The Paris Review's Blog, page 930

March 5, 2012

Loose Lips

It is perfectly monstrous the way people go about, nowadays, saying things against one behind one's back that are absolutely and entirely true.

—Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

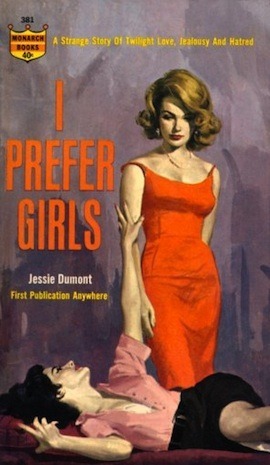

I spent a recent Sunday morning at the baby shower of a friend made in adulthood. The other attendees all went back to Catholic school, so after the obligatory oohing and aahing over the onesies, conversation turned to Jessie, the surprising no-show of the high school crowd. "She must be hungover again," said one girl with a knowing shrug.

"Yeah," another chimed in. "Scott must've been on the late shift again, if you know what I mean."

Snickering all around. "Ugh, Scott," one said with a theatrical shiver. "That guy is such a loser, my God. If Jessie doesn't move on soon—"

"Jessie will never move on," another girl emphatically interrupted. "She finds his gigantic forty-year-old beer belly and pathological fear of commitment totally entrancing, and really who wouldn't?"

What followed was another ten minutes on the subject of the absent Jessie, who, at thirty-three, all agreed, was definitely way too old to keep answering the midnight booty calls of the ne'er-do-well weeknight bartender at the Harp. Finally, the hostess noticed me nibbling quietly on my teacakes in the corner. "Oh, God, I am so sorry!" she cried. "I forgot that you don't know Jessie! This must be so boring to you—we will change the subject." A pause. "So, um, what else should we talk about?" She gazed down at her belly doubtfully.

In the thudding silence that followed, I was allowed to insist that Jessie's sleazy sexual predilections and Scott's ironic collection of too-tight NASCAR T-shirts were infinitely more interesting than bump-circumference guessing games or the extortionate price of strollers these days. Several hours past the official end of the party, I left in the glow of new friendships made: it was truly the most fun I'd had in weeks.

Because that's the thing: gossip is fun, one of the most profound and satisfying pleasures we humans are given. Read More »

March 2, 2012

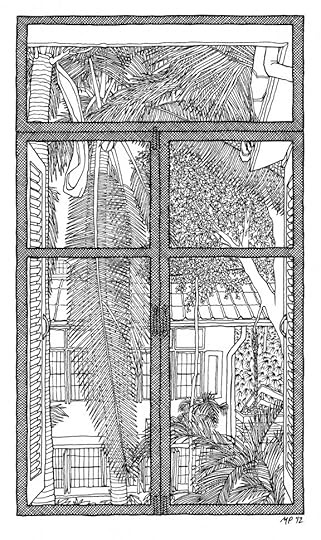

Emma Larkin, Bangkok

A series on what writers from around the world see from their windows.

My study window looks out over an incongruous jungle located in the heart of Bangkok. As the rest of the neighborhood is dominated by high-rises and townhouses that have sacrificed yards for concrete parking spaces, all remaining wildlife seems to gravitate to our garden. Myopic fantail birds tap against the windowpanes, squirrels chew on the frayed corners of the shutters, and neon-green tree snakes sunbath silently in the rain gutters. (I keep the number of a local snake catcher in my phone, as the lack of rats suggests the presence of a well-fed python somewhere in the vicinity.)

There is another type of wildness here, too. The ficus tree on the right-hand side of this drawing is where the house spirits now reside. At the advice of a fortune-teller, a tricolored band of cloth was tied around its trunk not long after we moved in. In accordance with Thai custom, regular offerings of food and flower garlands are laid out for the spirits so that they might be enticed to exist outside the house, rather than inside—a practice that has put a stop to most (but not all) of the inexplicable shadows and footsteps that flit through these old wooden rooms.

This scene encompasses both the wild and the urban, the known and the unknown. It reminds me that the dividing line between fact and fiction is less clearly defined here in Thailand and that the boundary between the two is porous. In such a place, stories thrive. —Emma Larkin

Salmon Pink; Poet Food

Dear Masters and Mistresses of The Paris Review,

Dear Masters and Mistresses of The Paris Review,

I would like to take you up on your offer for free advice. Could you, as arbiters of high taste and culture, please settle a disagreement that occurred between me and my husband this morning?

He just purchased a very nice Western-style shirt by Ralph Lauren that is clearly salmon-hued (or coral). We agree on this much. The point of disagreement comes when I lazily refer to salmon as pink. He contends that salmon is much more closely related to orange. I contend that salmon/orange/pink all derive from the primary color red and so can also be thought of as pink.

Might you have any unbiased, quasi-official information in your arsenal to settle this marital spat? Our cocktail hour this evening depends on it.

Most sincerely,

Suzanne (Austin, Texas)

For starters, why does your husband object to pink in the first place? As he doubtless knows, the association of pink with femininity is a relatively modern phenomenon, and in any case, it's the one color that can truly be said to flatter all complexions.

Those watching the pre-Oscars red carpet this past Sunday will recall that Michelle Williams's Louis Vuitton gown spawned exactly such a discourse. (Tim Gunn, to my mind, settled the debate when he came down on the side of "coral.") It's a largely arbitrary determination, at the end of the day.

Since salmon is so often twinned with the word pink, I feel safe in asserting that it is, indeed, on that color spectrum. (Although the actual flesh of the fish varies greatly in hue.) However, when you claim that orange is a shade of pink, well, you've lost me: it's a different color. So I think you both score points here.

(All that said, in my experience, whenever a man gets defensive about a garment's color and trots out "Nantucket red" or "salmon," we're dealing with pink.)

I am heading off to the last frontier (Alaska) from the crowded metropolis of New York. What books would you recommend to enhance my journey?

When I was young, my grandfather gave me a copy of Margaret Murie's Two in the Far North, an account of growing up in the Alaskan wilderness. I loved it. It's an evocative portrait of a very different time in the state, and interesting in that the author and her husband went on to found the Wilderness Society. The Yiddish Policeman's Union may bear little resemblance to anything you encounter in the actual last frontier, but it's a good read. And a friend in Juneau recommends James Michener's Alaska, Into the Wild, and, if you're a mystery fan, any of Dana Stabenow's books. (Jack London goes without saying!) Read More »

Staff Picks: Henry Darger's Room, Shelley's Ghost

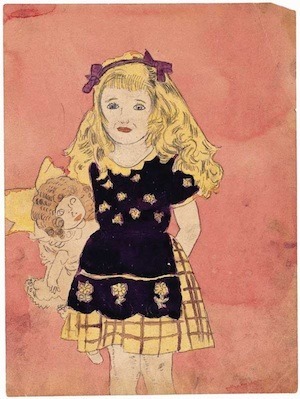

Henry Darger, Study of a Vivian Girl with Doll, mid-twentieth century, watercolor, carbon tracing, and pencil on paper, 12 x 9 inches. Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum.

"The dustbin of history was, to the revolutionary of the thirties, what Hell was to the Maine farmer. To fall out of history, to lose your grip upon its express train, to be buried in its graveyard—the conflicting metaphors descriptive of that immolation recurred again and again. But who could have believed that it could happen to so many so young?" So writes Murray Kempton in A Part of Our Time, his series of biographical essays on radicals of the 1930s. First published in 1955, the essays have lost none of their sparkle, and as a great newspaperman (who just happened, sometimes, to write like Lytton Strachey) Kempton can dash off a portrait or render an absolute judgment or paint the entire sweep of the New Deal in a matter of column inches. —Lorin Stein

I was at the New York branch of the Japanese bookstore Kinokuniya over the weekend, perusing their extensive selection of art publications, and I came across the 2007 book Henry Darger's Room. The outsider artist's work will be familiar to most people, but if you haven't seen images of his tiny Chicago apartment—left intact for twenty-five years after his death and partially reassembled in the Intuit Museum—then have a look at this volume, by his former landlords. The book is somewhere between creepy and magical. —Sadie Stein

The New York Public Library's exhibition "Shelley's Ghost" is a pleasant place to spend an hour after lunch if you happen to be in midtown. You can examine "Ode to the West Wind" and "Ozymandias" as well as Laurence Olivier's copy of The Cenci (he once contemplated a production). There are also a few Shelleyean relics, some cute and some a little creepy: the poet's gold-chased baby rattle, his Neapolitan guitar (see "With a Guitar, to Jane"), and some fragments of skull that survived his cremation near Viareggio. —Robyn Creswell

Angela Carter's The Bloody Chamber, a collection of dark and sensual feminist fairy tales based on traditional legends, has me spellbound. —Elizabeth Nelson

The entire collection of love letters between Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning were put online earlier this month. They aren't exactly tied in a pink ribbon, but they are fascinating to browse. —Deirdre Foley-Mendelssohn

This Is Not a Film, a collaboration between Iranian filmmakers Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtamhmasb, opened this week in New York. Made right before Panahi was sent to an Iranian prison on a six-year stint for antigovernment propaganda, the movie is a portrait of a filmmaker in crisis, a yawp over the roofs of the world. —Josh Anderson

I'm just saying: The Room is playing this Saturday at Landmark Sunshine. Get your spoons out. —S.S.

March 1, 2012

On Press with 'The Paris Review'

How good is our two hundredth issue? So good that Matt, an operator at the Sheridan Press, accidentally let slip about five hundred sheets from the press—get this—while he was reading a few pages from our interview with Bret Easton Ellis. "I didn't know he'd written so many books," Matt explained. "I was reading this article and didn't look up for a few minutes."

(We don't blame you, Matt. It's a damn fine interview.)

Managing editor Nicole Rudick and I are in Hanover, Pennsylvania, on our quarterly trip to the Sheridan Press, where our latest issue is running hot off the presses. We usually hole up for the day in the "Library"—it's far enough away from the actual printers that we can't cause much trouble—but this time Todd, Sheridan's prepress manager, was kind enough to take us around for a tour.

A Heidelberg press printing the cover of issue 200.

Alberta Sings the Blues

I never really got the Blues, though I have certainly gotten the blues. Maybe that's why, until recently, I had never heard of Alberta Hunter, and why her recordings and I are now inseparable. If Bessie Smith's blues are a wail to the world, Alberta's are a conversational tête à tête. She wrote and sang throughout her life, but refused to be classified as a singer of any particular genre. "Just call me a singer of songs," she insisted.

Last summer, a pianist friend handed me Amtrak Blues, an album Alberta recorded in 1978, at age eight-three. "You'll get this," he assured me. When I put it on, a frank, earthy voice radiated from the stereo speakers, and I started wondering who this lady could be. I found photos of a moon-eyed Chicago saloon singer with gold hoop earrings, a Parisian flapper in a filmy evening dress, a nurse in whites, a USO entertainer in khakis, and a sibylline old lady.

There was, as it turned out, a variegated life behind such variety. "I've been more places by accident than most people have been on purpose," Alberta once quipped. A singer, actress, composer, and journalist, she was a kind of musical Marco Polo whose talents were as diverse as the many places her career carried her. Read More »

February 29, 2012

On the Shelf

R.I.P. Jan Berenstain.

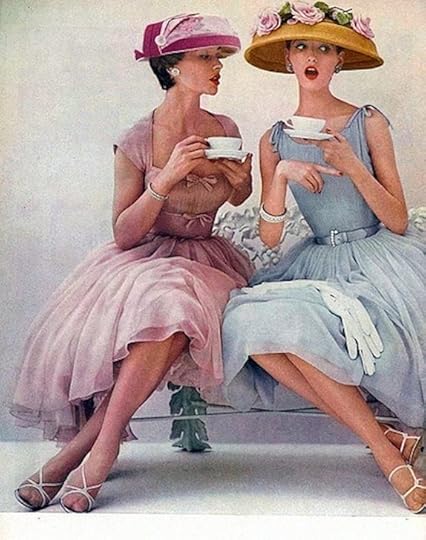

Pulp fiction.

Bad blurbs.

Retaining reading.

The case of the Agatha Christie estate.

Garden & Gun vs. The Oxford American .

Jackie Collins takes matters into her own hands.

Gillian Anderson takes on the lost Brontë.

"A guide to Estonian socks, an examination of the role of the fungus in Christian art, and a celebration of the humble office chair" are just a few of the entries in the Diagram Prize for Oddest Book Title of the Year.

Our man in Vienna.

Levity for Leap Day!

Barney Rosset to get the posthumous treatment?

A man's world?

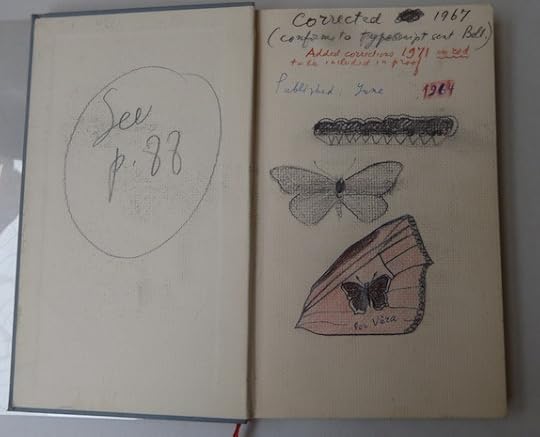

Document: Nabokov's Notes

When Vladimir Nabokov started teaching Russian literature at Wellesley College in 1944, he was frustrated by the lack of an adequate literal translation of Eugene Onegin, which he referred to as "the first and fundamental Russian novel." He prepared his own extracts for class use and invited Edmund Wilson to work with him on a full translation.

Wilson had nurtured Nabokov's early career in the States, and Nabokov had reciprocated with many generous hours of patient tutorial—often via letter—on the finer points of Russian literature, history, politics, and scansion. The two had grown to be great friends but never collaborated on a full-length work. The 1964 publication of Nabokov's solo translation of Onegin effectively ended their friendship and sparked one of the best-known intellectual debates of the last century.

The project began promisingly enough for Nabokov, though Wilson had misgivings from the get-go. When Nabokov first decided to prepare a prose translation of Onegin, "with notes giving associations and other explanations for every line," Wilson and Nabokov had been exchanging letters about Russian poetics for a decade, often with barely masked stridency on both sides. In 1950 Wilson expressed fatigue: "I am getting rather tired of all these topics and think we ought to start something new." When he learned that Nabokov has decided to devote his Guggenheim Fellowship—achieved, in part, through Wilson's recommendation—to the Onegin project, he complained: "I wish you had given them some other project—it seems to me a pity for you to spend a lot of time on Onegin when you ought to be writing your own books." Nabokov, however, wasn't worried: in his application he wrote that it would take "a year or so," and told Wilson the work could be "quite smoothly combined with other pleasures."

A year later he wrote how much more arduous a project it had turned out to be: "I was … on the verge of a breakdown and not fit for company. For two months in Cambridge I did nothing (from 9 A.M. to 2 A.M.) but work on my commentaries to EO." Still later, it seemed he had met his whale. He wrote to Katharine White, his friend and New Yorker editor, that the "monster" had "grown far beyond whatever I planned originally." He told Wilson, "I have at last discovered the right way to translate Onegin. This is the fifth or sixth complete version I have made." At the end of the summer of 1957 he admitted more confidentially to his sister, "I hope that I can finally, finally finish my monstrous Pushkin … I am tired of this 'bookish exploit'." Read More »

February 28, 2012

The London Library

Once a month or so when I was a small boy, my father and I would spend a Saturday morning together in the St. James's area of London, later meeting my mother and sister for lunch at a restaurant close by. The routine, which never varied and whose endpoint was always the same, started with a haircut at a Turkish barber's above a clothes shop on a busy shopping street.

Descending into the world again, with newly cut hair, the facades of Jermyn Street—brassy, glazed, filled with the refined and adult promise of brogues, horn-handled hairbrushes, and silk pajamas—stretched left and right before us. Around the corner, through a short flurry of alleys, we came to St. James's Square: home, in the northwest corner, to our destination, the London Library.

The library building is tall and slim, squashed into the corner between a stately townhouse and the Cypriot Embassy. My first impression of the place was of disjunction; inside and outside do not match up. In a third-story window, an owl perches on the sill (further inspection reveals it to be a decoy). In the stacks, through the latticed metal walkways, as in Borges's The Library of Babel, "you can see the upper and lower floors, endlessly." In the fifteen miles of shelving, desks appear at random, with or without a corresponding chair; members and librarians flit past, fragmented faces visible through rows of books. My father and I never stayed long, fifteen minutes or so at most. We returned his books to the librarians, picking up any that had been set aside, and then flung ourselves like hunters into the warren of the stacks.

I joined the library for myself when I was about eighteen and soon the place became an addiction, an obsession. In the summer before university, when many of my friends were embracing their new freedom on beaches or riding trains across Europe, I explored those corridors, picking out books with titles like The West of Buffalo Bill, and Ten months among the tents of the Tuski: with incidents of an Arctic boat expedition in search of Sir John Franklin, as far as the Mackenzie River, and Cape Bathurst. I chose at random. I found, and reveled in, shelving sections like "S. Devil &c.," "S. Fingerprints," "H. Exhumation," "T. Hints for Travellers," "S. Flower Arrangement," and my favorite, "S. Fools." Read More »

Helen Simpson on 'In-Flight Entertainment'

Helen Simpson. Photo by Derek Thomson.

I met Helen Simpson for a genial pub lunch near Dartmouth Park in North London on the day she received the American edition of In-Flight Entertainment. She was evidently quite pleased by the book's spare but elegant design, which looks through an airplane window onto a locket of cerulean sky. I'm tempted to draw comparisons to her stories, many of which peek at other people's blitheness, or cruelty, or dreams of escape. But nothing in Simpson's fiction is quite as peaceful as that glimpse of blue. She is perhaps best known for the characterization of contemporary motherhood in her collections, but many of the stories in In-Flight Entertainment confront the prospect of climate change.

Your collections are never quite themed, but they do feel very painstakingly designed. Was that true for In-Flight Entertainment?

In-Flight Entertainment is my little climate-change suite, I suppose. But there are fifteen stories in it, and only five are about climate change. My only rule is to write about what's interesting to me at the time. It's a great subject, but it's very hard to dramatize or to make particular, and not to hector, not to moralize.

There are plenty of experts in these stories. There's Jeremy in the title story as well as amateur researchers like Angelika in "The Tipping Point" and G in "Diary of an Interesting Year." They don't seem to benefit from their knowledge.

Well, it alienates people from them. That's the trouble. Did you ever watch that episode of The Simpsons shortly after Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth came out? It is spoofed as An Irritating Truth. It is an irritating truth and no one wants to hear someone sounding off about it, and particularly not when they're about to go on holiday.

Stories are good for uncomfortable things, for uncomfortable subjects. They're not generally relaxing. Novels are more relaxing. You just give up to the novel, you go into its bath, you submit to it. You don't with a story. You're more alert as a reader, and more critical. If it doesn't grab you by the second sentence, it's done. Whereas with a novel, people will give it a couple of chapters before they abandon it. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers