That All Sad Things will be Made Untrue

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“And having said this,” Luke concluded for us last night, “Jesus breathed his last.” Or, as the King James Version puts it,“Having said thus, Jesus gave up the ghost.”

Just as it sounds odd to hear that in her belly Mary bore the Maker of Heaven and Earth, the inconceivability should linger with us over Holy Saturday.

The God-who-is-human had an able executioner.He is dead.“What was Jesus doing when he was dead?” some will wonder, too shy to take the simple truth of today with an open hand.

Answer: Nothing.

Jesus wasn’t doing anything while he was dead. He was dead. His story ended at Golgotha on Good Friday, the dead leader of a movement with no followers. On Saturday, the God-who-is-human is every bit as dead as you will be dead one day. His death was final, conclusive, definitive—as yours will be, and mine.

John tells us at the beginning of his Gospel that no one can see the Father apart from the Son, which means when Jesus is dead, the second person of the Trinity is as good as gone.

Jesus told us that he alone is the way, the truth, and the life— that no one can come to the Father except by the Son— but his way led him to a cross. His way had been done away by the way of the world.

God is dead.

Elected over Barabbas, Jesus became the persecuted for righteousness’s sake. Giving up his spirit, Jesus became the poor in spirit. Dying on a cross, Jesus became the beatitudes.

The beatitudes are Jesus, the God-who-is-human.And we are the antitheses.In all our theologizing about the story, we conveniently forget— Judaism was a shining light in the ancient world, offering not only a visible testimony to God who made the heavens and the earth, but a way of life that promised order and stability and well-being of the neighbor. And in a world threatened by anarchy and barbarism, the Roman empire brought peace and unity to a frightening and chaotic world. The people who got Jesus to give up the ghost— Pilate and his soldiers, the chief priests and the Passover pilgrims gathered in Jerusalem— they were all from the best of society, not the worst. And they were all doing what they were appointed to do. What they thought they had to do. What they thought was necessary for the public good.

Even the chief priests’s reasoning, if we admit it, is right: “It’s better for one man to die than for all to die...”

That’s a perfectly rational position.

It’s the position around which we’ve ordered the way of the world.

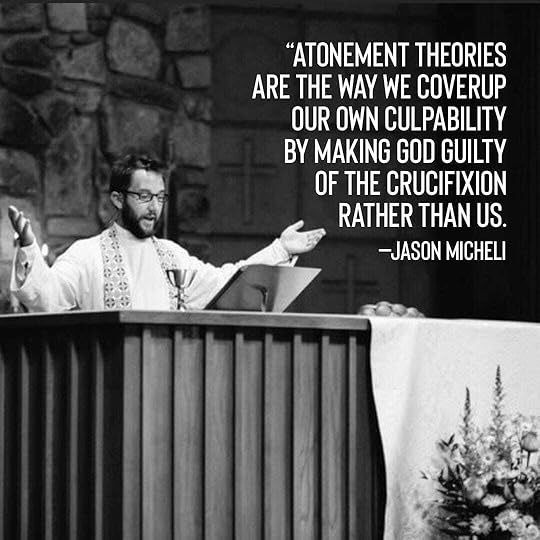

The theologians give explanations: that Jesus had to die in order for God to be gracious, that Jesus had to die in order for God to forgive us of our sin, that Jesus had to die to pay a debt we owed, but could not pay ourselves. But, in the end, what the Gospels give us is different, plainer and more troubling. The Gospels give us the bitter pill that Jesus had to die, because that’s the only possible conclusion to God taking flesh and coming among us.

The theologians give us theories about why Jesus had to die, but last night Luke left us with Jesus giving up the ghost and wondering if the cross is the best we can do, wondering if the only possible result of our encountering God is our choosing to push him out of the world on a cross.

The Gospels give us the painful irony:

Those who should’ve known best, those on whose expertise the world relies, those who presumed themselves to be God’s faithful people, those much like ourselves, they felt they had no other alternative but to forsake the God-who-is-human.

I think this is where all our theological explanations for the crucifixion fail:

They make the cross seem almost reasonable.

They make the cross a necessity for God to do away with sin.

Instead of a necessity for us to do away with God.

They make the cross seem inevitable, because of who God is, instead of confessing that the cross was inevitable, because of who we are.

That’s why the Palm Sunday crowd always tapers off as Holy Week winds its way to the End. We don’t want to confront the truth that, deep down, we prefer a God who watches from a safe, comfortable distance. When the Living God comes close, inevitably we defend ourselves. Christmas could come again and again and every time we would choose the cross.

We left in silence on Good Friday, because there’s not yet any good news.

There’s just the painful irony that all our hopes and aspirations and plans and talent and knowledge come to this: a confrontation with the God-who-is-human, a God who wills only to be gracious. It ends with Jesus dead.

The Gospels leave us to sit on Holy Saturday with the bitter irony that the only person who can touch us and heal us and forgive us and make us whole is dead, forsaken and shut up in a tomb.Our only prayer is that the Father won’t leave him there.Our only hope is the promise that all sad things will be made untrue. Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers