The Paris Review's Blog, page 626

January 15, 2015

They Never Slept, and Other News

Mona Simpson (a Paris Review alumna) remembers Robert Stone: “He’s certainly not sentimental about the counterculture, or for that matter about much else … In a sense he’s definitely writing about our confrontation with other cultures and what that does to the souls and psyches of the people who are doing that, who are not necessarily the people who plan to do that.”

Whatever became of the Pinkertons? The history of the nineteenth century’s premier “national detective agency”: “During the early 1890s, the Pinkertons, as they were more commonly known, had boasted a force of 2,000 active operatives and some 30,000 reserve officers. By comparison, the United States Army, which for decades had been primarily concerned with fighting Native Americans in the West, had fewer than 30,000 officers and enlisted men assigned to active duty. To their enemies—usually the labor unions—the Pinkertons were a private militia at the beck and call of industrialists, bankers, and other agents of capitalism. The state of Ohio outlawed the Pinkertons for fear that they could form an army outside the purview of the American government.”

Cangrande della Scala, an Italian nobleman and patron of Dante, died under mysterious circumstances in 1329; many have wondered if he was poisoned. The key to the mystery: his mummified feces.

Francine Prose was reading an e-book edition of Vanity Fair, until she got the news that e-book retailers can see what percentage of your books you’ve finished: “As soon as I get home, I’m putting away my e-book and opening my volume of Thackeray. I will happily bear its weight … I don’t like the feeling that a stranger (electronic or human) is spying on my sojourn in Vanity Fair. Whether or not I finish a book will be a secret between me and my bookmark, and someday my grandchildren may be interested (or not) to see when I quit dog-earing the corners of the pages.”

“What can political cartoons do beyond messages of solidarity? We might look at how Arab cartoonists have responded to their own local and national conflicts … When Westerners were decapitated in Syria this past August, cartoonists made light of the Islamic State’s campaign of terror … While the world recoiled with revulsion at the executions, cartoonists unveiled imagery that shocked in order to shame the Islamic State jihadis and other extremists. This is offensive. This is also Muslims critiquing Muslims. Beheading cartoons are an answer to anti-Muslim chatter, and that vapid intonation of ‘Where are the moderate Muslims?’ They’re drawing.”

January 14, 2015

“Good hearted Naiveté”

DOS PASSOS

Ernest and I used to read the Bible to each other. He began it. We read separate little scenes. From Kings, Chronicles. We didn't make anything out of it—the reading—but Ernest at that time talked a lot about style. He was crazy about Stephen Crane's “The Blue Hotel.” It affected him very much. I was very much taken with him. He took me around to Gertrude Stein's. I wasn't quite at home there. A Buddha sitting up there, surveying us. Ernest was much less noisy then than he was in later life. He felt such people were instructive.

INTERVIEWER

Was Hemingway as occupied with the four-letter word problem as he was later?

DOS PASSOS

He was always concerned with four-letter words. It never bothered me particularly. Sex can be indicated with asterisks. I've always felt that was as good a way as any.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think Hemingway's descriptions of those times were accurate in A Moveable Feast?

DOS PASSOS

Well, it’s a little sour, that book. His treatment of people like Scott Fitzgerald—the great man talking down about his contemporaries. He was always competitive and critical, overly so, but in the early days you could kid him out of it. He had a bad heredity. His father was very overbearing apparently. His mother was a very odd woman. I remember once when we were in Key West Ernest received a large unwieldy package from her. It had a big, rather crushed cake in it. She had put in a number of things with it, including the pistol with which his father had killed himself. Ernest was terribly upset.

—John Dos Passos, the Art of Fiction No. 44, Spring 1969

When Hemingway and Dos Passos—who was born on this day in 1896—went to Spain during the civil war, they were close friends, though it was an odd, uneasy match. They’d met in Paris, but their personalities couldn’t have been more opposed: reticent Dos Passos didn’t go in for the Hemingway model of chest-thumping virility.

He was a much more overtly political writer than Hemingway, and when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, he was at the apex of his popularity, having appeared on the cover of Time to commemorate his new novel, The Big Money, the third installment of his USA trilogy. That meant he was, for the first and last time, on equal footing with Hemingway, which can’t have sat well with the latter.

Both writers were moved to action by their support for the Loyalist government, and so both embarked for Spain, Hemingway having contracted to write dispatches for a newspaper and Dos Passos having agreed to help with a documentary about the war.

What happened next is murky. Dos Passos arrived in the spring of 1937 expecting to meet an old friend of his, José Robles. As George Packer explained in a 2005 piece for The New Yorker,

José Robles was a left-wing aristocrat … [but] maintained enough independence of mind to raise an alarm among pro-Communist Spanish authorities and the Soviet intelligence agents who, by early 1937, were bringing the government increasingly under Stalin’s control. Dos Passos was counting on Robles to serve as his main Spanish contact on the film; but by the time the two American novelists reached Madrid, separately, Robles had disappeared. It was Hemingway who learned first … that Robles had been arrested and shot as a Fascist spy. To this day, the manner and motive of Robles’s death remain a mystery …

Hemingway broke the news to his friend, but apparently he was impolitic about it—and so began their falling out, with Dos Passos vouching for Robles and Hemingway laughing at his naïveté.

Dos Passos’s response to his friend’s disappearance reflected his sense that progressive politics without human decency is a sham. Hemingway, in a thinly disguised magazine article about the episode published in a short-lived Esquire spinoff called Ken, described these scruples as “the good hearted naiveté of a typical American liberal attitude.” Bookish, balding, tall and ungainly, sunny in temperament, too trusting of others’ good will: Dos Passos was the sort of man who aroused Hemingway’s sadistic appetite. “White as the under half of an unsold flounder at 11 o’clock in the morning just before the fish market shuts” was one of Hemingway’s fictionalized descriptions of his old friend.

Dos Passos mentions none of this in his Art of Fiction interview—there are only those pleasant recollections of the pair reciting the Bible to each other. He was too disillusioned to write about it, meaning that Hemingway’s accounts came, by virtue of repetition, to seem real. In A Moveable Feast, published after his death, Hemingway further maligned Dos Passos, implying that he was a slippery, duplicitous “pilot fish.” Still, Dos Passos said only that he found the book “a little sour.”

If you’re curious about their friendship, and what Spain did to it, check out Stephen Koch’s The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of José Robles.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

“Good-hearted Naiveté”

John Dos Passos

DOS PASSOS

Ernest and I used to read the Bible to each other. He began it. We read separate little scenes. From Kings, Chronicles. We didn't make anything out of it—the reading—but Ernest at that time talked a lot about style. He was crazy about Stephen Crane's “The Blue Hotel.” It affected him very much. I was very much taken with him. He took me around to Gertrude Stein's. I wasn't quite at home there. A Buddha sitting up there, surveying us. Ernest was much less noisy then than he was in later life. He felt such people were instructive.

INTERVIEWER

Was Hemingway as occupied with the four-letter word problem as he was later?

DOS PASSOS

He was always concerned with four-letter words. It never bothered me particularly. Sex can be indicated with asterisks. I've always felt that was as good a way as any.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think Hemingway's descriptions of those times were accurate in A Moveable Feast?

DOS PASSOS

Well, it’s a little sour, that book. His treatment of people like Scott Fitzgerald—the great man talking down about his contemporaries. He was always competitive and critical, overly so, but in the early days you could kid him out of it. He had a bad heredity. His father was very overbearing apparently. His mother was a very odd woman. I remember once when we were in Key West Ernest received a large unwieldy package from her. It had a big, rather crushed cake in it. She had put in a number of things with it, including the pistol with which his father had killed himself. Ernest was terribly upset.

—John Dos Passos, the Art of Fiction No. 44, Spring 1969

When Hemingway and Dos Passos—who was born on this day in 1896—went to Spain during the civil war, they were close friends, though it was an odd, uneasy match. They’d met in Paris, but their personalities couldn’t have been more opposed: reticent Dos Passos didn’t go in for the Hemingway model of chest-thumping virility. And anyway, Hemingway had already maligned Dos Passos once in print, implying in A Moveable Feast that he was a slippery, duplicitous “pilot fish.” Dos Passos didn’t hold a grudge, apparently; even in his Art of Fiction interview, he said only that A Moveable Feast is “a little sour.”

Dos Passos was a much more overtly political writer than Hemingway, and when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, he was at the apex of his popularity, having appeared on the cover of Time to commemorate his new novel, The Big Money, the third installment of his U.S.A. trilogy. That meant he was, for the first and last time, on equal footing with Hemingway, which can’t have sat well with the latter.

Both writers were moved to action by their support for the Loyalist government, and so both embarked for Spain, Hemingway having contracted to write dispatches for a newspaper and Dos Passos having agreed to help with a documentary about the war.

What happened next is murky. Dos Passos arrived in the spring of 1937 expecting to meet an old friend of his, José Robles. As George Packer explained in a 2005 piece for The New Yorker,

José Robles was a left-wing aristocrat … [but] maintained enough independence of mind to raise an alarm among pro-Communist Spanish authorities and the Soviet intelligence agents who, by early 1937, were bringing the government increasingly under Stalin’s control. Dos Passos was counting on Robles to serve as his main Spanish contact on the film; but by the time the two American novelists reached Madrid, separately, Robles had disappeared. It was Hemingway who learned first … that Robles had been arrested and shot as a Fascist spy. To this day, the manner and motive of Robles’s death remain a mystery…

Hemingway broke the news to his friend, but apparently he was impolitic about it—and so began their falling out, with Dos Passos vouching for Robles and Hemingway laughing at his naïveté.

Dos Passos’s response to his friend’s disappearance reflected his sense that progressive politics without human decency is a sham. Hemingway, in a thinly disguised magazine article about the episode published in a short-lived Esquire spinoff called Ken, described these scruples as “the good hearted naiveté of a typical American liberal attitude.” Bookish, balding, tall and ungainly, sunny in temperament, too trusting of others’ good will: Dos Passos was the sort of man who aroused Hemingway’s sadistic appetite. “White as the under half of an unsold flounder at 11 o’clock in the morning just before the fish market shuts” was one of Hemingway’s fictionalized descriptions of his old friend.

Dos Passos mentions none of this in his Art of Fiction interview—there are only those pleasant recollections of the pair reciting the Bible to each other. He was too disillusioned to write about it, meaning that Hemingway’s accounts came, by virtue of repetition, to seem real.

If you’re curious about their friendship, and what Spain did to it, check out Stephen Koch’s The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of José Robles.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

Think Big

Image via Wikimedia Commons

We are told it is a liability to be thin-skinned, and it’s true that these are bad times for it. When an Internet slight makes you question your path in life, an encounter with a surly stranger results in canceled plans, and the day’s news derails your day, you are at the whims of fortune. And a life without perspective, like a painting, is disorienting.

But the porousness goes both ways, doesn’t it? And if everything looms large, the world’s kindnesses are equally outsized, like in that store Think Big, which only carried enormous versions of things. Maybe you didn’t want a giant jar of mustard. But the fact that it existed meant that you could also have a six-foot Dixon Ticonderoga No. 2, so.

Today I had a truly wonderful airport experience. The trip to the terminal was quick and pleasant. My neighbors and I were routed into the expedited security line and so were able to retain our shoes and sweaters. The Transportation Security Administration officers were jolly and kind, too. And at one moment a woman in a pair of very low-riding jeans bent over, exposing a vast plumber’s crack. Out of her earshot, the TSA man said to me, “Full moon tonight!” as he checked over my ID.

Then came all the usual pleasures of an airport: I bought a newspaper and a pack of an intriguing new gum—and the selection was excellent! I slathered myself in samples of Crème de la Mer. The coffee at the Dunkin’ Donuts was strong and hot, and the cruller unusually fresh.

But most wonderful of all: when we boarded the plane, it was to find that it was not full to capacity. And as the doors closed, I saw that I was to have a row of three seats to myself. I am not lying when I say that tears of gratitude came to my eyes. It was a pure happiness. I lay down with my head on my tote bag and my coat over my legs and everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow. And I said to myself, over and over, It’s worth it, it’s worth it.

Updike: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Fan

“I can’t remember the moment when I fell in love with cartoons, I was so young,” John Updike once recalled in Hogan’s Alley magazine. “I still have a Donald Duck book, on oilclothy paper in big-print format, and remember a smaller, cardboard-covered book based on the animated cartoon Three Little Pigs. It was the intense stylization of those images, with their finely brushed outlines and their rounded and buttony furniture and their faces so curiously amalgamated of human and animal elements, that drew me in, into a world where I, child though I was, loomed as a king, and where my parents and other grownups were strangers.”

This is one of many passages where Updike talks about his childhood love of comics, a theme that recurs not just in essays but also in poems and short stories. What deserves attention in this passage is not only what Updike is saying but the textured and sensual language he’s using when he recalls the “oilclothy paper” and the “buttony furniture.” His tingling prose, where every idea and emotion is rooted in sensory experience, owes much to such modern masters as Joyce, Proust, and Nabokov, but it was also sparked by the cartoon images he saw in childhood, which trained his eyes to see visual forms as aesthetically pleasing. Indeed, the comparison with Nabokov is instructive since the Russian-born author of Lolita was also a cartoon fan. The critic Clarence Brown has coined the term bedesque (roughly translated as “comic strip-influenced”) to describe the cartoony quality of Nabokov’s fiction, including its antic loopiness, its quicksilver movement from scene to scene, and its visual intensity. I think one reason Updike felt an affinity for Nabokov is because they both wrote bedesque prose.

The origins of creativity is a riddle that can never be solved; yet if we love an artist, we want to find clues to the secret source of his or her gifts. Literary biography—an enterprise Updike regarded with some skepticism—is largely a hunt for such deeply buried evidence. As an aid to future biographers and anyone else interested in pursuing the mystery of Updike’s prodigious talent, I’d suggest paying attention to his lifelong love affair with cartooning, a passion that burned hottest when he was young but remained warm until his dying days, when he ceased to draw but still repeatedly referred to the comics he had loved in childhood.

The outlines of the story are clear enough. Before he could read, Updike was enamored by the anthropomorphic kingdom of talking rodents and fowls presided over by Walt Disney, enjoying both the moving Mickey Mouse seen on the silver screen and the still Mickey found in Big Little Books and newspaper funnies. This passion for all things Disney fed early ambitions of being an animator. Updike’s interest soon spread to all the other characters found in the newspaper funnies section, and he was regularly following strips like Barney Google, Captain Easy, Terry and the Pirates, Alley Oop, Little Orphan Annie, Li’l Abner, and many others.

Branching out from comic strips and animation, the young Updike also developed a taste for comic books, a new form of pop-culture ephemera that mushroomed in popularity in the 1930s and that initially reprinted old strips but soon offered vibrant four-color fantasies featuring masked vigilantes and superbeings like Batman, Wonder Woman, and Superman. Updike’s taste ran toward the more humorous of the superheroes rather than the more earnest examples of the genre: C.C. Beck’s Captain Marvel, Jack Cole’s impossibly stretchy Plastic Man, and Will Eisner’s masked avenger the Spirit.

On the cusp of adolescence, Updike’s cartooning fervor intensified when he discovered the single-panel gag cartoons found in magazines like Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post. When he was twelve, his Aunt Mary bought his family a subscription to The New Yorker, which quickly became the most important magazine for Updike, as he yearned to appear in its sophisticated pages. Although he would go on to become the preeminent New Yorker writer, he was at first far more interested in the drawings by Thurber and Steinberg than in the magazine’s acres of prose.

The teenage Updike mailed off a steady stream of cartoons in the hopes of breaking into the visual-humor market. He would continue cartooning as an undergraduate at Harvard, where he sprinkled the pages of the Lampoon with his drawings, but Updike’s undergraduate years also marked the end of his cartooning career and his transformation into a writer. He felt that the other artists at the Lampoon were simply much more talented than he was, and he’d also discovered his facility for light verse and narrative prose. It could be that Updike was too harsh on his early cartoons. The samples reprinted in his collection More Matter (1999) display a memorably jagged bluntness that calls to mind the work of Virgil Partch, who was on the cutting edge of the stylistic revolution of the forties and fifties that opened up cartooning to energetically angular, poking shapes. In any case, Updike’s past as wannabe cartoonist has left many residual traces on his work, like little flecks of ink that get caught in an illustrator’s fingernail. “One can continue to cartoon, in a way, with words,” he noted. “For whatever crispness and animation my writing has I give some credit to the cartoonist manqué.”

The connection between Updike’s drawing and writing is evidenced, too, by the letters he sent off to newspapers and cartoonists. When he was nine or ten, the local newspaper stopped carrying the Mickey Mouse comic strip, provoking the future novelist to write an indignant protest letter. That missive was the first in a long string of comics-inspired correspondence that included his beseeching inquiries to cartoonists asking for original art. “Our acquaintance was slight but long,” Updike recalled of his affection for Steinberg:

In 1945 I wrote him from my small town in Pennsylvania asking that he send me, for no reason except that I wanted it, the original of a drawing I had seen in The New Yorker, of one man tipping his hat and another tipping back his hat with his head still in it. At this time I was an avariciously hopeful would-be cartoonist of 12 or 13 and Steinberg a 31-year-old Romanian Jew whose long American sojourn had begun but four years before. Perhaps he thought that his new citizenship entailed responding to the importunities from unknown American adolescents. He sent me not the original but a duplicate he had considerately made, with his unhesitant pen, and inscribed it, in impeccable New World Fashion, “To John Updike with best wishes.”

As with Nabokov, Updike found in Steinberg an unexpected kindred spirit, someone who taught the American-born writer to see his native land with foreign eyes. Steinberg, when Updike wrote to him, was in the midst of instigating a stylistic revolution at The New Yorker. While artists such as Otto Soglow and James Thurber had already expanded the stylistic range of magazine cartooning by bringing in starkly simple and expressive drawings, Steinberg took this newfound liberty a step further by doing cartoons that avoided easily understood gags based on social humor and instead offered elliptical comments on the American visual landscape. In Steinberg’s cartoons, the line between words and pictures disappeared as he drew glyphs and signs that conveyed human passions. Appropriating images from advertising and popular entertainment while giving them a satirical tweak, Steinberg in the 1940s anticipated everything from the paintings of Andy Warhol to the experimental fiction of Donald Barthelme. Steinberg also prefigured the future attempts of his fan John Updike to write poems and stories that mashed up words and images, as in “Mid-Point” or “The Invention of the Horse Collar.”

Aside from the Steinberg drawing, Updike solicited “treasures” from other artists. In a letter to me, he mentioned that his dispatches to cartoonists earned him “an Otto Soglow Little King, and a Thurber dog he drew for me when he was all but blind. Also I have a Barnaby strip with the pasted-on lettering falling off, and half of a ‘Sunday Mickey Finn.’ I must have had 20 or more in my prime.” Luckily enough, at least two of the letters the adolescent Updike wrote still survive.

On September 6, 1947, Updike wrote to Milton Caniff, then among the most famous cartoonist in America for his two major strips, Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. Terry and the Pirates was one of the great comic strips of the thirties and forties: it had action, lovely ink-rich noir art, a winsome young hero who matures during the course of his adventures, an exciting Asian backdrop (which in the late thirties became timely and even urgent), and sexy femme fatales (most prominently the famed Dragon Lady). In 1946, Caniff left Terry and started a new strip, Steve Canyon, a move that caught the attention of comic strip fans all over the nation. John Updike, then fifteen and living in his mother’s ancestral farm in Plowville, Pennsylvania, was one such Caniff follower and used the fact that Caniff was in the news to entice him to send some original art.

Updike began his letter, “For a long time, I was under the impression that Terry and the Pirates was the best comic strip in the United States. Imagine my dismay, then, when I heard that its creator, its mastermind, was going to desert Terry, leave it in the lurch, and wander off to some new interest, called Steve Canyon. Apprehensively I subscribed to the paper that carried Steve Canyon and waited for the results. It didn’t take me long to discover that Steve Canyon was now the best comics strip in the United States. Obvious conclusion: Milton Caniff is the best cartoonist in the world.” The charm of this letter is inseparable from the exuberantly adolescent longings that course through it. Already a fluid writer, Updike manages to be brassy even as he lays on the flattery in an obviously obsequious manner. Part of the tone of the letter owes something to the very cartoonist Updike was praising, since Caniff’s dialogue tended toward wise-guy knowingness.

Updike never forgot Caniff. In his last novel, The Widows of Eastwick, a trip to China includes a description of the country’s history in the early twentieth century that shows the author was still mindful of Terry and the Pirates: it is a land of “Pearl Buck peasants, dragon ladies, rickshaws, and comic-strip pirates.” What started as a fannish passion became part of Updike’s mental furniture till the end of his life.

A few months after writing to Caniff, Updike sent some equally enthusiastic fan mail to Harold Gray, creator of Little Orphan Annie. A Dickensian melodrama about a poor orphan named Annie who struggles against an oppressive society while being intermittently aided by her guardian, “Daddy” Warbucks, Gray’s strip was notable for its strident right-wing politics. In Gray’s universe, the bad guys were invariably do-gooding reformers, union bosses, pointy-headed academics, and other liberal types while the heroes were he-man entrepreneurs. I’d guess that in growing up in a household that cherished Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, Updike would have had little use for Gray’s politics, but his love of cartooning transcended any ideological litmus test. Dated January 2, 1948, Updike’s letter to Gray contains a marvelously confident and crisp account of Little Orphan Annie’s blustery melodramatic universe. “Your villains are completely black and Annie and crew are perfect, which is as it should be,” he wrote. “One of my happiest moments was spent in gloating over some hideous child (I forget his name) who had been annoying Annie toppled into the wet cement of a dam being constructed.” This is an extremely astute bit of criticism. As in traditional melodrama, Gray orchestrated his audience’s indignation by showing his heroine constantly suffering at the hands of self-satisfied brutes. The moments when these villains get their comeuppance are always a highlight. Yet while much has been written about the strip by journalists and academics, few have gotten to its emotional core with as much insight as the teenage Updike.

Updike’s future career as a part-time art critic can also be seen in the authoritative way he describes Gray’s art. “Your draughtmanship is beyond reproach,” he wrote. “The facial features, the big, blunt fingered hands, the way you handle light and shadows are all excellently done. Even the talk balloons are good, the lettering small and clean, the margins wide, and the connection between the speaker and his remark wiggles a little, all of which, to my eye, is as artistic as you can get.” Updike’s attention to details such as Gray’s portrayal of hands or his distinct lettering style bespeaks the eyes of a fellow craftsman. The cartoonist Chester Brown once told me he loved Gray’s expressive use of hands. He was surprised when I told him that John Updike had also taken note of the same aspect of Gray’s art.

Updike’s poems, short stories, and novels are rich in cartooning allusions. His sensual prose—which was arguably nonpareil in its responsiveness to the visual world—owed something to the long hours he spent pouring over cartoons and learning to draw. But what exactly did Updike mean when he wrote that “one can continue to cartoon, in a way, with words”? I’ve often talked about Updike with my friend Chris Ware. Like me, Chris is an Updike addict. He once told me that he felt Updike’s attempts to cartoon with words can be most effectively seen in the Maple and Bech stories. Although both these story cycles deal with very adult subjects—notably adultery and divorce—they are often written in a bright, chipper, affectionate tone that evokes classic cartooning.

The critic William H. Pritchard notes that the first Bech book was written with a “comic lightness and brio” that distinguished it from some of Updike’s weightier fiction of the sixties. Pritchard takes note of a sentence from the story “Bech Panics” where the hero goes to a hotel for an unsuccessful assignation with a lover:

But the overflowing meal at the boorish roadside restaurant, and their furtive decelerated glide through the crackling gravel courtyard of the motel (where a Kiwanis banquet was in progress, and had hogged all the parking spaces), and his fumbly rush to open the tricky aluminoid lock-knob of his door and to stuff his illicit guest out of sight, and the macabre interior of oak-imitating wallboard and framed big-pastels that embowered them proved in sum withering to Bech’s potency.

Pritchard rightly sees Nabokov as a source for the adjectival mirth of this passage (“boorish” and “aluminoid”), but behind the Russian master there is also Updike’s love of cartooning with words. What makes this passage cartoony is the playfulness of tone, achieved by Updike’s attention to surface visual details (“crackling gravel courtyard”) keeping comically incongruous company with diction that runs from the excessively abstract (“furtive decelerated glide”) to the implausibly poetic (“embowered,” which echoes Milton’s account of Adam and Eve in Paradise). When he wanted to, Updike could write with clear-glass transparency, but in a sentence like this one, he is writing gleefully attention-getting prose, as stylized and artificial as the comic strips he loved. It’s no accident that the covers of the Bech books all contain caricatures of the hero done by one of Updike’s favorite cartoonists, Arnold Roth. Nor is it surprising that in “Bech Noir” the writer takes on a superhero identity, becoming a kind of literary Batman avenging writers who have been mistreated by critics. Bech as Batman even has a sidekick named Robin, an eventual lover and spouse.

A full inventory of the impact of cartooning on Updike’s writing would require a much longer essay. It would include a discussion of a poem that features Al Capp (creator of L’il Abner); Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom’s resentful affection for the girlie comic strip Apartment 3-G; the superhero references in the later Rabbit books; the story “Intermission,” about a young writer of comic strips; the novel Marry Me, which features a character who works in advertising animation; and the essays Updike devoted to cartoonists such as Ralph Barton, James Thurber, and Charles Schulz. Such a discussion would also look more deeply at the visual potency of Updike’s prose and also his habit of limning vividly grotesque secondary characters (think for example of the story “The Madman”), a fictional practice that owes as much to the tradition of caricature as to the model of Dickens.

Updike stopped cartooning while he was an undergraduate at Harvard. This is a factually true statement, but it ignores a larger reality. While Updike might have ceased cartooning, the visual language of comics was never far from his mind. Cartooning was an inextricable strand in his creative DNA.

Jeet Heer is a Canadian cultural critic and the author of two books: Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays, & Profiles , from which this essay is adapted, and In Love with Art: Françoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman .

Say “I Love You” with Vintage Issues of The Paris Review

It’s hard to put love into words. That’s why so many of us express our emotions with small, high-pitched noises, like woodland creatures.

But Valentine’s Day is only a month off, and we must rise to the occasion with language. Luckily, The Paris Review’s archive is full of writers—more than sixty years’ worth—who know all the right things to say.

That’s why we’re offering a special Valentine’s Day box set: you choose any three issues from our archive, and at no extra charge, we’ll package them in a beautiful gift box, including a card featuring William Pène du Bois’s 1953 sketch of the Place de la Concorde. (You may have seen it on the title page of the quarterly, or in the footer of our Web site.) Then they go straight to the home of your significant other.

Unless you’d rather send them to yourself, so you can memorize, say, the entirety of our Art of Poetry interview with Pablo Neruda and impress your valentine by quoting it at length. Either way, you look very thoughtful.

You’ll find all the details here—orders begin shipping the last week of January.

The Bleared White Visage of a Sunless Winter Day, and Other News

Karl Hagemeister, Havelufer mit Kahn im Schneetreiben, 1895.

Which Thomas Hardy novel is the bleakest? A data-driven study looks at such criteria as “bleak events” (unrequited love, grinding poverty, animal genitalia-related injury), “bleakest words” (poor, alone, dead), and “bleakest quotes” (“The bleared white visage of a sunless winter day emerged like a dead-born child”).

Let’s keep things bleak and remind ourselves that the Internet isn’t killing the culture—it’s always been next to impossible to make a living in the arts. “‘You can make a killing in the theatre, but not a living,’ the playwright Robert Anderson is reported to have said in the mid-1950s—at the height, in other words, of government intervention and middlebrow respect for art.”

Bleaker still: “ ‘Brand’ may be an ugly word when applied to an author, literary agent Jonny Geller acknowledged, but it is only a shorthand for a way in which publishers are attempting to hold on to the reading public at a time when sales of print books are flat and electronic gadgets vie for readers’ attention.”

Because we’ve got a theme going, let’s investigate the history of influenza. “Some medical historians say that the virus goes back even further than the sixteenth century and into antiquity. They point to a suspiciously flu-like illness mentioned in writings dating as far back as 412 B.C. Reports of ‘a certain evil and unheard of cough’ spreading through Europe in December 1173 cause some to believe flu pandemics have been around since the Middle Ages.”

And just to send it on home, it’s time to learn about anthropodermic bibliopegy, the art of making books from skin. For instance, “Burke and Hare were two serial killers in the early nineteenth century. They killed seventeen people. Essentially they were posing as body snatchers, but actually they were just killing everybody and selling the bodies to anatomists for dissection. So they’re caught, and Hare turns King’s evidence and Burke goes down for the crime. As added punishment, he is publicly dissected … They also took his skin and created all of these objects from it. One of the objects is a pocketbook.”

January 13, 2015

Bring Up the Bodies

Photo: Golden Globes

Last night—or early this morning, I guess, around four A.M.—I woke up from a dream. I’d been reading a Hilary Mantel novel and watching red-carpet recaps before bed, and the two apparently melded in my brain in the most literal way imaginable. In my dreams, Thomas Cromwell attended the Golden Globes. Or Mantel chronicled them. I’m not sure which—but this is how it went down.

It is the awards season. Lupita in silks and nosegays, Felicity stately in Dior. Photographers line the strip of crimson worsted like so many starlings on a line: here a Michael Kors, here a Givenchy. Lacquered hosts prattle now of jewels, now with furrowed brow of news from abroad.

“Alchemy,” says George Clooney, boyish and urbane. He is at his ease, of a mind to talk of brass rings and love.

Kevin Spacey is at the podium, eyes narrowed in a mockery of evil, bent on revenge. Jeremy Renner stands at his ease and leers, “You’ve got the globes, too.”

Virgins win, and Birdmen.

Cromwell stands with the others and prices the finery, an old habit not easily lost.

“There was a time,” he says, “when the carpets were not ruled by the stylists. There was Marlee Matlin then, and Bonham-Carter. We knew risk then, and yes, folly, too. I saw once a woman dressed in the plumage of a swan.”

And around him, etched in jewels, he sees the motto: “Je suis Charlie,” they say. “I stand with France.”

You Get What You Deserve

Sir Thomas Wyatt’s “They Flee From Me” and the history of the word deserve.

Angelica Kauffmann, Ariadne Abandoned by Theseus, 1774

The best I-just-got-dumped pop song ever, beating out such classics as “Wild World,” “Don’t You Want Me,” “Nothing Compares 2 U,” “You Oughta Know,” and “Irreplaceable,” is six hundred years old: Sir Tom’s “Runaway,” known to poets and scholars as “They Flee From Me” by Thomas Wyatt. You can read the original lyrics here (old spelling, modern spelling), but the structure and arc couldn’t be simpler: three verses, no chorus.

Wait, what? They used to come running after me.

Especially this one girl. Man, she was so hot.

It’s true. Now she won’t even talk to me. I must have been too nice.

At least she’ll get her comeuppance: “But since that I so kindly am served / I would fain know what she hath deserved.”

To paraphrase: since she was so nice to me (sarcastic!)—and/or the now-obsolete meaning: since she treated me so in keeping with her kind, just the way you’d expect her to act (that bitch!)—I’d like to know what she has coming. The strange word to modern ears is the last one. Doesn’t the singer already know what she deserves, just not what she’s going to get?

What it means to deserve has changed in six hundred years. The prefix de-, from Latin, not only means down or down from (descend, decline, derail) but down to the bottom, thoroughly, completely. To declaim is to shout away, declare is make perfectly clear, denude is strip totally bare, despoil is ruin utterly. To deserve is to serve zealously and meritoriously, thus to merit by service. In the original meaning, now obsolete, deserve means to acquire or earn a rightful claim by virtue of actions or qualities; now it means to have already acquired it. Wyatt was curious what his ex-girlfriend had earned by her behavior.

To earn (from the German ernten, to harvest) is to labor, specifically farm labor: reaping, threshing, sowing. To earn means to work, and as a result to obtain or deserve a reward of money, praise, or advantage. The doubling and difference of the two words is typical of English vocabulary, in a pattern dating back to the Norman Conquest: Germanic words are agricultural, peasant, blunt, while French or Latinate words are courtly and fancy. Mother and father vs. maternity and paternity, work vs. employment, king vs. royal majesty, “Can I help” vs. “May I be of assistance.” One kind of person tends cows, pigs, sheep, and deer, the other eats beef, pork, mutton, and venison.

Manual labor and courtly service used to be parallel in English—to deserve was to earn by good service; to earn was to work hard and deserve a reward. But the courtly sense shifted. Now to deserve something means you’ve already earned it: it’s owed to you even if you don’t do any more work than you already have (or haven’t!). Upper-class prosperity is self-perpetuating: if you have capital already, it’ll pay out interest on its own. There are no unjust deserts in English, because deserts are what you deserved/earned in the old sense, what you deserve in the new sense. (Dessert, incidentally, has two s’s because it’s from dis-serve, to clear the table.)

Other languages don’t share this idea of what’s fair. In German, earn and deserve are the same word: verdienen (from dienen, to serve; a Diener is a servant, Dienst is service). This is often a translation puzzle: How should verdienen be translated in any given case? You can get what you deserve in German, too—Er bekommt was er verdient—but then you’re also always getting what you earned through your hard work. Faith that the system functions properly is built into the language. It makes my head spin to imagine what our culture would be like if we always earned what we deserve and deserved what we earn.

In French, meanwhile, deserve is mériter, to merit, while earn is gagner: to gain, to win, whether a game of skill or a crapshoot. Deserts are just but gains are ill-gotten—earning, in the French language, is separate from merit. This is a cynical view, fit for Balzacian strivers and misers, or philosophers who think that everything is about power: what you have coming to you is what you’ve gotten your hands on, by hook or by crook. In German, all earnings are deserved; in French none are.

In English, you get what you deserve, if you’re rich. At least we all reap what we sow.

Damion Searls, the Daily’s language columnist, is a translator from German, French, Norwegian, and Dutch.

Dear Critics: You Heard It Here First

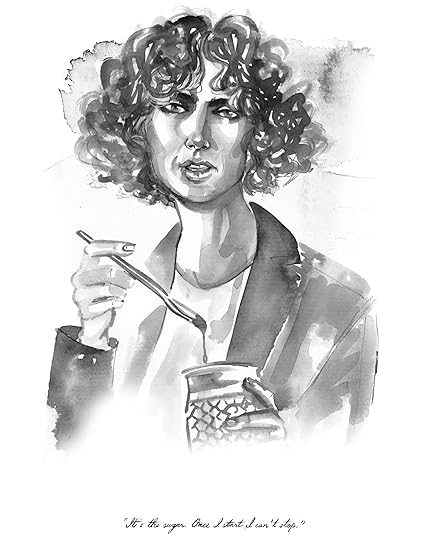

Illustration: Samantha Hahn

Although Rachel Cusk’s Outline has not been available in hardcover until today, it’s already enjoyed a wild succès d’estime with some of our favorite critics. Last Wednesday, in the New York Times, Dwight Garner called it “transfixing … You find yourself pulling the novel closer to your face, as if it were a thriller and the hero were dangling over a snake pit.” In The New Yorker, Elaine Blair used Outline as the occasion for a trenchant essay on fiction and autobiography:

The novel is mesmerizing; it marks a sharp break from the conventional style of Cusk’s previous work … Cusk’s insight in Outline is that, instead of trying to show two sides of a marriage, she might do the opposite: focus on the inevitable, treacherous one-sidedness of any single account [which] surely has something to do with why marriages themselves come apart.

In the Guardian, Hilary Mantel described Outline as “fascinating, both on the surface and in its depths.” Bookforum’s Hannah Tennant-Moore called it “lovely … smart, ascetic”; and in the most recent New York Times Book Review Heidi Julavits raved: “Spend much time with this novel and you’ll become convinced [Cusk] is one of the smartest writers alive.”

None of this will come as news to readers of The Paris Review—because, starting with our Winter 2013 issue, we published Outline in its entirety, with exclusive illustrations by Samantha Hahn. Here’s a slide show to celebrate the U.S. hardcover publication, and to remind our colleagues in the reviewing business where they can find the most transfixing, mesmerizing, fascinating, lovely fiction of 2016.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers