The Paris Review's Blog, page 618

February 10, 2015

A Beautiful Friendship

In a nod to the recent Grammy Awards, allow me to pay tribute to a record that was nominated in 1963, in the category of Best Documentary or Spoken Word Recording (Other than Comedy). That record is Enoch Arden, Op. 38, TrV. 181, performed by Glenn Gould and Claude Rains.

Most people probably know Claude Rains best as the blithely unscrupulous Captain Renault in Casablanca, or maybe as the gleefully unscrupulous Prince John in The Adventures of Robin Hood, or even as a wholly unscrupulous senator in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. No question, Rains brought particular élan to a certain kind of villain—yet nowhere did he commit as fully to a performance as to Enoch Arden.

Enoch Arden was written explicitly for narrator and piano; it’s a setting by Richard Strauss of Tennyson’s narrative poem. Tennyson wrote “Enoch Arden,” a sort of Odysseus story, in 1864, while he was England’s poet laureate. The eponymous hero is shipwrecked on a desert island for ten years, and given up for dead; when he returns home, it’s to find his wife happily remarried to his best friend, and one of his children dead. Enoch Arden cannot bear to destroy their lives, and so keeps his identity a secret and dies of a broken heart.

Needless to say, the resulting musical adaptation is dramatic. While it’s not generally considered one of Strauss’s most distinguished works, it was a hit at the time of its writing, when such musical melodramas were enjoying a vogue. Indeed, the entire piece is a dizzy immersion in Victoriana.

Which is part of what makes the Rains-Gould recording so wonderful. Both artists are unmistakably themselves: you never forget for one moment that you're listening to Rains’s plummy voice or Gould's emphatic phrasing, yet the whole thing is incredibly old-fashioned. And there’s not an iota of irony about it; both are fully committed. What I’m trying to say is that the 1963 Glenn Gould–Claude Rains recording of Strauss’s Enoch Arden is both a triumph of high camp and a genuinely moving, passionate performance by two great artists, and I insist you listen to it this instant.

No one was under the illusion this would appeal to the general public. Only two thousand copies were pressed. And yet, there have been many subsequent versions of the piece: most recently, by Patrick Stewart and Emanuel Ax in 2007. As for the 1936 Grammys, Enoch Arden lost out to The Story-Teller: A Session With Charles Laughton. And given that the latter includes superlative readings of Shaw, Plato, and Margaret O’Brien, it’s hard to feel as though the forces of philistinism won out.

Sadie Stein is contributing editor of The Paris Review, and the Daily’s correspondent.

One Wine, Two Wine, Red Wine, Blue Wine

Naming wines in translation.

Georg Emanuel Opitz, Der Säufer, 1804.

Valentine’s Day is upon us and if, to bedazzle your beau or belle, your tastes turn to thoughts of white tablecloths and candlelight, your thoughts will likely turn to tastes of wine.

But which wine? It can be hard to navigate those artisanal descriptions, so easy to mock—notes of saddle leather, jujubes, and turpentine with a hint of combed cotton, and so on. The basic questions are no simpler, though. “Red or white?” ignores orange wine, whites tinted a little longer than usual from the grape skins: basically the opposite of rosé, where red-wine grapes are peeled faster than usual. There’s also gray wine (vin gris, actually pinkish), which is white wine from black grapes usually used for red wine such as pinot noir, and even yellow wine (vin jaune), a special variety from the Jura in eastern France, though what white wine isn’t yellow when you think about it. Provençal pink wines—rosés—are colored gooseberry, peach, grapefruit, cantaloupe, mango, or mandarin, according to the Provence Wine Council: vote for your favorite here.

Vin jaune: the author’s Valentine’s Day plans.

What are these colors anyway? “Red” wine isn’t actually red, like fire engines or stop signs, any more than “white” is white like snow or those tablecloths. And we don’t have “white grapes” in English, though we do have red: we have green grapes (and yellow raisins), and black, purple, and blue grapes, too. Color perception, and color words, are vast and fascinating topics, best plumbed in the magnificent, luxurious, inexhaustible Color and Culture by John Gage, from which I take much of what follows. Different cultures have different color schemes, and as the centuries go by, especially if paintings and fabrics fade or are lost, it can be hard to know what people meant by a given word.

Purple, as in the Roman “royal purple” whose misusers could face the death penalty, probably meant a luster or shimmeriness, not a hue. There are color-fast artworks, like mosaics, that show garments known to be purple, but which we would now call vermillion-red, green, or black, with shimmers of light. In Medieval Spain, the word for purple meant a thick fabric, probably silk, of almost any color; the Anglo-Saxon translation of purpura was godweb: a good, or godly, weave.

Then there’s perse: no one knows what the hell that means. In the eighth century, it was a synonym for hyacinth; in Dante, it’s purple-black; at its heyday, it was the darkest and most expensive blue; its last appearance, in the mid-sixteenth century, was as the color of rust. It, too, might be more like a kind of material or some non-hue color value.

The most well-known color-translation problem is Homer’s “wine-dark sea”—the sea rarely being, of course, what we would call the color of wine of any color. Explanations relying on poetic license or metaphors of intoxicating depths quickly run aground on the rest of Homer’s color terms: He calls oxen “wine-dark,” too. The sea, when not “wine-dark,” is “violet,” an adjective he also applies to sheep. Honey is “green.” There are five words for hues in all of Homer’s work, including words for fiery-red and purple-red, but none for blue—despite living under the most splendid, perfect blue in the world, Homer calls his sky starry, or broad, or great, or iron, or copper, or bronze, but never once blue.* Kuaneos, which in later Greek meant blue, is used only for a storm cloud, Hector’s hair, Zeus’s eyebrows: “dark.” Maybe he had no choice but to call the sea wine-colored.

So about that “red” wine, maybe it’s best to stick to the winemaker’s name on the bottle? That presents other problems, in some languages. English speakers take for granted our ability to just borrow some French if we need it, for Burgundy, champagne, Château Lafite-Rothschild. We have the same alphabet as French, give or take a few accents, and more or less know how to pronounce the unfamiliar thing if we see it. Even words from non-Western languages are usually easy to transliterate: Honda, Al Jazeera.

Not so in Chinese. And with high-end wine exports from France hitting record numbers this decade because of Asian demand—French wine took in ten billion euros in 2011, beating the previous record by more than 10 percent, and 2.5 billion was from Asia—what the Chinese consumer sees as a wine’s name has started to make a big difference.

The challenge of translation between Chinese and European languages never ceases to amuse, for which see any number of so-called Chinglish Web sites illustrating signs or instructions gone terribly wrong. Translations of proper nouns into Chinese pose even more problems, because a French or English syllable can be matched by a dozen or more different Chinese words, each with a different meaning. As a result, even straight transliteration runs into semantic cross fire: not only must the name be easily pronounced and appealing in Chinese, and sound roughly the same as the original, but unlike a transliteration into English it will mean something, too, one hopes something positive or brand-appropriate. It was a bummer for Microsoft that “Bing” is most naturally heard in Chinese as 病, meaning “illness” or “being sick.” Good save, though: they called their search engine bi-ying (必应), “must answer.”

The two companies you hear about who aced the challenge are Subway, which in Chinese is sai-bai-wei (赛百味), “better than a hundred flavors,” and the brilliant keh-kou keh-luh (可口可乐), which sounds like “Coca-Cola” and means “delicious happiness” or “good to drink, makes you happy.” I like Groupon’s name: gao-peng (高朋), “classy friends”; I’d probably like Groupon more if it were called Classy Friends in English, too.

What about wine? As you’d expect, total chaos. Some names could be translated (Château La Lagune as lang-lihu, “beautiful lake”), some wines simply renamed: Château Beychevelle became the auspicious longchuan (“dragon boat”), playing off the Viking ship on its label. Calon-Ségur lucked out with tianlong (sounds like “Calon,” means “dragon of heaven”); Lafite hit the jackpot with the blingy lai-fat, “Come get rich!” and became the lubricant of choice for negotiating big-money Chinese business deals. Grand Puy Lacoste got saddled with “crocodile wine,” because of the crocodile logo of Izod Lacoste, no relation. Crocodiles being neither auspicious nor tasty, sales sagged.

There have been two attempts I know of to nail this all down, in the interests of making everything easier to sell. In 2009, the publisher of Singapore’s The Wine Review and founder of the bilingual Chinese Bordeaux Guide offered phonetic translations of the top Bordeaux châteaux names; in 2012, after a year of consultation with the sixty-one châteaux in Bordeaux’s official 1855 Grand Cru classification, of “official translations” and said that all but four châteaux had approved it. They also announced the first-ever Chinese wine-tasting notes, a whole other crosscultural kettle of crocodiles. They prepared a poster to be “given to Christie’s clients and journalists,” but the project seems to have quietly disappeared—as far as I know, the poster never came out, although a low-res version is used to illustrate .

I talked to Simon Tam, the Head of Wine, China, at Christie’s, when the plans were still moving ahead, and asked him about their translations. He wouldn’t say much about the process—was the project managed in English, Chinese, or French, for instance—but he did say that Christie’s had decided to come up with the list on their own initiative. Tam felt that “the time had come for an authority to set some standards,” and clearly Christie’s wanted to be identified with these high-quality standards. No more flat translations of Cheval Blanc as “white horse”—they looked for “characters that are elegant, less day-to-day, words that look good together.” (Still, Cheval Blanc did great at last year’s Sotheby’s auction marketed as a celebration of the Year of the Horse, and China-savvy diplomats have already stocked up on Réserve de la Chèvre Noire, Le Bouc à trois pattes, and La Ferme Julien—goats black, three-legged, and on the bottle’s label, respectively—for next week’s Year of the Goat New Year’s gifts.)

Tam approached the châteaux and asked if they were happy with their Chinese name, and if they weren’t, he and his team offered suggestions. Their goals were “accuracy and identity,” what Tam called the château’s “brand DNA”: for instance, masculine or feminine.

Fine French wines and the booming Chinese market were “the newest combination on the block,” and “all we’ve done,” Tam said, was “fast-track it for the industry.” Here’s to fast-tracking new combinations, and maybe even some new colors, this Valentine’s Day.

*Near-quoted from William E. Gladstone, who called attention to the issue in his three-volume Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age before becoming one of the greatest British prime ministers in history: “Homer had before him the most perfect example of blue. Yet he never once so describes the sky. His sky is starry, or broad, or great, or iron, or copper; but it is never blue.” The “bronze” sky is mentioned in Gage.

Damion Searls, the Daily’s language columnist, is a translator from German, French, Norwegian, and Dutch.

Read, Reread, Re-reread, Re-re-reread, and Other News

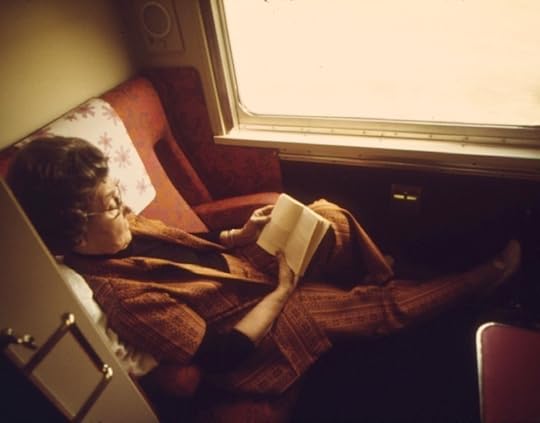

A passenger reading on a train to Houston, 1974. Photo: NARA

It’s one thing to be well read—quite another to be well reread. Stephen Marche has coined the term centireading, i.e., reading something a hundred times. He’s accomplished only two feats of centireading (Hamlet and The Inimitable Jeeves), but they effectively restored the purity of his reading experience: “The main effect of reading Hamlet a 100 times was, counter-intuitively, that it lost its sense of cliché. ‘To be or not to be’ is the Stairway to Heaven of theatre; it settles over the crowd like a slightly funky blanket knitted by a favorite aunt. Eventually, if you read Hamlet often enough, every soliloquy takes on that same familiarity. And so ‘To be or not to be’ resumes its natural place in the play, as just another speech. Which renders its power and its beauty of a piece with the rest of the work.”

As a moneymaking device, the book is obsolete, as we all know. Of course it is—it’s very, very old. What you might not have heard yet is that Web sites are obsolete, too, and that your mere presence on this page renders you a technological dinosaur. It’s okay. I’m one, too. This man is not: “In his weird zone of the internet, he said, the concept of a large publication seemed utterly hopeless. The only thing that keeps people coming back to apps in great enough numbers over time to make real money is the presence of other people. So the only apps that people use in the way publications want their readers to behave—with growing loyalty that can be turned into money—are communications services. The near-future internet puts the publishing and communications industries in competition with each other for the same confused advertising dollars, and it’s not even close.”

From the makers of the flaneur, meet the crónica: “a crónica is both ‘a history that obeys the order of the times’ and ‘a journalistic piece … about current events.’ But it is more. Starting in the nineteenth century, crónica and urban life became inseparable; to the mere recording of a city life for posterity, the genre added flânerie and modern investigative reporting. Together, crónica and la ciudad (the city) inform a typology of ‘essaying’ a pie (on foot), in which walking is to thinking what seeing is to reading, and cities’ ‘intensification of nervous stimulation’ becomes social and cultural criticism.”

In France, even illicit, politically scandalous affairs play out like fairy tales: “It was not until his press attaché phoned Valérie and informed her that François was ‘madly in love with you’ that Valérie recognized the current of passion that roiled beneath their professional rapport … They were committed to others—Ségolène and Denis—and they had more than half a dozen children between them, but how could they refuse love’s call? Over crêpes and waffles, Valérie and François confessed their feelings, which led to, she wrote, ‘a kiss like no other kiss I’d ever shared with anyone. A kiss that had been held back for nearly fifteen years, in the middle of a crossroads.’”

William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One is one of the most daring movies of the sixties, which may be why no one saw it until 1991. Now his film is finally getting its due: “Greaves was up there with John Cassavetes and Shirley Clarke in the blend of sophisticated modernism and emotional fury, of self-implication and formal innovation, of self-revelation and revelation of the heart of the times.”

February 9, 2015

Certificate of Tastelessness

Thomas Bernhard in Portugal, 1986.

At this point, we tired of it! Because what happens is, when you keep on diminishing art and not respecting the craft and smacking people in the face after they deliver monumental feats of music, you’re disrespectful to inspiration … Then they do this whole promotional event, and they’ll run the music over somebody’s speech, an artist, because they want commercial advertising. No, we not playing with them no more. —Kanye West on the Grammys, February 8, 2015

Every year, the stately procession of awards shows delivers us another imbroglio, and every year I wish that Thomas Bernhard, who would be eighty-four today, was still around to take the piss out of them. In a just world, our country’s glossiest magazines would pay Bernhard to attend awards shows around the world, allotting him thousands of words with which to vent his signature blend of misanthropy, contumely, vitriol, and spleen, with no paragraph breaks. “Everything is fundamentally sick and sad,” Bernhard once wrote. And: “There is nothing but failure.” If the Kanye Wests of our time were stealing the stage to say stuff like that, the state of our union would be stronger.

Bernhard was full of vinegar for just about everyone and everything, but so severe was his allergy to pomp and circumstance that he wrote a book about it. My Prizes: An Accounting describes a variety of banal ceremonies Bernhard was swindled into attending because, you know, he was being feted at them. “The Grillparzer Prize,” which opens the collection, provides a useful blueprint for anyone who hopes to disrupt the prizewinning paradigm. Some general instructions follow.

Step One: Fly by the seat of your pants, and make sure those pants are only a few hours old. The start of “The Grillparzer Prize” finds Bernhard buying a suit on a whim off the rack at St. Anthony’s, one of the “so-called finer emporiums” where “even if the customer immediately says what he’s looking for in the most concise terms, at first he’ll be started at incredulously until he repeats what he wants … I myself knew better than the salesman where to find the suit I was looking for.”

He wears it out of the store—carrying his street clothes in a “deeply repellent” bag with the St. Anthony’s insignia on it—and soon discovers that it doesn’t fit.

Step Two: Attend the ceremony with your aunt. Why not? Bonus points if she’s a phlegmatic, affectless, eighty-one-year-old aunt whose catchphrase is “Well, all right.” “She was very happy about the fact that the Academy of Sciences was awarding me that Grillparzer Prize today, she said, and proud, but more happy than proud.”

Step Three: “Eat a sandwich to forestall any malaise or even fainting episode during the proceedings.”

Step Four: No matter what, act as if you’ve been snubbed the moment you arrive. Sit in the back of the room and refuse to take your assigned seat until the most important person in the house greets you, thus preventing the ceremony from starting on time.

Up in front on the podium at ever-decreasing intervals excited gentlemen were running this way and that as if they were looking for something, namely me. The running this way and that by the gentlemen on the podium went on for a while, during which unrest was already breaking out in the hall. In the meantime the Minister of Sciences had arrived and taken her seat in the front row … Suddenly I saw a gentleman on the podium whisper something into the ear of another gentleman while simultaneously pointing into the tenth or eleventh row with an outstretched hand, I was the only one who knew he was pointing at me. What happened next is as follows: The gentleman who had whispered something into the ear of the other gentleman and pointed at me went down into the hall and right to my row and made his way along to me. Yes, he said, why are you sitting here when you’re the most important person in this celebration and not up front in the first row where we, he actually said we, where we have reserved two places for you and your companion? Yes, why? … The President, said the gentleman, is asking you please to come to the front, so please come to the front, your seat is right next to the Minister, Herr Bernhard. Yes I said if it’s that simple, but naturally I will only go into the first row if President Hunger has requested me personally to do so, it goes without saying only if President Hunger is inviting me personally to do so … I saw that President Hunger was laboriously making his way toward me. Now is the time to stand firm, I thought, demonstrate my intransigence, courage, single-mindedness. I’m not going to go and meet them, I thought, just as (in the deepest sense of the word) they didn’t meet me.

Step Five: Judge everyone. “The minister was snoring, even if quietly, she was snoring the world-famous ministerial snore. My aunt was following the so-called ceremony with the greatest attention, when some turn of phrase in one of the speeches sounded too stupid or even too comical, she gave me a complicit glance.”

Step Six: When receiving your prize, regard it as an icon of hollowness, the apex of nihilism. “I stood up and went to Hunger. He shook my hand and gave me a so-called award certificate of tastelessness, like every other award certificate I have ever received, that was beyond comparison … I thought over the entire ceremony now ending, whose peculiarity and tastelessness and mindlessness naturally had not yet had the chance to register in my consciousness.”

Step Seven: Leave early when no one is looking. “After a time the minister looked around and asked in a voice in which inimitable arrogance competed with stupidity: So, where is the little poet? I had been standing right next to her but I didn’t dare to make myself known. I took my aunt and we left the hall.”

Step Eight: Return the suit. It doesn’t fit anyway. Nothing fits. “Whoever buys the suit I have just returned, I thought, has no idea that it’s been with me at the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna. It was an absurd thought, and at this absurd thought I took heart.”

Dan Piepenbring is the web editor of The Paris Review.

Hot Stove

A young Harper Lee, her thoughts no doubt consumed by the New York Mets.

Harper Lee fever has gripped the nation. Ever since news of her lost novel hit last week, the famously reclusive writer has been everywhere—trending on Twitter, spawning lists, smiling above the fold on the front page of today’s New York Times. Naturally, there’s been as much controversy as delight: Is the elderly author being taken advantage of? Does she want the book released? According to her lawyer, the author is humiliated by such allegations.

Whatever you think about the release of the novel, the whole thing has started to feel a bit squicky, or at the very least odd. All of this has so little to do with the woman herself. Or so I declared self-righteously to my head over the weekend, when I resolved to take an attitude of superior distaste towards the whole business. When I saw a feature on Harper Lee’s New York in the New York Post, my lip curled. Until, that is, I glanced at the annotated map and saw that it listed—along with the Yorkville flat where Lee lived off and on for decades, Capote’s Brooklyn Heights home, and the offices of agent Maurice Crain—the old Shea Stadium.

And that, of course, changed everything. As every fan of a punch line team knows, we cannot afford to ignore any fellow travelers in the cause. And Harper Lee: what a get! All of a sudden, I was totally ready to throw my scruples to the wind and use the eighty-eight-year-old’s long-ago devotion to the Mets for my own selfish ends. Or, you know, Mets ends. Since learning this, I have mentioned that Harper Lee was a Mets fan to no fewer than five people, with an air of smug triumph reserved for the truly irrational. “Harper Lee,” I said casually to a businessman reading the paper on the subway. “You know she was a big Mets fan, right?”

“You know who loved the Mets?” I demanded of a guy on the street in a Mr. Met–patterned knit hat. “Harper Lee.”

It would be hard to say which of them cared less.

In fairness, in a world of tenuous claims, this seems to be a relatively plausible one. Marja Mills, the author of The Mockingbird Next Door, termed Lee “a rabid Mets fan”; Andrew Haggerty described her as “passionately devoted” to the team. Meanwhile, Lee’s biographer Charles Shields told the Post, “She was a big Mets fan—she used to go around with a Mets hat on.” And Smithsonian magazine pointed out (rather gratuitously), that the team was “the natural choice for someone with an underdog thing as big as the Ritz.”

With all due respect to Julian Casablancas, Jon Stewart, and Anthony Weiner, Harper Lee is the best celebrity-face the Mets have had since the death of P. G. Wodehouse. She brings with her not merely gravitas and mystery, but all the moral authority of Atticus Finch. Clearly, the Mets are (as we always suspected, on sometimes tenuous evidence) the choice of the morally righteous.

You might say: It’s a very different team now. It’s a very different world. The Mets aren’t lovable underdogs anymore; they’re just another rich team who’s badly managed, whose stadium has the name of a huge bank. Harper Lee wearing a Mets cap in the sixties has nothing to do with the team today, and certainly has nothing to do with you. But you can’t really look at the world that way, certainly not in the preseason. You gotta believe.

Sadie Stein is contributing editor of The Paris Review and the Daily’s correspondent.

The 2015 Folio Prize Shortlist

This morning, the Folio Prize announced the eight novels on their 2015 shortlist. The prize, now in its second year, is the only major English-language book award open to writers around the world; it aims “to celebrate the best fiction of our time, regardless of form or genre.” Its chair of judges, William Fiennes, told the Guardian that the books on this year’s list “say something true about human experience in a way that feels like something new”: “There’s dazzle and wildness and experiment hand in hand with a deep core commitment to human struggles and fervors and longings.”

This morning, the Folio Prize announced the eight novels on their 2015 shortlist. The prize, now in its second year, is the only major English-language book award open to writers around the world; it aims “to celebrate the best fiction of our time, regardless of form or genre.” Its chair of judges, William Fiennes, told the Guardian that the books on this year’s list “say something true about human experience in a way that feels like something new”: “There’s dazzle and wildness and experiment hand in hand with a deep core commitment to human struggles and fervors and longings.”

Plenty of that dazzle and wildness is already familiar to our readers, who have encountered three of this year’s shortlisted novels in The Paris Review. Parts of Ben Lerner’s 10:04 appeared in our Summer 2013 and Spring 2014 issues; our Winter 2014 issue included an extract from Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation; and in that same issue, we began to serialize the entirety of Rachel Cusk’s Outline. We’re delighted that the three of them have been recognized for their work.

The full shortlist is below—congratulations to all the nominees. The winner will be announced on March 23.

10:04 by Ben Lerner

All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill

Dust by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

Family Life by Akhil Sharma

How to Be Both by Ali Smith

Nora Webster by Colm Tóibín

Outline by Rachel Cusk

Dreams from a Glass House: An Interview with Josiah McElheny

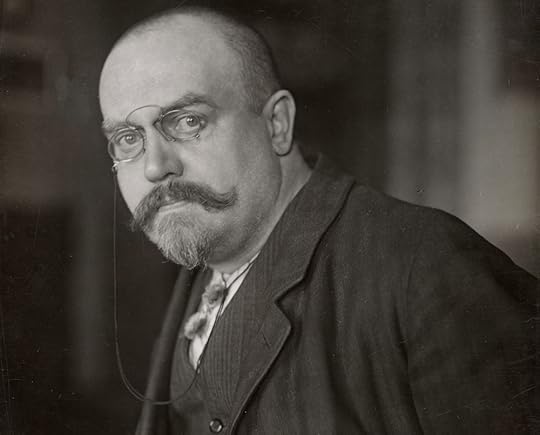

Phillip Kester’s portrait of Paul Scheerbart, 1910. Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Fotografie, Archiv Kester

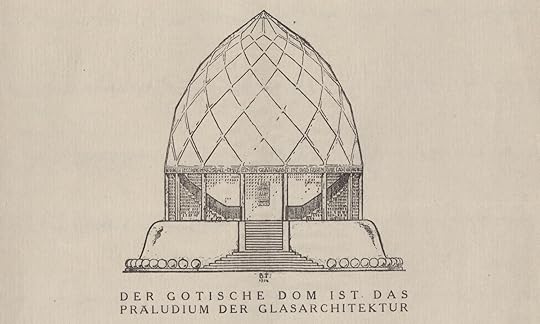

Paul Scheerbart doesn’t figure very prominently in modern German belles lettres—nor, more regrettably, on the drafting tables of venerated Berliner architects and urban planners. Scheerbart, an eccentric, Danzig-born poet and architectural theorist, is best remembered through obscure citations from Walter Benjamin, Walter Gropius, and Bruno Taut. But in the spirited era of Berlin’s café culture, he was a popular serialist, publisher, and proto-surrealist. From the late 1880s to his premature death in 1915, he wrote prolifically on science, urban planning and design, space travel, and gender politics, often in the course of a single text. His most celebrated treatise, Glass Architecture (Glasarchitektur, 1914) foretold of a sublime, technocratic civilization whose peaceful world-order was borne from the proliferation of crystal cities and floating continents of chromatic glass, a vision summed up in his aphorism: “Colored glass destroys all hatred at last.”

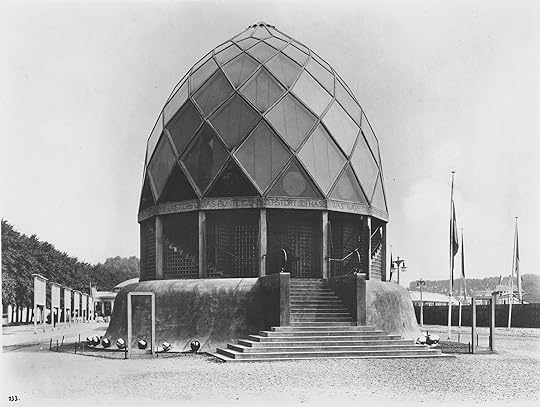

Taut, an architect and devoted disciple, dedicated his 1914 Werkbund Exhibition building, the Glass House, to Scheerbart—his so-called “Glass Papa.” Like his French contemporaries Camille Flammarion, Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, Raymond Roussel, and Alfred Jarry , Scheerbart’s prophetic oeuvre oscillated between themes of technology and aesthetics in a genre known in the Francophone world as fantastique.

Translations of Scheerbart texts have trickled into the English-speaking realm; Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!!: A Paul Scheerbart Reader , edited by Josiah McElheny and Christine Burgin, is the first attempt at an English-language collection. Assembled from his fiction and critical works, drawings and photographs, and secondary texts from friends and acolytes, the book’s publication hopes to inspire what McElheny calls a new generation of “Scheerbartians.”

I recently spoke to McElheny by phone from his studio in Brooklyn, where we discussed Scheerbart’s belated American reception, the cultural amnesia of World War I, and our mutual fascination with Utopian literature.

How did you first come across Scheerbart’s writing?

The first major publication of his work in translation was Glass Architecture in 1972. I read that sometime around 1988, and I didn’t really know what to make of it. I came to it as though it were an architecture book, but it read to me like a piece of literature. I found it to be captivating and somewhat Borges-like—not in structure but in its spirit. Then around 2001, there was the publication of The Gray Cloth with Ten Percent White: A Ladies’ Novel. I was struck by its very unusual literary style—very sparse, thematic, and highly evocative—and fascinated by the entire novel, which is about people struggling over the political and spiritual meaning of aesthetics. I had never encountered anything like it in historical literature—the way it speaks in a proto-feminist voice but also with the deep undertone of misogyny that one associates with that era. It was a very disturbing book and it really bothered me—the way in which he demonstrates how aesthetics can have this implication about sexuality. I had so many questions about the translation itself. Later I learned that much of the strangeness of the language lay in the original German.

I had a similar experience with his outer-space novel, Lesabéndio, when it was first published in English. It’s such an epic text, and yet I really couldn’t discern in his writing voice whether it was a very genuine work of a doe-eyed Utopian or a long, laborious joke. All of this effort he put into detailing an asteroid planet and these ridiculous alien characters, the lead protagonist of which transforms into this omniscient, Kubrick-inspired, energy field at the conclusion. Needless to say, I was very confused. How did you come up with the title of the book?

We wanted to demonstrate the breadth of Scheerbart, from novelist to critic to theorist to humorist to philosopher to artist, while trying to situate him in the literary and radical politics of his day. So glass speaks to his forays into architecture as politics, love represents his literature focusing on gender relations, perpetual motion focuses on the poetics of his work in the world of engineering and technology. Our hope was to encourage new translations and further scholarship on him. That’s what my “poem” at the end of the book is about: highly edited groupings of his titles, hoping to inspire new Scheerbartians.

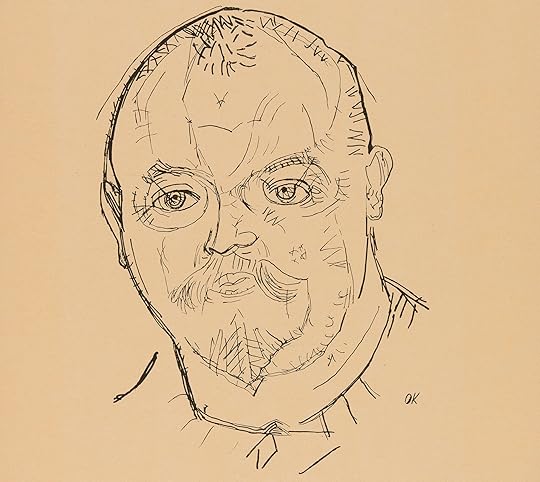

Oskar Kokoschka, Portrait of Paul Scheerbart, 1910. Archive Marzona, Berlin. Photograph: Marcus Schneider, Berlin

In doing all of this archival research, what did you discover about the common cultural perception among Germans of Scheerbart’s eccentric writings?

He was misunderstood in his own age, so it’s difficult to find anyone who has a handle on him, even among German readers. By the early 1890s he was already quite the character—a novelist, an architectural visionary and a science-fiction publisher. Further evidence of his strangeness was that he was a regular contributor to the engineering magazine Technische Monatshefte (Engineering Monthly), at the same time he is being published by these radical, avant-garde literary publications like Der Sturm! It’s fascinating to see how he was able to convince both the engineering world and the most advanced art thinkers of the moment to publish him. When the Wright Brothers arrived in Berlin in September of 1909, in Tempelhof Airport—this is the first appearance of an airplane in Germany—Scheerbart was there. By November, two months later, he’d published an article, “The Development of Aerial Militarism and the Demobilization of European Ground Forces, Fortresses, and Naval Fleets,” which essentially predicted all the possible kinds of death that can be created from planes, missiles, or drones. He perceived all this horrible violent potential within two months. This gave a gravitas, a weight to his thinking, and it was stomach churning. But now, these days, most people end up reading him as if he were only one of these things, for instance a “a science-fiction writer.” When Edition Phantasia republished most of his work in the 1980s, it designed the volumes using a peculiar, neo-art nouveau typeface, totally unlike the modernist aesthetic of the original publications. This shift of tone gives his work a rather countercultural feel, whereas he was truly at the center of things in his own time. Reading him through that lens makes it very difficult to see the other aspects of him.

For me, Scheerbart’s work seems to fall more within that French tradition of fantastique literature in which the fantasists and decadents of the late nineteenth century had begun to encounter and muse on new technologies, architectures, and artificial environments as future utopias. He belongs in the company of writers like Alfred Kubin, Camille Flammarion, Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, Raymond Roussel, Marcel Schwob, Alfred Jarry …

Scheerbart and the others you mentioned were writing right before the mass violence of World War I, which seems to me to completely disrupt history, even now. There were all these new potentials, but then the violence and the economic upheaval of the war period ends that possibility. So when some of these ideas were taken up again just after the war, like the Scheerbart-inspired Crystal Chain group with Taut and Gropius, among others, these efforts almost immediately disintegrate and are then swept under the rug, as if they’d never happened. In some sense, I think we haven’t completely processed what a massive shift—and loss—the war represented. Between 1914 and the 1990s, we’ve still been dealing with the fallout of World War I. Maybe now we’re finally entering a new period where some of the things that were happening at that time, just before the war, can be reexamined.

Paul Scheerbart, Glass Houses: Bruno Taut’s Glass Palace at the Cologne Werkbund Exhibition, March 1914. Technische Monatshefte: Technik für Alle. Baukunstarchive, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

What about this era appeals to you as a visual artist?

What interests me about Scheerbart in relationship to design and literature is the connection between aesthetics and practical construction, all under the roof of literary narrative. After the war, aesthetic theories became divorced from any sense of the literary, or of humor. Rather, everything became, first and foremost, an expression of economics, a demonstration of efficiency. Later, the critique of all this, especially in French theory and philosophy, emphasizes the economic underpinnings and doesn’t seem to remember the literary roots of it. Scheerbart’s moment was one in which technology and design had an evocative potential, a potential that is not fully futuristic but rather changes within an historical context. In contrast, people opposing him or ridiculing his ideas, those who more or less won the argument after World War I, saw starting over from zero as the answer. They thought that the erasure of the past was essential. Scheerbart saw the opposite. His work considers the ideas of the Babylonian era in equal measure with futuristic ideas. Even today, the idea of bringing the past with us into the future is very odd. We’re still in an era of historical forgetfulness as a cultural mode. All new technologies aspire to erase the technologies of just a few years before.

This link Scheerbart develops between the use of glass as both a literary conceit and an architectural prima materia also evokes a link between literature and architecture, which one would see in, say, the work of the early, British gothic writers. The novels of Horace Walpole, for example, or William Beckford are fascinated with constructing elaborate interiors, which they transformed into actual folly architecture at Strawberry Hill and Fonthill Abbey. Could you discern in Scheerbart this frustrated desire to take his written work into the realm of actual, lived space?

This link Scheerbart develops between the use of glass as both a literary conceit and an architectural prima materia also evokes a link between literature and architecture, which one would see in, say, the work of the early, British gothic writers. The novels of Horace Walpole, for example, or William Beckford are fascinated with constructing elaborate interiors, which they transformed into actual folly architecture at Strawberry Hill and Fonthill Abbey. Could you discern in Scheerbart this frustrated desire to take his written work into the realm of actual, lived space?

I don’t think he ever saw himself as a practical builder. He wanted to be part of a community and energize other people. It’s no accident that he met Bruno Taut under the guise of developing a society of glass architects. He didn’t want to be the architect, he wanted to generate the dialogue and supports others. That’s really important in understanding Scheerbart. He wanted the engineering and construction companies to take on the fantastical, to see its potential to change society. Utopia, for him, was based on this idea that average people would take up his ideas—but he’s weirdly self-aware. He writes, “Always and again, this pathetic if … ”—he doesn’t want to accept the “if” or that moving forward can be stopped by simply saying “if only … ”

The Glass House by Bruno Taut, Cologne Werkbund Exhibition, 1914. Baukunstarchive, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

Scheerbart explored glass as a building block not only of construction but also of “seeing,” at this transitional moment between nineteenth- and twentieth-century practices of art and architecture.

One of the things that remains unexamined is the way in which he offers an alternative to the current era of the architecture of transparency. This transparency is the main legacy of the International Style of architecture, which sees glass architecture as metaphorically representing how large corporations move flows of capital across the world in an “honest” way. Even today, the idea that a transparent building is more honest is commonplace among architects, as is the notion that transparency represents a higher morality. This is the architectural, though not political, era we’ve lived through and continue to live in. My interest in Scheerbart is that there might be a parallel possibility where glass is not about seeing through the structure, but rather about how it provides illumination. So, for example, the less well-known “Glass House,” the Maison de Verre, by Pierre Chareau from the 1930s, might represent this other path—it’s an important glass building that’s mostly opaque, or rather, translucent. It’s not about seeing beyond, it’s about being illuminated in the space that one is in now. We’re not going to travel into the far horizon. So, in a way, again, it’s about dragging the past into the future with us.

Erik Morse is the author of Dreamweapon (2005) and Bluff City Underground: A Roman Noir of the Deep South (2012). He is also a lecturer at SCI-Arc, Los Angeles.

The Art of Paños, and Other News

Photo: Reno Leplat-Torti / Paños Chicanos, via Vice

Wackford Squeers, Peg Sliderskew, Charity Pecksniff … are outré enough to put Thomas Pynchon to shame.

Relatedly: naming one’s characters is arguably . “I make up names for people all the time—it’s part of writing. Very often, the name comes with the character, along with of a sense of who they are and what they do … All names are masks, as well as identifiers.”

For her services to literature, Hilary Mantel—with whom we’ll feature an Art of Fiction interview in our next issue—has been made a dame.

Early in the twentieth century, an unlikely duo developed the first mechanistic theory of the mind: Warren McCulloch, “a confident, gray-eyed, wild-bearded, chain-smoking philosopher-poet who lived on whiskey and ice cream and never went to bed before four a.m.,” and Walter Pitts, “small and shy, with a long forehead that prematurely aged him, and a squat, duck-like, bespectacled face.” They asserted that the brain “uses logic encoded in neural networks to compute.”

Finally, without further ado: Mexican prison art. “The tradition of paño (from the Spanish ‘pañuelo,’ which means ‘handkerchief’ ) began in the correctional facilities of Western American States sometime in the 1940s. At the time, decorating handkerchiefs was the only way for illiterate Mexican prisoners to communicate with the outside world. To this day, paños are still often sent to friends and family instead of letters, while, in certain prisons, the handkerchiefs are a popular form of currency.”

February 6, 2015

Staff Picks: Tornadoes, Turf Wars, Time Travel

From Richard McGuire’s Here.

In a New Yorker Talk of the Town from last year, the poet Ansel Elkins sits at an outdoor table at the Standard East Village and watches, she says, “the parade of fine-looking men in suits.” I thought of that line as I was reading her forthcoming debut collection, Blue Yodel. Elkins is from Greensboro, North Carolina (she still lives there), and her poems convey the punishing weather, latent violence, and overgrown beauty of the Southern states. One of my favorites is “Tornado,” in which a woman loses her child to the storm: “I watched my daughter fly away / from the grapnel of my arms. Unmoored, / like a skiff she sailed alone out the window.” Among these measured evocations of sometimes wild places is a rather astute depiction of the city, in the poem “Tennessee Williams on Art and Sex,” which takes its title from a 1975 New York Times review of Williams’s memoirs. (Williams, of course, was another Southerner come north.) “Men in gray suits and hats leap graceful over a water-swollen grate / You stop at a corner bodega to light a cigarette, lean against a crate of oranges,” she writes. The poem also deals dexterously with missed connections: “Tell me again about desire and writing. But you don’t hear me.” —Nicole Rudick

The first page of Richard McGuire’s graphic novel, Here, depicts a corner of an empty living room. A date of the top left reads “2014.” The next page is the same vacant room decorated with floral wallpaper and different furniture, in 1957. Next page, same house, different wallpaper and furniture, 1942. As the book proceeds, McGuire inserts multiple “windows” atop the room: snapshots of that same space across time, sometimes stretching back millennia and jumping two hundred years into the future. We see Lenape Indians joking and flirting in the woods in 1609, the catastrophic rise of sea levels in 2126, carpenters building the house in 1907, the primordial swamps of 8,000 B.C.E. Driven less by narrative and more by the juxtaposition, Here is a collage that pits domesticity and the personal, and even civilization, against the flow of time. McGuire, with his command of the rhythm and texture of images, is onto something concerning the way we perceive the temporal; he said about his recent cover for The New Yorker, “As I walk around the city, I’m time-traveling, flashing forward, planning what it is I have to do … Then I have a sudden flashback to a remembered conversation, but I notice a plaque on a building commemorating a famous person who once lived there, and for a second I’m imagining them opening the door.” —Jeffery Gleaves

J. C. Chandor’s first two films, Margin Call and All Is Lost, were impressive pressure cookers, but neither prepared me for the jolt of his latest, A Most Violent Year, which somehow finds tension and high drama in New York City’s heating-oil business circa 1981. Oscar Isaac stars as Abel Morales, the proprietor of Standard Oil, a thriving but beleaguered company facing turf wars with its competitors, violence against its drivers and salesman, and a slew of indictments from the District Attorney’s office, among other problems. In attempting to solve these, Morales enters a mobbed-up, ethical gray zone, where any victory is pyrrhic and the threat of violence always looms. But A Most Violent Year is not a violent movie: it borrows from crime and gangster films without succumbing to their clichés. As Chandor’s camera takes in the blighted outer boroughs and graffitied subways, success, that most self-evident of goals, comes to feel like a slippery abstraction. “Have you ever thought about why you want it so badly?” Morales’s second-in-command asks him at one point. “I don’t know what you mean,” he replies, with scary sincerity. Isaac turns in a career-making performance: steely and suffering, he can say more with the set of his mouth than many actors do with their whole faces. —Dan Piepenbring

The Robert Miller Gallery has mixed-media work by Ted Victoria on display. Victoria uses projections, lenses, and mirrors, to play with the eye, bringing a sense of otherworldliness to otherwise ordinary subjects. In one piece, he magnifies and projects a jar of krill so you can watch their enlarged bodies swim up and down an adjacent wall. The scene is eerie and enthralling, giving the room a strange luminescence; you could easily spend, as I did, an entire lunch watching the tiny crustaceans. —Lynette Lee

As a national juror for the Scholastic Writing Awards, I spent this past weekend in Hunter College’s computer labs, reading work by high school students, many of whom submitted hopeful, heartening essays about why they consider themselves writers and how writing has shaped them. These reminded me of C. Alphonso Smith’s 1913 book, What Can Literature Do for Me? With chapters like “It Can Keep Before You the Vision of the Ideal” and “It Can Show You the Glory of the Commonplace,” Smith’s tract is an earnest, romantic appeal to the unconverted, but he also draws from exciting and unexpected sources to make his case. “Sometimes the right book startles or warns you,” he writes, “sometimes it takes issue squarely with you … but in every case it reveals something common with you, and on this common basis you rise toward its level.” —Catherine Carberry

Into the Weekend

Elizabeth Bowen

Here are some words to take into the weekend. I have been reading a lot of Elizabeth Bowen lately, prompted first by the gorgeous paperbacks recently reissued by the University of Chicago Press. She needs no praise from me; at her best, Bowen is as unsparing and quietly devastating a writer as exists in English, and any time spent with her novels is time well spent.

She is not definitely cozy—despite her elegiac descriptions of homes, and her memorable child characters—and the worlds she paints are often disturbing beneath their calm facades. You need to be in the right mood for Bowen, and you need to do both her and yourself the favor of investing enough time to fall deeply into the prose, and the landscape. But if you do, you will be richly rewarded.

Bowen is also someone whose work stands up to repeated reading. But due to a certain embarrassing tendency to faint, I’ve been persistently unable to reread The House in Paris since I first tackled it (and duly fainted) as a teenager. And as such, I must thank Suzanne Fischer’s terrific Public Historian blog for reintroducing me to what is probably my favorite Bowen quote. It is as good an introduction to her work as I can think of, and stands on its own. (Although I imagine it’s even better in context. I will never know.)

But for lovers or friends with no past in common the historic past unrolls like a park, like a ridgy landscape full of buildings and people. To talk of books is, for oppressed shut-in lovers, no way out of themselves; what was written is either dull or too near the heart. But to walk into history is to be free at once, to be at large among people. Art does its work even here in clarifying their faces, but they are dead, immune, their schemes and passions are legacies … Outside, the street, empty, reeled in the midday sun; the glare was reflected in on the gold-and-brown restaurant wall opposite; side by side in the empty restaurant, they surrounded themselves with wars, treaties, persecutions, strategic marriages, campaigns, reforms, successions and violent deaths. History is unpainful, memory does not cloud it; you join the emphatic lives of the long dead. May we give the future something to talk about.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers