Jason Micheli's Blog, page 71

July 6, 2023

That Time I Interviewed a Former Dominatrix

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here’s a video from the vault, a recording of a conversation I had for the podcast with Melissa Febos about her memoir, Whip Smart: The True Story of a Secret Life.

About the (very fine) book:

While a college student at The New School, Melissa Febos spent four years working as a dominatrix in a midtown dungeon. In poetic, nuanced prose she charts in Whip Smart how unchecked risk-taking eventually gave way to a course of self-destruction. But as she recounts crossing over the very boundaries that she set for her own safety, she never plays the victim. In fact, the glory of this memoir is Melissa's ability to illuminate the strange and powerful truths that she learned as she found her way out of a hell of her own making. Rest assured; the reader will emerge from the journey more or less unscathed.

Melissa is the author of a number of other books and is presently a professor at the University of Iowa.

July 5, 2023

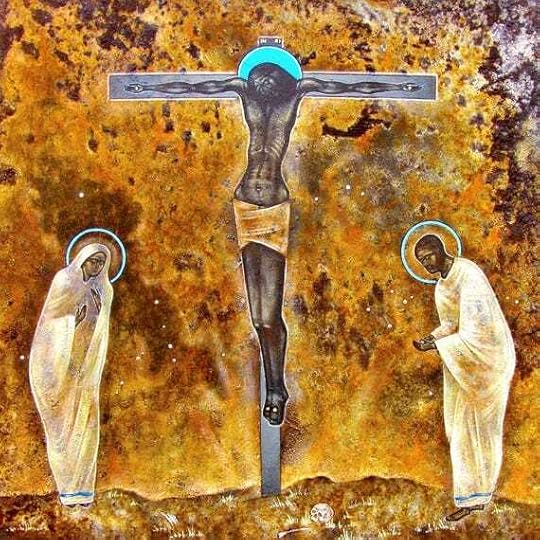

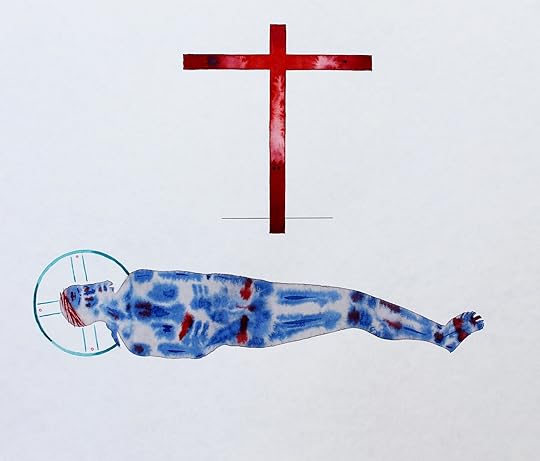

Is the Crucifixion a Penultimate Good?

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In confessing the true God to be the “creator of heaven and earth,” the dogma of the church makes a claim about the present as much as the past. As I wrote last week, the Book of Genesis makes the world’s dependence on God be independent of the difference between one moment of created time and another. God now commands everything in existence to exist. This means that what God creates is not a thing— a cosmos— but a history. God does not create a world that thereupon has a history. He creates a history that is a world, in that it is purposive and so makes a whole.

The cross is a part of the history which God creates. Is it history’s purpose?If creation is good and if its purposive good is Jesus’s Resurrection, then this implies that the Crucifixion is also a penultimate good. Likewise, if the cross of Christ is for sin, then, as conceptually and morally unimaginable as it might be, it appears that creation’s fallenness, its sin and evil, is also an intermediate good.

July 4, 2023

Grace: Mission with an Open Hand

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I just returned from a week at the White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona. With our partner, Highland Support Project, we’ve been sending service teams to build relationships and engage projects for twelve years. I’ve worked with HSP for almost twenty years now and count their founders, Ben and Lupe Blevins, important friends. In a world of greed and despair and in an ecclesial world where mission often wreaks more grief than good, I believe in HSP’s model of accompaniment for the purpose of empowerment.

I sat down with Ben at Ft. Apache and asked him to share a bit about how his understanding of grace informs the way they do their development work.

July 3, 2023

Paul Saves the Worst for Last

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The lectionary epistle for this coming Sunday is from the seventh chapter of Paul’s Letter to the Romans:

For we know that the law is spiritual; but I am of the flesh, sold into slavery under sin. I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree that the law is good. But in fact it is no longer I that do it, but sin that dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells within me, that is, in my flesh. I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I that do it, but sin that dwells within me. So I find it to be a law that when I want to do what is good, evil lies close at hand. For I delight in the law of God in my inmost self, but I see in my members another law at war with the law of my mind, making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord! So then, with my mind I am a slave to the law of God, but with my flesh I am a slave to the law of sin.

—7.14-25

The theologian Karl Barth said that preachers should approach the pulpit with the Bible in one hand and the New York Times in the other.

What Barth meant was that the world, as its described in the good news of the gospel, becomes clearer to see when you find it confirmed by and corroborated in the pages of your newspaper. The connection between the scriptures and the news couldn’t be clearer than with this passage from Paul’s epistle. Like original sin, Paul’s lament, over failing to do the good that he wills to do and failing to avoid the evil that he wills not to commit, is one of the few empirically verifiable doctrines in the Bible.

If the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Romans was a play instead of an epistle, if it was a script with a Dramatis Personae at the beginning, then it would be obvious even before you read it that in Romans, Sin has a starring role.

July 2, 2023

Christ Hold Fast

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Revelation 2.18-29

When our oldest son was in Kindergarten, my wife and I received an email from his teacher requesting a meeting. In her classroom early one morning before school, sitting across from her on tiny plastic chairs, she explained to us her concern that our otherwise cheerful and compliant child stubbornly and persistently refused to put his hand over his heart and recite the pledge of allegiance with his classmates.

“Well, what’s he do?” I asked her.

“He stands next to his desk politely and respectfully,” she said, “but— and I’ve insisted several times— he refuses to participate in the pledge.”

“Good for him,” I said, “I guess we’ve done something right as parents after all.”

“Um, excuse me? Good?””

“That’s what we’ve taught him to do,” my wife explained, “to be polite and respectful but not to participate in the pledge.”

She looked at us like we were strange.

“We of course teach our kids to love their country and to understand what makes it exceptional,” my wife added. “but we’ve also taught them not to pledge their allegiance to any other but their Lord.”

“I don’t understand,” his teacher said and, it was clear, she really didn’t understand.

“We’re Christians,” I said, “Jesus is Lord. We’ve taught them that their allegiance is to God alone. Baptism, bread and wine— those are the only pledges they ought to swear.”

“Uh, okay,” she said, “I just thought you’d want to know.

“Oh no, thanks for telling us” I said, “We’re so proud of him.”

She crinkled her eyebrows and opened her mouth furtively, “This seems like a pretty unusual interpretation. Have you talked to pastor about this?”

“We’ve definitely spoken to a pastor about it,” I said.

As we pushed back the little plastic chairs and got up to leave, she looked at us like we were the oddest people she had ever encountered.

Now, I offer that story not in order to offend some of you. And I certainly don’t share it to make me appear heroically holy. No. I divulge that story because, to my embarrassment, it is one of the only occasions when my faith has been sufficiently and publicly peculiar so as to require me to resist an allegiance other than Jesus Christ.

It’s one of the few instances when Jesus has made me weird.

The triune God is a Jealous Lord. Nonetheless, most of the time I am adept at accommodating other lovers.More often than not, I live the life of a functional atheist; that is, I seldom live so boldly that my life makes no sense if Jesus Christ does not live with death behind him. Rarely do I attempt the work of resistance and witness to which the the Spirit of Jesus exhorts the church at Thyatira.

“The words of the Son of God, who has eyes like a flame of fire, and whose feet are like burnished bronze…I know your works…your patient endurance…But I have this against you, that you tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophetess…Behold…I do not lay on you any other burden…Only hold fast until I come again.”

Endure.

Hold fast.

On September 2, 1982, Helen Woodson was arrested for pouring blood— her own blood, carried in her baby boy’s bottle— onto the Presidential flag, the U.S. flag, and the Presidential Seal during a White House tour. It was an odd, offensive, seemingly ineffective act. A self-described “Christian resister-mother,” at her trial, Woodson shared these words to the judge:

“For the past 18 years my life has been children— one birth child, 7 adopted children, and 3 foster children. Ten of my kids are mentally handicapped. We also share our home with a paraplegic Cuban refugee and with ex-prisoners and others who need shelter. All of these people are considered of little value by society. They are of no value in a society based on competition, profit, and war, yet it is these useless people who have taught me what I know of the preciousness of human life, the sacredness that transcends damage and imperfection…

Tragic death cannot always be prevented. Accident or disease may kill our children while we stand helpless to do anything. But death in war is preventable. It can happen only if we allow it, and if we allow it, we will come for judgment not before the Superior Court of the District of Columbia but before God and the murdered innocents.

The acts through which I serve life at home are considered exemplary and noble; my nonviolent witness at the White House is considered criminal. After more than two years of prayer which preceded my civil disobedience and after the 76 days I have spent in the DC Jail, I cannot, in all good conscience, see the difference between the two.”

“The words of the Son of God…I know your works…your patient endurance…But I have this against you, that you tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophetess…Behold…I do not lay on you any other burden…Only hold fast until I come again.”

Cultic propaganda surrounded the church in the ancient Asia Minor city of Thyatira. Statues and shrines, iconography and altars all declared the emperor to be the incarnation of Apollo and, just so, the Son of Zeus, the head of the pagan pantheon. It’s no coincidence therefore that Revelation’s only reference to Jesus as the Son of God occurs in the epistle to Thyatira.

If Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim is the only begotten Son of the Father, then Caesar is merely a pretender. And if a pretender, then everywhere lies and deceit engulf the believers in Thyatira.And not just Thyatira.In the Apocalypse to John, having carried the Beloved Disciple up into a vision of the heavenly throne, the Spirit of Jesus takes a name from Israel’s scriptures to describe false teachers in the church. These false teachers did more than excuse accommodation to the imperial cult. They encouraged it. And they foisted it off as a deeper, more sophisticated form of the faith. Jesus calls these teachers Jezebel. In the Old Testament book of 1 Kings, Jezebel is the pagan queen of King Ahab who manipulates her husband into introducing the worship of Baal into Israel’s devotion to the true God. In his unveiling to John the Seer, the Spirit of Jesus calls those teachers in his body who wish to mingle the piety of the nation with the lordship of Christ Jezebel.

Eating meat sacrificed to idols.

Accepting membership in Rome’s trade guilds.

Offering prayers before paganism’s fertility icons.

Pledging political allegiance to Caesar.

They’re mutually equivalent practices. They’re all component parts of a whole. They all participate in the idolatrous cult of the nation.

The danger looming over the church in Thyatira is not persecution but the avoidance of it. The temptation posed by the false teachers is the seduction of comfort and common sense— comfort and common sense rather than the counterintuitive, cruciform way of the Lamb.Jezebel presented to Christians a more realistic Christianity, one that allowed followers of the Lord Jesus to still participate fully in the social, economic, and political life of the polis. Under the guise of a deeper form of Christian faith, Jezebel was undoing what God had done to us in Jesus Christ.

Jesus is determined to make us odd.

Jezebel offers to make us reasonable.

Years later, while serving out her twelve-year prison sentence, Helen Woodson told a Washington Post reporter:

We can infer Jezebel’s effectiveness as a false teacher just to the extent that someone like Helen Woodson unsettles and offends us.“I am not surprised that you have not heard of me. For the most part, the American media is not interested in the only true power at work in the world— the non-violent acts of Christ following that hasten the Kingdom. The world wants the church instead to accommodate our faith to the world so that we can comfort the world with the illusion we are no different from the world. Or maybe the illusion is not what the world wants but what the church wants.”

Friedrich Nietzsche said the fatal problem with Christianity is that there has only been one real Christian in human history and he died on a cross. A former teacher of mine, David Bentley Hart, writes that when he finished translating the New Testament— especially the Book of Revelation— the work left him with a deep sense of melancholy along with the suspicion that most of us who go by the name “Christian” ought to give up the pretense of wanting to be Christian. Notice the distinction. He didn’t say we should give up the pretense of being Christian. He said we should give up the pretense of wanting to be Christian. “Would we ever truly desire to be the kinds of people that the New Testament describes as fitting the pattern of life in Christ?” he asks. And before you answer, consider the new way of life Christ gave his community to live.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with offenders.

By loving them.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with violence.

By suffering.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with sinners.

By eating with them.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with money.

By sharing it.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with debt.

By forgiving it.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with enemies.

By dying for them.

Christ gave us a new way to deal with a corrupt society.

By embodying the New Age not smashing the Old.

For the earliest generations of Christians, the Church was an alternative community with no second generation members, for it grew not through the family but by witness and conversion. Christians were the alternative Christ had made possible in the world through his death and resurrection. Thus, they took Christ at His word, loving their enemies and turning the other cheek and forgiving 70 x 7 times all the way to crosses of their own. Just so, Hart notes, the first Christians were “a company of extremists, radical in their rejection of the values and priorities of society not only at its most degenerate, but often at its most reasonable and decent. They were rabble, a disorderly crowd. They lightly cast off all their prior loyalties and attachments: religion, empire, nation, tribe, family and safety.”

They did so, Hart argues, because one thing that is in remarkably short supply in the New Testament is common sense.

The Book of Revelation, for example, is:

“A relentless torrent of exorbitance and extremism in which there is no comfortable median, no area of shade, for everything is cast in the harsh and clarifying light of Christ’s returning reign.”

Our passage is a clear example of such unyieldingness. To the church at Thyatira, the Spirit of Jesus lays down a strict either/or.

Either, you are allegiant to Christ the Lord.Or, your devotion is to the false idols of God and Country.Either, you are following the way of the Lamb.Or, you are acquiescing to the lure of the Dragon.

“Behold…I do not lay on you any other burden…Only hold fast until I come again.”

Everything is cast in the harsh and clarifying light of Christ’s return.

To be the kinds of people the New Testament affirms, David Hart concludes in his preface to the New Testament, we would have to become strangers and exiles, sojourners on the earth, daring to witness peacefully to the Lordship of Jesus and to resist nonviolently all others who would claim our allegiance.

Except, at least according to the Apocalypse to John, this is exactly who God has already made us in Jesus Christ. Just so, this is exactly the danger posed to the church by the teachers Jesus calls Jezebel.

A question posed by the Apocalypse is key to understanding it:

How much of our faith in Christ is wrapped up in and unintelligible without our faith in our nation and its power?

How much of our faith is actually only a Jesus-flavored expression of our politics? tribe?

How much of our faith is bound up in ethnic or racial tribes?

You’re a long way to understanding the Book of Revelation if you know that its central theme is not altogether different from Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians.The false teachers in Galatia had muddled the gospel with the law and preached a Christ + Commandments message.

Likewise, the false teachers in Thyatira muddled the gospel with civil religion and preached a Christ + Nation message.

The uncompromising conclusion Paul draws for the Galatians is the same judgment Jesus lays upon the church under the spell of Jezebel.

Christ + ______

= No gospel at all.

It’s anathema, the apostle writes. It’s God-damned.

What’s a little meat sacrificed to idols?

Where’s the harm in genuflecting to the icons of the empire?

Who’s really hurt— it’s just the red, white, and blue?

Why not go along to get along?

By accommodating their Christian faith to the piety of the nation, Jezebel’s gospel offered the possibility of Christians being good Romans.But what would make them reliable Romans is precisely what would render them suspect Christians, Jesus dictates to John. That’s the argument at the heart of this letter. Jezebel offered Christians the opportunity— the safety and security— to be reliable Romans. Don’t forget the single indictment with which Rome sent the first Christians to their deaths, atheism. The first Christians died as martyrs because, Rome charged, they were atheists. By proclaiming that Christ is Lord and America— I mean, Caesar— is not, Rome labeled Christians as atheists.

And according to the logic of the nation’s piety, Christians were atheists.Paul and Jesus both inflexibly insist that Christ + ______ is no gospel at all. Because, of course, the gospel of Jesus Christ and the civil religion of the state are very often irreconcilable with one another, and, as Christians, we cannot pretend that the will of God is unknown to us. Jesus self-attests in his letter to Thyatira. He calls himself not our Teacher or Prophet, not our Guide or Guru, not our Coach or Inspiration. He calls himself the Son of God. Thus Christians have no other recourse but to attempt lives that make no sense if God has not raised Jesus Christ from the dead and made him Lord of heaven and earth. For if Jesus is Lord, then we are his subjects. As Karl Barth said— correcting Martin Luther, “the Lordship of Christ is the article by which the church stands and falls.”

The Lordship of Christ is the article by which the church holds fast, Barth could’ve said.Holds fast or lets go.

Holds fast or gives in.

Holds fast or goes along to get along.

As Calvin says:

“Those who conceive of God in naked majesty have an idol, for God the Father wills to be known only in God the Son.”

And because the true God is not some vague, numinous transcendence onto which we can project our own prejudices and desires but is Jesus Christ, not one of us can pretend we don’t know what God wants and what God does not want.

In Jesus Christ we have received more of God’s will for our lives than any of us want to do.It’s no wonder Jezebel’s false gospel still lands upon eager ears.

Orlando Ogushoney teaches the Apache language to students, kindergarten through fifth grade, at the Theodore Roosevelt School on the White Mountain Apache Reservation. Orlando grew up on the Rez. He went on to earn multiple degrees at UC-Berkley. He taught in large, august lecture halls and worked in the boardrooms of Silicon Valley. Two years ago he returned to the Rez to teach his native tongue for a meager wage.

On Wednesday evening, I sat with Orlando at a picnic table outside the girls dormitory where our mission team was lodging for the week. The tribal schools and dormitories were a realist, progressive invention of the federal government in the nineteenth century, designed to educate indigenous youth by killing the Indian in them. Sitting at the picnic table and waiting for dinner, Orlando pointed to the second floor of the dormitory and said:

“My grandmother was raped up there. Her sisters were too.”

I said nothing, wondering if it had happened in the room where I’d slept last night.

He pointed to the boys dorm at the end of a browned-out, neglected football field and he said:

“My grandfather was ripped from there and put in the Army to fight in World War II. At the time, he’d heard neither of the war nor of someone called President Roosevelt."

Again, I said nothing.

He gestured to Fort Apache all around us.

“This place is our home. But this place is also our Auschwitz, and, I’m sorry if I’m the one to break it to you, Christians like you— you are our Nazis.”

And he pointed again to the dormitory where I’d made my bed:

“This building is monument to murder and rape, death and despair.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, unsure what else I should say.

“Don’t be sorry,” he said and wagged his finger.“Don’t be sorry. Be Christian.”I just stared at him.

“We’re the people who were ground up underneath your Manifest Destiny. And all the colonizers who came to us came in the name of Christ. They still so come. All of my classes today, every one, K-5, watched you all out the classroom windows, to see what you were doing and to wonder what you might do.”

“Why?” I started to ask.

“They watched what you were doing because you’re not the first Christians to come here. Generations of Christians have come here. And pretty much all of them have done it wrong.”

“No pressure,” I said and laughed a nervous laugh.

Orlando didn’t laugh.

“With all respect, you American Christians have almost always brought division and despair and disempowerment. You’ve raped us and you’ve robbed us and you’ve wrecked the ties that bind us, stealing our children and our language and our culture. All too often, what you American Christians have offered us is a far cry from faith, hope, and love.”

“I don’t know what to say,” I replied.

“Not saying anything, just listening to people like me, is a good place to start,” Orlando said.

I nodded.

“I’m telling you all this so you will know that most American Christians who have come to this place have been more devoted to America than to Christ. I’m not a Christian, but if you’re going to work and witness in a place like this, then, for God’s sake, think about what you’re doing. Be here, do so as a follower of Jesus and nothing else. Be here as a follower of Jesus no one else."

I didn’t realize it in the moment. He had just told me to turn away from Jezebel. He had just asked me to hold fast to Christ and Christ alone.

Orlando is a teacher now. But I’m a preacher.

Which means—

I can’t leave you where he left me. I can’t leave you with a summons.

I must hand over the goods. I’ve got to give you a promise.

So hear the good news— well, actually, first hear the bad news:

The bad news is that if we were handed a course catalog for Christianity, then we would choose Jezebel as our teacher not Jesus.Every semester we would choose her over him.Every day we do.Whether our politics are Red or Blue, every one us thinks we can mingle the blood of the cross with the stars and stripes.

This the bad, honest news about ourselves. Almost all American Christians are more American than Christian. Face it.

And hear the good news:

Christ’s offer of repentance and mercy extends even to Jezebel.1

And, just so, it extends to you too, Jezebel’s eager students.

So come to the table where bread and wine mix and mingle with no other additive allegiance. Come to the table. Take and receive your only Lord, body and blood. So having him is your best hope for holding fast to him.

Join my upcoming online class on the Book of Revelation. Register HERE . Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app1

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app12.21

July 1, 2023

Deprive Them of Their Pathos

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The cultural antagonisms unleashed by the Supreme Court’s latest round of decisions reminded me of this piece I did for Mockingbird leading up to the last presidential election.

You would never guess it from the way they greet one another along the sidewalk in the morning or wave as they jog their dogs after work, but just about everyone in my neighborhood believes America’s partisan cold war is about to ignite with fire and fury. Depending on who you ask, we are sitting on either the brink of civil war or the end of the democracy itself. They’re all angry and afraid, convinced that we have arrived at an apocalyptic inflection point in our history. Of course, you’d never know they hold these convictions with religious zeal by driving through our neighborhood. Biden and Trump campaign signs are sparse. This summer I heard none of my neighbors voice their fears or antagonize one another on the deck of our community pool. But, they do tweet them. And they share posts on Facebook with the vitriol of a WWE heel — except no one is pretending.

This may be an odd time in history, but it’s not unique.

It’s often forgotten the extent to which political propaganda and siloed partisan media outlets in Germany created the conditions that made possible the Kaiser’s war effort, the resentment and conspiracy-mongering that followed its defeat, and the rise of German nationalism. Like us, Germans were hyper-political and had politicized every aspect of their lives. Political tribalism extended into other areas of German life such that one’s party affiliation extended into every other components of social life. As Richard Evans notes in The Coming of the Third Reich:

“Choirs, sports clubs, libraries, youth groups, women’s organizations, dramatic societies — even pubs — identified themselves in political terms: as Social Democrat, nationalist, Centre, and so forth.”

German politics was a lifestyle brand, or what my friend David Zahl would call seculosity.

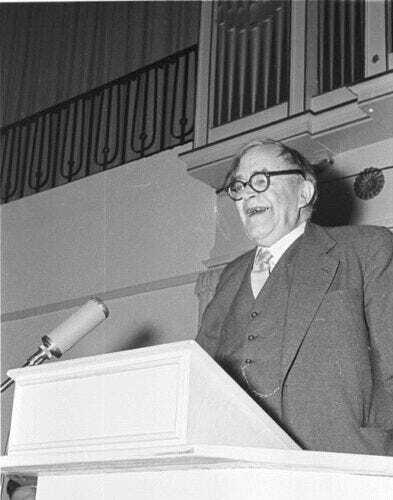

This was the climate in which the Protestant theologian Karl Barth began holding his “Exercises in Sermon Preparation” in 1932 at the University of Bonn. Barth was from Switzerland and had signed an oath to refrain from political organizing as a condition of employment in Germany, but Barth felt called to give these future communicators an alternative to the toxic and partisan rhetoric that had infected every aspect of German life.

In shaping these lectures on preaching, Karl Barth returned to his thoughts in the second edition of his commentary on Paul’s Letter to the Romans. In his exegesis of Romans 12 and 13, the question of the ethics of revolution came to the fore as Barth reflected upon the relationship between the Church and the State. To would-be activists and revolutionaries, especially Christians (rightly) dissatisfied with the status quo, Barth’s counsel bears resisting for our own fractured, Flight-93 time. Barth believed Paul’s epistle provides no justification either for reactionary, nationalistic conservatism or violent left-wing revolution. According to his reading of Romans, as Angela Hancock notes in her book Karl Barth’s Emergency Homiletic, Karl Barth argued that Christians should resist the absolute claims of the State, ideological leaders, and political parties by depriving them of their pathos. Barth writes:

It is evident that there can be no more devastating undermining of the existing order than the recognition of it which is here recommended, a recognition rid of all illusion and devoid of all the joy of triumph. State, Church, Society, Positive Right, Family, Organized Research, and so forth live off of the credulity of those who have been nurtured upon vigorous sermons-delivered-on-the-field-of-battle and other suchlike solemn humbug. Deprive them of their PATHOS, and they will be starved out; but stir up revolution against them, and their PATHOS is provided fresh fodder. (Romans)

By “pathos” Barth points back to his treatment of the word in Romans 7:5 where Paul uses the word to speak of “the sinful passions” to which we are all prone to fall captive.

The lesson is that we should not give to our party politics the passion they seek. That is, we should not invest them with eternal importance.Once given the ultimate pathos it seeks, political ideology has the power to extract from us all sorts of self-justifications that lead us in directions contrary to the good. That this is a word of caution needed by leftist and Trumpist activists alike seems self-evident. Rather than imbue politics with religious zeal, Barth writes that those who seek the common good should “do their best to prevent the intrusion of religion into that world. They will lift up their voices to warn those careless ones, who, for aesthetic or historical or political or romantic reasons, dig through the dam and open up a channel through which the flood of religion may burst into the cottages and palaces of men.”

Barth’s recommendation extends beyond ideology and politics to those who participate in them. Deprive them of their pathos; don’t give them the endorphin rush of their righteous indignation.

Don’t buy into activists’ insistence that ______ issue means we must, as Barth put it, “storm the heavens.”

With good cheer — the love of neighbor — refuse to grant the premise of their rhetoric; that is, refuse to accept that this or another political issue is an end of such ultimate, consequential stakes that any means of success are thereby justified. Political activity is important and necessary, but should be engaged as “a game that is played in full and vigilant awareness of its relativity” (Barth’s Emergency Homiletic).

In other words, to deprive them of their pathos is in fact an exhortation to extend grace, ignoring a perceived transgression and reckoning in its place a goodness that may not be present.

In 2016 and now in 2020, activists on both ends of the political spectrum have compared the voting booth to “a Flight 93 moment,” hearkening back to the brave, selfless passengers who did whatever was necessary on 9/11 to down the hijacked plane before it could wreak unimaginable devastation. To novice communicators of the gospel, in the thick of nationalistic propaganda and fascist demagoguery, Barth cautioned against exactly this sort of rhetoric that presently chokes our national discourse. It does not deprive the left of their pathos, Barth would likely say, but only ensnares them into responding in kind; likewise, seeing the defeat of President Trump at the polls this November as an existential crisis and an apocalyptic threat to America does nothing to starve his MAGA-clad fans of their sense of belonging to something ultimate. It deprives no one of their pathos to call those in one party deplorable nor to identify your own side as “the coalition of the decent.”

Barth’s thinking in Romans is a word we all need to hear. If Barth could write this in the time of Hitler (he eventually lost his post and was exiled to Switzerland), then our own circumstances do not exempt us from his wisdom. Barth was hardly a disengaged quietist, yet he worried that the measured reflection and back-and-forth negotiation required by democratic politics had been replaced by “the convulsions of revolution.” Any healthy politics must be grace in practice, for it requires a humility which is only made possible by the recognition that all participants involved are not only finite but inescapably sinful creatures. Or, as Barth puts it, politics is only sustainable when “it is seen to be essentially a game; that is to say, when we are unable to speak of absolute political right.”

To deprive them of their pathos is to reserve for God what is God’s alone, the adjudication of absolutes.Pathos — investing politics with all-encompassing meaning and identity — results, as Angela Hancock notes:

“In an escalating exchange of the political propaganda. Because their respective political views are held with deadly eternal seriousness, neither critical distance nor reasoned dialogue about politics is possible any longer.”

The neighbor who picks up my newspaper for me from the driveway is the same person who, according to Facebook, thinks people like me (i.e., people who think maybe we should talk about racism) “hate America and think only armed resistance will solve the problem.” Sarah Condon says we know now as much about social media as smokers did in the ’20s about cigarettes. One day, gasping for our last breath, I wager we’ll discover that one of the tolls taken by social media, shepherding us into ever more precisely partisan echo chambers, is that it did not allow us to do the one thing Karl Barth learned we must do when it comes to politics.

The most extended biblical meditation on the Lord’s Supper occurs in the context of Paul’s letter to the Corinthians, in which the Apostle rebukes his flock because they do not “discern the body” during the Lord’s Supper (I Corinthians 11:29). The context makes clear that by “discern the body” Paul does not mean the bread or wine themselves; he means the diversity of members that make up the Church body. Paul’s admonition to discern the body was, in Corinth, a rebuke of the way in which the Church had segregated rich from poor, male from female, spiritual from irreligious, Jew from Greek. The New Testament instructs us to celebrate the Lord’s Supper in such a way that we are forced to reckon with the nature of the motley crew Jesus draws together. To celebrate with bread and wine in a way that allows you to avoid those whom you would never choose as friends — except that Jesus has first befriended you — is to celebrate something other than the Lord’s Supper of the New Testament.

In that same meditation, Paul warns that “those who eat and drink without discerning the body of Christ eat and drink judgment on themselves.”

If there is an ecumenical corollary from sacrament to public square, then perhaps we’re all now sick from the judgment we’ve feasted upon in our politics for too many years.

And if there’s a remedy to what ails us politically, then perhaps it’s in line with St. Paul’s own prescription, to get out of our social media silos and into places where we must discern the body politic and engage it in all its diversity. Only in the latter spaces will we discover the power to deprive them, with good cheer, of their pathos.

June 28, 2023

What the Philosophers Do Not Know

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The philosopher Richard Taylor once invited readers to picture a hypothetical.

Imagine a man who is hiking in the woods and comes upon, out of the blue, a translucent sphere.

Obviously, Taylor points out, the man would be shocked by the strangeness of the object, and he’d wonder just how it should happen to be there, floating in the middle of the forest. More to the point, the hiker would never be able to swallow the notion that it just happened to be there, without cause or any possibility of further explanation. Such a suggestion would strike him as silly. But, Taylor argues (and this is money), what the hiker has failed to notice is how he might ask that same question just as well about any other object in the woods—say, a rock or a tree or a spider web or a little boy—as about this strange sphere.

He fails to do so only because it rarely occurs to us to interrogate the mysteries of the things around us.We’d be curious about a sphere suddenly floating in the forest, but as far as existence is concerned, everything is in a sense out of place.

Taylor says you can imagine that sphere stretched out to the size of the universe or shrunken to a grain of sand, as everlasting or fleeting, and it doesn’t change the wonder.

I recently started a long lectio continua sermon series through the book at the back of the Bible, the Apocalypse of Jesus Christ. Otherwise known as the Book of Revelation— its singular not plural— the Apocalypse is much neglected by some and sorely misused by many others. This need not be so, for the considerations conjured by the Bible’s vision of the End are every bit as elementary and essential as those broached by its beginning.

For example:

Creation’s Fulfillment by God in the Apocalypse invites us to realize that Genesis does not allow us to understand God’s work of creation merely as an act of initiation.The Seer in Revelation does not see that one day time will simply run out. Rather, the Spirit of Jesus shows John that in the imminent future the triune God will draw history to a close; that is, creation will be brought to completion by God.

Creation, therefore, is not that which God did once and long ago. Creation is that which God does, now and at every moment.The church’s historic liturgies confess this claim plainly.

Those who gather for Morning Prayer in my parish recite this daily in the Thanksgiving:

Almighty God, Father of all mercies, we your unworthy servants give you humble thanks for all your goodness and loving kindness to us and all whom you have made. We bless you for our creation, preservation, and all the blessings of this life; but above all for your immeasurable love in the redemption of the world by our Lord Jesus Christ.

Trinitarian dogma stipulates that anything we might profess of the Father we must also proclaim about the Son or his Spirit (e.g., The Spirit creates…The Father atones…The Son rescued Israel from Egypt); likewise, everything we can say of God’s act of creation holds true in the present tense as well. Even the stories in Genesis’s primeval history, while ostensibly narrating past events, intend to illumine present structures of life. As Robert Jenson puts it with characteristic succinctness:

“Genesis makes the world’s dependence on God be independent of the difference between one moment of created time and another.”

Quite simply—

The world would not now exist did not God now command its existence.June 27, 2023

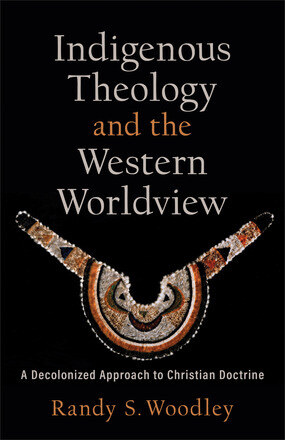

Indigenous Theology and the Western Worldview

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here’s the video recording from an upcoming podcast episode with Randy Woodley on his recent book, Indigenous Theology and the Western Worldview. I’m presently on a service team at White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona so this conversation has been in the back of my mind.

In particular, Randy addresses the question of whether it’s possible to evangelize without reproducing the problems of colonialism.

A Cherokee teacher, former pastor, missiologist, and historian brings Indigenous theology into conversation with Western approaches to history and theology.

Written in an accessible, conversational style that incorporates numerous stories and questions, this book exposes the weaknesses of a Western worldview through a personal engagement with Indigenous theology. Randy Woodley critiques the worldview that undergirds the North American church by dismantling assumptions regarding early North American histories and civilizations, offering a comparative analysis of worldviews, and demonstrating a decolonized approach to Christian theology.

Woodley explains that Western theology has settled for a particular view of God and has perpetuated that basic view for hundreds of years, but Indigenous theology originates from a completely different DNA. Instead of beginning with God-created humanity, it begins with God-created place. Instead of emphasizing individualism, it emphasizes a corporateness that encompasses the whole community of creation. And instead of being about the next world, it is about the tangibility of our lived experiences in this present world. The book encourages readers to reject the many problematic aspects of the Western worldview and to convert to a worldview that is closer to that of both Indigenous traditions and Jesus.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 26, 2023

There are Two Gods on the Way to Moriah

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Sunday’s upcoming Old Testament lectionary text is Genesis 22.1-14.

Luther was haunted by it.

Rembrandt and Chagall painted it.

In his asthmatic kitty voice, Dylan sang about it going down on Highway 61.

But in twenty years I never preached on the akedah.

Not until the Sunday after I stood outside in the church cemetery next to a shallow grave and a tiny two foot coffin tossing a fist full of dirt, I had clawed from the ground. I looked into a mother's vacant, tear filled eyes, and in the name of Jesus Christ, who is resurrection in life, I promised her— I promised her— that God did not take her child from her.

Was I wrong?

Sylvia was only four months old.

The way the undertaker had prepared her body and her mouth, she looked like she was still nursing, she'd been dressed in a coat that looked like the kind Marilyn Monroe wore on her wedding day. Next to her body. I told her parents about Jesus Christ, about how God in the flesh wept beside a grave, just like Sylvia's, wept over a friend who like Sylvia died much too soon. On a day like today, I said, it's good to remember that Jesus is weeping and Jesus is angry that any of you need to be here. I promised.

Was I wrong? Did I bear false witness?

Now is the God I promised to them, the God I promised was for them in Jesus Christ and with them in the Holy Spirit, is that the same God who tells Abraham, take your child, your only son Isaac whom you love and go to the land of Moriah and sacrifice him there as a burnt offering?

It's hard to hear Jesus saying, Abraham:

“I know I said put down the sword, but I'm gonna need you to pick it up and— really big favor— take your son Isaac and set him on fire, as a sacrifice to please and appease me.”

It's hard to hear Jesus saying what Abraham hears in Genesis 22.

And, bluntly, that's a problem.

June 25, 2023

We Don't Live in Egypt Anymore

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here’s a sermon recording from 2016 on this Sunday’s lectionary epistle from Romans 6. You can find a written (and abbreviated) version of the sermon here. It was my first sermon after a year away on medical leave for stage-serious cancer.

As always, I’m thankful for all of your time, attention, and feedback.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers