The Paris Review's Blog, page 929

March 9, 2012

Campy Fiction; Smoking Strictures

Watching a marathon of Twin Peaks has gotten me thinking about camp. There are movies and television shows that we delight in, and discuss seriously, though the content may not be "serious." What can be said about campy contemporary fiction? Please give me a list of fabulous, outlandish books, preferably with a narrator who will repulse and delight me all at once. Something bad, but well-written.

Watching a marathon of Twin Peaks has gotten me thinking about camp. There are movies and television shows that we delight in, and discuss seriously, though the content may not be "serious." What can be said about campy contemporary fiction? Please give me a list of fabulous, outlandish books, preferably with a narrator who will repulse and delight me all at once. Something bad, but well-written.

Delight may not be the operative word, but David Vann's new novel Dirt is outlandish, repulsive, well-written, and utterly over the top. In one climactic scene, the teenage hero imprisons his mother in a toolshed after she threatens to have him arrested for the statutory rape of his cousin. True to its title, the book is down and dirty. I am not sure whether the camp is intentional—but then I often suspect that many of the best "camp" artists, as for instance Lynch and Almodóvar, do mean it, and that their sincerity is one source of their power.

If you're looking for high camp—without the Sturm und Drang—it doesn't get campier than James McCourt's 1971 send-up of the opera world, Mawdrew Czgowchwz (pronounced "Mardu Gorgeous"). And if soap opera's more your speed, try Cyra McFadden's 1977 The Serial: A Year in the Life of Marin County.

Dear Lorin,

I've recently moved to Manhattan only to learn that I am actually a ghost—that I am, apparently, an apparition. Needless to say, this discovery has been rather disconcerting, but my chief worry is that the recent strictures regarding smoke in apartments and Central Park will cause me rapidly to be evicted from my apartment, and possibly excommunicated from the city outright. I have it from trusted sources that you are at once smoking, wispy, and nebulous—indeed, altostatus cumulus—and yet you seem to face little threat from the law. Lorin, my friend, how do you do it?

Spiritedly,

Spook

Dear Spook,

My secret is I don't smoke very much. It's bad for you! It's probably even bad for ghosts ...

To the wise members of The Paris Review,

The only poem I have ever memorized was for Spanish class in ninth grade. It is time to add to the repertoire, but which poem do I choose? I imagine that it would be a comfort—something inspiring about living, loving, the natural ups and downs of being human. Perhaps something about choices, or appreciation. Not too long or too short. Something to share when the moment is right, or something to keep to myself, to repeat in a chant-like form on long runs through the woods. I maintain full confidence in your advice.

Sincerely,

Julia

Dear Julia,

Once my friend Cary and I had a poem-memorizing contest. He memorized poems by Richard Hugo. I memorized poems by Keats. Each poem had to be longer than fourteen lines, and each of us had to pay the other a dollar for every line we muffed. My favorite of the poems I learned is the "Ode on Melancholy," which I think may fit the bill. At least, I go around repeating it to myself in low moments, and it seems to do the trick. (Note that the word "globed" should be pronounced with two syllables.) Read More »

Staff Picks: Cecil Beaton in the City, 'Threats'

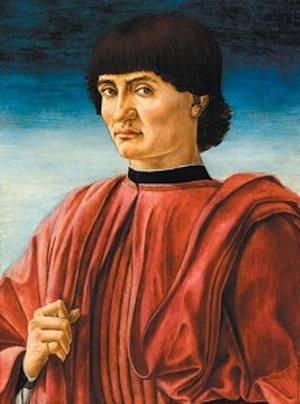

Andrea del Castagno: Portrait of a Man, circa 1450–1457. Courtesy the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

If you get the chance, check out "Cecil Beaton: The New York Years," which has extended its run at the Museum of the City of New York. It's a record of the artist, designer, photographer, and general man-about-town's relationship with the city in pictures and words, and both the duration of Beaton's career and the scope of his creativity are something to behold. —Sadie Stein

On the recommendation of our art editor, Charlotte Strick, I've started reading Amelia Gray's debut novel, Threats—the nifty cover of which Charlotte designed, so perhaps she's biased. But so far, it's with good cause: the narrative is subversive and impressionistic, evidentiary and eccentric. It reminds me occasionally of Grace Krilanovich's The Orange Eats Creeps, another deeply imaginative book and one that, in the spirit of this post, I'd wholly recommend. —Nicole Rudick

It is, as Andrew Butterfield says in The New York Review of Books, a show "of staggering beauty and revelatory importance" and "a landmark exhibition," and it is also your last chance to see it this week. I spent last Sunday strolling through the "The Renaissance Portrait from Donatello to Bellini" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and I can't imagine a more colorful or vibrant way to spend the weekend. —Deirdre Foley-Mendelssohn

I recently discovered Literature Map, an addicting bit of artificial intelligence that plots writers by similarity. Watch your favorite authors drift about in a blue void like awkward, disembodied party-goers! A Marauder's Map for the literary. (Also good for finding new reads.) —Allison Bulger

I visited the Whitney Biennial last week and caught Sarah Michelson's disciplined performance of "Devotion Study #1—The American Dancer," a piece about movement, repetition, and the relationships formed in dance. Michelson's residency ends March 11 and it's a spectacle not to be missed. —Elizabeth Nelson

A screener of Lena Dunham's Girls made its way around the office a few weeks ago. It contained only three episodes, but I couldn't get enough. —D.F.M.

March 8, 2012

A Panorama of 'Middlemarch'

A ten-foot-tall panel illustrating the classic English novel by George Eliot. Click in and scroll down for the whole story.

Pleasure Domes with Parking

The Court of Flowers, postcard.

Because my grandfather owned a men's clothing store and my dad briefly worked for him, I spent a lot of my childhood in malls. Hanging around malls is already a tradition in Phoenix, Arizona, where I grew up. It's as central to life as driving and eating Mexican food, a habit stemming from a mix of materialism, a reflexive tendency to "pass time," and a very practical need for air conditioning. But it was also a habit born of an era when malls adorned themselves in gaudy architecture and country-and-western motifs, presented themselves as shopping experiences rather than just places to shop, and capitalized on Americans' aspirations toward glitz and glamour. I can't enter one of the predictable, interchangeable modern retail spaces without thinking of the heyday of the mall, a period when, to borrow the title of a Time magazine article, malls were "Pleasure-Domes with Parking."

I saw none of these touches of class in person. I was born in 1975, and by then malls had changed. As I experienced it, my Grandpa Shapiro's store, The Habber Dasher, was adjacent to the food court, an echoey hall enlivened by the greasy orange aroma of Pizza D'Amore and the sweet froth of Orange Julius, as well as Kay Bee Toys, the Red Baron video-game arcade, and the movie theater. My time at the mall was spent buying shockingly lifelike diecast metal cap guns at Kay Bee and then eating free samples of slow-cooked meat from the tiny gyro stall, staring in horror at the hard, sunken eyes of the whole smoked fish in Miracle Mile Deli's cold case, or looking up at the tall escalator that led into UA Cinema. When I walked through the open, indoor plaza where Santa Claus sat in a huge Styrofoam Wonderland, surrounded by polymer wads of fake snow while the sun shown outside, I had no clue that malls could be anything but what they were then, that they had any history at all.

In fact, shopping arcades and centers existed in the Western World as early as the 1920s. The classic, fully enclosed form now known in America as "the mall" debuted in Edina, Minnesota, in 1956. An Austrian-American architect named Victor Gruen designed the so-called Southdale Center, and it became the de facto prototype for a wave of enclosed, temperature-controlled shopping complexes structured around big name "anchors" and interior garden spaces. Read More »

March 7, 2012

On the Shelf

Nabokoving.

A cultural news roundup.

"Once again, it's that time of year when otherwise mature adults paint their faces in the palettes of their favorite book jacket designers, and all across Facebook college kids post pictures of themselves Nabokoving. Yes, we're talking about book awards season."

Happy birthday, John Updike!

Happy birthday, Douglas Adams!

on "bunking off."

With friends like these, Saul Bellow didn't need enemies.

Elizabeth Bowen and Jean Rhys get the "blue plaque treatment" in London.

Stephen King: "The idea that a writer can bring his core audience into the tent with a blurb ... you might as well try herding cats."

The fact that Truman Capote wrote Breakfast at Tiffany's here is a selling point. The fact that it has eighteen rooms doesn't hurt, either.

Footnotes upon footnotes in Footnote.

"Eggers named his journal after McSweeney before he knew anything about the man, and didn't discover his identity until after McSweeney died in January 2010 at age 67."

The famously combative Ben Jonson.

Jonathan Franzen: "Twitter is unspeakably irritating. Twitter stands for everything I oppose … it's hard to cite facts or create an argument in 140 characters … it's like if Kafka had decided to make a video semaphoring The Metamorphosis. Or it's like writing a novel without the letter 'P'… It's the ultimate irresponsible medium … People I care about are readers … particularly serious readers and writers, these are my people. And we do not like to yak about ourselves."

#JonathanFranzenHates

Double Fault

Three months before I was born, my father bought an eight-court outdoor tennis club on three acres of land in New Rochelle, New York. The club sits at the bottom of what amounts to a gully, down the block from a swampy lily pond that overflows during thunderstorms and floods the basements of the handsome Tudor homes in the neighborhood.

The courts themselves are made of a material called Har-Tru, a gray-green clay that smells like a mixture of coffee grounds and fresh-cut grass. It's soft and easy on the knees, perfect for middle-aged investment bankers and ad executives but more difficult to maintain than hard courts.

When it rains, the material softens, expands like a sponge, and turns into a shallow lake. During dry spells, it gets chalky and swirls around on warm breezes. Like lunar dust, Har-Tru sticks to everything. It gunks up sneakers, stains white tennis shorts, and accumulates in socks. As a kid, over the course of a given summer, I'd transfer an entire court's worth of Har-Tru to our living room.

The courts were our family's livelihood; their quality was a matter of pride for my father. Like a farmer who knows the precise chemical composition of the soil in his fields, he could step out on the courts, sniff the air, and know whether to water them or let them bake in the sun. He never read weather reports (he called weathermen "crooks") but developed meteorological instincts. He sensed drops in barometric pressure and intuited the approach of autumnal cold fronts.

"Rain's coming," he'd say, looking out over the courts like an Oklahoman homesteader.

Even when I went south to the University of Virginia, I found Har-Tru waiting for me. The company that manufactures it boasts on their homepage that Har-Tru comes from "billion-year-old Pre-Cambrian metabasalt found in the Blue Ridge Mountains." I could have walked to their corporate headquarters from the center of campus. Charlottesville has brilliant sunsets thanks to the airborne coal dust carried on the wind from mines in West Virginia. I couldn't help but stare at yellow-orange-pink skies over the Blue Ridge in autumn and think, Look at all that Har-Tru.

March 6, 2012

Two 'Paris Review' Events Not to Be Missed

This week, The Paris Review takes over New York!

This week, The Paris Review takes over New York!

Tonight, editor Lorin Stein will be at McNally Jackson with Sarah Manguso to discuss her new book, The Guardians: An Elegy. David Shields rhapsodized that The Guardians "is very pure and elemental, and I wanted nothing coming between me and the page." Don't let anything stand in your way, either; stoke your excitement for the discussion by reading our excerpt of the book here!

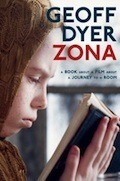

Then, on Friday, Geoff Dyer and John Jeremiah Sullivan, both contributors to our two-hundredth issue, discuss their books Zona and Pulphead at 192 Books. A man whom Zadie Smith dubbed a "national treasure" and our Southern editor in one room? We can't imagine anything better.

Then, on Friday, Geoff Dyer and John Jeremiah Sullivan, both contributors to our two-hundredth issue, discuss their books Zona and Pulphead at 192 Books. A man whom Zadie Smith dubbed a "national treasure" and our Southern editor in one room? We can't imagine anything better.

We hope to see you there!

Sarah Manguso in Conversation with Lorin Stein

March 6, 7 P.M.

Location: McNally Jackson

52 Prince Street

New York, NY 10012

Geoff Dyer in Conversation with John Jeremiah Sullivan

March 9, 7 P.M.

Location: 192 Books

192 10th Avenue

New York, NY 10011

Hari Kunzru on 'Gods Without Men'

Hari Kunzru's latest novel, Gods Without Men, is being released in the U.S. today. Set in the Mojave Desert, the novel is an echo chamber for stories divided across more than two centuries. The clever symmetries that link the stories reveal the bleached bones of American identity—racial mixing, violence, an unending contest over the politics of meaning and faith. This is Kunzru's fourth novel; his debut, The Impressionist, appeared in 2003 and was followed by Transmission (2004) and My Revolutions (2007). I conducted this interview by e-mail, but I saw Kunzru only a few weeks ago, in late January, at the Jaipur Literature Festival. He had done a public reading from Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses , a book banned in India since its publication more than two decades ago. Rushdie had been scheduled to appear at the festival but, because of threats to his life, decided to stay away. When I last saw Kunzru, it was close to midnight and he was making calls to lawyers overseas. He had been informed that he was facing arrest. The next day, on legal advice, Kunzru left the country.

The first time I read about you, you were described as having "a nonspecifically exotic appearance" that marked you "as a potential native of about half the world's nations." How do you usually explain your origins?

I was born in London. Depending on who I'm talking to, and how I feel, I might describe myself simply as a Londoner, British (that one's only crept in since I came to live in New York—to anyone in the UK, it's weirdly meaningless), English, the son of an Indian father and an English mother, Kashmiri Pandit, rootless cosmopolitan … Read More »

Join Us for Our 2012 Spring Revel

Our annual gala, the Spring Revel, brings together writers and friends of the magazine to share in an evening of cocktails, dinner, music, talk, and, all-around revelry. Just last year Women's Wear Daily called this venerable tradition "the best party in town"—and who are we to argue with WWD?

Our annual gala, the Spring Revel, brings together writers and friends of the magazine to share in an evening of cocktails, dinner, music, talk, and, all-around revelry. Just last year Women's Wear Daily called this venerable tradition "the best party in town"—and who are we to argue with WWD?

This year's going to be especially ... revelrous, because we're celebrating the two hundredth issue of The Paris Review. Comedian David Cross (Arrested Development, etc.) will give the Terry Southern Prize for Humor. Mona Simpson will give the Plimpton Prize for Fiction. Zadie Smith will present Robert Silvers, cofounder and editor of The New York Review of Books (and our sometime Paris editor), with the Hadada Prize for a "unique contribution to literature." Our Benefit Chairs are Chris Hughes, cofounder of Facebook, and his fiancée Sean Eldridge, President of Hudson River Ventures and Senior Adviser at Freedom to Marry.

We'd love to see you there! Tickets and tables are available in The Paris Review's store.

March 5, 2012

The Topographical Soul

I was at the last show of the night in a movie theater in New Orleans, and I stepped out midway to go to the bathroom. The movie was loud, cacophonous, upsetting—a documentary about Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. As I peed, I stared absentmindedly at a tile in the wall in front of me.

There was nothing remarkable about this tile, but I felt an involuntary shiver. I was alone in the bathroom, but it occurred to me that the bathroom itself had once been alone and empty—for days, weeks, maybe months during the hurricane and evacuation. It had been frozen in time like the figures in Pompeii but without any bodies to be captured in mid-life, mid-gesture. Instead, what had been captured, what resonated, was a stillness that persisted even now, after the city had ostensibly come back to life.

Cities are not meant to be emptied. Most of them never are. Even in their quietest hour they have a rustling sense of breath. But I had once spent time in another city that had also been emptied: Phnom Penh, which was evacuated under the Khmer Rouge.

Phnom Penh was, from the moment I saw it in 1994, a place that refused comparison. At first I accepted this. I had come for new experiences and I was happy, if often unnerved, to let new experiences prick me with their unfamiliarity. But then I began to feel a certain resistance in me, an effort to corral all the stimulation and make it adhere to a context with which I was familiar. I was trying, as I always did, to see Phnom Penh through the lens of my hometown, New York. Read More »

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers