The Paris Review's Blog, page 926

March 28, 2012

Dear Don Draper, It's a Wonderful Life

Dear Don Draper,

Birthday greetings from the year 2012! Adam Wilson here, writing to tell you that things will be okay!

I know life looks bleak right now, Don. You just turned forty. You're feeling it. Your frown lines tell the tale, your smoke-seasoned cheek skin, the whiskey jaundice blooming in your beautiful eyes. The way your manly body slumps and crumples, finally flaccid after decades of tumescence.

It's 1966 and everything's orange and yellow, plush and furry, groovy, heady, already psychedelically aglow. At the end of last season you were smiling like a lobotomized monkey, gaga over Megan the secretarial sex machine, offering love and financial security in exchange for a peek at her abs.

Now you've got the spoils of that horny dream and it's not a pretty sight: an open plan apartment accented by white rugs and cream-colored decorative pillows; a wife whose sexual liberation extends outside your bedroom and into the public salon where she'll embarrass you in front of your coworkers, strutting her silky stuff while a band of blond surf bros play anesthetized hippie pop; daughter Sally quickly turning Lolita; your son Bobby all but unrecognizable from last year (it's not your fault—they changed the actor); baby Gene with his creepy, beady eyes; plus the possibility of even more unwanted children! Read More »

On the Shelf: Thurber Insults and Library Dreams

Happy seventy-sixth, Mario Vargas Llosa!

Muggles get the Harry Potter treatment in Florida. "At Ollivanders, the wand shop, character actors put on a show. With a few dozen people crowded into a room, a bearded wizard proceeds to help a child select a wand. 'Descendo!' he cries. Boxes tumble down and the shelves fall apart on cue. It was the wrong wand. 'Repairo!' he cries. The shelves put themselves back together. The long-bearded gent eventually gives the girl an Ash wand, 'an excellent wand for a charismatic, successful wizard.'"

You can even read the books!

At forty-two, historical novelist Rabee Jaber is the youngest winner of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction.

On the plus side, James Thurber wrote back to his fans. "One of the things that discourage us writers is the fact that 90 per cent of you children write wholly, or partly, illiterate letters, carelessly typed. You yourself write 'clarr' for 'class' and that's a honey, Robert, since s is next to a, and r is on the line above."

An ode to the thesaurus.

How about a little fancy-library porn? (This Johns Hopkins professor totally beats Lagerfeld in the library stakes.)

Book origami.

Henry James is the most-studied writer.

Did it really take this long to make an Art of War graphic novel?

The Grandmaster Hoax

In September 2006, the World Chess Championship devolved into a debate about bathrooms. One champion, Veselin Topalov, accused the other, Vladimir Kramnik, of excessive urination, hinting that Kramnik was retreating to the unmonitored bathroom to receive smuggled computer assistance. (Kramnik responded that he merely drank a lot of water.) Kramnik was eventually declared the victor, but to many, the episode displayed the sad state that the grand game had fallen into since Garry Kasparov lost to IBM's Deep Blue in 1997. Back then, Kasparov was bitter about the loss and accused IBM of cheating—with human intervention, saying that he saw uncanny human intelligence in the computer's moves.

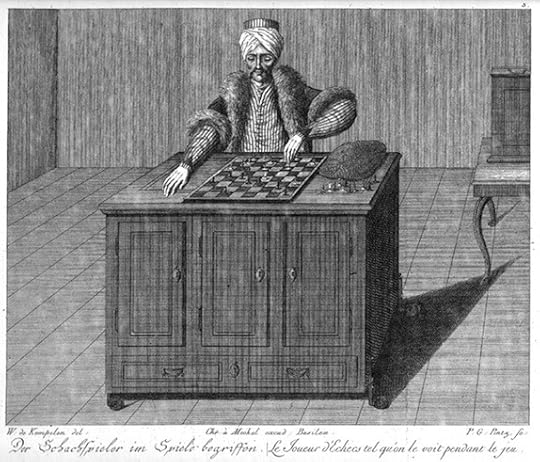

Even that incident, though, was not the first time the line between man and machine had been blurred in the game. The first machine to awe humanity with its chess mastery was the eighteenth-century life-size automaton known as the Turk. Constructed in 1770 by Wolfgang von Kempelen to impress Empress Maria Theresa, the Turk appeared as a wooden Oriental sorcerer seated at a large cabinet. Before playing commenced, Kempelen would open the cabinet doors to reveal the clockwork machinery that controlled the Turk. The audience could see that there was nothing else inside. After the doors were closed and a challenger seated, the Turk would come eerily to life. He would move the pieces robotically, but shake his head or tap his hand in human displays of annoyance or pride. He also nearly always won.

The Turk became a spectacular attraction, thrilling, baffling, and terrifying viewers across Europe and America for decades. Read More »

March 27, 2012

On Tour with The Magnetic Fields: Part I

I've worked for the band the Magnetic Fields for the past ten years and have sold their merchandise on every tour since they released i, in 2004. Their latest tour, for their new record, Love at the Bottom of the Sea, began last week, and, as is my wont, I've been taking notes. After a warm and fuzzy show in Hudson, New York, the first completely positive experience in Philadelphia in recent memory, and a very quick trip to Minehead, England, for All Tomorrow's Parties, the Magnetic Fields took the Tour at the Bottom of the Sea to Austin, Texas, for their first-ever appearance at South by Southwest, the juggernaut music festival that turns the entire city into a beer-and-taco-stained pair of jeggings. Half the band and crew flew in from New York, and the other half from Boston, meeting up in the Dallas-Fort Worth airport for the puddle jumper to Austin. We shared the plane with several members of the E Street Band, which made Sam Davol (cello) quiver with excitement. When we landed, the steamy Texas air relaxing our synapses, Sam asked E Street violinist Soozie Tyrell for her autograph, and I made a proclamation: in Austin, I was going to find a) Bruce Springsteen or b) Timmy Riggins, my very favorite fictional character on Friday Night Lights, played by heartthrob and Austin resident Taylor Kitsch. I find that wishes are more likely to come true when spoken aloud. Read More »

Michael Robbins on 'Alien vs. Predator'

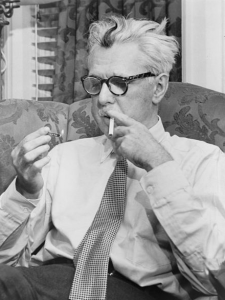

Michael Robbins.

Reading the poetry of Michael Robbins is kind of like driving around the parkways and frontage roads of America's suburbs. His poems have a Best Buy, a Red Lobster, a Kinko's, a Pizza Hut, and a Guitar Center; they reference the slogans of Christian billboards and the bumper stickers of hippies; they offer the choice between Safeway and Whole Foods and between the corporate classic-rock station, the corporate urban-music station, and All Things Considered. The poems are heavy with concern for the elephants, the whales, and the freedom of Tibet. They have a Rhianna song stuck in their heads.

Among poets, Robbins follows in the footsteps of Frederick Seidel and Paul Muldoon in writing about contemporary life using more traditional poetic forms and rhyme. He also references and sometimes even quotes Philip Larkin, John Berryman, Theodore Roethke, Wordsworth, and others. But Robbins is more playful and less grandiloquent than his sometimes-grim forefathers: after reading his first book, Alien vs. Predator , the two things I kept thinking of were not poetry at all, but rather the short stories of George Saunders and the video art of Ryan Trecartin. As Saunders did with marketing jargon and Trecartin with reality television, Robbins congeals his suburban idyll, transforming its vacant vernacular into unsettling poignancy. And sometimes it's even funny.

I reached Robbins by phone in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. We spoke the day after Rick Santorum's victory in that state's Republican primary.

Where are you working right now?

I'm a visiting poet at the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg, which is where I'm staying and just waiting until I get out of this city.

You don't like it?

The people are great at the university, my students are great, but Hattiesburg is … it's just like if you opened a university in a Taco Bell, basically. It's just the ugliest place I've ever seen in my life. Read More »

Adieu, Deirdre; Bienvenue, Sadie

Sadie Stein.

Faithful readers, we have good news and bad news.

The bad news is that our senior editor, Deirdre Foley-Mendelssohn, is ditching us for Harper's magazine. It is a grievous blow. During Deirdre's tenure as editor of the Daily, our readership has doubled and so has the amount we publish. Truly we have grown by leaps and bounds. At Harper's, Deirdre will oversee the book section—one of the best in the country—so our loss is America's gain. That, anyway, is our line, and we're sticking to it.

The good news is that our deputy editor, Sadie Stein, has bravely agreed to step into Deirdre's seven-league boots. You already know Sadie from her groundbreaking reports on wine cake and exotic meats and "the old 'do I give my crush a sexually explicit book' conundrum," not to mention her weekly roundup, On the Shelf. We trust that you will welcome her in her new capacity—effective April 1—and join us in wishing her luck!

March 26, 2012

Get Your Paris Review Totes While They Last!

If you're just joining us, a recap: when you buy or renew a Paris Review subscription, you'll receive this lovely tote bag, inspired by our Spring cover, all for $40.* Not to mention, four issues of the best fiction, essays, poetry, and interviews.

But act fast! This offer expires Wednesday, March 28, at 6 P.M. Paris Review time (which is, confusingly, also Eastern Standard time).

In short: order now!

And don't forget your Revel ticket—you only have until the end of the week to reserve a spot at the best party in town.

*Canadian and international prices are higher.

Our Twilight Lands

Argentinian journalist Leila Guerriero wrote this article, translated by Sarah Foster, based on her interview with Chilean poet Nicanor Parra at his home on the coast of Chile. It was published in the Spanish newspaper El País after Parra was awarded the Cervantes Prize last December. The prize, given by Spain's Ministry of Culture, is the most prestigious literary award in the Spanish-speaking world. Parra's poem "Defense of Violeta Parra" appeared in our two-hundredth issue, on newsstands now.

Reaching the house where Nicanor Parra lives, on Lincoln Street in Las Cruces, a coastal town two hundred kilometers from Santiago de Chile, is easy. The hard part is reaching him.

Nicanor Parra Oiundo de San Fabian de Alico is the first-born son out of a total of eight children brought into the world by Nicanor Parra, a high school teacher, and Clara Sandoval. He was born in 1914, was twenty-five during World War II, sixty-six when John Lennon was shot, and eighty-seven when the planes hit the towers. Last September, he turned ninety-seven. Some people don't even know he's still alive.

Las Cruces is a town with two thousand inhabitants, shielded from the Pacific Ocean by a bay that embraces several towns: Cartagena, El Tabo. Parra's house is on a cliff, overlooking the sea. In the garden, a staircase comes down to the front door, where local punks have painted graffiti so that no one will dare touch the house; it says, "Antipoetry." In the foyer, he has written the names and telephone numbers of his children.

Nicanor Parra's hair is white. He has a long beard and no wrinkles, only furrows in a face that seems to be made of earth. His hands are tanned, no spots or creases, like two roots rinsed in water. Lying on a table is the second volume of his complete works, Obras completas y algo (1975–2006). In its preface, Harold Bloom writes, "I firmly believe that, if the most powerful poet produced by the New World until now is still Walt Whitman, Parra joins him as an essential poet in our Twilight Lands." At the end of the eighties, when Parra was still living in Santiago, he stopped giving interviews, and, although there have always been exceptions, he often objects to direct questions in unexpected ways, so that a conversation with him is subject to uncertain diversions, into topics that he repeats and brings up for whatever reason: his grandchildren, the Laws of Manu, the Tao Te Ching, Neruda. Read More »

Death in the Afternoon

On the fifteenth of June 2008, only a few minutes after stepping into the sand of Madrid's bullring, the bullfighter José Tomás was covered in blood. Just ten days before, he had had his most glorious fight ever, a fight that turned even the usually skeptical aficionados ecstatic. That second afternoon the stakes were high, but the bullfight proved to be crude and epic. Tomás was gored three times. After each goring, he stubbornly stood up, planted himself on the ground, and fought on, never stepping back from the bull. His torso bent achingly slowly, inches from the animal, to subtly guide the charge. His calm was astounding. It didn't matter that this time the bulls weren't following his wrist but rather searching for his body—he wanted to deliver the same smooth performance as he had ten days before.

Tomás had to undergo three operations as soon as he left the ring. One of the wounds ran twenty inches into his right thigh and tore his muscle. Some viewers accused him of being suicidal; others saw the consummate performance of Spain's best bullfighter, one who was ready to fight steadily till the end. When a journalist asked the old former matador Esplá, "What is courage?" he answered, "It's the spot where José Tomás stands."Read More »

March 23, 2012

After-College Angst; Getting Undepressed

This week our friend Sasha Frere-Jones was kind enough to share his good counsel. By day, Sasha is the pop critic for The New Yorker, and by night he is a member of the bands Calvinist and Piñata. By day or night, he gives darn good advice.

This week our friend Sasha Frere-Jones was kind enough to share his good counsel. By day, Sasha is the pop critic for The New Yorker, and by night he is a member of the bands Calvinist and Piñata. By day or night, he gives darn good advice.

Lately I've been watching a lot of after-college angst films. Kicking and Screaming by Noah Baumbach and St. Elmo's Fire by Joel Schumacher more than any others, though there are others. Anyway, I'm currently studying writing in Chicago, and with graduation just around the corner I've been wondering about novels that focus on this time period, or perhaps even nonfiction. I realize there are many college novels, and books about people who have in fact received diplomas from various universities, but I'm wondering more about books that focus purely on that new onset of confusion immediately after leaving the comforts of academia.

Try Sheila Heti's How Should a Person Be? and Elaine Dundy's The Dud Avocado. Dundy's book is set in 1950s Paris, ground zero for Madcap Hijinks. A young woman named Sally Jay Gorce larks about, alternating between enthusiastic musing and socially inept hedonism. Some of the comedy is too arch, like a Jack Lemmon movie with too much mugging, but Gorce is as likable as Lemmon. Dundy's sentences are rhythmically subtle and easily devoured. It is not a bad thing to be reminded that your postcollege years can be infinitely ill-considered without doing too much damage.

How Should A Person Be? is the inverse of The Dud Avocado. The book's form is fluid and unpredictable: lists are followed by dramatic dialogue, and a fair number of pages are devoted to a competition between friends to see who can create the worst painting. The architecture gives the prose a circular, easy feeling, even though Heti is taking a hard look at what makes life meaningful and how one doesn't end up loveless and lost. It is book peopled by twentysomethings but works easily as a manual for anyone who happens to have run into a spiritual wall. (Heti's book is out in Canada now, but will be released here in June. The American version will be different, because Heti herself wanted to modify the text, a fairly unusual thing in fiction.)

Dear lovely Paris Review,

Could you let me know of a few books, written between 1790 and 1930*, that will make me undepressed? I don't mean a book that's necessarily funny or optimistic, usually those throw me even deeper into depression—I mean something that's going to legitimately make me see the world through someone else's completely fascinating or biased or hyper-judgmental or abstract vision of it so that I can leave my own consciousness for a bit? Or even a book that puts depression into perspective.

Thanks,

Henry

*I add a time constraint because I would like to read books that were written before depression was labeled as such, or diagnosed.

I can't promise that either of these books will cure depression or induce happiness—enormous tasks—but both are fantastic and are narrated by protagonists living in fractured worlds. Emilio Lascano Tegui's On Elegance While Sleeping was published in 1925, and is as far from self-help psychobabble as fiction gets. The protagonist, Meursault, is entirely unreliable, and that is not a failing. He wanders, apparently syphilitic, through a French village at some point in the nineteenth century. He witnesses acts of depravation and plans, in a leisurely way, to commit murder. The book is brief and compressed, with the blurred edges of a dream, and the perversity of the characters is matched by the economy of Tegui's prose. The present moment seems pretty timid after spending time in Meursault's mind.

Fernando Pessoa did not exactly write The Book of Disquiet, which was assembled from various scraps and published long after the author's death in 1935. The fragments that make up this book are attributed to Bernardo Soares, one of Pessoa's several alter egos, or "heteronyms," as he called them. Soares seems almost identical to Pessoa, from what we know, and this work chronicles the life of a flaneur in Lisbon, walking, worrying, assembling, and disassembling his own psyche. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers