Jason Micheli's Blog, page 79

April 11, 2023

The Expected is as Yet Inconceivable

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Georges Florovsky was a twentieth century Russian Orthodox theologian who taught at Princeton near the end of his career.

In a beautiful way, he mines the scriptures and the tradition to express the mystery and the hope given to us in the “pledge” that is the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. I thought I’d add a few eggs to your Easter basket by sharing his meditation on the Gospel of Resurrection along with some clarifying comments from yours truly.

Florovsky begins by making the always helpful and counter-cultural point that, according to the scriptures, death is not natural.

Florovsky writes:

“Death is a catastrophe for humanity.

This is the basic principle of the whole of Christian anthropology.

Man is an amphibious being, both spiritual and corporeal, and so he was created by God. Body belongs organically to the unity of human existence. And this was perhaps the most striking novelty in the original Christian message.”

Remember, the gospel which the primal church took into the world was firstly news not of the crucifixion but of the resurrection— the former is only redemptive in light of the latter. As much as the word of the cross, however, the Gospel of Resurrection was absurd and ghastly to a world shaped by the Greek religion of Plato.

Florovsky makes this explicit:

“The preaching of the Resurrection as well as the preaching of the Cross was foolishness and a stumbling—block to Gentiles.

St. Paul had already been called a “babbler” by the Athenian philosophers just “because he proclaimed to them Jesus and the resurrection.”

The Greek mind was always rather disgusted by the body.The attitude of an average Greek in early Christian times was strongly influenced by Platonic ideas, and it was a common opinion that the body was a kind of a “prison,” in which the fallen soul was incarcerated and confined. The Greeks dreamt rather of a complete and final dis-incarnation.”

The Gospel of Resurrection, in other words, was more than a stumbling block to pagans. It was deeply unsettling. It sounded to them like the opposite of good news.

“The Christian belief in a coming Resurrection could only confuse and frighten the Gentile mind.It meant simply that the prison will be everlasting, that the imprisonment will be renewed again and for ever. The expectation of a bodily resurrection would befit rather an earthworm suggested the Roman antagonist of the Church, Celsus, and he jeered in the name of common sense. He nicknamed Christians a “flesh-loving crew.”

With all Greek philosophers the fear of impurity was much stronger than the dread of sin. Indeed, sin to them just meant impurity. Evil comes from pollution, not from the perversion of the will. One must be liberated and cleansed from this filth.

And at this point Christianity brings a new conception of the body as well. From the very beginning Docetism was rejected as the most destructive of temptations, a sort of dark anti–gospel, proceeding from the Anti–Christ (I John 4.2–3). And St. Paul emphatically preaches “the redemption of our body” (Romans 8.23).

St. John Chrysostom commented:

“Paul deals a death-blow here to those who depreciate the physical nature and revile our flesh. It is not flesh, as he would say, that we put off from ourselves, but corruption. the body is one thing, corruption is another. True, the body is corrupt, but it is not corruption. The body dies, but it is not death. The body is the work of God, but death and corruption entered in by sin. Therefore, he says, I would put off from myself that strange thing which is not proper to me. And that strange thing is not the body, but corruption.”

The point he’s making, the hope he’s clarifying is that the future resurrected life shatters and abolishes not the body, but that which clings to it, corruption and death.

This is the simile used by St. Paul. “So also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown in corruption: it is raised in incorruption” (I Corinthians 15.42).

The earth, as it were, is sown with human ashes in order that it may bring forth fruit, by the power of God, on the Great Day.

Florovsky continues:

“Like seed cast on the earth, we do not perish when we die, but having been sown, we rise” (St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation).

Each grave is already a shrine of incorruption.

The resurrection, however, is no mere return or repetition. The Christian dogma of the General Resurrection is not that eternal return which was professed by the Stoics. The resurrection is the true renewal, the transfiguration, the reformation of the whole creation. Not just a return of what had passed away, but a heightening, a fulfillment of something better and more perfect: “And that which thou sowest, thou sowest not that body which shall be, but bare grain… It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body” (1 Corinthians 15.37, 44).

Resurrection is not resuscitation, neither for Jesus nor for us.

Resurrection does not mean Jesus’s life simply starts up again.

Nor will it so mean for us.

A profound change will take place.

And yet the individual identity will be preserved.

Florovsky elaborates:

St. Paul’s distinction between the “natural” body and the “spiritual” body obviously calls for a further interpretation. And probably we have to collate it with another distinction he makes in Philippians 3.2: the body “of our humiliation and the body of His glory.” Yet the mystery passes our knowledge and imagination: “It has not yet appeared what we shall be” (I John 3.2). But as it is, Christ has risen from the dead, the first–fruits of those who have fallen asleep (I Corinthians 15.20).

The Lord’s flesh does not suffer corruption, for it abides in the very bosom of the Life, in the Hypostasis of the Word, Who is Life. And in this incorruption, the Body has been transfigured into a state of glory. The body of humiliation has been buried, and the body of the glory rose from the grave.

In the death of Jesus the powerlessness of death over Him was revealed. In the fullness of His human nature Our Lord was mortal. And He actually died. Yet death did not hold Him. “It was not possible that He should be holden of it,” (Acts 2.24) As St. John Chrysostom puts it, “death itself in holding Him pangs as in travail, and was sore beset…, and He so rose as never to die.”

He is Life Everlasting, and by the very fact of His death He destroys death. The whole fabric of human nature in Christ proved to be stable and strong. The disembodiment of the soul was not consummated into a rupture.

Even in common death of man, as St. Gregory of Nyssa pointed out, the separation of soul and body is never absolute, a certain connection is still there.

In the death of Christ this connection proved to be not only a “connection of knowledge”: His soul never ceased to be the “vital power” of the body. Thus this death in all its reality, as a true separation and disembodiment, was rather like a sleep.

“Then was man’s death shown to be but a sleep” as St. John of Damascus says.

The reality of death is not yet abolished, but its powerlessness is now revealed. The Lord really and truly died. But in Jesus’s death the power of the resurrection was manifest, which is now latent in every death.

Your death is certain, yet because of Jesus’s death, it’s just as certain that the power of Easter is already latent in your death.

“In the body of the Incarnate One the interim between death and resurrection is foreshortened. “It is sown in dishonor: it is raised in glory: it is sown in weakness: it is raised in power; it is sown a natural body: it is raised a spiritual body” (I Corinthians 15.43–44). In the death of the Incarnate One this mysterious growth of the seed was consummated in three days: Triduum mortis.

The Lord rises from the dead, as a Bridegroom comes forth from the chamber. This was accomplished by the power of God, as also the General Resurrection will in the last day be accomplished by the power of God. And in the Resurrection the Incarnation is completed and consummated a victorious manifestation of Life within human nature, a grafting of immortality into the human composition.”

The Resurrection of Christ was a victory not over his death only, but over death in general.

The hopelessness of dying has been abolished

“In His resurrection the whole of humanity, all human nature, is co-resurrected with Him: “the human race is clothed in incorruption.”

Co-resurrected — not indeed in the sense that all are actually raised from the grave: men do still die.”

St. Paul is emphatic on this point.

The resurrection of Christ would become meaningless if it were not a universal accomplishment. And faith in Christ itself would lose any sense and become empty and vain. If Christ’s resurrection is not a harbinger of the resurrection of all, there would be nothing to believe in.

“As Athanasius says, “Corruption ceasing and being put away by the grace of Resurrection, we are henceforth dissolved for a time only, according to our bodies’ mortal nature; like seeds cast into the earth, we do not perish, but sown in the earth we shall rise again, death being brought to nought by the grace of the Savior” (On the Incarnation).

All will rise. From henceforth every disembodiment is but temporary. The dark vale of Hades is abolished by the power of the life-giving Cross. St. Gregory of Nyssa strongly stresses time organic interdependence of the Cross and the Resurrection: “For as the principle of death took its rise in one person and passed on in succession through the whole of human kind, in like manner the principle of the Resurrection extends from one person to the whole of humanity… For when, in that concrete humanity which He had taken to Himself, the soul after the dissolution returned to the body, then this uniting of the several portions passes, as by a new principle, in equal force upon the whole human race. This then is the mystery of God’s plan with regard to His death and His resurrection from the dead.”

In other words, Christ’s resurrection is a restoration of the fullness and wholeness of human existence, a re-creation of the whole human race, a “new creation.” St. Gregory follows here faithfully in the steps of St. Paul. There is the same contrast and parallelism of the two Adams. The General Resurrection is the consummation of the Resurrection of Our Lord, the consummation of His victory over death and corruption. And beyond the historical time there will be the future Kingdom, “the life of the age to come.” Then, at the close, for the whole creation the “Blessed Sabbath,” the very “day of rest,” the mysterious “Seventh day of Creation,” will be inaugurated for ever.

The expected is as yet inconceivable.

But the pledge is given.

Christ is risen.”

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 10, 2023

Transfiguring Being

Happy Easter!

Here’s our final session with Chris Green on his book, Being Transfigured.

Our next series of Monday night sessions will begin 4/24 on Tony Robinson’s book, What’s Theology Got To Do With It.

You can sign up to participate or receive the recordings HERE.

Here’s a citation from Maximus the Confessor from Chris’s chapter that I think summarizes the session well:

This is the mystery which circumscribes all the ages, and which reveals the grand plan of God, a super-infinite plan infinitely pre-existing the ages an infinite number of times. The essential Word of God became a messenger of this plan when He became man, and, if I may rightly say so, revealed Himself as the innermost depth of the Father’s goodness while also displaying in Himself the very goal for which creatures manifestly received the beginning of their existence. And this is because it is for the sake of Christ—that is, for the whole mystery of Christ—that all the ages and the beings existing within those ages received their beginning and end in Christ.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 9, 2023

The Space Between the Angels

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

John 20.1-18

Christ is Risen!

Christ is Risen indeed!

Alleluia!

The Lord Jesus is Risen indeed; however, lest we forget, Christ was not raised from attending a wedding in Cana. Nor was Jesus raised while throwing his temple tantrum or while sipping bourbon with sinners. Jesus was raised from corruption in the tomb, having first been inflicted a manner of death so ghastly the word crux was verboten in polite pagan society.

The context is critical for Easter’s intelligibility. Just so, in the ancient tradition of the church, Easter is inextricable from its antecedent events. Easter gets its coherence by of its continuity with Holy Saturday, when the God-who-is-human is dead in the tomb, and with Good Friday, when he is betrayed, condemned, and crucified. Historically, the Paschal Feast is called the Great Three Days, the days being undetachable from one another.

Thus, properly speaking, Easter begins in the dark between Thursday night and Friday morning, in the gloaming hours after Passover, when Caiphas’s municipal guard bring the bound and bleeding Jesus from Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives to the jail cell in the chief priest’s basement. The prison cell itself is a pit carved out of bedrock, about twenty-five feet deep. Just outside the chief priest’s palace is the exact spot where Peter stands by a charcoal fire and says, “Jesus? Jesus of Nazareth, you say? Never heard of him.”

The Gospels report that Jesus prays the twenty-second psalm from his cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” The Gospels tells us Jesus prays Psalm 22, but I wonder if Jesus also prays eighty-eighth psalm while held in the dark stone hole of Caiphas’s basement:

“O lord God of my salvation, my soul is full of troubles: and my life draweth nigh unto the grave as I am counted with them that go down into the pit…”

In the first Gospel, Christ’s cry of dereliction is the only word he utters from the cross. As if, in the end, all that Jesus has to say from the cross is all we can say about the crucified Jesus: the God-who-is human has been forsaken.

Forsaken by the satanic marriage between Religion Inc. and Politics.

Forsaken by Pilate and the people of Abraham.

Forsaken by his friends.

Forsaken by us.

On Good Friday, the God-who-is human is forsaken. And no angel of the Lord appears to stay the blade in our hand. We did did not spare the Father’s only beloved Son. The Living God has an executioner. Such that, on Saturday, the Second Person of the Trinity is dead.

For the evening of Holy Saturday, as part of the ancient liturgy for the Easter Vigil, the church traditionally reads the Akedah, the story of the Binding of Isaac as found in the Book of Genesis:

“Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt-offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.”

The primal church found the parallels between the Virgin Mary’s child and the unlikely son of the elderly Abraham and Sarah auspicious. But if Mary’s boy is Isaac in the scriptural analogy, the Father Almighty is not Father Abraham.

The one whom Jesus called Abba is not akin to Abraham. Jesus’s Father is not the one who binds his Son and nails him to a tree. We do. Thus, on Good Friday, a short walk from Mt. Moriah, where Abraham took his son Isaac to murder him to honor the Lord, we push the true God up a hill called Golgotha, carrying not a blade and wood for a fire but a hammer and nails. Golgotha is Mount Moriah without the ram in the bush or the angel rushing in to the rescue. Calvary is where the children of Abraham provide the innocent lamb for slaughter, another Father’s Son.

Good Friday is Abraham going through with it.

My God, my God, why do we forsake him?

The primal church found in the story of Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac a parallel to our sacrifice of the Father’s only begotten Son, which means it’s an analogy that applies to Easter Sunday as much as to Good Friday.

The Isaac story imaginatively opens up the Easter story.So imagine.

Imagine that Abraham went through with the deed on Mt. Moriah.

Imagine he did it. Imagine Abraham closing his eyes and raising his arm and plunging the knife. Imagine his son Isaac’s scream and the silence that would follow it, save for the bleating of a lost and forgotten ram hidden amid the bushes.

Imagine Abraham making his three day trek down the mountain path back to Isaac’s mother. Imagine a stranger approaching Abraham’s campfire that first night. And, in the comfortable anonymity of the darkness, imagine Abraham confesses to this stranger his story about what he had believed god required, how it led him to violence and murder, how in his grief he knew now that heaven wept with him, how he had been blind and deaf, how his religious zeal really had been unfaith, how as he plunged the knife he realized he had confused the true God with his Adversary. Imagine Abraham spilling out his guilt and shame, and then realizing he’d not even asked for the stranger’s name.

“Tell me your name,” Abraham asks.

And the stranger lifts up his bowed head and pulls back his hood and replies, “Isaac. My name is Isaac.”

And then imagine Isaac showing Abraham his hands and his side.

He is Risen.

Isaac can help us begin to grasp the merciful surprise of Easter.

Peter thrice denied Jesus. Only Judas betrayed Jesus for spending money but none of Jesus’s friends attempted to buy his release. Mary Magdalene and John the Beloved Disciple, they did not shout, “Crucify him!” Yet neither did they shout,“Do NOT crucify him!”

All failed him.

But on the third day, “Isaac. My name is Isaac.”

The one whose side we pierced returns with an assurance of absolution. The one whom we forsook comes back with forgiveness. The Man of Sorrows we mocked on the cross is restored from it as once again the Man for Others.

Yet this surprising mercy— what the church calls grace— is not itself the mystery of Easter nor is it by itself the promise of Resurrection.

Forgiveness alone does not go far enough in expressing the hope of the Gospel which the scriptures give us.

The mystery of Easter is yet more incompressible. The promise of Resurrection is so surpassingly better than a merciful surprise.

The promise of Resurrection is so good you do not yet have a desire for it.The mystery of Easter, the promise of Resurrection— it is here in our Gospel, hiding in plain sight. You can glimpse it if you defamiliarize yourself with the scripture and allow it to become strange again. Like Mary Magdalene, you must bend down to peer inside. That is to say, you cannot see it by standing as you’ve always stood.

Notice the all important detail John reports for you: the empty tomb isn’t.

Notice the all important detail John reports for you: the empty tomb isn’t.The tomb is not empty!

Mary, John reports, stoops down to look into the tomb and inside the tomb sit what? Two angels. And— again the detail is everything— the first angel sits where? At the head of Christ’s grave slab. And the second angel sits where? At the foot of Jesus’s grave slab.

Thus, not only is the tomb not empty. It’s no longer a tomb.It’s a throne.This is plainly visible to anyone familiar with the scriptures.

In the Book of Exodus, after the Lord rescues the Israelites through the Red Sea, the Lord journeys through the wilderness with his people, sheltered in the Mishkan, the tabernacle, and seated invisibly upon the Kapōreṯ, the mercy seat, the throne flanked at the head and the foot by two cherubim angels. This is the selfsame throne which resided in the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem temple.

Throughout the scriptures, the cherubim flanking the ark, above and below, mark the spot where the Living God is locatable.

The true God, who himself cannot be seen, dwells in the space between the two cherubim.

To “see” the unseeable God is to gaze upon the space between the angels.

Not to see God here is to behold him enthroned in glory.

The tomb is not empty nor is it any longer a tomb.

It’s a throne.

Moreover, the space between the angels, in the tabernacle and the temple, is a throne always meant for the Son of Man. Nearly six centuries before Mary gives birth to Jesus, God gives the priest Ezekiel a vision as the context for his call to prophecy. God shows Ezekiel a heavenly prototype of the cherubim throne; that is, a vision of how the throne of God appears eternally.

And what does Ezekiel see?Seated on the throne, charged with the glory that constitutes the throne, with an angel at his head and an angel at his feet, Ezekiel sees “a figure who has the appearance of a man.”The man on the throne of God who shines with God’s own glory, who is God’s glory, is Jesus. The disciples on the Mount of Transfiguration simply caught a glimpse of who Jesus has always been in the Trinity. Five hundred and seventy years before Jesus is born Ezekiel sees what John shows you today, the Risen Jesus enthroned in the space between the angels.

He died between two thieves.

He’s been raised up and enthroned between two angels.

Easter is more mysterious than simply a merciful surprise.

The empty tomb is no longer a tomb. Nor is the tomb empty. The tomb is full.

The apparent emptiness signifies not the absence of the dead Jesus. The apparent emptiness signifies the presence of the body of the Risen Christ.Notice the detail John gives you.

First, Mary faces the tomb and addresses the angels, “They have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him.” Next, verse fourteen, John tells you that Mary turns. Her back is to the tomb now. And Mary “sees” Jesus but she doesn’t recognize him as Jesus. Supposing him to be the gardener, she says to the man in front of her, “Sir, if you have taken him away, tell me where you have laid him, and I will take him away.”

And then— pay attention, John reports in verse sixteen that Jesus says to her, “Mary.”

And Mary turns, John says.

She turns in the direction of his voice.

She turns towards the tomb so that her back is again to the man she took for the gardener.

Mary’s facing the tomb when she says, “Rabboni! Teacher!”She’s talking to the tomb. No, she’s talking to one enthroned there.

And it’s from that same direction that the voice of the Risen Christ corrects her. “Do not cling to me,” the Risen Jesus chastens her.

But again, notice— John hasn’t said a word about Mary grasping anyone. Rather, she’s facing the space between the angels and addressing him as “Teacher,” and he replies, “Do not cling to me.”

Which is to say:

“I am not who you have known me to be. I am more than you have known me to be. I am free of even your memories of me.”

And then Mary turns again and she runs. And she tells the disciples, no longer calling him “my lord,” (as though she could possess him) but “The Lord.” And what she tells them about him is so mysterious, so unsettling, so incomprehensible that they hide.

The tomb is not empty.It’s full.

The resurrection is not Jesus’s life starting up again.

The resurrection is not the happy ending to his story.

The resurrection is not one more thing that happened to Jesus.

And the resurrected body of Jesus is not simply his amino acids rekindling.

No, the mystery is deeper.

Again, the scriptures make this matter plain. The First Adam, the Bible says, was a living being, a mortal, material body. The Second Adam, the Bible says, became a life-giving spirit. In other words, the resurrected body of Jesus Christ is a life-giving spirt.

The resurrection is not Jesus’s life starting up again.The mystery is deeper, wordlessly greater than we imagine.Easter is the first fruit, scripture says, of God’s unfolding work, through this life-giving spirit who is the Risen Christ.

Easter is the first fruit of God’s work “to be all in all,” to fill all good things with his infinite life just as he fills the empty tomb or overwhelms the burning bush without consuming it.

Easter is not about all things living again as though everything will be as Lazarus. Easter is about all things living with the life of God.Easter is the beginning of something altogether new. Easter is a mystery so new it s deeply unsettling to all its witnesses in the Gospels. Easter is a promise so good we have neither the desire to want it nor the capacity to comprehend it. And so we reduce the promise of Easter to being reunited with our lost loved ones— a good that is still not good enough to name the promise rightly.

About ten years ago, a woman in my congregation asked to meet with me. Diane sat across from me one morning in my office. I knew her from classes I’d taught, pleasantries in the line after service, and a few hospital visits to her spouse, but I didn’t know her.

“Since we’ve decided to make this our church home, I thought you should know my story,” she told me, rubbing her hands along the channels of her corduroy skirt over and over again.

Her voice was taut with anxiety or shame. I didn’t say anything. I just waited. What he told me surprised me. It wasn’t the sort of story you hear everyday.

With long pauses and double-backs and tears— lots of weeping— she told me how a few years earlier she’d been driving home from the grocery store in the middle of the afternoon on Route One in Alexandria. Out of nowhere a pedestrian stepped into the street. Diane hadn’t been drinking. She hadn’t been distracted. She wasn’t texting or talking.

“There just wasn’t enough damn time!” She said with such force it was clear that she— not me— was the one she was trying to convince.

What she told me next surprised me even more. Diane told me how her mind developed a split personality to cope with the trauma of having killed another person. She spent nearly a year, she said, hospitalized for schizophrenia. She told me how worshipping at a new church, where folks didn’t know her and didn’t stare at the floor whenever they saw her, was one of the goals she’d set for herself upon her discharge. She wept for a long time. I had to get up, leave my office, and go hunting for more tissues. When I returned and sat down across from her, she said, “I know Jesus forgives me, but Jason, honestly, forgiveness doesn’t seem to go far enough.”

“It doesn’t go far enough,” I responded, “Sure, you’re forgiven for Christ’s sake. But that’s not the promise. The promise isn’t simply the forgiving of all wrongs, done or suffered. The promise is that your past is as unfinished for God as your future; such that, without violating who you are, Diane— your car never struck that man that morning and your mind never split.”

And she looked up from her damp tissue and I could tell she didn’t get it.

“But I did hit that man with my car,” she said and blew her nose, “and my mind did split.”

And I thought of what the apostle says about how it has not yet entered the heart of human beings to imagine what God has prepared for those who love him.

“You’re a reader,” I said to Diane, “it’s like Tolkien put it:

“One day all sad things will come untrue.”

No, that was good enough for Diane but that’s not good enough today.

That’s the Lord of the Rings. That’s not the Bible.

The promise of the resurrection is:

“One day all sad things will be made untrue through the life-giving spirit that is the body of the Risen Christ.”

The promise of the resurrection is not all things living again, as though all things will be like Lazarus.

The promise of the resurrection is all things living in the life of God.

Easter is the first fruit of God’s work to be ALL in all things.

Which is nothing less than the unmaking of all bad and evil things.

The promise is that God is at work in Jesus Christ to heal your whole timeline, to mend everything that is broken, every wrong you’ve wreaked, every sin you’ve suffered— without undoing you, all of it will be undone. That’s the hope of the Resurrection.

Resurrection will happen not just to dead bodies but to all things, not just in the future but backwards, to all of time— all of time will be transfigured so that all things will be as full with the glory of God as the tomb that is not empty. Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 8, 2023

That All Sad Things will be Made Untrue

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“And having said this,” Luke concluded for us last night, “Jesus breathed his last.” Or, as the King James Version puts it,“Having said thus, Jesus gave up the ghost.”

Just as it sounds odd to hear that in her belly Mary bore the Maker of Heaven and Earth, the inconceivability should linger with us over Holy Saturday.

The God-who-is-human had an able executioner.He is dead.“What was Jesus doing when he was dead?” some will wonder, too shy to take the simple truth of today with an open hand.

Answer: Nothing.

Jesus wasn’t doing anything while he was dead. He was dead. His story ended at Golgotha on Good Friday, the dead leader of a movement with no followers. On Saturday, the God-who-is-human is every bit as dead as you will be dead one day. His death was final, conclusive, definitive—as yours will be, and mine.

John tells us at the beginning of his Gospel that no one can see the Father apart from the Son, which means when Jesus is dead, the second person of the Trinity is as good as gone.

Jesus told us that he alone is the way, the truth, and the life— that no one can come to the Father except by the Son— but his way led him to a cross. His way had been done away by the way of the world.

God is dead.

Elected over Barabbas, Jesus became the persecuted for righteousness’s sake. Giving up his spirit, Jesus became the poor in spirit. Dying on a cross, Jesus became the beatitudes.

The beatitudes are Jesus, the God-who-is-human.And we are the antitheses.In all our theologizing about the story, we conveniently forget— Judaism was a shining light in the ancient world, offering not only a visible testimony to God who made the heavens and the earth, but a way of life that promised order and stability and well-being of the neighbor. And in a world threatened by anarchy and barbarism, the Roman empire brought peace and unity to a frightening and chaotic world. The people who got Jesus to give up the ghost— Pilate and his soldiers, the chief priests and the Passover pilgrims gathered in Jerusalem— they were all from the best of society, not the worst. And they were all doing what they were appointed to do. What they thought they had to do. What they thought was necessary for the public good.

Even the chief priests’s reasoning, if we admit it, is right: “It’s better for one man to die than for all to die...”

That’s a perfectly rational position.

It’s the position around which we’ve ordered the way of the world.

The theologians give explanations: that Jesus had to die in order for God to be gracious, that Jesus had to die in order for God to forgive us of our sin, that Jesus had to die to pay a debt we owed, but could not pay ourselves. But, in the end, what the Gospels give us is different, plainer and more troubling. The Gospels give us the bitter pill that Jesus had to die, because that’s the only possible conclusion to God taking flesh and coming among us.

The theologians give us theories about why Jesus had to die, but last night Luke left us with Jesus giving up the ghost and wondering if the cross is the best we can do, wondering if the only possible result of our encountering God is our choosing to push him out of the world on a cross.

The Gospels give us the painful irony:

Those who should’ve known best, those on whose expertise the world relies, those who presumed themselves to be God’s faithful people, those much like ourselves, they felt they had no other alternative but to forsake the God-who-is-human.

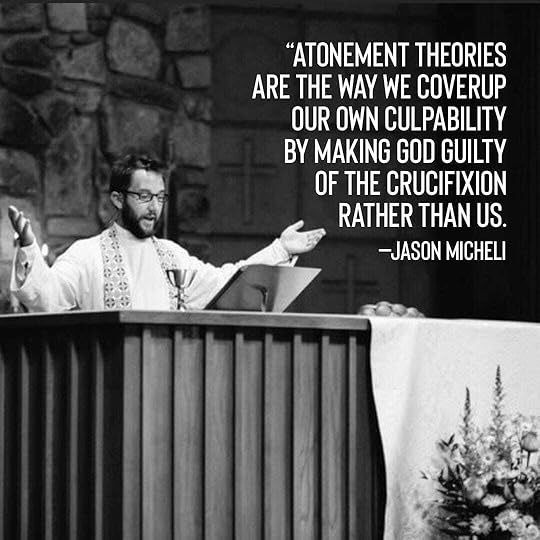

I think this is where all our theological explanations for the crucifixion fail:

They make the cross seem almost reasonable.

They make the cross a necessity for God to do away with sin.

Instead of a necessity for us to do away with God.

They make the cross seem inevitable, because of who God is, instead of confessing that the cross was inevitable, because of who we are.

That’s why the Palm Sunday crowd always tapers off as Holy Week winds its way to the End. We don’t want to confront the truth that, deep down, we prefer a God who watches from a safe, comfortable distance. When the Living God comes close, inevitably we defend ourselves. Christmas could come again and again and every time we would choose the cross.

We left in silence on Good Friday, because there’s not yet any good news.

There’s just the painful irony that all our hopes and aspirations and plans and talent and knowledge come to this: a confrontation with the God-who-is-human, a God who wills only to be gracious. It ends with Jesus dead.

The Gospels leave us to sit on Holy Saturday with the bitter irony that the only person who can touch us and heal us and forgive us and make us whole is dead, forsaken and shut up in a tomb.Our only prayer is that the Father won’t leave him there.Our only hope is the promise that all sad things will be made untrue. Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 7, 2023

The Mercy of God Can Never Now be a Theory Nor Even a Hope

Jesus is Laid in a Garden Tomb — John 19.40-42

On the last Tuesday of his life, Jesus once again entered Jerusalem and began to teach in the temple.

Once upon a time, Jesus says, a man planted a vineyard and leased the vineyard for tenants to care for it. When it came time for harvesting the grapes, the vineyard owner sent his servants to the vineyard to receive from the tenants a share of the fruit. But the tenants beat one servant, killed another servant, and stoned still another.

Yet the Owner of the Vineyard doesn’t react the way you might expect. He doesn’t call the cops or even cancel the contract he’s made them. No, the Owner elects to send his “beloved son.”

“They will listen to my son,” the Owner says.But no, they don’t listen to the Son.Or rather, they do listen to him and they don’t like what they hear.“Those tenants said to one another, “This is the heir. Come, let us kill him, and the inheritance will be ours,”” Jesus said in the temple on Tuesday.

Just two and half days later Jesus is proven him right.

The second Adam’s story ends with a garden for the very same reason the first Adam’s story ended in a garden.

The tenants in Jesus’s parable do not want to have any vineyard owner over them; likewise, we have no interest sharing in the Son’s relation to the Father because from Eve and Adam ever onward, we do not want there to be a Father.

We want to be the Owner.In Question 46 of his Summa, Thomas Aquinas wonders whether there was any other possible way of human deliverance besides the Passion of Christ? Aquinas considers the possible answers and admits that if we ponder the atonement in the abstract, then, yes, God certainly could have reconciled us otherwise than by Christ’s passion for nothing is impossible with God. Christ’s passion is not necessary for the Father to forgive us. Remember, Jesus shows up on the scene already announcing the pardon of God— that’s why his hearers kill him. Of course, considered abstractly, God could have reconciled us by means other than the passion. However, Aquinas reasons, the passion had to happen as it did precisely because the passion is not an abstraction.

Just as it is in Jesus’s parable— The crucifixion is an event in God’s own life.Too often we spend Good Fridays pondering the wrong mystery. We contemplate the deeper magic at work at Calvary. We wonder how what transpires in the passion works to reconcile us to God when, in fact, the beautiful mystery is that the events in Jerusalem and on Golgotha are events in the story of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Remember, Jesus is not merely human. Jesus is the God-who-is-human. Therefore, the events in Jerusalem and on Golgotha are events in the story of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. They become God’s history. They become God’s identity.

Why did Jesus have to die?Considered from God’s end, the crucifixion of the Son is what it cost the Father to be in fact— and not just conceptually— “the loving and merciful Father of the human persons that in fact exist.” It is well and good to posit that God is all-loving in the abstract.

In the suffering and death of the God-who-is-human and in the Father’s resurrection of him to those who betrayed and murdered him, we know concretely that God is merciful.As Jonathan Edwards grasped,

“Christ’s suffering is the anguish God undergoes to be actually mercifully within history; it is the pain of truly loving us. Thus, salvation is nothing more than that we abide with this Jesus and so with God the Son, abide so completely as to be truly one personal being with him in the triune life. Faith is our side of this closure; a love that is perfected as love unto death is Christ’s side of it, no lesser love being able to keep to us.”

In other words:

The cross is not what God inflicts upon Jesus in order to forgive us; the cross is what the God-who-is-human endures even as he forgives us.Salvation is nothing more and nothing less than sticking close to this God-who-is-human.

On Tuesday at the temple, Jesus finishes his parable with a question, “What do you reckon this father will do when he learns they’ve murdered his son in a shameful fashion and left his body forsaken like trash?

They answer so fast not a one even raised their hand.

“Surely, he will put those wretches to a miserable death!”

But no.

The mercy of God can never now be a theory nor even a hope.

Tonight and tomorrow and the next it is a fact established in history.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Because He Died, I Can Face Tomorrow

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

You can find the other Good Friday homilies HERE.

Blessed Three Days,

JM

Jesus Dies on the Cross — Mark 15.33-39

Several years ago, on Ash Wednesday, I suffered through my quarterly maintenance chemotherapy infusion. Leaving my oncologist’s office, I drove to the hospital to visit a parishioner named Jonathon.

He was a bit younger than me with a boy a bit younger than my youngest son. He got cancer a shortly before I did. He had thought he was in the clear, but on that Ash Wednesday he was dying. The palliative care doctor was speaking with him when I stepped through the clear, sliding ICU door. After the doctor left, our first bits of conversation were interrupted by a social worker, bringing with her dissonant grin a workbook, a fill-in-the-blank sort of book, that Jonathan could complete so that one day his boy will know who his dad was.

I sat next to the bed. I know from both from my training as a pastor and my experience as a patient, my job was neither to fix his feelings of forsakenness nor to protect God from them. My job was merely to hand over the promise that the Lord Jesus was for him.

I listened. I touched and embraced him. I met his eyes and accepted the tears in my own. Mostly, I sat and kept the silence as though we both were prostrate before the cross. I was present to him.

We were interrupted again when the hospital chaplain knocked softly and entered. He was dressed like an old school undertaker and was, he said without explanation or invitation, offering ashes. Because it was the easiest response, we both nodded our heads to receive the gritty, oily shadow of a cross. Earlier, my oncologist, as he’s wont to do, had drawn on the back of a box of latex gloves the standard deviation of the time I’ve likely got left. And now I sat with Jonathan whose own death was imminent.

We both leaned our foreheads into the chaplain’s bony thumb.

“Remember,” he whispered (as though we could forget), “to dust you came and to dust you shall return.”

As if every blip and beeping in the the ICU itself wasn’t already screaming the truth that breath will become air for all of us.

Jonathan shortly after I saw him.

Just like Jonathan, I am not getting out of life alive.

And neither are you.

Even the God-who-is-human dies.This is good news.The theologian Chris Green jokes about how not long ago, someone asked him what he thought Jesus was doing while he was dead. “I knew what the questioner expected me to say,” Chris writes, “of course I knew the answer he wanted to hear. But the right answer is that Jesus wasn’t doing anything while he was dead. That’s what it means to say he was dead!”

“…he suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried,” the creed puts the particulars plainly.

Make no mistake, Jesus’s story ends on Good Friday.He is dead.He is every bit as dead as you will be dead one day.His death was final, conclusive, definitive—as yours will be, and mine.This is good news.While it’s certainly true that the Gospels’s passion stories are so long because Christ’s passion was primarily a problem for which the Church had to take account, it’s nevertheless the case that dying and its antecedent despair, fear, and suffering are a part of living.

Our dying is a part of our living.

Dying is an unavoidable, universal part of living.

That Christ’s passion comprises no less than a sixth of the Gospel’s narrative means, perhaps fortuitously, that Jesus displays how to negotiate that part of our living that we call dying.This is good news.As Jesus’s moments become memories, he takes the time to forgive those who have trespassed against him, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” He does not pretend that everything’s alright, “My God, my God” he cries, “Why have you forsaken me?” In so doing, the dying Jesus frees those terrified at the prospect of his death by giving voice to his own anguish. Jesus shows forth how to live the part of our living that we call dying. He provides for his family’s care in his absence, “Behold,” he says to his beloved disciple, “Here is your mother.” “And from that hour,” John reports, “the disciple took Mary to his own home.” The night before—rather than waste time trying to stay alive at any cost, Jesus took care to hand over his unfinished work to his friends, “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet.”

Jesus exemplifies how to live the part of our living that we call dying.No, Jesus does more than exemplify the living we call dying.He transfigures it.In his letter to Cledonius, the ancient church father, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, formulates one of the most famous and critical maxims of the Christian faith,

“That which is not assumed is not healed.”

The full citation reads:

“That which is not assumed is not healed. That which is united to God, that will be saved. If half of Adam fell, also half will be taken up and healed. But if all of Adam fell, all of his nature will be united to God, and all of it will be saved.”

This is good news.

Gregory reminds us that the God-who-is-human has come to hallow the entirety of us, including our dying and death. There is no part of us, there is no part of our living, he does not assume in order to heal.

As the theologian Karl Rahner puts it,

“Jesus has accepted death. Therefore, this must be more than merely a descent into empty meaninglessness. He has accepted the state of being forsaken. Therefore, the overpowering sense of loneliness must still contain hidden within itself the promise of God’s blessed nearness. He has accepted total failure. Therefore, defeat can be a victory. He has accepted abandonment by God. Therefore, God is near even when we believe ourselves to have been abandoned by him. He has accepted all things. Therefore, all things are redeemed.”

One of my least favorite hymns sings, ““Because he lives, I can face tomorrow; because he lives, all fear is gone.” I dislike the hymn because it is closer to the true mystery of the incarnation to say that I can face tomorrow, with all its attendant fears, because he died.

That really, after all, is the other charge laid on me that day at Jonathan’s deathbed.

I was to assure him not simply that the Lord Jesus was for him.I was to remind him that the Lord Jesus was before him.He was safe in Christ’s death, to be sure, his sins forgiven.

But even more so, he was safe in death because Christ had entered death.

And even there, Christ had hallowed out a place where he may be found.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

There is No Deeper Magic at Work

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Jesus is Nailed to the Cross — Mark 15.24-25

When I was a student in seminary Princeton, I took a course on the Gospel of Mark. Our professor, Dr. Donald Juel made sure that by the end of the semester Markʼs was our favorite of the four Gospels. It even became my favorite book of the Bible.

Dr. Juel began the first class of the course with a simple question,

“What would you say about a book that spent one-sixth of its story narrating the death of the main character?”

A classmate of mine responded, “Iʼd say that it sounded like the author was a person who had not come to terms with the death of someone they loved.”

Dr. Juel followed with another question, “Isnʼt it ironic that even though Jesus was only dead for two days, not even two full days, his followers had such incredible difficulty coming to terms with that death? Jesus didn’t stay dead, but his followers never could quite settle that death.Why is that, do you think?”

Our class spent a long time with that question.

And so has the Church, if only implicitly.

Take the Church’s dogma, for instance. The Nicene Creed or the creed attributed to the Apostles both hammer away at the fact of Jesus’s death, going so far as to name the God-who-is-Human’s executioner in our profession of faith, “…crucified under Pontius Pilate.”

Yet the creeds do not venture to assert the meaning of his death.The creeds make a matter of orthodoxy such doctrines as the incarnation, the virgin birth, and Christ’s bodily resurrection, but they say not a word about how exactly the Father saves us through the Son in their Spirit. For example, there are no assertions in the creeds such as, “Jesus died in our stead” or “The Son satisfied a debt to the Father we could not pay.”

On the basis of the creeds, you can deny any explanation of the atonement or all of them together. You can deny even the possibility of an explanation and remain a perfectly orthodox believer.

We boast in the cross, Martin Luther writes, because in nailing him to the cross, God has nailed all our sins there once and for all. They’re forgotten in his body. Luther may be right. Indeed it’s a matter of simple theo-logic. If the wages of sin is death, then Jesus, who is without sin of his own, must be bearing another’s sin in him. Otherwise, try as we might, it would be impossible for Jesus to die.

Luther may be right that, as Pilate’s goons nail Jesus to the tree, the Father simultaneously nails all our sins into blessed oblivion. However, a straightforward reading of the passion story will not allow us to draw such a conclusion.

Mark, for example, makes no such interpretative move.

Mark imputes no meaning to the death of Jesus.Mark is even reticent to provide any details about the manner of his death. One of the tradition’s Stations of the Cross is entitled “Jesus is Nailed to the Cross,” yet the Gospels themselves omit the grisly detail. “And they crucified him,” is all the evangelists dare to report.

The Gospel writers do not project any theories onto the narrative of Jesus’s death. The Gospel writers do not peek behind the narrative of Jesus’s death to find a deeper concept or a universal principle at work. The Gospel writers do not show a deeper magic at work in the Son’s suffering.

What the Gospel writers do is bind the story of Jesus’s death and the story of Jesus’s of resurrection together into one single narrative.Thus, it’s not merely that you must go through Good Friday in order to get to Easter Sunday; it’s that the crucifixion has no meaning at all apart from the resurrection. The Gospel writers description of Jesus’s death is already drawn by the light of the resurrection. Peter preaches just so in the Book of Acts, “You all killed him, but God raised him up.”

That is, the crucifixion is God’s salvific action because God overcomes it by the resurrection.Mark spends one-sixth of his Gospel narrating the suffering and death of Jesus because the suffering and death of Jesus were not understood to be saving. They were recognized as a problem to resolved. After all, God’s own law stipulates clearly, “Anyone who is hanged on a tree is under God’s curse.” Therefore, the Gospel writers not only bind the cross to the empty tomb, they also integrate both into the sweeping narrative of Israel’s scriptures. Given that God’s promise to exilic Israel had in fact happened to the one man— God had raised him from the dead— given that God had fulfilled his promise, then it followed, even if shockingly so, that this one man’s crucifixion must have been in continuity with the plot of Israel’s entire history.

Accordingly, the first Christians heard Jesus’s thirst upon the cross as the Psalmist’s thirst. Israel’s cry of dereliction in Psalm 22 becomes his own plea, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Even the way in which the passion story ends recalls Zechariah’s terrible prophecy,

“Awake, O sword, against my shepherd…that the sheep may be scattered. I will turn my hand against the little ones…When they look on the one whom they have pierced, they shall mourn for him.”

If we want to know how the Son’s death can have reconciled straying sheep to the Father, the Gospels provide us no theoretically developed answer. That it does so the Gospels simply assume in light of the Old Testament scriptures. And so there can be no explanation to Jesus’s death. There can only be a stubborn return to the story. “Therefore what is required as the crucifixion’s right interpretation,” Robert Jenson writes, “is for us to tell this story to one another and to God as a story about him and about ourselves. The passion must live in the church as the church’s account of herself and her God before God and the world.”

Hence, we ought to pray that we will never be any different than Mark and the first disciples.

If we ever did finally come to terms with Jesus’s death, we will have strayed like sheep, failed rather than triumphed.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

The Crucifixion Puts Jesus’s Life and Teaching to the Test

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Jesus Speaks to the Women — Luke 23.27-31

Not all who witnessed Jesus’s trial and torture jeered at him or colluded with the authorities or turned a blind eye to the whole sordid affair. According to Luke, as Jesus trod his beleaguered path to Calvary, a multitude of women trailed behind him, mourning and lamenting for him.

Their public sorrow in his train is the closest anyone in the passion story comes to protesting, “Do not crucify him!” Yet hearing them weep, the Lord Jesus does not express gratitude for their solidarity.He turns to them and tells them they should instead weep for themselves and their children. Echoing the prophet Hosea, Jesus says, “If they do these things when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?” In the context of impending crucifixion, it means, “If Jesus is not spared the cruelty of the cross, how can God’s unfaithful people possibly hope to escape divine judgment?” Jesus’s sermon to the Daughters of Jerusalem is the seventh time in Luke’s Gospel that he has prophesied looming doom for Jerusalem and her temple.

Put differently, Jesus teaches and preaches his message to the last.Just so, this is another predicate the Gospel narratives will allow us to draw from the death of Jesus:

The crucifixion puts Jesus’s life and teaching to the test.

Such a premise requires that we remember what is so widely forgotten among believers.

Namely:

The cross was important to the first Christians precisely because the cross was a problem for them.Therein is the irony of the Passion.

Much of the tradition’s best and most beautiful art centers on Good Friday, yet— perhaps surprisingly— the crucifixion does not so center in the understanding of the primal Church. The Gospel message is not “Christ and him crucified.” The Gospel message, as Peter makes clear in the first Christian sermon, is Jesus, whom we crucified, has been raised from the dead. The good news is the resurrection of the crucified Jesus. Indeed a fatal flaw in nearly all so-called atonement theories is that they have no need for this central claim of the first Christians, “God raised Jesus from the dead.” Rather than understanding the crucifixion as saving in and of itself, it’s more biblically accurate to say that the crucifixion was not an original element of the faith. For instance, the reason the passion story makes up the bulk of all four Gospel narratives is that the crucifixion was a problem to be accounted for not a punishment to be indulged or delighted in.

Again, in Peter’s first Christian preaching:

The cross is not what God undergoes in order to reconcile us; the cross is what God overcomes in reconciling us.

Granting the fact that the crucifixion is not an original element of the Church’s proclamation, we can nonetheless make an essential claim about the cross: Jesus’s death puts his life to the test. The high priest himself speaks the truth of what is at stake in Jesus’s suffering and death, “Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed One?” Jesus answers only with an enigmatic, “I AM.” Thereupon the the priests enlist the pagan Pilate to condemn him to crucifixion. In so doing, they pose their question to the Blessed One himself, “Is he the Messiah, the Son of God?” Jesus teaches to the last.

And in the end, his death puts his teaching to the test: Would the Father acknowledge this Jesus as his Son?Those who ridicule Jesus on Golgotha are not wrong in their reasoning. If he is in fact the Blessed One’s Son, then the Father should rescue him from his plight, deliver him from this ghastly death. But the Father lets the question linger to extremity, handing over the Son, who surrenders their Spirit, to death.

“Is he the Messiah, the Son of God?”

“Yes,” the Father answers with an empty grave.

The Father answers the question that the Son’s death puts to his life.

And to his teaching.

Yes, Jesus is the Messiah.

Yes, Jesus is in the Trinity.

Yes, the Kingdom is at hand wherever he is present.

Yes, the Son is your salvation.

Yes, the poor are blessed.

Yes, the peacemakers are called children of God.

Yes, the merciful will be shown mercy.

Yes, those who hunger and thirst for justice will be filled.

And yes, woe to you who are rich and full and well-regarded.

As Robert Jenson writes,

“The crucifixion put [the question] up to the Father: Would he stand to this alleged Son? To this candidate to be his own self-identifying Word? Would he be a God who, for example, hosts publicans and sinner, who justifies the ungodly? The resurrection was the Father’s Yes. We may say: the resurrection settled that the crucifixion’s sort of God is indeed the one God…Or, the crucifixion settled who and what God is; the resurrection settled that this God is. And just so the crucifixion settled also who and what we are.”

The Father answers the high priest’s question with an empty grave.

Therefore, we know what the weeping Daughters of Jerusalem cannot know.

What Caiphas cannot know.

The bloodied one before them who speaks (rightly) of divine judgment is the Judge about to be judged in their stead.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

He Did Not Shout "Do NOT Crucify Him!"

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Simon of Cyrene Helps Carry Christ’s Cross — Mark 15.21

Simon is how most people participate in injustice.

We’re just bystanders and passersby until, like a wave crashing over us, evil’s undertow pulls us into it.

Simon must be on pilgrimage to Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover. Cyrene is a colony in Libya. Simon has come a long way only to find himself pulled from the crowd and compelled to carry the instrument of torture and death by which the best and brightest of Church and State, along with their enabling mob, will murder God. It’s tempting to imagine Simon’s act captured on video and streamed onto social media. If Good Friday took place in the twenty-first century instead of the first, how many observers would cancel Simon of Cyrene, dox him, or charge him as complicit in the miscarriage of justice?

Mark characterizes Simon as a passerby, which could mean either he is an onlooker in the crowd, intrigued or intimidated by the ghastly spectacle or it could mean he’s like those in Jesus’s parable who passed by the man in the ditch, too busy to be bothered by the brutality in the street.

Did Simon join the crowd when they shouted, “Crucify him!”We do not know.We do know Simon did not shout, “Do not crucify him!”No one so shouted, “Do not crucify him!”Likewise, not everyone betrayed Jesus for pieces of silver but no one attempted to buy his release.

Mark does not report that Christ needed someone to carry his cross:

“They began saluting him, ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’ They struck his head with a reed, spat upon him, and knelt down in homage to him. After mocking him, they stripped him of the purple cloak and put his own clothes on him. Then they led him out to crucify him. They compelled a passer-by, who was coming in from the country, to carry his cross; it was Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus.”

Mark does not say that the Lord Jesus needed Simon to carry his cross.

Earlier in the week, on Palm Sunday, Jesus did not need the disciples to lift him and place him on the donkey— it was only a foal; he could swing his leg over it. Nevertheless, Jesus humbly submitted to them and allowed them to lift him onto the ass. At the beginning of his ministry, Jesus did not need to be baptized with John’s baptism. He had no sins to repent. Nevertheless, Jesus humbly submitted to John and allowed him to wash away his sins. There is no indication in Mark’s Gospel that the Lord Jesus needs Simon’s help; nevertheless, Jesus humbly submits and makes a place for this passerby in his passion. As Cyril of Alexandria says, the wonder is that Jesus, the Beloved, not only shares with us what is his, but also includes us in who he is.

In this detail, Simon helping Jesus, the Gospel wants you to see not the uniqueness or honor of Simon but the constancy and steadfastness of Jesus.

Even now, Jesus is who Jesus has always been. He humbly submits and accommodates Simon though he needs him not. The Gospel wants you to see not the distinctiveness of Simon’s character—we don’t know anything about him. The Gospel wants you to see instead the consistency of Christ’s identity, the Man for Others, always.

As many in my parish know, Gary Sherfey’s last words to his wife were, “I love you.” For that matter, Gary’s last words to me also were, “I love you.” To those who know Gary, such a benediction sums up his life perfectly. Conversely, if Gary had left this life striking a discordant note (“I hate you. Get out of here. Shut the hell up!”) it would have unsettled the entire story by which we know and name Gary.

Before we glean any other meaning from Good Friday, we can and must say this much: Christ’s death forever settles his identity.What the tradition labels “atonement theories,” explanations for how Christ reconciles us to God, nearly all suffer the same fatal defect; namely, they do not start straightforwardly from the Gospel narratives. The Gospel of Mark, for example, permits us to draw no other conclusion from the crucifixion other than the fact that Jesus’s death brings an end to Jesus’s life. Therefore, Mark’s Gospel allows us to assert at least this premise: Christ’s death permanently settles his identity.

Until the story comes to an end, it is not settled whose story will have been written. What if George Washington had betrayed his country in his old age? What if Abraham Lincoln had gone home after the play only to bungle Reconstruction? What if Jesus had said no to Pilate’s question, “Are you the King of the Jews?” What if Christ had heeded the crowd and come down off his cross?

That the Man for Others died rather than seek his own kingdom settles that he is the Man for Others, always.The Lord Jesus can never now be other than who he was.Correlatively, this means you can never now be otherwise. You are right now and you always will be one the Man for Others is for.

Straightforwardly, Christ’s death brings an end to Christ’s life.

In so doing, Jesus’s death settles Jesus’s identity.

From this simple premise, Martin Luther constructed an equally simple theory of the atonement.

Jesus died, Luther argues in the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, in order to transform all his promises into a testament.

Of course the distinguishing feature of a last will and testament is that it becomes binding and irrevocable exactly because the promise-maker has died. By settling his identity once and for all, Jesus’s death removes Jesus’s promises from any possibility of retraction or qualification. His unconditional promises cannot be undone. Because he died, the Risen Jesus has no choice but to execute the promises of Mary’s son.

This is the basis and authority on which I can declare unto you the entire forgiveness of your sins because the identity of the Lord is a settled matter. This is the basis on which we must pray tonight for the likes of Caiphas and Judas and Pontius Pilate and Simon of Cyrene (assuming his motives were as mixed as ours always are).

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

To Unmask Satan’s Temptations Christ Must be Tempted By Them

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Jesus Accepts His Cross — John 19.6, 15-17

From a wealthy New England family, William Congdon volunteered as an ambulance driver during World War II. He was the first American to enter the death camp at Bergen Belsen, images from which left an indelible impression on him. Inspired by the artwork he saw during his service in Europe, Congdon took up painting after the war and became one of the century’s most notable exemplars of abstract expressionism. In 1959, after a visit to Assisi, Congdon converted to Christianity and thereafter painted bleak iterations of the crucifixion as though both the cross and the concentration camp haunted him. His most famous painting, 1960’s Crucifixion No. 2, renders Jesus as the only object to view. In it, there are no soldiers mocking Jesus nor any thieves deriding him or asking his mercy. There is no purple robe or chief priests. There is no crown of thorns or weeping mother. There is no crowd jeering him to come down from his cross; for that matter, there is no cross. His body itself is the cross, stretched out in the shape of T on a sheer black backdrop. As though nailed to nothingness, he is the solitary spectacle we are meant to behold.

Congdon’s artwork is certainly arresting and surely truthful in its bleak refusal of any beauty to be found behind Christ’s passion; however, the Gospel narratives themselves do not put Christ on display as much as everyone else who contribute to handing Christ his cross to carry to Calvary.

Pontius Pilate sends a man, whom he knows to be innocent, to a brutal and dehumanizing death. “Crucify him yourselves,” Pilate tells the chief priests, "I find no guilt in him.” Nevertheless, without a second thought, Pilate condemns Jesus to a manner of execution so ghastly the word crux was verboten on the lips of polite Roman citizens.

Pilate not Jesus is the one the scriptures put on display.Not only is Jesus not guilty, he alone is the righteous one.

But those who know of righteousness, the chief priests, they plead for his crucifixion. Under the law, the priests already possess the authority to put him to death. In fact, they’ve attempted to stone Jesus twice. It’s not that they lack the authority to put Jesus to death. It’s that they want Jesus to die a death only Rome can execute. It’s no longer enough for them to stone Jesus. They want Jesus to be crucified. According to the Book of Deuteronomy, “anyone hung on a tree is under God’s curse.” Thus, they want Jesus crucified because crucifixion will invalidate Jesus. They want more than the death of Christ. They want to nail Jesus’s Kingdom message into blessed oblivion.

They are the spectacle the scriptures want you to see.

When Pilate sarcastically arraigns the would-be king of this kingdom before the chief priests (“Behold, your King!”), the chief priests, those chosen from the tribe of Levi to intercede on behalf of the covenant people so that Israel would be a light to the nations, having no other god but Yahweh, exclaim, “We have no other king but Caesar.”

If Israel’s original failure in the Old Testament is the desire to have a king like the other nations, then Israel’s original sin happens here, not in the Garden but on Good Friday, when they choose the king named Caesar over the true God.

Jesus is not the one on display.

Perhaps this is why he is so poised before Pilate. In verse eleven, Jesus minimizes Pilate’s authority by suggesting the Father’s authority alone has brought Jesus before this judge.

Just as the Holy Spirit thrust Jesus before the tempter in the desert immediately following his baptism, the Father has handed him over to Pilate and the priests and brought him to the place the Gospel of John calls Gabbatha, the judgment seat.

For what purpose?

The Epistle to the Colossians claims that Christ in his passion unmasks the rulers and authorities and puts them on display in open shame.

Another question:

What is underneath the masks Jesus removes from those rulers?

A better question:

Who is the person behind their guises which Jesus unveils?

Precisely because the devil is a person without a self, an agency without substance, a being without a body— invisible, we require help to identify him.

In other words, to unmask Satan’s temptations Christ must be tempted by them.

The Father brings Jesus before Pilate and the priests to draw Satan out; so that, we might see the way in which the Tempter lures us away from the true God.

In this case, the chief lure is the satanic marriage between Religion Inc. (“We have no king but Caesar”) and Empire (“I find no guilt in him”).The Father brings the Son before Pilate and the priests, puts them on the display, so we might see how the Enemy attempts to deceive us still. The tradition’s language of Christ’s saving work being a struggle with an Opponent, for all its apparent mythological character, is literal reporting. Indeed you need not read contemporary reporting to know that religious pretense and political power remain the primary way the Prince of Lies deceives and misleads God’s people.

In his famous hymn, Martin Luther professes that “one little word shall him,” the devil. Beaten and bloodied, altogether unremarkable, about to accept a cross, Jesus is the little word who fells him. And he does here. He does so exactly by unmasking him. Robert Jenson elaborates by writing,

“Once the devil is identified, he is too laughable to be taken seriously, but we have to know in which direction to throw the inkwell.”

In other words, Jesus is not like William Congdon’s Crucifixion No. 2. He is not a solitary spectacle stretched across the sheer black nothingness of our world. He is instead like a vial of black ink splashed against a white page so that we might see the unseen Enemy who stalks us still.

Thus, as the Lord Jesus accepts his cross, he is not the one who is on display.

It is his Adversary.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers