Jason Micheli's Blog, page 76

May 12, 2023

The Areopagus is Not Everywhere

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Acts 17.22-31

Though I’m known to creep regularly upon the half-hour threshold, the proclamation of the gospel, in point of fact, requires only three words, a subject and a predicate: Jesus is risen. If preaching fails to open up its hearers’s future as a promise rather than a threat— Jesus, the friend of sinners— is risen, then the preaching has not been gospel preaching. As Father Al Kimel writes: “The gospel is proclamation of the risen Lord cloaked in eschatological promise.”

Jesus lives with death behind him!

This is the novum the apostles raced out into the Mediterranean world to transmit. This spare and simple message, however, is more complex than the sum of its words. The Risen Jesus is not merely the content of the proclamation; the Father’s Son is the speaker.

Sermons and sacraments are Christ’s self-communication.The Lord Jesus addresses us from the future into which the Father resurrected him; he does so address us through word and water, loaf and cup.

Critical to Karl Barth’s emergency homiletic, the Second Helvetic Confession puts it so: “The preaching of the Word of God is the Word of God.”

You really spoke to me today when you said… the parishioner will say to me often before adumbrating observations and proclamations that were not— at least not as I thought— in the sermon I’d prepared. This is because, as a preacher, I am as ordinary and passive a weapon as bread and wine. The Risen Jesus is the active agent of the gospel message, “Jesus is risen!” Jesus is the preacher, the proclamation, and the present, for the gospel is a word in which Christ gifts himself to us.

Because the Jesus-who-is-not-dead speaks from the last future through the day’s preacher to address listeners in precise present moments, the gospel, Robert Jenson insists, can never be spoken the same way twice.May 11, 2023

Theological Fragments

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Earlier this week, I enjoyed the privilege of moderating a panel discussion at St. Louis University of Dr. Ruben Rosario Rodriguez’s new book, Theological Fragments: Confessing What We Know and Cannot Know about an Infinite God.

My interlocutors were:

Nichole Flores, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia and author of The Aesthetics of Solidarity: Our Lady of Guadalupe and American Democracy.

Scott Paeth, Professor of Religious Studies and Peace, Justice, and Conflict Studies at DePaul University and coeditor of Shaping Public Theology: Selections from the Writings of Max L. Stackhouse

Aristotle Papanikolaou, Archbishop Demetrios Chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture at Fordham University and author of The Mystical as Political

I enjoyed the conversation and the opportunity to meet new friends. As you’ll hear at the top, Ruben is a wonderful teacher. Do him a solid, then, and order the book!

FYI— The panel begins at the 40:00 mark in the video.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 10, 2023

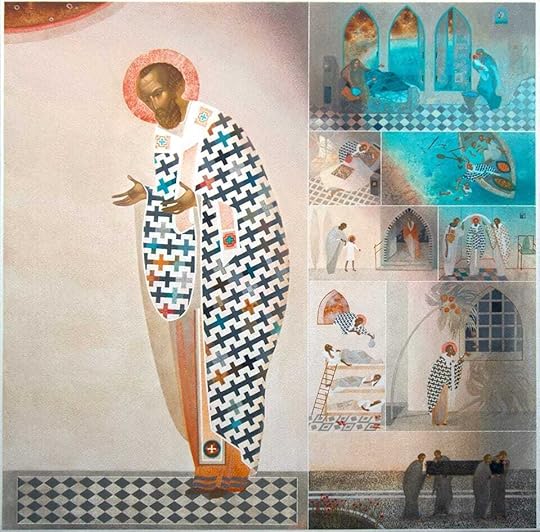

Q: How Should We Picture God?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, including this catechism, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

12. How are we to picture God?We should not think of God as the pagans of either past or present times do.

Therefore, we need avoid their two errors.

May 9, 2023

Believers in Jesus should be the last people to board Flight 93’s

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

1 Peter 3:13-22

There is so much bad news, yet— it’s like driving slow past a car wreck— I can’t not stare. Day after day, night after night, I can’t unplug. I can’t put away my phone. I can’t stop checking the headlines. I can’t turn off the notifications.

Psychologists call it the “Mean World Syndrome.”Namely, the more media you consume that depicts the world as a violent, dangerous place the more you will view the world as a violent, dangerous place which, in turn, actually makes the world a more violent, dangerous place. If you’re convinced the world is a dangerous place you’re more likely to resort to— or justify— violence. Worse, because what’s wrong with the world is other people, doom-scrolling releases in our brains the same endorphin rush we get by participating in our self-righteous, like-minded tribes. We look for the bad news, and then we judge and we point fingers and we demonize and we cancel because it makes us feel good.

Chemically— bad news makes us feel good.A research scientist at Harvard’s School of Public Health says that “as humans we have a natural tendency to pay more attention to negative news.”

It’s natural.

Meaning, for evolutionary reasons, we’re hard-wired to pay more attention to bad news than to good news.We find danger before we find comfort. We notice brokenness before we see beauty. We see the not yet at the expense of the already. We do this as Christians too. We doom-scroll with the eyes of faith. We fix our attention on the fallenness of the world and the far away-ness of the Kingdom. We obsess over our sins and, in doing so, we conjure a god who is angry at us. We focus on our neighbor’s sins, by what they’ve done or left undone, and, in doing so, we conjure a license to be angry at them.

It’s easy to notice what’s wrong with the world.That’s no achievement.The slow and steady process of natural selection has made sure your default gaze is trained on the bad news, which is a scientific, doctor-approved reason why, in the Church, we can never assume the Gospel.

Where the Gospel is assumed, the Gospel is endangered. Where the Gospel is assumed, the Gospel is endangered because survival of the fittest has fashioned us to pay attention to bad news rather than good news. Therefore, before I go any further, allow me to give you the goods of the Gospel:

Almighty God, the Everlasting Father, has elected you in Jesus Christ from before the foundation of the world. His covenant in Jesus Christ, to be your God and for you to be his people, precedes creation itself. Before there was anything or anyone, God had determined in Christ Jesus not to be God without you.

Because this one man died to Sin, all have died. Your life is hidden now in Christ with God. Nothing you do or leave undone can evict you from him who is your home. And because you are in Christ, no matter what your eyes tell you— take it on faith— you are a new creation (even you). You have been begotten anew by the Word of God, Jesus Christ.

And if you wander in your life, if you wobble in your faith, if you wonder if your sin is stronger than his grace, then look to your baptism. As the apostle Peter says in Sunday’s lectionary epistle reading, your baptism is tangible, visible, datable- in-time reminder that Christ has saved you. Christ suffered for sins once for everybody, Peter proclaims. Christ the only Righteous One suffered for the remainder of us, the all-inclusive category called the unrighteous. And Christ suffered, Peter says, NOT in order to beckon us to God but in order to bring us all by his lonesome to God.

You’re already home free, gratis.

God’s grace in Jesus Christ isn’t cheap. It’s not even expensive. It’s free.

And not only free— it’s finished and final.

Not only is this the good news, it’s good news.

No matter what the headlines say, no matter what your eyes see, no matter what that voice inside your head whispers, in Jesus Christ everything that is wrong in the world— including everything wrong in you— has already been and is now being and will yet be rectified.

Made right, the Gospel promises.

You can’t hear news like that anywhere else BUT the Church.Before COVID-19, you had to get up at an inconvenient hour, get dressed up, and get yourself to church to hear news so strange and good. News that is neither sentimental nor cynical.

News that’s a counter-narrative.

A resistance.

An act of resistance to the world that we’ve made in our image.

As the Church, we can never assume the good news, roll up our sleeves, and get about fixing the brokenness of the world. We can never assume the good news, not simply because we’re hardwired to fixate on the bad news.

We can never assume the Gospel because, notice how the apostle Peter frames it in our text, the good news of the finished work of Jesus Christ— it is the basis from which we engage the brokenness of the world.

In Sunday’s lectionary epistle, the apostle Peter is in the middle of exhorting the messianic community to do good in the world. To do good in the world and, if necessary, to “suffer for righteousness’ sake.” That is, for the sake of justice.

But notice, for Peter, what compels us to do good and suffer for the sake of justice in the world:

“For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit, in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison… and through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who sits at the right hand of God, with every authority and all the Powers now made subject to him.”

Peter does not exhort the Church to do justice in the world because of all the injustice in the world. Peter does not urge believers to do good because of all that is wrong in the world. Peter does not push the messianic community to bear witness to the cruciform way of Jesus Christ because so much reconciling work yet remains to be done.

No.Peter orders us out into the world to bear witness to the cruciform way of Christ because everything has already been done.It’s not the brokenness of the world that enlists us to engage the world with the way of Jesus.It’s the beauty of what Christ has already accomplished for the world that sends us out into the world.May 8, 2023

What's Theology Got to Do with It?

Here is the second discussion from our Monday night online sessions with Tony Robinson on his book, What's Theology Got to Do with It? Convictions, Vitality, and the Church.

You can sign up HERE for future session.

A little more information on the book and Tony:

or congregations seeking renewed purpose and vitality this book gets to the heart of the matter. One of the leading voices on congregational life and leadership, Anthony Robinson makes the case that congregations should openly express their beliefs and values to clarify their purpose. Doing so opens up new avenues for transforming worship, promoting spiritual formation, and forwarding a church's mission. The wisdom invested in this book is powerful enough to shape a ministry and lead a congregation to its call.

Tony is a writer and preacher, teacher and semi-practical theologian. The author of 14 books, including “Transforming Congregational Culture,” “Changing the Conversation,” and “The Book of Acts for a New Day.” After serving four congregations over a thirty year period, he taught in several seminaries in the U.S. and Canada, consulted with congregations and their leaders and wrote a bunch. These days he divides his time between Seattle and his beloved Wallowa Mountains in Oregon.

Grace Creates Impossible Possibilities

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

1 Peter 3:13-22

When our oldest son was in Kindergarten, my wife and I received an email from his teacher requesting a meeting. In her classroom early one morning before school, sitting across from her on tiny plastic chairs, she explained to us her concern that our otherwise cheerful and compliant child stubbornly refused to put his hand over his heart and recite the pledge of allegiance with his classmates.

“Well, what’s he do?” I asked her.

“He stands next to his desk politely and respectfully,” she said, “but— I’ve insisted several times— he refuses to participate in the pledge.”

“Good,” I said.

“Um, excuse me? Good?””

“That’s what we’ve taught him to do,” my wife explained, “to be polite and respectful, but not to participate in the pledge.”

She looked at us like we were strange.

“We, of course, teach our kids to love their country and to understand what makes it exceptional,” my wife added. “But not to pledge his allegiance.”

“I don’t understand,” his teacher said and, it was clear, she really didn’t understand.

“We’re Christians,” I said, “Jesus is Lord. We’ve taught them that their allegiance is to God alone and that baptism is the only pledge they are to swear to.”

“Uh, okay,” she said, “I just thought you’d want to know.

“Oh no, thanks for telling us,” I said, “We’re so proud of him.”

As we pushed back the little plastic chairs and got up to leave, she looked at us like we were the oddest people she’d ever encountered.

Now, I certainly I don’t share that story to make myself appear heroically holy. I divulge it because, to my embarrassment, that’s one of the only few occasions when someone has regarded me as peculiar enough to inquire about the hope that is within me.

Given what God has gone and done, gratis, without asking for your input or opinion. Given what God has done in Jesus Christ, putting an end to sinful humanity in Christ’s death and establishing the new future of humanity in Christ’s resurrection. Given that, because Christ died for all, all have died. Given that your life is hidden now in Christ where you are a new creation upon whom Sin and Death have no claim…

Given the Good News that is the Gospel, you have a decision to make:To be or not to be?Will you live in a manner that corresponds to who you are, really are?Or, will you contradict your true identity by refusing to live in a manner that makes no sense if Jesus Christ is not Lord?“To be or not to be,” that is the question in light of what God has gone and done. Will you become who you already are? Or, will you settle for a life that’s something less meaningful, something unreal even?

The disorienting implications that follow from the Good News is that the perfect and finished work of Jesus Christ, the present-tense Lordship of Jesus Christ, provides the basis for a free and revolutionary life.

This is why the Apostle Peter, in the lectionary epistle for the Sixth Sunday of Eastertide, assumes that those who know they are in Christ are living in a manner sufficiently peculiar, so as to provoke questions from those who are not Christian:

“Always be ready to give an account of the hope that is within you.”

Go back and read verses eight through twelve.

The Apostle Peter’s not talking about our beliefs. The Apostle Peter’s talking about the behavior of the messianic community.In other words, the messianic community proclaims the Gospel when they live the cruciform way of the Messiah.

We preach the Gospel by living in a manner that makes no sense if God has not raised Jesus from the dead.The Lordship of Jesus Christ may be objective reality, but it is not obvious.Therefore, such a strange way of life should provoke questions.How can you turn the other cheek? How can you walk another mile? How can you give your shirt as well as your coat? How can you forsake your property and possessions? How can you not desire to wield power the way the world does? How can you forgive her for leaving your son dead on the side of the road?

And when your counter-intuitive, cruciform way of life provokes questions, be prepared to give an apologia of the hope that is within you.

Notice—

There are two expectations implicit in the Apostle Peter’s exhortation.

The first expectation is that you are living in a manner odd enough to elicit questions from unbelievers.

The second expectation is that you are equipped to articulate to unbelievers the conviction that can account for such a way of life.

As far as the first expectation goes, perhaps it’s best if we just repent and confess.

Most of us live our lives as functional atheists.May 7, 2023

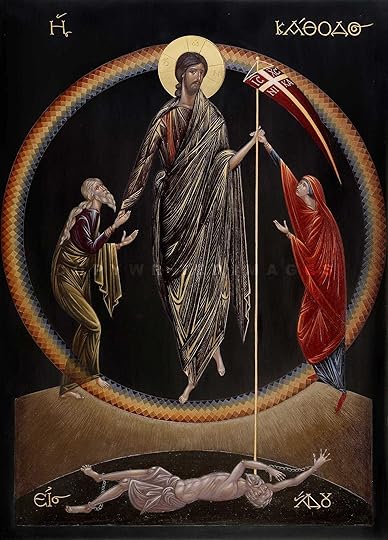

He Can Be Now No Other

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

1 Corinthians 15.29-49

There is a passage in Israel’s scriptures which reports the suffering of seven brothers. The story’s horrific brutality and grisly details recall the atrocities committed by the Russian army in Bucha only a year ago. The events narrated by the Second Book of Maccabees transpire nearly two hundred years before Mary of Nazareth gives birth to the God-who-is-human. Before Rome occupied and oppressed Israel, Greece did so under a caesar named Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Like every empire who has ever attempted to solve their self-imposed “Jewish problem,” the invading Greek regime attempted to pacify the Jews by stamping out what makes them Jews; that is, Israel’s fidelity to the Torah bequeathed to them by the true God.

In chapter seven of 2 Maccabees, Antiochus attempts to compel seven Israelites brothers, along with their mother, to violate the Jewish law. By means of torture, Antiochus presses the Jewish family to eat the most pagan of proteins, pork.

The first brother refuses.

And Antiochus immediately orders the brother’s tongue cut out, his head scalped, and his hands and feet chopped off.

Meanwhile his mom and his younger brothers look on.

Then— brace yourself— the president’s goons fry the elder brother in a human-sized cast-iron skillet.

The Greeks do likewise to the second brother, who, as his elder brother, refuses to forsake his faith. No sooner has Antiochus seared brother number two in a very large dab of butter than the third brother sticks out his tongue, freely offering it to his tormentors. Even bolder, the third brother stretches out his hands before his tormentors and he defiantly declares to them, “I got these hands from the Lord, and because of his Torah I forsake them, and from the Lord I will get them back again.”

In other words: “The God in whom I’ve kept faith gave me this body, and God, keeping faith with me, will give it back again.”

God will vindicate me.

God will deliver us.

Sin will not win.

Death will be undone.

God will give me my body back.Because the story told in 2 Maccabees takes place in the world as we have made it, the third brother’s defiant hope was just so, only hope. Brothers four, five, six, and seven, along with their faith-instilling mother, all meet the same violent and evidently incontrovertible end.

Death has the last word.

Nevertheless—

There in Israel’s scriptures stands a full-throated hope for Resurrection.

Back before I was the wise and mature man you see in front of you today, I told that story of the seven brothers (and their Mom) in a children’s sermon.

On Easter Sunday.

As you might expect, the story riveted the children as I acted it out with them. Every kid loves a story with a thoroughly wicked villain in it. I even brought along a slab of bacon, a cast-iron skillet, and a stick of butter as props. As you might also expect, some of the parents of those children responded with less enthusiasm.

I wouldn’t again tell that story to children— I’m a parent now. But I have told the story to you. I’ve done so because I want you to see what we so often omit or obscure: Resurrection is not a Christian hope.

Resurrection is not a Christian hope.Resurrection is a Jewish hope.Resurrection is a belief that belongs to Israel’s faith.And you do not need to go digging in minor, apocryphal books like 2 Maccabees to find Israel’s Resurrection hope. It’s pledged by all of Israel’s major apocalyptic prophets.

And so the prophet Isaiah proclaims that one day, when the Lord finally undoes the present scheme of things and enthrones himself as King:

“The Lord will destroy…the shroud that is cast over all peoples…he will swallow up death forever.”

In the Book of Ezekiel, the Lord surveys a valley of dry bones— the whole house of Israel, dead— and the Lord considers his promise to Abraham, asking the prophet, “Mortal, can these bones live?” Because if those bones cannot once again live, then the Lord’s foundational promise to his people is broken, for Israel has not yet been a blessing to the whole world nor have they gathered the whole world to worship with them the one, true God.

Death, therefore, is the enemy of God’s original promise to his people.

“Mortal, can these bones live?” the Lord asks Ezekiel before answering his own question with a promise:

“I am going to open your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel.”

The hope of resurrection appears again on the lips of the prophet Daniel:

“Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life..But you, go your way and rest, you shall rise for your reward at the end of days.”

God will give us our bodies back.

Resurrection is a Jewish hope.

The Gospels make this explicit when they report Jesus getting dragged into a dispute between Sadducees, who did not believe in the Resurrection, and the Pharisees— like Saul— who absolutely did believe it. As Mark writes in his Gospel:

“Some Sadducees, who say there is no Resurrection, came to Jesus and asked him a question, saying, “Teacher, Moses wrote for us that if a man’s brother dies, leaving a wife but no child, the man shall marry the widow and raise up children for his brother. There were seven brothers; the first married and, when he died, left no children; and the second married her and died, leaving no children; and the third likewise; none of the seven left children. Last of all the woman herself died. In the Resurrection whose wife will she be? For the seven had married her.”

And Jesus said to them, “Is not this the reason you are wrong, that you know neither the scriptures nor the power of God? For when they rise from the dead, they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are spiritual bodies. And as for the dead being raised, have you not read in the book of Moses, in the story about the bush, how God said to him, “I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob”?

The Lord is God not of the dead but of the living.”

It’s critical you catch the claim hiding in that last cryptic comment from Christ. God is the God of the living not the dead because God will undo death; so that, the dead will live again, now with death behind them.

God is the God of the living not the dead because eventually, one day, in the fullness of time, there will be none but the living for God to be their God.

Resurrection is a Jewish hope.

And it’s not a dead hope.

Right now, at the foot of the Mount of Olives, in the Kidron Valley, where Jesus prayed, “Father, if it be your will, remove this cup of wrath from me,” even today— so much so that Israeli municipal officials are worried about space issues— thousands of Jews are buried in graves facing the walls of the old city of Jerusalem. Why are they so buried? Because that is the place Israel anticipates God will initiate the Resurrection. Ironically, that is the place God initiated the Resurrection.

Resurrection is a Jewish hope.

The women do not venture to the tomb on the third day expecting Resurrection. But they could have.They could have expected it. Possibly, a part of them should have expected it— guessed at it, surmised it— because Easter is Israel’s hope long before it’s the church’s hope.

Easter is Israel’s hope.

Thus—

Nothing of what Paul argues here in 1 Corinthians 15 is distinctively Christian. How Paul describes the Resurrection body is how Jesus— the Jew— describes the Resurrection body in the Gospel of Mark. Nothing of what Paul argues here is uniquely Christian.

Or rather, the substance of what Paul insists upon in these verses is exactly what Saul would have believed already, back before the Lord Jesus changed his name to Paul.

Therein lies the question.If Resurrection belonged to the “assured substance of the Jewish faith,” then why did the gospel tidings of the Resurrection meet with such stubborn doubt and striking hostility?The women who run from the tomb to tell the news— they’re the church’s first preachers. They’re also the church’s first unsuccessful preachers, convincing no one. Peter peers into the empty tomb and spies Jesus’s grave clothes, neatly folded and no longer on a dead Jesus, and Peter concludes nothing. Thomas cannot even take his friends’s word for it. The two disciples on the way to Emmaus acknowledge to the stranger they meet in the street that they have heard that God resurrected Jesus. “Some women of his disciples astounded us,” they say, “They were at the tomb early this morning, and when they did not find his body there, they came back and told us that they had indeed seen a vision of angels who said that he was alive.” They’ve heard the Easter news, yet they respond just like Peter. They simply head back home.

Why?

Even in the church at Corinth—

Paul’s made it plain that he believes the cause of the deep dysfunction and rampant immorality in their congregation is their disbelief in the Resurrection. It’s true the Corinthians were pagans before they were Christians— Gentiles not Jews— but Paul’s description here in chapter fifteen of the Resurrection body is not a new or alien claim to those formerly shaped by the religion of Plato.

To the Corinthians, there should be nothing offensive or odd about Paul’s description of the Resurrection body as being no longer hindered by carnal frame.That Jesus, freed from the finitude of the flesh, had been given a spiritual body, beyond composition or dissolution, appropriate for the celestial realm, should not have been to the Corinthians so strange a story that they remained stubbornly resistant to it. Yet their lack of faith in the Resurrection was the fissure that fractured their community. Resurrection is a Jewish hope, yes. But the Corinthians should not have had such a problem receiving it.

So why?

If the promise of Resurrection was the hope at the hub of Israel’s faith, why was the proclamation of the Resurrection such a problem? They all already believed that God had promised Resurrection. They all already believed that God’s ultimate promise to Abraham hung on the promise that God would undo death. So why did the news of Resurrection, even among the pagans in places like Corinth, meet persistent resistance?

From the start!

Matthew reports that the disciples beheld the risen Jesus on the mountain in Galilee and worshipped him, but, Matthew adds, even as Jesus stood there in front of them, “some doubted.” What did they doubt? They already believed God will give us our bodies back. “I know that my brother will rise again in the Resurrection,” Martha says of Lazarus. But when it actually happens, they want their money back.

They all already believe the promise of Resurrection. But they balk at the prospect that God resurrected Jesus. Jesus is the problematic part of the claim, “God has resurrected Jesus from the dead.”All those Easters ago, after I’d told the children the story of the seven brothers, just a beat after I’d delivered the benediction, a mother, a first-time guest, came up to about three centimeters from my face, glaring all the way.

“What in the world kind of Easter story was that?” she inquired.

“Bless your heart,” I thought.

And remember, I was not then the wise and mature spiritual leader you see before you today. So I replied, in love, ““Look, lady, I don’t know if you’ve seen the movie Donnie Darko, but the Easter Bunny is creepy as all get out— he doesn’t even have story— and besides, I’ll tell you what—that story I told the kids, that’s the only Easter story worth dragging our butts out of bed on a Sunday morning.”

Speaking of butts, she looked as though I’d just given her an enema. And as she dragged her two children away, I heard her say, “Yes, honey, we’ll hunt for Easter eggs when we get home.”

Admittedly, it wasn’t the most pastoral response imaginable.

But what I told her— it’s true.

That God the Father has responded to that third Maccabean brother’s unjust suffering and the sins sinned against him and his family, that God has responded to the world we have made by raising Jesus of all people from the dead— Paul said so at the top of this chapter, if that’s not true, we’re all wasting our time.

From the very beginning, even for the disciples, the difficult part of the gospel message, “God has resurrected Jesus from the dead,” was not Resurrection. It was Jesus.

The trouble with the Resurrection is the same trouble that led to the Crucifixion. It’s Jesus.Resurrection is a Jewish hope. But what the Jews found difficult to believe is that the God of Israel would raise the crucified Jesus, not merely from the dead but to the Father’s right hand, and, in so doing, once and for all identify himself with the Man for Others.

The Resurrection body is not an alien idea for the Corinthians. But what was anathema to the pagans was the notion not only that the Eternal One would enter into time but that God would identity himself— all the way down— by a particular history, the life lived from Mary’s womb to Friday’s tomb.

This is Paul’s argument here in 1 Corinthians 15. Those who deny the Resurrection, Paul asserts, have no knowledge of God.

In other words:

To misunderstand the Resurrection is to misunderstand the gospel.To misunderstand the gospel is to misunderstand God.Because— pay attention— the Resurrection settles who God is.This is what’s at stake in 1 Corinthians 15. Just as the death of Jesus forever settles Jesus’s identity, the Resurrection of Jesus forever settles God’s identity. He can be no other now. Correlatively, this means you can never now be otherwise. By raising the Man for Others to his right hand, the Father is now forever for you.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“The Crucifixion put [the question] up to the Father: Would he stand to this alleged Son? To this candidate to be his own self-identifying Word? Would he be a God who, for example, dines with scoundrels and parties with sinners, who justifies the ungodly? The Resurrection was the Father’s Yes.

We may say: the Resurrection settled that the Crucifixion’s sort of God is indeed the one God…

Or, the Crucifixion settled who and what God is; the Resurrection settled that this God is.

And just so the Resurrection settled also who and what we are, if we are anything determinate.”

Author Marilynne Robinson’s quartet of novels take place in the fictional Midwest town, Gilead. The first novel, Gilead, is in the form of a long letter a father writes to his young son. Married late in life, the father, a pastor, knows he’s dying of cancer and so will not live to know his boy. The second novel, Home, centers around that pastor’s best friend, who is also a pastor, and his troubled family. The pastor in the second novel names his son after the pastor in the first novel, Jack.

Jack is a prodigal son. A mystery even to himself, Jack wanders and struggles and self-sabotages. Jack is perpetually restless and cannot find his place in the world. Nor can Jack muster up any mercy or forgiveness for himself.

There’s a scene in the story where, after a long and painful absence, Jack returns home from his own far country. While his son was gone from home, his father had vowed to himself that if his son ever returned home he would not lose his patience or lash out in anger.

But he does.

Jack’s father, the retired minister, says to his son:

“I promised myself a thousand times that if you ever came home you would never hear a word of rebuke from me, no matter what.”

And the prodigal son responds to his father:

“I don’t mind. I deserve rebuke.”

And the old man replies to his child:

“You ought to let the Lord decide what you deserve. You think about that too much— what you deserve. I believe that is part of the problem.”

Jack smiles and says:

“I believe you may have a point.”

Jack’s father says to him:

You ought to let the Lord decide what you deserve. The Lord has so decided.“Nobody deserves anything good or bad. It’s all grace. If you accepted that, you might be able to relax a little.”

For you. For me. For all of us. For every last sinner among us.

Because the Father has resurrected Jesus from the dead to sit at his right hand; that is, the Lord has decided to identity himself forever as the Friend of Sinners.When you think about it, we shouldn’t be too hard on all those in scripture who struggled to believe the news of the Resurrection. After all, on its face, it’s too good to be true.

If the Resurrection settles once and forever who God is, then God’s Kingdom really will be one where the poor will be blessed and the last will be first. If the Resurrection settles once and forever who God is, then there really will be many mansions in the Father’s house for all sorts of us who do not deserve them.

No wonder they didn’t believe what they’d always previously believed.

It’s too good to be true.

If the Resurrection settles once and forever who God is, then that means God’s love does not depend on what you do or what you’re like. That means there’s nothing you can do to make God love you more and there’s nothing you can do to make God love you less. That means God will never give you what you deserve and will always give you more than you deserve— it’s all grace.

If the Father identifies himself with this Son, then that means God really is like an old lady who’ll turn her house upside-down for something that no one else would find valuable, a shepherd who never gives up the search for the single sheep, a dad on the porch who never stops looking down the road and is always ready to say “we have no choice but to celebrate.”

Christ is risen. And indeed:God can be now no other God but the God who is for you.No matter what you do, no matter where you go, no matter which direction you run in your life— there’s no escape. You are always headed into the arms of his loving embrace.So come to the table.

God has resurrected Jesus from the dead.

Therefore, Jesus’s promise is trustworthy and true.

The loaf and the cup are him.

His mercy is now.

And here.

For the taking.

Thank you for reading Tamed Cynic. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 6, 2023

G(ud)-Punkten

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

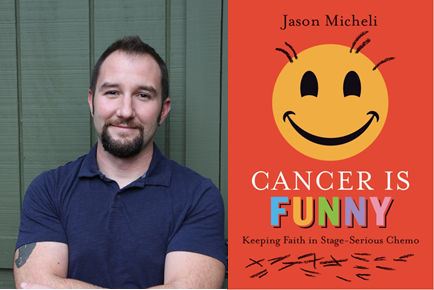

Reader/listener Monica Alhbin hosts a theological podcast in Sweden called G(ud)-Punkten. Apparently, I’ve got more fans in Sweden than Johanna Hartelius’s Dad. Monica invited me on her show a few weeks back to talk about my book, Cancer is Funny, the Crackers and Grape Juice podcast, and theology. She also showed off her improvements to our Stanley Hauerwas t-shirt.

I certainly can’t do interviews in a second language so do her a solid and check out her podcast— you’ll see we have friends in common.

May 5, 2023

Predestination is Plural

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The transition from Eastertide to Pentecost is not simply a matter of the narrative flow from Luke’s Gospel to Luke’s Book of Acts nor is it a matter of sequential chronology on the liturgical calendar. There is a logical dependence between Eastertide, when the church receives the full revelation of the Lord Jesus’s identity, and Pentecost, when the Spirit sends the church forth to gospel. As ludicrous as it sounds, the church is not merely the chosen transmitter of the gospel, she is herself, the creeds profess, part of that gospel’s content.

God has elected the church to proclaim the gospel. Likewise, God has elected the church to be an item of that very gospel.This is so because Jesus is both personally the second identity of the Triune God and what Augustine called the totus Christus within the church. The totus Christus— the whole Christ— is the Lord Jesus risen as the head of his body, the church gathered around him in loaf and cup. Therefore, if the total Christ includes his body, the church is not what the theologians have termed an opus ad extra, a work in creation outside of God. Nor does the church belong to what those same theologians refer to as the economic Trinity, the outward and visible manifestation of the Triune life.

To put it as bluntly as possible:

The church as Christ’s body is not a metaphor.

It’s a metaphysical assertion.

Because the second person of the Trinity is the totus Christus, the body of Christ, the church, is inseparable from God’s own identity.

As scripture attests, the Father alone is prior to all being. In begetting an other, the Father speaks the creative Word. In creating, the Father orders all things and directs all things to the End that is the totus Christus. All of this is the straightforward witness of scripture:

“He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and FOR him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. He is the head of the body, the church.”

The Father’s originating election mandates the church.

That is, God predestines the people called church.

This is what Robert Jenson contends when he writes:

“The unmediated and wholly antecedent will that is the Father dictates there be the church, as something other than the world or the Kingdom, and that this church be exactly the one that exists.”

The church is constitutive of God’s very own identity. This is why Karl Barth, reworking Calvinism’s notion of predestination, made the doctrine of election the hinge upon which the entire doctrine of God turns. God predestines the church. As odd as this claim may strike us, knowing as we do what a poor vessel this clay jar has proven over two millennia, it is, in fact, the foundational premise of St. Augustine’s two polities in the City of God. The church is “predestined to rule eternally with God.” The cities of this earth, by contrast, are predestined to pass away (so it’s silly for us to spend so much energy perpetuating partisan antagonisms).

In electing to be the Father of this particular Son, God predestines the church.Many have tried to render this claim less audacious by positing the so-called doctrine of the invisible church. Christ’s true body, this attempt suggests, the actual disciples versus those just going to church because their spouse makes them, cannot be discerned in this age. The desire for an invisible church is the desire for a church without sin, and, just so, Christians without need of a savior.

As Jenson jokes:

“The church is not an invisible entity; she is, if anything, the all too visible gathering of sinners around the loaf and the cup. What is invisible is that this visible entity is in fact what she claims to be, the body of Christ.”

Once again the claim: in electing to be the Father of this particular Son, God predestines the church. An implication of the dogma emerges immediately.

Predestination is plural.

And here we can glimpse just how the church invoked the doctrine of predestination as a comfort.

Predestination proclaimed the assurance, no matter what trials and tribulations afflicted the community of believers, no what losses and schisms she suffers, the church will nevertheless abide.

“The church is predestined to abide, finally in God,” Melanchthon insisted, “the world’s polities (ie, the world’s POLITICS) are predestined to perish.” Predestination, then, is absolutely not an abstract doctrine, disconnected from Jesus Christ, primarily about the fate of individuals, as though God is a cosmic sorting hat. Predestination is a concrete doctrine about the Father’s election of Jesus Christ and so of his body, the church.

Predestination names the opposite work of sorting. Predestination names the Father’s decision to gather all the motley crew whom the Son has the poor taste to call his friends.Or, as Paul puts it prettier in Ephesians, “He chose us in Christ before the foundation of the world.” Augustine said it even better, “Just this One [Jesus] is predestined, to be our head, and so many are predestined, to be his members.”

These two choosings are one event in God.In other words, Jesus, the God-who-is-human, is a decisive event in God’s own life and the church, with the very unimpressive individuals who comprise this church, is the body of the person Jesus who is the same event in God.

Once the doctrine of predestination is presented, the question always rises nonetheless, “But how do I know I am among the elect?”The fatal (and frightening) mistake made by ideas of individual predestination is that they posit a person’s predestination by God as a single event in eternity back before the actual events that comprise a person’s life, making that person’s reception of the gospel and his or her baptism into it inconsequential. However, such understandings of before and after are insufficient for the scope of the gospel’s evocation of Jesus’s pre-existence or his identity as the totus Christus.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“It is not that God has already decided whether I am or am not of his community. He will decide and so has decided; and has decided and so will decide; and so decides within created time. The eternal pre- of Christ’s existence, which is identical with the pre- of predestination, occurs also within time, as the Resurrection and as the contingency and divine agency of Israel’s and the church’s proclamation and prayer, visible and audible. Thus, to the penitent’s question, The confessor’s right answer MUST be, “You know because I am about to absolve you and my doing that IS God’s eternal act of decision about you.””

In other words, because the God who predestines is the God of the Bible, divine election is not an event lurking behind or above the event of Christ’s coming to me through the ministration of his body, the church. And that body, the church, is also the place where God applies predestination in the present. Baptism, as Luther said, is the Father’s giving of sheep to the Son’s fold.

Thank you for reading Tamed Cynic. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 4, 2023

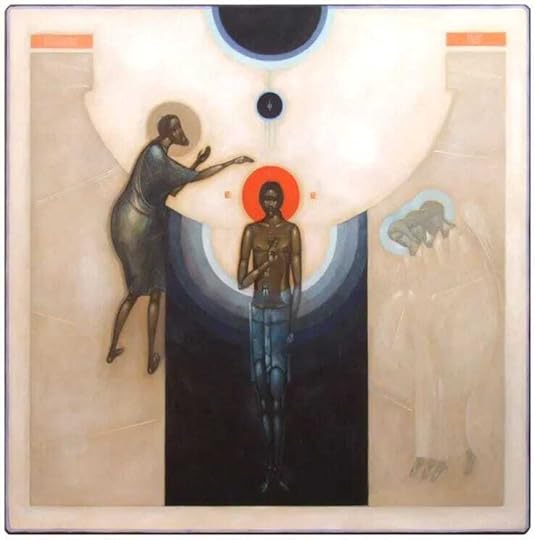

If Jesus is Risen, Where is His Body?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

One of the gospel-minimum components of the church’s resurrection proclamation poses a particular problem for believers who live after Copernicus. Modern people remain every bit as superstitious as our ancient forebears, yet the claim of Jesus’s bodily resurrection presents a difficulty for us that it did not for them. Specifically, to be a body is to be locatable. A minimum consideration to register about the body of Jason Micheli, for example, is that you can now find it, sitting comfortably with a cup of coffee, outside of Washington DC.

So then, where is the body of Jesus?

Prior to Copernicus, the church’s canon and creed provided a simple solution to this question. The Father raised the Son to sit at his right hand in heaven.

"He ascended to heaven and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty. From there he will come to judge the living and the dead."- The Apostles's CreedAs though he drank too much Fizzy Lifting Drink, the ancient church presumed the Risen Jesus gets to heaven by moving through space to the boundary of the earthly space and the heavenly one.

Heaven in scripture is the space God makes for himself within creation to be both his own dwelling in creation and his availability to his creatures there. Thus, God’s heaven was as necessarily locatable as any other corner of God’s creation. If the ancients had possessed GPS, they could have found heaven according to its coordinates in time and space.

“Copernicus,” Rudolf Bultmann demanded the faithful acknowledge, “has left us no space for heaven.” Heaven, we know, is not “up there.”We cannot honestly think or believe in heaven in the manner we have received it. If we could so think, then there would be more evangelical-subsidized rocket research.1 But neither can we afford to reduce heaven to a spiritual metaphor, for “Jesus is risen” is the sole predicate of the gospel and if Jesus now lives with death behind him, then his body must be located somewhere.

Again then, where is the body of the Risen Jesus?Even before Copernicus forced our renewed conception of the cosmos, Martin Luther, in his typically intemperate way, derided as theologically ridiculous the notion that heaven is a place or that we could gesture towards the Risen Jesus by pointing up.

Luther nevertheless remained committed to locating the body of the Risen Jesus according to spatial coordinates. In fact, the locatability of the risen Jesus’s body is at the heart of the Reformer’s dispute with his Swiss counterparts, for, however we conceive of heaven, the Bible states straightforwardly that when a sacrifice of praise is offered in his name with bread and wine there is Jesus’s body. On the table. In mouths and bellies. As locatable by Google Maps as any other item in creation.

Luther thought this matter through by distinguishing three ways of being located.

An object can be someplace “circumscribably,” where the boundaries we draw for it are its own boundaries.

An object can be someplace “definitively,” where it has no spatial boundaries but can still be located according to boundaries (eg, an idea in your head).

Or an object— actually only God— can be someplace “repletively;” that is, God is at any given place at any given moment because God is separated from no place. He may be anywhere and everywhere because in no way or place is God at all bounded.

Thus, Luther concluded, that the Risen Jesus is not located in the first way at all. That the Risen Jesus is not circumscribable at all means that he is not a particular material object. As the Gospel narratives themselves make plain, the body of the Risen Jesus is not subject to the laws of Newtonian physics. He may appear in space but is free of being located within it.

Were Jesus circumscribable, Luther argued, it would be impossible for the Risen Jesus to be in heaven while also being behind locked doors in the upper room with the frightened disciples.

It would be impossible for him to appear to me (as he did one fall day in my college years) and also to be at First Church______ as loaf and cup. He could be found in neither instance while also being located in the midst of two or three gathered in his name.

All of these locatabilities scripture requires us to stipulate. Just so, the Bible requires us to understand the Risen Jesus in the third manner.

Jesus is in the Trinity. Therefore, Jesus the man— Jesus as a body— shares in the Father’s repletive location.Happily, this move does not even require believers to disavow the dogma of the creed.

The Father in their Spirit raised the Son to sit at God’s right hand.

Where is God?

Everywhere.

Thus, Jesus is risen to sit at the right hand of Everywhere.

Copernicus actually helps us put the Bible’s claims even more clearly. The body of the Risen Jesus is omnipresent, infinitely available if not infinitely extended. The embodied God-who-is-human, Luther insisted, has all creatures as his simultaneous object; and so, he can make himself an object for us— simultaneously for all of us.

Gerard Manley Hopkins was off by quite lot. Christ plays in far more places than ten thousand.A question emerges that Luther left to faith: how can the body of the Risen Jesus be infinitely available without dividing his spirit which animates it? A disciple of Luther’s, Johannes Brenz, ventured an answer. A body, he speculated, need not be in any location in order to be a body, “for the whole creation, the great body, precisely contains all places and so is itself no place.” That is, all things are already located by the simultaneous intention of God, or as Paul says at the Areopagus, “In him we live and move and have our being.”

If Jesus is in the Trinity, then Jesus shares the Triune God’s presence as subject to all things. As for God so too for Jesus, all the places where the Risen Jesus could locate himself as a body are but one place.Still, that all people are located in but one place to the Risen Jesus does not say how we may reliably locate him. The Risen Jesus is free to vanish from his disciples’s sight on the road to Emmaus, but the Risen Jesus likewise promises that he may be found. For Luther, this is the reason for Jesus’s “definitive” presence in loaf and cup.

As Robert Jenson writes:

“Although the embodied Jesus is not bounded by spatial coordinates, he can be pointed to spatially, where— and only where— he intends us to find.”

It is Christ’s attested intention that we look to bread and wine and just so behold— and be beheld by— him.

Jesus’s repletive omnipresence is the necessary condition for Jesus’s definitive presence. According to Luther, the Risen Jesus is not circumscribable. As Paul also says in 1 Corinthians 15, there is no single material object that is the body of the Risen Christ. Thus, Luther has no anxiety about how the body of Jesus can be bread and wine (or baptism’s water or the mutuality of believers or the preacher’s proclamation).

Quite simply:Bread and wineFont and waterWord and proclaimerTwo or three gathered in his nameThese constitute all the body the God-who-is-human requires to live as God-with-us.Thank you for reading Tamed Cynic. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app1

Robert W. Jenson

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers