The Paris Review's Blog, page 624

January 21, 2015

More Things in Heaven and Earth

Photo: Ben Salter, 2006, via Flickr

On this date in 1976, the Concorde started flying commercial passengers on London-Bahrain and Paris-Rio routes. For the next twenty-seven years, this fleet of turbojets would ferry the rich and famous betwixt glamorous world hubs with unprecedented speed and luxury. And when the Concorde ended its reign, following a 2000 crash and a global post-9/11 flying slump, it was regarded as the end of an era.

For many—particularly anyone in its flight path—this was a relief. And since its inception, critics had regarded the gas-guzzling fleet as indefensible. In perhaps the ultimate eighties quote, Linda Evangelista declared, “If they had Nautilus on the Concorde, I would work out all the time.” It’s probably this tinge of decadence that’s burnished Concorde’s image in the years since its end. The tenth anniversary in 2013 spawned tributes and slideshows, images of spa-food menus and full bars, memories of the jet-setting clientele and the monogrammed napkins and crockery that these jet-setters famously stole as souvenirs. (Well, Andy Warhol anyway.)

When I was younger, I was fascinated by the notion of the Concorde. It felt sort of mythical, or at least out of a Deco-era fantasy of the future: a special rich-person plane that seemingly defied the laws of the universe to buy them more time. And I was obsessed by the idea of rich people, who presumably could buy whatever they liked, pocketing salt shakers. Somehow Concorde always blended together in my child’s mind with a sort of blithe amorality.

I knew I’d never get to fly Concorde, and I didn’t even want to. As it was, the six-hour passage between continents felt barely sufficient to contain a shift between cultures and mind-sets; it never felt as though we had earned it. And wasn’t time just as good in the air? Well, I didn’t have a job yet. (As you might infer, I was also terrible at physics.)

If you chose to take a longer view, the end of the Concorde was exciting, in a strange way. We expect progress, now; technological backsliding is rare enough to constitute a novelty. We take our pleasures where we can find them.

Before piloting the final flight out of Heathrow, captain Mike Bannister told reporters, “From today, the world is a bigger place.” Read out of context, that sounds optimistic.

Concorde retired its last flight when I happened to be in London. The friend with whom we stayed was an older lady who lived not far from Heathrow, and was thrilled to know she’d no longer be bothered by the regular roar of what she referred to as “audibly burning money.” She had once had a chance to ride it, when someone was dying in the late seventies, but hadn’t. It’s funny how sometimes an old person will tell a story about something almost happening with the same satisfaction as if it actually had. It’s a different idea of what constitutes the point of a story.

The First American Novel

The Power of Sympathy turns 226.

The first-edition title page of The Power of Sympathy.

William Hill Brown’s The Power of Sympathy: or, The Triumph of Nature was published 226 years ago today, in 1789. It’s generally considered the first American novel, though you won’t find it on many (any?) short lists for the Great American Novel. To speak with the kind of prudence it so sternly advocates: the passing centuries have hidden its charms.

An epistolary novel in the style of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, The Power of Sympathy tells the story of Thomas Harrington, a New Englander who has fallen, against his father’s wishes, for a woman named Harriot. He dearly yearns for Harriot as his mistress: “Shall we not,” he asks her, “obey the dictates of nature, rather than confine ourselves to the forced, unnatural rules of—and—and shall the halcyon days of youth slip through our fingers unenjoyed?” (Actually, Harrington says all of this with “the language of the eyes.” Early Americans excelled, you see, at conducting complicated conversations using only their peepers.)

Thomas’s friend Worthy urges him to marry the girl, rather than simply miring himself in licentiousness, and so the pair fall deeply in love; they’re soon engaged. But Thomas’s father does not receive the news well, and for good reason: Harriot is his illegitimate daughter, and now the secret must come out to protect his son’s honor. “He is now even upon the point of marrying—shall I proceed!—of marrying his Sister!” the father writes. “I fly to prevent incest!”

Maybe had he flown earlier, instead of pausing to write a letter to his minister about it, things would’ve turned out differently—we’ll never know. In any case, the lovers are understandably distraught, on the eve of their wedding day, to learn of their unwitting incest. They terminate the betrothal posthaste. Harriot, laid low by grief, succumbs to consumption, but not before unburdening herself thus:

How fleeting have been the days … when anticipation threw open the gates of happiness, and we vainly contemplated the approach of bliss … when we beheld in the magick mirrour of futurity, the lively group of loves that sport in the train of joy. We observed in transports of delight the dear delusion, and saw them, as it were, in bodily form pass in review before us … We were happy in idea, nor was the reality far behind. And why is the vision vanished ? O ! I sink, I die, when I reflect—when I find in my Harrington a brother—I am penetrated with inexpressible grief—I experience uncommon sensations—I start with horrour at the idea of incest—of ruin—of perdition.

She dies.

Disconsolate, Thomas decides “to quit this life” and—after about a dozen letters to Worthy saying he’s really going to do it any day now, the pain is unendurable, life is just a maze of suffering and he’s really quite lost in it, et cetera, et cetera—he shoots himself. He’s found “wheltering in his blood” with a copy of The Sorrows of Young Werther at his side.

The Power of Sympathy is a sentimental novel in the strictest sense of the term: a kind of humanistic endeavor to evoke emotions in readers, giving them models on which to base their own emotional lives. It was crucial, in the second half of the eighteenth century, to allow yourself to be whipped into an emotional lather—showing your feelings was a mark of character.

By that standard, and perhaps that standard alone, The Power of Sympathy is full of character. Critics have read it as an allegory of the nascent United States, helping to reinforce the caution and virtue that would best serve the young nation. Certainly it wears its heart on its sleeve—its preface reads, “Intended to represent the specious causes, and to Expose the fatal CONSEQUENCES, of SEDUCTION; To inspire the Female Mind With a Principle of Self Complacency, and to Promote the Economy of Human Life.” It’s important to sympathize, the novel tells us—but be rational about it.

In part, though, Brown must have aimed to titillate. He published the novel anonymously—a curious choice, since his only supposed ambition was moral didacticism. And it surely was a great thrill for his readers to find themselves in such proximity to incest, that taboo of taboos. To add to the sex appeal, Sympathy was “based on true events,” as a film adaptation might say: around the same time, two of Brown’s neighbors had been embroiled in a nearly identical scandal.

Still, Sympathy fascinates because it’s so purely the product of a historical moment: in 1789, literacy was on the rise and the business of publishing, especially newspaper publishing, was coming into its own. Letter writing was increasingly popular—the medium of the written word felt more democratic than ever before. The country was new and hungry for stories about itself; what we think of as the American character had yet to be minted. Beneath Sympathy’s many layers of mawkishness, there are some uniquely American details—lavish descriptions of the Rhode Island (“Rhodeisland”) greenery, for instance, and a surprisingly frank discussion of the South’s culture of slavery.

Mainly, though, it’s full of lines like these:

How opposite are the pursuits and rewards of her who participates in every rational enjoyment of life, without mixing in those scenes of indiscretion which give pain on recollection!—Whose chymical genius leads her to extract the poison from the most luxuriant flowers, and to draw honey even from the weeds of society. She mixes with the world seemingly indiscriminately—and because she would secure to herself that satisfaction which arises from a consciousness of acting right, she views her conduct with an eye of scrutiny. Though her temper is free and unrestrained, her heart is previously secured by the precepts of prudence—for prudence is but another name for virtue. Her manners are unruffled, and her disposition calm, temperate and dispassionate, however she may be surrounded by the temptations of the world. Adieu!

Adieu, indeed.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

An Exciting Career in Forensic Sculpting, and Other News

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Skull, ca. 1900.

“They lost their identity … We’re going to give it back to them.” In which the New York City medical examiner’s office teams up with fine art students in a last-ditch effort to ID crime victims: “Each student was given a skull—a replica made by the medical examiner’s office of each victim—and a block of clay to sculpt a face. The students were told to incorporate whatever information investigators recorded in finding and examining the skeleton, including estimates of the victim’s age and height, maybe a hair type or style, and possible clothing sizes.” (Listen to the sound of hundreds of television executives thinking, Could this be our next big crime series?)

Leslie Jamison on the enigma of natural beauty in Whitman’s Specimen Days: “Part of our pleasure in reading his book … is not just feeling close to his sensory perceptions, but feeling invited more deeply into our own—to feel the world more fully in all its snorting ice and malachite cabbages and whirling locusts and wriggling worms.”

In the thirties, a Grade A swinging-dick asshole named Harry Anslinger took over the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, then on the verge of being dissolved. So he set himself a reasonable goal: lock away Billie Holiday for drug abuse. Jazz to him sounded “like the jungles in the dead of night.” His agents wrote that “many among the jazzmen think they are playing magnificently when under the influence of marihuana but they are actually becoming hopelessly confused and playing horribly.”

In sci-fi, where exactly do the science and fiction collide? “Science writing isn’t the same as fiction writing. Sometimes people who read popular science about scientific theories like loop quantum gravity say ‘it’s like reading science fiction.’ But no, it isn’t.”

Painting and boozing in Belgium: Two years after Waterloo, J. M. W. Turner “visited the Belgian battlefield where the Brits, Prussians, Dutch and Belgians finally put paid to Napoleon’s dreams of empire. The resulting painting, an unnerving clash between dark, roiling clouds and corpses illuminated by the torches of the bereaved, is no paean to victory … What does a thirsty man—which Turner was, by all accounts—drink after a day sketching carnage?”

January 20, 2015

Fleur’s Flair

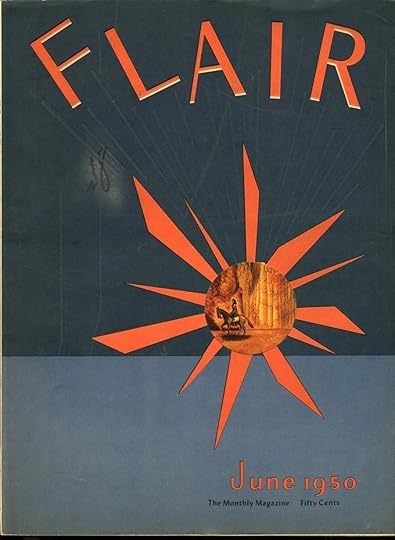

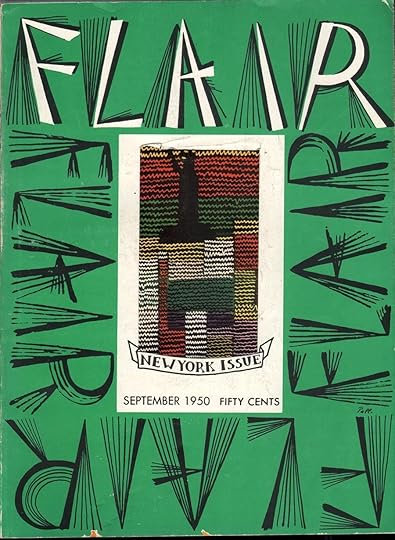

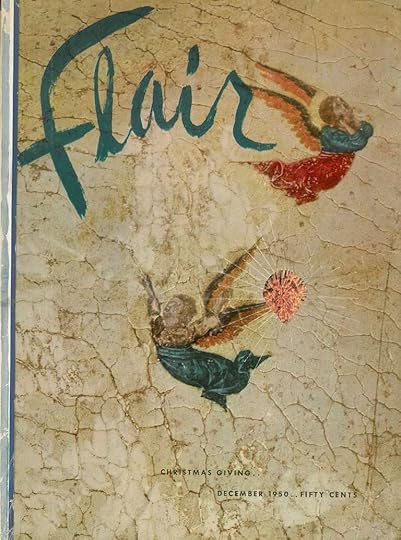

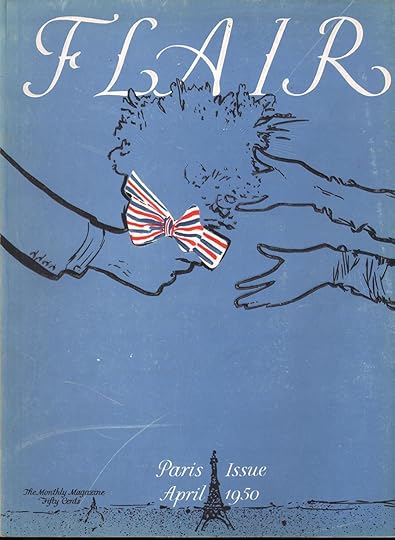

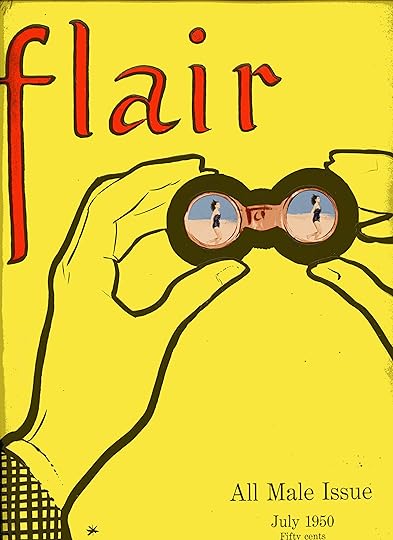

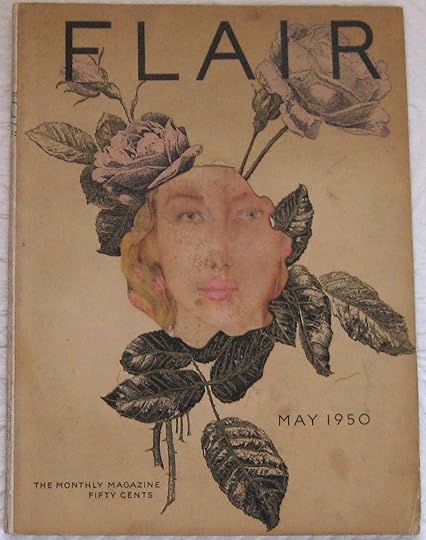

Flair‘s first issue.

Flair Magazine existed for only one year and twelve issues, from February 1950 to January 1951. In that time, it published the likes of Jean Cocteau, Tennessee Williams, Simone de Beauvoir, Gloria Swanson, John O’Hara, Eleanor Roosevelt, Bernard Baruch, Gypsy Rose Lee, the Duchess of Windsor, Lucien Freud, Salvador Dalí, Colette, and Saul Steinberg, among others.

Fleur Cowles—who conceived of the magazine, edited it, and, perhaps most impressive, persuaded her husband to publish it, even when it meant losing his shirt, if not his whole wardrobe—would be 107 today. If that seems like a throwaway detail, bear in mind that she lived until she was 101. It’s maybe best to let her describe her own accomplishments:

Few women have lived more multiple lives than I have: as editor: as that anomaly, an American president’s personal representative, decorated by six governments; as a writer of thirteen books and contributor to six others; as a painter, with fifty-one one-man exhibitions throughout the world; patron of the arts and sciences, irrepressible traveller and, more importantly, friend-gatherer …

Fond as she was of bragging about her gifts as a friend, or even merely as a “friend-gatherer,” her most enduring creation is Flair, a beautiful, high-minded cataclysm of a magazine that incorporated “cutouts, fold-outs, pop-ups, removable reproductions of artworks and a variety of paper stocks of different sizes and textures”:

[Flair] was simply too expensive to produce … When Flair ceased publication, Mr. Cowles, who had financed it, estimated that it had lost $2.5 million … A spring issue featured the rose, a flower Ms. Cowles painted and extolled until her death. The issue was suffused with a rose fragrance, some four decades before scent strips became ubiquitous.

All this comes from Cowles’s New York Times obit, which is a work of art itself: “Fleur Cowles, 101, Is Dead; Friend of the Elite and the Editor of a Magazine for Them.” Take a step back and you can see the splotch of animus on that headline—“a Magazine for Them.” That’s what Flair was: their magazine. Never yours. It was designed to appear tantalizingly out of reach. That’s a commonplace these days, when every publication aspires to be “aspirational,” but Flair, with its peephole covers and almost farcically high production values, may have done more to further the concept than any other American magazine in history. Copies of The Best of Flair, a 1996 compilation, sold for $250 apiece. And is it any wonder? Just look at the covers:

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

The Not-so-open Road

Hoarding books across the country.

Photo: Frank Kovalchek, via Flickr

Fourteen years ago, my mom bought herself a Volkswagen Jetta, and this Christmas she passed it on to me. My girlfriend Sheena and I did what anyone would: we packed our bags and set a course for Iowa.

What I mean is that we took an old-fashioned road trip, from Minneapolis to San Francisco, and Iowa City was our first port of call. If Sheena and I had set out in the summer we might have shot straight west into South Dakota and beyond, but in winter our rusting station wagon seemed about as likely to make it through the Rockies as to successfully invade Russia. Instead, we drove south through Iowa, Missouri, and Oklahoma, in search of warmer climes and easier roads. People sometimes complain that the Midwest is too flat, but that quality has its consolations. Mountains, like high heels, are attractive but impractical—especially in the snow.

So, Iowa. Of the many things New Yorkers take for granted, the subtlest may be the city’s disproportionate claim to a name it shares with an entire state. You can lop the City off of New York City and people will still know whereof you speak. Iowa City enjoys no such luxury; to most of the world, Iowa is a state and nothing else. Iowa the city—or the City of Iowa City, as the sign reads outside the City of Iowa City City Hall—is best known outside the state to writers, aspiring writers, and anyone watching the current season of Girls. The town is home to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, of course, but it’s also the only UNESCO-designated “City of Literature” in the entire United States. (The UN may have been celebrating the town’s esteemed literary pedigree, or simply acknowledging that, unlike a few other writerly meccas I could name, Iowa City is a place where budding writers can actually afford to live.)

I don’t suppose I’ll ever attend the Writers’ Workshop myself—even if they wanted me, I’ll still be paying off my journalism school loans when my grandchildren win their first Hunger Games—but all the same, Sheena and I thought we might soak in some of the program’s ambient creativity just by passing through town. We forwent a chance to see the world’s largest frying pan in order to reach the town’s premier bookstore, Prairie Lights, before close; afterward, we walked up the street to The Haunted Bookshop, a used bookstore that truly did feel haunted until I found the house cat crashing at intervals from the bookshelves onto an untuned piano.

From these two stores, we walked away with at least ten books. By the end of the week, as we drove south and then west from city to city, that figure would climb to thirty. Thirty books is, of course, more than any two people need in a week, and if I’m being honest most of those books were mine. (Sheena loves a good book as much as the next person, unless that person happens to be her spendthrift bibliophile boyfriend.) But driving hundreds of miles at a time, an act I viscerally associate with the dozens of laps I drove as a younger man between home in Minnesota and college in Ohio, uncorked the forgotten joys of my undergraduate years—chief among them the fantasy that simply buying a book guarantees that it will get read.

In the eight years since I last owned a car, I’ve grown accustomed to a kind of martyrdom in motion—walking my bike up San Francisco’s unforgiving hills, waiting countless hours for the next bus or train, paying fares for the occasional shoeless fellow traveler. In Kyrgyzstan, where I spent a couple years in the Peace Corps, an ambulance running lights and siren once pulled over to pick me up on my way into town. “Don’t worry about this guy,” the driver said, pointing an elbow at a moaning patient in the back. “He’s still got plenty of blood.”

Driving requires a different kind of fortitude. At first, the weather was as good as the gas was cheap, but eventually our southerly route backfired: we saw more snow in New Mexico and Arizona than at higher latitudes. One of our hosts, a kindly German who spent time in Tibet as a young man before becoming an old one in the hills above Santa Fe, strongly encouraged us to invest in snow chains ahead of a coming storm. The advice was sound, but Sheena and I had trouble accepting that problematic amounts of snow could find their way to any part of Arizona. The next morning, in Flagstaff, we could just make out the Jetta under a foot of fresh, white powder, as more flakes fluttered down.

The storm turned into a regional crisis—a frozen-watergate, if you will. “It’s a busy day!” the Arizona Department of Transportation tweeted cheerily when the snow first began to fall. A day later, when it had become easier to ski downtown than drive, that enthusiasm waned: “We’re getting reports of people playing in the snow on the shoulder of I-17,” a spokesperson all but sighed. “Please do not make this unsafe decision.”

A number of unsafe decisions eventually forced the Arizona Department of Transportation to close a ninety-mile stretch of Interstate 40 for nearly two days, effectively stranding us in Flagstaff. We used the time to work through our suddenly provident stockpile of books. In a cozy bed and breakfast, we knocked out about two books each over the next few days—Wolf in White Van, How Should a Person Be?, and others—venturing out occasionally for hot chocolate or pizza. The weather spoiled our plan to see the Grand Canyon, but watching the snow fall from a warm place, the woman I love at my side, was an equally natural wonder.

Ted Trautman has written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Slate, Wired, and others. He lives in San Jose.

Vegetable-snake Undersea Beings: A Belated Correction

Ginsberg in May 1965. Photo: Engramma.it

When The Paris Review interviewed Allen Ginsberg for our Spring 1966 issue, he expressed a sense of conflict about hallucinogens. He treasured their effects on consciousness—“you get some states of consciousness that subjectively seem to be cosmic-ecstatic, or cosmic-demonic”—but his body was having trouble tolerating them. “I can’t stand them anymore,” he said, “because something happened to me with them … After about thirty times, thirty-five times, I began getting monster vibrations again. So I couldn’t go any further. I may later on again, if I feel more reassurance.”

Thomas Clark conducted that interview in June 1965; the issue was on newsstands the following spring. A year later, though, in June 1966, Ginsberg sent The Paris Review the following letter, which recently resurfaced in our archives:

June 2, 1966

To readers of Paris Review:

Re LSD, Psylocibin, etc., Paris Review #37 p. 46: “So I couldn’t go any further. I may later on occasion, if I feel more reassurance.”

Between occasion of interview with Thomas Clark June ’65 and publication May ’66 more reassurance came. I tried small doses of LSD twice in secluded tree and ocean cliff haven at Big Sur. No monster vibration, no snake universe hallucinations. Many tiny jeweled violet flowers along the path of a living brook that looked like Blake’s illustration for a canal in grassy Eden: huge Pacific watery shore, Orlovsky dancing naked like Shiva long-haired before giant green waves, titanic cliffs that Wordsworth mentioned in his own Sublime, great yellow sun veiled with mist hanging over the planet’s oceanic horizon. No harm. President Johnson that day went into the Valley of Shadow operating room because of his gall bladder & Berkley’s Vietnam Day Committee was preparing anxious manifestoes for our march toward Oakland police and Hell’s Angels. Realizing that more vile words from me would send out physical vibrations into the atmosphere that might curse poor Johnson’s flesh and further unbalance his soul, I knelt on the sand surrounded by masses of green bulb-headed Kelp vegetable-snake undersea beings washed up by last night’s tempest, and prayed for the President’s tranquil health. Since there has been so much legislative mis-comprehension of the LSD boon I regret that my unedited ambivalence in Thomas Clark’s tape transcript interview was publishing wanting this footnote.

Your obedient servant

[signed]

Allen Ginsberg, aetat 40

The Paris Review regrets the error. May the record hereafter reflect Allen Ginsberg’s unequivocal endorsement of lysergic acid diethylamide.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

Something Nasty

Johnny Depp in a poster for Mortdecai.

Lately, posters for the film Mortdecai have been popping up everywhere. They feature Johnny Depp and a battalion of costars extravagantly mustachioed and looking wacky. Oh, great, I thought. More of Johnny Depp pretending to be a character actor. That’s what the world needed. Maybe in six months if I’ve seen everything else on a plane and the movies are free.

The posters were designed to intrigue, but I can’t imagine they piqued much curiosity. But of course someone, eventually, had to ask, What the Hell Is Mortdecai?, and in a weak moment, I clicked on the link. And of course, then it all made sense—kind of. The new movie is an adaptation of the Mortdecai series by Kyril Bonfiglioli. The spelling is the same, of course, but it was still hard to believe—these lighthearted posters just bear so little resemblance to the tone of the books, and the preview roams even further.

It’s true, the books are technically wacky. Here’s how Leo Carey described them in The New Yorker when the series was reissued in 2004:

Mortdecai, the son of a peer, never tires of describing the splendors of his cellar, his table, and his tailoring. There is scarcely a meal (or a drink) that is not recounted in detail and meticulously evaluated, and he cannot leave the house without telling you, “I put on a dashing little tropical-weight worsted, a curly-brimmed coker and a pair of buckskins created by Lobb in a moment of genius.” He loves to boast about the fine establishments he frequents in his London neighborhood. “I went a-slumming through the art-dealing district, carefully keeping my face straight as I looked in the shop windows—sorry, gallery windows—at the tatty Shayers and reach-me-down Koekkoeks.” (It is a typical Bonfiglioli touch that the artists mentioned—precisely the kind of respectable nineteenth-century landscapists on which a high-end Mayfair dealer thrives—are just obscure enough to impress the reader.)

You should read the whole piece to get a good sense of the series and its author. The books are kind of like Jeeves and Wooster stories—the author plays this up with Wodehouse references—if Wooster were a psychotic, misogynistic art dealer with a weight problem. Or maybe he’s more a sociopath or just a pathological narcissist. I’m not a shrink. But he’s definitely amoral, and he certainly hates women. The books came out in the seventies and have a particular sort of flinty, urbane nastiness to them: people who love them really love them. Both Frye and Laurie are on record in their admiration for the series, and if you check out any series of online reviews, you’ll see that readers are pretty much evenly divided between those who relish the books’ unflinching, un-PC meanness, and those who are appalled.

I’ll confess to falling into the latter camp. Let it be said, I understand the appeal. The series is raffish, dark, melancholy, unabashedly nostalgic, clever, brash. It takes cozy English mystery tropes and takes a sick pleasure in upending them. “For those who like that sort of thing,” said Miss Brodie in her best Edinburgh voice, “that is the sort of thing they like.”

It is, in fact, the sort of thing I thought I’d like. And a big part of the problem is surely that I started the series out of sequence. I read Something Nasty in the Woodshed first—partly because that was the one I first ran across, partly on the strength of the New Yorker piece, partly because people kept trumpeting the series as a “cult” phenomenon, and partly because the title references the slyly daffy Cold Comfort Farm.

Of course, that’s Bonfiglioli all over: summoning a comforting classic (itself a send-up of hackneyed British literary tropes) and giving it a quick sheep-dip in acid. I like to think I’m able to put aside missish twenty-first-century sensibilities and read something on its merits. But I am a product of my time and a woman. And I found the book—with its caustic, rape-centric plot—ugly. The protagonist may be an unabashed narcissist and the narrator may be winking at the reader, but he certainly wasn’t winking at me. I went on to read the others—Don’t Point That Thing at Me and After You with the Pistol—but the damage had been done. I have never been eager to join clubs that don’t want me as a member.

I imagine the film wouldn’t bother me at all—at least not in the same way. The movie, one imagines, will take away everything that people love in the books and leave only what the author was lampooning. Certainly they seem to have put Mortdecai on a diet, so one imagines he’ll restrain his other appetites with equal zeal. Or maybe I’m wrong: maybe Johnny Depp will play an untrammeled, unlovable sociopath who tramples on modern mores and has contempt for viewers. Yes, I’m sure that’s what will happen. In the tradition of Breaking Bad and The Sopranos, we will see a complex antihero and be drawn to his self-loathing complexity. Done right, an adaptation could indeed be interesting.

Even more interesting—or at least, of our time—would be a portrait of the multifaceted author, who painted himself as “an accomplished fencer, a fair shot with most weapons,” “abstemious in all things except drink, food, tobacco and talking,” who battled depression and alcoholism. He died, financially insecure, before completing The Great Mortdecai Moustache Mystery (which title seems to have inspired the team behind the movie) and it was completed by the great literary mimic Craig Brown, under the aegis of Bonfiglioli’s widow. As Carey wrote, “The undertow of pain and despair is what gives the books an emotional charge beyond their surface urbanity, and makes them stick in the mind long after you’ve quoted all the funny bits to your friends.” On the reissue’s cover, they printed only the end of that quote.

He Was Always Right, and Other News

James Rosenquist, Floating to the Top, 1964. Courtesy VAGA New York and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Merriam-Webster has undertaken a daunting project: they’re publishing a new edition of their unabridged dictionary, which hasn’t seen a major overhaul since 1961. Their employees are already hard at work: “Emily Brewster has produced anywhere from five to twenty-five definitions a week. Twerking is ready, she tells me in December. Nutjob (which dates to 1959) and minorly are good to go. Jeggings is, too. The new sense of trolling looks promising, she says, ‘but first I have to finish hot mess.’ Brewster is very excited about hot mess. Thanks to Google Books, she found it in a machinists union trade journal from 1899: ‘If the newspaper says the sky is painted with green chalk that is what goes. Verily, I say unto you, the public is a hot mess.’ ”

In 1969, the curator Henry Geldzahler convinced the Met to host “New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970,” a show so vast and intensely contemporary that it remains a watershed—so why not just do the whole thing again? “Henry had a fantastic eye. He wasn’t wrong about anything. He was always right.”

A mother from an affluent Texas town would strongly prefer her children to read Ayn Rand in school, not The Working Poor, David K. Shipler’s book about poverty. In other news, Oxfam announced yesterday that 1 percent of the global population holds half the world’s wealth.

George Steinmetz traveled by helicopter to take these aerial photographs of New York in winter. He and his pilot “frequently flew so low that they passed in between buildings, with Steinmetz and his camera hanging out of the open door.”

Remembering Alice K. Turner, who was Playboy’s fiction editor for two decades. “Fiction is kind of a nuisance,” she once said. “The ad sales guys don’t see the point. They would cut it out if they could, except for the fact that it adds a certain respectability … Playboy stories have beginnings, middles, and ends. They have a kind of general appeal. They are not experimental. They are not terribly modern or forward-reaching but they have real quality, or so I hope.”

January 19, 2015

Damn the Absolute

William James, left, and Josiah Royce in New Hampshire, September 1903. When James heard the click of the shutter, he shouted, “Royce, you're being photographed! Look out! I say, Damn the Absolute!”

A letter from William James to his publisher Henry Holt, sent from Cambridge, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1896.

MY DEAR HOLT,—At the risk of displeasing you, I think I won’t have my photograph taken, even at no cost to myself. I abhor this hawking about of everybody’s phiz which is growing on every hand, and don’t see why having written a book should expose one to it. I am sorry that you should have succumbed to the supposed trade necessity. In any case, I will stand on my rights as a free man. You may kill me, but you shan’t publish my photograph. Put a blank “thumbnail” in its place. Very very sorry to displease a man whom I love so much. Always lovingly yours,

WM. JAMES.

A Dissatisfaction with Life

Patricia Highsmith on After Dark, 1988. Photo: Open Media Ltd.

You don’t agree with George Bernard Shaw’s idea that the artist is very close to the criminal?

I can think of only one slight closeness, and that is that an imaginative writer is very free-wheeling; he has to forget about his own personal morals, especially if he is writing about criminals. He has to feel anything is possible. But I don’t for this reason understand why an artist should have any criminal tendencies. The artist may simply have an ability to understand … I would much rather be an entertainer than a moralizer, but to call murder not a social problem I think is ridiculous; it certainly is a social problem. The word existentialist has become fuzzy. It’s existentialist if you cut a finger with a kitchen knife—because it has happened. Existentialism is self-indulgent, and they try to gloss over this by calling it a philosophy … I once wrote in a book of mine about suspense writing, that a criminal, at least for a short period of time is free, free to do anything he wishes. Unfortunately it sounded as if I admired that, which I don’t. If somebody kills somebody, they are breaking the law, or else they are in a fit of temper. While I can’t recommend it, it is an awful truth to say that for a moment they are free, yes. And I wrote that in a moment of impatience, I remember distinctly. I get impatient with a certain hidebound morality. Some of the things one hears in church, and certain so-called laws that nobody practices. Nobody can practice them and it is even sick to try … Murder, to me, is a mysterious thing. I feel I do not understand it really. I try to imagine it, of course, but I think it is the worst crime. That is why I write so much about it; I am interested in guilt. I think there is nothing worse than murder, and that there is something mysterious about it, but that isn’t to say that it is desirable for any reason. To me, in fact, it is the opposite of freedom, if one has any conscience at all.

That’s Patricia Highsmith in an illuminating 1981 interview with Armchair Detective, which found her in an unusually philosophical mode, especially vis-à-vis the criminal psyche. Highsmith, who was born on this day in 1921, is best known as the author of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley. Her novels are, as her biographer Joan Schenkar writes, “brilliantly disorienting narratives of such shimmering negativity ... that they are like nothing else in their literary landscape ... [they] suck another reader into their bottomless vortex of moral relativities, transferable guilts, and unstable identities.”

Highsmith had a famously torturous personal life: she lived in isolation, drank to excess, and strained to cope with her feelings for other women. She never married, and none of her affairs lasted long. She had a habit, Schenkar notes, of “repeatedly seducing her lover’s lovers—and those lovers’ lovers as well.

The playwright Phyllis Nagy put it simply: “She had a dissatisfaction with life.”

Highsmith’s fascination with criminality connects to a whole subterranean network of misanthropy: in her notebooks, she described life in the mid-twentieth century as “a catalog of various subterfuges and camouflages, sedatives and intoxicants … [a] sense of chaos and decadence [pervades] my age. The greatest achievements in my age in writing will be made by students of chaos. Lines fly off in every direction, and where they cross is no point of sanity or security.” But those notebooks were also her only venue for a kind of longing:

Persistently, I have the vision of a house in the country with the blond wife whom I love, with the children whom I adore, on the land and with the trees I adore. I know this will never be, yet will be partially that tantalizing measure (of a man) leads me on. My God and my beloved, it can never be! And yet I love, in flesh and bone and clothes in love, as all mankind.

Online, interviews and recordings of Highsmith are sadly hard to come by—I could only dredge up this 1987 radio piece, strictly for devotees. Her interlocutor speaks as if he’s spent decades imprisoned in his studio with a low-grade fever. “I don’t think I’ve been to a party for two years,” he says at one point, marveling at the active social lives of her characters. And, elsewhere: “I’m told they don’t publish hardcover books in France … Isn’t that shocking?”

Highsmith, for her part, does not seem shocked.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers