The Paris Review's Blog, page 619

February 6, 2015

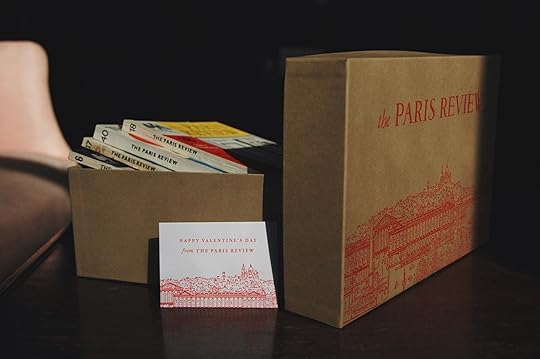

Visit Our Valentine’s Day Pop-up Shop on Thursday

Our gift boxes—and plenty of issues from our archive—will be available on Thursday.

You may have heard about our special Valentine’s Day gift box—choose any three issues from our archive, and at no extra charge, we’ll bundle them in the lovely package you see above, including a card featuring William Pène du Bois’s 1953 sketch of the Place de la Concorde.

If you’re downtown this Thursday, February 12, and you need a last-minute gift, you can pick up a Valentine Day’s set from us in person. We’re hosting a pop-up shop at the Standard Hotel’s Shop at the High Line: 848 Washington Street at Thirteenth Street. We’ll be there all afternoon with a wide array of vintage issues, discounted subscriptions, T-shirts, and more. Stop by and say hello! We’ll update this space with more details as we have them.

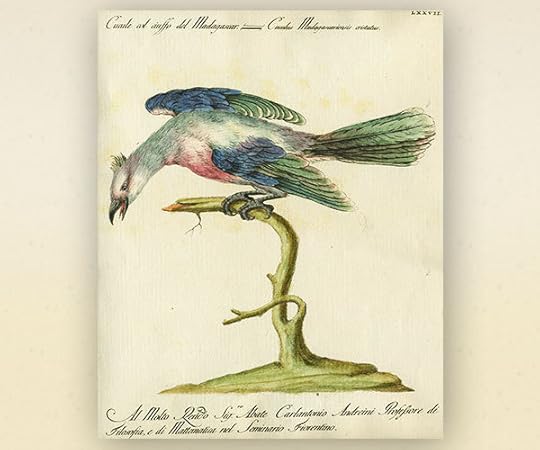

$190,000 Birds, and Other News

Image via AbeBooks

Latin, the most famous dead language, is enjoying another of its many posthumous lives: “A language can fall out of everyday use, its forms can cease to change, and yet writers will still use it to do new things. This happened to Sumerian and Hebrew—and it happened to Latin too. People all over the Mediterranean world and beyond continued to use Latin after Virgil and Cicero—and they did so in endlessly creative ways.”

The hazards of open endings: Why does so much literary fiction refuse to provide a real resolution? “An authorial strategy now so widespread to have almost become the norm in literary fiction was so ‘unfamiliar’ back in 1925 that Woolf suggested readers ‘need a very daring and alert sense of literature to make us hear the tune.’ ”

A 1765 book about ornithology has sold for $190,000: “Published in Florence in Italian in five volumes, it contains 600 beautiful hand-colored engraved plates of birds. Commissioned by Maria Luisa, the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, the book took ten years to complete … Some consider the book to be a commentary on 18th-century Italian high society because the bird poses are almost human.”

Technicolor turns 100: “We realize that color is violent and for that reason we restrained it,” an early adopter once said. But today, Technicolor has developed “this very vibrant, saturated palette ... When these films started getting more colorful, that's what audiences reacted to. They loved this artificial, fantasy, over-the-top palette. And that’s the way color shifted. It’s idealized.”

Running a bookstore is hard. Running an anarchist bookstore is even harder. And not because of the anarchy, it turns out—because of the antianarchy. At San Francisco’s Bound Together, “there’ve been plenty of adventures, like the time when the bookstore was threatened by Neo-Nazis in the eighties and members slept in the space nightly to protect it. There was also an attempted arson in the eighties, when someone dumped gasoline through the mail slot and tossed a lit match in to start a fire.”

February 5, 2015

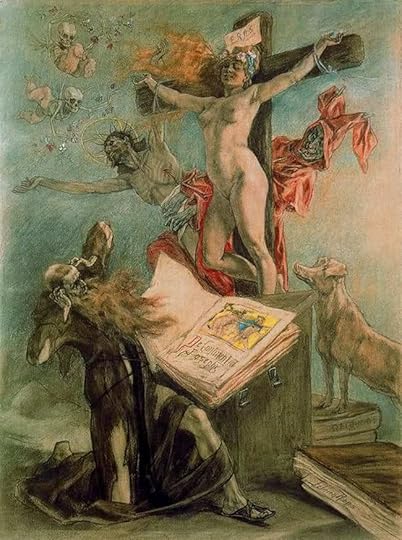

Divine Ordure

A master class in hailing Satan.

An illustration by Félicien Rops for a bootleg edition of Là-Bas.

“The odor from those incense burners is unbearable … What do they burn that smells like that?”

“Asphalt from the street, leaves of henbane, datura, dried nightshade, and myrrh. These are perfumes delightful to Satan, our master.”

When J. K. Huysmans published Là-Bas (Down There) in 1891, it caused an immediate scandal in France. Huysmans serialized the novel in L’Écho de Paris, a newspaper; readers wrote in early and often to express their revulsion, threatening to cancel their subscriptions if the serialization was not halted posthaste. Not long afterward, when the book itself came out, it was banned from sale at railway kiosks, thus ensuring that it loomed all the larger in the public imagination. Controversy followed the book abroad, too—no one bothered to attempt an English translation for more than thirty years, and even then, the U.S. Society for the Suppression of Vice ruled that it was simply too immoral to see the light of day.

The outrage stemmed from the book’s frank depiction of Satanism—it culminates in a Black Mass, vividly described. Its protagonist, a novelist named Durtal, has pursued his interest in the occult to its logical conclusion, and he’s startled to learn that a thriving underworld persists in contemporary Paris. Huysmans conducted extensive research for the novel, basically embedding himself among a group of Satanists; he was disenchanted with ordinary life, and he wanted literature to present a thrilling alternative to quotidian reality. But he went too far. He grew so distressed by the darkness and evil in Là-Bas—and, perhaps, in his own soul; the novel’s subtitle is “A Journey into the Self”—that he came to regard it as a black book; he wrote a white book, En Route, to cancel its negative energy. (It’s sort of the same way that Prince, a century later, recorded Lovesexy to exorcize the demons of The Black Album.) Later in life, Huysmans converted to Catholicism.

You can understand, if you read its most famous scene, why the novel provoked such a furor in public and author alike. It’s dark and capital-D Decadent, the product of fin de siècle fixations, when matters of the occult could not have been more portentous or profound. As the afterword to a recent edition says, “Huymans has given us spit-and-sawdust Satanism. His Black Mass and its aftermath still have the power to shock.” That’s true: what’s presented here is what one character in the novel calls “a veritable seraglio of hystero-epileptics and erotomaniacs.” It’s a terrifying bit of saturnalia, often so over-the-top as to seem satirical to a contemporary reader. There are parts of it I couldn’t help but laugh at, but—at least in Keene Wallace’s 1928 translation, presented here—it’s mainly a joy to read, because the forces of hate and evil have seldom been marshaled with such style. Here’s the beginning of the Mass:

Preceded by the two choir boys the canon entered, wearing a scarlet bonnet from which two buffalo horns of red cloth protruded. Durtal examined him as he marched toward the altar. He was tall, but not well built, his bulging chest being out of proportion to the rest of his body. His peeled forehead made one continuous line with his straight nose. The lips and cheeks bristled with that kind of hard, clumpy beard which old priests have who have always shaved themselves. The features were round and insinuating, the eyes, like apple pips, close together, phosphorescent. As a whole his face was evil and sly, but energetic, and the hard, fixed eyes were not the furtive, shifty orbs that Durtal had imagined.

The canon solemnly knelt before the altar, then mounted the steps and began to say mass. Durtal saw then that he had nothing on beneath his sacrificial habit. His black socks and his flesh bulging over the garters, attached high up on his legs, were plainly visible. The chasuble had the shape of an ordinary chasuble but was of the dark red color of dried blood, and in the middle, in a triangle around which was an embroidered border of colchicum, savin, sorrel, and spurge, was the figure of a black billy-goat presenting his horns.

Docre made the genuflexions, the full- or half-length inclinations specified by the ritual. The kneeling choir boys sang the Latin responses in a crystalline voice which trilled on the ultimate syllables of the words […] the choir boys passed behind the altar and one of them brought back copper chafing-dishes, the other, censers, which they distributed to the congregation. All the women enveloped themselves in the smoke. Some held their heads right over the chafing-dishes and inhaled deeply, then, fainting, unlaced themselves, heaving raucous sighs.

A feast for the senses. There’s something especially nauseous about “his flesh bulging over the garters,” especially with that stench in the air. But things really take off when the canon speaks directly to Satan himself, extolling the Father of Lies in great detail for the depth and variety of his perfidy:

“Master of Slanders, Dispenser of the benefits of crime, Administrator of sumptuous sins and great vices, Satan, thee we adore, reasonable God, just God!

“Superadmirable legate of false trances, thou receivest our beseeching tears; thou savest the honour of families by aborting wombs impregnated in the forgetfulness of the good orgasm; thou dost suggest to the mother the hastening of untimely birth, and thine obstetrics spares the still-born children the anguish of maturity, the contamination of original sin.

“Mainstay of the despairing Poor, Cordial of the Vanquished, it is thou who endowest them with hypocrisy, ingratitude, and stiff-neckedness, that they may defend themselves against the children of God, the Rich.

“Suzerain of Resentment, Accountant of Humiliations, Treasurer of old Hatreds, thou alone dost fertilize the brain of man whom injustice has crushed; thou breathest into him the idea of meditated vengeance, sure misdeeds; thou incitest him to murder; thou givest him the abundant joy of accomplished reprisals and permittest him to taste the intoxicating draught of the tears of which he is the cause.

“Hope of Virility, Anguish of the Empty Womb, thou dost not demand the bootless offering of chaste loins, thou dost not sing the praises of Lenten follies; thou alone receivest the carnal supplications and petitions of poor and avaricious families. Thou determinest the mother to sell her daughter, to give her son; thou aidest sterile and reprobate loves; Guardian of strident Neuroses, Leaden Tower of Hysteria, bloody Vase of Rape!

“Master, thy faithful servants, on their knees, implore thee and supplicate thee to satisfy them when they wish the torture of all those who love them and aid them; they supplicate thee to assure them the joy of delectable misdeeds unknown to justice, spells whose unknown origin baffles the reason of man; they ask, finally, glory, riches, power, of thee, King of the Disinherited, Son who art to overthrow the inexorable Father!”

Then Docre rose, and erect, with arms outstretched, vociferated in a ringing voice of hate:

“And thou, thou whom, in my quality of priest, I force, whether thou wilt or no, to descend into this host, to incarnate thyself in this bread, Jesus, Artisan of Hoaxes, Bandit of Homage, Robber of Affection, hear! Since the day when thou didst issue from the complaisant bowels of a Virgin, thou hast failed all thine engagements, belied all thy promises. Centuries have wept, awaiting thee, fugitive God, mute God! Thou wast to redeem man and thou hast not, thou wast to appear in thy glory, and thou sleepest. Go, lie, say to the wretch who appeals to thee, ‘Hope, be patient, suffer; the hospital of souls will receive thee; the angels will assist thee; Heaven opens to thee.’ Impostor! thou knowest well that the angels, disgusted at thine inertness, abandon thee! Thou wast to be the Interpreter of our plaints, the Chamberlain of our tears; thou wast to convey them to the Father and thou hast not done so, for this intercession would disturb thine eternal sleep of happy satiety.

“Thou hast forgotten the poverty thou didst preach, enamoured vassal of Banks! Thou hast seen the weak crushed beneath the press of profit; thou hast heard the death rattle of the timid, paralyzed by famine, of women disembowelled for a bit of bread, and thou hast caused the Chancery of thy Simoniacs, thy commercial representatives, thy Popes, to answer by dilatory excuses and evasive promises, sacristy Shyster, huckster God!

“Master, whose inconceivable ferocity engenders life and inflicts it on the innocent whom thou darest damn—in the name of what original sin?—whom thou darest punish—by the virtue of what covenants?—we would have thee confess thine impudent cheats, thine inexpiable crimes! We would drive deeper the nails into thy hands, press down the crown of thorns upon thy brow, bring blood and water from the dry wounds of thy sides.

“And that we can and will do by violating the quietude of thy body, Profaner of ample vices, Abstractor of stupid purities, cursed Nazarene, do-nothing King, coward God!” “Amen!” trilled the soprano voices of the choir boys.

I don’t see why thousands of heavy-metal lyricists haven’t borrowed or outright stolen this speech; it’s got to be one of the best encomia to pure evil ever put to paper. Mercyful Fate and King Diamond could learn a thing or two. From here, the scene descends into prurient chaos, as the women begin to succumb to epileptic fits that result conveniently in the loss of clothing:

Durtal listened in amazement to this torrent of blasphemies and insults. The foulness of the priest stupefied him. A silence succeeded the litany. The chapel was foggy with the smoke of the censers. The women, hitherto taciturn, flustered now, as, remounting the altar, the canon turned toward them and blessed them with his left hand in a sweeping gesture. And suddenly the choir boys tinkled the prayer bells.

It was a signal. The women fell to the carpet and writhed. One of them seemed to be worked by a spring. She threw herself prone and waved her legs in the air. Another, suddenly struck by a hideous strabism, clucked, then becoming tongue-tied stood with her mouth open, the tongue turned back, the tip cleaving to the palate. Another, inflated, livid, her pupils dilated, lolled her head back over her shoulders, then jerked it brusquely erect and belaboured herself, tearing her breast with her nails. Another, sprawling on her back, undid her skirts, drew forth a rag, enormous, meteorized; then her face twisted into a horrible grimace, and her tongue, which she could not control, stuck out, bitten at the edges, harrowed by red teeth, from a bloody mouth.

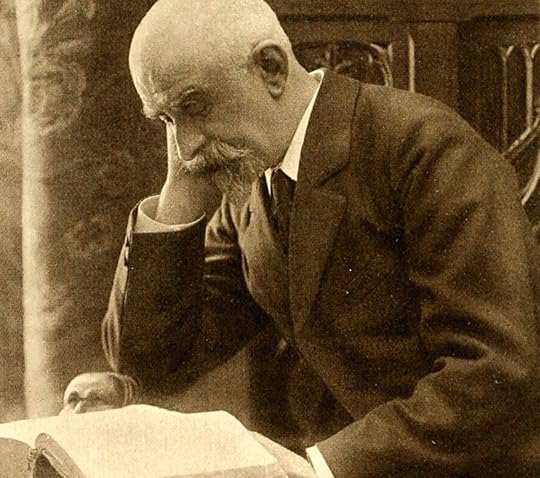

Huysmans, ca. 1895.

For the coup de grâce, Docre tosses the communion bread across the room, gets a hard-on, and initiates an orgy:

Docre contemplated the Christ surmounting the tabernacle, and with arms spread wide apart he spewed forth frightful insults, and, at the end of his forces, muttered the billingsgate of a drunken cabman. One of the choir boys knelt before him with his back toward the altar. A shudder ran around the priest’s spine. In a solemn but jerky voice he said, “Hoc est enim corpus meum,” then, instead of kneeling, after the consecration, before the precious Body, he faced the congregation, and appeared tumefied, haggard, dripping with sweat. He staggered between the two choir boys, who, raising the chasuble, displayed his naked belly. Docre made a few passes and the host sailed, tainted and soiled, over the steps.

Durtal felt himself shudder. A whirlwind of hysteria shook the room. While the choir boys sprinkled holy water on the pontiff’s nakedness, women rushed upon the Eucharist and, groveling in front of the altar, clawed from the bread humid particles and drank and ate divine ordure. […]

Another woman, curled up over a crucifix, emitted a rending laugh, then cried to Docre, “Father, father!” A crone tore her hair, leapt, whirled around and around as on a pivot and fell over beside a young girl who, huddled to the wall, was writhing in convulsions, frothing at the mouth, weeping, and spitting out frightful blasphemies. And Durtal, terrified, saw through the fog the red horns of Docre, who, seated now, frothing with rage, was chewing up sacramental wafers, taking them out of his mouth, wiping himself with them, and distributing them to the women, who ground them underfoot, howling, or fell over each other struggling to get hold of them and violate them.

The place was simply a madhouse, a monstrous pandemonium of prostitutes and maniacs. Now, while the choir boys gave themselves to the men, and while the woman who owned the chapel, mounted the altar caught hold of the phallus of the Christ with one hand and with the other held a chalice between “His” naked legs, a little girl, who hitherto had not budged, suddenly bent over forward and howled, howled like a dog. Overcome with disgust, nearly asphyxiated, Durtal wanted to flee. He looked for Hyacinthe. She was no longer at his side. He finally caught sight of her close to the canon and, stepping over the writhing bodies on the floor, he went to her. With quivering nostrils she was inhaling the effluvia of the perfumes and of the couples.

“The sabbatic odor!” she said to him between clenched teeth, in a strangled voice.

“Here, let’s get out of this!”

She seemed to wake, hesitated a moment, then without answering she followed him. He elbowed his way through the crowd, jostling women whose protruding teeth were ready to bite. He pushed Mme. Chantelouve to the door, crossed the court, traversed the vestibule, and, finding the portress’ lodge empty, he drew the cord and found himself in the street.

It should end there, but Hyacinthe lures Durtal into a spiral staircase, and soon they’ve adjourned to “a musty room” to make love, or hate, or something:

The paper was peeling from the walls, which were nearly covered with pictures torn out of illustrated weeklies and tacked up with hairpins. The floor was all in pieces. There were a wooden bed without any curtains, a chamber pot with a piece broken out of the side, a wash bowl and two chairs.

The man brought a decanter of gin, a large one of water, some sugar, and glasses, then went downstairs.

Her eyes were sombre, mad. She enlaced Durtal.

“No!” he shouted, furious at having fallen into this trap. “I’ve had enough of that. It’s late. Your husband is waiting for you. It’s time for you to go back to him—”

She did not even hear him.

“I want you,” she said, and she took him treacherously and obliged him to desire her. She disrobed, threw her skirts on the floor, opened wide the abominable couch, and raising her chemise in the back she rubbed her spine up and down over the coarse grain of the sheets. A look of swooning ecstasy was in her eyes and a smile of joy on her lips.

She seized him, and, with ghoulish fury, dragged him into obscenities of whose existence he had never dreamed. Suddenly, when he was able to escape, he shuddered, for he perceived that the bed was strewn with fragments of hosts.

I think we’re inured against the shock of this kind of writing—but as a set piece, it’s unbeatable. If anyone can direct me to a depiction of Satanism on par with this one, please do.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

What About Bob

Shelley Duvall in the TV adaptation of “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” 1976.

Bernice stood on the curb and looked at the sign, Sevier Barber-Shop. It was a guillotine indeed, and the hangman was the first barber, who, attired in a white coat and smoking a cigarette, leaned non-chalantly against the first chair. He must have heard of her; he must have been waiting all week, smoking eternal cigarettes beside that portentous, too-often-mentioned first chair. Would they blind-fold her? No, but they would tie a white cloth round her neck lest any of her blood—nonsense—hair—should get on her clothes.

“All right, Bernice,” said Warren quickly.

With her chin in the air she crossed the sidewalk, pushed open the swinging screen-door, and giving not a glance to the uproarious, riotous row that occupied the waiting bench, went up to the fat barber.

“I want you to bob my hair.”

The first barber’s mouth slid somewhat open. His cigarette dropped to the floor.

“Huh?”

“My hair—bob it!”

Before I had nearly a foot of my hair shorn off, I reread F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” He based the story, which first ran in the May 1920 Saturday Evening Post, on a series of letters he exchanged with his younger sister. It was, appropriately, the kickoff to his iconic chronicling of the flapper era—when the story begins, the eponymous heroine is a dowdy wallflower, and everyone has long hair. Bernice becomes popular with an audacious “line”: she entices boys with the prospect of daringly bobbing her hair while they watch. But when a rival calls her bluff, Bernice is forced to submit to the shears. And then, the brutal fallout.

The story plays with ideas of virtue and symbolism, invoking everything from Samson to Berenice of classical legend. That she casts off her scruples with her tresses is no accident; and that the tease of danger is more alluring to the boys than the actual breaking of convention comes as little shock to the reader.

What I wanted from my haircut was a cross between Zelda Fitzgerald and Donna Hayward. And, of course, now you can do that: pull a few pics up and a change that would have rattled a ballroom full of 1920s Minnesotans garners nothing more than a few obligatory Instagram compliments. Everything’s a reference. Someone smart said not long ago that the difference between serious fiction and the other sort is whether or not the secondary characters function as more than wish fulfillment for a protagonist. Whether or not you believe that’s true, it’s interesting food for thought.

In short, this is not the story to read before undergoing a major change to one’s hair, however many bobs Fitzgerald may have ultimately inspired. And if you really want to see the sinister underpinnings, by all means seek out the 1976 TV adaptation: it stars Shelley Duvall and Bud Cort. (If nothing else, her hair looks great.)

The Way the World Ends

Being the last man on Earth.

From In the Mouth of Madness, 1981.

On a recent Sunday evening, trying to relax, I turned on the television and saw an ad for a new comedy series called The Last Man on Earth. It wasn’t clear how everyone else had died.

I had learned what I needed to know, or had remembered it: television does not relax me. I turned the television off, took an Ativan, and listened to The Teddy Charles Tentet, a terrific jazz record.

Phil Miller is the last man on earth—which makes him the world’s greatest handyman—world’s greatest athlete—[etc.]

The last man on earth.

But of course one is not the Last Man on Earth. There are other people, equal claimants to the Earth. It can be vexing to share it with them.

*

The Last Man on Earth, 1964. Crumpled bodies, emptied streets. A sign reads: COMMUNITY CHURCH THE END HAS COME; Vincent Price speaks: “I own the world. An empty, dead, silent world.”

A plague has slain all of humanity—all but Price, as Richard Morgan. The afflicted went blind before dying. The government insisted on burning the corpses to slow contagion. Morgan’s daughter died, and her body was thrown into the pit at the edge of town and burned. When his wife died, he hid her body and buried it. That was how he learned the dead come back. It is a vampire plague, and each night after dark, Morgan’s former friends and neighbors hammer at his windows: “Morgan, come out. Come out.”

By day, Morgan methodically hunts for and slays sleeping vampires and drags as-yet unresurrected bodies into the pit to burn. By night, he listens to records and defends his home with garlic and mirrors: “They can’t bear to see their image,” he says in a voice-over. “It repels them. I need more mirrors. And this garlic’s lost its pungency.”

Morgan falls asleep in the community church and must fight his way home after dark through crowds of incompetent vampires. Once inside, he reminisces about his wife by watching old film reels of good times they had. He laughs until he cries. We see the happy times, the birthday party and the children playing together, the worldwide spread of the disease, the blindness and surprisingly affecting deaths of Morgan’s neighbors and his own daughter: “Mommy, where are you? Mommy, I can’t see. Mommy … Mommy, help me. Mommy. Mommy, please help me … Mommy. Mommy. Mommy, where are you?”

Why “surprisingly affecting”? Because this movie is shit. Which is not to claim that shit is not interesting. We eat, food nourishes our bodies, shit is a byproduct of that process that gives certain indications. Fecal occult blood tests are an important diagnostic tool. Let’s get into the bullshit and see what the bull ate.

From The Last Man on Earth, 1964.

Morgan finds dead vampires with strange stakes in their bodies, not manufactured by him. He decides other humans must exist. “Where did they come from? Where are they hiding? Why haven’t I seen them?”

Burying a dog on the outskirts of town, he meets another human, Ruth Collins. She is infected, but she and her community have found a way to hold the illness at bay with a vaccine. So there are three kinds of last men on Earth: vampires who spread disease, half-vampires who manage their illness and slay evil vampires, and Richard Morgan, an uninfected singleton, who is surprised to discover that he has been killing them all indiscriminately.

You’re a legend in the city, moving by day instead of night, leaving as evidence of your existence bloodless corpses. Many of the people you destroyed were still alive. Many of them were loved ones of the people in my group.

Collins, armed, has been sent to keep Morgan in place while her group attacks his house to kill him—tonight. “You can’t join us,” she tells him. “You’re a monster.” Attempting to prove his worth, Morgan uses his immunity to create a new vaccine for the half-infected Collins. Now she can tolerate garlic and she can face herself in the mirror.

Look. Look! You see? It worked, Ruth. The antibodies in my blood worked. My blood has saved you, Ruth. Do you know what this means? You and I can save all the others.

But it’s too late to call off the scheduled attack. Morgan is pursued by his half-human assailants through the streets. “There he is—in the church!” Wounded, he rails at them: “You’re freaks. All of you. All of you. Freaks, mutations. You’re freaks. I’m a man. The last man!”

He is killed on the altar of the community church. It is unclear whether his last words express puzzlement or pride: “They were afraid of me.”

From The Omega Man, 1971.

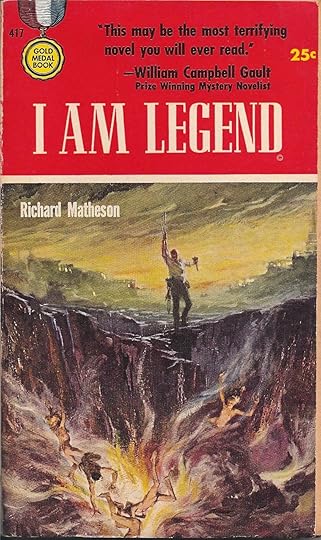

1971’s The Omega Man is, like The Last Man on Earth, based on Richard Matheson’s 1954 story “I Am Legend,” on which more shortly.

Charlton Heston is Robert Neville. Again the lonely watching of the film of happiness and community: this time it’s not home movies of children at a birthday party, but the Woodstock documentary. Again the rush home, combat with the infected adversaries. Again the flashback that explains the plague. This time it’s germ warfare: “Abort firings. Interception will fragment bacilli-carrying missiles.”

Again the sounds of group laughter from outside, calling him to join, and again the refusal. “Neville.” “Shut up! Why the hell can’t you leave me alone?”

The Omega Man is more straightforward than The Last Man on Earth about what membership in groups means, reminds us of, and feels like. This is a melodrama, with a hero and a villain—Matthias, leader of the infected Family. “The Family is one … Neville will come down, down to the Family and to judgment,” he says. “Outside the Family, there is nothing at all.”

The Family captures Neville and puts him on trial. “Does he have a family? Is he of the sacred society? Then what is he?” Neville is what the Family does not wish to know. “You are the angel of death, doctor, not us … and when you die, the last living reminder of hell will be gone.” The Family assigns the role of “knowledge-of-the-past” to Neville and seeks to destroy that knowledge, in a comically obvious way: they aim to immolate him on a pile of paintings and books.

A band of half-infected survivors rescue Neville from being burnt alive by the Family, and he explains himself to them.

Neville: I don’t have it.

Lisa: Have what?

Neville: The plague. I’m immune.

Dutch: Everybody has it!

Neville: Everybody but me. There was a vaccine … My blood might be a serum. The stage that boy’s in, my antibodies could reverse the whole process, stop it.

Dutch: Christ, you could save the world.

And, as if that weren’t Christified enough:

Child: They say the Family comes in the night when it’s dark. They say they’re going to come some night and take Ritchie’s soul, and tie it all up in a bag, and give it to the Devil. Is that really true? Do you know if that’s really true?

Neville: Oh, we wouldn’t let that happen. Not a chance.

Child: Are you God?

And if that still weren’t enough, in the end Neville dies in a fountain of his own healing blood, pierced by a spear in his side and hanging from a sculpture, no old rugged cross having been available from the props department.

*

These murders in churches, these fantasies of saving by the blood, are not accidental; they are intrinsic to the fantasy of The Last Man on Earth. They are the fantasy itself.

The alpha animal, who is subordinate to none, and the omega animal, who is dominant over none … The highest-ranking individual is the alpha animal; the lowest-ranking, the omega animal.

—Klaus Immelmann and Colin Beer’s Dictionary of Ethology, 1992

I am the first, and I am the last; and beside me there is no God.

—Isaiah 44:6

I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last.

—Revelation 22:13

A film called The Last Man on Earth or The Omega Man could only be an apocalypse scenario film. ΑΠΟΚΑΛΥΨΙΣ is the original Greek for the book we call Revelation.

Sometimes we ask, What would Jesus do? But we know the answer. He would be the alpha male and the omega man, both king and scapegoat. He would take on the sins of the world, then die, saving the world with his blood, and be resurrected in glory. But Jesus could do magic tricks because he was God in a beautiful story, and you aren’t God and this is reality, so try to relax.

From The Last Man on Earth, 2015.

“It has been a very fun show to shoot,” said Will Forte, star of the new TV show The Last Man on Earth, “because I get to do a lot of wish fulfillment.” But what are these wishes, and how have they been fulfilled?

The fantasy of complete destruction of the world does not include oneself … precisely because it is accomplished for the sole benefit of the self. The subject remains alone, united with the earth … The aim is to empty the mother’s body in order to totally occupy it oneself, thus regaining one’s place within … The contents of the body are so many obstacles to be swept away in order to reestablish the once perfect union with the mother. Because the contents of the mother’s body represent reality, this wish to rid her body of its contents is of a very crucial nature: destruction of these contents amounts to the destruction of reality … a mysterious domain: the human wish to destroy reality and to be one with the Mother once more.

—Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel, “A Short Essay on the Apocalypse,” 1988

*

My favorite last-man-on-earth film is John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness, from 1994: a horror movie about a man, John Trent, who goes mad and is locked in a padded cell when he realizes he’s not in control of his life, but is really a character in an horror story written by Sutter Cane.

Cane’s supernatural fictions are, in turn, not written by him but by otherworldly creatures that control him: “It’s funny, isn’t it? For years, I thought I was making all this up. But they were telling me what to write. Giving me the power to make it all real. And now it is. All those horrible, slimy things trying to get back in—they’re all true.” His horror stories drive the people who read them insane, and his latest best seller, reaching his widest readership ever, will soon cause the apocalypse.

Trent tells Cane’s editor, Linda Styles, that he, like Cane, has contempt for humanity and doesn’t mind if the earth is destroyed:

Trent: Believe me, the sooner we’re off the planet, the better.

Styles: Now you sound like Cane.

Trent: No, not me. You’re the Cane lover.

Styles: I just like being scared. Cane’s work scares me.

Trent: What’s to be scared about? It’s not like it’s real, or anything.

Styles: It’s not real from your point of view, and right now reality shares your point of view. But what scares me about Cane’s work is what might happen if reality shared his point of view.

Trent: Whoa, whoa, whoa. We’re not talking about reality here. We’re talking about fiction. It’s different.

Styles: Oh, reality is just what we tell each other it is. Sane and insane could easily switch places if the insane were to become the majority. You would find yourself locked in a padded cell, wondering what happened to the world.

Trent: No, that wouldn’t happen to me.

Styles: It would if you realized everything you ever knew was gone. That’d be pretty lonely—being the last one left.

John Trent transparently is the horror-writer Sutter Cane: horrified by responsibility, by the realization that he is, in most cases, the author of his own life, Trent disowns his self-authorship and projects it into an author-adversary, Cane, who can be opposed, though never defeated. Trent is so horrified by his responsibility for his own life, and by the unending competition with his fellow human beings for control over our shared reality, that he uses Cane’s creative powers to destroy the offending world—by making it insane or unsanitary, by eating it all and reducing it to shit.

The last scenes are in a deserted city, with no other group members. On this vacant and destroyed Mother Earth, all is undifferentiated unity with the dead mother (“all those horrible, slimy things trying to get back in”) in a cruel fable of granted wishes.

In the Mouth of Madness ends with Trent watching the film adaptation made from the book of his life. “I’m God now,” says Cane, “you understand?” The Last Man on Earth stares at his own image, his own reflection, and laughs until he begins to sob.

*

The first edition of I Am Legend, 1954

By now we know the basic scenes from Richard Matheson’s story I Am Legend.

He sat in the living room, trying to read. He’d made himself a whisky and soda at his small bar, and he held the cold glass as he read a physiology text. From the speaker over the hallway door, the music of Schönberg was playing.

Not loudly enough, though. He still heard them outside …

It was the women who made it so difficult, he thought, the women posing like lewd puppets in the night on the possibility that he’d see them and decide to come out.

He sat staring moodily at the bookcase, listening to Brahms’ second piano concerto, a whisky sour in his right hand, a cigarette between his lips.

Neville would rather stay at home with something in his mouth to suck on than go outside and play and fight on the social battleground. Oral cravings, oral violence—mouths of madness:

I’m an animal! he exulted. I’m a dumb, stupid animal and I’m going to drink! …

He drank directly from the uptilted bottle, gulping furiously, hating himself, punishing himself with the whisky burning down his rapidly swallowing throat.

I’ll choke myself! he stormed. I’ll strangle myself, I’ll drown myself in whisky!

When Neville is captured by the half-infected survivors, a woman takes pity on him and spares him public execution—how else?—by offering him, as Death-Mother, her poisoned breast.

She reached up quickly and unbuttoned her blouse. Reaching under her brassiere, she took out a tiny packet and pressed it into his right palm.

“It’s all I can do, Robert,” she whispered, “to make it easier. I warned you, I told you to go.” Her voice broke a little. “You just can’t fight so many, Robert.” …

He thought, I’m the abnormal one now. Normalcy was a majority concept, the standard of many and not the standard of just one man.

*

All of this raises certain questions about our leaping-off point, a new comedy series called The Last Man on Earth. It is not obviously the stuff of comedy. Comedy celebrates love and friendship, joining a community and adding to it, eros, union, reproduction, social binding and incorporation. The Comedy of Errors: “We came into the world like brother and brother; And now let’s go hand in hand, not one before another.” Measure for Measure: “What’s mine is yours, and what is yours is mine.” The Two Gentlemen of Verona: “Our day of marriage shall be yours, One feast, one house, one mutual happiness.”

Tragedy is about the breaking of those bonds, about decay, dissolution, isolation, and death—the death that comes too late. Tragedy is about being the The Last Man on Earth.

The Last Man on Earth can only be a “comedy” of union, of reunion, with the mother’s dead body. Mother Earth is destroyed, rival siblings are destroyed, the obstruction of the father is destroyed—all the obstacles of reality are destroyed, and the ancient wish is fulfilled: The Last Man on Earth has his mother to himself.

But the destruction of reality is psychosis, plain and simple—just as Norman Bates in Psycho destroys all other people he encounters, in order to have, and to be, his own dead mother.

*

Being The Last Man on Earth is a suicide mission. It is only attractive to the sick soul who, failed by his father, has had to destroy himself in an attempt to become a super-father, to be the first man—the poor soul who thinks that he is God the Father and the Son of God, and that his blood can save us.

It won’t. He can’t. He is sick. We are not sick. And even if we are sick, we don’t want to save or to be saved. We want to kill.

These are the facts of the case, and they are undisputed.

J. D. Daniels is the 2013 recipient of The Paris Review’s Terry Southern Prize. He will contribute an essay on group dynamics to the Spring 2015 issue of The Paris Review.

“A Noisy Cavalcade of Fraud,” and Other News

“Ingenious mendacity” ... How much do you have?

A reminder from literature: capitalism was always a disaster, even in the days when virtue and commerce were thought to go hand in hand. “The gentlemanly capitalism we were brought up to believe in was, if not wholly mythical, a sideshow in a noisy cavalcade of fraud, theft, and what Walter Bagehot called ‘ingenious mendacity’ on all sides … we should return to the pages of Dickens and Trollope to remind ourselves that there were wrong ’uns at every level and turn of nineteenth-century commerce, from crooked agents, clerks, brokers, and jobbers to ‘lords on the take, knights on the make’—and that ‘the thieves were often difficult to distinguish from the legitimate,’ to the cost of the ill-informed and gullible investor and customer.”

In Donetsk, Ukraine, as artillery continues to barrage the city, the show must go on. “The persistent shelling was barely audible through the thick stone walls of the Donetsk National Academic Opera … The highly regarded opera continues a regular schedule of weekend performances, as does the neighboring dramatic theater. Performers at the popular Donetsk circus, having finished their New Year’s routines, are planning a new round of shows in February. The planetarium open every weekend. Many cinemas are operating.”

Akhil Sharma on Chekhov the journalist: “Sakhalin Island is the greatest work of journalism from the nineteenth century … it has the pleasure of moving through a physical, distinct world and the keenness of documentary analysis.”

Van Gogh, method actor: He began his professional life “in the Borinage, the former industrial and mining region to the southwest of Mons … He originally intended to be a pastor, but the sickly, impoverished mining communities were often baffled by his attempts at asceticism and his clumsy efforts to fit in by wearing rags, blackening his face and sleeping on the ground.”

“Many of us have at least one thing we have put our name to that we have later regretted and desperately hoped might never again resurface to embarrass us, something that is far from guaranteed in an age of social-media outrage cycles … Pat Conroy’s novel The Great Santini was such a thinly-veiled portrayal of his tyrannical military father that Conroy’s mother presented it to the judge at her divorce proceedings, saying, ‘everything you need is in there.’”

February 4, 2015

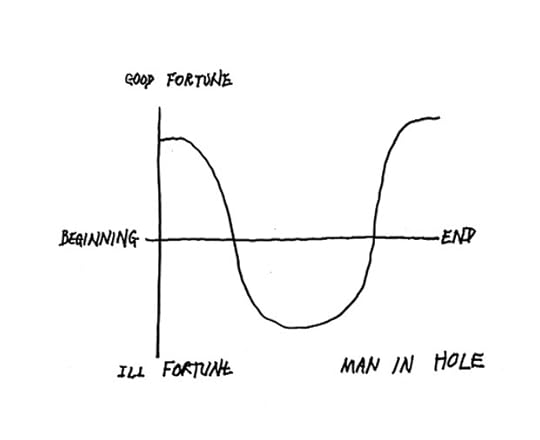

Man in Hole

Turning novels’ plots into data points.

Kurt Vonnegut

Motherboard has a new article about Matthew Jockers, a University of Nebraska English professor who’s been studying what he calls “the relationship between sentiment and plot shape in fiction.” Jockers has crunched hard data from thousands of novels in the hope of answering two key questions: Are there any archetypal plot shapes? And if so, how many?

The answers, his data suggest, are “yes” and “about six,” respectively.

Jockers, it should be clear, is pursuing a different meaning of plot than the one we conventionally reach for—he conceives of it as an emotional concern more than a narrative concern. His research was spurred by a concept called syuzhet, one of a pair of terms coined by the Russian formalist Vladimir Propp. As Jockers explains,

Syuzhet is concerned with the linear progression of narrative from beginning (first page) to the end (last page), whereas fabula is concerned with the specific events of a story, events which may or may not be related in chronological order … When we study the syuzhet, we are not so much concerned with the order of the fictional events but specifically interested in the manner in which the author presents those events to readers.

In other words, a book’s plot isn’t necessarily about conflict and resolution, but emotions, which “serve as proxies for the narrative movement,” as Jockers writes. This is an attractive approach to plot, in part because it allows us to ascertain—and to defend, if need be—the “plottiness” of certain books that tend to be regarded as plotless. It’s become conventional wisdom that plot, and the active enjoyment of it, are middlebrow pursuits, and that true literature is free from the shapely confines of narrative. This ignores that intricate, careful plotting is itself an art form, and that what makes so much “literary” fiction so ungodly boring is its inept or absent plotting. But by Jockers’s conception, even Waiting for Godot, which Vivian Mercier famously and favorably described as “a play in which nothing happens, twice,” is positively brimming with plot: chase sequences, surround-sound explosions, incestuous love triangles.

So how does Jockers get at the syuzhet, the emotional silhouette of a book’s body? He hasn’t revealed all of his methodology yet, but in essence, he’s using sentiment analysis, looking at the mood and tone of writers’ words—specifically “a controlled vocabulary of positive and negative sentiment markers … and a machine model that I trained to identify and score passages as positive or negative.”

I found this objectionable at first—the idea that something as complex as plot could be reduced, or even partially reduced, to a list of words with emotional valences. But there are only so many words, really, and though it may seem to flatten the whole transfigured human experience, most words have a fairly straightforward sentimental value. Here’s a random segment of the list of negative words Jockers drew from, for instance:

pout

poverty

powerless

prate

pratfall

prattle

precarious

precariously

precipitate

precipitous

predatory

predicament

prejudge

prejudice

And the positive ones:

gallantly

galore

geekier

geeky

gem

gems

generosity

generous

generously

genial

genius

gentle

gentlest

genuine

Jockers was inspired, too, by Kurt Vonnegut, who said in his rejected master’s thesis in anthropology for the University of Chicago, “There’s no reason why the simple shapes of stories can’t be fed into computers.” There are probably still writers who find that statement provocative. I don’t. It should be obvious to all writers that parts of “the craft” are deeply schematic; if you feel threatened by a machine, there’s probably something suspect about your humanism. We should resist the precious notion that there’s something inimitable about the whole enterprise of storytelling. Vonnegut definitely did: he found that stories tended to have eight shapes, including a kind of U-shaped one he called “Man in Hole” in which “somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again.” He also readily admitted that Hamlet’s shape was more or less a flat line—and that it was brilliant nonetheless.

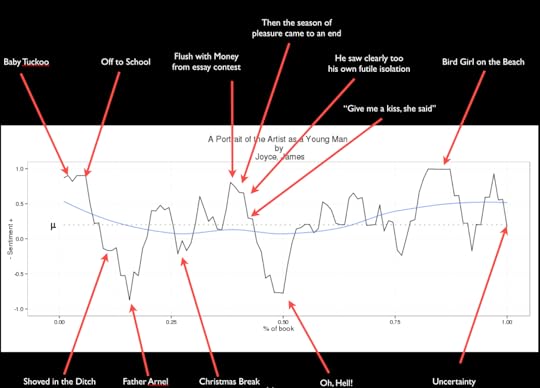

Jockers’s research has led him to a smaller number, six, and though he hasn’t told us what those six are, you can see already that he’s onto something. Here’s a chart tracking the shifts in emotional valence of Joyce’s Portait of the Artist:

Matthew Jockers

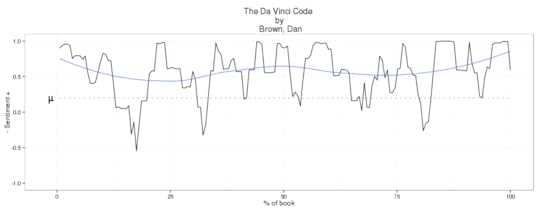

And here’s The Da Vinci Code:

Matthew Jockers

“Notice how much more regular the fluctuations are. This is the profile of a page turner,” he writes. “Dan Brown never lets the plot become too troubled or too much of a downer. He baits us and teases us with fluctuating emotion.”

I worked briefly for a film and theater producer who liked to speak of “pushing plot through” a script, as if plot were a waste product excreted through the screenplay’s GI tract. That makes the process, and the producer, sound crass and uncultured, but it was just the opposite: I can think of hardly anyone (certainly not most writers) who had such a sophisticated understanding of plot, who could see a story beat by beat. If yours wanted for drama, if its characters sometimes lacked motivation or some aspect of its narrative felt contrived, he could fix it, and not by cheapening or sensationalizing the plot, but by showing you, on your own terms, what the stakes really were. Tellingly, he eschewed the term “plot arc,” which summons a tidy rainbow of conflict and resolution, in favor of that uglier but truer “pushing plot through”: what a compelling story needs isn’t a clean trajectory but a healthy appetite and a good digestion.

As a reader and a writer, I’ve never found it easy to discuss plot; my alliances have never been clear. I have a deep admiration for writers like John Le Carré and Richard Price, who work unashamedly in genre fiction but whose novels, in part because of their convincing, complicated plots, are elevated to literature; I also like writers whose fiction seems to verge on total plotlessness (Nicholson Baker, Renata Adler), and writers who self-consciously mock the very struts and joists of plot (Donald Barthelme, Mark Leyner). And these knee-jerk reactions are complicated by research like Jockers’s, which suggests that plot is at once more subtle and more obvious than we’d expect—less a product of preconceived conflict and more indebted to a writer’s style and characters. Never has the question “What happens in it?” been more vexed.

It’s easy to mock what have emerged as the digital humanities, because they seem to partake of a lust for data, of data for data’s sake, that feels at the moment like an unseemly trend. But anyone who asks what use these charts could possibly have, what “practical value,” has already fallen into the trap that students of the humanities are supposed to avoid. Jockers (and others like Ben Schmidt, who has a fascinating analysis of the structures underlying thousands of TV and movie scripts) have already gotten us to ask questions about the foundations of plot—about what a plot is, even. I’ve come out of his work feeling that I know even less than I knew before: the mechanisms of storytelling are more ambiguous than ever. That in itself gives his work value.

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

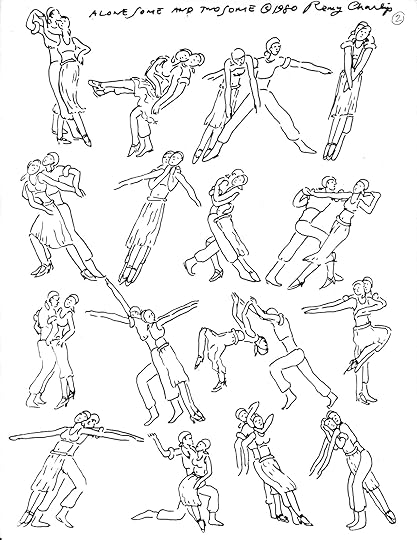

How to Write a Dance

Remy Charlip and the problems of dance notation.

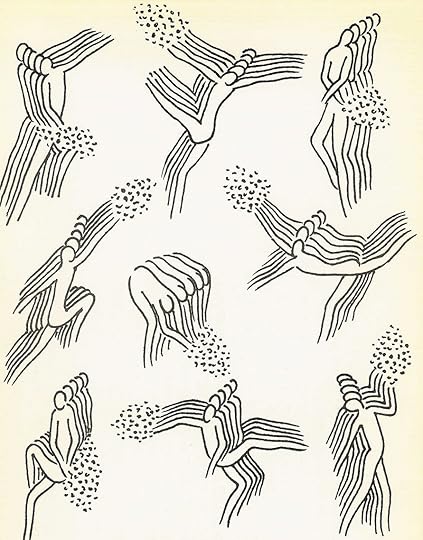

“Flowering Trees,” a page from Remy Charlip’s Air Mail Dances.

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

—W. B. Yeats

How do you tell a person in another place or time what a dance looks like, and how it should be performed? You could use words, describing, second by second, the movements made by every dancer on stage—but inaccuracies would creep in. Take an instruction as simple as “lower your arm”: How would the precise angle, attitude, and displacement of the arm be explained? As an algebraic vector? And what about the hand, the fingers, the knuckles, the rest of the dancer’s body—what are they doing? Such a method would come to resemble programming code, in which reams of language and symbols come to stand for something that’s supposed to look simple and elegant. The problem is that a dance is read by a human, not a machine.

What about images, then? You could reduce the dance to two dimensions, represented frame by frame, using diagrams and drawings. Yet even for a short sequence, you’d need so many! It would come to resemble a flip-book or an animated GIF, preempting the most efficient and simple method we’ve ever had to record dance: moving images, or film.

Before we had image-capturing technology, the need to preserve dance, as a record, gave way to attempts to write dance down. Dance notation, the symbolic representation of human movement, has developed into systems for making graphics recognizable as living movement. Traditional dance notation marks a path through space and a relationship to music. As Edward Tufte writes in Envisioning Information (1990), “Systems of dance notation translate human movements into signs transcribed onto flatland, permanently preserving the visual instant.” It’s a question of “how to reduce the magnificent four-dimensional reality of time and three-space into little marks on paper flatlands.” Dance never looks the same twice, unless it’s on film.

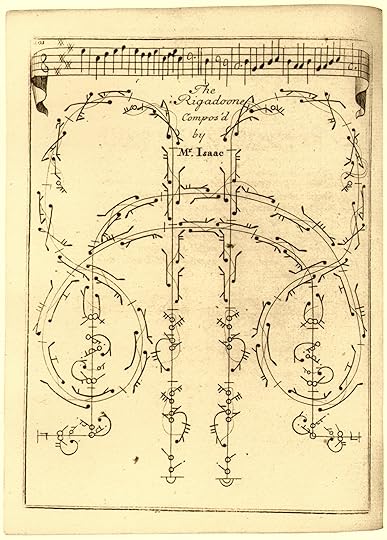

In the seventeenth century, around the same time he built Versailles, Louis XIV commissioned a method that became the Beauchamp-Feuillet system, made for Baroque dance, “La Belle Danse,” popular in the court. With Baroque, dance became a discipline, not just a pastime, in the Western world. Beauchamp-Feuillet was meant to teach courtiers the steps to the latest dance, but the result was that the style spread far beyond the court. (It was Raoul-Auger Feuillet who first notated the basis of ballet movement, the five positions of the feet.)

With Beauchamp-Feuillet, Baroque became a form of dance that, more than almost any other, exists in relation to its own notation. It alphabetizes the body, using it as a system of grammar. Beauchamp-Feuillet, unlike many previous forms of notation, envisions and uses the space in which the dance takes place—a square or rectangular room—as a page on which the body moves like a hieroglyph, making the writing.

A page of Beauchamp-Feuillet notation, circa 1721. In this case, a male dancer on the left and a female on the right begin upstage, facing downstage. In the first moments of this dance, the couple starts with feet at different angles, with the heel of the back foot touching the floor. Time value is indicated by lines that cross over the central line of direction. Beauchamp-Feuillet was useful mostly for representing a series of movements that were already recognized and encoded. It was difficult to indicate precise arm movements.

Remy Charlip, who died in 2012, was a founding member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, and an author and illustrator; a vital presence in New York from the fifties on, he worked with John Cage, Frank O’Hara, Edward Albee, and Robert Rauschenberg. A master of irreverence, and of sidestepping expectation, he taught a course at Sarah Lawrence from 1967 to ’71 in “making things up” and for two years directed the National Theatre for the Deaf.

Like Baroque dance in the court of Versailles, Charlip’s Air Mail Dances depend on notation for performance—they originated from drawings on cards. Charlip began to make these dances in 1971, having promised to choreograph a dance for his friend Nancy Lewis and then forgotten about it. When he was reminded, with a fortnight to go until the performance, he drew the rough positions on postcards: figures in different poses, demonstrating the landmarks for the dancer to pass through. The transitions between drawings he left up to the performer.

“I did a whole set of positions, of movements, signs,” he said in an interview. “I gave her gestures that I thought were very beautiful and between the gestures I said do a turn. And I left it up to her … It’s their dance, and it’s also my dance.” His figures are sometimes annotated—some with clear instructions, like “roll slowly,” others with more abstract suggestions, like “crackle.” Charlip’s drawings are rough, beautiful, and endearing, a reminder of how much the choreographer relies on the dancer to realize a work.

Charlip liked to play with the way we conceive of dance movements. On a recent Friday at the 92nd Street Y, a program put together by Catherine Tharin called “Remy Charlip: I Love You” restaged a number of his works. In his series “Imaginary Dances,” performed at the Y by David Vaughan, choreographic instructions for would-be performances are read aloud with a cheeky apology that, due to lack of funding, they can’t be performed. In “Waiting Dance,” we hear: “Curtain rises. Any number of people on stage, all waiting, for as long as they want to. Curtain closes.” And in “Sardines”: “Eight boys and girls undress and get into a bathtub. They arrange themselves comfortably. The choreographer pours warm olive oil over them. Curtain.”

Some, like “Storm,” are fantastical:

A special well-drained waterproof room is constructed, where over the audience’s heads, a glorious sunset is enacted, cross fading into a full moon rising among stars. Clouds arrive, become denser, and turn everything into darkness. Thunder, lightning, then droplets of rain slowly build up to a shower, then a storm. Hurricane, tornado and flood may be added if budget is big enough.

Charlip’s performances show us how images in the head of a choreographer become the movement of another person. His system of notation—irreverent, idiosyncratic, imprecise—makes visible the process of idea to movement. “The language of dance,” he said once,

is basically physical … there are lots of ways language can be used to convey the physicality of it, and the images and thoughts that are used in dancing … you can get behind a person and you can move them, or you can be in front and have them imitate you. Or you can give them an image … so that they can move from the images.

Among the Air Mail Dances is “Dance in a Bed,” two pages of images, showing movement that takes place in (yes) a bed. The Y showed a film of its first performance, by the dancer Toby Armour: slow and languid, she wears backless silk pajamas and is accompanied by Saint-Saëns’s Le Cygne. But the piece has also been performed by Sally Hess to quick and restless Shostakovich music, and called Nuit Blanche, for a sleepless night. The same choreography inspires two different performances: one for those of us who jump quickly out of bed, and one for those who press the snooze button.

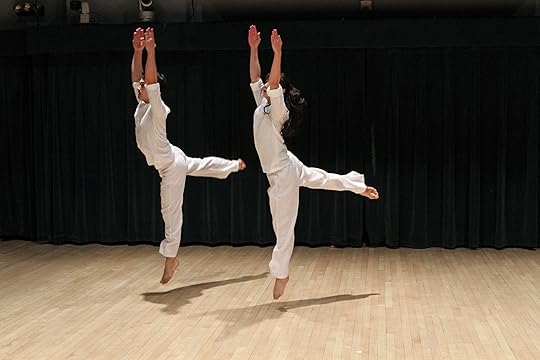

“Remy Charlip: I Love You” at the 92nd Street Y. Photo: Julie Lemberger

“Remy Charlip: I Love You” at the 92nd Street Y. Photo: Julie Lemberger

Today dance notation is arcane, and mostly inessential to the art of dance. Even the two most prevalent systems, Laban and Benesh, don’t enjoy wide literacy among dancers. Lincoln Kirstein, of the New York City Ballet, wrote in his Ballet Alphabet,

A desire to avoid oblivion is the natural possession of any artist. It is intensified in the dancer, who is far more under the threat of time than others. The invention of systems to preserve dance-steps have, since the early eighteenth century, shared a startling similarity. All these books contain interesting prefatory remarks on the structure of dancing. The graphs presented vary in fullness from the mere bird’s-eye scratch-track of Feuillet, to the more musical and inclusive stenochoreography of Saint-Léon and Stepanov, but all are logically conceived and invitingly rendered, each equipped with provocative diagrams calculated to fascinate the speculative processes of a chess champion. And from a practical point of view, for work in determining the essential nature of old dances with any objective authority, they are all equally worthless. The systems, each of which may hold some slight improvement over its predecessor, are so difficult to decipher, even to initial mastery of their alphabet, that when students approach the problem of putting the letters together, or finally fitting the phrases to music, they feel triumphant if they can decipher even a single short solo enchaînement. An analysis of style is not attempted, and the problem of combining solo variations with a corps de ballet to provide a chart of an entire ballet movement reduces the complexity of the problem to the apoplectic.

In other words, the very idea of trying to hurry along in the wake of a dance and record its movements is inelegant. But Charlip’s dances show us the fluidity between the dancer and the scribe: they allow us to think of notation as a way to invent movement, rather than just try to preserve and petrify it. One of the chief features of his drawings is their accessibility—they’re like invitations to the audience to join in.

On a radio show, Charlip once spoke about a book he wanted to make, a kind of do-it-yourself instructional manual of Air Mail Dances:

It would be called Dances Any Body Can Do. And they would be mostly household dances, like, dance in a doorway, dance on the stairs, dance in a bed, and other dances that you can do that would be very simple. And I’d like to do a second book called Advanced Dances, and those would require more technical proficiency. And then I’d like to do a third book, and those would be called More Advanced Dances, which would be very difficult to do, like dancing on the tip of a candle flame, or dancing on a cloud …

And here, the recording trails off.

Anna Heyward is a writer and reporter in New York.

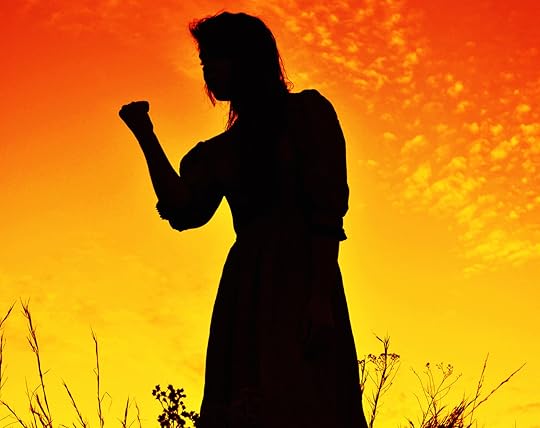

As God Is My Witness

“As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again!” —Gone with the Wind

The clue for 2 Down on today’s New York Times crossword is as follows: “ ‘If you ask me,’ in textspeak.” Spoiler alert: the answer is IMHO. (Short for “in my humble opinion” or “in my honest opinion,” for those who didn’t know.) This is true not merely because you need those letters to satisfy the needs of mire and Amex and Sofia but because in the world of texts, and in online communication generally, people are constantly asserting their opinions with unnecessary vehemence.

Leaving aside the fact that such opinions are rarely solicited, why is everyone always sharing his “honest” or “humble” opinion? As opposed to what—the civility that normally characterizes anonymous online discussions? Because otherwise we might think you were prevaricating about, like, whether you thought some dumpling shop was overrated or one season of a show was better than another? IMHO asserts that someone is about to tell you the truth—but your veracity otherwise would never have come into question.

Speaking of vehemence of this sort, I recently ran across a very impassioned post on Chowhound. Here is what the poster said:

The lamb was served magnificently, not just falling off the bone but fully fallen off it. Some bone, somewhere—but, as God is my witness, that meat had not fallen off that bone. The meat was artfully arranged along the bone, and, naturally, I tried to reconstruct the shank. The cubes of meat did not fit the curvature of the bone. Plus, the meat was piping hot and the bone just warm.

Now, this is a case where such rhetoric (“God is my witness”!) is appropriate, or necessary, even. It should electrify. It should stand for something. On dinner plates, in New York politics, and, especially, in textspeak.

Reading’s Journey from Chore to Passion, and Other News

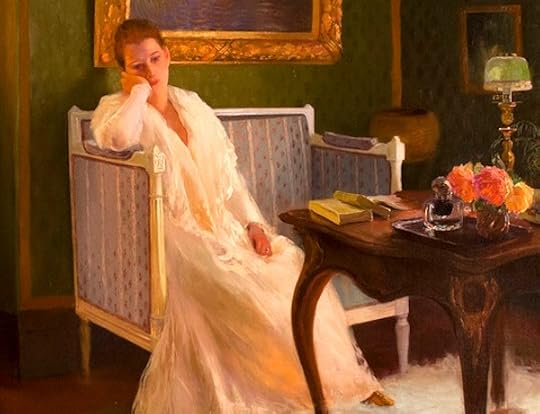

Gaston de la Touche, L’ennui, 1893.

We begin with the decline and fall of the English major: Have our nation’s youth really found something better to do? “If our spring 2015 numbers follow the pattern of our recent death spiral,” one professor said, “we will have lost in four years twice as many majors as we gained in fifteen.” Another theorized that “many students who would prefer to declare humanities majors might be challenged or advised to declare a ‘practical major.’ ”

But even those of us who threw caution to the wind and majored in English have not done such a hot job of pursuing literature in other languages. “About 3 percent of all the books published in the U.S. every year are translations. But the bulk of these are technical writings or reprints of literary classics; only 0.7 percent are first-time translations of fiction and poetry.”

Still, shouldn’t we congratulate ourselves for living in an era when reading is regarded as a joy, a passion, rather than as a necessary, bland consequence of rhetorical culture? “For a long time, people didn’t love literature. They read with their heads, not their hearts (or at least they thought they did), and they were unnerved by the idea of readers becoming emotionally attached to books and writers. It was only over time—over the century roughly between 1750 and 1850—that reading became a ‘private and passional’ activity, as opposed to a ‘rational, civic-minded’ one.”

Today, by contrast, we’re so in love with literature that one can earn seven hundred dollars a week simply by writing poems on the subway. And they don’t have to be good poems, either. (“Faint sweeps / Of sea breeze / In the light stream of / Water … ”)

Most of us prefer to write in private—others of us have no choice. Anna Lyndsey has a rare illness that makes her skin burn whenever she’s exposed to light, even the light of an iPhone. She lives in darkness. She gets her news from the radio. She writes. “She found that, with practice, she could write in her head—marshal thoughts into sentences, arrange sentences into paragraphs—before writing longhand in a notebook. It was liberating, not being able to see her words on the page. Darkness, it seems, is also a cure for self-consciousness.”

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers