The Paris Review's Blog, page 927

March 23, 2012

After-College Angst; Getting Undepressed

This week our friend Sasha Frere-Jones was kind enough to share his good counsel. By day, Sasha is the pop critic for The New Yorker, and by night he is a member of the bands Calvinist and Piñata. By day or night, he gives darn good advice.

This week our friend Sasha Frere-Jones was kind enough to share his good counsel. By day, Sasha is the pop critic for The New Yorker, and by night he is a member of the bands Calvinist and Piñata. By day or night, he gives darn good advice.

Lately I've been watching a lot of after-college angst films. Kicking and Screaming by Noah Baumbach and St. Elmo's Fire by Joel Schumacher more than any others, though there are others. Anyway, I'm currently studying writing in Chicago, and with graduation just around the corner I've been wondering about novels that focus on this time period, or perhaps even nonfiction. I realize there are many college novels, and books about people who have in fact received diplomas from various universities, but I'm wondering more about books that focus purely on that new onset of confusion immediately after leaving the comforts of academia.

Try Sheila Heti's How Should a Person Be? and Elaine Dundy's The Dud Avocado. Dundy's book is set in 1950s Paris, ground zero for Madcap Hijinks. A young woman named Sally Jay Gorce larks about, alternating between enthusiastic musing and socially inept hedonism. Some of the comedy is too arch, like a Jack Lemmon movie with too much mugging, but Gorce is as likable as Lemmon. Dundy's sentences are rhythmically subtle and easily devoured. It is not a bad thing to be reminded that your postcollege years can be infinitely ill-considered without doing too much damage.

How Should A Person Be? is the inverse of The Dud Avocado. The book's form is fluid and unpredictable: lists are followed by dramatic dialogue, and a fair number of pages are devoted to a competition between friends to see who can create the worst painting. The architecture gives the prose a circular, easy feeling, even though Heti is taking a hard look at what makes life meaningful and how one doesn't end up loveless and lost. It is book peopled by twentysomethings but works easily as a manual for anyone who happens to have run into a spiritual wall. (Heti's book is out in Canada now, but will be released here in June. The American version will be different, because Heti herself wanted to modify the text, a fairly unusual thing in fiction.)

Dear lovely Paris Review,

Could you let me know of a few books, written between 1790 and 1930*, that will make me undepressed? I don't mean a book that's necessarily funny or optimistic, usually those throw me even deeper into depression—I mean something that's going to legitimately make me see the world through someone else's completely fascinating or biased or hyper-judgmental or abstract vision of it so that I can leave my own consciousness for a bit? Or even a book that puts depression into perspective.

Thanks,

Henry

*I add a time constraint because I would like to read books that were written before depression was labeled as such, or diagnosed.

I can't promise that either of these books will cure depression or induce happiness—enormous tasks—but both are fantastic and are narrated by protagonists living in fractured worlds. Emilio Lascano Tegui's On Elegance While Sleeping was published in 1925, and is as far from self-help psychobabble as fiction gets. The protagonist, Meursault, is entirely unreliable, and that is not a failing. He wanders, apparently syphilitic, through a French village at some point in the nineteenth century. He witnesses acts of depravation and plans, in a leisurely way, to commit murder. The book is brief and compressed, with the blurred edges of a dream, and the perversity of the characters is matched by the economy of Tegui's prose. The present moment seems pretty timid after spending time in Meursault's mind.

Fernando Pessoa did not exactly write The Book of Disquiet, which was assembled from various scraps and published long after the author's death in 1935. The fragments that make up this book are attributed to Bernardo Soares, one of Pessoa's several alter egos, or "heteronyms," as he called them. Soares seems almost identical to Pessoa, from what we know, and this work chronicles the life of a flaneur in Lisbon, walking, worrying, assembling, and disassembling his own psyche. Read More »

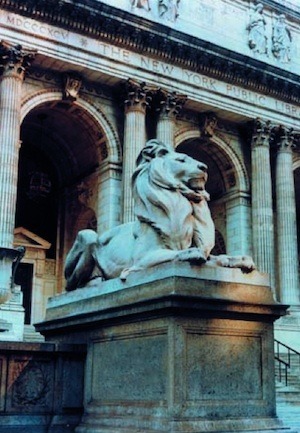

Staff Picks: Whither the Library, Mafia Men

Like many editors and critics, I depend on the New York Public Library because it has the books I need when I need them—whether it's an obscure edition of Les Fleurs du Mal or a monograph on Mary Lamb—and because it is one of the few places in New York where anyone can work in peace and quiet, and with free help from experts in their fields. Now there are plans to overhaul this unique institution and tear out seven floors of stacks. Scott Sherman and Caleb Crain make me wonder why. —Lorin Stein

Like many editors and critics, I depend on the New York Public Library because it has the books I need when I need them—whether it's an obscure edition of Les Fleurs du Mal or a monograph on Mary Lamb—and because it is one of the few places in New York where anyone can work in peace and quiet, and with free help from experts in their fields. Now there are plans to overhaul this unique institution and tear out seven floors of stacks. Scott Sherman and Caleb Crain make me wonder why. —Lorin Stein

"The Mafia is the consciousness of one's own being, the exaggerated concept of one's individual strength, the only arbiter of every conflict of interests or ideas." So wrote Giuseppe Pitrè, a nineteenth-century scholar of Italian folklore, and so opens Cosa Nostra: An Illustrated History of the Mafia, which landed on my desk this week. It's strewn with more bars, cops, and bloody corpses than the best crime movie. —Deirdre Foley-Mendelssohn

The Keith Haring show just opened at the Brooklyn Museum, and though I haven't made it out there yet, I've been following the museum's Tumblr blog featuring selections from Haring's journals. They're putting up a page each day, and most so far are from the early seventies, when he was a teenager, but some of the site's earliest posts show Haring playing around with ciphers and visual repetitions—hints of what is to come. —Nicole Rudick

Ron Padgett and John Ashbery discuss the life and work of Frank O'Hara in this recent conversation at Harvard. The bittersweet reminiscences include O'Hara's introduction to Larry Rivers at a party. To hear Ashbery tell it, it wasn't long till they were canoodling behind a window drape. —Josh Anderson

I was recently blown away by Under the Volcano, Malcolm Lowry's famous account of a day in the life of a British Consul suffering from latest-of-late, DT-stage alcoholism. The Consul, one Geoffery Firmin, has reached that fatal apex of the disease in which reality splinters into an inscrutable funhouse, and the quotidian becomes demonic. The vivid depiction makes a sad kind of sense, for in many ways it was a porthole into the late Lowry's own troubled mind. (Although it must be noted that Volcano's tragic star is also totally hilarious.) Even if you haven't read Lowry's work, you can watch the entire 1972 Oscar-nominated documentary about his life here for free. It is truly fascinating. —Allison Bulger Read More »

March 22, 2012

"'Summertime and the Living…'"

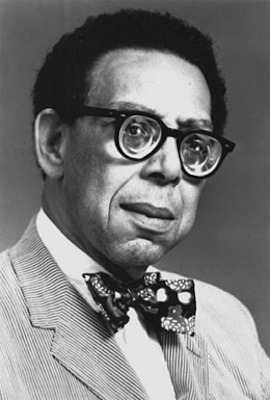

Robert Hayden.

One of the pleasures of reading a great poem over time is the way its meanings establish themselves (like the "trees of heaven" that reclaim the space of "quarrels and shattered glass") and grow sturdier, larger.

I first read Robert Hayden's "Summertime and the Living..." at an age where I neither understood ellipses nor was hip to the signals of quotation marks. I had scarcely heard of Porgy and Bess, so I missed entirely the allusion to "Summertime" the song. Instead, I thought of the poem as situated in memory, as a man looks back on a boyhood imprinted by the "Mosaic eyes" of those elders to whom "the florist roses that only sorrow could afford long since have bidden ... Godspeed." If I had known that the next two words indicated by the title "Summertime and the Living..." would be "is easy," I no doubt would have (knowing what a predilection I then had for irony) seen the poem as a quick "gotcha," an "oh you thought it was this but it was that" kind of poem, and I imagine it would have taken longer for me to appreciate its nuance. But I was first reading the poem at that tender time when I still took it on faith that nearly all poetry is born of sincerity, and I missed Hayden's sly joke. It was that sly.

Later, I heard the song. Later, I saw the deft choice in every word. The way "gangled" worked off "vivid" which worked off "unplanned" to suggest a lively disorder out of which dream emerges in the form of "circus-poster horses." And later still I saw the roses not as a decorative flower (as I'd once imagined them) but as a necessary embodiment of sorrow exceeding frugality in its expensive claim on our hearts. Later, I understood the symbolic power of boxer Jack Johnson setting "the ghetto burgeoning with fantasies" as he leaves in a "diamond limousine." Read More »

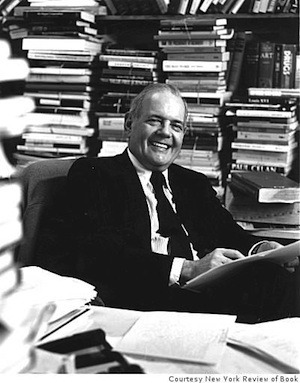

Robert B. Silvers, Super Nanny

This year our Spring Revel will take place on April 3. In anticipation of the event, the Daily is featuring a series of essays celebrating Robert Silvers, who is being honored this year with The Paris Review's Hadada Prize.

This year our Spring Revel will take place on April 3. In anticipation of the event, the Daily is featuring a series of essays celebrating Robert Silvers, who is being honored this year with The Paris Review's Hadada Prize.

Writers dream. They dream more than most people. Writers dream of sex, of fat advances and big sales. They dream of fame. When they get serious, they dream of being published by the ideal publisher and being edited by the ideal editor. From 1993, when he bought my first novel, Wartime Lies, until October 2002, when he died, shortly after publishing my sixth novel, Schmidt Delivered, Siegfried Unseld, the head of the German publishing house Suhrkamp Verlag, was my ideal publisher. A giant of a man, Siegfried loved books passionately and physically, the way other men can love wine. Siegfried didn't publish books, he published authors. A writer lucky enough to be one of them could feel invulnerable: Siegfried believed in his work, and Siegfried couldn't be wrong.

I have long been afflicted on and off by "regular contributor" envy, wishing disconsolately that in the list of writers whose names appear in The New York Review of Books my name were followed by that tag. It's an absurd pretension, since its fulfillment would have meant upending my life and career. I suffer from it only because the ideal editor of my—and I would guess every writer's—dreams is another giant of a man, Robert B. Silvers, the editor, brain, and heart of the NYRB. When I write a piece for his magazine, of course I have the immeasurable good luck to be edited by him. There is no experience quite like it. Bob knows everything that's worth knowing, a consequence of his unflagging curiosity. I recall sitting next to him years ago at a Council on Foreign Relations meeting. While the energy minister of an OPEC country, the name of which I have forgotten, droned on, I stole a glance at Bob, who could no doubt recall it instantly. He was busily taking notes, in a tiny but precise scrawl. My mind was in neutral, in fact I was struggling against sleep; his was fully engaged. Later he told me that taking quick and accurate notes was a habit he'd formed soon after college, working for the Connecticut politician and diplomat Chester Bowles. It's just one of his useful habits, along with reading everything that deserves his attention and deploying, when the occasion presents itself, a powerful crawl stroke. Read More »

March 21, 2012

On the Shelf

The history of English in ten minutes.

(Courtesy of Reddit!)

Bei Ling: "I was amazed that no independent voice, no exiled or dissident writer from China is being represented at the London Book Fair."

Dystopian dream books.

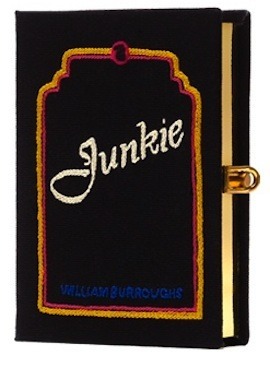

Junkie: the It bag for spring!

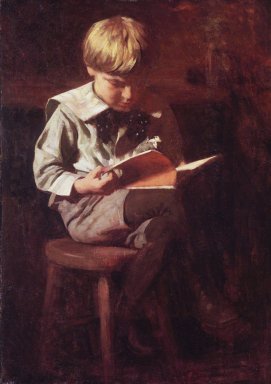

This is your brain on books.

Remembering Joe Brainard.

"The centrepiece of our brand new displays in Solo Gallery is Roald Dahl's Writing Hut, complete with all its original contents and furnishings. Visitors can see the 'little nest' as Roald Dahl called it, exactly as he had it set up, with all the extraordinary and fascinating objects he kept at hand for contemplation and inspiration."

Cookbook ghostwriters.

And the fallout.

"The man was sitting on the porch with some people he had just met, talking about books and authors. The 34-year-old man was then approached by another party guest, who started speaking to him in a condescending manner. An argument ensued and the man was suddenly struck in the side of the head, suffering a cut to his left ear, Bush said. The man's glasses went flying off of his head and fell to the ground, with one of the lenses popping out of the frames, Bush said."

Book nerds v. Kanye. NSFW.

Hocus Pocus

Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle.

The Karpeles Manuscript Museum in Charleston is housed in an old Methodist church, a grandly columned Greek Revival building with a rusty front gate and a pipe organ still intact in the back. It's home to a revolving series of manuscripts culled from the private collection of real-estate magnates David and Marsh Karpeles, a couple with very eclectic and expensive taste in papers: in any given season the glass cases wedged around the pews and pulpit contain anything from pages of Roget's original thesaurus to Sir Ernest Shackleton's sketched map of the Antarctic. The February afternoon I visited, a gregarious man with a low-country accent and a flair for displaying pamphlets announced the winter exhibit with pride: "The letters of Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini, an odd pair if ever there was one."

The dozen or so letters and scraps of free-written scrawl were from Conan Doyle and Houdini's brief but spectacular relationship, one that was founded on and destroyed by a shared interest in the possibility of contacting people in the afterlife. It began, as friendships often do, with a book exchange. Read More »

March 20, 2012

Two Poets

From 1993 to 1995 I stumbled in two graduate programs, first economics and then religious studies. I was undone by advanced calculus and cultural theory—couldn't handle the rigor of either, the puzzle of value unsolved. The abstract challenges of school were leavened by my job at Quail Ridge Books, an independent store in Raleigh. There, I shelved hardbacks and backlist paperbacks by Baldwin, Banks, Berger, (Amy) Bloom, Boland, Gass, Grumbach, Gurganus, Le Guin, L'Engle, Malamud, McCarthy, Mitchell, Munro, Walker, Wideman, (C.D.) Wright, (Charles) Wright, (Richard) Wright; I managed the magazines and literary journals, worked the cash register, and made friends with the customers.

I met the late Don Adcock there. A jazz flute player and the longtime band director at North Carolina State University, he first heard bebop in 1945 when he stepped off a battleship in San Francisco and wandered into a joint where Howard McGhee was playing. Fifty years later he would walk into the store and instantly identify whichever jazz musicians were playing on the house stereo—Tommy Flanagan, Hank Jones, Al Haig, Dexter Gordon, Zoot Sims, Lee Morgan, Bunny Berigan—and he knew all the songs, too. He often visited the store with his wife, the poet Betty Adcock, who taught at the local Meredith College as well as at Warren Wilson. Don and Betty became critical sources of encouragement for me as my writing developed, and I spent many afternoons at their Raleigh home—a modern, postwar structure with a flat roof surrounded by heavy woods.

Read More »Robert Silvers on the Paris and New York 'Reviews'

Robert Silvers and Barbara Epstein in the first offices of The New York Review of Books.

This year at our spring Revel, The Paris Review will award its highest honor, the Hadada Prize, to Robert Silvers. Although Bob is now known as a founding editor of The New York Review of Books, from 1954 to 1956 he worked under George Plimpton as an editor at The Paris Review. A few months ago, in conversation with Mark Gevisser at Shakespeare & Co., Bob reminisced about the early days of the magazine. —Lorin Stein

First, welcome, Bob. It's great to have you. You've been here before, in a very different capacity.

Well, when I first went to work for The Paris Review, in 1954, one of my tasks was simply to carry around The Paris Review to the various bookshops in Paris that might accept it or sell it, and I walked in here, and there was George Whitman, on a cold night. He displayed the Review right in front, so that made me feel I was getting somewhere in my rather beginning career.

What was the bookshop like in the fifties?

You would come in here and you would bump into all sorts of people who were writers living here or passing through. At that time there were quite a few writers living in Paris and coming through Paris—Terry Southern, Peter Matthiessen, Donald Windham. And of course, there was our Paris Review group, and there was a group of the magazine Merlin, which was very important, and a rather radical paper, edited by Alex Trocchi, who was one of the few people I've known who was an ardent drug addict. That is to say, he thought it was a marvelous thing to be a heroin addict, but he was a brilliant editor and a brilliant writer. We were all friends. We didn't feel competition too much. Read More »

March 19, 2012

The Regulars

Detail from the Von exhibition poster.

It's not immediately clear that there's an art show happening at Von. The Bleecker Street wine bar always has art up, often the work of Charles von Herrlich, the bar's owner. If anything, the pieces now hanging seem more eclectic, less unified, than usual. There are photo collages, street art, and a shattered mirror pressed into a rounded ceramic cone. There are no titles or names. The most obvious clue that there's a show on is a handwritten sign saying that it continues downstairs.

"The guiding logic was that I know everyone in the show personally," explains Emil Memon, the genial Slovenian expat who curated the show. On the Sunday night before the show—or the Monday morning, he corrects himself—he was "swept up in the big craziness of the Armory and wanted to do something more independent, more democratic." He immediately e-mailed, texted, and called dozens of artists asking for pieces—and Charles, asking whether he could use the bar. He put the exhibition together in four days. "It wouldn't have been possible even two years ago, without the smartphone and Facebook."

Emil talks a lot about how technology helped him get the show together, but as he talks it becomes clear that he built his social network the old way: by hanging out in galleries and East Village bars and by being very enthusiastic about everything everyone is doing. When I ask people how they know Emil, most say "from around" with a look that says, How could you not.

An example of what around can mean. Andrew Strasser, who has an ominously lit video downstairs of himself getting hosed with Diet Coke, met Emil late one night at Vaselka while they were waiting for their checks. Later he brought Emil along as muscle in a job interview with Santos Party House. "I thought it'd help to make them wonder who this weird old guy standing there was." Andrew says that he found out he was in the show when he saw his name on the flyer.Read More »

Something for Nothing

America, from its Puritan past to its mass-incarceration present, has never been particularly hospitable to criminals. Yet, from time to time, an outlaw rises to the level of folk hero, based on a captivating personal narrative or a prevailing mood in the culture. Perhaps no category of crook has been more consistently compelling than the con artist. During their heyday, from the mid-nineteenth century up through the first decades of the twentieth, when innovations in transportation brought more strangers together and promises of fast fortune spread across the country, practitioners earned memorable nicknames—Soapy Smith, Snitzer the Kid, Appetite Bill—and spoke in a florid and amusing argot. (Every object in the game, from money to cards to actors, was given a nickname, as were the games themselves, dubbed the wipe, the wire, the big mitt, the huge duke, the tip, the tale, the strap, the spud, or the shake with the button.) Con men normally stole by guile rather than by physical intimidation or brute force. And their thieving relied on complicated mechanisms of performance and intelligence—it was indeed an art, complete with its own hierarchy of ability. The best of them could be imagined as dashing and debonair—like Paul Newman and Robert Redford in The Sting, men who valued the game more than what it earned.

Most important, the nature of the con implicated the victim in its own criminal logic. Marks were roped in with promises of inside information on a fixed horse race, rigged stock market, or some other path to easy money—only to see their contributions to the dubious venture stolen right before their eyes. As the linguist David Maurer wrote in The Big Con, his encyclopedic study of confidence crimes and the men that ran them, the operation worked based on a fixed maxim: "You can't cheat an honest man."

For many con artists, this was as much an excuse as a credo. Take, for example, the Chicago con man Joseph "Yellow Kid" Weil, who claimed to have stolen more than eight million dollars from assorted marks, as victims in the con game are known, during a career that spanned more than half a century. You would think he'd be the last person inclined to judge harshly the avarice of his fellow man. Yet, in 1956, after he'd turned eighty, he explained himself to Saul Bellow, who summed up the man's conception of the moral universe:

The years have not softened his heart toward the victims of his confidence schemes. Of course he was a crook, but the "marks" whom he and his associates trimmed were not honest men. "I have never cheated any honest men," he says, "only rascals. They may have been respectable but they were never any good." And this is how he sums the matter up: "They wanted something for nothing. I gave them nothing for something." He says it clearly and sternly; he is not a pitying man. To be sure, he wants to justify his crimes, but quite apart from this he believes that honest men do not exist.

While many con artists gained larger-than-life reputations, their victims mostly remained faceless, since, as Amy Reading explains in her engrossing new book, The Mark Inside, most were reluctant to take a complaint to the authorities. Local police were often paid off to look the other way, but even if they hadn't been, marks were unlikely to confess to being robbed while putting money on a crooked scheme. Even the truly innocent—and indeed there were honest and decent people cleaned in cons—wouldn't be eager to come forward and announce their gullibility to the world.

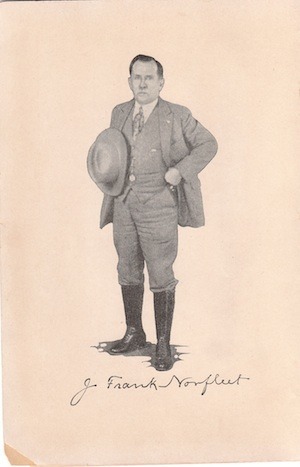

Who, then, would stand up for the victims, the marks who were considered at best fools, or at worst, criminals themselves? Enter J. Frank Norfleet, a short, mustachioed cattle rancher from the Texas panhandle, who became the most renowned advocate for the victims of cons in the history of the game. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers