Jason Micheli's Blog, page 70

July 16, 2023

Heaven IS a Place on Earth (But It's on the Move)

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Revelation 4.1-11

On December 10, 1933, Karl Barth preached in the Schlosskirche at the center of the University of Bonn in Berlin where he was Professor of Theology. The Third Reich was only in its first year of power— elected power— but already the university, just like most of the church, had acquiesced to the racist demagoguery of an administration that had pledged to make Germany great again.

On that day in Advent, Barth stood in the university pulpit and, taking his text from Romans 15, he preached on our indebtedness as Christians to God’s primal and eternal choosing of his Israel. Halfway through his sermon, to a proud congregation who assumed they were on God’s side of history, Barth preached:

“Christ has received us, received us as a beggar is received off the street. We can even go so far as to say: we have been accepted, like an orphan is accepted into an orphanage. Christ sees us as Jews in conflict with the true God and as Gentiles living peacefully with the false gods, but he sees us both united as “children of the living God””

Christ sees us both, Barth said, quoting the prophet Hosea, united as “children of the living God.” Both races, both Christians and Jews— indeed, Jews before Christians— Christ sees us both the same, as children of the living God. Barth’s well-educated, ivory tower audience got the message. Many of them got up and walked out of the Schlosskirche right there in the middle of his sermon.

At one point, later in his sermon, Barth looked up from his manuscript and, as an aside, he lamented, “The suicides!” Everyone left in the pews knew to what Barth was referring. That year in Berlin, after the administration had quelled peaceful protests by police and military force, Germany had witnessed a rash of Jewish suicides. Karl Barth, who already had members of the Gestapo lurking in the back of his lecture hall, monitoring him, left the Schlosskirche that day in Advent, folded up his sermon manuscript, slid it into an envelope, and sent it off to Adolf Hitler.

Soon after, Barth was fired from his position and exiled back to his home in Switzerland.

Before his ouster, as soon as the university fell eagerly into the hands of the Nazis, Barth began teaching unofficial preaching classes. (Lectures later published as Homiletics.) Boredom and irrelevance in preaching can only be defeated by strict attentiveness and obedience to the biblical text, he said. “The only remedy for the bourgeois blather, urbane paganism, and sentimental nationalism that infects too many sermons was scripture.”1 The text liberates us from modern religion’s main preoccupation – ourselves– so that we can do the main business of the church, daring to listen to and talk about God.

Uniformed Nazis stood at the back of those lectures too, taking notes.

“I didn’t know that Herr Hitler had an interest in preaching,” Barth quipped jovially.When the regime finally exiled Barth back to Switzerland, his students bid him a tearful farewell, in which they asked him for a benediction.

Famously, Barth responded, “Exegesis, exegesis, exegesis.” In other words, our only hope as the world hangs on the precipice is to preach “Jesus Christ is Lord” more stubbornly than ever before.

Those same students asked the departing Barth how they, as preachers, should respond to Hitler’s dictatorship. Barth’s surprising reply confounded them.

“Preach,” Barth insisted, “as if nothing happened.”

Preach as if nothing happened.That is—

As a Christian, do not be fooled.

And as preachers, do not fool others.

The real world, what’s really going on in the world, the true state of reality— no matter what your eyes see or the headlines say— is that Jesus Christ is Lord.

“How can Adolf Hitler be a nothing?” Barth’s students wondered.

Clearly, they didn’t see whatever Barth had been shown.

And Barth warned them that the church must not allow its imagination to be captured by the world’s self-aggrandizing myths. We may resist injustice and condemn sin, of course, but in giving them our time we must not give the powers and principalities of this world inappropriate glory, honor, and dominion. We must not give to Caesar what belongs to God because Caesar’s days are numbered and the Kingdom is coming soon and, already, Jesus is Lord.

So preach as if nothing has happened.

That is—

Do not make the world’s darkness or our inveterate sinfulness more fascinating than the glad tidings that Jesus Christ lives with death behind him. The lordless powers of this world are merely provisional, passing away, dethroned by the cross and resurrection, though they haven’t yet gotten the news.

Of course, Barth conceded, Hitler’s dictatorship is a terrible “something,” but, Barth said, “the little man in Berlin is not the Lord of history.”

But to believe such a claim, to heed advice like “preach as if nothing happened,” it takes more than faith.

It requires revelation.

The old rabbis said of Israel’s scriptures that of all the books of the Bible the apocalyptic prophet Ezekiel “most pollutes the hands.” The rabbis meant that the Book of Ezekiel reveals a mystery so deep it can render the reader unfit for an ordinary world. By unveiling the knowledge of things hoped for, the prophet Ezekiel can leave his hearers fitting into time less comfortably than they did before coming into contact with him.

The same could be said of the Book of Revelation. The Apocalypse to John “most pollutes the hands” of those who come into contact it, not the least for this vision the Spirit of Jesus discloses, revealing how heaven intrudes upon the earth. As all things in creation are at once immediately available to God, the very throne of heaven was always right there, nearer to John on his prison island than his closest cell mate. In other words, the world’s reality has a dimension we cannot see unless we are shown. But once seen— and believed— it cannot be unseen.

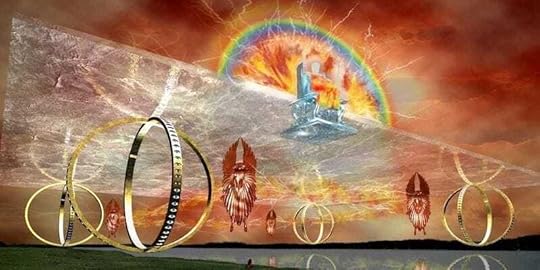

Once unveiled, the vision is as stubborn and sure as a stain on your hands that refuses to wash out.Revelation 4 ostensibly marks a shift from the “real world” to the place God makes for himself in creation, but even as the door to heaven is opened up and the Risen Christ speaks with the voice of a trumpet and the Spirit catches him up into a revelation, John’s feet remain planted firmly on Patmos. John sees the Merkahbah, the same cherubim throne shown to Ezekiel in exile with his people on the banks of the Chebar River in Babylon. Ezekiel saw above the throne “a figure with the appearance of a man” who “is the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.” Sit with the remarkable mystery. According to Ezekiel’s own testimony to it, roughly six centuries before the annunciation, Ezekiel sees Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim seated above the throne of God by the rivers of Babylon.

This vision revealed to John most pollutes the hands of those who grasp it.

Where Ezekiel describes Jesus in terms of God’s kabod, John describes the same glory in terms of precious jewels, jasper and carnelian. Just as Ezekiel saw that the throne of God is itself alive, sentient as no crafted throne can be, John reports how spirit animates the throne. Energy flows centripetally around it in the form of a cosmic liturgy, and energy flows centrifugally from it in cracks of lightening and peals of thunder. In both visions, the seers also see the rainbow— the sign from Genesis that signifies both God’s covenant of peace to Noah and God’s requirement of justice for Noah.

It most pollutes the hands.

Twenty-four other thrones surround the heavenly throne on which sit the twenty-four elders, crowned and clothed in baptismal gowns and crying holy. God is jealous but God is not miserly; God rules with the twenty-four elders who are the twelve patriarchs of Israel and the twelve apostles of Israel’s servant, Jesus. The patriarchs and the apostles enthroned around the throne. Underneath the throne, John sees, is the sea— the scriptural symbol for chaos and dread— now made still and smooth as glass.

Heaven is the place God has made for himself in his creation.Just so, heaven always intrudes upon the world.Heaven’s throne is right there, as near to John as the lock on his prison bars.That’s what John sees.

That’s the revelation.

Around the throne, on each side of the throne, John sees in Patmos what Ezekiel saw in Babylon. The living creatures. The first with a face like a lion. The second with a face like an ox. The third with a face like a human face. The fourth with a face like an eagle. According to the most ancient reading, dating all the way back to John’s own generation— take a look at the altar at the National Cathedral sometime and you’ll see— the four living creatures are the four evangelists of the gospels. Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John respectively. Their witness to the grace of God in Jesus Christ through cross and resurrection is what evokes the cosmic doxology that John hears when he sees:

“You are worthy, our Lord and God, to receive glory and honor and power, for you created all things, and by your will they existed and were created.”

Once it’s unveiled?

It pollutes the hands.

Paul says that unless we are shown the true nature of reality we can see only as through a glass dimly. Evidently, our hearing is likewise impaired. Otherwise, surely John would’ve already heard the elders’s unceasing singing.

After all, the one detail John omits, the one item he does not report from this unveiling, is any kind of journey whereby he’s transported from earth to heaven.

Just like Ezekiel by the rivers of Babylon, he is exactly where he was.

Thus, all along, the very gate of heaven was no further from him than he was to himself.

Reality has a dimension we cannot see unless we are shown.But once you see it, you cannot get it off your hands.

Some time after Karl Barth had been exiled and after the war had been ended, the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr sharply criticized Barth for failing to condemn Soviet communism.

Not one to flinch from a fight, Barth responded to Niebuhr that the Soviet project might be premised on a dangerous naïveté and it would, no doubt, prove a short-lived phenomenon but, Barth pointed out, communism’s critiques of American capitalism were nonetheless biblically warranted critiques. Besides, Barth argued, America’s self-attested, city-on-a-hill exceptionalism could very well be a greater insult to God’s glory than Russian communism. Hence, when Barth visited America for the first and only time toward the end of his life, his face having just graced the cover of Time, he made a point to visit American prisons. Throughout his career, Barth had regularly preached behind the bars of Basel’s prison. Visiting captives in America, Barth rudely, boldly noted the nasty similarity between democracy’s prisons and communism’s gulags.

Once again, Barth provoked complaint for his failure to comment on the Red Scare. But Barth only replied that he refused to be jerked around by what the world regarded as momentous issues or earth-shaking events. Barth said:

“Our greatest challenge is to deal with the shock that God has, in Jesus Christ, made our history God’s.”

That reality is the truer reality to which we should give our time and attention.

God has made our history God’s history. Just so, God has made our lives God’s life. God has made your life God’s own life. Reality, therefore, has a dimension we cannot see unless we are shown.

The Spirit of Jesus shows to John the very same throne— the Merkahbah— that the prophet Ezekiel saw. Presumably, details that only one of the two prophets describes the other prophet nevertheless witnessed. It’s the same throne. For instance, Ezekiel makes no mention of the two dozen thrones that encircle God’s throne, yet, because it is the same throne, we may conclude that Ezekiel nonetheless saw them.

Likewise, John does not include an attribute of heaven’s throne that is as vital as it is strange.

Wheels.

Heaven has wheels:

“Now as I looked at the living creatures, behold, there was one wheel on the ground beside the living creatures, for each of the four of them. The appearance of the wheels and their workmanship was like sparkling topaz, and all four of them had the same form, their appearance and workmanship being as if one wheel were within another. Whenever they moved, they moved in any of their four directions without turning as they moved. As for their rims, they were high and awesome, and the rims of all four of them were covered with eyes all around. Whenever the living beings moved, the wheels moved with them. And whenever the living beings rose from the earth, the wheels rose also. Wherever the spirit was about to go, they would go in that direction. And the wheels rose just as they did; for the spirit of the living beings was in the wheels. Whenever those went, they went; and whenever those stopped, they stopped. And whenever those rose from the earth, the wheels rose just as they did; for the spirit of the living beings was in the wheels. Now over the heads of the living beings there was something like an expanse, like the awesome gleam of crystal, spread out over their heads.”

— Ezekiel 1.15-22

This is not merely a vital detail.

It’s gospel.

Ezekiel makes it plain that however astonishing their appearance and however preternatural their capabilities, they remain wheels and— Ezekiel insists— they are rolling on the earth.

Ezekiel sees the same Babylonian dirt under the throne’s wheels as he feels beneath his feet. Just so, John saw the same soil of Patmos beneath the wheels as he felt under his own feet.Heaven has wheels. Heaven’s like a food truck or an Amazon delivery van or Barbie’s pink convertible.

Heaven’s exactly like the Knight Bus in Harry Potter— not always seen perhaps but always available and every present.This is not merely a strange detail.It’s the sort of gospel you can’t get off your hands.As Robert Jenson writes:

The division between heaven and earth, between cosmic reality and everyday reality, between the Kingdom and the world, between the Future and the present, between God’s life and our history, such divisions thus become radically problematic.

Heaven rolls along Babylonian earth.

Heaven travels on the soil of a penal colony off the coast of Asia Minor.

Like something out of the rap song “Ridin’ Rims.”

Visions are not dreams; they require the hand of the Lord. They inform about reality not the prophet’s inner reality. They are a looking at something. And, as a consequence, we who are their progeny see a reality inhabited by those who do not so see.

What do John and Ezekiel see?

And what can we see because they have been shown?

Just like Ezekiel before him, John sees God coming to judge and to save whilst in a place he might well have thought neither judgment nor salvation could reach. Neither Babylon nor Patmos are beyond the possibility of the Lord’s presence with his people. No place in the world is too far off and no situation in your life is too forsaken for the Lord to be with you and so for you.

God is not nowhere in the world.This is what both seers see.God is not nowhere in the world.

He’s on the move.

Rolling along.

Heaven has wheels.

The Spirit of Jesus says to both Ezekiel and John that what he unveils to the two prophets is “what must take place after this.” That is, the vision is a promise of the future. And because the vision is a promise from God, the promise is irrevocably unconditional. Therefore, the vision is gospel.

The vision is gospel.

On the basis of this vision, I can speak for God.And I can make a promise to you.Thus—

No matter how far off you’ve wandered, no matter how forsaken your situation appears, no matter how hopeless things seem, no matter how trapped and alone you feel, the Lord is on his way to you. Indeed he’s already closer to you than you perceive.

Will Campbell was a white Mississippi Baptist preacher and activist during the Civil Rights movement. He provoked bipartisan offense for his gospel-centered insistence on ministering to both Klansmen and their black victims. Speaking at a conference on the theme of Christianity and politics, a participant asked Campbell what he thought to be “the most significant thing going on in Washington these days.”

Will Campbell’s answer was blunt, offering just a glimpse at what we’ve been shown. Sounding like Karl Barth, Campbell said:

“There is nothing significant going on in Washington these days.”

After all, what’s so special about a stationary city on the Potomac when the Maker of Heaven and Earth is on the move in his own living motorcade?

It most pollutes the hands.

Wheels within wheels.

Jewels and white garments.

Crowns and a sea like crystal.

Six wings each and the unceasing sound of praise.

Eyes upon eyes upon eyes upon eyes.

The details are overwhelming and often inscrutable.

And yet—

All the details Ezekiel and John describe serve the restraint— the reverent reticence— you would expect from two Jews bound by the law, particularly the commandment, “You shall make no images of God.” In revealing what was shown to them, both prophets practice a still veiled unveiling. For John to reveal, for example, that the Risen Jesus appears like jewels, jasper and carnelian, is a faithful way to avoid reporting exactly what he saw and thereby making a graven image (in your mind) of God. Likewise, Ezekiel, seeing the same vision of the Risen Christ, builds in two intermediating qualifiers. Ezekiel relays that the one seated above heaven’s throne has “the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.”

What Ezekiel and John say about what they saw is also a strategy of reverent silence.They say what they say so as not to say— exactly— what they saw.Which is to say, this vision of God in Revelation 4, this theophany of the Almighty’s motorcade with all its profuse particulars, it is not as concrete and definitive as the loaf and the cup on the table.

For just as this is God’s word for you this day, God says it straightforwardly, without any qualifying intermediaries, “This is my body broken for you. This is my blood poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins.”

This theophany is a promise.

The Lord is more than on his way to you. He’s already here. He wants more than to pollute your hands. He wants himself to be placed in them.

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app1

Read Tamed Cynic in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app1Willimon, A Unique Time of God?

July 15, 2023

Sinners in the Hands of a __________ God

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Romans 8

This Sunday’s lectionary epistle is perhaps my favorite scripture, Paul’s great gospel summation in Romans 8. While I am presently doing a long lectio continua series through the Apocalypse, here’s a sermon on the text. (It’s ten years old!) I played a clip of Mark Driscoll “preaching” at the top of the sermon (“God hates you,” he screamed). Little did I know then that Driscoll was soon to exemplify, in sad fashion, the point I attempted to preach with this text.

July 14, 2023

Rethinking Faith

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Josh Patterson recently had me as a guest on his podcast, [Re]Thinking Faith. His questions come from a sincere and curious place of deconstructing and reconstructing his faith, and I was happy to share a conversation with him.

Perhaps some item in our exchange will prove helpful or thought-provoking for you.

I don’t say often enough. I truly appreciate all of you who give me space in your head and your inbox, and I’m very grateful for your feedback and support.

Before you go, be sure to sign up for my upcoming class on the last book of the Bible. It should be fun and fruitful.

We start the first Monday in August.

Sign up HERE.

July 13, 2023

The Odd Creatures of the Sixth Day

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

What do we mean when we say we're made made in God's image?

As the church encroached upon the world beyond its immediate apostolic setting, it encountered many pagans who welcomed the new gospel that Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim lives with death behind him. By raising Jesus from the dead, the true God had answered Israel’s anthropological despair. The gospel imputed a novel dignity and revolutionary value to human creatures. Just so, the proclamation of this good news— the verification that all is not vanity— created a new community comprised in no small part by categories of people previously excluded according to the religion of Plato.

It speaks to the church’s evangelical success that what the pagan world received as revolutionary, we now take for granted. “Man is made in the image and similitude of God,” asserts an early Protestant Reformer, “which distinguishes him from all other corporeal creatures.”

The tradition has made the phrase “image of God” a comprehensive attribute for the uniqueness of human beings though the rubric plays a surprisingly minor role in the scriptures.

The image of God language, eikon in the New Testament’s Greek, appears variously in the epistles:

Romans 8.29

1 Corinthians 11.7 and 15.49

2 Corinthians 3.18

Colossians 3.10

In each instance, the word eikon is not irreplaceable; that is, the dogma about human uniqueness is not the concern of the texts where the term appears. What’s more, the Old Testament speaks only once of the imago dei:

“And God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.” — Genesis 1.27

The centrality of the imago dei doctrine owes more to the church fathers’s affinity for image metaphysics of late antiquity, Robert Jenson argues, rather than to its explicit prominence in the Bible. For ancient aesthetics, “image” denoted the relationship of a work of art to its archetype. If we take the doctrine of the imago dei for granted, then we also seldom probe the question posed by this aesthetic analogy.

How do the creatures of the sixth day resemble God such that other creatures do not?What characteristics do we share— albeit analogously— with God that we do not share with other creatures such that the difference accounts for a divine resemblance? How do humans fit into time differently than the birds of the air and the beasts of the field?The tradition has ventured an answer: we are made in God’s image in that we are personal subjects as God is a personal subject. We resemble God, then, as we are rational creatures. Aquinas summarizes the tradition’s answer in his Summa,

“Such resemblance to God as can be called an image is found only in rational creatures…that in which rational creatures surpass others is intellect or mind.”

Whatever wisdom this answer possesses it is nevertheless an answer far afield from the creative address in the Book of Genesis. Another dilemma introduced by the traditional understanding of the imago, Jenson notes, is its ambiguity over whether the imago names an actuality or a potentiality. Do we resemble God by the sheer fact of subjectivity or by the qualities in which subjectivity is fulfilled?

Jenson:

“Do we resemble God by intelligence or by knowledge and wisdom? By the possession of will or by virtues? By the capacity to judge or by right judgments?”

With Aquinas, Catholic theology tends to answer with the former while the Protestant Reformers lifted up the latter. Luther believed identifying the human creature’s imago dei merely with intelligence, will, and the capacity to judge failed to distinguish the God of the gospel and it failed to account for what the human creature lost under the regime of Sin and Death.

“If it is simply these capacities that are the image of God,” Luther writes in his lectures on Genesis, “it must follow that Satan was created in the image of God.”For the Reformers, the imago dei denotes the holiness and righteousness and steadfast love that so identifies Israel’s God. The difficulty with the Protestant answer, however, is that this description in no way suits fallen humanity. And, once again, this definition of the imago dei draws a resemblance between Creator and creatures that is removed from narrative context of the only scriptural passage to make the claim of such a resemblance. The difficulties of the traditional teaching arise, Jenson argues, by failing to conceive of humanity’s specific relation to God as itself our uniqueness but instead seeking a complex of qualities, supposedly possessed by us and not by other creatures, that are claimed to resemble something in God.

Again— Definitions of the imago dei fail to attend to the passage in Genesis.

Again— Definitions of the imago dei fail to attend to the passage in Genesis.Writes Jenson:

In other words, the odd creatures of the sixth day are the only creatures whom the Lord addresses.“In Genesis, the specific relation to God is as such the peculiarity attributed to humanity. If we are to seek in the human creature some feature to be called the image of God, this can only be our location in this relation. As the relation is the occurrence of a personal address, our location in it must be the fact of our reply.”

How do we fit into time differently from the other animals?

We are those animals “addressed by God’s moral word and so enabled to respond.”

We are the creatures who resemble their Creator in no other way but that we are called to pray— pray, as the liturgy puts it, “not only with our lips but by offering up our lives as a sacrifice…”

We are the only creatures who use the word “God” as a vocative. We are made in God’s image in that we are the only creatures classifiable as “praying animals.”How we do understand the imago dei of those who do not understand themselves to pray?

Jenson answers:

“To forestall the objections that will crowd the mind, it should be noted that blasphemies, deliberately stopped ears, mindless oaths, decisions to eschew prayer and so on are all in their perverse ways prayers, together with the multitudinous prayers of religions that misidentify the addressee. It should be further noted that no responding word is instantaneous with the address to which it responds; if the response of some comes only at the Last Judgment and then is “Curse you, God,” just then they are human.”

As the triune God just is a community— a conversation— of address and reply, just so prayer is the unique and solitary way we resemble Father, Son, and Spirit. That is, by the very act of giving visibility to wishes directed beyond ourselves, we nevertheless in fact give up control and worship and, in so doing, we creatures take on the likeness of the One we beseech.

July 12, 2023

He Will Have Us, If Only We Don't Get in the Way

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Matthew 13:1-9, 18-23

Listen.

There was a man I knew in a church I once served. Andy. And if you had just one sentence to describe him, you would probably say that Andy was a hard man.

His eyes were as dark as pavement and his voice as rough as gravel. He’d been a cop, and I’ve always wondered if his jaded personality came as a result of his career or if his career choice had been a perfect fit. He was a hard man.

One time I was in my office on the phone and I heard Andy’s gravely voice in the foyer— not shouting but barking in his cop’s voice, “Get up. Get your stuff. Move on out of here. You don’t belong here.”

I hung up the phone and I went to see what the barking was about. A hitchhiker— a homeless man— had stopped at the church earlier that morning, looking not for money but for a meal. So when Andy came into the church office that day, he found this hobo seated on a dirty, green army duffel. The man was eating ham and sweet potatoes leftover from a church dinner.

The door to the church office had a little electric bell that went off whenever someone entered the building. That morning, before the bell even stopped ringing, Andy had appraised this stranger and was ordering him away, “Get up. Get your stuff.”

For Andy, the “real” world was the world he’d retired from, a world where people will do anything to get ahead and where scores are settled not forgiven. For Andy, that was the real world not the world as it’s described in stained glass places.

He’d grown up in the church…without every really becoming a Christian.

In his moments of need— when his dad had died, when he’d lost his job, when he’d struggled with alcoholism— God had not been the one he’d turned to. He had two daughters, a wife and a house. Andy was happy with his life but not grateful. And he’d be the first to admit he’d made mistakes in his life, but he’d never call those mistakes sins.

If you asked Andy if he was a Christian, without thinking, he’d say, “Yes, of course.”

If you asked his friends or his neighbors, they wouldn’t know.

Andy came to worship whenever his wife or one of his girls was singing. Every time he came he looked like he was restless to get to the main event, which for him never came.

When I preached, Andy would squint at me, suspicious of the agenda hidden beneath my words. And whenever I saw Andy sitting in the pews, I would practically throw the Gospel at him every which way, like he was target practice, hoping that some Word would take root in him. Nothing ever did.

When I heard Andy barking “Get up. You don’t belong here.” I got up and walked out to the foyer and, in my pastoral tone of voice, I asked Andy, “What are you doing?”

And Andy smiled at me like I was the most naïve child in the world and, with the man still sitting there on the duffel, he said, “He doesn’t need to be here. He’ll only bother the old folks for a handout or scare the kids.”

And I said,

My words just bounced off him like seeds on a sidewalk.“This is a church. We can’t treat him like that. Whether he bothers the old folks or not, whether he scares the kids or not, we’ve got to treat him like he’s Jesus.”

July 11, 2023

Faith Follows the Promise

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Genesis 25

This Sunday’s assigned Old Testament text is from Genesis 25 (for a recent sermon on the text, click HERE.)

As a way of avoiding the Bible’s authority and downplaying its coherence, critics often will insist that the Bible is not one, unitary book but, in fact, a library of books. And within that library called the Bible, critics will point out, there are many literary genres: histories, legal codes, gospels, liturgical prayers, primeval myths. There’s even a steamy, erotic poem.

The Bible, such critics contend, is like your Amazon Kindle; it’s a device with many different, possibly unrelated books on it.

Such a comparison is as common as it is incorrect.

By adding the story of Jesus Christ (the Gospels) and their story with Jesus Christ (the Epistles) to Israel’s scriptures, the ancient church made the assertion that the now Christian Bible tells a fundamentally connected and coherent story.

Lengthwise, from beginning to end, the Bible hangs together christologically; that is, according to Christ, who, before he is Mary’s baby, is the second person of the Trinity, eternal and pre-existent, by whom all things were made.

The Bible hangs together as a single Christological story. Or, it does not hang together at all.Therefore, Jesus Christ is the hermeneutic— the interpretative lens— by which all the Bible can be read.

Take, for example, the opening of the Jacob narrative in the Book of Genesis.

Like her mother-in-law, Sarah, Isaac’s wife does not become a mother until she is an old woman. For twenty years, the text tells us, Rebekah’s husband “prayed to the Lord for his wife, because she was barren.” Isaac— his name means “Laughter,” remember— pleaded with God for two decades, so long that his desire for a child went from no laughing matter in the beginning to what must’ve felt like a joke near the end. No one shops for maternity dresses or packs a hospital go-bag after they’ve received their AARP card in the mail.

The Israelites, whom God rescued from slavery in Egypt only after they had cried out to the Lord for generations, were the ones to write down these memories of their patriarchs and matriarchs. Surely they could resonate with Rebekah’s and Isaac’s prayers receiving a reply on such a tarried timetable. Not for nothing is the most common prayer uttered in the psalms, “How long, O Lord?”

Laughter is sixty years old when Rebekah conceives.

Rather than a normal quickening, the Hebrew says the children “clashed together within her womb.” Only, Rebekah knows that she’s pregnant with twins. Rebekah knows only that something is amiss. At her age, it would be odd not to fret.

The wife of Laughter grows afraid.

And so she prays.

She prays maybe the most common prayer ever prayed by absolutely everybody, “Why?”

“Why is this happening to me?”

And the Lord answers her!

Deus Dixit— And God spoke.

First, God gives Rebekah an explanation, “Two nations are in your womb.” But explanations are not what makes scripture hang together, and if you’ve come here today looking for answers you’ve come to the wrong place. God gives her an explanation for the commotion in her belly.

Notice—The Lord also gives her a word about the future; that is, the Lord gives her a promise.A promise that offends an ancient people’s sense of justice. A promise that turns the kin and kingdoms of their world upside down. A promise that surely sounded like foolishness and a stumbling, for it is a promise that contradicts the eternal, natural law of primogeniture.

“The elder shall serve the younger,” the Lord promises Rebekah.

You know the story.

The twins are delivered from her, one after the other, the younger clutching his hairy elder’s heel. Just so they name them, Hairy (Esau) and Heel (Jacob). But long after Rebekah last held her boys in her arms, she still held onto this promise from God, “The elder will serve the younger.” According to the text, at least forty years pass. Her children are grown men. Esau’s a married man. And everything remains as the world would have it, according to the law.

Rebekah’s an old woman, still with this promise from God socked away like a ball of rubber bands or a cigar box of old movie stubs.

Then one day, Genesis 27 remembers for us, Laughter is a very old man and very blind and very much dying. Isaac summons Esau. It’s time. Isaac must put the law into action; the eldest will not assume the father’s place.

When Laughter’s wife hears her husband aims to bless Esau, suddenly she knows. She recognizes the time has arrived for her to apply the promise. She sees God gave her the promise all that time ago— forty years— in order for her to apply that promise now.

Rebekah realizes that the promise isn’t simply a word God gave.Rebekah realizes it’s a word that needs giving.No matter how much it will upset and offend. Even though it will violate the law. Despite the cost. So she conscripts her youngest into a scheme to fool Isaac into blessing him, insisting to the skeptical Jacob, “Let your curse be on me, my son…” She takes on to herself the scorn and punishment that will justly fall upon the child for his transgression because she knows— by faith, she knows— the promise God had spoken was now seeking its moment of application. Surely she knows too that it’s a promise Jacob in no way merits. Actually he’s already earned the opposite of such a promise.

The Bible hangs together Christologically.

The promise given to Rebekah in Genesis 25 leads to Rebekah’s deceit of her husband two chapters later. Rebekah’s deceit has long preoccupied interpreters. Can the covenant rely upon a lie? What about bearing false witness? Honoring thy husband? Does this mean we’re free from the obligation to truthfulness?

The Protestant Reformers, however, were untroubled by this text. Luther called it “the faithful deceit.”July 10, 2023

The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist, and Gay Christians―and the Movement That Pushed Them Out

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here is a conversation I recently had with Isaac Sharp, author of The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist, and Gay Christians―and the Movement That Pushed Them Out.

Isaac B. Sharp is director of online and part-time programs and visiting assistant professor at Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York. He is the coeditor of Evangelical Ethics: A Reader in the Library of Theological Ethics series (Westminster John Knox, 2015) as well as Christian Ethics in Conversation (Wipf & Stock, 2020). About the book: What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear “evangelical”?

For many, the answer is “white,” “patriarchal,” “conservative,” or “fundamentalist”—but as Isaac B. Sharp reveals, the “big tent” of evangelicalism has historically been much bigger than we’ve been led to believe. In The Other Evangelicals, Sharp brings to light the stories of those twentieth-century evangelicals who didn’t fit the mold, including Black, feminist, progressive, and gay Christians.

Though the binary of fundamentalist evangelicals and modernist mainline Protestants is taken for granted today, Sharp demonstrates that fundamentalists and modernists battled over the title of “evangelical” in post–World War II America. In fact, many ideologies characteristic of evangelicalism today, such as “biblical womanhood” and political conservatism, arose only in reaction to the popularity of evangelical feminism and progressivism. Eventually, history was written by the “winners”—the Billy Grahams of American religion—while the “losers” were expelled from the movement via the establishment of institutions such as the National Association of Evangelicals. Carefully researched and deftly written, The Other Evangelicals offers a breath of fresh air for scholars seeking a more inclusive history of religion in America.

July 9, 2023

For Christ's Sake

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Revelation 3.14-22

In a sermon preached to the chapel congregation at the University of Andrews in Scotland, the theologian Stanley Hauerwas made reference to a recent philosophy course at Duke.

The class had been taught by their fellow Scotsman, the Catholic philosopher Alisdair MacIntyre. To acclimate the students to the text assigned for that day’s class, Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, MacIntyre recounted the Old Testament’s account in Genesis of the Lord’s command to Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. A student in MacIntyre’s philosophy class raised his hand, too innocent to be embarrassed by his query.

“Dr. MacIntyre,” the student coughed his voice into an adequate volume, “I confess that I have no idea what you were talking about just then.”

The Christian philosopher looked his students, now puzzled.

“The akedah,” Alisdair MacIntyre explained matter-of-factly, “in the Book of Genesis, when God summons Abraham to forsake his future by sacrificing his son Isaac.”

The philosopher then paused to see the recollection of a long forgotten Sunday school lesson creep across his students’s face. No such memory returned to them.

“I’ve never heard that story before,” the student, whose hand was still held up in the air, admitted to the philosopher.

Other students nodded and confirmed identification with their classmate’s ignorance.

So MacIntyre retold the troubling text for them, spelling out the details of the Lord’s directions. When MacIntyre finished his summary of Abraham’s near-sacrifice of his son, the student still looked dissatisfied with the story.

We do not yet know because the story begun in Abraham and the exodus is not yet ended.We do not yet know because the mighty acts of God are not over.We do not yet know because we are as much characters in the divine drama of salvation as Sarah or Moses or Mary.

The student asked the teacher, “Well, but how does the story come out in the end?”

And the teacher replied to the student, “We do not yet know.”

Similarly, the seven epistles Jesus dictates to John are messages meant for us as much as they are missives sent to the churches at Sardis or Laodicea. It is straightforwardly clear in this scripture. Each of the seven epistles in the Apocalypse are both locally addressed but universally applicable. Unlike, say, Paul’s letters to the Corinthians, which Paul sent only to the church at Corinth, the Lord bundles these seven letters and sends them out all together across the circuit of churches. In each instance, six of the Spirit’s churches would have heard the word the Spirit of Jesus had for the seventh church. Just so, these letters are meant for us as much as they’re intended for anyone.

To the extent the Fulfillment of all things is still future, the story of salvation carries on with us included in the dramatis personae.We do not yet know.

Which means—

Christ has a word of judgment for us too. The Lord Jesus has a gospel invitation for you as well. He wants to astonish your heart as much as anyone’s in Asia Minor.

He’s standing at the door.

He’s knocking.

He’s waiting.

He’s wanting.

He desires to have his body back.

Christ’s seventh and final letter to the church at Laodicea is his most famous epistle, and it is perhaps the clearest reminder in the New Testament that Jesus is the incarnation of the Old Testament’s Jealous God.

This last letter is harsh and unremittingly negative. Unlike the church at Sardis, at whom Jesus also directed considerable woe and ire, the Spirit gives no indication there is even a faithful remnant within the Laodicean congregation.

“I know your deeds,” Jesus announces, “that you are neither cold nor hot; I wish that you were cold or hot. So because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will vomit you out of My mouth.”

The King James translation captures Jesus’s urgency to distance himself from such bland, milquetoast believers:

“I know thy works, that thou art neither cold nor hot: I would thou wert cold or hot. So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth.”

In his salutation to them, Jesus identifies himself as the Amen:

“To the angel of the church in Laodicea write: The Amen, the faithful and true Witness, the Origin of the creation of God, says this…”

This is the only place in scripture where the word amen is not used doxologically, as a word of praise or affirmation. It is instead an identity. In addressing the church, Jesus acknowledges himself as the Great Amen; that is, he is the Source Material, the Originator, of all creation.

As Karl Barth put it, paraphrasing the Book of Proverbs:

“Jesus Christ is the beginning of all the ways and works of God.”As such, Jesus is primary over everything.

Unlike the six previous epistles, Jesus begins this letter to the Laodiceans with an assertion of his primal authority because the Laodiceans are not likely to agree with the Lord’s estimation of them.

The problem with the church is precisely that the church does not think that the church has a problem.We do not yet know.

Jesus’s use of creation language is not incidental.

The Lord would have us understand that the situation in the church is so dire, so far gone, so hopeless that if they are to be moved from indifference to desire, from apathy to astonishment, from death to life they need not a new discipleship program or a Sunday School curriculum but “the God who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist.”

Christ’s creation language is but a way of announcing the shocking and brutal news that, strictly speaking, there is no longer any church in Laodicea. Sure, there might be people who attend worship and contribute to an operating budget. There might be a building with a sign out front. There might be a community who tends to the poor amongst them. There might be people who welcome and include all. There might be a congregation who takes care of one another like family.

But, if they lack hearts astounded by and on fire for the gospel their situation is so dismal that they require not a reminder but resurrection from the dead.

A church that is filled with the Spirit of Jesus is necessarily a church ablaze for his gospel; conversely, a church that is not on fire for the gospel is a church necessarily animated by a spirit other than the Spirit of Jesus.Likewise, a Christian whose heart is not astonished by the grace of God in Christ Jesus is not yet (or is no longer) a Christian.We do not yet know.

Jesus intends this letter for us too.

When my wife and I adopted our oldest son, Alexander was a month away from beginning Kindergarten.

He spoke little English and his adoption from Guatemala to a couple in Fredericksburg had just disrupted after a mere few months.

They had changed their minds almost immediately and they took it out on him.

The rest of that part of the story is not mine to share.

Suffice it to say, we anticipated those first few months and years to be difficult, soul-caring work.

I made up a little song with which we would sing him to sleep, words to imprint upon him the constancy of our love.

And every night, before kissing him goodnight, we would say to him, “There’s nothing you can do to make us love you less. And there’s nothing you can do to make us love you more.”

That’s the gospel.

That’s the gospel.

God forgive us for forgetting it. God forgive us for assuming it. God forgive us for taking it for granted.

If I said that I was in love with a woman but I never spent any time with her— gave her only eighty of my minutes a week— and never told anyone else about her, never introduced anyone to her, never gave her gifts but what I had leftover, never appeared animated by anything but the dullest of passion for her and always relied on someone else to praise her, then would you be persuaded at all that I truly loved her in any meaningful sense of the word?

She would be justified in her anger.

On his way to the cross, Christ commends his followers to forgive upwards of seventy times seven. On the cross, Christ forgives those who nailed him to it, laying down his life for his enemies. After the cross, Christ comes back only to forgive the one who had thrice denied him.

Jesus can even go so far as to justify the ungodly, but for those who have lukewarm hearts for him and his gospel Jesus has no patience whatsoever.

Renown for their black wool and woven textiles, Laodicea was the garment district of the ancient world. It was one of the wealthiest cities in Asia Minor. In other words, the Laodiceans were like us. They were comparatively well-off, without any biblical needs like food or shelter or sanctuary from enemies. The Laodiceans were like us. They were comfortable and competent enough to navigate life’s challenges without the assistance of the Great Amen. The Laodiceans were like us. They were sufficiently rich to pay it forward and do some actual good deeds. Thus, in their comfort, they became convinced of and content in their own righteousness such that they no longer had any obvious need for Christ’s own alone. This is the word play at work in verses seventeen and eighteen.

Rather than the righteousness with which Christ clothed them at their baptism, with their good deeds, they believe they have clothed themselves in righteousness.From the point of view of the Great Amen, they are “poorly clad.”As good as naked. They thought they were clothed in their own righteousness. But really they’re in their dirty underwear.

There’s a reason why the gospel preaches in prisons. There’s a reason why the church grows in the third world and under regimes of oppression.

The church in Laodicea begs the same question maybe we elicit too:

Does the person who has everything— does the church who has everything— need anything from Christ and his gospel?

Jesus supplies the answer.

Here’s what you need, what I need:

repentance and forgiveness.

When it comes to Peter’s betrayal of him, Jesus can forgive at least four hundred and ninety times. When it comes to an imagined life of self-sufficiency which believes it has no need of repentance and forgiveness, Jesus can only utter woe, “I will spue thee out of my mouth.”

Jesus admits here he would prefer a community coldly set against him over one ambivalent about him. Stubborn unbelievers are better than indifferent disciples.Take me, for example. I can attest from my own encounter with him; Jesus does some of his best work with those who are hostile to him. But for those so familiar with the gospel they’re inoculated against it, the fire of their faith having grown lukewarm, Jesus says there is nothing for him to do but projectile vomit them.

Woah.

We do not yet know.

“There’s nothing you can do to make us love you less,” we used to sing to my son, “And there’s nothing you can do to make us love you more.”

Here’s the thing.

The couple who first adopted him, who quickly changed their minds and took it out on him, the song is the same for them too.

That’s the gospel.

God forgive us for taking it for granted.

Glawspel, the mix that muddles the gospel with the law, always softens the law.

But the gospel can only make alive what the threat law has killed so let us not turn this harsh and terrifying word into glawspel. Let’s allow Jesus’s word to do its damndest on us. Because the truth is, most of us are more milquetoast about Christ and tepid about his gospel than we are about a great many passions and priorities in our lives— in the church even.

And Jesus laments in this last letter there’s nothing he can do with our un-astonished hearts but eject them from his body.Or, raise them from the dead.

But for Jesus to raise the dead, he needs first to get through the door. This is what’s truly frightening. In the epistle immediately prior to this last letter, Jesus also mentions a door. To the church in Philadelphia, Jesus says the door of salvation stands open and not a one of them can shut it. They’re home free.

At the church in Laodicea, though, it’s a different door Jesus has mind.

Notice, Jesus is talking about the door of the church.

“Behold, I stand at the door [of the church],” Jesus says, “and I am knocking; if anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and will dine with him, and he with me.”

The believers in Laodicea are gathering in his name presumably and serving in his name probably and likely giving in his name, but evidently their heart was not set on him because, in all their business and busyness, without anyone noticing, they had shoved Christ clear out of the church.

Jesus wants his body back.Jesus wants back into his church.But he needs someone on the inside.He needs someone with a heart astonished enough to open the shut door and insist he come and join us.In May I taught the preaching course for the licensed local pastors in Virginia. They looked as skeptical as you all about my qualifications to be leading such a class. “It’s like the Woody Allen joke,” I told, “Those who can’t do, teach. And those who can’t preach, teach preaching.”

Before I got to the how of preaching, I addressed the what of preaching; that is, before I wasted any time offering them strategies for how to preach the gospel, I wanted to make sure they actually knew it.

I took a dry erase marker and I drew a pyramid on the whiteboard behind me. Inside the pyramid I drew lines, horizontally and vertically, to create rows and layers of blocks. I circled the triangular block at the top of the pyramid.

“This is the gospel,” I said, “the good news that Jesus lives with death behind him and therefore all his promises of grace and mercy are true and themselves open up the future as promise not threat.”

They stared at me, unsure what my picture had to do with preaching.

“The gospel is the capstone for every word of proclamation,” I said, “It’s absolutely central. It’s the point to every preached word. And it holds together every other word we might speak. Every sermon has to proclaim the gospel. Every sermon must speak for God not about God. Every sermon must hand over the goods, absolving sins on account of Christ and promising that, on the basis of his resurrection, everything is going to be okay. Everything else we might feel called to preach, everything else the text might authorize us to preach, is subsidiary to the gospel of grace.”

Once they understood the point of my illustration, they started to push back on me.

“But what about preaching on the kingdom?” one student asked, “About Christ calling us to build the kingdom.”

Rather than argue with him, I nodded and chose a block underneath the capstone and wrote a capital K.

“My people have a terrible time with their racism,” another student volunteered, “Where do you put preaching about systemic injustice?”

I turned and wrote SIN in block letters inside another brick of the pyramid.

“There’s congregational concerns too that we’ve got to address,” a second career pastor raised his hand and said, “Stewardship and discipleship…”

So I drew a steeple inside another block of the pyramid.

“How about politics and social issues” a recent seminary graduate volunteered, “Karl Barth said we should preach with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other hand.”

I pointed at her and smiled.

“You had me at Karl Barth,” I said, “But even Barth would be on board with my pyramid.”

But I turned and wrote “Current Events” in one of the blocks.

“But it can’t be the gospel every Sunday,” the second career pastor griped, “It can’t be grace and mercy and promise every time.”

I shook my head and said:

“No, every Sunday you’ve got to figure how the text authorizes you to say some form of “There’s nothing you can do to make God love you less. And there’s nothing you can do to make God love you more.”

And then I wrote it above the top triangle of my dry-erase pyramid. Just then a young man raised his head and I could tell from the slight tremble on his lower lip that he was about to make himself vulnerable.

I nodded to him that he had the floor, and he said:

“My Dad killed himself almost fifteen years ago. My brother and I found him. He went to church every Sunday. He heard a lot of sermons but I don’t know if he ever heard that on a reliable basis.”

And he pointed at the top of my pyramid.

“And I can’t help but wonder if…”

And his voice trailed off as he wiped a tear in the corner of his eye.

“I can’t help but wonder if maybe he wouldn’t have, had he heard a promise that lifted whatever burdens he had been carrying.”

There’s a reason Jesus gets so passionate over hearts that are tepid towards him.

I don’t remember that young pastor’s name. But I do know he’s someone who will kick open the shut door and let Jesus into the church.

We do not yet know.

Just before Stanley Hauerwas preached his sermon at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, soon after he climbed the steps into the ancient pulpit he heard three unmistakable sounds.

The soft thud of a door shutting.

The metallic scratch of a key turning.

And the muffled thunk of a lock closing.

The first sound Hauerwas heard got his attention, the sound of a shut door.

He turned around in the pulpit to see the wizened sexton of the cathedral.

Keys jangling in his hand, the sexton explained to Hauerwas that it was the church’s tradition, dating all the way back to the Reformation, to lock the preacher into the pulpit, and keep him there, until he had preached the gospel.

Given the Lord’s letter to Laodicea, every pulpit probably needs a locked door.

So let me make it plain and preach what I teach.

I need to hand over the goods.

Hear the good news:

The Lord Jesus does not end his epistle with law alone.

In his grace and mercy, Christ tells us what we, with our flickering flames and quenched passions, need to do.

"I counsel you to buy from me gold refined by fire,” Jesus says, “so that you may be rich, and white garments so that you may clothe yourselves and the shame of your nakedness may not be seen.”

But, if we are, as the letter indicts us, destitute wretches, then how can we “buy” such things from Christ? With what currency can we purchase Christ’s righteousness? Jesus supplies the answer in the next verse, “Those whom I love, I reprove and discipline, so be zealous and repent.”

When it comes to the kingdom, repentance is the coin of the realm.

But notice— and this is the good news; this is our only hope:

The very message the Lord Jesus gives to his church is simultaneously his means of supplying the currency for them.If repentance is the legal tender we require to cloth ourselves once again in Christ’s righteousness, then this letter itself is Christ’s means of supplying our need.

We do not yet know.

The letter is meant for us too.

The harsh and uncompromising tone of the message is the means by which Christ induces repentance in us.The good news of the gospel is that, in this harsh word of law to us with our lukewarm hearts, he is— right now— repenting us.He’s giving us, gratis, the coin of the realm.Therefore, the good news in this passage is the promise with which we ended the reading of this passage, “This is the word of God for the people of God.”

So repent.

Believe.

Believe there’s nothing you can do to make God love you less and there’s nothing you can do to make God love you more.

Repent.

Believe.

And, for Christ’s sake, someone go open the door.

July 7, 2023

Daily We Need a Do-Over

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

July 6, 2023

That Time I Interviewed a Former Dominatrix

Tamed Cynic is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and all content, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Here’s a video from the vault, a recording of a conversation I had for the podcast with Melissa Febos about her memoir, Whip Smart: The True Story of a Secret Life.

About the (very fine) book:

While a college student at The New School, Melissa Febos spent four years working as a dominatrix in a midtown dungeon. In poetic, nuanced prose she charts in Whip Smart how unchecked risk-taking eventually gave way to a course of self-destruction. But as she recounts crossing over the very boundaries that she set for her own safety, she never plays the victim. In fact, the glory of this memoir is Melissa's ability to illuminate the strange and powerful truths that she learned as she found her way out of a hell of her own making. Rest assured; the reader will emerge from the journey more or less unscathed.

Melissa is the author of a number of other books and is presently a professor at the University of Iowa.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers