The Paris Review's Blog, page 928

March 16, 2012

Reading On the Road; Fiction for a Father-in-law

My father-in-law, a fiercely intelligent Irishman in his late sixties, has just been diagnosed with cancer. As he is facing a long period of being confined to quarters, I'd like to send him some books to help pass the time. However, he has candidly admitted to me that his concentration is not what it once was, and he finds reading anything of extended length quite difficult. Would you have any suggestions—collections of short pieces of fiction, or tales, personal essays, travel memoirs, for example—that might be suitable? When he's feeling like his usual self, he enjoys reading Brian Moore and John Banville, outsmarting Stephen Fry on reruns of Qi, and finishing the Irish Times cryptic crossword in half the time it takes me to struggle through the Simplex.

My father-in-law, a fiercely intelligent Irishman in his late sixties, has just been diagnosed with cancer. As he is facing a long period of being confined to quarters, I'd like to send him some books to help pass the time. However, he has candidly admitted to me that his concentration is not what it once was, and he finds reading anything of extended length quite difficult. Would you have any suggestions—collections of short pieces of fiction, or tales, personal essays, travel memoirs, for example—that might be suitable? When he's feeling like his usual self, he enjoys reading Brian Moore and John Banville, outsmarting Stephen Fry on reruns of Qi, and finishing the Irish Times cryptic crossword in half the time it takes me to struggle through the Simplex.

With thanks,

amrh

Your father-in-law sounds great. You might ask whether he's read Brian Moore's novella Catholics. It's a very short read, recently back in print: he may have missed it the first time. It happens to have been a favorite of David Foster Wallace; from your description, I wonder if your father-in-law might enjoy Wallace's essays (either A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again or Consider the Lobster) or my colleague John Jeremiah Sullivan's Pulphead. (Read his recent essay on Ireland if you'd like a preview.) Or Geoff Dyer's essays, as for example Yoga for People Who Can't Be Bothered to Do It. These are all witty essayists I read when my attention flickers low. Along the same lines, Sadie suggests Clive James's Cultural Amnesia and Malachy McCourt's very breezy but entertaining memoir A Monk Swimming.

Does your father-in-law have any interest in Russia? For sheer storytelling, I recommend Ken Kalfus's PU-239 and Other Russian Fantasies or any collection by Alice Munro (I won't bother recommending William Trevor). You mention tales; it's an obvious one, but I've found Isak Dinesen's Seven Gothic Tales good sickbed reading. For travel writing, maybe Richard Holmes's Footsteps or Robert Louis Stevenson's Travels With a Donkey in the Cevennes?

We wish him a speedy recovery!

I'm looking for a couple of good books—novels or short stories—to read aloud with my boyfriend as we drive from Arizona up through the Badlands to a new start in New York. (We are not—not quite—as young and idealistic as that sentence makes us sound.) What would you recommend?

We like your style.

I suggest you keep a few books going at once, so you can switch around according to the driver's—and the reader's—mood. Thus, in no particular order, My Antonia, Denis Johnson's Angels, True Grit, Last Evenings On Earth, American Purgatorio, any of Patricia Highsmith's Ripley novels, and The White Hotel. All have a good strong voice, requiring no acrobatics on the reader's part, most have something to do with travel, and all of them clip along. Sadie points out that the Victorians tend to be good for reading aloud—maybe the Palliser series?—and suggests the stories in Daphne du Maurier's Don't Look Now. (She also proposed Another Roadside Attraction—and collapsed in giggles, for reasons best known to herself.) Read More »

Staff Picks: Sexual Humiliation, Advanced Style

"No one wants to be called a penis with a thesaurus. For an English-language novelist, raised and educated and self-consciously steeped in the tradition of the Anglo-American novel, in which female characters, female writers, and female readers have had a huge part, the prospect of not being able to write for female readers is a crisis. What kind of novelist are you if women aren't reading your books?" Elaine Blair on DFW, sexual humiliation, and that obscure object of desire, the woman reader. —Lorin Stein

"No one wants to be called a penis with a thesaurus. For an English-language novelist, raised and educated and self-consciously steeped in the tradition of the Anglo-American novel, in which female characters, female writers, and female readers have had a huge part, the prospect of not being able to write for female readers is a crisis. What kind of novelist are you if women aren't reading your books?" Elaine Blair on DFW, sexual humiliation, and that obscure object of desire, the woman reader. —Lorin Stein

I've been reading and rereading galleys of The Poetry of Kabbalah, an anthology of Jewish mystical verse translated (and massively annotated) by Peter Cole. This is ambitious poetry. It combines liturgical solemnity with outrageous flights of metaphor, and Cole's versions match the originals step for step. About the Poems of the Palaces, a series of hymns from the first millennium, Cole writes that it is "a poetry written for men who would become like angels, serving and praising God. It is not a poetry of 'personal voice' or 'a meter-making argument' with a 'self.' Rather, it is a verse rooted in the magical power of letters and words." —Robyn Creswell

I was so excited when Ari Seth Cohen's Advanced Style landed on my desk—my love of the blog is no secret and being able to peruse these grandes dames at my leisure is even better! —Sadie Stein

Here's an example of why some people need actual bookstores: if I hadn't seen it sitting there at the Strand, I'd never have picked up Babbitt—and what could be better for a bad mood on a Saturday night with a cold? —L. S.

If you are like me and springtime puts you in a whimsical, dancing mood, try The Band Wagon with Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse. Though I am too timid (and clumsy!) to dance like that myself, I live vicariously through their twirls and sashays through Central Park. —Elizabeth Nelson

The huge, knotted automobile parts now on view in the John Chamberlain retrospective at the Guggenheim each look like brushstrokes made massive, three-dimensional, and wonderfully kinetic. —Deirdre Foley-Mendelssohn

The Wilder Quarterly is the perfect thing to read in these early days of spring: the Brooklyn-based magazine is a stylish paen to all things green and growing and donates part of proceeds to the Fresh Air Fund. —S. S.

March 15, 2012

"Boy's Room"

George Oppen.

"It is possible," George Oppen wrote, in early 1962, "to find a metaphor for anything, an analogue: but the image is encountered, not found; it is an account of the poet's perception, the act of perception; it is a test of sincerity, a test of conviction, the rare poetic quality of truthfulness." "Boy's Room," which is about just such a perceptual encounter, and truthful almost to a fault, appears in Oppen's 1965 collection, This in Which, his second after a silence of more than twenty-five years. Between Discrete Series (1934) and The Materials (1962), Oppen raised a daughter; he worked as a carpenter; he joined, then became disillusioned with, the Communist party; he lived in Mexico; he fought in World War II (not necessarily in that order). What he did not do, for the most part, is write. When he returned to poetry in 1958 it was with a vigor that "Boy's Room" amply demonstrates. The collection that followed, Of Being Numerous (1968), would win him the Pulitzer Prize. He died in 1984, and though the details of his personal life are salacious enough—an affluent childhood, his mother's suicide; a car accident in which his passenger was killed, a first date that led to his future wife's expulsion from college (they stayed out all night and she missed her curfew)—he is largely forgotten. It's a real pity. "No ideas but in things" is a line from a William Carlos Williams poem, but Oppen's work fits the bill as well as Williams's does.

I can remember the first time I read "Boy's Room" because of the physical sensation that accompanied it: I felt like I was falling. The drop occurs in the gulf between the first and second stanza: "A friend saw the rooms / of Keats and Shelley / At the lake, and saw 'they were just / Boy's rooms' and was moved // By that." I, too, was moved by that.

Of course, the friend is right in a purely literal sense: Keats died at twenty-five, Shelley at twenty-nine. Confronted with their actual rooms, there's a sense of surprise and sympathetic feeling: these towering figures of romantic poetry were not only real people, they were youngsters who had not quite outgrown their adolescence. But from the discrete thing—the rooms of Keats and Shelley—comes the broader idea: "indeed a poet's room / Is a boy's room." Such a sheepish admission for the poet to make, to indict himself. Read More »

A Routine Matter

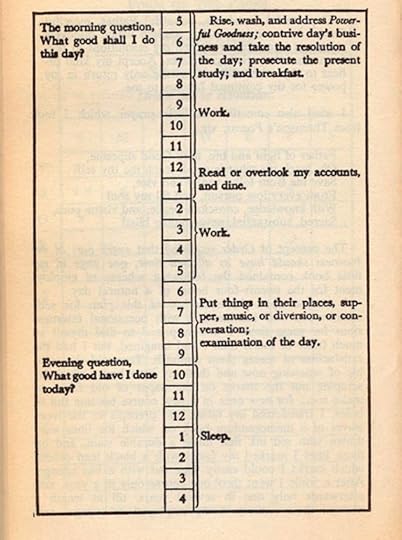

Benjamin Franklin's daily schedule.

I recently turned thirty, the age by which, according to William James, "the character has set like plaster, and will never soften again." But he wrote that in 1890, before mobile devices and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and Lana Del Rey and the fragmentation of the self, and I'm happy to report that my character is as soft as unhandled Play-Doh. For the past year I've slept mostly in well-worn twin beds generously provided by writing colonies, my life a new kind of nomadism made possible by America's patrons of the arts. Every morning I get up at seven, or seven thirty, or eight, or eleven, and record my dreams, or forget them, then make my bed, or not, after which I proceed immediately to take a shower, or start the coffee, or eat breakfast, or go for a walk, then sit down at my desk to begin the day's work, or write e-mails, or stare out the window, or do absolutely anything else. I usually end my day by reading a book, or talking on the phone, or watching basketball highlights on ESPN.com, or wondering why I keep the channel on Jimmy Fallon when every instance of empty enthusiasm makes me loathe him a little more.

William James again: "There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation. Full half the time of such a man goes to the deciding, or regretting, of matters which ought to be so ingrained in him as practically not to exist for his consciousness at all. If there be such daily duties not yet ingrained in any one of my readers, let him begin this very hour to set the matter right." This very hour.

Habits are for squares, is what I've always felt. Read More »

March 14, 2012

On the Shelf

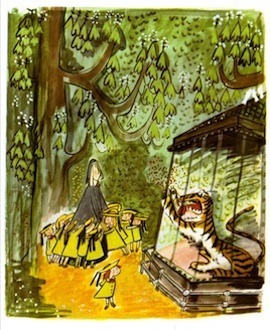

Madeline.

A cultural news roundup.

RIP, Encyclopedia Britannica.

A Delhi conference was too small for both Salman Rushdie and Pakistani cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan.

Southampton's venerable "" is being sued by the upcoming film; Stephen Fry leaps to its defense.

Das Rheingold? There's an app for that.

I'll be dipped! A dictionary of regional American English.

Gilgamesh! The Urban Dictionary lit guide.

What we talk about when we talk about fan fic.

Good Books, indeed.

Hemingway's keeper shelf.

Build your own Murakami!

Discovered: five hundred forgotten fairy tales.

Madeline 's mixtape.

Hitchens reports on the afterlife.

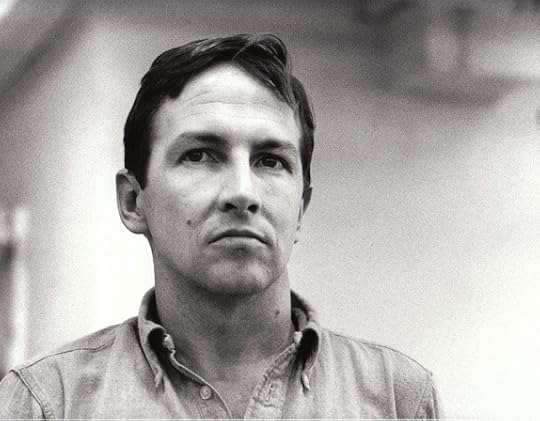

Salter's Armory

James Salter, Robert Rauschenberg, 1963, black-and-white photograph, 16 x 20 inches.

If you are neither looking to buy art nor quite understand the glut of it before you, what do you do at the Armory Show? To an ill-informed visitor, it's like being at the Louvre, but without the benefit of history to fall back on. The show's aesthetic labyrinth is thus the source of a certain amount of bafflement. I dealt with this quandary partly by writing down what it was I happened to see and enjoy, as though to come back to it later: Ai Weiwei's porcelain owl houses; some distorted nudes by the photographer André Kevesz; a series of vegetables in gelatin-silver prints by Charles Jones; the Turkish artist Irfan Onurmen's tulle portraits; totem poles by Charlie Roberts; a photograph, called L'Oiseau dans l'Espace, by Brancusi.

I arrived late on the last day of the show and spent the first twenty minutes of my visit searching for the press office (ah, the other pier), explaining why I did not possess any sort of business card, failing to locate the down escalator and descending alone in an elevator twice the size of my kitchen. I eavesdropped on a couple trying to decide if they could afford two seventeen-thounsand-dollar Weegee prints, agreeing they had space in their home. Then a young man told his friend just how badly he wanted to fuck someone's sister ("so bad"). Next to the champagne bar, beneath a huge neon sign reading scandinavian pain, I allowed a kind Norwegian to apply a temporary tattoo to the underside of my wrist with a damp paper towel. I was surprised at how intimate this was—he might have been taking my pulse.

"You see," he said, "most of what this is about is the fact of making it happen at all."

Almost by chance I found the booth for "As They Were: American Masters Through the Lens of James Salter," a combined effort by Loretta Howard and Nyehaus galleries, showcasing some of James Salter's films and photographs taken between 1962 and '63 while he had a studio in Peek Slip. In the event you don't know who Salter is, the curators have obliged by providing a few old editions of his books in a glass case, along with the script for his film Downhill next to a bluish spiral of canistered film sitting atop the receipts from its printers. There is a photo of the bearded Salter, standing behind his camera in a field, and another of the author as an old man, being greeted by Robert Redford. So, you see: legit. Read More »

March 13, 2012

Amie Barrodale Wins Plimpton Prize; Adam Wilson Wins Terry Southern Prize for Humor

Amie Barrodale.

On Tuesday, April 3, The Paris Review will honor two of our favorite young writers.

Amie Barrodale will receive the Review's Plimpton Prize for "Wiliam Wei," which appeared in our Summer issue.

Adam Wilson will receive the second Terry Southern Prize for Humor for his story "What's Important Is Feeling" and his contributions to The Paris Review Daily.

The Plimpton Prize for Fiction is a $10,000 award given to a new voice published in The Paris Review. The prize is named for the Review's longtime editor George Plimpton and reflects his commitment to discovering new writers of exceptional merit. The winner is chosen by the Board of the Review. This year's prize will be presented by Mona Simpson.

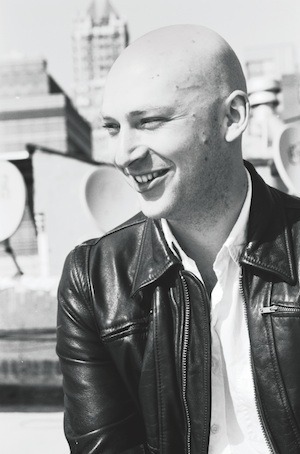

Adam Wilson.

The Terry Southern Prize for Humor is a $5,000 award recognizing wit, panache, and sprezzatura in work published by The Paris Review or online by the Daily. Perhaps best known as the screenwriter behind Dr. Strangelove and Easy Rider—and the subject of an interview in issue 200!—Terry Southern was also a satirical novelist, a pioneering New Journalist, and a driving force behind the early Paris Review. Comedian David Cross will present this year's award.

The honoree of this year's Revel is Robert Silvers. Zadie Smith will present Silvers with the 2012 Hadada, the Review's lifetime achievement award recognizing a "strong and unique contribution to literature." Previous recipients of the Hadada include James Salter, John Ashbery, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Peter Matthiessen, George Plimpton (posthumously), Barney Rosset, Philip Roth, and William Styron.

Come help us celebrate our honorees and our two hundredth issue—and support the Review. Buy your Revel tickets now!

Susanne Kippenberger on 'Kippenberger'

Martin Kippenberger in Venice, 1996.

In 1997, when Martin Kippenberger died of alchohol-related liver cancer at the age of forty-four, Roberta Smith opened her New York Times obituary by writing that Kippenberger was "widely considered one of the most talented German artists of his generation." In fact, outside of a subset of fellow Conceptual artists and prescient gallerists, he was not considered at all. At the time of his death, a museumgoer might have recognized a blurred Richter or a grim Joseph Beuys while being totally unfamiliar with Kippenberger's hotel drawings, the now-famous series of doodles on hotel stationary.

Kippenberger's reputation has slowly cemented since. He has been the subject of an extensive 2006 Tate Modern show, a U.S. exhibition that came to MoMA in 2009, and now a biography, released by J&L Books. Kippenberger: The Artist and His Families is written by Susanne Kippenberger, the artist's youngest sister and a journalist at the Berlin daily Der Taggespiegel, and translated from German by Damion Searls. It is both a profile of a mad art star and a fascinating history of the bohemian scene in Germany before the fall of the wall. When Ms. Kippenberger met me at City Bakery recently to discuss the book, she did not, as her brother might have, jump on top of the table and pull her pants down, before forcing me to stay out all night drinking.

I saw the Tate show in 2006 and left astounded by the incredible amount and range of work created by someone who died so young. The retrospective included the massive installation "The Happy End of Franz Kafka's 'America'," which is an ersatz sports field filled with desks and chairs; the ironic self-promotional exhibition posters; punkish figurative paintings; self-authored catalogues; and sculptures. I was surprised to find, reading your book, that when he was alive his art seemed eclipsed by his renown as a personality.

Yeah, people thought, He doesn't do anything. He just sits in bars, throws parties, and talks and drinks and puts on a show of himself. Read More »

March 12, 2012

314 Bedford

"Love amid apocalyptic urban debris, love amid pimps and drug pushers, love on staircases scattered with used needles … can barely pay the rent." This was not an atypical note to find myself jotting down in my early twenties, part of a scribbled, half-legible foray into a novel I would never write. I wrote this in 2002, three years into my very first no-lease, single-occupant New York apartment and one year before I would eventually leave it, fleeing on grounds of emotional distress for a nondescript studio in Gramercy across from the Thirteenth Precinct (note my subconscious need for police protection). The cloying repetition of the word love suggests a rather flagrant tendency toward romanticizing crime and poverty, the ellipses symptomatic of someone too undisciplined to develop a thought. The only real character of this imaginary novel is the building. At least it was for me during the years that I called 314 Bedford Avenue, between South First and South Second streets on the grimy, sun-bleached south side of Williamsburg, my home.

To pass by the six-floor tenement now is not to see the building I lived in a decade ago. DuMont Burger has replaced the Puerto Rican dry cleaners in the street-level store front, where I never recall a single person entering or exiting with pressed shirts or anything approximating a claim ticket. Green metal café tables have taken the place of the wheelchair-bound homeless man with no legs who lived and slept seated for nine months of the year outside the entryway, his single mode of communication being "don't touch me!" whenever anyone asked if he needed help. The building's facade, still the color of a sick tongue, seems to have been water blasted, and the fire escape has been skinned and painted. As New Yorkers, we all live in a peculiar state of location upgrade, a kind of reverse Manderlay, where places we had once known have outpaced our own internal soft-focus (as an exercise, I recommend replacing the word nature with real estate developers in the opening page of Rebecca). Memory must do the decay work of time, and it is here at 314 that I remember the black, rusted iron gates of the front door, the hallway swabbed in yellow plaster, the chipped linoleum floor tiles attempting a marble mosaic, the five flights up to my apartment where, even drunk at 2 A.M., I had to be careful not to step on syringes, used condoms, sleeping prostitutes, and take-out ketchup packets. Read More »

A Tote for 200!

Our 200th Issue tote!

We are thrilled to offer you what may be the coolest tote bag in Paris Review history! When you renew or subscribe to The Paris Review, you'll receive this 11'' x 13'' eco-canvas tote, which takes its design from the cover of our two-hundredth issue (itself an adaptation of our very first cover, in 1953). And, as if it needs saying, a full year of fiction, poetry, interviews, and essays. All for $40.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers