Jason Micheli's Blog, page 75

May 23, 2023

Why Does the Holy Spirit Descend on Shavuot?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Sunday is Pentecost, and as always we read from St. Luke’s sequel, the Book of Acts, where the disciples are back in the Upper Room where they’d been the night they betrayed him.

“And suddenly,” St. Luke says, there’s a sound— not like a still, small voice but a mighty rushing wind. And the Holy Spirit descends like fire, and people start speaking, and even though they’re speaking different languages there’s simultaneous translation.

All these different languages but everybody understands everybody. The Holy Spirit descends. And everybody starts speaking and everybody understands everybody.

The commotion gathers a crowd in the street, and the crowd starts to gripe: Those Christians are doing the same thing they did when Jesus was with them— they’ve been drinking (which, if you’re counting at home, is the first and last time anyone ever accused Christians of being fun).

Peter comes out to the crowd. And Peter speaks.

Remember where we left Peter in the story?

Back on the night they’d been in that same Upper Room:

“Jesus? Jesus who?”

The third time he actually curses Jesus’s name, which sounds worse when you translate the name the angel gave him:

“Jesus? Curse this Jesus whoever he is. Curse this savior.”

And then the cock crowed.

But on Pentecost they’re back in the Upper Room, and the Holy Spirit descends and Peter speaks. Peter says to the crowd:

“We’re not drunk— yet. We’ve still got an hour before brunch. No, no, no. All this your hearing, this is what the prophet foretold.”

And then Peter preaches this long sermon that crescendos with Peter proclaiming:

Let’s just get right down to it: Why does the Holy Spirit come at Pentecost?“This Jesus, whom you crucified, God has him raised from the dead [for our justification] and God has made him Lord. Be baptized.”

Make sure you’ve got my question straight. I’m not asking “Why does the Holy Spirit come?”

The Holy Spirit has already come.Pentecost is not the arrival of a heretofore absent Spirit.The Holy Spirit descended upon Jesus when he first preached. The Holy Spirit overshadowed his mother’s womb. Even before the incarnation, the Holy Spirit spoke to us by the prophets and, says Job, the Holy Spirit likewise enabled the understanding of those prophetic utterances.

But why does this instance of the Spirit’s occurrence, with fire and wind, come at Pentecost?

Or, as the Jews call it in Hebrew, Shavuot.

The Festival of Weeks.

Five weeks (penta-) after the Passover.

If Jesus sends the Holy Spirit to be with us in this in-between time between Christ’s first coming and his coming again, then why does the Holy Spirit not descend upon the disciples as they’re building make-shift tents of sticks and leaves to celebrate Sukkot, the Jewish festival that commemorated Israel’s wandering in the wilderness in between their rescue from captivity and their deliverance into a promised kingdom of God.

Why Shavuot? Why not Sukkot?For that matter, Yom Kippur would make sense too.

May 22, 2023

I Need to Drive Your Toilet

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Genesis 11.1-9 and Acts 2.1-18

I studied five years of Latin in high school and four years of German. I can still decline the word for ‘farmer:’ acricola, agricolae, agricolam. And I can recall enough German to appreciate Indiana Jones on a deeper level. I studied Greek and Hebrew in seminary, and I still know them well enough to venture into the Old and New Testaments like a treasure hunter armed with a few well-chosen tools. But when it comes to speaking, when it comes to listening, I’ve never been very good at languages.

I’ve always heard how languages come easier for babies than they do for adults— their minds are like sponges, so goes the cliche. But, really, I think the difference is that no one hands out little treats when an adult finally gets the right word for “potty” or “hungry.”

Despite my relative ambivalence about languages, on my second day of my first semester of college I decided to enroll in French class. My roommate and I were sitting in a boring Intro to English Literature course, listening to a beer-bellied, gray-haired professor recite Beowulf in Old English. And across the hall, in the classroom opposite ours, we both noticed a twenty-something, red-haired woman standing in front of a chalk board wearing a tight leather skirt, teaching French.

We changed our schedules that afternoon.

The French teacher’s name was Isabelle, but, because of the siren-like spell she cast over my friend and I, to this day my wife refers to her as Jezebel. My interest in French more or less began and ended with Isabelle but, once I’d enrolled, the college required me to stick it out for three additional semesters. The good thing about French is that you can get by by approximating an accented mumble. My own accent slash mumble was a hybrid of Charles Aznavour and Detective Briscoe from Casablanca.

I passed the written exams by rote memorization, and I survived the listening comprehension tests by correctly assuming that most French conversations were about Miles Davis or American Imperialism. After four semesters, I ended up with an A average but the memory of Isabelle lingered longer. Today I can recall a few French words, but when it comes to understanding, it’s all confusion for me.

“And the Lord said, “Look, the people all have one language; this is only the beginning of what they will do.””

Years ago, I traveled to France to spend a week at Taize, an ecumenical monastery in the Burgundy countryside. Taize is a destination for thousands of Christian pilgrims from places scattered all over the globe. And “pilgrimage” seems an appropriate descriptor when you consider how long and trying and confusing the journey there can prove.

At the beginning of the pilgrimage I was wandering around CDG airport in Paris, trying to locate my connecting flight. The gate number printed on my boarding pass didn’t match the listings on the terminal television screen. I made the mistake of walking up to the desk at what should’ve been my gate and asking for help.

“I’m just wondering if I’m at the right gate,” I said.

The frenchman behind the counter stared at me blankly and said ‘Oui.’

Not satisfied he’d understood me, I handed him my boarding pass and decided to speak every traveling American’s second language. I just spoke louder, “I’M JUST WONDERING IF I’M AT THE RIGHT GATE.”

May 21, 2023

Everything is Going to be Okay

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Ascension Sunday: Luke 24.50-53

I was a teenager.

I was a reluctant churchgoer, cynical towards the world generally and sneering towards the faith especially. I was about six months into my mother’s mandated worship attendance when I came forward, like so many other ordinary Sundays, down the aisle, hands held out like the beggar I refused to believe I was, when suddenly, for a moment, like a rip of lightening, the hands tearing off pieces from the loaf were no longer the hands of the man I knew to be named Steve Chiocca. Nor was the body to which those hands belonged his body.

I cannot say how I knew.

I simply knew.

I knew it was Jesus.

“This is my body, broken for you,” he said— out loud? In my head?

There were holes in the hands that placed the bread in mine. It scared the shit out of me. And it made me a believer. It’s probably the only thing that could’ve made a person like me into a believer.

I don’t often speak of it because scripture warns us against becoming spiritual experience seekers. But I know that Jesus is risen not because the scriptures and the apostolic testimony so attest; I know that Jesus is not dead because I’ve met him. If he is risen then perhaps, as Luke reports, he ascended indeed.

Yet—

How are we to speak intelligibly of such an event, knowing, as we do, that heaven is not “up there?”I remember—

I dipped the piece of bread into the chalice and glanced furtively to the left of the woman bearing the cup. I saw that the server was once again Steve, and I felt relieved.

I know not how Jesus departed, but I do know that he did not go up, up, up, and away.In some ways, Christ’s ascension is an item of dogma on the slimmest of basis. Only Luke mentions it and he does so twice. Read in isolation, Luke’s account of the ascension could create the impression that Jesus has spent the last forty days since his resurrection on terra firma but this is straightforwardly not the case. Luke tells us that on the third day after his crucifixion, the Risen Jesus encountered two disciples who were on their way home in Emmaus. Strangely, Cleopas and the other unnamed disciple do not recognize their traveling companion until “he took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him…” Coincident with the instant of their recognition, Luke reports, the Risen Christ “vanished from their sight.”

Luke does not say, “Jesus walked off into the distance.”No, it’s, “He vanished from their sight.”An odd body indeed.

Later that night, the disciples are hiding behind locked doors when at once the risen Jesus is standing among them. Jesus does not knock on the door. Jesus does not step through the door. Jesus is simply and suddenly standing amongst them.

Whence did he come?If the risen Jesus ascends forty days after Easter, then where was he in between his appearances and how does that influence our understanding of the ascension?

The Gospels make it clear. Between his Easter appearances, the Risen body of Jesus had no location in this world. The Risen Jesus did not rent a room at the Super 8 in Jerusalem. He was not glamping in Galilee. He did not couch-surf in Samaria.

He appeared. And then he vanished from their sight.

Whatever else the ascension means, therefore, it does not signal a change in Jesus’s spatial location.The risen Jesus was not exclusively located on earth during the forty days after his resurrection just as the ascended Jesus is assuredly not now located “up there.”

Where was the risen Jesus in between his Easter appearances? Where is he now if the ascension does not narrate his journey from one place in the cosmos to another place in the cosmos?Diane was a member of my first congregation in New Jersey. The first funeral I ever preached was for Diane’s father, who came home from work one afternoon, went down to the basement, and committed suicide. Before the police were able to reach Diane and break the news to her, Jesus came to her.

“He was standing in the kitchen, on the linoleum floor, in front of the microwave and toaster oven. I don’t know how I knew it was him, because he didn’t say anything, but I knew he wanted to comfort me for some reason. Jesus wanted to comfort me, and here I was embarrassed by all the dirty dishes in the sink.”

“How did he leave?” I asked her.

“How did he leave?” She stammered, “I don’t know. He just, you know, suddenly wasn’t there anymore.”

Ever since Copernicus’s heliocentric revolution, we cannot seriously entertain the picture of heaven as above us or, even, out there in the beyonds of space.Just as we know the earth is not the center our solar system, we know heaven is not above the clouds. The medieval art that depicts the ascension is not meant to make us laugh but it does nevertheless. After all, we cannot envision the topography of the cosmos as they did in the ancient Mediterranean world.

Though, it’s not even clear from scripture how literally they took that topography.

Notice—

The disciples respond to Jesus’s ascent into heaven to sit at the right hand of the Father by going to the temple (“continually”) to bless God.

Why do they go to the temple?

Because they are Jews and the God of Israel who was in heaven at Jesus’s left hand was likewise seated on the cherubim throne in the temple.

It was just so at Mt. Sinai in the Book of Deuteronomy.

The Lord who was in heaven was also above Moses on the mountaintop but also on the earth as great fire yet also still in the fire whence his voice came.

Centuries before Copernicus, scripture nonetheless had a more nuanced understanding of heaven’s address.

Despite the plot of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, we cannot venture our way to the body of the Risen Jesus by means of air travel.

There is no “Man Upstairs.”

If we really believed that Jesus ascended to another location above and beyond us, then fundamentalists would be launching rockets into space instead of banning books from schools.

So—

If heaven is not “up there” then where?

Whither the risen Jesus?

Nesteron, lived in Iran and belonged to an observant Muslim family, yet one day the risen Jesus appeared to her.

“What was it like?” my friend asked her.

“It wasn’t like an audible voice, but it wasn’t like a voice in my head either. It was something altogether different but altogether real.”

Unbeknownst to Nesteron, at this same time, her sister, who was

studying in Europe, had received the gospel from a classmate and been baptized.

Jesus later appeared to her and told her that she needed to go back home and share his gospel with Nesteron and their family.

When Nesteron’s sister arrived back at their family’s home in Iran, Nesteron greeted her by saying, “I know—you’re here to tell me about Jesus. I believe in him. I’ve met him.”

If not “up there” then where?

And given that wherever how is he also here?

Actually, the ascension is not about a where.

It’s about a when.

The ascension is not about space.

The ascension is about time.

To be sure, Luke uses spatial imagery to proclaim Jesus’s whither because the truth is almost impossible to conceive.

Where Luke gives us a picture, the rest of scripture instead relies on the concept of time.

So then, the risen Christ in the Book of Revelation attests that he is the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End, the First and the Last.

Jesus talks about himself in terms of time.

Likewise, the risen Christ, the apostle Paul writes, is the first fruit of what?

The new creation.

That is, the risen Jesus is the first moment of God’s promised future.

The question isn’t, “Where is Jesus?”

The question is, “When is Jesus?”

The Father raised Jesus from the dead and immediately translated him to the first moment after the End of this old aeon.

The ascension therefore is simply the demonstration of what was true forty days earlier.

The mystery is that God raised Jesus into the future.

The good news is that this future is also by grace our future.

His Easter appearances, therefore, are exactly what the Gospels would have us conclude— ghostlike yet not ghostlike, embodied yet different than before.

They are so because the risen Jesus comes from the future.

Thus, the question about the risen Jesus’s body is not a question of place but of time.

Resurrection translates Jesus from one point in space-time to another point without interfering with the Triune life.

Much like folding a piece of paper in half and piercing it with a pencil, leaving two holes that permit you to pass directly from one end to the other, Christ’s body can “pass” from one location in spacetime to another without interval or interruption.

Hector was an inmate at the prison where I served as chaplain. Hector came to see me one hot summer day, his olive skin blanched white from fright.

“Man, no joke, Jesus Christ was just there—in my cell—last night before lights out. He told me everything I done is all forgiven. And then he told me my kids are going to be alright. Preacher, don’t you get it? Everyone up in here is trying to get out and Jesus Christ broke in to tell me I’m forgiven.”

Hector looked terrified, but it didn’t stop him from asking me to baptize him on Sunday.

I didn’t ask him, but I think he would’ve mentioned it had Jesus left him by lifting off, up into the sky.

Of course, Luke depicts Christ’s ascension spatially. Two thousand years later, it’s still impossible for us to visualize what it means that the Father raised the Son in to the first moment of the last future. Fix instead on the good news.

Not only does Jesus live.Jesus lives in the last future.Therefore, the promises Jesus speaks to us in the present from that future are unconditional. They can’t be undone, not even by your sin— exactly because he lives with death behind him.

Not one of us can speak unconditional promises to another person. Every one of our promises are rendered conditional by the future of death. We cannot commit a future we do not control. Not so Jesus. Jesus’s promises to you are like wedding vows that do not end, as our vows do, with, “Until we are parted by death.”

The table, the font, the word— they are time machines.So when the ascended Jesus speaks from the final future into the present through wine and bread and says, “For you…for the forgiveness of all your sins…” you can take it to the bank.

Because he lives with death behind him.

When the ascended Jesus speaks from the last tomorrow into today through water and says to a baby, “You are mine. I will never let you go,” well, that child can live her life like she’s playing with house money.

Because he lives with death behind him.

And when the ascended Jesus speaks from then into now, through the lips of a preacher, “No matter what is going on in your life, your marriage, your family, the world or the church…chaos, confusion, heartbreak… everything is going to be okay…;”when the Jesus then says to you through me now, “Everything is going to be okay,” you can trust that that future is your future.

You can trust that future because he already lives there.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 20, 2023

Jesus-Flavored Ideologies

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

May 19, 2023

Curated Catechesis

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is a conversation I recently enjoyed with Sarah Hinklicky Wilson.

Check out her recent talk at the Mockingbird Conference.

Sarah is the Founder of Thornbush Press, launched in 2020, and author of a number of books under its imprint: I Am a Brave Bridge, Sermon on the Mount: A Poetic Paraphrase, Small Catechism: Memorizing Edition, Pearly Gates: Parables from the Final Threshold, To Baptize or Not to Baptize: A Practical Guide for Clergy, and A-Tumblin’ Down.

Since August 2018 she has lived in Mitaka, Japan, on the campus of Japan Lutheran College and Theological Seminary, where her husband Andrew L. Wilson is Professor of Church History. She serves as one of the pastors at Tokyo Lutheran Church near the Shin-Ōkubo station in central Tokyo. She is also an Affiliated Faculty Member at the Johannelund School of Theology in Uppsala, Sweden.

From July 2016 to July 2018 she lived in St. Paul, Minnesota, getting reacquainted with her home territory in between international sojourns. During that period she wrote a memoir about the year she spent in the newborn Republic of Slovakia when she was 17.

From 2008 to 2016 she lived in Strasbourg, France, where she worked at the Institute for Ecumenical Research, a close affiliate of the Lutheran World Federation, specializing in Eastern Orthodoxy and Pentecostalism. She continuse to serve as a Visiting Professor of the Institute and, as such, the Consultant to the International Lutheran-Pentecostal Dialogue. With her colleague Theodor Dieter from the Institute, she teaches an annual course in Wittenberg, Germany, on Martin Luther’s theology.

In 2010, Andrew and she followed the footsteps of Martin Luther’s pilgrimage from Germany to Rome five hundred (or maybe four hundred ninety-nine) years earlier.

She earned a Ph.D. in Systematic Theology in 2008 and an M.Div. in 2003 at Princeton Theological Seminary. During that time, Andrew and Sarah got married and became parents to Zeke. She served as pastor at a Slovak-American church in Trenton, New Jersey, and became the editor of Lutheran Forum, an independent theological quarterly, which she continued to do until the end of 2018. All her articles from that period are available here.

Before graduate school she spent one year working at First Things, where she first started publishing theological essays. Since her first in October 1998, she has published hundreds of articles in popular venues like Christianity Today, The Christian Century, and Books & Culture, as well as scholarly journals like Pro Ecclesia, Pneuma, Lutheran Quarterly, and Concordia Journal. She has edited four books and contributed to a few more.

She did her growing up in New York and New Jersey and still thinks of herself as a New Yorker, even though she hasn’t lived there since the last millennium.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 18, 2023

Q: How Should We Speak about God?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

13. How Should We Speak of God?May 17, 2023

Forgiveness is Too Weak a Word

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Acts 1.1-11

One of my friends, a member of my former church, spends half his year in Florida. He coaches cross-country at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. He was on a group text thread with his runners as the coaches and runners messaged each other pleas for help and advice for where to flee as they attempted to escape the school shooting in 2018. He messaged me that night to give me the names of his kids who were still in surgery, and the name of the murdered bus driver who drove the team to all their meets. He asked me to add them to the church prayer list.

“Pray for Maddie,” he messaged me, “She has a collapsed lung. She was shot in the arm and the leg and the back. Her ribs are shattered. I’m not in denial or shock. I’m not depressed. I’m just angry. I’m just really, really angry. The SOB pulled the fire alarm so he could shoot the teachers and the children as they exited. And I’m angry at the thought that the Church has nothing else to say except we’re called to forgive Nikolas Cruz for what he did. Those who would forgive apart from all his evil deeds and America’s sinful indifference being put to rights have substituted themselves for God. Whatever happened to judgment? If Christianity is nothing more than an apparatus of absolution and forgiveness, then it’s positively immoral. If that’s blasphemy so be it.”

It’s not blasphemy.

And he was not wrong.

If forgiveness is all there is to Christianity— forgiveness without judgment, absolution apart any justice, love without any reckoning with sin— then Christianity is immoral.

The New Testament scholar Reginald Fuller registers the very same point in his book Interpreting the Miracles:

“Forgiveness is too weak a word for what God does.”Grace doesn’t go far enough to describe the purposes of God.

The day after the Parkland massacre he messaged me again:

“Thoughts and Prayers?! WTF?! What’s even more galling is that as the nation grieved last night, just hours after the massacre, the NRA contracted the same operatives who circulated conspiracy theories about Sandy Hook and committed funds to an attempt to spread allegations that the Parkland student protesters— my kids— were child actors. I gotta tell you Jason, when the majority of American Christians believe that two people of the same sex kissing each other is a bigger problem than gun violence, I really can’t identify as being a Christian anymore.”

And…he doesn’t. Grace didn’t go far enough for him in order for the Gospel to sound like good news. Like Jesus today disappearing behind the clouds, he left.

But if forgiveness is too weak a word for what God does, what is the better word?Ask the average American churchgoer to describe God and he or she will almost certainly first describe God as “loving.”

This is not wrong.

It’s thin.

May 16, 2023

The Present-Tense of the Gospel

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

“If you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord…you will be saved”

- Romans 10.9-10

As Matthew Bates points out in his book, Salvation by Allegiance Alone, the word Paul uses for confess is homologeo. It means “a public declaration of fealty.” In other words, what Paul says will save you for God is the equal and opposite expression of what Rome said would save you from its wrath by confessing, "Caesar is Lord."

Notice—

Paul doesn’t say “If you confess that Jesus is the fulfillment of the promise to David (or Abraham), then you will be saved.” Paul doesn’t write that if you confess that Jesus is God incarnate then you will be saved. Nor does Paul say that in order to be saved you must confess that Jesus died for your sins.

When it comes to salvation and the necessary confession of faith for it, Paul focuses squarely on one specific stage of the gospel: The Lordship of Jesus.Why?Why does Paul fix our participation in God’s salvation to the confession of Jesus as Lord? Why not confess that God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself; believe and be saved? Why not while we were yet sinners…put your faith in what he’s done for you and you will be saved?

Why does Paul say that in order to be saved we must confess Jesus not as Savior or Substitute or Sacrifice, not as Son of Man or Son of God, but as Lord?

Because, for Paul, the incarnation and crucifixion, the resurrection and reconciliation are all past perfect events.

The present Lordship of Christ is the stage of the gospel we now occupy.What Paul summarizes as the gospel in Romans 1 he spells out in 1 Corinthians 15. The gospel he received which he in turn handed to the Church in Corinth has 8 parts to it or stages.

Paul’s gospel is that Jesus:

Preexisted with the Father.

Took on human flesh, fulfilling God’s promise to David.

Died for sins in accordance with the scriptures.

Was buried.

Was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures.

Appeared to many.

Is seated at the right hand of God as Lord.

And will come again as judge.

Note the shift. Both in Paul’s gospel and in the Apostles Creed, from the past tense to the present tense. Paul says that in order to be saved you must confess that Jesus is Lord because that’s where we are all at in the story.

It’s a non-negotiable part of the gospel:Jesus is Lord right now, currently in residence as Lord and King to whom God has given dominion over heaven and earth.To accept that present-tense point in the gospel is to acknowledge the other parts of the gospel that preceded it; likewise, to deny Jesus’ Lordship is to devalue the gospel that precedes it. The enthronement of the crucified and risen Jesus to the right hand of God to be Lord isn’t ancillary to Paul’s gospel but is the climax of it. The cross and resurrection aren’t ends in themselves; they are the means by which God establishes Jesus as the Earth’s true and rightful Lord.

As Abraham Kuyper said:

When we deemphasize the Ascension of Jesus, we immediately neuter the gospel of the only present-tense element to it.“There is not a square inch now in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ who is Sovereign over all, does not cry “Mine!””

All that remains is the gospel’s past and the future tenses. We demote Jesus from Lord of the cosmos to Secretary of Afterlife Affairs, which produces a false distinction between Jesus as a personal lord and Jesus as Lord of the Cosmos.

Salvation then becomes the promise of a future reality we access by agreeing to propositions about what Jesus did in the past rather than salvation being a present reality into which we’re incorporated by baptism and in which we participate already as subjects of the Lord who reigns now.

If this sounds like a picayune grammatical distinction, then consider the qualitative difference for discipleship:

“Jesus taught 2,000 years that we should love our enemies.”

Versus:

“The one who taught us to love our enemies 2,000 years ago is, this very moment, Lord of heaven and earth.”

Without Ascension, the Sermon on Mount can remain safely in the past, leaving us free to argue with it or agreed to it. If the Preacher on the Mount is right now Lord, suddenly his sermon becomes less about assent and more a matter of obedience.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

May 15, 2023

Your Absolution Comes from the Only Still Point in the Cosmos

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Eastertide wraps to a close this week with the Feast of the Ascension. Don’t feel guilty if you didn’t have it marked on your calendars. What was once the high holy day when Christians rejoiced that God has made Jesus King over all the nations of the Earth is now just a Thursday.

It’s not hard to see why Ascension is largely ignored. For one thing, if Christ has been given dominion over the Earth, then Jesus doesn’t appear to be doing a very good job. As Woody Allen jokes:

“If God exists, he’s basically an underachiever.”

What about the horrific war being waged against Ukraine? Yet another violent mass shooting, no doubt, in 3, 2, 1…Perhaps going from carpenter to King was too big a promotion for Jesus. Maybe that’s why we ignore the Ascension.

But surely one reason we ignore the Ascension is the embarrassing, unbelievable imagery of it.

The Ascension is the perfect example of everything that is wrong with Christianity in the modern world.

It’s a primitive, superstitious picture in a rational, scientific world.

The physics of it are all wrong. Jesus is lifted up into the air like he’s drunk too much fizzy lifting drink. Jesus, the first astronaut, going up, up, up and away, exit stage heaven. Why wouldn’t we ignore such a ridiculous image in the twenty-first century? It’s fantastical. It’s the perfect example of why it’s so hard for modern people to take the Bible seriously. To take belief in God seriously.

“Why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” the two angels ask the eleven remaining disciples. But why wouldn’t they be looking up to the sky? Isn’t that the whole problem with the Ascension? With believing in God in general? Those disciples, and the ones that came after them, the ones who wrote the creeds and compiled the canon, they believed God was “up there.” They believed the Earth was a flat, disk-shaped place around which the sun and the stars revolved.

Not only that, they believed the Earth floated on water, with the underworld below and heaven above just beyond the clouds. And it gets more embarrassing. They believed that between heaven and earth was more water, water that could inundate the Earth at any moment were it not for the firmament, seriously the “firmament,’ a sky-colored bowl that sits over the earth and holds back the oceans of universe.

It’s laughable.

And they believed in a Being who lived “up there” above the Earth. Beyond the clouds and the firmament. Up there. In heaven.

And isn’t that the problem the Ascension makes unavoidable for us? We know God’s not up there, not above the clouds, not beyond the firmament.Ascension calls BS on our unspoken secret:

we know that the God portrayed in scripture doesn’t exist. And if that God doesn’t exist, who’s to say God exists at all?

Where the disciples lived in an age where everyone believed in a God up there and disbelief was inconceivable, we live in an age where no one believes in a Man Upstairs and disbelief in God altogether isn’t just a possibility it’s the fastest growing faith in America. Maybe that’s the reason we ignore the Ascension. It reminds us that we live in a different age.

But we didn’t get here overnight. It’s been a long time coming.

In 1637, Rene Descartes, a philosopher and mathematician, helped give birth to the modern world in which we all live. Descartes was plagued by the anxiety that everything he’d been taught to believe to be true might be false. Descartes locked himself away and set out to strip away all his received certainties — even 1+1 = 2. Descartes wanted to arrive at what can be known apart from revelation. Apart from God. Where the ancient starting point for all knowledge had been God, Descartes’ starting point was himself, his own interior life.

I think; therefore, I exist, Descartes concluded. With Descartes, we became the center of the world. Not God.

And when we became the center of the world, the goal of life shifted too. From “The chief end of man is to love God and enjoy him forever,” as the catechism begins, to “the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness.” With Descartes, we became the center of the world and the starting point of all knowledge and ever since Descartes what it means for something to be “true” is that it’s true to us. To our senses. To our experience. We didn’t get here overnight. It happened so slowly we’re not even aware of how shaped we are by it.

We know what those ignorant fishermen in the Gospels do not. We know that the universe is expanding.Changing. In transition.And we know all of the galaxies in the universe are moving away from all the other galaxies in the universe at the same time. They’re moving. It’s called the galactic dispersal. We know the Earth is moving around the sun at roughly sixty-six thousand miles per hour and does so while rotating at the equator at a little over a thousand miles per hour. The universe, the stars, the earth everything is constantly moving and changing and expanding. And so are we. We lose 50-150 strands of hair a day (which is worse news for some of us than others). We shed 10 billion flakes of skin a day. 90% of the dust in our homes is made up of the dead skin we shed. We’re in transition. Every 28 days we get completely new skin. Right down to the atoms and cells, we are constantly moving and changing. Even bodies we bury in the ground keep changing; when God raises them from the dead, they will not be the same atoms they were when they were buried.

Not only do we know that there’s no firmament, we know there’s nothing “firm.”Nothing is stable or constant. Nothing is unchanging. Nothing is not in transition. Everything is constantly moving, in flux. Everything is transitory, momentary. Moving from one way of existing to a new way of existing.

But that begs the question, a question even better than the one the angels ask on Ascension Day:

If everything is constantly changing, if we are constantly changing right down to the hairs on our head and the skin that we shed, then how can we be the measure of all things?How can something in motion, something constantly changing, be the measure of anything?May 14, 2023

God is Roomy

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

1 Corinthians 15.50-56

Perhaps you have seen the serialized version of the stories on television or streamed them on BritBox, the Father Brown Mysteries. In one of G.K. Chesterton’s novels, The Incredulity of Father Brown, the detective priest rebukes a young secularist friend. According to the reverend sleuth, a modern western culture that runs its secular commitments out to their logical end condemns itself, above all, to proliferating superstitions.

Once again— the logical conclusion to secularism is not unalloyed reason (e.g., “Follow the science”) but sentimentality and superstition. In other words, the future of secularism is the past, a return to paganism, to its vision and values. In the novel, Father Brown scolds his young secularist friend:

“It’s drowning all your…rationalism and skepticism, it’s coming in like a sea; and the name of it is superstition…it’s the first effect of not believing in God that you lose your common sense and can’t see things as they are. Anything that anybody talks about, and says there’s a good deal in it, extends itself indefinitely like a vista in a nightmare. Thus a dog is an omen, and a cat is a mystery…All the menagerie of polytheism returns: dog Anubis and great green-eyed Pasht and all the holy howling bulls of Bashan, reeling back to the bestial gods of the beginning…[superstition extends itself indefinitely like a vista] all because you are frightened of four words, “He was made man.”

Or, we might add, all because you are frightened of three words, “Jesus is risen.”

The Father Brown Mysteries are fiction obviously; nevertheless, the protagonist priest’s rebuke foreshadows our present reality.

As an example of the sentimental inanity that inexorably follows secular orthodoxy, consider that four years ago Serene Jones, president of Union Theological Seminary in New York City, sat for an interview with the New York Times in which she chided those who continue to profess the faith’s dogma.

“Those who claim to know whether or not the physical resurrection of Christ happened are kidding themselves,” she said, “But that empty tomb symbolizes that the ultimate love in our lives cannot be crucified and killed.”

The empty tomb symbolizes that the ultimate love in our lives cannot be crucified or killed.

Thus, the resurrection is not an event in God’s life. It’s an orientation for our lives.

It’s not news; it’s a symbol.

It’s not history. It’s an allegory.

Only a superstitious commitment to secular ideology could produce such a nonsensical, self-refuting assertion. After all, not only is it straightforwardly in scripture (“If Christ be not raised, we are of all people the most to be pitied.”), it is brute logic. As much as a skeptic might like to say that the message of Christ’s death and resurrection is a story about unconquered love, the logic is inescapable that if Christ is not raised, then love is, in fact, conquered.

Brass tacks time—

None of us is getting out of life alive.All those who love and all those who are loved will die, and if Christ is not risen, then death—not love, not life— death has the final word. And every word you’ve spoken to a lover and every word ever uttered about you will be forgotten.It is only if God raised Jesus that love can have the final word, because only then will life have the final word. And only then will God have the final word.

The empty tomb symbolizes that the ultimate love in our lives cannot be crucified or killed. It’s a preposterous statement on its face— Jesus was crucified and killed! That such a secular piety could come from a seminary president is extraordinary indeed; however, the conviction itself is not an outlier. A BBC poll found that only 31% of Christians in Great Britain believe in the resurrection. For the two-thirds majority, the resurrection’s ethos is more important than its actuality.

I can only speak anecdotally, but, having been a pastor for twenty-two years now, I believe the resurrection is so broadly disbelieved because it is so widely misunderstood.Many dismiss the dogma and others disaffiliate entirely from the faith without having grasped what they deny. And it’s all the more critical you understand the resurrection tidings because if you look again at the creeds you will notice that it’s not one resurrection the faith invites you to believe but two.

The creeds mandate that you believe in two resurrections, Jesus’s resurrection and your own.

To have faith in Jesus Christ is necessarily to have faith that his Father will raise you from the dead. And if you doubt the latter, you disavow the former. As the theologian Karl Rahner writes, faith in the resurrection of Jesus is only fully realized— that is, you don’t really believe it— as faith in the believer’s own resurrection into life everlasting. For Paul, there is a vital and unbreakable connection between Christ’s past and your future. Notice his surprising turn of logic in 1 Corinthians 15, “If there is no resurrection of the dead,” Paul argues, “then Christ has not been raised.” It is an odd assertion. It’s a non-sequitur. Why couldn’t God raise Jesus apart from raising all of us?

Paul’s logic is sound only if the exclusive purpose of God raising Jesus from the dead is so that you will, with death behind you, join him where he lives.The logic only holds if God resurrects Jesus in order to bring you with him.

The faith invites and requires you to believe in more than one resurrection. And so it’s essential that you grasp the good news announced with that word, resurrection.

Perhaps the simplest place to begin is with verse fifty of our text where Paul distills the whole gospel into a single claim of just nine words, “Flesh and blood cannot inherit the Kingdom of God.” That’s it, the whole gospel, in nuce.

First, look at the the second clause of the statement.

Your destiny— the Kingdom of God, life everlasting, the life that is God’s own life— is an inheritance.That is—

It’s not a wage that you earn. It’s not a reward that you do or do not deserve. It’s an inheritance. It’s an unconditional gift gifted to you, simply by way of another’s death.

Your destiny— it is all grace.That’s one half of the gospel tidings.

Next, look to the first clause of Paul’s short statement, “Flesh and blood cannot inherit the Kingdom of God.”

Paul puts it in the negative, but flip it over and you’ll see it’s the other side of the gospel, and this is the side that many do not but you must understand. The life everlasting that will come to you as a free gift on account of Christ’s death will not come to you as you are presently constituted, flesh and blood.

The Kingdom of God will come to you, by grace, not as you are but as you will be, transformed into a spiritual body.That’s the whole gospel!

The future is gift.

And in it, you will be surpassingly beyond your flesh and blood body.

I mean—

My flesh and blood body— it may look sexy but it has cancer coursing through its marrow. Some of you have depression. Many of you are alcoholics.

The announcement that this flesh and blood body will live again, and will do so forever, is not good news. In fact, I think for a good many us such a message is indistinguishable from a nightmare. It’s not a promise but a threat.Many walk away from the faith or never venture near it because they believe resurrection means that Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim came back to life, as though, at some moment the air in his corpse became breath again and the still silence of the empty tomb echoed with a now beating heart.

And if this is what resurrection means for Jesus, this must be what it entails for all of us.

And of course, if this is what the church taught we should all refuse to believe it.

Because we know, a corpse’s cells do not rehabilitate neither do their amino acids rekindle. From dust you came, and it doesn’t matter how much money you throw down for a casket to dust you will return. It’s no wonder so many think the only choice is between a polarity like a literal, physical resurrection versus a metaphorical, spiritual one. It’s a false choice. They’re both wrong. Resurrection is no spiritual metaphor. And flesh can only ever belong to this body of death. It’s strange so many should think that resurrection simply refers to the dead coming back to life because this is plainly not what the scriptures teach. The resurrection is not one more event in Jesus’s life.

Scripture says the resurrection is the first fruit of a new creation, and in scripture God creates ex nihilo, out of nothing, without using any pre-existing material, like a dead body.St. Paul states explicitly what the Gospels clearly show. The first Adam, Paul says, was a living being, a mortal, material body. The second Adam, Paul writes, became a life-giving spirit. In other words, the resurrected body of Jesus is a new reality altogether, an entirely spiritual body beyond composition or dissolution. The contrast Paul sets up in 1 Corinthians 15 is not between a natural body and a supernatural one. The contrast is between two planes of existence, the terrestrial and the celestial. In other words, God has given you a body for this life and, from nothing, God will create for you a celestial body— like Christ’s— for your new home.

Your new home with him.

There are two resurrections you’ve got to believe. God resurrects Jesus in order to raise you with him into God. God descends to humanity so that we might ascend into him.

The church father, Maximus the Confessor, says that the resurrection of Jesus is a divine and divinizing event. That is, the resurrection is both a work of God upon the humanity of Jesus and also a work which brings Jesus’s humanity into God’s divinity.Likewise— and this is the mystery, and it’s a whole hell of lot more mysterious than amino acids rekindling— your resurrection will be a divine and divinizing event. Your resurrection will be both a work of God upon your humanity and also a work which brings your humanity into God’s divinity— that’s life everlasting. As the church father Irenaeus wrote in the second century:

“The Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ did, through his transcendent love, become what we are, that he might bring us [through the resurrection] to be even what he is himself.”

Irenaeus isn’t alone.

Perhaps the important figure in Western Christianity, St. Augustine wrote in the fourth century:

Resurrection is a divine, divinizing event.This divination of humanity, says Irenaeus, is what it means for death to be swallowed up in immortality."But he himself that justifies sinners also deifies them.”

And this is not merely the tradition of the church fathers, this is the clear teaching of scripture. According to 2 Peter, the aim of the Father’s work in the Son is for you and me “to become partakers of the divine nature.” Salvation is not some sort of transaction between God and humanity whereby a debt is cancelled and you are issued entry into an afterlife. No, to be saved is nothing less than to be joined to God himself in Christ. To be saved is simply to see and to enjoy what can now only be known by faith; namely, as Paul says, “Your life is now hidden with Christ (where?) in God.”

Jesus straightforwardly says this in John 14, “I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again [in the power of the resurrection] and will take you to myself, so that where I am, there you may be also.”

You will be where Jesus is.

Where is Jesus?

John told us in the very beginning of his Gospel.

Jesus is in the bosom of the eternally present Father.

You will be in the bosom of the eternally present Father.

Heaven is not a place. Heaven is a person.

And the grace and the mystery of resurrection is that somehow— without diluting his divinity, without distorting his own life— the three-person’d God can accommodate an infinite number of others into himself.You and you and you and you and you and you and you.

And me.

As Robert Jenson says, "God is roomy.” There are two resurrections you get to believe.The Father raises the Son from death. And together in their Spirit, one day, they will raise you, not to some billowy Palm Beach but into their triune life. That’s the mystery. That’s the hope.

And this is the conviction that transformed the pagan world.After all, your future resurrection into God’s own life demands I esteem you accordingly in this life and you me.Resurrection requires that I see you— view you and value you— not just as a sinner for whom Christ died but as an inextricable part of the three-person’d God. Sounding an awful lot like the fictional Father Brown, my teacher, David Bentley Hart writes about the revolution the gospel of resurrection brought to the pagan world:

“[The modern secular world spins] a simple but thoroughly enchanting tale. Once upon a time, it goes, Western humanity was the cosseted and incurious ward of Mother Church; during this, the age of faith, culture stagnated, science languished, wars of religion were routinely waged, witches were burned by inquisitors, and Western humanity labored in brutish subjugation to dogma, superstition, and the unholy alliance of church and state…All was darkness. Then came the full flowering of the Enlightenment and with it the reign of reason and progress, the riches of scientific achievement and political liberty, and a new and revolutionary sense of human dignity. This is, as I say, a simple and enchanting tale, easily followed and utterly captivating in its explanatory tidiness; its sole defect is that it happens to be false in every identifiable detail.”

The title of the book is Atheist Delusions. Hart then continues by showing how those who today wish to walk away from Christianity nevertheless carry with them values that would not exist apart from the Easter faith injecting them into the pagan world. He writes:

“In the light of Christianity’s message of the resurrection of all things into God’s own life, we came to see what formerly we could not: the autistic or Down syndrome or otherwise disabled child, for instance, for whom the world can remain a perpetual perplexity; the derelict or wretched or broken man or woman who has wasted his or her life away; the homeless, the utterly impoverished, the diseased, the mentally ill, the physically disabled; exiles, refugees, fugitives; even criminals and reprobates. To reject, turn away from, or kill any or all of them would be, in a very real sense, the most purely practical of impulses. To be able, however, to see in him or her instead a person worthy of all affection—resplendent with divine glory, evoking our love and our reverence—is to be set free from those natural limitations that pre-Christian persons took to be the very definition of reality. And only someone profoundly ignorant of history and of native human inclinations could doubt that it is only as a consequence of the revolutionary force of Christianity within our history that any of us can so regard the least among us as divine.”

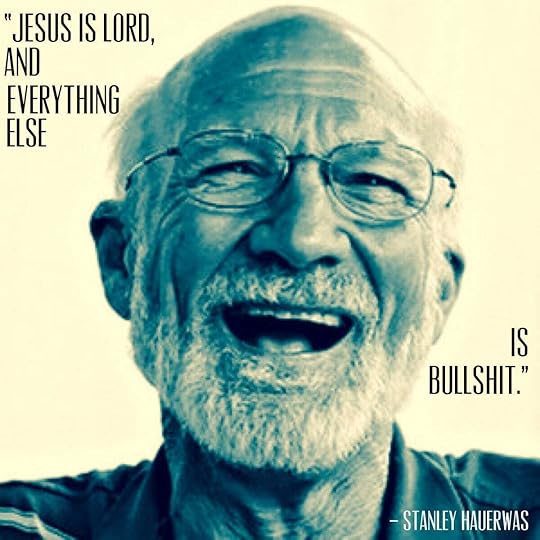

The theologian Stanley Hauerwas makes the very same point when he suggests succinctly if angrily:

Christians in America will only know that they have been faithful to the gospel if in one hundred years we are identified as the people who refuse to abort their children and euthanize their elderly.

There is much at risk in a world where fewer and fewer people are sufficiently bold to say those three words, “He is risen.”

By the reverse of that logic, our charity on behalf of the least, our compassion for the lost, our grace to the lousy— it is not natural or innate.

Rather, it all begins here, with a people gathered around the gospel.

So for their sake—

In the name of the Risen Christ, who is not the only the host of this table but is the speaker of every sermon, I summon you to faith in Christ.

Repent of your unfaith.

Trust and believe.

Jesus lives with death behind him.

And so shall you live.

With him.

In the God who is roomy.

For the sake of the lost, for the sake of the least, for the sake of the lousy and the unloveable—

In the name of the Risen Christ and on his authority, I summon you to faith in him. Because the Father has raised Jesus from the dead, your sins are forgiven.

Because the Father has raised Jesus from the dead, you are righteous in his sight.

Because the Father has raised Jesus from the dead, you are destined to partake in God’s own triune life.

Trust and believe.

Others are counting on it.

Thank you for reading Tamed Cynic. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers