Jason Micheli's Blog, page 78

April 21, 2023

Q: Does Belief in God the Creator Require Rejecting Science?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. For access to all the posts, including projects like this catechism, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

11. Does Belief in God the Creator Require Rejecting Science?Only if you mistake what Christians mean by the word “Creator.”

Theology and Science name different answers to two different questions:

Science aims to answer the question, “Why is the universe the way that it is?”

Theology, on the other hand, seeks to answer the question, “Why is there creation at all? That is, why is there something instead of nothing?”

This last question is not a question that can be answered from within the bounds of the material universe and so it is a question necessarily beyond science’s explanatory power. Thus, science, rightly understood, can never shed itself of theology.

God is theology’s answer to the question, “Why is there something instead of nothing?”

Theology and science are thus two different discourses, and the latter is beneficial to the former because it “complicates us open.” For example, a Copernican understanding of the universe complicates our construal of Christ’s ascension and even the nature of heaven.

While belief in God as Creator does not require the rejection of science, theology and science are two distinct discourses that will narrate created reality in different, sometimes conflictual, ways.

The doctrine of creation, for instance, rules out two false images of created reality: mechanism and cosmos.April 20, 2023

The Risk of Sounding Odd

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“You have been born anew, not of perishable but of imperishable seed, through the living and enduring word of God.”

— 1 Peter 1.17-23

Several months into the covid-19 pandemic, the historian Tom Holland wrote an op-ed for the British newspaper, The Telegraph, entitled, “Church leaders should not be talking like middle managers in this time of crisis.”

Though Holland’s most recent book, Dominion, is about how the Christian revolution remade the world, he’s reluctant to describe himself as more than a cultural Christian. While Holland is reticent about what he himself believes, he’s clear about what he thinks the Church should believe and profess— especially during a pandemic.

Holland notes how the Christian confession of God taking on the flesh of a poor, crucified carpenter so transformed the ancient world’s attitude toward the poor and the weak, imbuing with divine image-bearing dignity and worth, it gave rise to hospitals, nursing, and medical care as we know them today. Prior to the Gospel, Roman hospitals had existed solely to segregate slaves and soldiers in their sickness. In Christendom, however, no longer was the compassion of doctors and nurses a privilege of the affluent. “The National Health Service has its roots sunk deep into Christian soil,” Holland writes in The Telegraph:

“Nevertheless, there is a paradox. Over the course of the millennia, the Church’s teachings on the obligation of the rich and healthy to care for the poor and sick have proven so successful that they no longer depend on the Church itself. Its ancient sense of mission – to care for the vulnerable and the weak – has been largely subsumed within the welfare state.”

Like many aspects of our calling, the unique vocation once performed by ordinary Christians— in this case, caring for the victims of plagues— has been outsourced.

The theologian Stanley Hauerwas often jokes that you need only look at the architecture of Duke Medical School to know that, even for Christians, doctors are now our new priests. After all, hardly any churchgoer any longer believes an inadequately trained pastor could jeopardize their salvation, but they do think an inadequately trained physician could kill them.

Holland echoes the point in his op-ed, “The National Health System is now the object of our reverence."

But that hospitals are our new cathedrals does not mean the Church is redundant. At least, it shouldn’t be:

“The welfare state can provide care for the sick, but it cannot provide what Christianity, over the course of the past 2,000 years, has provided to so many countless people, and to such transformational effect.”

Therefore, by rights, the sweep of coronavirus should have presented Christian leaders with an opportunity. However this opportunity, Holland argued in his op-ed, was one that “all the mainstream churches seemed to be fumbling.”

Preachers and church leaders, in Holland’s judgment, sound more like the Public Health Department. Rather than the promises of providence and resurrection, the Church too often doles out reminders about hand-washing and bending the curve. If ever there were a time for the churches to speaking to a grieving and anxious people of “how the dead will rise into the blaze of eternal life, a time of global pandemic would surely seem to be it.”

“Parroting the slogans of the Department of Health and Social Care may conceivably help save lives,” Holland writes, “but it seems unlikely to win many souls.”

It is not the care of souls.

That is, it is not the peculiar work to which we have been elected.

We uniquely exist to proclaim a particular word— the word beyond the last word, the word which Peter proclaims in the lectionary epistle for the Third Sunday of Eastertide: “You have been begotten anew through the living and abiding Word of God, Jesus Christ.”

The apostle Peter’s epistle is an extended exhortation— a summons for the Church to take up, dwell in, and live out its identity as those elected by God in Jesus Christ, chosen to bear witness to the Risen Lord’s cruciform way in the world. Now, keep in mind, the apostle Peter wrote to his scattered churches during the imperial reign of Nero, a Caesar whose cruelty towards Christians earned him a numeric nickname by St. John, 666.

Needless to say, those Christians addressed by Peter lived during a time when the temptation was ever present to dilute their particular and peculiar calling. Peter would not feel compelled to exhort believers to hold fast to their vocation to embody the New Age inaugurated by cross and resurrection if some believers were not at risk of letting go of it.

Let’s face it, it’s always easier for us to demote King Jesus to Secretary of Afterlife Affairs, blend into the empire, salute the flag, conform to the crowd, and live like everyone else— but especially so in Peter’s day.

Nero sewed Christians in hides and set dogs on them.Given the bewildering degree of suffering and persecution his churches endured, it’s remarkable the rhetorical tone that Peter the Preacher strikes in this epistle. Peter the Preacher never attempts no anodyne Hallmark card comfort. Peter the Preacher seems shockingly indifferent about indulging the questions of theodicy his listeners were surely asking. Why have such sufferings been visited on us?

Nero wrapped Christians in wax and struck a match to them.And what does Peter the Preacher give them? Not platitudes about the victorious life. Not three tips to triumph in your hardships. Not even pastoral care.

No, Peter’s message to his suffering people— it’s almost all exhortation.Evidently, Peter thinks Easter makes us capable of much more than we give ourselves credit.Get your head on straight. Fix your mind on the Kingdom drawing near. Be sober. Live as children of obedience. Put away all malice and guile and envy and slander and insincerity. Husbands and wives, submit to one another as Christ. When you’re around unbelievers, don’t let behavior screw up your message. Pray for the president you loathe.

Be holy.

In every realm of your life, be holy because you have been begotten anew by Jesus Christ who is the living and abiding Word of God.You have been begotten anew.

The Gospel undergirds the exhortation.The promise precedes the commands.The logic is critical:

In Jesus Christ, God has begotten us anew.

Therefore, love your brothers and sisters.

Therefore, live lives that corroborate your confession.

Therefore, conform the community to the Lord’s commands.

Look people, I know you’re suffering, Peter means to say, but apart from the grace of God in Jesus Christ PERISHABLE is the last word stamped on every one of us. “All flesh is like grass,” Peter writes, quoting the prophet Isaiah, “all its glory like the flower of the grass. The grass withers, and the flower falls, but the Word of the Lord— that is, Jesus Christ— endures forever.” And you have been born anew into him.

We all come into this world with an expiration date. Keith Richards notwithstanding, none of us is getting out of life alive, Peter says. PERISHABLE is the last grim word for every one of us.

Nevertheless!

In Jesus Christ, we have received a word beyond that last word. With verse twenty-three, the Apostle Peter returns to a theme he already introduced in verse three, being begotten anew. And just so you don’t mistake this for another of Peter’s exhortations, just so you don’t mistakenly think getting born again is something you got to get up and do, Peter puts it in the passive participial form.

Having been begotten anew.It refers to a prior act of God upon you.You’ve probably seen the Romans Road Salvation Plan diagramed in the evangelical tracts. On the left, there’s usually a stick figure representing all of unbelieving humankind. Often beneath the stick figure it will say something like, “Our Problem,” and list Sin and Death along with the relevant verses. On the right side of the diagram, meanwhile, is typically a triangle for God, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. And between the two sides stands a steep, unsurpassable chasm. The more enthusiastic versions of this illustration put spitting tongues of hellfire at the bottom of the ditch.

The takeaway is simple, right?

A gulf separates humanity from God, a divide we could never hope to cross on our own. Fortunately, the cross of Christ spans the breach, bridging the distance from the human situation to God. If we wish to cross over, if we want to change our situation from sin and its fatal wages to fellowship and union with God, then we’ve got walk from one side to other by means of the cross. That is, we’ve got to repent and believe. We’ve got to have faith. We’ve got to be born again. Despite its staying power, there’s a number of problems with the image not the least of which is that this is not how Peter, or Paul for that matter, speak of our having been begotten anew.

The good news of the Gospel is impossibly better!Jesus Christ has done more than provide you the means to cross over to the other side. The glad tidings of the Gospel are that Jesus Christ has taken you into himself and carried you. No matter who is listening to this, right now— whomever you are, you’re already on the other side.

You’re home free.You’re safe in Jesus Christ.All of us, every last one of us, whether we know it or not, whether we believe it or perceive it or not, we are already on the other side.

We have all been conceived anew by the Word, begotten again by the work of the living and abiding Word.

As the apostle Paul puts it to the Corinthians, “One has died for all; therefore all have died.”

Think about that— “One has died for all; therefore all have died.” That’s a non sequitur.April 19, 2023

Whither the Body?

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

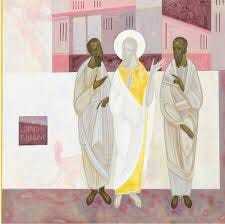

Luke tells us that on the third day after the unseemly events on Golgotha, the Risen Jesus encountered two disciples who were on their way home in Emmaus. Strangely, Cleopas and the other unnamed disciple do not recognize their traveling companion until “he took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him…”

Coincident with the instant of their recognition, Luke reports, the Risen Christ “vanished from their sight.”

Note the difference:

Luke does not say Jesus walked off into the distance.

Nor does Luke write that Jesus decided to lodge outside of Emmaus before making his next Easter appearance in Capernaum by sea.

No, it’s: “He vanished from their sight.”

An odd body indeed.

Both the scriptures and the creeds are clear. The appearances of the Risen Jesus, such as on the one recorded in Luke 24, are decisive for the Resurrection claim of the primal church. The status of Jesus’s garden tomb is not so decisive. The tomb could have been empty while Jesus nevertheless could have been dead. Karl Barth and others even go so far as to suggest that the tomb could have not been empty and Jesus nevertheless could be said to be risen.

The appearances of the crucified, dead, and buried Jesus to his disciples are the occasion for Easter faith not the occupancy status of his resting place. Thus, a question presents itself that is all-important even if it is often unexamined.

What happened to Jesus’s body?The Father raised the Son’s body to where exactly?Where is the Risen Jesus in between the appearances of him? For that matter, at Eastertide’s end when the Risen Jesus ascends to sit at the Father’s right hand in heaven whither does the Son go?The Gospels make it clear. Between his Easter appearances, the Risen body of Jesus had no location in this world.

The Risen Jesus did not rent a room at the Super 8 in Jerusalem.

He was not glamping in Galilee.

He was not couch-surfing in Samaria.

Again, “he vanished from their sight.” But also the Risen Jesus was precisely not a ghost. He had wounds that neither festered nor healed, yes, yet he eats breakfast with his friends. He’s tangible in that, in the case of Thomas, he can make himself our object.

Of course, it’s true that the Resurrection is an event that could not have been photographed. The stone that’s been rolled away from the tomb testifies to an event that’s already happened not to the event itself. The Resurrection is not an event that could have had witnesses because the Resurrection is an event that happens to time as much as it’s an event that happens in time. Still, what’s straightforwardly clear from scripture is that the Resurrection was a bodily resurrection of the crucified Jesus.

To make it plain—

A body requires a place.

This locateability is exactly what distinguishes a body from a spirit.

Where is the place to which the Risen body of Jesus was raised?

Where is the place the Risen body of Jesus now resides?

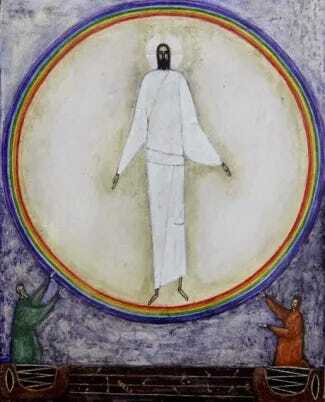

Heaven is the place so named in the scriptures and the creeds. This is an answer that came somewhat easier to believers who belonged to previous centuries.In the Bible, “heaven” is simply the place God makes for himself within his creation. Earlier Ptolemaic cosmology posited just such a place for us to envision; indeed, we persist in so conceiving it. Heaven, in Ptolemy’s understanding of the cosmos, is the location in creation beyond the skies and the stars.

Above the clouds. Up there. In the great bye and bye.

We still say.

Even though we know it’s not true.

Copernicus undid this accommodation to the faith’s dogma. No longer can we operate as though heaven is a place in the cosmos. Despite the plot of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, we cannot venture our way to the body of the Risen Jesus by means of space travel. There is no “Man Upstairs.”

This is not actually a problem. Even Thomas Aquinas understood that the faith itself requires us to say what Copernicus later compelled us to accede. “Plainly,” Aquinas argues in the Summa, “the body of Christ does not come to be in the sacrament by spatial motion.”

April 18, 2023

Hitmen and Midwives

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I’ve started a new series talking about preaching with preachers and those who suffer preachers. My friend Dr. Ken Jones kicked off the project by discussing what we’re calling the 9.5 Theses on Preaching. More of those to come.

In this installment, I talked to the rector of St. David of Wales, Paul Nesta about the the role of wonder and storytelling in the sermon.

You can find the previous conversation HERE.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 17, 2023

Join me on Notes

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Hey Folks,

Check out Substack Notes.

It’s like Twitter but without the Troll-in-Chief and Nazis.

Notes is a new space on Substack for readers and writers to share links, short posts, quotes, photos, and more. I plan to use it for things that don’t fit in the newsletter, like work-in-progress or quick questions.

How to joinHead to substack.com/notes or find the “Notes” tab in the Substack app. As a subscriber to Jason Micheli , you’ll automatically see my notes. Feel free to like, reply, or share them around!

You can also share notes of your own. I hope this becomes a space where every reader of Jason Micheli can share thoughts, ideas, and interesting quotes from the things we're reading on Substack and beyond.

If you encounter any issues, you can always refer to the Notes FAQ for assistance. Looking forward to seeing you there!

It's All Christophany

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Luke 24.13-35

The lectionary Gospel for the Third Sunday of Eastertide is Luke’s account of the Risen Christ encountering two disciples on the road to Emmaus. Notice, Cleopas and the other disciple on the road to Emmaus, they’re not unawares.

They’ve heard the Easter news. They’ve heard from the women who dropped their embalming fluid and fled to tell it. They’ve heard from Peter. They’ve heard that the tomb is empty.

And yet—

Having heard that Death has been defeated, having heard that the Power of Sin has been conquered, and having heard that self-giving, cheek-turning, cruciform love has been vindicated from the grave…

Our moral imagination is so impoverished that the first Easter Sunday isn’t even over and here we are (in these two disciples) walking back home as if the world is the same as it ever was and we can get back to our lives as knew them.

They’ve heard the Easter news, yet these two disciples still make two common mistakes— two common reductions— in how they understand Jesus. “Jesus of Nazareth was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God,” they tell the stranger (who is Christ). True enough, but not sufficient. “We had hoped he would be the one to liberate Israel,” they tell him, “we had hoped he was the revolutionary who would finally free us from our oppressors.” Again, their answers aren’t wrong; their answers just aren’t big enough.”

It’s not until this stranger breaks bread before them that their eyes are opened and they run— in the dark of night, eight miles to Emmaus, they run— to go and tell the disciples what they’ve learned. And when they get there, after the Risen Jesus has taught them the Bible study to end all Bible studies— what have the learned?

They don’t call Jesus a prophet. They don’t dash after the disciples to report “God has raised Jesus, the prophet, from the dead.” They don’t call Jesus a liberator. They don’t run to Peter and say “Jesus the revolutionary has been resurrected.” They don’t even call him a savior or a substitute. They don’t dash after the disciples to report, “The Lamb of God who took away the sins of the world has come back.”

No, after the Risen Jesus interprets Moses and the prophets for them (ie, the Old Testament, the only Bible they knew) they take off to herald the return of Jesus the kurios.

They confess their faith in Jesus as kurios.“The kurios is risen indeed!” they proclaim to Peter. Luke book-ends his Gospel with that inconveniently all-encompassing word kurios.

The whole entire Bible, Jesus has apparently taught these two, testifies to how this crucified Jewish carpenter from Nazareth is the kurios who demands our faith.Kurios.

Lord.

The word we translate into English as faith is the word pistis in the Greek of the New Testament. And pistis has a range of meanings. Pistis can mean confidence or trust. It can mean conviction, belief, or assurance. And those are the connotations we normally associate with the English word faith.

In Christ alone by grace through trust alone.

Through belief alone, is how we hear it.

But— here’s the rub— pistis also means fidelity, commitment, faithfulness, obedience.

Or, allegiance.

Allegiance.

Now, keep in mind that the very first Christian creed was “Jesus is kurios” and you tell me which is the likeliest definition for pistis.So how did we go from faith-as-obedience to faith-as-belief?How did get from faith-as-allegiance to faith-as-trust?

When Luke wrote his Gospel and when Paul wrote his epistles, Christianity was an odd and tiny community amidst an empire antithetical to it. Christianity represented an alternative fealty to country and culture and even family.

Back then, baptism was not a cute christening. Baptism was not a sentimental dedication. Baptism was not a blessing, a way to baptize the life you would’ve lived anyway. Back then, to be baptized as a Christian was a radical coming out. It was an act of repentance in the most original meaning of that word: it was a reorientation and a rethinking of everything that had come before.

To profess that “Jesus is Lord” was to protest that “Caesar is not Lord.”The affirmation of one requires the renunciation of the other.Which is why, in Luke’s day and for centuries after, when you submitted to baptism, you’d first be led outside. By a pool of water, you’d be stripped naked. Every bit of you laid bare, even the naughty bits. And first you’d face West, the direction where the darkness begins, and you would renounce the powers of this world, the ways of this world, the evils and injustices of this world. And the first Christians weren’t bullshitting. For example, if you were a gladiator, baptism meant that you renounced your career and got yourself a new one. Then, having left the old world behind, you would turn and face East, the direction whence Light comes, and you would affirm your faith in Jesus the kurios and everything your new way of life as a disciple would demand.

And the first Christians— they walked the Jesus talk of their baptismal pledge. For example, Christians quickly became known— before almost anything else— in the Roman Empire for rescuing the unwanted, infirm babies that pagans would abandon to die in the fields. Baptism wasn’t an outward and visible sign of your inward and invisible trust. Quite the opposite.

Baptism was your public pledge of allegiance to the Caesar named Yeshua.If that doesn’t sound much like baptism to you, there’s a reason. A few hundred years after Luke wrote his Gospel and Paul wrote his letters, the kurios of that day, Constantine, discovered that it would behoove his hold on power to become a Christian and make the Roman Empire Christian too. Whereas prior to Constantine it took significant conviction to become a Christian, after Constantine it took considerable courage NOT to become a Christian. After Constantine, now that the empire was allegedly Christian, the ways of the world ostensibly got baptized; consequently, what it meant to be a Christian changed. Constantine is the reason why whenever you hear Jesus say “render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and render unto God the things that are God’s” it doesn’t occur to you that Jesus is being sarcastic. What had been an alternative way in the world became, with Constantine, a religion that awaited the world to come.

Jesus was demoted from the kurios, who is seated at the right hand of the Father and to whom has been given all authority over the Earth, and Jesus was given instead the position of Secretary of Afterlife Affairs.

April 16, 2023

Easter Hope is Not Inert

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

1 Peter 1:3-9

Friedrich Nietzsche said the fatal problem with Christianity is that there has only been one real Christian in human history and that He had died on the cross.

David Bentley Hart writes that when he finished translating the New Testament the work left him with a deep sense of melancholy along with the suspicion that most of us who go by the name “Christian” ought to give up the pretense of wanting to be Christian.

Notice the distinction. He didn’t say we should give up the pretense of being Christian. He said we should give up the pretense of wanting to be Christian.

He asks:

“Would we ever truly desire to be the kinds of people that the New Testament describes as fitting the pattern of life in Christ?”And before you answer, consider the new way of life Christ gave his community to live.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with offenders.

By loving them.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with violence.

By suffering.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with sinners.

By eating with them.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with money.

By sharing it.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with debt.

By forgiving it.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with enemies.

By dying for them.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with a corrupt society.

By embodying the New Age not smashing the Old.

This is why, as St. Luke reports without embarrassment or hedging, after Easter, the price to become a Christian was that you sell all your property and possessions, distribute the proceeds to the poor, and then rely on the mutual support of the community for your needs. Barnabas, for example, on becoming a Christian, cashed in his 401K and handed over all the money to the body of Christ.

Just imagine, the character a community would need to exemplify in order for a stranger to trust it with all of their needs.

For the earliest generations of Christians, the Church was an alternative community with no Second Generation members, for it grew not through the family but by witness and conversion. Christians were the alternative Christ had made possible in the world through his death and resurrection.

Thus, Hart notes, the first Christians were:

“A company of extremists, radical in their rejection of the values and priorities of society not only at its most degenerate, but often at its most reasonable and decent.

They were rabble, a disorderly crowd.

They lightly cast off all their prior loyalties and attachments: religion, empire, nation, tribe, family and safety.”

They did so, Hart argues, because one thing that is in remarkably short supply in the New Testament is common sense. The Gospels, the Epistles, the Book of Acts, Revelation—all of them are “relentless torrents of exorbitance and extremism” in which “there are no comfortable medians, no areas of shade, for everything is cast in the harsh and clarifying light of Christ’s returning reign.”

Everything is cast in the harsh and clarifying light of Christ’s return.In other words, the communities of the New Testament exemplify life lived according to the future, life lived as citizens of a Kingdom not yet here but near.

To be the kinds of people the New Testament affirms, David Hart concludes in his preface to the New Testament, we would have to become strangers and exiles— sojourners on the earth.

According to the Second Sunday of Eastertide, this is exactly who God has already made us in Jesus Christ:

April 14, 2023

Believing is Seeing

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

My favorite verse of scripture?

Romans 8.1 “There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” is my favorite verse of scripture.”

The most challenging verse for me is Matthew 5.48, Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount, “Be perfect therefore as your Father in Heaven is perfect.”

The funniest verse to me is 2 Kings 2.23 where some boys jeer at the prophet Elisha “Get out of here, baldy!” So Elisha calls down a curse on them in the name of the Lord. Then two she-bears came out of the woods and mauled forty-two of the boys.

But I’d have to say the Bible verse that most irritates me is the one assigned for the Second Sunday of Easter:

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples which are not written in this book” (John 20.30).John apparently left stuff out. Should the church follow the reading of the lectionary passage this Sunday with an amended response, “This is most of the Word of God for the People of God. Thanks be to God?”

John believes he’s relaying to you the most important news that’s ever been told— in the Greek you can even sense the breathless way he’s recounting his Gospel.

Why then would John leave anything out?If the whole point of the Gospels is to prove to us that the world responded to God’s love made flesh by crucifying him but that God vindicated him by raising him from the dead, then why would John not include every detail? Perhaps more than any other time on the liturgical calendar, the season of resurrection is an occasion when even the every Sunday sort of Christians think they need to hide their doubts. And usually we hide our doubts by acting as though others shouldn’t have any doubts of their own.

As Stanley Hauerwas puts it,

“We try to assure ourselves that we really believe what we say we believe by convincing those who do not believe what we believe that they really believe what we believe once what we believe is properly explained.”

Easter, the Gospels make clear, is an occasion for doubt as much as it is an occasion for faith.

Both Luke and John are clear and unembarrassed in their reporting. Witnessing an appearance of the Risen Jesus firsthand did not allay the doubts of some of the disciples.

With his own two eyes, Thomas saw Jesus feed 5,000 with just a few loaves and a couple of fish. When Jesus raised Lazarus, called him out of his tomb, stinking and 3 days dead, Thomas was there. And Thomas was there to hear for himself when Jesus told Martha, the grief-stricken sister of Lazarus, “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, yet shall they live. And everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die.”

But all the first-hand evidence, all the eyewitness proof, all the personal experience wasn’t enough to convince Thomas.

Because on Easter night, after the women in Mark’s Gospel have run away from the tomb terrified and not breathing a word to anyone, the disciples hide. They hide behind locked doors and the Risen Christ comes and stands among them— just as he’d predicted he would- and says “Peace be with you.”

But Thomas wasn’t there.

The Gospel doesn’t give even an inkling of where Thomas was. It just says, “Thomas was not there with them when Jesus came.”

“Seeing is believing” we say, but three years of seeing for himself, of hearing for himself, of being right there with him— it wasn’t enough to convince Thomas that Jesus really was who he claimed he was. Afterwards when the disciples tell Thomas what had happened, Thomas doesn’t respond by saying:

All ten of you saw him? Alright, that’s good enough for me.

No.

Thomas says, “Unless.”

I will not believe unless.

Unless I see his hands and his feet. Unless I can grab hold of him and touch his wounds. Unless I can see for myself what Rome did to him. I need proof. I need facts. I need evidence before I will believe.

The first Easter wasn’t just a day.

The Risen Jesus hung around for 50 days, teaching and appearing to over 500 people.

7 days after the first Easter Day, Jesus appears again in that same locked room as before and Jesus says “Peace be with you.” And this time, this time Thomas is there.

Jesus offers Thomas his body: ‘Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe.’

And Thomas reaches out and Thomas touches Jesus, grabs at the wounds of Jesus, to see the proof for himself...

Actually no.

He doesn’t.

That’s the thing—

We assume that Thomas touches Jesus’ wounds. Artists have always depicted Thomas reaching out and touching the evidence with his own hands. Duccio drew it that way. Caravaggio illustrated it that way. Peter Paul Rubens painted it that way.

Artists have always shown Thomas sticking his fingers in the proof he requires in order to believe.And that’s how we paint it in our own imaginations.Yet, read it again, it’s not there.The Gospel gives us no indication that Thomas actually touches the wounds in Jesus’s hands. John never says that Thomas peeked into Jesus’ side.

The Bible never says Thomas actually touches him.That’s got to be important, right? The one thing Thomas says he needs in order to believe is the one thing John doesn’t bother to mention.

Instead John tells us that Jesus offers himself to Thomas and then the next thing we are told is that Thomas confesses: ‘My Lord and my God!”

The one thing Thomas says he needs before he can believe is the one thing John doesn’t bother to give us.Perhaps this is John’s way of telling us that Thomas doesn’t need the proof he thinks belief requires.He doesn’t need to hold the hard, tangible evidence for himself. He doesn’t need exhibits A and B of Jesus’ hands and side. He doesn’t need to have all his lingering doubts and questions resolved in order to have faith. The one thing Thomas says he needs before he can believe is the one thing John doesn’t mention.

Thomas, even if he doesn’t realize it, has already been given everything he needs in order to believe.

This why John does not bother mentioning “the many other signs” Jesus did in the presence of his disciples. John doesn’t tell us more because he’s given us all we need. He’s given us everything we need to take a chance, to say “My Lord and my God” and then to have life in his name.

John doesn’t tell us more because the Gospel is not meant to be information about which we make up our minds.The Gospel is an invitation to have life not to have an opinion.To have life in his name is to live as though your name is Jesus.

We think we need proof.

But being a Christian is not about being convinced beyond a shadow of a doubt.It’s not being able to prove that Jesus fed 5,000 hungry people. It’s not about being able to explain how God created, how Jesus undid Death or why our world isn’t what God wants for it. If being a Christian is about knowledge or facts or certainty then, by all means, John should give us every detail he’s got. If the point of Christianity is eliminating our every doubt then John should leave nothing out.

But if it’s about living life in his name, living as though he is risen indeed, then John’s told us everything we need. To live.

If it’s about proving the resurrection, then John hasn’t provided nearly enough to convince me.

But if it’s about living the resurrection, then John’s already told us everything we need.

To follow the Risen Christ is not to be certain. It’s not to understand or to know. It’s not to have had something proven to you to the point where you can prove it to others.

To follow the Risen Christ is to take a chance, to take a risk, to trust that whatever we mean by ‘Lord and God’ is found in Jesus. To follow Christ is to risk that trust and then to have life in his name- to live in such a way that makes absolutely no sense- no sense- if God has not raised Jesus from the dead.

“Seeing is believing” we say.Except when it comes to Jesus, it works the other way round. Believing is seeing. Believing gives you a whole new way of seeing.Believing is seeing.

Seeing the world the way God sees it: as broken and sinful and corrupt yet precious and loved and worth redeeming.

Believing is seeing.

Seeing you as God sees you: as beautiful and beloved and worth dying for and worthy of a more interesting life than our culture even asks of you.

Believing is seeing.

Seeing forgiveness and mercy and grace and loving your enemies and turning the other cheek and blessing those who curse you as the building blocks for a New Creation.

Believing is seeing.

Seeing the future Kingdom Jesus taught about as something that can be lived and made present in the here and now.

Believing is seeing.

Seeing God, the infinite, eternal, all-powerful God, in the face of the poor and the weak. Seeing that whenever you do something for one of them, the least among us, you’ve done it to God himself.

Believing is seeing.

Seeing the sin you committed and knowing that it’s forgiven. Seeing the broken relationship in your life and knowing it can be repaired. Seeing the despair and forsakenness you feel and knowing you’re not alone. Seeing the hurt and abuse you’ve suffered and knowing it can be healed. Seeing Death, staring it straight in the face, and knowing that Love wins.

Believing is seeing.

Seeing that the proof of Resurrection isn’t in touching the wounds in Jesus’ hands and feet but in living in a manner that makes no sense— NO SENSE— if God has not raised Jesus from the dead.

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

April 13, 2023

Risen with Nary a Word of Condemnation

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Mark and Matthew, Luke and John— the Gospels all agree the very first reaction to news of the resurrection is fear.

The soldiers guarding the tomb faint from fear.

The women, come to anoint the body, run away. Terrified.

The disciples lock the doors and cower in the corner.

The first response to the news “Christ is Risen” is not “He is Risen indeed!” It’s panic. Fear. Terror. Even Mary Magdalene appears deeply unsettled if not scared. Why are they so frightened?

Are they afraid that what Caesar did Jesus might still be done to them? Or do they fear the news that this particular Jesus has come back? This Jesus who harassed them for three years, who called them to abandon their family businesses, and who complicated their lives with talk of cross-bearing. Are they afraid that they’re not finally rid of this Jesus after all?

Is Jesus what’s so scary about the news, “Jesus has been resurrected!”?

Or, is it the word “resurrection” itself that makes them white-knuckled afraid?

Was the Easter word enough to provoke not just awe but frightened shock?

Remember, for Jesus and the apostles the Old Testament was simply the Bible; the Tanakh were the only scriptures they knew.

The primary passage in the Hebrew Bible which anticipates a general resurrection is Daniel 12. This is not necessarily a text to which the immediate, reflexive response would be “Alleluia!”Not only was Daniel the last book added to the Hebrew Bible, it was the most popular scripture during the disciples’s day. Prior to the exilic experience, Israel had no substantive concept of heaven. When you died, you were dead. That was it, the Jews believed. You worshipped and obeyed God not for hope of heaven but because God, in and of himself, is worthy of our thanks and praise. Only, when Israel’s life turned dark and grim, when their Temple was razed and set ablaze, when their promised land was divided and conquered, and when they were carted off as exiles to a foreign land, the Jews began to long for a Day of God’s justice and judgement.

If not in this life, then in a life to come.

And so the resurrection the prophet Daniel sees is a double resurrection.Those who have remained righteous and faithful in the face of suffering will be raised up by God into God’s own life everlasting. Just so, those who’ve committed suffering, they might be on top now in this life but one day God will raise them up too, not to everlasting life but to everlasting shame and punishment.

In the only Bible the disciples knew, then, the word resurrection was a hairy double-edged sword, even scarier than the bunny in Donnie Darko.April 12, 2023

Q: Is Doubt Credible?

Jason Micheli is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Hi Friends,

Thank you for welcoming me into your inbox and your headspace.

In addition to the public posts, I’ve got a few projects in the works for folks who take the plunge and subscribe to the site (ie, my mom).

One project is this catechism which I started years ago but did not complete because of a vacation called cancer. I’m reworking it and aim to round it out as I go. If you missed it, here’s the Kick-Off Catechism Post.

Another project is the fruit of some talks I delivered this fall on grace and proclamation for the Anglican Church of Canada. A number of people responded that those lectures were helpful so I’ve started a series called “Hitmen and Midwives: Talking Preaching with Preachers.” I’ve kicked it off with a series of conversations (The 9.5 Theses on Preaching) with my friend Dr. Ken Jones and I plan to include other preachers and pew-sitters down the road.

If you’ve got suggestions for other material you’d like to see in this space, please let me. Shoot me an email or leave a comment.

9. Is disbelief in God credible?Yes.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers