The Paris Review's Blog, page 621

January 30, 2015

I Swear

In 1904, Roland D. Sawyer launched a crusade against obscenity.

No one ever heard my grandmother, in all her eighty-three years, utter a bad word. I can only once remember her even raising her voice. “It’s all fouled up!” she cried then, shaking a broken TV set. She said it with such frustration and despair that it expressed at least as much as any curse word might have. In fact, besides the time I heard a four-year-old in my brother’s playgroup call his sister Mary-Ellen a “fuckindamnshit,” it was the most shocking thing I’d ever heard.

Her husband, my grandfather, was considered foul-mouthed in the family; his language was a constant cause of distress to her. But in fact, he didn’t use real swear words either—certainly not compared to that little boy. It was usually a savage Goddammit! Or Hell’s Bell’s! His worst outbursts were reserved for his weekly gin game. It was then that he’d reach for the worst epithet of all: “I’ll be dipped.”

“I’ll be dipped”—said with a vehement emphasis on the last word that hinted at incipient violence, and with an Arkansas accent—was all the scarier because we weren’t sure what it meant. Sheep dip? Boiling oil? As a grown-up, I’ve heard it since in the South (or in its cruder form, “I’ll be dipped in shit!”) but it’s always a benign expression of surprise. Never does it convey the menace that my grandfather’s version did.

It’s true that curse words tend to be ugly—guttural, coarse, basic—but then, any word can be made ugly. There just needs to be enough rage behind it, the way something innocent can be turned into a weapon.

The funny thing is, it works the other way, too. I'm thinking of another incident involving my grandmother, this one at the kitchen table after dinner one night. We were playing Boggle, as we often did; my grandmother excelled at word games. The little egg timer had run out of sand and it was my grandmother’s turn to read aloud the list of words she had found in the jumble of letters. As usual, she had a lot: SQUARE, JAMS, TRUCE. And then she paused. “I wasn’t quite sure about this one. C-U-N-T. That’s a word, isn’t it?” She looked around the table inquiringly, while several of her adult children dissolved into helpless laughter. “Does it mean something funny?” she asked, looking bewildered. At length, one of my uncles explained. She went white, and stood up and walked out of the room.

It was the first time I’d heard that word, too. Maybe that’s why I’ve never found it as awful as I really should.

Sadie Stein is a contributing editor of The Paris Review, and the Daily’s correspondent.

All in One: An Interview with Tomi Ungerer

Tomi Ungerer. © Luc Bérujeau

At the opening for the Drawing Center’s “All in One,” Tomi Ungerer’s first U.S. retrospective, swarms of visitors obscured the art on the walls. The crowd bent toward the artist, who was holding court and a glass of red wine, though none was being served. Ungerer, who is eighty-three, was in his element. For him, this retrospective is a kind of homecoming. After more than forty years in exile, his career is finding its rightful place in the New York art world.

The Drawing Center exhibition, curated by Claire Gilman, begins with Ungerer’s earliest doodles as a child growing up in Nazi-occupied Alsace, where under the nationalistic duress of war he first learned to be an outlaw. Delicately subversive, they are inscribed with a mature, swaggering humor that takes a subject as terrifying as Hitler and renders him a fool.

In 1956, Ungerer was lured to New York City at the height of print, when publications offered vast opportunities for creative illustrators. Without contacts or even a high school diploma, Ungerer impressed art directors with his idiosyncratic drawing style and witty candor. He became sought after for advertising and editorial work, and most prominently, his unconventional children’s books, which featured society’s most repulsive characters—robbers, snakes, pigs, beggars—as compassionate protagonists.

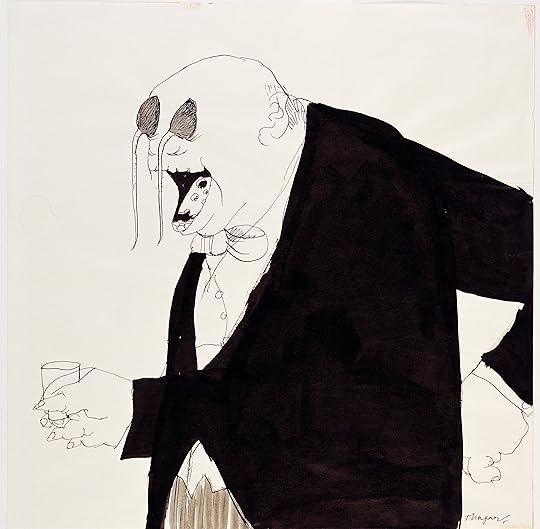

Untitled, 1966 (drawing for The Party, first published by Paragraphic Books, Grossman Publishers, New York), ink and ink wash on paper, 18" x 18". Collection Musée Tomi Ungerer/Centre international de l’Illustration, Strasbourg. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich. Photo courtesy Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Mathieu Bertola.

While working professionally in these PG-rated circles, he remained a deeply political artist, self-publishing bold posters against the Vietnam War, a book of harsh satire called The Underground Sketchbook, and sadomasochistic erotic drawings. But upon discovering his erotic work, the children’s-book community was scandalized. His books were removed from public libraries and his reputation tarnished. Dejected and unable to find work, he left New York in 1971, moving to Nova Scotia with his wife before finding a permanent home in Cork, Ireland.

This defection cost Ungerer the renown he deserves. It wasn’t until 1998 that he received the Hans Christian Andersen Award, the highest achievement for children’s-book authors, and a sign of the recent reappraisal of his career. Recent years have seen reissues of his children’s books in English and a large catalogue of his erotic drawings. In Strasbourg, he has a museum dedicated to his work, and in 2012, his life was the subject of a documentary film.

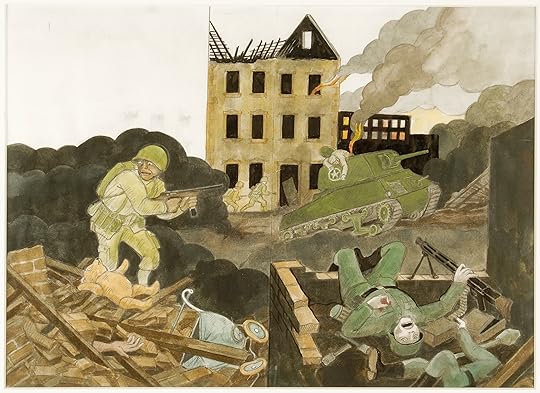

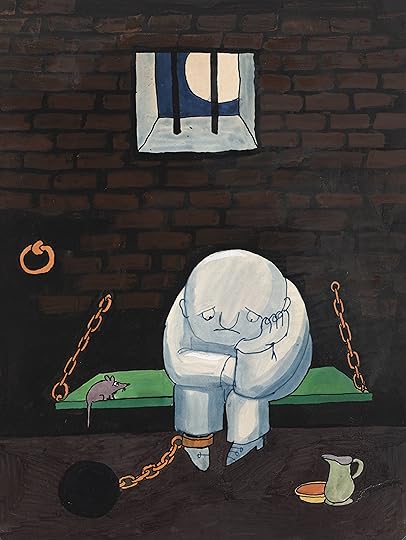

Untitled, 1999 (drawing for Otto: The Autobiography of a Teddy Bear, first published by Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich), pencil and ink wash on paper, 12" x 16". Collection: Musée Tomi Ungerer/Centre international de l’Illustration, Strasbourg. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich. Photo courtesy Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Mathieu Bertola.

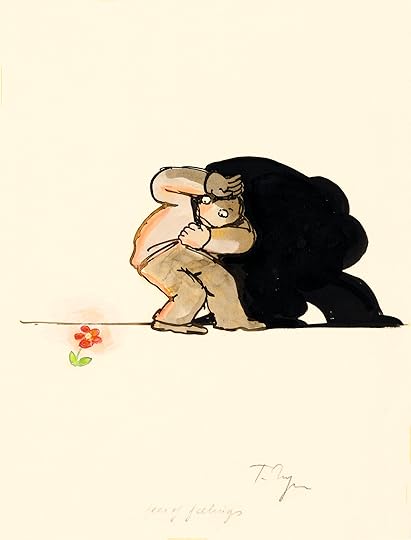

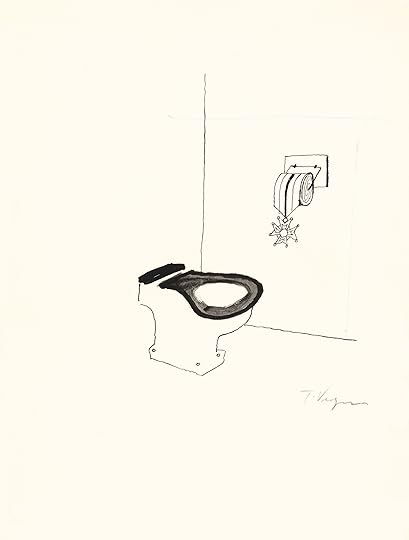

Fear of Feelings, 1982 (drawing for Symptomatics, published by Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich), ink, ink wash, and colored pencil on tracing paper, 10" x 8". Tomi Ungerer Collection, Ireland. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich

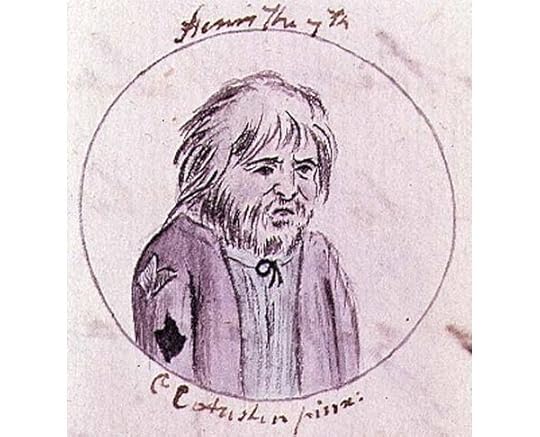

Untitled, 1944, pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper, 8 1/4" x 9". Collection: Musée Tomi Ungerer/Centre international de l’Illustration, Strasbourg. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich. Photo courtesy Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Mathieu Bertola.

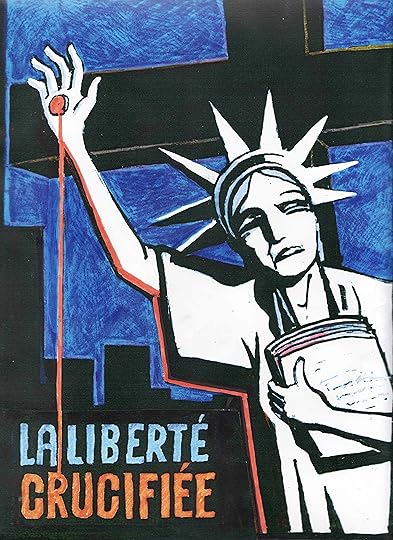

“All in One” follows this trend, showing that Ungerer has been anything but inactive since leaving New York. The range of subject matter is astounding, spanning the terrors of World War II and the turbulence of the sixties, and reaching into the present, with a last-minute addition of the artist’s response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks: a cartoon of Lady Liberty crucified.

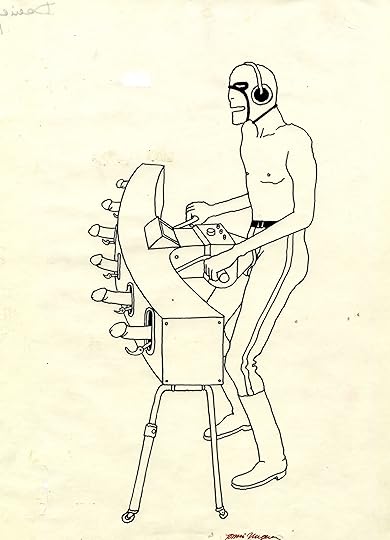

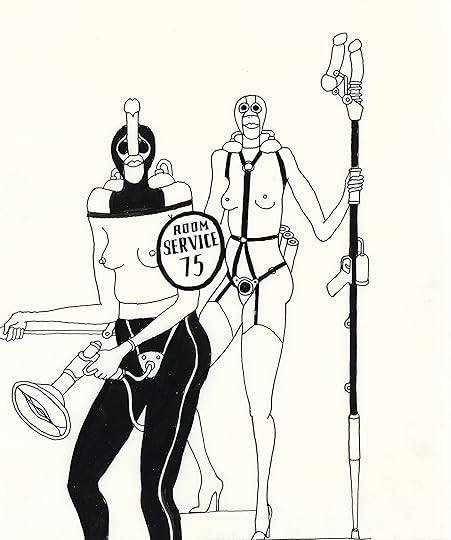

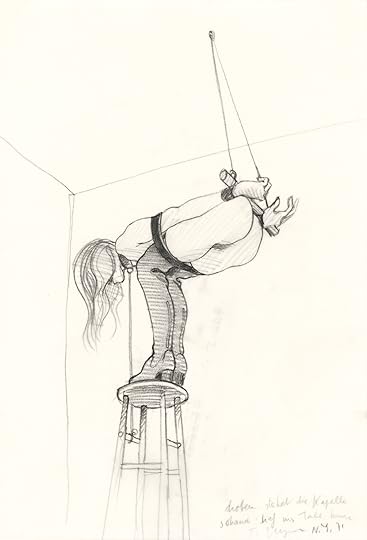

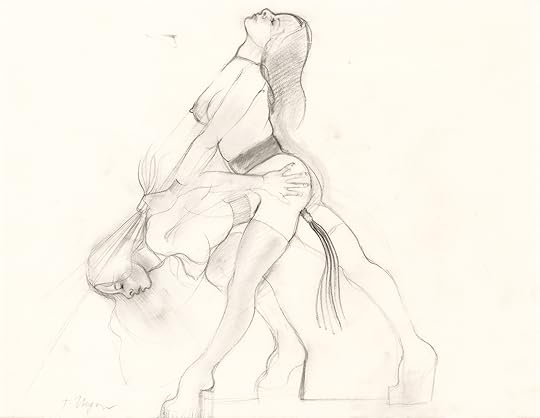

His career represents a bygone era of eccentricity in advertising and the revolutionary potential of children’s books. Observed without the sheen of controversy, his erotic work is full of nuance: Fornicon has a fluorescent-lit quality, and steady black lines imagine men and women equipped with bizarre sex machines, like rickety, salivating superheroes. In contrast, Totempole, also using sadomasichism’s external devices and scenarios, expresses inwardness through the sketchy, hesitant line of specificity. These erotic works are given their own separate gallery, with a disclaimer for parents of young children. It’s hard to avoid, as the gallery’s entrance sits just above a theater screening animated film adaptations of Ungerer’s children’s books. On opening night, giggles erupted up the theater steps; the crowd was mostly adults.

I met Ungerer a few days later at his hotel in Soho, a neighborhood that epitomizes the city’s transformation since the time he ran wild here. His features have been sharpened rather than softened by time, and his blue eyes project lively light. In an art world that has grown to valorize polite professionalism, Ungerer’s irreverent personality has the air of a once-upon-a-time legend. He’s quick to inject dark humor into the most mundane interactions. He begged the waiter for decaffeinated coffee, declaring, “Otherwise I will blow up. But don’t worry, you are invited to my funeral. Look, you’re already all dressed in black for the occasion!” He soon hijacked the interview, beginning with his own line of questioning.

Untitled, 1967 (drawing for Moon Man, page 19, first published in 1966 as Der Mondmann by Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich), pen and ink and tempera on paper, 12 5/8" x 9 3/8". Children’s Literature Research Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia

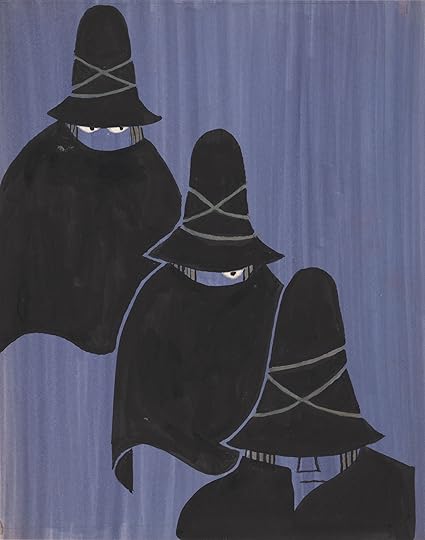

Untitled, 1961 (drawing for The Three Robbers, page 5, first published as Die drei Räuber by Georg Lentz Verlag, Munich), colored pencil, gouache, and watercolor on paper, 11 7/8" x 8 5/8". Children’s Literature Research Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia

Have you read my piece in the [All in One] catalogue?

I did. I was especially intrigued by your aphorisms, which you end your essay with. Could you tell me a bit about those?

People call me an illustrator, but I have been only occasionally an illustrator. In France or Germany I’m known as a writer and as a drawer. These aphorisms are my specialty. They’re all published in France and Germany and are untranslatable usually, because they’re a play on words. I would call them sayings, because aphorism is pretentious—it means there’s a certain wisdom. And one of my aphorisms is, “How boring is wisdom?”

I think of some of your greatest works as visual aphorisms.

For me, it has to be concise. This is why I reject all cartoons which have something written, where there’s a man, and then it says, Income tax. No! The drawing has to be able to speak without any balloon or anything. It just has to jump out and be clear. And I learned that from Steinberg. Steinberg is not so much an influence for the line. Steinberg was, for me, an intellectual experience—that with a few lines he could put a whole thought.

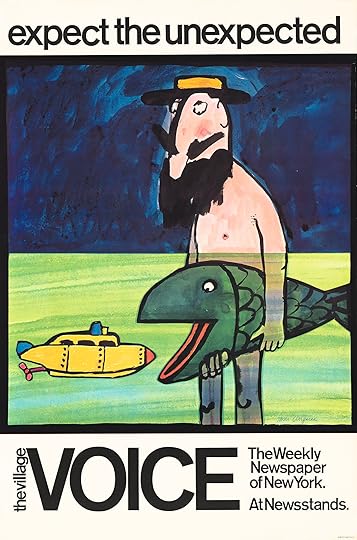

Untitled, 1968 (poster for the Village Voice), 44 1/2" x 29 1/2". From the collection of Jack Rennert, New York. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich. Photo courtesy Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Mathieu Bertola.

But to me, Steinberg was an observer. I think of you as more of a provocateur. What role do politics have in your work?

In a way, my whole life has been working and fighting for causes. Goebbels was another enormous influence, because I grew up under Nazi propaganda. Goebbels showed me that if you want to demolish your enemy, you use his own weapons. Which is what I’ve done. I’ve been fighting fascism and violence, but with the same technique, which is just power. I mean, a poster has to hit you. And this is very interesting because in German the word slogan is translated as a “fist-word,” Schlagwort. Schlag means hitting. So it’s a word that hits. It’s the same with visuals, because even if a poster goes by on a bus, it has to stay in your mind.

So do you see your work as always on the offensive?

I don’t calculate. I’m just spontaneous. I do crazy things without thinking. Sometimes I do something with a purpose. I did a children’s book, Making Friends, which is about a black boy coming to a white neighborhood—that was done with a purpose. A lot of my energy went to big campaigns, like for AIDS and cancer. For AIDS, it was so much fun—we gave away something like 500,000 condoms free in the street, and on every condom was a drawing of mine, a silhouette of a naked girl with a butterfly net catching a heart, but the butterfly net was a condom. Can you imagine 500,000 of those being handed out in the streets? This would be unthinkable in America! I must say, I’ve always had my fun, too, you see.

Your fun came up against those American puritanical values. What’s it like to see your erotic works displayed in the Drawing Center exhibition when they were so controversial in the past?

I was ahead of my time. Taschen came out with a huge book of my erotic works and I was delighted to see that, when it came out, there were sometimes more women than men at a signing, which would have been unthinkable in the time.

Untitled, 1969 (drawing for Fornicon, first pubished by Rhinoceros, New York), ink on tracing paper, 14" x 11". Collection: Musée Tomi Ungerer/Centre international de l’Illustration, Strasbourg. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich. Photo courtesy Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg.

Untitled, n.d. (drawing for Fornicon, first published in 1969 by Rhinoceros, New York), ink on tracing paper, 14" x 11". Tomi Ungerer Collection, Ireland. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich

Droben Stehet die Kapelle schauet tief ins Tal hinein (Rise above, behold the chapel deep in the valley), 1971 (variation on Totempole, published 1976 by Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich), grease crayon and pencil on tracing paper, 16 9/16" x 11 13/16". Tomi Ungerer Collection, Ireland

Untitled (In Bewegung) (In motion), c. 1974 (variation on Totempole, published in 1976 by Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich), pencil on tracing paper, 11 1/16" x 14". Tomi Ungerer Collection, Ireland

When you came to New York, it was the heyday of print and your work was widely distributed. Do you think those kinds of opportunities have changed for illustrators in the digital age?

Those days are over. These days, all the advertising money goes into television. And in the olden days, all the money went into the magazines. Even magazines like Colliers or Look published stories, so the illustrators were on hire. The first cartoon I sold to Esquire was full page. I would sell some of my children’s books as a story for the Christmas issue of a magazine. Moon Man came out originally in Holiday magazine—twelve pages for Christmas. It was incredible.

You mentioned your dislike of captions, but you’ve always been a storyteller. How and why do you use language in your children’s books?

Well, this was a big fight in the old days. Still, to this day, the Americans say that you should use a vocabulary that the children already have and understand. And I say, No. Children should be given a challenge with new words. My wife and I read our children stories every night—but way ahead of their age. Why not read The Little House on the Prairie to a four-year-old child? I never had this problem with Ursula Nordstrom at Harper. She was the only one who didn’t give a shit about this. But when The Three Robbers came out, they wanted me to take out the word blunderbuss for the gun. But blunderbuss—isn’t that a beautiful word? My god! Blunderbuss!

So a children’s book should be a challenge?

Exactly. It makes them curious for more words. And I always talk to children and youngsters as if I was talking to an adult. This is what people do in Ireland and in Europe. You don’t do goo-goo, gaga. C’mon! They’re young adults, they understand fast. I had to learn German when the Germans arrived in Strasbourg. After three months, one merci and you’d be arrested. Put the knife at their throat and they’ll learn fast enough! These days, I’m personally responsible for the teaching of the Holocaust in French schools. My book Otto is used, and my memoirs of my childhood under the Nazis.

Obviously France has been the center of the discussion on the power of cartoons today. What’s it like to see the world coming to the defense of cartoonists and their work?

Of course I was devastated. The drawing I did on Charlie Hebdo is in the show. It’s a sad drawing. I don’t feel appalled, because it’s written on the wall. It’s the beginning of the World War III. World War I was in the trenches, World War II was in the air, and now we have the Internet and underground terrorism. And there is no way you can uproot that. What happened in Paris was absolutely to be expected, sooner or later.

Liberté Crucifiée, January 9, 2015, ink wash and colored pencil on paper, 12 1/8" x 9". Tomi Ungerer Collection, Ireland, © Tomi Ungerer

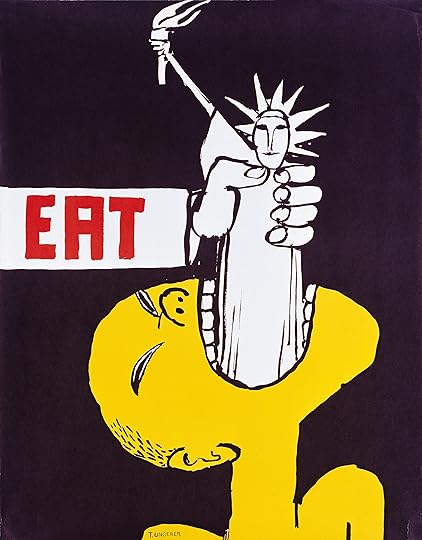

Eat, 1967 (self-published poster), 26 1/2" x 21". From the collection of Jack Rennert, New York © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich. Photo courtesy Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Mathieu Bertola.

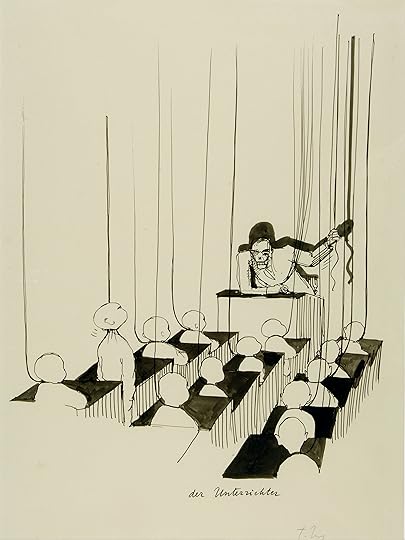

Der Unterrichter (The Teacher), c. 1980 (drawing for Rigor Mortis, published in 1983 by Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich), ink and ink wash on paper, 19 3/4" x 15 3/4". Collection: Musée Tomi Ungerer/Centre international de l’Illustration, Strasbourg. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich. Photo courtesy Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Mathieu Bertola.

There’s been a lot of discussion on the racism in the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. In your earliest childhood drawings, I see you grappling with the stereotypical imagery of Nazi propaganda—and later, in your drawings for the Underground Sketchbook and The Party, you satirize businessmen in their suits. What role do you think types have in your work, and when do they become stereotypes?

Society is made of types, and I’m an accuser, pointing my finger. An accuser, not a judge, please, because I would have to judge myself before I judge others. But I’m just pointing out all the negative aspects of society. I’m reckless, but when I personally have done satire, I have always shown respect for what people respect.

Untitled, c. 1964 (variation on The Underground Sketchbook, first published in 1964 by Viking, New York), ink, ink wash, and colored pencil on paper, 11 1/16" x 8 5/8". Tomi Ungerer Collection, Ireland

Your attitude has been clear, but your style has changed drastically over time. What’s it like to see the work of your entire career together in the Drawing Center show?

Well, you have to understand that I’m a bit of a spoiled brat. The last show I had in Germany was in a museum where I had four thousand square meters. I could have a room for every style. But I usually hate shows because the transitions between styles and periods are abrupt. I’ve always been embarrassed. I’m like a butterfly, just going from one thing to another. It’s not part of a plan or something. It’s my freedom. I cannot take myself seriously. So to come to the Drawing Center—this is a rather small show, and this is what makes it extraordinary. Claire was able to get from one style to another, and you don’t feel the change. It’s like, flowing. There’s hardly anybody who’s been able to do that. Claire really put order in my life.

Do you think of yourself primarily as a realist or as a fantasist?

Both. I believe reality illustrates itself by the absurd. But in terms of my philosophy, one of my famous sayings is, “Don’t hope, cope.” I’m totally realistic. I don’t believe in illusions. In the papers, I read between the lines. What really strikes me is the total absurdity of our world. Even this killing is totally absurd. When you have the absurd, you have fantasy, and when you see the absurd in facts, then you have the facts. That’s the key.

Sarah Cowan is a freelance writer and a video editor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She lives in Brooklyn.

Jane Austen: Teen Historian, and Other News

An illustration of Henry VII by Cassandra Austen, Jane’s sister.

In 1791, a fifteen-year-old Jane Austen wrote The History of England, a satirical pamphlet “by a partial, prejudiced & ignorant Historian,” featuring watercolor illustrations by her sister, Cassandra.

Out of print and in demand: What are the most sought-after books no longer being published? Norman F. Dixon’s On the Psychology of Military Incompetence (1976) leads the list—there’s also “an enthusiast’s guide to building bamboo fly-rods” and Madonna’s Sex.

Tom Stoppard’s new play is opening at the National Theatre in London. Tickets are very hard to come by—it might be easier just to write your own Tom Stoppard play. Here’s a step-by-step guide. Remember, “what you’re aiming for is intellectual sparring that manages to be tragic and comic at the same time, while alluding to a universal emotional truth and revealing a vast, in-depth knowledge of the literary canon. Basically like the way you think you talk to your oldest friend when you’re both drunk. Do not shy away from paradox and metatextuality!”

Or maybe you’d rather try your hand at some fiction from Africa. In 2006’s How to Write About Africa, the Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina advised, “Always use the word Africa or Darkness or Safari in your title … be sure to leave the strong impression that without your intervention ... Africa is doomed.” But in the years since he made those pronouncements, “writing from Africa has flowered, and many of those clichés have been dispelled … This is a fertile moment when young writers are emerging as some of the elders they grew up reading are still at their peak … This cross-generational richness enhances a literature that today ranges from dirty realism and crime thrillers to science fiction, digital serials and graphic novels.”

One man’s intrepid journey into the craft of hand-making lace: “I had no teacher, and unlike knitting classes in knitting stores, never considered that I could find one even in a metropolis like New York City. Indeed, if you ask employees in yarn stores if they have any tatting supplies, half will not know what you are talking about and say no, and the other half will know what you are talking about but still say no.”

January 29, 2015

Common Colds

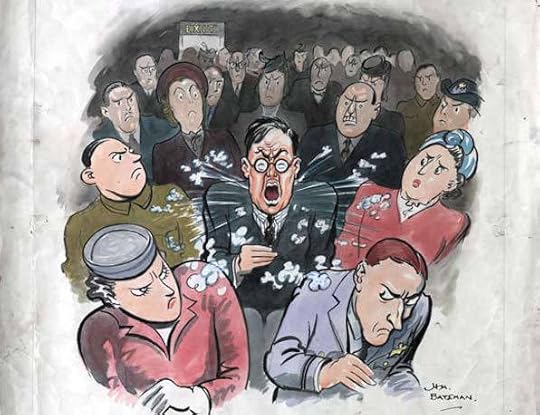

“Coughs and sneezes spread diseases,” a famous British public health campaign.

As I wandered through the painkillers aisle, sniffling and throwing decongestants and tinctures into my basket, I thought that one of the annoying things about the common cold is the knowledge that it’s so benign. A harried-looking dad was bending over the babies’ section, staring at a bulb syringe and trying ineffectually to calm the miserable toddler in the red UPPA. The little boy was howling. And why not? What had he done to find himself visited by a raw, red nose, troubled sleep, and a series of aches and pains? So far as he was concerned, this was the end of the world: nothing in this moment could have been worse.

And the truth is, when you feel sick, it’s a small comfort to know you’ll be better within a week and what’s happening to you isn’t, in fact, serious. There’s none of the anxiety of a real medical problem, but then it’s in a different category entirely: it’s the very knowledge of its toothlessness—paired with its unpleasantness—that renders it irritating.

What else in the world is like this? I tried on various feelings and memories as I walked home, and then it came to me: Internet meanness. Being trolled by someone on the Internet is one of the few things that feels like a common cold. It happens, it’s ubiquitous, you know that you can’t give into it—and it’s none the more pleasant for that. Those things which are all about one’s toughness—that really only differ in how you stand up to them—are a particular sort of exhausting.

Like a cold, there’s no “good” trolling—only degrees of badness, and various capacities to cope and palliate. You can strengthen your immunities, as it were, but putting yourself into the world means exposure.

There are, of course, degrees of awfulness—check out Lindy West’s recent turn on This American Life to hear an extreme recent example—and it’s an inexact and stupid comparison. It becomes very tempting to say something really hackneyed: that both are easier to bear when you hold your head up. But I’d be lying; I ignore these sorts of things to the greatest extent possible, brood when I can’t, and turn off comments. It’s been a while since I cried about such things, and for the first time this week, I read an insult from a stranger and didn’t take it to heart. It only took ten years. And someone calling me “a goblin fart,” of course.

I know I’m belaboring it, but I do think there’s something there. The human body’s a remarkable thing, but after millennia, we still get colds. Maybe we always will. And no one should ever grow inured to cruelty and pain; we are not built for it. Babies haven’t learned much perspective, but that doesn’t mean that, strictly speaking, they’re wrong.

Explorations and Surveys

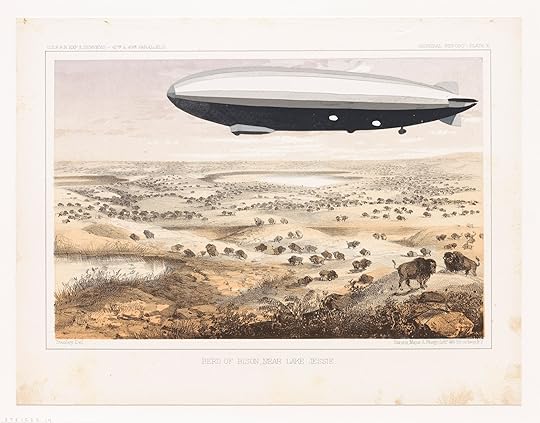

William Steiger, USPRR Herd of Bison, 2014, gouache, glue, vintage lithograph, paper, 9" x 11¼".

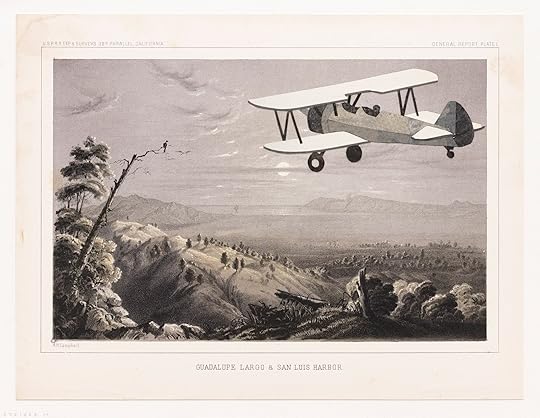

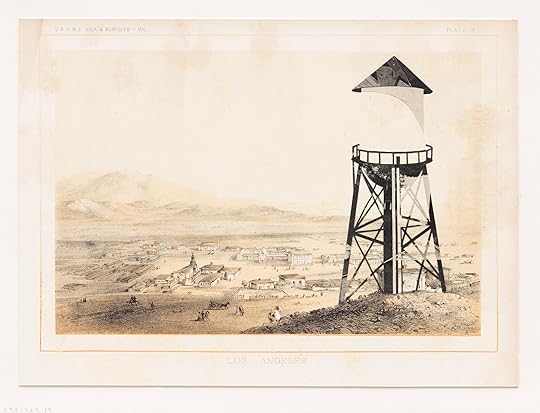

William Steiger’s collages are wondrous, often humorous refractions of early American landscapes. They traffic in a very particular kind of anachronism, grafting zeppelins, prop planes, gondolas, bridges, and the gleaming apparatus of the steam age onto the vast plains and prairies of the nineteenth-century frontier. The images dare us to reconcile two equally innocent visions of American life. One is taut, sleek, and brimming with technological optimism; the other is lush, free, and unspoiled. Neither, it goes without saying, have quite panned out as our forebears hoped they might.

The series, “Explorations & Surveys,” plays with our country’s mythology, conflating more than a century of travel and invention into pale stories of our naïveté—everything in the world of these images is still ours for the taking. Steiger constructed the pieces using a nineteenth-century surveyors’ guide. His gallery, Pace Prints, explains:

Steiger borrowed the abbreviated title, Explorations & Surveys, from the title of his source material, Reports of the Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economic Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. These accounts were published by the Federal Government in the late 1850s to both document the western regions and to locate the best routes for the forthcoming Pacific Railroad. Disseminated in bound editions, the volumes were essentially the first published images of the American West.

These works, and others, are on view at Pace Prints Chelsea through February 21, with an opening reception tonight at six.

USPRR San Luis Harbor, 2014, gouache, glue, vintage lithograph, paper, 8¾" x 11¼".

USPRR Los Angeles, 2014, gouache, glue, vintage lithograph, paper, 8½" x 11¼".

Silvercup, 2014, aquatint and soft ground etching, 21½" x 29".

The Pomegranate Architect

Becoming the world’s only accidental architect.

From the cover of Sam Weller’s Ray Bradbury: The Last Interview and Other Conversations.

I first met Ray Bradbury while writing a feature story for the Chicago Tribune magazine in 2000, the year he turned eighty, and we quickly bonded over our shared childhood experiences (roughly fifty years apart) growing up in northern Illinois, as well as in Southern California. We had a remarkable number of things in common and a similar sense of curiosity and a joie de vivre, and we began to work together closely, as I became his authorized biographer.

For two years, from early 2010 to April 2012, Ray had an essay that he wanted to work on each time we met. It was always one of the first things he mentioned—“Can we work on my architecture essay today?”

Despite the fact that he had written about his work in the field of architecture in his book of essays, Yestermorrow, and I had surveyed his work extensively in my biography, Ray was resolved to get the entirety of his creations in the field of architecture down in one essay. He wanted me to submit it to Architectural Digest. The essay was never completed—it was never quite right, because he always had more memories or thoughts he wanted to add to it. And it was rough, having been dictated over many months. Even on the occasion of his ninetieth birthday, with guests in the house, he called me into his den and asked me to record a new section. And the very last time I saw him, less than two months before he passed, he asked me again to help him finish it. There was something vital about this essay to Ray Bradbury—he wanted, I think, to prove to the world his influence on the field of architecture. Whatever the case, he very much wanted this essay published. It is presented here and in Ray Bradbury: The Last Interview and Other Conversations, in rough form, for the very first time. —Sam Weller

How did I become an architect? It was all a happy accident. I suspect it began when I was three years old, living in Waukegan, Illinois, in 1923. My grandfather influenced me by showing me architecture. He had pictures of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, and of the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. I looked at these pictures through an old stereopticon, a Viewmaster, and I could see all the old, beautiful buildings.

When I was five, my grandfather influenced me yet again. And I think this caused me to go on and to eventually influence other people and to start thinking about public spaces and buildings myself. My grandfather was so important. When I was around five years old, he showed me a copy of the magazine Harper’s Weekly. It was an issue from around 1899, and it contained a story by H. G. Wells called “When the Sleeper Wakes.” The story had marvelous illustrations showing the cities of tomorrow. They were so beautiful. I fell in love with those pictures. They burned into my subconscious.

In the fall of 1953, when I was thirty-three, I had just finished writing Fahrenheit 451. I went off with my wife and two young daughters to France, and England, and eventually to Ireland, to write the screenplay of Moby Dick for John Huston.

When we arrived in London, we walked around town in the fog one night and we went to 221B Baker Street, and there was nothing there. I said, “My God! This is terrible! This is where Sherlock Holmes lived! There should be something here to indicate that this is where he lived.”

So the next day, I wrote to Scotland Yard, and I said, “You have to put a sign where Sherlock Holmes once lived!” And then I wrote to the consort of Queen Elizabeth. I knew he loved Conan Doyle. I said to the consort, “Arrange to have a sign put at 221B Baker Street, indicating that’s where Sherlock Holmes lived.” Today, as I understand it, there is not only a sign—there is an entire museum dedicated to Sherlock Holmes. And the underground Tube stop at Baker Street indicates it as well. So maybe, in a way, I began as an architect then.

A few years later, in the early 1960s, around the time of the publication of my novel Something Wicked This Way Comes, a young man working at the Disney studio saw an article that I wrote about a new edition put out by Bantam Books of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne. I wrote the introduction to that book and in it, I compared the author of Moby-Dick to the author of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Herman Melville and Jules Verne. I called it “The Ardent Blasphemers.” That young man at Disney sent that article to his friends in New York City who were, at that time, helping build the New York World’s Fair, and they read the introduction and they came to Los Angeles a month later and they knocked on the door, and I opened the door and they said, “Mr. Bradbury, shall we tell you why we are here?”

I said, “Why?” “We are here to give you a fifty-million-dollar building.” I said, “What!? Come in, come in!”

So I brought them into the house and I said, “Why are you telling me this?”

They told me that they had just read my introduction about Jules Verne and Herman Melville in the Bantam edition of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. “We think you are the most American of all writers,” they said, “and we want you to work with us and help us build the United States Pavilion at the World’s Fair, which will be opening in two years. They asked me if I could write an eighteen-page script on the history of America with a full symphony orchestra.

I said, “Yes, I can do that.”

By God, they put me to work. I wrote the script and when it was finished they recorded it with a full symphony orchestra, and when they built the United States Pavilion for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, at the center of it all was my program. So I became an architect, not realizing I would become one. The whole top floor of the U.S. Pavilion was the history of America starting five hundred years ago and coming forward through time, through Founding Fathers and the American Revolution and it ended on our possible voyage into outer space. So I helped create this, and it was my first job as a sort of architect.

A few years later, Walt Disney and his people came to me and said, “We are going to build a future city called EPCOT. Will you help us?” I said, “I will do that.” And so they told me about a great building they were planning called Spaceship Earth, and they asked if I would write the metaphors for the program inside. It would be a voyage through the history of the Earth. Not the history of America, as I had done at the 1964 World’s Fair, but the history of all mankind, starting with Adam and Eve and coming up through the Neanderthal man and then into the procreation of the various races of man all over the world. The Disney people said, “If you provide us with the metaphor and the poetry, we will place it at the center of Spaceship Earth.”

So sure enough, back in 1982, EPCOT opened, and Spaceship Earth was at the center of it all. Once again, I had become a designer, an architect, writing the script that would provide the blueprint for the interior of the centerpiece at EPCOT.

When they designed the Orbitron at Disney Paris, they hired me again to consult. I told them that the rockets should fly one against the other, in separate directions, so when they met, they met at greater speeds. And that’s the way they built it. They are planning a Disneyland in China. I believe, rather than the Matterhorn ride at the center of the park, they should build a giant dragon coming down a mountain, and people ride down the tail and along the back and all across this giant mythical beast.

All of this work with the Disney people over the decades began because of that one young man and the love the Disney people had for me.

So then, in the years following my work for the Disney people on the 1964 World’s Fair, I became worried about the way Los Angeles was looking. It was falling apart at the seams. In 1970, I wrote an article for the Los Angeles Times Sunday magazine re-creating the center of L.A. called “The Girls Walk This Way; The Boys Walk That Way.” Sometime later, a renowned architect named Jon Jerde came to me and said, “Have you seen the Glendale Galleria?”

I said, “Yes, I have.” “Did you like it?” he asked. I said, “Yes.” He said, “That’s your Galleria. It’s based on the plans that you put in your article in the essay in the Los Angeles Times.” I was stunned. I said, “Are you telling me the truth? I created the Glendale Galleria?” “Yes, you did,” he said. “Thank you for that article that you wrote about rebuilding L.A. We based our building of the Glendale Galleria completely on what you wrote in that article.”

Sometime later, 20th Century Fox was suffering because their films were not making any money. They had made Cleopatra, and it had bankrupted the studio. So they sold the northeast corner of their back lot to a group that was going to build a mall called Century City. Because of my work on the Glendale Galleria, they came to me, and I looked at their plans and told them that it wouldn’t work. They weren’t putting the right things into the mall. They didn’t listen to me and they built it anyway. A year later, they came back to me and I told them how to rebuild the mall. This time, they listened. I told them how to make it more social—they had to put out two hundred tables and chairs and parasols. There had to be twenty or thirty more restaurants! So at the center of Century City, after they had rebuilt it, there was a nucleus of thirty restaurants where you could buy all kinds of food and carry it out to the tables and chairs and umbrellas I had talked about. I also recommended they put a first-class bookstore—Brentano’s—there, and upstairs above that, ten motion picture theaters, so they did it all. There was a center of book reading, and moviegoing, and dining. I suggested they add a really good hot dog stand, and they did it. I said, “Somewhere you have to have a man who sells popcorn,” and they did that, too. As a result, they reopened the second version of Century City, and it was a great success. People came in by the thousands every day. The City kept building, and today it is in very good shape.

Then, in San Diego, in the 1970s, they were rebuilding downtown. I wrote an essay called “The Aesthetics of Lostness,” once again for Jon Jerde, the architect. The premise behind the essay was building a city where people could spend an afternoon, getting safely lost, just wandering about. Jon Jerde built Horton Plaza in downtown San Diego using my essay as his touchstone.

A few years later, a planning group looking at ways to rebuild Hollywood came to me and asked if I would help rebuild Hollywood. Hollywood at that time was beginning to resemble Hiroshima at high noon. I told them that somewhere in the city, they had to build the set from the 1916 film Intolerance by D. W. Griffith. The set, with its massive, wonderful pillars and beautiful white elephants on top, now stands at the corner of Hollywood and Highland avenues. People from all over the world come to visit, all because I told them to build it. I hope at some time in the future, they will call it the Bradbury Pavilion. But much more needs to be done with Hollywood. There is much work left to do. Hollywood Boulevard from one end to the other needs to be redone. The corner of Hollywood and Vine—nobody knows that famous corner, but to me, it’s the most famous corner in the world—even more than 42nd Street in Times Square, or the Champs-Élysées in Paris, or Piccadilly Circus in London. People should know Hollywood and Vine is the heart of the world. There is a statue at the corner of Beverly Boulevard and Olympic Avenue in Los Angeles, not far from where I live. The statue is about twenty feet tall, all in bronze. It is a scroll of film going up and up into the air with pictures in the frames of Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin and others, indicating who had created Hollywood. A duplicate of that statue, twice its size, all in gold, should be at the corner of Hollywood and Vine, lit by spotlights from every corner. That way, when people arrive and see that statue for the first time, they know they are at the center of the city that influenced the whole world. Along the way, we should relight all the theaters along Hollywood Boulevard and put the names of all the famous films that first appeared in them. In the lobbies of these magnificent old palaces, there should be brief histories and photographs of the movies that premiered there, way back in 1928 and 1932 and 1939. This would turn Hollywood Boulevard into a museum of film history as you walked all along it. One theater could be open all day showing the cartoons of Chuck Jones and Walt Disney. Another theater could be open all day showing all the old classics.

And there is one last thing very late in time, one last building I would like to work on.

What is it? you ask. Why, a library of course. We should build a library with a great Egyptian mummy out front, a Tutankhamun statue, and his mouth opens and speaks to you, asking, “Where would you like to go in the library?” You tell the mummy where you want to go. There is a front door, of course, but for the young and the young at heart, he sends you down a rabbit hole into the library. When you slide down and arrive, there are books all around and by every shelf there is a different mummy and you speak to them and ask, “What’s on this shelf?” and it tells you. And you say, “I want to go to the stars,” and the mummy says, “In the back of the library there is a spiral staircase that goes up to the stars.” And you climb the stairs and arrive at the top among books on astronomy and you are surrounded by stars. There is a glass window on the ceiling, a moonroof, looking out at the sky. So when you are in the room at night, you can read books about the stars, at least partially, by starlight.

As I look back over the last fifty years of my work in architecture, I can’t help but think about the time I visited the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago in 1933. I was twelve, and as I wandered about that incredible city they had constructed, I fell in love with the future. And after I left the fair, I went home to the small Illinois town where I lived and in the backyard of my parents’ home, I constructed buildings out of paper and cardboard, not knowing that thirty years forward, in my own future, I would start my architectural work helping to build another World’s Fair, the 1964 New York World’s Fair, thus beginning my career as the world’s only accidental architect.

This essay appears in Ray Bradbury: The Last Interview and Other Conversations, out this month. Reprinted with permission of Melville House.

Ray Bradbury (1920–2012) is the author of twenty-seven novels, including Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, and more than six hundred short stories. Bradbury won many awards throughout his lifetime, including the Grand Master Award from the Science Fiction Writers of America and a National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

Sam Weller is the author of The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury and Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews, and the coeditor of Shadow Show: All-New Stories in Celebration of Ray Bradbury, which won a Bram Stoker Award. Weller is an associate professor in the department of Creative Writing at Columbia College Chicago.

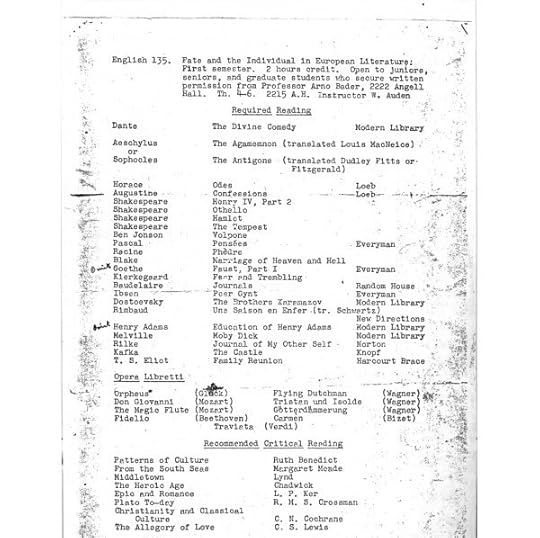

W. H. Auden’s Potent Syllabus, and Other News

Light reading. Image via More Than 95 Theses

W. H. Auden was a professor at the University of Michigan for the 1941–42 academic year. His course was called Fate and the Individual in European Literature, and its syllabus mandated more than six thousand pages of reading: The Divine Comedy, The Brothers Karamazov, Moby-Dick, Fear and Trembling …

Coming to the Huntington Library: Jane Austen’s family letters, Wicked Ned the Pirate’s watercolors, Louis Pasteur’s beer notes (“scribbled on pages of various sizes, in black and blue ink”).

On Pedro Lemebel, a Chilean writer (and artist and activist and provocateur) who died last week: “a writer who called himself a ‘queen’ (una loca) and ‘a poor old faggot’ (un marica pobre y viejo), and whose style and obsessions were forged on the social margins and in political opposition.”

Alfred Hitchcock’s unreleased documentary about the Holocaust, suppressed for decades, is being screened in full for the first time later this year. “The film, shown at test screenings, extremely disturbed colleagues, experts and film historians.”

Fear death? Sure you do! Don’t just sit there drumming your fingers and waiting for the end, though. Talk about it. Over coffee. At a Swiss death café. “The idea for the café mortel was simple: the gathering was to take place in a restaurant, anyone could come, and [Bernard] Crettaz [a Swiss sociologist] himself would gently marshal the conversation. The only rule was that there was to be no prescription: no topic, no religion, no judgment. He wanted people to talk as openly on the subject as they could.”

January 28, 2015

Speaking Bluntly

Colette in 1907.

Two letters from Colette, who was born on this day in 1873, to her friend Marguerite Moreno.

Rozven, mid-September 1924

… I should like to talk earnestly to you about your copy for Les Annales. You still do not have quite the right touch. You lack the seeming carelessness which gives the “diary” effect. For the most part you have approached your gentlemen as though they were so many subjects assigned in class … For one portrait which works—Jarry—there are two others—Proust and Iturri, say—who don’t. They are just not sufficiently alive!

I am speaking to you now just as bluntly as I would speak to myself … You, who are magic itself when it comes to oral storytelling, lose most of your effects when you come to write. You leave out the color. For instance, your Proust—pages 3, 4, 5. If you were talking to me, this scene would be stunning. But in your written version what do I find? “Madame A. had a critical mind and brought ruthless judgments to bear … a chorus of flatterers agreed … the conversation took a bitter turn … mocking exclamations, derisive remarks,” etc. Do you realize that in all that not one word makes me see and hear what you’re talking about? If you were telling me this in person, you would paint old Madame A. and her husband, Papa Anatole France, and the whole company in fifteen lines. You would transform your “untethered mischiefmaking” into a single line of dialogue, of heard conversation, and it would all come alive. No mere narration, for God’s sake! Concrete details and colors! And no need of summing up! I don’t give a damn whether or not you ask Proust’s pardon for having misunderstood him. Nor do I care whether or not Sardou was “one of the kings of the contemporary stage”! Do you see? And the same goes for Iturri. A “charming and delicate dinner party”—“a conversation which wandered from one subject to another”—what are you showing me with phrases like these? But nothing! Paint me a décor, with real guests and the food they are eating! Otherwise, it’s all dead! In spite of yourself, you’re thinking of Madame Brisson. And I forbid you to do so! Liberate yourself! And try, oh my dear heart, do try to conceal from us the fact that you loathe writing. Try also to pardon me for throwing all this on paper so hastily. I must dash. Write me at Blvd. Suchet. I love you, I hug you, and I am determined that you shall write “marvelous” things, do you hear? My paw to Pierre.

Paris, June 14, 1926

I’m told you’ve been working ten hours a day and I hope this isn’t true. If it is, I cannot sympathize enough. Scratching paper is such a somber battle. There are no witnesses, no one else in your corner, no passion. And all the while, waiting outside, there are your blue spring, the very cries of your peacocks, and the fragrance of the air. It’s very sad.

Translated from French by Robert Phelps, 1980

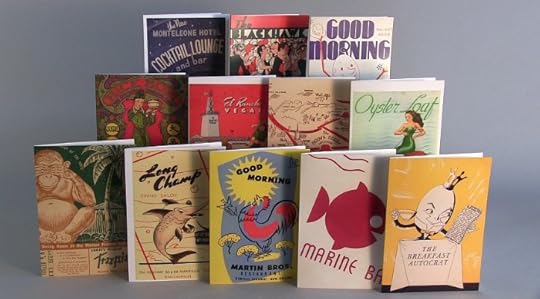

Good News

Photo: Bonnie Slotnick Cookbooks

Today, fans of the Bonnie Slotnick Cookbooks store received a welcome e-mail. “Bonnie Slotnick Cookbooks—MOVED!!” read the triumphant subject line. After being forced to leave its longtime home on West Tenth Street, and facing an uncertain future, the beloved institution has landed safely in a new location in the East Village. Many who love the terrific antiquarian shop—stocked with centuries’ worth of culinary history, lore, and recipes—and its knowledgeable owner have breathed a sigh of relief.

Especially in cities, we’re all so used to seeing independent businesses and brick-and-mortar bookstores die—we’re almost inured to it—that it feels strange to get good news. Usually, we give our heads a mournful shake and think, Well, it was too good to last. But, thanks to the generosity of a pair of siblings who are providing a great space at an affordable rent, the shop will not merely survive, but enjoy three times its old space, plus a garden. As Bonnie wrote in an earlier e-mail, “What Margo and Garth [the aforementioned siblings] have done is extraordinary in this day and age, and especially in this city.”

The 28 East Second Street location promises to be up and running by early February; do go by if you can. As Bonnie writes, “I’m looking FORWARD. CHANGE IS GOOD! Repeat after me: CHANGE IS GOOD!” (Well, occasionally, anyway.)

Confoundingly Picturesque

On the obsolescence of guidebooks; traveling in Myanmar.

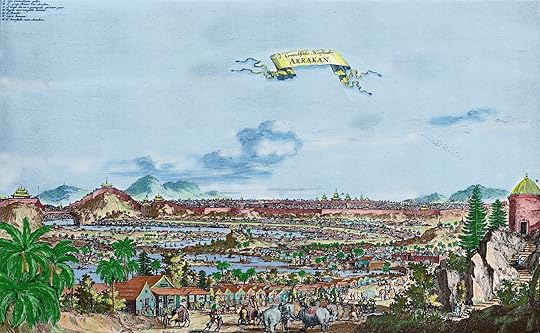

A Portuguese engraving of Mrauk U, 1676.

Several years ago in New York, I told Wim Wenders how much I’d liked his film about musicians in Lisbon; he grabbed me by the lapels. “You should go,” he said, “before it’s too late.” I didn’t go then. A few years later I did, and I couldn’t tell whether it was too late. Probably it was—that seems to almost always be the case.

In a similar mind, I went to Myanmar. “It’s already too late” is the refrain one hears again and again about Myanmar, but better late than never. Flights from Bangkok to Yangon are ridiculously cheap, but the city that was Rangoon has a hotel shortage, and beds there are not. Even the taxi from the airport reveals a city in the throes of sudden, extreme development: Vaguely worded business parks have sprouted up everywhere and billboards promise luxurious condos. Hotel lobbies have fliers from real estate developers; breakfast is a sea of laptops, people trying to get in on the ground floor of a newly opened country.

In the hands of Westerners everywhere in Myanmar, one notices a book—Lonely Planet’s Myanmar (Burma), published in July of last year, the most recent travel guide to the country. Leave the capital and its prevalence is even more striking. Elsewhere, the travel guide is a vanishing species, done in first by the Internet and then by smartphones. In most countries in the region, a ten-dollar SIM card will get you Google Maps, Wikipedia, TripAdvisor, Agoda; even without a SIM, wireless isn’t hard to find. Myanmar, for the moment, is different. You can buy a SIM in Yangon, but we left for Sittwe the day after the electrification of Rakhine State was celebrated: asking for a working cellular network there was too much too soon. Lonely Planet would have to suffice.

From Sittwe we took a boat for five hours up the Kaladan River, arriving at Mrauk U, pronounced “mraw ooh,” once the mighty capital of the kingdom of Arakan, now mostly forgotten by those outside of Myanmar. Electrification’s effects on Mrauk U are mostly theoretical. A good proportion of the local population appears to be occupied by breaking rocks into smaller rocks so that they might have paved roads, which will presumably make getting to Mrauk U a simpler process than it is now. The travelers one sees there are mostly Germans, many of them visibly miffed that we’d brought our daughter somewhere so seemingly remote as to be at the very end of the Lonely Planet. If a three-year-old’s there, it must be too late.

Even if it’s no longer undiscovered, Mrauk U is still deeply confusing. The city is full of ancient pagodas and Buddha images. How old they are is difficult to tell, not least because they’re regarded not as ruins but as part of an ongoing religious tradition. Collapsed structures have been rebuilt; Buddha images said to be ancient and made from sandstone have been repainted so many times that they appear identical to more recent plaster Buddhas. A monastery’s museum contains ancient figurines, old coins, the remains of a blown-up and popped puffer fish, and Sony cassette tapes in their original packaging. Paintings that bear a strong resemblance to Mexican retablos show perplexing scenes: a frog eating a snake, a demon hammering a stake in the ear of a woman, a horse with two heads. Captions in Burmese don’t help—the locals smiled and nodded, but I didn’t understand what I was seeing.

The Lonely Planet doesn’t explain these things—it can’t, really, when it only has five pages for the town. In one of the pagodas, I was happy to find a locally produced guidebook Famous Monuments of Mrauk-U (Useful Reference for Tourists and Travelers) by Myar Aung, translated into English by Ah Lonn Maung. It’s a helpful book, though occasionally perplexing: one learns, for example, the etymology of the town’s name:

As regards the name of the city, i.e. Mrauk-U, there are different assumptions. One is that when the Taungnyo and Kokka hills were being levelled to erect the palace, a monkey was found guarding the golden egg of the pea-hean, signifying Myauk (monkey) and “U”, (pronounced “Oo”) signifying the egg; thus “Myauk-U”. Another theory holds that the site where the city was founded was home to “earth-goddess” Mrauk-U. Still holds another belief that the city site lies to the northward of Laung-kret, the old royal city. (sic)

And one learns of the eight wonders of a certain Buddha image:

No animal and no bird dares to pass or fly over, jump or rest on the tired-roof of the special chamber in which Mahamuni Image has been housed.

The face of Mahamuni Image always enamates aureole of colourful hues like the full moon just coming out.

The face turns brownish blue when the infidel looks at it.

The exact likeness of the Image could not be casted.

Suffering is faced in practical terms whenever a person lies in judicial dispute.

Proportionate bodily structure is maintained through gilding by the devotees is made daily.

Being crowded with the devotees all the year round.

No water remains on the Image though water be poured on it in Tagu, Kason months of Rakhine calender as well as in New Year celebrations.

It’s a lovely book, slightly amateur but with a clear heart and a desire to teach the befuddled traveler. I like this kind of book more than I should. My shelves are crowded with out-of-date guidebooks. My copy of Ahmed M. Ashiurakis’s 1977 Guide to the Libyan Jamahereya will never help a potential traveler, but once, theoretically, it could have.

* * *

On my travels, I brought along the Library of America volume of the early Henry James novels—The American and The Europeans, of course, but also the ones than no one ever reads: Watch and Ward, Roderick Hudson, and Confidence, a novel so unloved that its title is erroneously prefixed with The on this edition’s title page. The ridiculousness of reading Henry James while on a Burmese river goes without saying, of course. But it’s hard not to see oneself reflected in James’s idiot Americans mooning about Europe. In Roderick Hudson, the diligence of one character, Mary Garland, is signaled by her immersion in a book. At the Vatican:

He had been watching, once, during some brief argument, to see whether she would take her forefinger out of her Murray, into which she had inserted it to keep a certain page. It would have been hard to say why this point interested him, for he had not the slightest real apprehension that she was dry or pedantic. The simple human truth was, the poor fellow was jealous of science. In preaching science to her, he had over-estimated his powers of self-effacement. Suddenly, sinking science for the moment, she looked at him very frankly and began to frown. At the same time she let the Murray slide down to the ground, and he was so charmed with this circumstance that he made no movement to pick it up.

Again on the Palatine:

The day left a deep impression on Rowland’s mind, partly owing to its intrinsic sweetness, and partly because his companion, on this occasion, let her Murray lie unopened for an hour, and asked several questions irrelevant to the Consuls and the Cæsars.

And at the Galleria Borghese:

Miss Garland was wandering in another direction, and though she was consulting her catalogue, Rowland fancied it was from habit; she too was preoccupied. He joined her, and she presently sat down on a divan, rather wearily, and closed her Murray.

“Her Murray” is Murray’s Handbook for Travellers on the Continent, a British travel guide published beginning in 1836. Four decades later, when James published Roderick Hudson, carefully reading guidebooks had become a duty of the traveler already tiresome: Rowland Mallet, secretly enamored of Mary Garland, waits again and again for her to grow weary of her book. Mallet is a seasoned traveler living in Rome. He doesn’t need a guidebook. Mary, by reading hers, hopes to become something she’s not.

There might be something quintessentially American about what her behavior reflects—a belief that the travel guide might not be that far removed from the genre of self-help, transforming a plain woman from Northampton (much of the humor in Roderick Hudson comes from jokes about how backwards Northampton is) into an educated woman who can hold her own with cultured Europeans and expatriates.

And this gets, perhaps, to what’s always seemed somewhat suspect about the guidebook as a form: the presumption that it’s a key, a vade mecum, that will instantly unlock a city or a country. The promise of a shortcut to knowledge.

* * *

Murray’s Handbook got its start just before the better-known Karl Baedeker sent Germans tromping all over the world, something irksome to the Anglophone traveler by the time James wrote Confidence in 1880. Bernard Longueville realizes that he’s at the wrong hotel in Siena:

If he had gone to the other inn he might have had charming company: at his own establishment there was no one but an æsthetic German who smoked bad tobacco in the dining-room.

Though Germans remained more industrious travelers, Murray’s Handbook would soldier on, turning into the Blue Guides in 1915; though the Blue Guides have seen better days, they’re still, amazingly, being published. They don’t cover Mrauk U, though Murray’s once did. A page from the end of the section on Burma in the eighth edition of Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in India, Burma, and Ceylon, published in 1911, has this to say about Mrauk U:

A pleasant excursion may be made to Myohaung, the ancient capital of Arakan, 50 miles up the Kaladan river, where the remains of the old town are still to be seen. For a description of them reference may be made to the reports of the later Dr Forchhammer, which were issued by the Burma Government Press in 1891. The ruins of the ancient Fort, with traces of the massive city wall and the platform on which the old palace stood, and the Andaw Shitthaung and Dukhantein pagodas, with their dark passages, images, and inscriptions, and the Pittekataik or ancient depository of the Buddhist scriptures, are among the most interesting sights of the place.

The antiquarian will thus find that Myohaung is full of interest, as also, if he has time to visit it, the Mahamuni Pagoda, some 48 m. farther N. A trip may also be made by river steamer to Paletwa, the headquarters of the Arakan hill tracts district, which is inhabited by Chaungthas, Shandus, Kwemis, Chins, Mros, and other strange hill tribes.

The industrious traveler with an Internet connection can download E. Forchhammer’s Arakan (1891) from the Internet Archive, where my copy of Murray’s is from. Forchhammer was, more than two centuries ago, already bemoaning how it was too late for Mrauk U:

For the splendid temples of Mrohaung, built by the kings of the Myauk-ū dynasty, the natives have more superstitious awe than religious reverence; they seldom worship at these shrines and they allowed them to fall into disrepeair; while they contribute freely to plaster, whitewash, or gild the architecturally worthless Urittaung or the Sandoway pagodas, they will not raise a hand to prevent the wanton destruction, by treasure-hunters, of the temples, which bespeak the power, resources, and culture of their former rules. The architectural style of the Shitthaung and Dukkanthein pagodas is probably unique in India, and the two shrines are undoubtedly the finest ruins in Lower Burma.

Henry James suggests that it’s always too late for the traveler, who will never reach the desired destination. Roderick Hudson again:

It all was confoundingly picturesque; it was the Italy that we know from the steel engravings in old keepsakes and annuals, from the vignettes on music-sheets and the drop-curtains at theatres; an Italy that we can never confess to ourselves—in spite of our own changes and of Italy’s—that we have ceased to believe in.

And here, maybe, is the dilemma of the travel guide. A book, to be read, must be written in the past. But places, like people, unlike books, are constantly changing, and the travel guide is out of date the minute the pen is lifted from paper. One suspects that Lonely Planet isn’t long for this world, at least in print form: the admittedly infelicitous and unpredictably inaccurate sentences of Wikitravel are free everywhere an Internet connection can be had. The travel guide may join the Mrauk U that Forchhammer regrets, the Italy that exists only in memory, the Burma that everyone insists is vanishing. Against them we might poise the temples of Mrauk U, ancient ruins extending into the present, still worshiped by bemused locals who wonder at the waves of visitors.

Dan Visel lives in Bangkok and is writing a book on reading.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers