The Paris Review's Blog, page 623

January 23, 2015

Politics as Usual

Al Smith in 1913.

At a certain point in the late nineties, my family’s living room needed to be rewired. It seemed the wiring had not been replaced since the house was first built. The hardware store sent up a very old man to tackle the job. I know because I was hanging around; it was summer vacation.

“I remember this house,” he said. It seemed he had worked on it as an apprentice electrician.

“In 1919?” my dad asked.

“Yup,” said the man, getting to work.

“So Al Smith had just started his first term as the governor of New York,” remarked my dad, who takes an interest in such things.

At this, the old man’s face darkened. He glowered, really.

“Goddamn Al Smith,” he muttered, furiously.

“I take it you didn’t vote for him,” said my dad.

“Goddamn Murphy. Goddamn Farley.”

“Were you a Charles S. Whitman man?” said my dad. “Did you vote Republican?”

“Yeah, I’ll vote for Whitman,” said the old man. “Hell, I’ll vote for anyone before I’ll vote for a Catholic.”

“How do you feel about Prohibition?” my dad asked casually.

“I’m for it. That Goddman Smith is in Tammany’s pocket, though. And they’re the ones making money.”

“Hm. But surely there’s a pretty big Catholic population here in town,” remarked my dad. “All the Slovakians and Croatians who … work in the copper factory.” The copper factory had been closed, at this time, for more than thirty years.

“Oh, they can work in the factories,” said the electrician, “but I don’t want them in Albany!”

“That was like being in a time machine!” my dad said later. “That guy really didn’t like Al Smith! I should have told him I was Jewish, just to see how he reacted. He’d probably never met a Jew in 1919.”

At a certain point, my Dad placed an AL SMITH FOR PRESIDENT sign in the window of our house. Sometimes he did this; he liked to rotate pieces of his political memorabilia collection. But I couldn’t help but wonder if it was for the benefit of that old electrician, and whether he saw it.

Sadie Stein is contributing editor of The Paris Review, and the Daily’s correspondent.

The Vast Beast-Whistle of Space

The literature of the fear of flying.

Photo: Corey Mitchell, via Flickr

Before takeoff, when the flight attendants are acting out the ways we’ll save ourselves in the event of a catastrophe, the same thought always occurs to me: it is possible not to fly. Plenty of people with enviable careers, even careers that require frequent travel, have managed it. The NFL’s John Madden travels across the country in his “Madden Cruiser,” a customized coach bus. Liz McClarnon, the British pop singer and member of the Atomic Kittens, hasn’t been on a plane in four years. Sean Bean (Game of Thrones’s Ned Stark) drives to all of his European film locations. He was finally forced onto a plane to shoot The Lord of the Rings in New Zealand, though he refused the helicopter ride to top of the mountain where they were filming, forcing the rest of the cast to wait while he walked up.

Those of us with aviophobia know that flying is safe—it just doesn’t feel safe. During takeoff, the plane forces itself diagonally into the air, pinning us to our seats. We feel the strain as the engines grind, trying to lift an enormous, metal, bird-shaped machine packed with humans into the sky. Why did anyone ever think this was a good idea? The air is not our natural element; the first powered plane only stayed up for twelve seconds. At thirty thousand feet, the sounds are unnerving. The poet James Dickey wrote, “There is faintly coming in / Somewhere the vast beast-whistle of space.” It’s hard to think of any sound more terrifying.

At the root of aviophobia is the fear of falling. For those of us who feel in everyday life as though the world could give out beneath us at any moment, flying is too physically close to the bottomlessness and lack of control we already feel. When you fall, there’s nothing you can do, nothing to grab onto, no one to call. Your plane becomes a plunging death capsule and you are trapped inside.

*

On July 31, 1944, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the author of The Little Prince, took off in an unarmed P-38 from Corsica and vanished. In The Pilot and the Little Prince, which contains an imagined account of Saint-Exupery’s final flight, Peter Sís rescues his protagonist from falling out of the sky. Antoine’s plane is kept aloft in a blue abyss by the Little Prince pedaling a bicycle beneath him. Sís writes, “Some say he forgot his oxygen mask and vanished at sea. Maybe Antoine found his own glittering planet next to the stars.” It’s a children’s book—of course Sís can’t send Antoine plummeting to his death. But the stories adults tell themselves about falling aren’t any less whimsical.

There is a man working diligently right now to prove his theory that Amelia Earhart’s plane did not fall out of the sky. A few months ago, Ric Gillespie claimed to have confirmed that a scrap of metal he found on Gardner Island was part of Earhart’s plane. This, he says, proves that Earhart did not crash but landed on the island, where she starved to death. There’s something desperate about this. The idea that she fell from the sky is perhaps so unconscionable to Gillespie that he’s devoted his life’s work to proving that she suffered a slower, more agonizing death.

James Dickey goes right for the final plunge in his poem “Falling.” He reimagines a real-life incident in which a stewardess was sucked out of an airplane when a door burst open. Falling, in Dickey’s version of the story, becomes sensual, erotic. Dickey undresses the stewardess, who

sheds the bat’s guiding tailpiece

Of her skirt the lightning-charged clinging of her blouse the intimate

Inner flying-garment of her slip in which she rides like the holy ghost

Of a virgin sheds the long windsocks of her stockings absurd

Brassiere then feels the girdle required by regulations squirming

Off her: no longer monobuttocked

She says goodbye to her body, celebrating her corporeal reality one final time: “she passes / Her palms over her long legs her small breasts and deeply between / Her thighs.”

The stewardess’s fall is life in miniature. She sees the ground, knows that she will die, but as she watches the ground near, “there is time to live,” and as she gets closer, “there is still time to live on a breath made of nothing.” When the ground finally approaches, she “remembers she still has time to die.” We, like the stewardess, are shuttling toward death, but more slowly, so slowly that sometimes we forget. There’s still time to live, we say. But in falling, death is laid out clearly before us. We have time to watch it approach, to meditate on it, and then to surrender to it. Life blossoms in this space before death. It is sensual and corporeal. It is with death in view that Dickey’s stewardess is “living beginning to be something.”

Is this the origin of the mile-high club? While it’s tempting to write Dickey off as a dirty old man orchestrating a striptease swan song, something rings true in his reverie. With danger in view, the stewardess’s senses are aroused. She’s hyperaware of her body now that she knows she will soon lose consciousness of it forever. She will never again remove her stockings, she will never again brush her hand across her breasts or her thighs. It’s almost over—rejoice while you can, the poem exhorts us.

Dickey, it turns out, is not really that different from the Amelia Earhart theorist or Peter Sís—he may not save his stewardess from falling, but he saves her from the ugliness of falling. What happens physically to a body when it hits the ground from thirty thousand feet? Do fragments of bone fly? Or are they eviscerated into dust? Is there anything resembling a human left? Dickey does not get into the blood and guts, though he does break the stewardess’s back. He imagines she is indented into the earth, but whole, complete, alive for one final breath and then, “AH GOD—.” God is Dickey’s version of Sís’s “glittering planet next to the stars.”

There’s no shame in these stories. They transfigure fear into a more beautiful form, allowing us to remake the world—and the world, seen from that vantage point, is better. If one day I must die in an airplane, give me S�ís’s or Dickey’s ending.

*

Or better yet, give me my own. One night, my husband and I flew to Arkansas. Terrified, I drank three airplane bottles of Sauvignon blanc in under fifteen minutes, and suddenly, I was very drunk. But the swing from fear to fearlessness was too abrupt, and I burst into tears. My husband looked up from his book stunned.

“What is it?” he asked.

I was sobbing now. “I’m so happy,” was all I could manage.

I’ve since learned that crying on airplanes is a common occurrence (as is crying during sex)—and I’m sure the drinking didn’t help. In 2011, a Virgin Atlantic survey revealed that a shocking 41 percent of men have “buried themselves in blankets to hide tears in their eyes from other passengers.” According to Elijah Wolfson, who wrote about crying on airplanes for The Atlantic, “We cry happily when we recognize, deep down, that every connection we make in life could end up severed.” From a bird’s-eye view, life below is suddenly cast in more accurate proportions. The time we spend in traffic, bickering with siblings, and shopping for office supplies is invisible from up here. We are small; our lives are brief; only a few things really matter, and soon they will be gone.

In that moment, as I was crying on the plane, helplessness was transubstantiated into joy. This three-hour flight, during which I was never once offered peanuts and sat crammed into a cabin among strangers, quickly became one of the most joyous occasions of my life. It was more joy than my wedding day, more joy than waking up at sunrise on Christmas in Burma to see backlit temples rising out of the fog. In her essay “Joy,” Zadie Smith writes that she prefers simple pleasures like eating a pineapple popsicle to the feeling of joy because tucked inside enormous joy is equally enormous pain.

Maybe I lead too pleasurable a life, but pleasure suddenly seemed too ordinary, too insignificant to fill this space between being born and dying. It’s almost over—rejoice while you can. We were thirty thousand feet in the air, headed for Little Rock, and there had never been anything more amazing. Our lives were at the mercy of the pilot, the weather, the machine, and one another. We could plunge at any second—and finally, I was okay with that. I thought of the Sean Beans and John Maddens of the world, bested by fear, stubbornly maintaining the illusion of control as they bus and train across terra firma. There’s something so hopeless, so undreaming, about staying down there.

I was in the air, and I saw flying for what it was: to fly is to insist on the ethereal in a weighted world. My plane emerged from the clouds leveling off into the nighttime. If you could’ve somehow seen our bodies without the plane, you would have seen rows of humans two by two, reading, talking, listening to music, suspended in the night sky.

Laura Smith is a writer based in New York. She is currently working on a book about Barbara Newhall Follett, who disappeared in 1939.

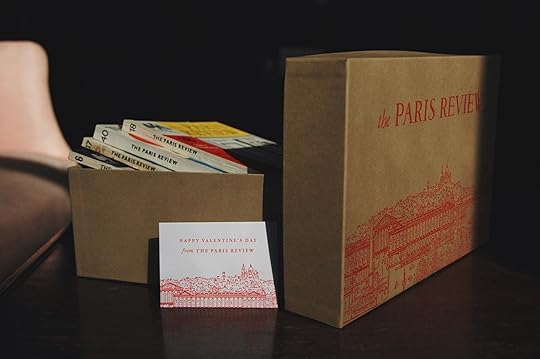

Show Your Affection with Vintage Issues of The Paris Review

Photo: Stephen Andrew Hiltner

It’s not easy to describe matters of the heart. Even Shakespeare sometimes got it wrong: “Love is a smoke,” he wrote in Romeo and Juliet, as if we’re all human cigarettes, burning ourselves down with romance.

But Valentine’s Day is mere weeks away, and if we want to make a good impression, it behooves us to use our words—our best words. Fortunately, The Paris Review’s archive is full of writers, more than sixty years’ worth, who know all the right things to say.

That’s why we’re offering a special Valentine’s Day box set: choose any three issues from our archive, and at no extra charge, we’ll package them in the lovely gift box you see above, including a card featuring William Pène du Bois’s 1953 sketch of the Place de la Concorde. (You may have seen it on the title page of the quarterly, or in the footer of our Web site.) Then they go straight to the home of your significant other.

You’ll find all the details here—orders begin shipping next week, and delivery before Valentine’s Day is guaranteed if you order by February 10.

How Not to Preserve Ancient Scrolls, and Other News

A replica demonstrates how a scroll might have looked when it was new. Photo: Giovanni Dall'Orto, 2014

Resolve your literary feud the media-friendly way: (1) do it at a public event, (2) make sure there’s not a dry eye in the house, and (3) invoke the memory of Charles Dickens, just for the sport of it. More than fifteen years ago, V. S. Naipaul and Paul Theroux “fell out in a spectacularly-bitter war of words, after Naipaul sold some of Theroux’s gifts at auction. The anger seethed for almost two decades. But on Wednesday the hatchet was resoundingly buried, with eighty-two-year-old Naipaul breaking down in tears after Theroux praised one of his most famous books at a literary festival in India, and compared the author to Charles Dickens.”

Centuries ago, an excavation in Italy revealed a collection of some two thousand ancient Roman scrolls, most of them treatises on Epicurean philosophy. Unfortunately, the scrolls have a tendency to crumble in your hands, which makes it fairly difficult to read or even preserve them. People have tried taking knives to them (didn’t work), applying a gelatin-based adhesive (didn’t work), or just throwing them away (didn’t work). The latest solution: X-rays.

The architect who bought Ray Bradbury’s Los Angeles house demolished it earlier this month, thus unleashing a furor from Bradbury fans. “It’s really been a bummer,” the architect said, adding in his defense that the home was exceptionally bland. “I could make no connection between the extraordinary nature of the writer and the incredible un-extraordinariness of the house.” Yesterday he hatched a new plan to honor the space: a wall.

On Quvenzhané Wallis’s black Annie: “the fact that a black Annie has arrived on the scene at this particular cultural moment seems to me cruelly ironic … When it comes to persuading Americans about the virtue of selfishness, Ayn Rand has nothing on Annie … By making innocence seem invulnerable, Annie and other Teflon kids in fiction and film have helped to enable the widespread apathy about social inequalities that allows Americans to claim that our society is child-centered even though the percentage of children living in poverty in this country continues to grow.”

Has technology accelerated life to the point of meaninglessness? On Judy Wajcman’s Pressed for Time: “Wajcman recalls seeing, at a nursing home, a daughter with one arm slung around her elderly mother, the other tapping on her smartphone. Though Wajcman acknowledges an initial negative judgment of this scene, she quickly reconsidered. The elderly mother was clearly not very aware of her surroundings and was likely comforted by her daughter’s presence. The daughter was able to provide this solace while engaging in other activities. (She could also have been reading a book or magazine.) Is this really to be condemned?”

January 22, 2015

Crunchy Systems

Borna Sammak, Untitled, 2015, heat applied T-shirt graphics and embroidery on canvas, 40" x 30". Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. Photo credit: Jason Wyche

Long before crunchy found a thrilling new life as a pejorative for hippies, the journalist Nico Colchester used it to describe a set of economic conditions: “Crunchy systems,” he wrote, “are those in which small changes have big effects leaving those affected by them in no doubt whether they are up or down, rich or broke, winning or losing, dead or alive … sogginess is comfortable uncertainty.”

“Crunchy,” a new group show Marianne Boesky Gallery, takes its inspiration from Colchester’s definition, though it owes just as much to the word’s new, granola-centric connotation. Organized by Clayton Press and Gregory Linn, it collects essentially tactile paintings—the hard, the crisp, the agreeably sharp. “It is about the materiality of material,” they say, which sounds tautological until you look at the paintings, all of which induce various forms of synesthesia. You’ll want to bite some of them. Don’t—don‘t make the same mistake I did. There are no flavors there.

“Crunchy” is up through February 21.

Anna Betbeze, Muff, 2015; acid dyes, ash, wool; 61" x 80"

Anthony Pearson, detail from Untitled (Plaster Positive), 2013, Pigmented hydrocal in walnut frame, 43 1/2" x 31 1/2" x 3". Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. Photo: Jason Wyche

Installation view. Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York; photo credit: Jason Wyche

Ethan Greenbaum, Post, 2015, direct to substrate print on vacuum formed PETG and spray enamel, 41 3/8" x 48 1/8". Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York; photo credit: Jason Wyche

True Romance

Byron, meditating on mortality, no doubt.

’Tis time this heart should be unmoved,

Since others it has ceased to move:

Yet, though I cannot be beloved,

Still let me love!

My days are in the yellow leaf;

The flowers and fruits of Love are gone;

The worm—the canker, and the grief

Are mine alone!

So begins one of Byron’s last poems. Is it an ode to the Greek youth he loved? A general meditation on mortality? Choose your theory. The date, at least, we can estimate with a fair degree of accuracy. In the 1825 Narrative of Lord Byron’s Last Journey to Greece, his friend, Count Gamba, related of the occasion:

This morning Lord Byron came from his bedroom into the apartment where Colonel Stanhope and some friends were assembled, and said with a smile—“You were complaining, the other day, that I never write any poetry now:—this is my birthday, and I have just finished something, which, I think, is better than what I usually write.” He then produced these noble and affecting verses, which were afterwards found written in his journals, with only the following introduction: “Jan. 22; on this day I complete my 36th year.”

The notorious poet would die in April of the same year, 1824, in Missolonghi. The prophetic nature of the poem may have been because of a new awareness of death; Byron’s friend Shelley had died in 1822, his daughter Allegra a year later. After years of hedonism, Byron was facing the realities of violence. Then, too, the baron lived hard, consuming alcohol with legendary intemperance. Although he would ultimately die of a fever, he’s believed to have suffered a small stroke shortly beforehand.

Yesterday, a friend and I were discussing how inured we—the global “we”—are to shock. Is there anything that could shock you today? We wondered. Has there been anything? More often than not revelations provoke a sense of sadness, or maybe disappointment, but even then it doesn’t feel wholly unexpected. On those few occasions I’ve felt a momentary pang, I chided myself for my naïveté. (The end of my own innocence was marked by the charges against my beloved Frugal Gourmet. I’d always dreamed of going on his children’s Christmas specials.) Can you imagine enjoying shock?

To this day, people speak with relish of Byron’s scandals, his sexual liaisons and illegitimate children, his beauty, and his debauchery. I’ve heard him described as one of the first modern celebrities—at least, in terms of calculated image control. Of course, Byron was a nobleman, and so well-placed to scandalize polite society. But at the end of the day, it truly was his verse that caused such a sensation. Even in our jaded times, a rich man being accused of incest and driving a society matron to a suicide attempt would make Page Six. But say that guy were a poet—would his work then start selling? Would it be read with scandalized glee and prompt a thousand admirers and imitators? That, at least, might be genuinely shocking.

Sadie Stein is contributing editor of The Paris Review and the Daily’s correspondent.

John Bayley on British Wit

John Bayley with Iris Murdoch, 1980.

The New York Times has reported that John Bayley died last week at eighty-nine. A literary critic and Oxford don, Bayley was best known for his vivid, searching memoir, Elegy for Iris, about his married life with Iris Murdoch, who in the late nineties had fallen deep into Alzheimer’s disease. “To feel oneself held and cherished and accompanied, and yet to be alone,” he wrote. “To be closely and physically entwined, and yet feel solitude’s friendly presence, as warm and undesolating as contiguity itself.”

But Bayley was a keen critic, too. Remembering him in the Guardian, Richard Eyre writes,

John was a brilliantly readable reviewer, often witty and sometimes waspish, but invariably bearing the authority of a man who could speak knowledgeably of all European cultures. He believed that the point of literature was to make sense of the world, and, although shy and unassertive, he was a blazingly confident guide to how and where to discover those truths. If I were looking for an epitaph for him it would be from Tolstoy: “We can know only that we know nothing. And that is the highest degree of human wisdom.”

In our Spring 1998 issue, The Paris Review asked thirteen British writers to answer questions about the state of the nation’s literature. Bayley was one of them—here, to remember him, are the two questions he answered.

Why is wit so strongly indigenous to British writing?

I’m not sure the English novel, taken as a whole, is particularly witty but I am sure it’s full of humour. There’s not a clear distinction between the two but there is a difference. Jane Austen is both witty (see the first sentence of Pride and Prejudice) and humorous, but her humour goes deeper, is less comprehensive, less definable. Why should it be so funny for instance when Emma’s father Mr. Woodhouse—himself a wonderfully humorous portrait—keeps boring his family and the reader with some riddle about “Kitty, a fair but frozen maid.” It doesn’t sound funny here but in the book it is—very funny—and as with all true humour one can’t really say why. Barbara Pym, a contemporary novelist and in a sense a disciple of Jane Austen, is very funny too in this way if you like her novels—some people don’t. Humour, like taste, is unaccountable.

P. G. Wodehouse (no relation of Jane Austen’s family in Emma) comes into a third category: he makes jokes. Sometimes the jokes don’t come off: more often they do. And they can also be both witty and humorous, like the man “who looked as if he had been poured into his suit and forgotten to say ‘when.’ ” That is good-natured, like all humour. Henry James can be much sharper but equally humorous, as when he says that a society lady is “like a creature who perched upon twigs.” If he had said “like a bird” it wouldn’t have been funny at all. As it is, there is a grotesque element in the idea of an elderly woman twittering away among the branches that is irresistibly comic. And true humour animates a novel more than anything else.

Does the Booker ever get it right?

Having been a Booker chairman myself, I don’t see how it can. One of the joys of the novel is that no two readers agree about the merits of any single one of them. It is the most subjective form in the whole spectrum of art. If War and Peace were to be submitted, he can be quite sure that the jury would split fifty-fifty. Half of them would say it was too long, contained too much boring history, was too much about the upper classes … no novelist can ever do more than please some of his readers for some of the time, and that is how it should be.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

The Post-Šalamunian Period

Remembering Tomaž Šalamun.

Salamun at the Spier Poetry Festival, 2014. Photo: Retha Ferguson

I had written to tell Tomaž Šalamun he’d changed my life—thanks to him, I’d begun to put down roots in a new continent, and met the woman I was going to marry. I had at least assumed I could take him out to dinner on his next visit to the U.S. The letter went unanswered for a couple of weeks and then a reply materialized in my inbox. “With my last strength I greet you,” he wrote, dictating the letter to his wife, the painter Metka Krašovec, “enjoy the States, I think this is the best place for you.” Five weeks later, on December 27, 2014, Šalamun passed away in his beloved Ljubljana.

I had only met him once, at a festival on a wine estate outside Stellenbosch in 2013, but he had made an immediate and lasting impression. It took me a few days to shape my speechlessness into an answer. “He is calm and patient,” Metka assured me in her postscript, “and he accepted his death the moment he found out about his cancer.” I had assumed he was all but immortal, sustained by the unfettered vitality that electrified all of his poems. After all, this was the man who beat Lucretius up his ass, thought killing smelled good, stuffed Mitteleuropa with shine and “cut off [her] claustrophobic head with a clasp knife”; who paused halfway through a poem to wonder how he would make love that day, “will I be like a pasha, a conquistador, will I/tremble, amazed and quiet?” It was thus greatly distressing to learn he’d spent the last three months of his life suffering from such vertigo that it left him unable to read, write, or walk by himself. I had sensed a hint of frailty during our time in South Africa. During a weekend at a farm on the banks of the Berg River, our host had offered to take us on a ride through his holdings, and although I’d seen Tomaž eye the horse somewhat longingly, he’d excused himself saying he’d hurt his back, but didn’t tell us how. I wish he had: as Christopher Merrill informed us in his elegant tribute, Tomaž injured himself tobogganing down the Great Wall of China. Of course he had.

Famously wild with his words, Tomaž was also renowned for his generosity toward younger poets. During the festival, I’d mentioned how I’d grown tired of Europe, and believed the continent was sleepwalking into a form of creeping fascism; he immediately suggested I apply to various American artists’ colonies, and when I replied that I hated the thought of asking anyone for a reference, he slapped me on the shoulder and said he’d take care of it. True to his word, I found a parcel of references waiting for me on my return from South Africa, and a couple of months later I left Europe for good. Helping younger writers wasn’t mere kindness—it was part and parcel with his vision of the world, an acknowledgement that each generation constituted a vital vertebra in the backbone of humanity. A few pages into The Revolt of the Young, the Egyptian writer Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm makes an impassioned plea: “Intellectuals, before all others, should look ahead to the intellectual life of the years to come and make preparations for others to take their place, paving the way for new talents to appear and ripen. The question, ever in the mind is, what will happen in the next ten or twenty years?”

Few poets understood this better than Tomaž Šalamun. In “Duma ’64,” the celebrated poem which earned him five days in prison—mostly because he’d unwittingly lampooned the Minister of the Interior by calling him a “dead cat”—he had satirized his country’s “fawning intellectuals” and their “small sweaty hands,” frustrated by “rectors with muzzles on [their] snouts,” and “mummies who applaud[ed] passions and sufferings in an academic way.” Poets had to do more than that. Raised in a country that pompously declared five-year plans could be achieved in four, Tomaž insisted on highly individual poems that irreverently bared all our cruelty, hypocrisy and callowness for all to see. Dictatorships have always despised comedians and poets, and with good reason: as James Baldwin once wrote, “for power to feel truly menaced, it must somehow sense itself in the presence of another power—or, more accurately, an energy—which it has not known how to define and therefore does not really know how to control.”

Adults tend to find children creepy—even worse, uncontrollable—which perhaps explains why they feature so heavily in our horror films, and Tomaž took the notion of the enfant terrible to its logical conclusion. Much of his genius lay in unearthing the childlike sense of wonder most adults tend to suppress in order to help steer our minds towards uncomfortable truths. Tomaž’s children could be cruel, gleeful, or scared, but they were never anything less than human. He could also accomplish this with great humor. Take the opening lines of “Duomo”: “When they gave orders to make me pants for first/communion they cut them as shorts. So I went to/confirmation as a boy scout too. On the way, I kept/killing rats with my keys. I was afraid they would eat my/bike.”

Inspired in equal parts by Russian futurists, French surrealists, and New York School poets, as Colm Tóibín noted, Tomaž was nevertheless too slippery to be compared to anything. His poems will continue to defy categorization, but they will be remembered for the way they walked the tightrope between ecstasy and despair, the rational and the irrational, the sublime and the horrible. At his finest, Tomaž could even achieve this in less than twenty-five words:

RAIN

It rained during the night.

Did the snails sleep or paddle?

The pine tree strained itself and grew for a millimeter

and there, far away, Lebanon was bombed.

Published in 1985, but only translated into English in 2014, the poems in Soy Realidad were some of the last Tomaž would write for a while. By his own admission, he didn’t pen a single poem from 1989 to 1994, and even suffered a breakdown while in residence at Yaddo. He, too, had his problems, but he held fast to his sense of adventure, both personally and creatively. Though I didn’t know him for long, I will miss him greatly.

Over the past few weeks I’ve thought of that old proverbial rhyme, “for want of a nail,” whereby the loss of a horseshoe cripples a horse, toppling a knight whose dispatch then isn’t delivered—turning the tide of the battle and ending in the loss of a kingdom. “Well, maybe the kingdom was ruled by an evil dictator,” Tomaž might have said. He believed poems should have happy endings. “It is strange,” Metka wrote in a recent letter, “isn’t it, how life brings people together even for a very brief moment and how that can change a lot of things.”

ABOUT HEAVEN AND EARTH

In the post-Šalamunian period,

in the year of our Lord three,

while cooking chicken as per Metka’s

instructions, to save a little, and

to need not go to the earth

too soon;

I watch the sunset and tell

myself: I know,

the sun is in my chest.

What will they do

if I don’t give it back.

Better throw this counting

in their head.

Call the number, the taxi will

take you to the plane.

Soy Realidad: Poems, translated by Michael Thomas Taren and Tomaž Šalamun, was published in September 2014.

A marathon reading of texts and poems in honor of Tomaž Šalamun will be held at the Mini Teater in Ljubljana on February 3. The event will be broadcast on RTV Slovenija and globally via Skype.

André Naffis-Sahely’s poetry was most recently featured in The Best British Poetry 2014. His latest translation is The Physiology of the Employee by Honoré de Balzac.

People Are Still Liars, Leading Thinkers Say, and Other News

Franz von Stuck, Adam and Eve, ca. 1920.

John Berger goes for a swim: “I have my favourite municipal swimming pools, where I go to swim up and down at my own pace, crossing other swimmers whom I don’t know, although we exchange glances and sometimes smiles … As swimmers we share a kind of egalitarian anonymity. No shoes, no marks of rank, just our swimming costumes. If you accidentally touch another swimmer while passing him or her, you offer an apology. The limitless cruelty towards others like ourselves, the cruelty of which we are capable when we are regimented and indoctrinated, is difficult to imagine here.”

Do you have $300,000? Give it to James Patterson. (He needs it, right?) These are the things he’ll give you in return: “a first-class flight to an undisclosed location, two nights stay in a luxury hotel, fourteen-carat gold binoculars, a five-course dinner with the author, and a copy of Private Vegas that will ‘self-destruct’ twenty-four hours after the purchaser begins reading it. The precise nature of the explosion has not been revealed, but it is believed to involve a bomb squad and an exotic location.”

Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper has broken box-office records largely by attracting white men from Middle America—not typically a movie-going lot—and so finds itself at the center of the culture wars. Is the movie mere war propaganda, as its critics avow, or are its fans just intent on reducing it to jingoism? “Go ahead and attack Eastwood for making a movie that’s totally uninterested in the underlying politics of the Iraq conflict, and that depicts its Arab characters in cursory and stereotypical terms. That’s entirely legitimate, and indeed I think those America-centric aspects partly undermine the film’s aims. But to assign Eastwood some Bush-Cheney war-booster agenda because he supported Mitt Romney in 2012, or even because some unknown proportion of moviegoers have seized on it that way, simply isn’t fair.”

On the problem of lying, which still gets people riled up and has been linked since at least the earliest days of the Christian church to “the problem of human existence itself”: “We all do it, and we all damn it. In many traditions, both Western and Eastern, it is considered among the most blameworthy of acts … I have friends who could laugh off being called an adulterer but would storm out of the room if I said, ‘You’re a liar.’ ”

Not unrelatedly, it turns out that “the truly unique trait of Sapiens is our ability to create and believe fiction. All other animals use their communication system to describe reality. We use our communication system to create new realities.”

January 21, 2015

The Ants of God

The budding South Sudanese community in Omaha, Nebraska.

A still from The Nuer, a 1971 documentary.

More than a hundred years ago, my relatives emigrated from Czechoslovakia to Nebraska, thus escaping the privilege of becoming fodder for the aristocracy’s canons. Why Nebraska? The railroad advertising pictured illustrations of the thick loam of the prairie, calculated to resemble their homeland’s. The land was theirs for free if they worked extremely hard on it for five years, and many did, and prospered.

This century, the Nuer from South Sudan have immigrated to the same region, but they aren’t so fortunate. Having escaped one of the world’s worst war zones, endured extremely harsh conditions in refugee camps, and traveled eight thousand miles to resettle, the Nuer face poor Nebraska neighborhoods policed by gangs like the Bloods and the Crips.

The Nuer fled fighting in a very remote area in South Sudan, much of it accessible only by boat or on foot. I know. I walked into the region thirty-five years ago, lugging in heavy sound equipment to make a sequel to The Nuer, the highest grossing ethnographic film of the time. The original, from 1971, was extremely beautiful, shot by Hilary Harris, Robert Gardner, and George Breidenbach. It documented the traditional Nuer lifestyle as depicted by E. E. Evans-Pritchard, the British academic who founded the discipline of social anthropology on a study of their culture. The sequel to it was never finished, but I translated and published Cleaned the Crocodile’s Teeth, a selection of their songs, their most complex art form.

Never would I have imagined that people from so far away would move within a hundred miles of my birthplace in Ogallala, Nebraska. So many resettled in the state that it now has the world’s largest population of Nuer outside South Sudan. Had I impressed them with talk of a landscape similar to their own, the way the broadsides had lured my relatives? It couldn’t be—all I’d had to do was mention snow to the Africans and their enthusiasm waned. Originally, resettlement agencies sent the Nuer to rural Minnesota, Virginia, Arizona, California, and upstate New York. They had to establish themselves quickly: all our government gave them was a loan for the plane ticket from Africa, less than three hundred dollars cash, and food stamps. They had to start paying back the loans within six months—a tall order when you’re traumatized by war, not yet fluent in English, and largely unaware of American customs. Through informal cell phone networking, the Nuer converged on Nebraska. Cheap housing attracted them—and openings in the meatpacking industry, that mainstay of immigrant labor. In many Nuer families, both spouses work two shifts. The slaughterhouse was a psychologically difficult workplace, as they had just fled a war that had more civilian casualties than World War II. The slaughterhouse worker I spoke to was bothered by the screams of the half-dead cattle while their hides were ripped off with hooks. You are supposed to wait until the eyes tell you what to do, he said.

Economic reliance on cow culture is a bit of an embarrassment to urban Nebraskans, with four times as many cattle than people in the state. Cow culture for the Nuer, however, is everything. In the film The Nuer, the barren savannah is filled with cattle staked to the ground, lowing. African Nuer love cattle and give each animal a name appropriate to its hide and horns. Rather than eat them, they breed them for bridewealth. During my stay in Nuerland, when one suitor became too ardent, I reminded him that my father would have to send his cattle for the wedding by airplane. He did not see that as a serious impediment. A young Nuer in Nebraska now sends money in remittances home to South Sudan to buy cattle for his marriage, on average five thousand dollars a year out of what is most likely a minimum wage job. After accomplishing this, he saves up again to fly to South Sudan and collect his wife.

*

I gave a talk at the state university a few years ago on the parallels between Nebraska and South Sudan. Flat land, flat river—the Platte that bisects the state is not so dissimilar from that part of the Nile. Both parts of the world host big fish (two hundred pound Nile perch to Nebraska’s hundred pound catfish) and big birds (whooping cranes and pelicans nest in both Nebraska and South Sudan). I showed slides of the sod houses the early white settlers built and the beautiful mud-and-wattle structures of the Sudanese Nuer. Living was difficult for my ancestors, too—eighty-hour weeks, no electricity, little plumbing, few cars. In exchange, they had star-studded endless skies, a humane pace of living, and song.

Everyone sang in Nuerland, too—their own songs, their neighbors’, and their forebears. If they wanted accompaniment, they dug a hole for a bass drum and strung it with a fret made of giraffe hair. My great-great grandparents owned a violin and a psalm book. They, too, doted on their cattle, fastening little wooden clappers around their necks, not unlike the way the Nuer threaded tassels through the horns of their cattle.

I ended the presentation by reading a few of their songs in translation. When I asked for a member of the audience to sing one in the original, no one volunteered. Was it because of the news they’d had right before arriving, of a Nuer woman committing suicide? The adjustment to such a radically different way of life, and the discovery of American racism, has driven refugees to suicide, especially women who often find themselves shut out of their children’s lives linguistically, if not culturally. Attempting suicide for my ancestors was so common on the frontier that the asylum was often the first public building erected. I was very surprised when, at the last minute, one of the business-suited Nuer men strode up to the podium—and brought down the house.

Martha Kiir sings for Bob Holman’s Endangered Languages project. Photo: Terese Svoboda

Some of the girls in the audience had been involved in The Quilted Conscience, a film about teenage girls from South Sudan I helped produce. They made a quilt with local Nebraska women, sewing together designs that represented their hopes for their future and their memories of the past. In South Sudan, the possibility of dying at childbirth was higher than a girl going to secondary school. But these immigrant kids had ambitions. One of the girls proved herself in high school by playing football with the boys—in Nebraska, a state where men rule the ball. To reward such perseverance, I give a small scholarship to high school graduates to those who honor the Nuer tradition in poetry of song. I look for someone who can see the triumph of what it is to become an American, and who also feels the poignance of a lost homeland. The immigrant writer is essential to American literature because too often its citizens forget why they live here, and not elsewhere. With airplanes and life rafts, nationhood seems so porous—unless you really need to get away, like the children caught at Mexico’s border, or the South Sudanese Lost Boys who walked their way out of war.

Buey Ran Tut arrived in Omaha at age eleven. Obama-handsome, he gave a TED talk in October. After a decade as a refugee, Tut was vice president of the student body at the University of Nebraska, a member of the Omaha Public Library Board, a district executive for the Boy Scouts, and co-founder of Aqua Africa, a nonprofit concerned with clean drinking water. He and his partner, Buay Wiyual, a Dinka—traditionally rivals in Africa—have drilled sixteen wells in South Sudan in only four years. His is hardly an isolated example of Nuer efforts to help themselves, just the most visible to Nebraskans, who have their own water problems.

*

This July, a woman named Nyadhiel Joak found me on Facebook. Thirty-five years earlier, her father, Ret, had fed and housed me in Malakal, a stop of over 100,000 South Sudanese on the confluence of two branches of the Nile. I was collecting Nuer song and Ret was a government official. “I am a big man,” he told me. “I care for so many.” Along with foreign guests like myself, he housed at least ten of his extended family alongside his own four children. Joak wanted to know what the inside of his house looked like. I told her I slept in a room with a single iron bedstead without a mattress; Ret, his wife Nyagak, and three of their children slept in the only other room. Everyone else found a place on the cement slab of his porch or in the dusty backyard. Late into the night, Ret’s colleagues from work convened in that backyard, to eat and drink, to plan political moves, to flirt with the women, and to sing. “The ants of god,” they called themselves in one of the songs I recorded there—a phrase that emphasized their vulnerability to the harsh climate of the savannah, their capacity for hard work, and their cooperative yet anarchic nature. Evans-Pritchard observed of them: “There is no master and no servant in their society, but only equals who regard themselves as God’s noblest creation.”

After my stay with Ret and his family, I searched for more songs, traveling further south to Nasir. Three months later, a single-engine plane counting cattle for tax purposes landed in my front yard and offered to fly me out. The annual drought had begun, and there were food riots every morning. Unlike most Nuer in exile, I could go home. Serious warfare broke out soon after I left. Ten years later, Ret Chol was murdered in the civil war before he could take up his post as an ambassador. His family fled to Egypt, Australia, Canada. Malakal was burned to the ground.

*

In 2011, the year before South Sudan became a new nation, I gave the vice president, Riek Machar, a copy of my translations of songs. I sat next to him on a couch in Juba airport’s VIP lounge and we chatted for half an hour—I played the white woman’s card, since he had been married to an Englishwoman years earlier. Affable yet cagey, Machar asked why my book was missing the original Nuer for the songs. Embarrassed, I explained that the tiny press that published the book so many years ago had no way to reproduce the Nuer orthography. I spent the next summer producing a coffee-table version with the Nuer transcription from my original manuscript. A year later, I found someone to deliver it to Machar’s office.

Civil war broke out a week later. Machar fled Juba as the putative leader of a rebellion. South Sudan now has tens of thousands dead, 1.5 million displaced, five million on the brink of starvation. The World Food Program has been attacked while trying to feed thirty-seven thousand hungry people. One side has stockpiled thirty-eight million dollars in Chinese arms, sold to them by the oil pipeline’s biggest stakeholder. Amnesty International is begging the UN Security Council to impose an embargo. The political issue of the war appears to be the states rights versus federal, a struggle the U.S. should be able to understand, an especially acute question during our first years as a nation. Three Nebraskans were among the first to die in the fighting that claimed twenty thousand Nuer in December. They had returned to help set up the country.

In Nebraska, the Bloods and the Crips and other Omaha gangs view the Nuer immigrants as naive, as hicks from the boondocks. The state has the highest rate of black homicide victimization in the country. Driving along the interstate, a Nuer friend pointed out for me which ridges were helpful for snipers, what terrain would put someone unfamiliar with the prairie at a disadvantage. He also mentioned that along with lullabies and dancing lyrics, the book I gave Riek contained a section of songs by Nuer prophets that traditionally rallied those involved in warfare. This was one time I hoped poetry did nothing.

Terese Svoboda's biography Anything That Burns You: Lola Ridge, Radical Poet will be published next year. When The Next Big War Blows Down The Valley: Selected and New Poems will be published this year.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers