposite and investing instead in so-called sin stocks. There was, they suggested, a ���societal norm��� against, say, gambling companies and producers of alcoholic drinks and tobacco. As a result, they showed, such stocks are less likely to appeal to norm-constrained institutions like pension funds and thus their prices are relatively depressed. Lower valuations, of course, mean higher expected returns.

Investment author Larry Swedroe argues investors are better off investing in the whole market���including sin stocks���using low-cost index funds. He recently looked at three popular ESG indexes managed by MSCI. In each case, the ESG index had underperformed its mainstream equivalent since inception. What���s more, each of the mainstream indexes had a higher Sharpe ratio, meaning they also took slightly less risk.

But index providers use different selection criteria, and what���s true for one provider isn���t necessarily true for another. Recently, Ben Leale-Green from S&P Dow Jones Indices compared the performance of the S&P 500 Index with its ESG equivalent. Between May 2010 and July 2019, the excess return over the risk-free rate for the S&P 500 ESG Index was slightly higher than it was for the S&P 500. The annualized volatility of the S&P 500 ESG Index was also slightly lower.

Another major financial institution that advocates sustainable investing is Morningstar. Three years ago, it produced research which concluded that ���the idea that sustainable investing is a recipe for underperformance is a��myth.���

Keep in mind that sustainable investing is still relatively new, and we don���t have nearly as much historical data as we do for mainstream investing. That said, the evidence so far suggests that, if there is a performance penalty for sustainable investing, it���s a very small one.

As always, the most important thing to focus on when choosing a fund is cost. Simply put, the less you pay, the more you keep for yourself. Check out sustainable funds that are passively managed, such as iShares ESG MSCI USA ETF, iShares ESG MSCI EAFE ETF and Vanguard FTSE Social Index Fund. Active management is a zero-sum game before costs, and a negative-sum game after costs. The average sustainable investor using active funds must underperform the average investor using passive funds. It���s simple arithmetic.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He’s a campaigner for positive change in global investing,��advocating better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of��The Evidence-Based Investor, which is where a version of this article first appeared. His previous articles for HumbleDollar include Better Than Timing,��Writing Wrongs��and��Private Matters.��Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.

Robin Powell is an award-winning journalist. He’s a campaigner for positive change in global investing,��advocating better investor education and greater transparency. Robin is the editor of��The Evidence-Based Investor, which is where a version of this article first appeared. His previous articles for HumbleDollar include Better Than Timing,��Writing Wrongs��and��Private Matters.��Follow Robin on Twitter @RobinJPowell.

Do you enjoy articles by Robin and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Good for You? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

December 12, 2019

Durn Furriners

A BURNING QUESTION has only gotten hotter as foreign stocks have lagged disastrously over the past dozen years: Should any of your stock market money be overseas?

Most experts say ���yes.��� Vanguard Group, for one, recommends investors allocate 40% of their stock investments to foreign markets. In fact, some pundits have smugly derided what they call the ���home bias��� of those U.S. investors who avoid or underweight foreign stocks. Those stocks currently make up about 45% of world market capitalization.

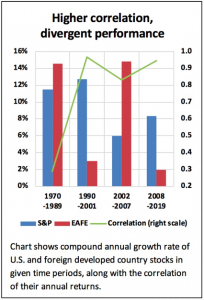

That smugness has waned considerably since 2007, as the S&P 500 Index has delivered a compound annual growth rate of 8%, versus 2% for MSCI���s Europe, Australasia and Far East (EAFE) index of developed country stocks. That���s a lot of opportunity cost.

If emerging markets were included, the picture would look even worse. Vanguard Emerging Markets Index Fund is up a cumulative 10% over the past 12 years, compared with 29% for EAFE and 163% for the S&P 500. For this article and in the accompanying chart, I compare the S&P 500 and EAFE. The latter index goes back to 1970. By contrast, emerging markets indexes are relatively new, so it���s hard to do long-term comparisons.

The data in the chart suggests investors can���t expect a ���free lunch��� by diversifying into foreign stocks. That phrase was used by Harry Markowitz, who introduced Modern Portfolio Theory in 1952. According to MPT, combining assets with similar long-term return potential but low correlations can boost portfolio returns while reducing volatility. Trouble is, foreign stocks have offered neither low correlations nor comparable returns for 12 years���and they didn���t in the 1990s, either.

The data in the chart suggests investors can���t expect a ���free lunch��� by diversifying into foreign stocks. That phrase was used by Harry Markowitz, who introduced Modern Portfolio Theory in 1952. According to MPT, combining assets with similar long-term return potential but low correlations can boost portfolio returns while reducing volatility. Trouble is, foreign stocks have offered neither low correlations nor comparable returns for 12 years���and they didn���t in the 1990s, either.

The only sustained period of foreign outperformance since 1989 was in 2002-07. Since the EAFE index���s inception in 1970, the S&P 500���s cumulative return has been double that of EAFE.

But don���t write off foreign stocks just yet.

Take a look at the chart. While annual correlations since 1989 have risen to close to 1���the point at which two assets move perfectly in the same direction at the same time���U.S. and foreign stock performance has diverged widely in each of the three distinct cycles. They���re moving in the same direction most years, but one usually goes much further than the other over longer periods.

The collapse of the Japanese asset bubble dragged down EAFE���s return during Japan���s ���Lost Decade��� of the 1990s. Indeed, at the market low of 2009, the Nikkei 225 index of Japanese stocks was down more than 80% from its 1989 peak 20 years earlier.

There���s a lesson for us there.

You remember how unbeatable we thought Japan Inc. was? (Okay, I���m showing my age.) Pop stars sang that they were ���turning Japanese��� and politicians said the U.S. needed to emulate Japan���s industrial policy. Imagine how invulnerable Japanese investors must have felt in the 1980s as they bought up U.S. real estate with inflated stock market gains and with money from their trade surplus with America. Now, think about the fortunes that subsequently were lost by Japanese investors with a strong home bias, as the Nikkei sank while other markets soared.

Could a similar long-term unwinding of inflated valuations and expectations, coupled with economic policy errors, happen in the U.S.? Of course.

While many U.S. investors still buy into the emerging markets story, we���re tempted to think America will forever lap what we see as senescent European and Japanese markets. How exactly could their economies and financial markets ever beat ours again? What���s the story, what���s the catalyst?

The point is, we don���t know and we can���t know. Frankly, the emerging markets story is full of holes, too. A strong argument for diversification: It���s a defense against the unknown���a way to guard against our own hubris when we start to feel confident.

No one can tell you whether foreign stocks will enhance your portfolio going forward. Still, expectations and valuations for overseas markets are relatively low���which is one reason they could trounce U.S. stocks in some multiyear period in the future, as they have in the past.

My suggestion: Set a target percentage allocation for foreign stocks and thereafter regularly rebalance���perhaps annually, every two years or when they move some trigger amount from your target percentage. That way, you take your own emotions, expectations and predictions out of the decision.

What about my own portfolio? Don���t take this as a recommendation, but several years ago I set my target overseas allocation at 38% of my stock investments, with a significant stake in submerging���I mean emerging���markets. I was positioning for a rebound that hasn���t happened yet, and trying to follow expert asset allocation advice. Many a time I���ve been tempted to reduce my stake, but I���ve stuck to it, figuring that any decision I make based on disappointment with past performance likely will be the wrong one.

Forget about betting on the best investment, ignore pundits��� predictions and guru allocations, and���above all���curb your own enthusiasm. Instead, think of diversifying overseas as hedging your bets.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. Bill’s previous articles for HumbleDollar include Oldies but Goodies,��Mild Salsa��and��Weight Problem. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart.

HumbleDollar makes money in four ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense, sell merchandise and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other items, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Durn Furriners appeared first on HumbleDollar.