Jason Micheli's Blog, page 80

April 7, 2023

Mary's Son is Pilate's Victim

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paidsubscriber.

Hi Friends,

As has become my custom over the past five years, I’ve written seven homilies for Good Friday. This year I’ve taken seven of the scriptures associated with the Stations of the Cross tradition.

To avoid bombarding your inbox throughout the day, I am only scheduling this first homily to go out by email. The other six I will post throughout the day on my website. You can find them HERE.

Blessed Three Days,

JM

Pilate Condemns Jesus to Die — Mark 15.1-15, 15

In Cormac McCarthy’s novel, No Country for Old Men, the titular character Sheriff Bell reflects on the violence begat by the drug trade which he has witnessed. Sheriff Bell remarks to his wife,

“I think if you were Satan and you were settin around tryin to think up somethin that would just bring the human race to its knees what you would probably come up with is narcotics. Maybe he did. I told that to somebody at breakfast the other mornin and they asked me if I believed in Satan. I said Well that aint the point. And they said I know but do you? I had to think about that. I guess as a boy I did. Come the middle years my belief I reckon had waned somewhat. Now I’m startin to lean back the other way. He explains a lot of things that otherwise dont have no explanation.”

According to the dogma, the logic is simple if defiantly mysterious:

First, there is evil.Second, there is God.Therefore, there must be an Adversary.The tradition has ventured a little beyond this logic by describing the devil strictly by his deficiencies. After all, if the devil is not a necessary being, if Satan is not the product of God’s creative intention, then he is best known not by what he is but by what he is not. So St. Augustine named the person of Evil as “the privation of the good” while Karl Barth insisted that if Christ is known by his benefits, then the Adversary may be apprehended by his detriments. The Book of Job provides a clear example of one such parasitic detriment belonging to the Accuser. There, Satan appears as the great wit in the story— he’s truly funny, yet the joke is always at Job’s expense.

It’s likewise in Christ’s last hours.

Because, of course, the one possibility seriously countenanced neither by Pontius Pilate nor the elders, scribes, or chief priests is that the inscription they will hang over his bloodied head bears witness to the truth.

It is ironic. He is the King of the Jews. But the joke will come at Jesus’s expense. We know the devil by his detriments.

Satan explains a lot of things that otherwise do not have any explanation.

Chief among them, the fact that the Living God has an executioner. Make no mistake, the first station of Jesus’s cross is simultaneously the first of the Adversary’s final temptations of him, “Are you the King of the Jews?”

When Jesus responds to his arraignment with an answer that is as evasive as it is disinterested (“You have said so.”), the chief priests irately accuse him of “many things.” We know from Matthew’s account that these many things all amount to blasphemy. Yet Pontius Pilate— a pagan— has absolutely no stake in mediating a dispute among Jews over a charge of blasphemy. The case the chief priests have brought to him is a waste of his time. He wants to send it back down to the lower court. He’s searching for a reason to make this a Jewish problem for the Jewish priests to resolve.

Which is to say, Jesus could answer simply, “No.”

And Pilate would spare him a cross.

“Are you the King of the Jews?”

“No. No, I’m not a threat to you.”

Jesus could answer, “No, I’m not the King of the Jews.”After all, Jesus never claims to be Israel’s Messiah. Study the scriptures again. Jesus never identifies himself as the Messiah of Israel. Rather, the Father affirms him as such only by resurrecting him from the dead.

“Are you the King of the Jews?” He has not said that he is. He could say that he is not and so save himself. To be sure, therein lies the presence of the Adversary.

In the Gospel narratives, Satan appears in a two-fold capacity.

First, Satan is a tempter. Second, Satan is the power of death. Satan is the fear of death, which is death’s power.At the beginning of his ministry, Satan tempts Jesus with the Kingdom of God achieved by means other than the path that will lead him up to Golgotha. “You want the governments of the world conformed to your commandments,” the devil tempts him, “Bend the knee and they will belong to you.” At the dead end of his ministry, Satan appears to Jesus again as the fear of death, which is precisely the fear that death will take my self from me. It’s the fear that the I that I call me will forever cease to be. That the you you call me might in death forever cease to be would make you just like the devil (ie, empty), for what distinguishes the devil from all other persons is that the devil is a person without a self.

The devil is a person without a self of his own.

This is why the devil must always appear, parasitically, in the person of someone else.

On the lips of a friend or a lover.

In the passions of a political movement or in the id of an ideology.

Or, most often the case, as the voice in your head.

The same voice that surely responds to Pilate’s question with questions of his own, “Do you really want to die, Jesus? Are you sure about your Father in Heaven, certain enough to bet your life? What’s the harm in telling the man “No, I’m not the King of the Jews” and living to fight another day?”

Somehow Jesus overcomes this first of the Adversary’s final temptations proffered to him in the person of Pilate. He does not yield to the fear of death. He finds an answer that is neither cowardly nor sadistic.

Not, “Yes.”

Not, “No.”

But, “You have said so.”

Romeo Dallaire was a French-Canadian general who led the UN forces during the genocide in Rwanda. In his despairing memoir, Dallaire writes,

“After one of my many presentations following my return from Rwanda, a Canadian Forces padre asked me how, after all I had seen and experienced, I could still believe in God. I answered that I know there is a God because in Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him and I have touched him. I know the devil exists, and therefore I know there is a God.”

Scripture makes no mention of Jesus shaking Pilate’s hand. Indeed the latter makes a show of washing his hands of the former’s blood. Unlike Dallaire, however, Jesus needs not Satan standing before him in the person of Pilate, tempting him with the fear of death, to know there is God.

For Jesus is the Son.

And so the devil’s joke gets turned against him.

Because if Jesus is in the Trinity…Then the Father is even more there than the devil. Present with him, for him, at his left hand, as he is condemned unto death.Jesus before Pilate, therefore, shows forth what it means for us to pick up our crosses and follow him. To bear the cross is to trust that we can attempt to be faithful because the Father who is at the Son’s left hand is also necessarily at the side of all who are in Christ.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 6, 2023

Jesus is the Worst Sinner

Here’s a piece I wrote for Mockingbird for Holy Thursday:

Every year during Passover week, Jerusalem would be filled with approximately 200,000 Jewish pilgrims. Nearly all of them, like Jesus and his friends and family, would’ve been poor. Throughout that holy week, these hundreds of thousands of pilgrims would gather at table and temple and they would remember. They would remember how they’d once suffered bondage under another empire, and how God had heard their outrage and sent someone to save them.

They would remember how God had promised them, “I will be your God and you will be my People.” Always.

They would remember how with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm God had delivered them from a Caesar called Pharaoh. Passover was a political powder keg, so every year Pontius Pilate would do his damnedest to keep Passover in the past tense. At the beginning of Passover week, Pilate would journey from his seaport home in the west to Jerusalem, escorted by a military triumph, a shock-and-awe storm-trooping parade of horses and chariots and troops armed to the teeth and prisoners bound hand and foot. All of it led by imperial banners that dared as much as declared “Caesar is Lord.”

So when Jesus, at the beginning of that same week, rides into Jerusalem from the opposite direction there could be no mistaking what to expect next. Deliverance from enemies. Defeat of them. Freedom. Exodus from slavery. How could there be any mistaking, any confusing, when Jesus chooses to ride into town — on a donkey, exactly the way the prophet Zechariah had foretold that Israel’s King would return to them. Triumphant and victorious, just before he crushes their enemies. There could be no mistaking what to expect next. That’s why they shout “Hosanna! Save us!” and wave palm branches as they do every year for the festival of Sukkot, another holy day in the fall when they recalled their exodus from Egypt into the wilderness and prayed for God to send them a Messiah.

The only reason to shout Hosanna during Passover instead of Sukkot is if you believed that the Messiah for whom you have prayed has arrived.

There could no mistaking what to expect next.

That’s why they welcome him with the words “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel” the very words with which God’s People welcomed Solomon to the Temple. The same words Israel sang upon Solomon’s enthronement. Solomon, David’s son. Solomon, the King. There could be no mistake, no confusion, about what to expect next. Not when he lights the match and tells his followers to give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar (i.e., absolutely nothing). Don’t forget, Jesus was carrying the coin in question in his pocket.

There could be no mistaking what to expect next.

Not when he cracks a whip and turns over the Temple’s tables as though he’s dedicating it anew — just as David’s son had done. Not when he takes bread and wine and with them makes himself the New Moses. And not when he gets up from the Exodus table, and leads his followers to, of all places, the Mount of Olives.

The Mount of Olives was ground zero. The front line. The place where the prophet Zechariah had promised that God’s Messiah would initiate a victory of God’s People over the enemy that bound them.

From the parody of Pilate’s parade to the palm leaves, from the prophesied donkey to the shouts of hosanna, from Solomon’s welcome to the exodus table to the Mount of Olives everyone in Jerusalem knew what to expect. There could be no mistaking all the signs.

They knew how God was going to use him.

He would be David to Rome’s Goliath. He would face down a Pharaoh named Pilate, deliver the message that the Lord has heard the cries of his People and thus says he: “Let my People go.” As though standing in the Red Sea bed, he would watch Pilate and Herod and all the rest swallowed up in and drowned by God’s righteousness. God’s justice.

They knew how God was going to use him.

And when Jesus invites Peter, James, and John (the same three who’d gone with him to the top of Mt. Horeb where they beheld him transfigured into glory) to go with him to the top of the Mount of Olives these disciples probably expect a similar sight.

To see him transfigured again. To see him charged with God’s glory. To see him armed with it.

Armed for the final and decisive battle. The battle that every sign and scripture from that holy week has led them to expect.

Except —

There on the top of the Mount of Olives Jesus doesn’t look at all as he had on top of that other mountain. Then, his face had shone like the sun. Now, it’s twisted into agony. Then, they’d seen him dazzling white with splendor. Now, he’s distraught with doubt and dread. Then, on top of that other mountain, Moses and the prophet Elijah had appeared on either side of him. Now, on this mountaintop, he’s alone, utterly, already forsaken, alone except for what the prophet Isaiah called the ‘cup of wrath’ that’s before him. Then, God’s voice had torn through the sky with certainty “This is my Beloved Son in whom I am well-pleased.” Now, God doesn’t speak. At all.

So much so the theologian Karl Barth says,

Jesus’s prayer in the Garden doesn’t even count as prayer because it’s not a dialogue with God.

It’s a one-way conversation.

It’s not just that God didn’t speak or answer back, God was entirely absent from him, as dark and silent to him as the whale’s belly was to Jonah.

There, on the Mount of Olives, Peter, James, and John, with their half-drunk eyes, they see him transfigured again.

This would-be Messiah who’d spoken bravely about carrying a cross, transfigured to the point where he’s weak in the knees and terrified.This would-be Moses who’d stoically taken exodus bread and talked of his body being broken transfigured so that now he’s begging God to make it only a symbolic gesture. This would- be King who can probably still smell the hosanna palm leaves transfigured until he’s pleading for a Kingdom to come by any other means.

Peter and the sons of Zebedee, they see him transfigured a second time.

From the Teacher who’d taught them to pray “Thy will be done …” to this slumped-over shadow of his former self who seems to pray against the Father’s will.

Jesus had boldly predicted his betrayal and crucifixion. Now he’s telling his disciples he’s “deeply grieved and agitated.” Or, as the Greek inelegantly lays it out there, he tells them he’s “depressed and confused.” Jesus essentially tells the three: “Remain here with me and stay awake, for I am so depressed I could die.”

And then Jesus can only manage a few steps before he throws himself down on the ground, what Matthew describes as ekthembeistai, meaning to shudder in horror, stricken and helpless. He is, in every literal sense of the Greek, scared out of his mind. Or as the Book of Hebrews described Jesus here, crying out frantically with great tears.

He is in the garden exactly as Delacroix depicted him: flat in the dirt, almost writhing, stretching out his arms, anguish in his eyes, his hands open in a desperate gesture of pleading.

God’s incarnate Son twisted into a golem of doubt and despair.Transfigured. As though he’s gone from God’s own righteousness in the flesh to God’s rejection of it.

God’s incarnate Son twisted into a golem of doubt and despair.Transfigured. As though he’s gone from God’s own righteousness in the flesh to God’s rejection of it.Peter, James, and John, the other disciples there on the Mount of Olives, any of the other pilgrims in Jerusalem that holy week — they’re not mistaken about what should come next. They weren’t wrong to shout “Hosanna!” They’re all correct about what to expect next. The donkey, the palm leaves, the Passover — it all points to it, they’re right. They’re all right to expect a battle.

A final, once for all, battle. They’re just wrong about the enemy. The enemy isn’t Pilate or Herod, but the One Paul calls the Enemy.

The Pharaoh to whom we’re all — the entire human race — enslaved isn’t Caesar but Sin. Not your little “s” sins but Sin with a capital “S,” whom the New Testament calls the Ruler of this World, the Power behind all the Pharaohs and Pilates and Putins. They’re all correct about what to expect, but their enemies are all propped up by a bigger one.

A battle is what the Gospel wants you to see in Gethsemane. The Gospel wants you to see God initiating a final confrontation with Satan, the Enemy, the Powers, Sin, Death with a capital “D-,” the New Testament uses all those terms interchangeably, take your pick. But a battle is what you’re supposed to see.

Jesus says so himself: “Keep praying,” he tells the three disciples in the garden, “not to enter peiramós,”

The time of trial. That’s not a generic word for any trial or hardship. That’s the New Testament’s word for the final apocalyptic battle between God and the Power of Sin (cf. 1 Pet 4:12). The Gospels want you to see in the dark of Gethsemane the beginning of the battle anticipated by all those hosannas and palm branches.

But it’s not a battle that Jesus wages.

Jesus becomes its wages.

That is, the battle is waged in him.

Upon him.

From here on out, from Gethsemane to Golgotha, the will of the Father and the will of Satan mysteriously coincide in him:

The will of Sin to reject God forever by crucifying Jesus.

The will of the Father to reject Sin forever by crucifying Jesus.

In the garden, Jesus is confronted by two opposing wills that act in a hideous union. In the garden, the line between good and evil inseparably blurs beyond recognition. Which way is the path of the righteous and which is the path that leads to Sheol? Before him lay nothing but the way of Godforsakeness.

That’s the shuddering revulsion, the fear and trembling that overwhelms Jesus in Gethsemane: The realization breaking over him that the will of the Father will be done as the will of Satan is done.In him, upon him, “thy will be done” will be done for both of them, his Father and his enemy, on Earth as in Heaven and in Hell.

But Jesus does not withdraw and flee to the western wilderness. He accepts that he will be the concrete and complete event of God’s rejection of Sin. He agrees to be made vulnerable to the Power of Sin and God’s judgment of it. He consents to absorb the worse that we can do, as slaves to Sin. And he consents to absorb the worst that God can do- the worst that God will ever do. As Paul puts it in 2 Corinthians 5, “For our sake, God made him to be Sin who knew no sin.”

He who was without sin was transfigured into sin.

Recently a college student in my parish sent me a link to a Washington Post story about children being tortured in Ukraine by invading Russian soldiers. After the link, all the student wrote in her email, “What do Christians say?!”

What do we say?

Something trite about God’s love?

Maybe because we’ve turned God’s love into a cliche, or because we’ve so sentimentalized what the Church conveys in proclaiming “God loves you,” but many people assume that Christians are naive about the dark reality of sin in the world. But we’re a people who place a torture device on top of our buildings. We’re not naïve — neither about the cruelties of which we’re capable, nor the dreadful seriousness God deals with those cruelties.

What do Christians say about the evil of the world?The dread, final, righteous, wrath-filled “No” God speaks to Sin.And the nevertheless “Yes” God speaks to his enslaved sinful creatures. The “Yes” God in Christ speaks to drinking the cup of wrath to its last drops.

The apostle Paul says that in Christ God emptied himself, taking the form of a servant. In Gethsemane, Christ empties himself even of that. He empties himself completely, pours all of himself out such that, as Martin Luther says:

When Jesus gets up off the ground in Gethsemane there’s nothing left of Jesus.

There’s nothing left of his humanity.

He’s an empty vessel; so that, when he drinks the cup of wrath he fills himself completely with our sinfulness.

Jesus isn’t just a stand-in for a sinner like you or me. He isn’t just a substitute for another. He doesn’t simply become a sinner or any sinner.

He becomes the greatest and the gravest of sinners.It isn’t that Jesus dies an innocent among thieves. He dies as the worst sinner among them. The worst thief, the worst adulterer, the worst liar, the worst wife beater, the worst child abuser, the worst murderer, the worst war criminal. Jesus swallows all of it. Drinks all of it down and, in doing so, draws into himself the full force of humanity’s hatred for God.

He becomes our hatred for God.

He becomes our evil.

He becomes all of our injustice.

He becomes Sin.

Upon the cross Jesus does not epitomize or announce the Kingdom of God in any way. He becomes the concentrated reality of everything that stands against it.

He is every Pilate and Pharaoh. He is every Herod and Hitler and Putin, every Caesar and every Judas. Every racist, every civilian casualty, every act of terror, and every chemical bomb. All our greed. All our violence. Every ungodly act and every ungodly person.

He becomes all of it.

He becomes Sin.

So that God can forsake it.

Forsake it.

For our sake.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 5, 2023

Judas: Icon of the Merciful Depths of the Crucified Love of the God Who is Human

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Traditionally, the Wednesday of Holy Week recalls Judas’s betrayal of Jesus.

After stooping down like a slave and washing his disciples’s feet, Jesus breaks news of a betrayer. "Very truly, I tell you,” Jesus announces, "one of you will betray me.” Peter asks Jesus, "Lord, who is it?” And Jesus answers enigmatically, "It is the one to whom I give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish." Jesus then dips the piece of bread, hands it over to Judas son of Simon Iscariot, and says to him, "Do quickly what you are going to do.”

John reports that immediately thereafter “Satan entered into Judas.”

Two or three hours later, Judas leads a torch-carrying mob of religious officials to the garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives where Jesus is praying. The chief priests and the Pharisees have been hunting Jesus for over a week. They first plotted to kill him after Jesus raised Lazarus from the grave.

At the Fall, in the garden, God went searching for Adam, whose sin had caused him to hide in shame. “Adam, where are you?” the Lord had asked. On the eve of redemption, sinful Adam comes searching for God who is hiding in plain sight, naked and unashamed, in a homeless carpenter. “We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth,” we say. After he walked on water, when Jesus taught in the Temple and upset more than tables and cash registers, John reports that “No one was able to lay a hand on Jesus because his hour had not yet come.”

But when his hour does come, when the betrayal of Judas leads these begrudgers through the darkness of night to the light of the world, Jesus voluntarily and deliberately gives himself up. The one who has preached peace does not resort to violence in order to resist them.

He identifies himself.

No— he reveals himself.

“We’re looking for Jesus of Nazareth.”

Jesus responds with his final I AM saying. And this last self-attestation is as stripped down and bare as he soon will be upon the cross. “I AM,” announces. And immediately, John writes, Judas and the lynch mob stumble backwards and fall to the ground. They understand. One is not bold in an encounter with God.

“I AM.”

Ego eimi.

As Fleming Rutledge says:

”This is the climax of the I AM sayings, and, really, it cannot be construed as anything other than a deliberate appropriation by Jesus of the name given by God to Moses from the burning bush. Therefore, precisely at the moment when his passion begins, Jesus unequivocally identifies himself as nothing less than the living presence of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the creator of the universe, the Lord who is and who was and who is to come.”

Martin Luther compressed the mystery of this culminating I AM saying with the Latin phrase Finitum capax infiniti:

“The finite is capable of containing the infinite.”This messiah contains more than multitudes. In the end, what holds the Bible together are neither propositions nor pictures but a person. Scripture’s constellation of recurring images (garden, tree, water, blood, bread, light, vine and door) all terminate in a single, singular icon— the God who is human.

The only instance where Jesus says or does something in John’s Gospel that does not end with someone believing in Jesus is in Gethsemane standing before Judas and the thugs about to bind him.

After stumbling backwards and falling to the ground, Judas runs away.

He returns the thirty pieces of silver to the ones who bought him. And then he enters a passion of his own in a place the priests later named Akeldama, Field of Blood [Money].

Where Jesus gives up his life upon a tree, Judas takes his life upon a tree.Where Jesus surrenders his life believing the Father will vindicate him, Judas forsakes his life upon a tree believing there was no longer any hope for him.April 4, 2023

Psalm 22, Jesus's Cry of Forsakenness, and the Triune Life

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over all the land until the ninth hour. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” that is, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

— Matthew 27.45-46

Fill in the blanks:

If I say, “The Lord is my shepherd...”

You say___________.

If I say, “Yea though I walk in the valley of the shadow of death...”

What do you say next?

“Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and______”

And what?

If I say, “Just a small town girl/Livin' in a lonely world/She took the midnight train going _______”

You know to say, “…anywhere” before moving on to sing about a city boy and singer in a smokey bar.

Almost everyone knows the Twenty-Third Psalm by heart. It’s like “Don’t Stop Believin” by Journey. You hear it everywhere— certainly almost every time someone dies. So what would Matthew have us make of this line from Psalm 22 when Jesus dies, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Does Jesus stop believing on the cross? But Jesus is in the Trinity. Even on the cross, especially on the cross, Jesus is in the Trinity.Jesus is truly God and truly Human, without division or mixture, without— we should remember during Holy Week— an off switch for either of his two natures.

Even on Golgotha he still is God.

Does Christ’s cry of dereliction suggest that Jesus believes God has abandoned him?

Again, Jesus is in the Trinity. God just is the relationship between the Father and this Son in their Spirit. There is no other God but this relation.Thus, there can be no God who abandons this Son.

Nor can there be a Son who would believe the Father would abandon him.

Quite simply, a Son who would believe the Father has forsaken him would mean something far more troubling; namely, the true God does not exist.

What then do make of Christ’s cry of dereliction?

April 3, 2023

“For those who want to save their life will waste it..."

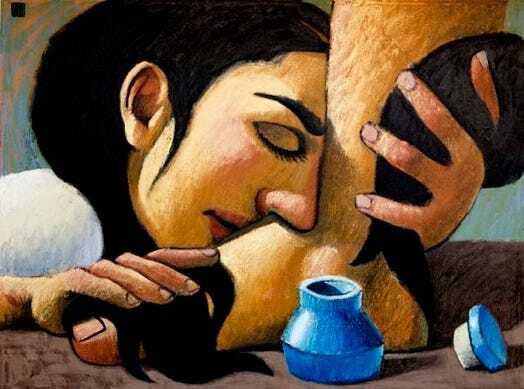

For Monday of Holy Week, the assigned lectionary Gospel is from John 12 where Mary, sister of the recently four-days-dead Lazarus, anoints Jesus with a couple of tuition payments’s worth of Chanel No. 5.

Judas et al recoil at the waste.

In Matthew’s version of the anointing, Jesus tells his disciples:

“For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.”

The specific audience for this comment is Peter, whom Jesus has called “Satan” for tempting Jesus with a future other than a cruciform destiny.

Perhaps because Jesus’s statement about our needing to lose our lives in order to gain them occurs within the context of Peter balking at the notion of a crucified Messiah we mishear Jesus as suggesting that we too must seek a cross if the Kingdom is to be added unto us.

But the Risen Christ is no nihilist.When Jesus says we must lose our lives to gain them, he’s not recruiting kamikaze Kingdom warriors, for the word “lose” in Matthew is the same word Matthew uses just after Jesus tells us about the sheep and the goats.

The word “lose” is the same word in Greek for “waste.”

ἡ ἀπώλεια αὕτη

apoleia

“For those who want to save their life will waste it, and those who waste their life for my sake will find it.”

April 2, 2023

Dying is a Part of Living

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

My oldest son, Alexander (above), keynoted a fundraising gala last night for Camp Kesem, a summer program at William and Mary for children whose parents have cancer.

Last night was also the time the Orthodox Church names “Lazarus Saturday,” in which Jesus’s work of raising Mary and Martha’s brother from the dead tips inexorably into God’s own headlong descent to a grave of his own.

In his remarks, Alexander shared that he thinks of our family’s story according to the demarcation Before Dad Got Sick and After God Sick. It’s a permanent pivot for me too as I now think of the Lenten journey generally and Holy Week specifically in terms of what it means for us who suffer to participate in the sufferings of Christ. This time of year, several years ago, as I recovered from emergency surgery and braced myself for a year of what turned out to be arduous chemotherapy et al, I pondered the humiliation that occasions illness and how it all might be comprehended according to Christ.

After all, as Christ’s passion story shows us clearly— one of the reasons they're the bulk of the Gospel narratives:Dying is a very big part of living; that is, how we die is a part of how we lived our life.I wrote then:

A few days into cancer, however, was plenty of time for me to learn that humiliation is one of the ways stage-serious cancer manifests itself:

• Needing help to pee into the plastic jug because you don’t have the ab muscles to do even that for yourself

• Needing help to change your gown at three o’clock in the morning because—fun fact—night sweats are one of the symptoms of the cancer that’s now coursing through your marrow.

• Needing the surgical resident to pretend she doesn’t notice the crack in your voice and the tears welling up around your eyes as she asks how you’re doing

As surely as a cold begets a runny nose, this cancer had brought humiliation into a life where ironic pretense and playing it cool had been the norm. For example, the third or fourth night in the hospital, the nurse, who was about to check my vital signs in the middle of the night, was standing there in the dark just as I woke up suddenly, crying and breathless from the first of what would become regular panic attacks. She wiped the sweat from my forehead, tucked me in, and shushing me, said, “It’s going to be all right, sweetie.”

Like I was a child.

A pitiable child.

In those first few days, I heard from lots of people, and many of them asked me what it’s like, having this giant steaming pile of crap land in the middle of my life. And honestly, the first word that came to mind was humiliating.

Susan Sontag, who died of cancer herself, wrote, “It is not suffering as such that is most deeply feared but suffering that degrades.”

It was the beginning of Holy Week, the time when Christians imitate Jesus’ journey to the cross, so perhaps the question would’ve struck me even if I hadn’t gotten sick, but with cancer, the question certainly felt more relevant.

Here’s the question:

• Does Christ participate in our suffering and humiliation?

• Or do we participate in Christ’s suffering and humiliation?

If the answer is the former, then that means there is no permutation of our humanity in which Christ has not been made present. Whatever we go through, the theological line continues, we can go through it knowing our suffering is not unknown to God. God, like Bill Clinton, feels our pain.

There’s nothing wrong with that answer, I suppose. But suddenly, I found good news in the latter. We participate in Christ’s suffering and humiliation by our own. Just like the bumper sticker, a lot of people treat Jesus as though he’s the answer to our problems and questions: How can I be saved? Why do bad things happen to good people? How can I find prosperity?

But if we participate in Christ’s humiliation and suffering through our own, then that means Jesus isn’t an answer to our problems and questions. Rather, Jesus gives a means of living amidst life’s problems and questions.

Can you feel the distinction? Ever since that night I had to swallow my pride and ask the nurse to help change me, I could feel the distinction. Feeling humiliated on an almost hourly basis, I didn’t need or want a God who could feel my humiliation, who shared my pain. I needed, desperately wanted, a God whose own life can show me a way to live in and through it.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 1, 2023

Hitmen and Midwives

I’ve started a new series talking about preaching with preachers and those who suffer preachers. My friend Dr. Ken Jones have kicked off the project by discussing what we’re calling the 9.5 Theses on Preaching.

In this installment, we talk about Thesis #3:

Preaching is not to be equated with the presentation of information about the Bible, a psychologica…

March 31, 2023

Hitmen and Midwives

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I’ve started a series of conversations on preaching with preachers and those who listen to preachers. Here’s Ken Jones on the third of our 9.5 Theses on preaching.

Thesis 3:

Preaching is not to be equated with the presentation of information about the Bible, a psychological examination of people’s motives, or moral exhortation for the amendment of life, for while these things are useful they cannot create saving faith.

"Work with your salvation in fear and trembling" is the better way to hear it

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Philippians 2.5-11

Notice the formal pattern of the Christ Hymn, assigned for this Sunday’s Palm/Passion readings, with which the Apostle Paul pleads for unity in his embittered and divided congregation at Philippi.

The pattern of the hymn is threefold:

Election, Condescension, Exaltation.Essentially, the pattern of the hymn is Up-Down-Up.

The Eternal Son is in the form of God and equal with God. The Eternal Son therefore is God, yet the Eternal Son elects to empty himself, sings the hymn. Veiled in flesh, our Lord conceals his majesty in the form of a slave, and by a “slave,” Paul means a slave of Sin and Death. That is, the One who, from dust, breathed into Adam the breath of life assumed the form of Adam. God, Luther said, loves to hide behind his opposite.

Up—Down—

“For us and for our salvation,” the Nicene Creed professes, the One through him all things were made, “came down from heaven…he became incarnate…and was made human.”

In the Crucified Son, our Lord shows himself to be an abolitionist. No matter what you may have heard about God loving us just the way we are, the Word of God bears witness that the Living God does not tolerate sin.

The Living God does not compromise with sin.Unlike us, the Living God does not call evil “good.” Whatever under the forms of Sin and Death enters into conflict with can have no future with God. The “appointed means of their abolition” is the Crucified Son. By his obedience, Adam’s disobedience is revoked; by his death Adam’s death is undone; and by his submission to the cross, the condemnation of the primal sinner, and so of the whole human race, is reversed and overturned. As John Calvin notes of this today’s text, “Christ is much more powerful to save, than Adam was to destroy.” Or, as we sing at Christmas, he’s “born that man no more may die.”

Up— Down— Up—

After he completes his work of perfect obedience, the Crucified Son is vindicated by the Almighty Father. He is raised from the dead and returned to glory. The Eternal Son is returned to the Father as the Crucified Son where he is now and forever the Exalted Son.

Christ’s ascension is a sort of incarnation in reverse.Just as the Eternal Son crosses over into Sin and Death without ceasing to be God, so now the Crucified Son crosses over from earth to heaven without ceasing to be human.

This is important—

The form the Son takes on earth, the form of a crucified slave, he takes that form with him to sit at the right hand of the Father. The Crucified Son brings his humanity with him into the very being of God. Which means, he brings you with him, in him, back to God. As Jesus said, “No one comes to the Father except by me… If truly you know me, you will know my Father as well.”

I draw your attention to the Up—Down—Up plotting of Paul’s Christ Hymn because just as it has a threefold pattern to it, so too, does the Apostle Paul use our text today to display the three different tenses of salvation.

The hymn has three movements—

Up—Down—Up.

The Eternal Son, the Crucified Son, and the Exalted Son.

Likewise, the Son’s work of salvation has three tenses—

Past, Present, and Future.

Salvation is not simply something lying on the horizon of the future the outcome of which is still up in the air. Salvation is not merely a finished and completed work, done by Jesus a long time ago in a Galilee far, far away that you only need accept.

On the contrary, salvation has three tenses.

The past tense, the future tense, and the present.

The Christ Hymn explicates the past and the future aspects of God’s work of salvation.In the past tense, salvation is a finished and complete work without remainder. Indeed, this is the primary mode in which scripture speaks of salvation.

“Because the one man has died for all,” the Apostle Paul writes to the Corinthians, “all have died to sin.” Christ Jesus, our Great High Priest, has sat down, the preacher of Hebrews declares, for he has made a blood offering of himself, a perfect sacrifice— the sacrifice to end all sacrifices.

Salvation is past tense.

The Lamb of God, slain from before the foundation of the world, has taken away all the sins of the world. There is therefore now no condemnation, Paul rejoices in Romans 8. There is no condemnation on account of the merit of Christ’s perfect obedience to the point of death— even death on a cross.

Salvation is past tense.It is finished, Jesus says, breathing his last.Salvation has been accomplished for you, already, on Calvary. Even now, salvation has been realized, apart from you in Christ and done outside of you by Christ. Atonement has been made. Once for all. You are forgiven and free— “free of the record of debt that stood against you with its legal demands. Christ set it aside, nailing it to the cross,” Colossians says. For Christ’s sake, you have been justified— you have been reckoned with Christ’s own permanent perfect record. The wages of your sin have been paid with his death. You have been saved.

Karl Barth says the past tense of salvation is better understood as an “eternal perfect” tense in that the cross of Jesus Christ is a work in the past whose effects carry forward ceaselessly for others.

Salvation is already, but salvation is also not yet.It’s future tense too.Look again at the crescendo of Paul’s Christ Hymn.

The Crucified Son has been given the name that is above every name. The name that is above every name is the name first revealed to Moses from the Burning Bush. The name that is above every name is the divine name deemed too holy for Israel ever to utter it aloud.

However, the time is coming when even the rocks will cry out, praising Christ with that unutterable name.Every knee will bow at its utterance, Paul writes, and every tongue will confess that Jesus is Lord. In fact, as the Apostle Paul makes clear in his Letter to the Romans, the future tense of salvation is cosmic in scope:

“The whole creation waits with eager longing…in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of God.”

Now, you don’t need a preacher to point out how it seems the whole of creation is still, as Paul puts it, groaning in labor pains. And certainly, there are more than a few who still have not taken a knee before Christ our Lord. Everywhere in the West we are told the Church is in decline and the Gospel is in retreat.

We can all feel the extent to which the “not yet” aspect of salvation abides.It has a future tense. God will be all in all. What is already accomplished— the fact that you are in Christ Jesus, right now, your life hid with God— will one day be actualized in glory. What is already real because of Christ’s past and finished work— the forgiveness of all your sins and the gifting of Christ’s own righteousness— will be revealed upon his return.

But in the meantime, there’s the “meantime.”

There's a third tense, there’s the present tense.

My mentor and muse, the Reverend Fleming Rutledge, writes about attending a weekday Evening Prayer service in a large Episcopal parish while she was traveling on a preaching and speaking tour. The service of Evening Prayer was led by lay people, and it included, Fleming observes, a very instructive mistake.

During the service, an older woman came forward to read the scripture lesson. The woman looked like your archetypal Episcopalian: a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, born and bred for propriety and rectitude, with, no doubt, a husband straight out of a John Updike novel. The scripture lesson that evening was our biblical text for today, a section of Chapter Two of Philippians. The woman came to verse thirteen, Fleming says, and with great solemnity began to read it:

"Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling ..." and then she stopped.

“She didn't just drift off,” Fleming notes, “as if she had lost her place or forgotten something. She came to a full stop deliberately, emphatically, at the comma, instead of the period. If she had shaken her finger at us, it couldn't have been more clear; it was an order from her to us. It was as if she were saying, "I've worked out my salvation, now you work out yours, and it had better be with plenty of fear and trembling!” It would have been funny if it hadn't also been so serious.”

Fleming writes that after the service was over, she crept up to the front of the sanctuary and took a peek on the massive lectern at the Bible from which the woman had read the scripture.

She wondered if perhaps the passage had been marked out incorrectly.

March 30, 2023

Transfiguring Repentance

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Here’s the latest session with Chris Green and the gang, discussing the repentance chapter in his book, Being Transfigured.

Here’s the prayer from St. Isaac Chris mentions in the session:

My flesh-and-bone God,

You wept over Lazarus—

let me weep over you.

Let your feet, nailed to the tree,

make my feet like the feet of a deer.

Let your hands, stretched out in death,

teach my hands to war.

Let your head, bowed in death,

lift up my head.

Let your mouth, filled with gall,

fill my mouth with songs.

Let your face, bruised and spat upon,

brighten my eyes.

By your passion, cure my passions.

By your wounds, wound my heart.

By your blood, purify my heart.

Again and again, I forsake you—

do not forsake me.

I’m a sheep lost in the wilds—

bear me home in your arms.

Feed me by the still waters of your mysteries.

Hide me in the shelter of your heart,

the secret place of the Most High.

Make my heart a home for your holy family,

a throne for you and all with whom share it.

May I become worthy of the way you see me .

Now and unto the ages of ages.

Amen.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers