Victoria Sadler's Blog, page 7

September 29, 2015

Review: Tipping the Velvet, Lyric Hammersmith 'Warm, Witty and Laughs Aplenty'

Venturing into a stage adaptation of a book when you haven't read the book is a bit of minefield. What should I be comparing it to? Sarah Waters' Tipping the Velvet caused waves when it was first published. As did the subsequent TV production. Which I also didn't see. So what was I expecting?

Well, as for all theatre, I was hoping to care. I'm a story junkie at heart and so, yes, I might not have known every detail of this story of a young girl finding the courage to come out as a lesbian in a world that demands she keeps that love hidden, but I wanted this show to make me care about it.

But, oh, this production gives so much more than that! For this is no orthodox retelling of a serious but life-reaffirming story. Instead this stage adaptation is funny, full of energy, and brimming over with bawdy humour, song and dance, and dazzling spectacle.

The opportunity presented by the story's principal setting of a Victorian music hall is grabbed by both hands by director Lyndsey Turner and playwright Laura Wade.

This is very much a show within a show (within another show). David Cardy leads us Emcee-style through the life and times of Nancy (Sally Messham), from her first lustful thoughts for performance artist Kitty (Laura Rogers) through her whirlwind existence in the big smoke - from rejected lover to sex worker, through to kept woman and socialist reformer.

Music hall numbers are effortlessly weaved into the production. But orthodoxy is out the window and instead of the traditional fayre, in comes Prince, Pet Shop Boys, Bronski Beat... There's a bit of Sia, Amy and even Nicki Minaj thrown in too.

The feeling is warm, witty with laughs aplenty - after all, you've got to keep the audience rolling in the aisles. This show is packed full of entertainment, whether it's lovers swinging from chandeliers, or mournful solos whilst hanging from a meat-hook. And everything is thrown in from traditional seaside-style cut out photo boards to dildos, from human ventriloquist dummies to song and dance numbers.

And the performances from the cast match the spectacle, particularly Sally Messham as Nancy. She gives everything to what is an intensely physically demanding role. Her depiction of a working class girl battling both herself and everyone around her is brilliantly conveyed. But there is a beating heart beneath the tough shell and this comes across wonderfully.

The production isn't completely watertight - the story drags In a couple of places, particularly in the final section where Nancy blossoms with her involvement in the Bethnal Green socialist movement - and I suspect some may feel the production is a little too flippant but I'm all for forgiving these as, quite simply, the show does have an emotional impact.

The interpretation is risky, yes, but theatre should be risky. And for all the theatrical spectacle and the clever tricks, you feel for Nancy, you really do. You're rooting for her and at the climax, when she understands what it is she truly needs, it's a great feeling. Tipping the Velvet is a bright, witty production - but it also has a heart.

Lyric Hammersmith, London to October 24, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Sally Messham playing Nancy Astley & company in Tipping the Velvet Photo by Johan Persson

2.Sally Messham playing Nancy Astley & Laura Rogers playing Kitty Butler in Tipping the Velvet Photo by Johan Persson

3.Laura Rogers playing Kitty Butler in Tipping the Velvet Photo by Johan Persson

Published on September 29, 2015 14:31

September 17, 2015

Review: The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern 'Brash, Bold and Exciting'

Like all good Pop art exhibitions, The World Goes Pop is loud, brash and full of colour. But this new show at the Tate Modern is not your typical collection of Warhols and Lichtensteins. Not at all. Instead the Tate is throwing out conventional perceptions of Pop art as an Anglo-American phenomenon and is instead bringing into focus Pop art work from around the world - from Latin America to Asia, from Europe to the Middle East.

How did these artists respond to an art movement that seemed so focused on Western consumerism? And given that many of these countries were not even capitalist in the 1960s, how did they use Pop art to reflect on their own cultures? These are exciting questions and ones the Tate addresses with a wide variety of work displayed in a bold and punchy exhibition.

When you first enter, it's a little overwhelming. There's the noise - many of the exhibits incorporate media. And there are the colours - each wall has been repainted in a bright hue of red, green or blue. And then there's the space. These aren't sedate paintings hung quietly on a wall but art works that invade your space and take over the room.

It takes more than a moment to adjust - but once you do you will discover there are powerful messages wrapped up in these pieces.

American Pop art often focused on advertising and iconic celebrities. But this was also a time when America was at War - either explicitly in Vietnam, or in a stand-off with the Russians. It's interesting then that many of the non-US artists looked to take this movement's artistic focus on consumerism and contrast this with the violence in the world.

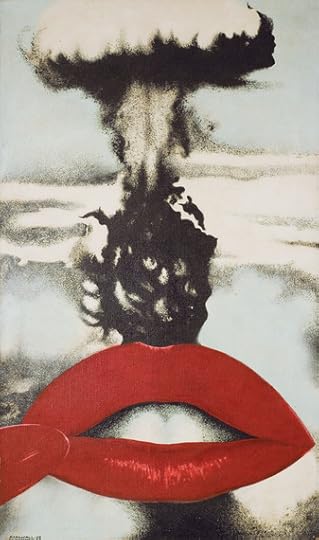

Atomic Kiss, 1968, by Joan Rabascall shows an iconic pair of red lip plastered over an image of an atomic explosion. Whereas Bernard Rancillac's At Last, A Silhouette Slimmed to the Waist, 1966, takes a picture of American troops torturing a Viet Cong soldier and frames it with cut-outs of advertisements for corsets.

Often that political commentary was turned inwards, such as in Equipo Cronica's Concentration or Quantity Becomes Quality, 1966, which looks at mass gatherings in Franco's Spain and how individual acts of protest can solidify into effective collective resistance.

The era of Pop art was also a time for women's liberation and the Tate has included many pieces from female artists who explored the politics and representation of the female form.

Jana Zelibska's immersive work Kandarya-Mahadeva, 1969, takes over one of the galleries. Around the room are large and small outlines of the naked female form. Yet the gaze of voyeurs is challenged by placing mirrors strategically around the female body, on those parts where the gaze may linger a little longer.

Another of her pieces, Breasts, 1967, looks at the eroticism of the female body by taking two representations of breasts and placing one of them behind a net curtain. By this simple act alone, the female body becomes tempting and tantalising despite the fact that the object itself has not changed.

Gender identity itself is looked at in Renate Bertlmann's Exhibitionism, 1973, where the outlines and contours of a female form are juxtaposed with egg-shaped objects, representing male genitals.

What really intrigues though is not just how these artists used Pop art to interrogate their own cultures, but how they also responded to the Pop art headliners from the US and the UK.

The stand-out piece in that regard has to be Cuba's Raul Martinez's Oye America! (Listen America!), 1967. Warhol has his endless repeated images of Marilyn. Here Raul uses the same trick - only this time with a state-approved image of Fidel Castro.

Another series of pictures that impressed were Erro's American Interiors, 1968. The desirability of the American home was a subject addressed by many American Pop artists. Here, Erro has the peaceful, idealised American home being invaded by Viet Cong and Maoist troops.

The Tate Modern has brought together an impressive range of art for this exhibition, and amount too. 160 works in total fill these galleries, and many have never been seen in the UK before. One particular piece, Henri Cueco's Large Protest, 1969, has not been seen anywhere since 1970.

Large Protest was part of a body of work Henri made in response to the May 1968 protests in France, Vietnam and the Cold War. In many ways this one piece sums up the spirit of this whole exhibition - life-size cut-out figures drawn in comic book-style jut out into the room. Many of these figures are suspended just above the floor, making them slightly surreal. Yet in the centre of the group, one of these dream-like figures is punching her fist directly into the air. That spirit of revolution and resistance never far from the surface.

Tate Modern, London to January 24, 2016

Image Credits:

1.Doll Festival 1966 Fluorescent paint, oil, plastic board on plywood. Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art (Yamamura Collection) © Ushio and Noriko Shinohara

2.Joan Rabascall Atomic Kiss 1968 Acrylic on canvas 1620 x 970 mm. MACBA Collection. Barcelona City Council Fund. Photo: Tony Coll © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

3.Evelyne Axell Valentine 1966 Collection of Philippe Axell. Photo: Paul Louis © Evelyne Axell/DACS 2015

4.Kiki Kogelnik Bombs in Love 1962 Kevin Ryan/Kiki Kogelnik Foundation Vienna/New York.

Published on September 17, 2015 15:23

September 15, 2015

Review, Ai Weiwei, Royal Academy of Arts

The Ai Weiwei exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts is a rather sombre affair that brings into sharp focus the scale and impact the Chinese government's attempts at censorship have had on the artist.

There is a strong autobiographical theme running through this exhibition. The artist has placed himself at the centre of much of his work. Many pieces are new, created in the past few years, and often responses to personal experiences such as his detention, where he was held by the Chinese authorities for 81 days and his passport confiscated, or the sudden bulldozing of his Shanghai studio.

Souvenir from Shanghai, 2012, is an attempt by Ai to create art from destruction. It is a tightly packed cube of rubble left from his destroyed studio and set in a wooden frame. The defiance in the work is almost tangible.

And in S.A.C.R.E.D., Ai places himself directly in the art. This work consists of six large dioramas - contained boxes that are faithful reproductions of the cell he was kept in and within each cell is a scene - Ai being interrogated by Chinese officials, Ai being watched over by guards whilst he sleeps.

And where Chinese government censorship affects others, Ai seeks to capture that too. The 2008 earthquake in the Sichuan province killed thousands of people but the authorities tried desperately to hush up the scale of the loss. Ai's Straight, 2008-12, is his attempt to expose that deception, with steel bars reclaimed from the wreckage straightened out and laid out across the floor of one of the large galleries in the RA, with the names of the dead scribed in boards on the surrounding walls.

That mix of Big Brother and rebellion infuses so much of the work on show. Marble sculptures such as Surveillance Camera, 2010, and Video Camera, 2010, reflect what Ai and the Chinese people have to endure, whilst Ai's wallpaper with the middle finger constantly raised in a swirl of repeated images, depicts his refusal to back down.

Ai is a very modern man - he is a prolific user of Instagram and the Twitter logo is featured heavily on another wallpaper pattern that covers the walls of one of the galleries. But he is also interested in Chinese heritage.

In Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, Ai comments on the Cultural Revolution and its destruction of Chinese history for the sake of personal vanity and revolution. Nothing is scared in the pursuit of ambition and economic development.

And the exhibition also contains objects from Ai's Furniture series, which creates contemporary art from antiques, such as Grapes, which is a sphere comprised of 27 stools from the Qing dynasty.

Fragments, 2005, is one of Ai's most ambitious sculptures and builds on the Furniture series. Here, Ai uses pieces from the Ming and Qing dynasties, along with salvage from ruined temples, to create a three-dimensional skeletal outline of a map of China.

The work fills one of the galleries, and visitors are free to walk through it, underneath it, passing around the scrap furniture with ease. Interesting enough - but this piece exists to reflect how tourists to China can move without impediment around the country. Chinese citizens, however, cannot.

Ai's art, you see, gains weight from explanation. The pieces are interesting to observe but not many would consider them masterful technical achievements and, interestingly, they don't necessarily move you. But they are an effective tool in pulling back the curtain.

For most visitors, this will be their first time seeing such a range of Ai's works. This will be their first glimpse of the art behind the artist. What I expect this will reveal to many is that though Ai Weiwei may be the most famous artist in the world, he may not be the best. The question is, does that matter?

As an artist, Ai has made the decision to record what is happening to him, to document his censorship, to record as evidence the attempts by the Chinese government to silence free expression. And as an artist, he is in a unique position to do so.

Without Ai, we would have no insight into such a secret world. No other artist is being subject to this level of suppression. Ai has taken his experience as a witness, as a victim, and is turning this into art to expose and shame the Chinese authorities. Such persistence could have huge repercussions for both China and its people.

Separating the man from his work may be difficult in this instance and, though his pieces may not amaze, they are too important to overlook. There is much to learn and absorb from this vital exhibition.

Royal Academy of Arts, London to December 13, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Ai Weiwei in his studio in Beijing, taken in April 2015. Photo © Harry Pearce/Pentagram, 2015

2.Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 3 black and white prints, each 148 x 121 cm. Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio. Image courtesy Ai Weiwei © Ai Weiwei

3.Ai Weiwei, Surveillance Camera, 2010. Marble, 39.2 x 39.8 x 19 cm. Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio. Image courtesy Ai Weiwei © Ai Weiwei

4.Ai Weiwei, Straight, 2008-12 Steel reinforcing bars, 600 x 1200 cm. Lisson Gallery, London. Image courtesy Ai Weiwei © Ai Weiwei

Published on September 15, 2015 08:51

September 9, 2015

Review: Lest We Forget, English National Ballet 'Devastating, Unforgettable'

Lest We Forget is a powerful and extraordinary collection of three dance pieces that English National Ballet (ENB) premiered in 2014 to commemorate the centenary of the First World War. Universally critically acclaimed, the show went on to win The South Bank Sky Arts Award for Best Dance.

Like many others, I was so disappointed to miss the shows that ran at the Barbican Centre last year so I was genuinely thrilled when the ENB announced a new run. Often having high hopes for a show is not a good idea - that risk of being disappointed - but there's no chance of that with Lest We Forget. Its impact is as devastating as its technical excellence is profound.

Three of the most sought-after choreographers - Liam Scarlett, Russell Maliphant and Akram Khan - were each commissioned to create a piece and the results are a beautiful collection that reflect not just the conditions of the War, but also the impact on both combatants and society. And the blend of modern choreography with the discipline of ballet in each piece adds to their dramatic effect.

Liam Scarlett's No Man's Land opens the show and it is a gripping and innovative performance that shows the effect of the War both on the men sent off to fight, and the transformative effect on the women who were left behind.

The choreography is impressive, with a fascinating contrast between the punishing effects on the men, who become broken and traumatised, and the whirling transformation of the role of women, as they fill the production lines in the factory, rhythmically completing their tasks that are freeing them from the trappings society caged them in before.

There is, of course, something perverse and awful in the fact that women prepared the bullets that their fathers, sons and husbands used to kill the husbands, sons and fathers of other women. And this dance captures that terrible irony so well.

It is though only right that the piece ends on a note of loss. Obviously not all men came home and that is beautifully reflected in a tender pas-de-deux between a woman (Tamara Rojo) and the ghost of her lover who went but did not return (Esteban Berlanga).

The second piece, Russell Maliphant's Second Breath, is a far more emotional reaction to the loss and trauma of war, with no obvious narrative in the choreography.

Leading the dance are Alina Cojocaru and Junor Souza, who I've seen perform before and who I think is a real rising star. And his seemingly effortless power and grace were a perfect foil for the delicate elegance that Alina Cojocaru always brings to the stage. The mix of her fragility and his strength was beautiful.

The finale is the much-lauded Dust by Akram Khan - it won Best Modern Choreography at last year's Critic's Circle National Dance Award - and to see it is to understand why this piece has become so celebrated. It is awesome, it really is.

Tamara Rojo, of course, impresses as the woman waiting at home for her man but it is the physical performance from the two male soloists - James Streetar and Fabian Reimair - that grips you. For this is a piece about the trauma of war, about PTSD. About how a soldier never really leaves the battlefield, even after the war is over.

Each piece is superb but Dust, for me, really brought home that for many soldiers, the war never ends. Dust resonates, it really does. It haunts you. Its impact will stay with you long after the curtain comes down.

This show is running at Sadler's Wells for one week only and, considering its critical acclaim, expect tickets to fly. It then goes on to Milton Keynes and Manchester so catch it if you can. Lest We Forget is an extraordinary blend of dance styles and, when mixed with such a profound emotional impact, it is unforgettable.

Performances:

���Sadler's Wells, London to September 12, 2015

���Milton Keynes Theatre, October 20, 2015

���Palace Theatre Manchester, November 24, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Lest We Forget, English National Ballet. Dancers of English National Ballet in Dust by Akram Khan. © Photography by ASH

2.Lest We Forget, English National Ballet. Tamara Rojo and Esteban Berlanga in No Man's Land © Photography by ASH.

3.Lest We Forget, English National Ballet. Alina Cojocaru and Junor Souza in Second Breath © Photography by ASH.

4.Lest We Forget, English National Ballet. Tamara Rojo and James Streeter in Dust by Akram Khan © Photography by ASH

Published on September 09, 2015 15:32

September 2, 2015

Review: People, Places and Things at National Theatre

What do we look for in great theatre? What is it we see and hear in a show that makes us want to recommend it?

A story that grabs us? Acting that impresses? Is resonance important? What about risk? Theatre, for me, should always take risks. What else? Some look for innovative direction, or impressive production design; others want a soundtrack that rings in their ears even after they've left the auditorium. And above all of this, we've got to care. We've really got to care about what happens.

Well, all of these things are present in People, Places and Things, a co-production with Headlong that has just opened at the National Theatre - a stunning piece of theatre set in a drugs and alcohol rehabilitation centre that explores how on earth we can hold it together in a world that's so full of suffering and hard knocks.

Denise Gough is superb as Emma, a woman battling herself and everyone else as she tries to navigate a path through rehab and out the other side. Emma is in a bad way - her addictions are so profound that they are sabotaging her career, and they've already ruined her relationship with her family.

Only Emma has no intention of letting down her guard, of admitting that she is in desperate need of help. Instead she is determined that the walls she has built around her will stay up and that she'll push through rehab on her terms alone.

Of course that's not going to happen. But Emma is not an entirely sympathetic character. She's narcissistic and spiteful, wilfully lashing out at all who try to help her, especially her assigned Doctor (a perfectly pitched counterweight performance from Barbara Marten who is as calm as Emma is angry).

This is a world of addictions, trauma and tears. But this is too smart a play to be working just on that level. This is a play about identity, about our place in the world and our struggles to come to terms with the sheer scale of our mortality, and questions the point of a life of sobriety when even our existence has so little purpose.

And at the heart of this world is a truly extraordinary piece of acting from Denise Gough. My god, her Emma is unlikeable but my god, you feel for her. By the end you are completely on her side. That she gets you to care so much for someone who is so selfish is a testament to the vulnerability Denise brings to the role.

She is, of course, enabled by some terrific writing from Duncan Macmillan who has created such a complex and complicated woman. But there is also real bravery in his commitment to long, extended scenes. Such is the preference now for short, sharp scenes that it's quite a jolt to sit through 20 minute scenes of just Emma arguing with either her doctor or a fellow patient on her commitment to the program, or whether she is being entirely truthful with her back-story.

But it's a jolt I like. And it works because both the acting and the dialogue are interesting. It might not always be on the edge of your seat stuff but I like that. This is therapy. This is ever decreasing circles we're exploring here. This is the 'slow, slow, quick, quick, slow' dismantling of all the walls we build up around us. I was completely engrossed.

The direction comes from Headlong's Artistic Director, Jeremy Herrin, and it is both clever and bold. The long group therapy scenes and confessional sessions are shot through with injections of vivid, electric hallucinatory spirals where multiple doppelgängers take to the stage to play out the visions in Emma's head. (But are they hallucinations? Maybe they're real - fragments of Emma's experiences. The walls between reality and imagination are very porous in this production).

And this is complemented with some smart production design from Bunny Christie and Andrzej Goulding, which sees tiles from the walls breaking up, evaporating up into the air - representing not just the effect of the drugs but the flimsiness of all the metaphorical walls on display.

If I was being really picky, I would have lopped off the last five minutes. The penultimate scene is a punch to the stomach. It's awesome. Such is the visceral power of this scene I wish it would have ended there, with the horror that the people, places and things that trigger us in our lives, that cause us to panic and quake in fear, are the very people, places and things we haven't got a hope in hell of avoiding.

But this is a small gripe in what is a stunning and emotional production that hits both the heart and the head.

National Theatre, London to November 4, 2015

Image Credits: People, Places and Things by Duncan Macmillan, Directed by Jeremy Herrin. A co-production with Headlong. All photos by Johan Persson.

1.l-r Jacqui Dubois, Denise Gough (Emma), Sally George

2.l-r Denise Gough (Emma), Barbara Marten (Doctor)

3.The Company

4.l-r Jacqui Dubois, Denise Gough (Emma), Sally George

Published on September 02, 2015 12:59

August 31, 2015

James Rhodes, Instrumental: A Powerful Memoir on Child Abuse and Classical Music

With his autobiography Instrumental, James Rhodes may well have achieved the impossible - writing a first-hand account of child abuse and its terrible legacy that is not just desperately needed, but is also readable and, well, even funny.

This book secured headlines for the attempts made to ban it - a challenge that was so severe it took a Supreme Court ruling in May to secure its publication. But though the implications of this trial are huge in what it means for free speech, don't let it define what you think you know about this book for this is a stunningly frank account about not just abuse, but also the healing powers of music. This is a book that is both terrible and beautiful.

James is a popular pianist who is creating a huge following as a result of his willingness to challenge the stuffiness of his profession and make classical music dynamic and exciting. Yet he is also a survivor of child rape for James was repeatedly raped by his gym teacher when he was only six years old.

How James managed to hold it together to write about his experiences I do not know. But as this book demonstrates, James has been in and out of psychiatric wards ever since. There have been very desperate times - suicide attempts, deliberate and unintentional sabotage of relationships and friendships, and a constant battle with a tsunami of emotions that make even the simplest daily tasks almost impossible.

For as James writes "you cannot outrun this stuff. You cannot hide from it. You cannot deny it. You cannot push it down and expect it not to eventually reappear." And this book is a powerful testament to that damage, and how abuse constantly works at destroying the victim, long after the abuse has stopped.

There are dark passages in this book, particularly the episodes of self-harm and James' description of the adults around him unable (unwilling?) to identify the cause of the changes in the young James' personality. And even the responses from some as James, 25 years later, finally starts to confront and open up about his trauma are god-awful.

But as much as this is a book about abuse and mental illness, this is also a book about music. For it was music that saved James in his darkest moments and it is his passion for classical music that gives this memoir its soaring sprit and its sense of hope.

James cleverly weaves this love into the book. Each chapter opens with descriptions on passages of music and composers that have inspired James - a manner that not just brings in music at key moments in James' journey but breaks up the darkness in the writing, making the book easier to read.

On the wonderful Schumann, he writes "[he] was one of several who suffered from severe depression, throwing himself into the Rhine and then, having not managed to kill himself, sectioning himself voluntarily and dying alone and afraid in an asylum."

Whereas on Mozart, James wryly notes "The world's most famous composer. It's quite an achievement and yet somehow one feels Mozart wouldn't have given two fucks." No, he probably wouldn't have.

And suddenly these greats of classical music no longer seem like obscure figures from history who played for the pleasure of the wealthy and elite, but real men with complex personalities, battling huge issues. Suddenly to us they become human, even relatable. And their music becomes relevant all over again.

For those who have seen and heard James playing live, this format may not be much of a surprise as this is very much the way James lays out his concerts. His passion to drag classical music out from the stale and deliberately prohibitive classical music halls leaps off the page as he continues his criticisms of the classical music establishment and talks about his challenges in widening its audience.

And he is funny. James is funny and this book is funny. It's a dark humour, yes, but come on, anyone who can observe about Schubert's Piano Trio that "this is the soundtrack of a man so depressed he started out his student days training to be a lawyer" deserves credit for that.

That James has found a way to build a life for himself beyond the abuse is extraordinary. But this isn't a rose-tinted view that all obstacles can be overcome. Even at the end James confides that "I've no idea if I'm going to survive the next few years."

For child abuse isn't ever something you get over or leave behind. And at a time when parts of society is still trying to tell victims they have taken too long to come to bring their abuse to light, that you can't cast aspersions on the dead, that not every accuser should be believed, James' book could not be more timely.

We need this book. That James found it within himself to write these words down on a page, to endure again what must have been unbelievably traumatic to write and to edit, we should be incredibly grateful for.

Instrumental by James Rhodes available in paperback from October 1, 2015. Also available in hardback and e-book.

James is also touring to accompany the book. His Instrumental show, including readings and anecdotes from the book and live performance, will tour throughout the autumn and winter. Dates and venues listed on www.jamesrhodes.tv

Image Credits:

Cover art from Canongate Books.

Photos of James Rhodes © Dave Brown

Published on August 31, 2015 13:26

August 26, 2015

Review: Benedict Cumberbatch Stars in Hamlet, Barbican Centre

So it has finally opened.

Such has been the unprecedented level of attention on Lyndsey Turner's Hamlet starring Benedict Cumberbatch that you could be forgiven for thinking that this show has already been with us for months. But no, this week the much anticipated show had its press night and we are all free to talk about in in the press without recrimination.

Hurrah!

Only it turns out that there isn't that much to shout about because, whisper it quietly, this Hamlet is fine, it's ok. But it's not great. It's not the unmissable classic that perhaps we all hoped it would be.

Director Lyndsey Turner has created a dynamic, exciting production that's full of dramatic action but light on introspection. Further, this production revolves around a Hamlet that seems to be playing his insanity as a laugh, as a joke to wind people up. It's a brave interpretation of the text but the result is that though there's much to watch, there's little to engage.

We care about Hamlet - or rather we're supposed to care about Hamlet - because he is facing an impossible decision. And the pressure to make that decision is unbearable and increasing all the time. Only in this production, we are denied that journey.

Instead Hamlet's motivation here is unclear and he is confusing.

Benedict's Hamlet is sarcastic, mean, aloof to his girlfriend and vicious to his mother. He also hams up the supposed mental illness for all its worth, causing much laughter in the auditorium as his Hamlet mocks himself up as a toy soldier brought to life just to confuse and baffle those around him.

But Hamlet is a tragedy not a slapstick comedy and the lack of introspection is a loss.

Benedict is a fine, fine actor and I was so looking forward to seeing this intelligent actor wrestle with Hamlet's huge decisions. I wanted to see him weigh up life and death, to battle with whether to fight and die, or live but succumb. Yet the creative decisions made robbed me of this. But credit to Benedict, he commits fully to this interpretation and his performance is athletic and bold, and his vocal projection is impressive.

But frustratingly, if the creative decision was for Hamlet to play up his madness deliberately, it's not clear why this is done. What is Hamlet trying to gain? What is he trying to achieve by this? That drive to avenge his father comes and goes - and goes more often than it hangs around. It makes him petulant and juvenile.

And when combined with this Hamlet's genuine shock at seeing his father's ghost and his, seemingly, quite tender remorse for Ophelia, the performance doesn't seem to hang together. If he wants to avenge his father then his actions make no sense. Why play mad? And it all seems so incongruous with the reflective, contemplative Hamlet that starts the show.

It's a shame as this Hamlet doesn't seem to care about anything. Even towards the climax, as he's being led away in handcuffs, he doesn't seem particularly bothered. As if he doesn't care what happens to Denmark. Well, Hamlet, if you don't care then neither will we.

As a result, it's so hard to get an emotional 'in' to this production. There's nothing to hang on to. Instead the tragedy is left to Ophelia in a quite beautifully fragile performance from Sian Brooke. Her unravelling is the most heart-rending moment in the production but, of course, it comes so late in the play when most of the damage has already been done.

What doesn't disappoint though is the set.

The set design from Es Devlin is stunning. Breath-taking, in fact. A huge fading baroque Danish palace dominates the set - its high ceilings towering above the cast underneath as they play out their dramas in a palace of dust and dying flowers. It's beautifully atmospheric.

And its dramatic destruction as the borders of Denmark are invaded is a fine piece of theatre. But, let's be frank, when the best thing about your production of Hamlet is the set, you've got problems.

Of course, none of this is probably relevant in a show which could have sold itself out five times over. And probably more.

No doubt the crowds who flock to see the Cumberbatch will come away with different views on the show from mine. And that's great - I really hope they enjoy the production. But, just as importantly, I hope those new theatre-goers amongst them come back to see more shows as the more shows that generate this kind of excitement, the better.

It's worth noting though that if your tickets are on the left-hand side of the auditorium, you may find yourself with an unadvertised restricted view ticket - as we did. Some of the key action takes place in the extreme left wing of the stage. Considering the eye-watering prices for some of these tickets, that's a little cheeky. And another disappointment.

Barbican Centre, London to October 31, 2015

Hamlet will also be shows in cinemas via NT Live on Thursday October 15, 2015.

Image Credits:

1.Benedict Cumberbatch (Hamlet) in Hamlet at the Barbican Theatre. Photo credit Johan Persson

2.Benedict Cumberbatch (Hamlet) in Hamlet at the Barbican Theatre. Photo credit Johan Persson

3.Benedict Cumberbatch (Hamlet) in Hamlet at the Barbican Theatre. Photo credit Johan Persson

4.Anastasia Hille (Gertrude) in Hamlet at the Barbican Theatre. Photo credit Johan Persson

5.Siân Brooke (Ophelia) in Hamlet at the Barbican Theatre. Photo credit Johan Persson

Published on August 26, 2015 11:58

August 19, 2015

The Poise and Beauty of Audrey Hepburn the Focus in New Photography Exhibition

Audrey Hepburn: Portraits of an Icon is a major new photography exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery that truly spans the life of this enduring star, from her early years in the Netherlands, through her years in London on the West End stage and then on to the height of her fame as an actress and fashion inspiration, and her later philanthropic work.

The breadth of coverage in this exhibition is impressive, with rare family photographs included alongside portraits from some of the leading photographers of the 20th century, such as Richard Avedon, Cecil Beaton and Irving Penn.

Incredibly the National Portrait Gallery has even managed to secure the display of some photographs that have never been seen in the UK before, including an early photograph of a nine-year-old Audrey dancing that has been lent by Audrey's sons and the Audrey Hepburn Estate.

The photographs that really grab though, mostly because of their lack of formality, are dressing room shots of Audrey getting ready before performing Ondine on the West End stage, and a photoshoot by Henry Clarke for Vogue in 1971 that shows Audrey playing with sheep.

Of course the formal portraiture impresses - Audrey was so ridiculously photogenic, and her nipped in waist and coy glances played up to a certain desirable notion of femininity.

But the more interpretative ones interest the most, such as Richard Avedon's shot from 1953 with exaggerated high contrast that seems to reduce Audrey's face to its core elements of wide eyes and sharp cheekbones and jawline. This duality between light and dark in this image intrigues, conjuring up thoughts of life and death, even immortality.

As well as the photographs - formal and informal - there's a wonderful wall of vintage magazine covers that show Audrey the cover girl from the 1950s right up to the 1990s - evidence of Audrey's enduring appeal.

But what you notice as you wander past these 70 photographs of the icon, is how little of herself she gave away. In almost every photograph, Audrey's look is the same - mouth closed, bambi-eyes wide open and gazing down the lens. It's the same look, every time.

It's curious and fascinating. This is how she chose to present herself - an iconic look, yes, but Audrey is a firmly closed book. Unwelcoming, almost. Allowing us no further than to look at her, revealing nothing of her emotions, of her state of mind.

And around her, portrait photography was undergoing something of a revolution. The formal portraiture of the 1940s gave way to a more fresh and informal style in the 1950s. Then changing once again into high fashion mode in the 1960s.

Yet even as photography changed, Audrey' expression did not. Her face, her gaze, curiously timeless in a world of great change.

Of course this look, both intelligent and innocent, worked wonders in certain roles, in particular Breakfast at Tiffany's where the studio was keen to downplay Capote's depiction of Holly as a prostitute. First choice for the role for Capote, of course, was Marilyn - and you can just tell how Marilyn was a far more appropriate fit to the character in the book. Not for the studio though, which made Audrey's innocence more appealing that Marilyn's more dangerous instability and sexual allure.

Audrey Hepburn is unquestionably an icon and the popularity of this exhibition is a testament to her draw, even today. Yet, personally, I like my icons to be dramatic, to reveal something of themselves. There's nothing of that with Audrey. Everything is a smooth surface with no ripples in the water. Nothing to betray what is going on underneath.

We respond to portraiture because of what we learn about both the sitter and the artist, and for what it can reflect back at ourselves. And pretty as these photographs are, even after looking at over 70, nothing is truly revealed about this woman whose face we know so well. She remains an elusive beauty.

National Portrait Gallery, London to October 18, 2015

Admission Charge: £10, including voluntary donation. Concessions available.

Image Credits:

1.Audrey Hepburn photographed wearing Givenchy by Norman Parkinson, 1955. Copyright: Norman Parkinson Ltd/Courtesy Norman Parkinson Archive

2.Dance recital photograph by Manon van Suchtelen, 1942. Copyright: Reserved

3.Audrey Hepburn by Antony Beauchamp, 1955. Copyright: Reserved.

4.Audrey Hepburn by Philippe Halsman for LIFEmagazine, 1954. Copyright: Philippe Halsman/Magnum Photos

Published on August 19, 2015 11:48

August 16, 2015

Abi Morgan's Splendour Delights at the Donmar

Hallelujah! Josie Rourke has finally staged an original play written by a woman at the Donmar Warehouse. Until now, all the original works staged during her tenure have been written by men. But now we have Splendour, an early work from the very talented Abi Morgan (Suffragette, The Iron Lady) and it's a gem.

Splendour tells the story of four women. Four women, in one room, in one evening.

The room is in the palatial residence of an absent dictator in an unnamed country. Waiting for him is his wife Micheline (Sinead Cusack) and Kathryn (Genevieve O'Reilly), the Western photojournalist commissioned to take his photo.

Only the dictator in question is running very, very late. And the sounds of gunfire from the streets outside and rumours of revolution swirling in the air tell us that something has also gone very, very wrong.

But Micheline is adamant the photos will be taken. So, to entertain - and distract - her guest, she employs her long-suffering friend Genevieve (Michelle Fairley) to lend the room an air of conviviality and keeps a young woman, Gilma (Zawe Ashton), nearby as translator.

But shouldn't the women flee instead? With the revolutionaries heading for the residence, for how much longer can this masquerade be played? Kathryn is perplexed at these women, seemingly in denial about the war being waged on the streets. Frustratingly she can't even speak the language yet she begins to gauge what is going on in the room. We watch as she watches, reading the body language, beginning to understand perfectly what is being played out in front of her.

The vodka is poured, the gunfire gets closer. And under this pressure, the secrets begin to tumble out and facades start to fall. The end is drawing near and, eventually, each of these women is going to have to make a life-defining choice.

The writing from Abi Morgan is excellent. Complicated and creative. The same scenes replay again and again, but from different perspectives, the increasing alcohol levels and encroaching gunfire subtly but profoundly changing the way the scene is replayed.

The acting from all four women is excellent. There's a tendency to stereotypes in the writing - the icy dictator's wife, gritty photojournalist and opportunistic translator trying to grab anything she can from the palace to sell on the black market. But each of the actresses brings depth and nuance to lift each character from the page and make them engaging, believable. Three-dimensional.

Sinead Cusack dominates the room as Micheline, the absent dictator's wife. There's something of the Imelda Marcos about her Prada shoes and perfectly groomed appearance. But it's the shadows behind the eyes that makes Sinead's performance so good. This is not a woman in as much denial as she seems.

And Michelle Fairley was given a bit of hospital pass as the seemingly fragile Genevieve but she infuses the character with a steely determination and the shifting power dynamic between these supposed best friends - a friendship based on secrets and lies - is the attention-grabber in the production.

Direction comes from Robert Hastie and it is tight and smart. Shame we couldn't have had a female director directing a play about women written by a woman but hey, I guess that was too much to ask. One day perhaps this will become as acceptable as men directing plays written by men about men. One day.

But nevertheless, how good it was to see a play about power and human fallibility told from a female perspective. Dear Donmar, please don't leave it so long again to platform a female playwright. We need to embrace diversity.

Donmar Warehouse, London to September 26, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Genevieve O'Reilly (Kathryn) and Sinead Cusack (Micheline) in Splendour at the Donmar Warehouse - photo by Johan Persson

2.Genevieve O'Reilly (Kathryn) in Splendour at the Donmar Warehouse - photo by Johan Persson

3.Sineaad Cusack (Micheleine), Michelle Fairley (Genevieve) and Zawe Ashton (Gilma) in Splendour at the Donmar Warehouse - photo by Johan Persson

4.Michelle Fairley (Genevieve) in Splendour at the Donmar Warehouse - photo by Johan Persson

Published on August 16, 2015 09:15

August 12, 2015

Review: 'Soundscapes', National Gallery - A Disappointment

For their exhibition, Soundscapes, the National Gallery commissioned six musicians to create music, a sound installation, to accompany six paintings from the Gallery's permanent collection.

Sound as an art form may not be anything new, but creating specific music and sound that facilitates experiencing classic paintings with fresh perspective is an intriguing proposition. Sadly, what was an interesting idea fails to enthral as the commissioned works largely fall flat.

Placing music accompaniment with any painting is always risky as not only can it narrow interpretation, 'forcing' the viewer to observe the art through how the musician has interpreted it, but there's always the risk of the combination jarring and making it impossible to concentrate on either. (I feel that way any time I'm at Tate Britain during its Friday Lates events when they have DJs playing drum & bass when I'm trying to look at Turner. The two just don't work in harmony.)

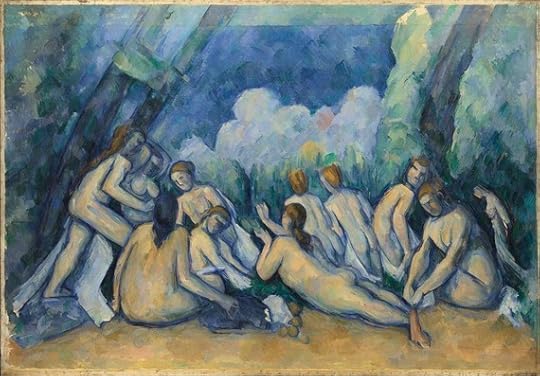

And that is certainly what has happened with Gabriel Yared's dark, gothic score that he created for Les Grandes Baigneuses. This beautiful Cezanne, with its warm skin tones and harmonious group scene, just does not complement a musical score that haunts and chills. The music was so incongruous with the art that I actually couldn't stay and admire the painting for long.

But actually the more common failing in this exhibition is that the scores created are uninspiring and bring nothing new to the pieces of art.

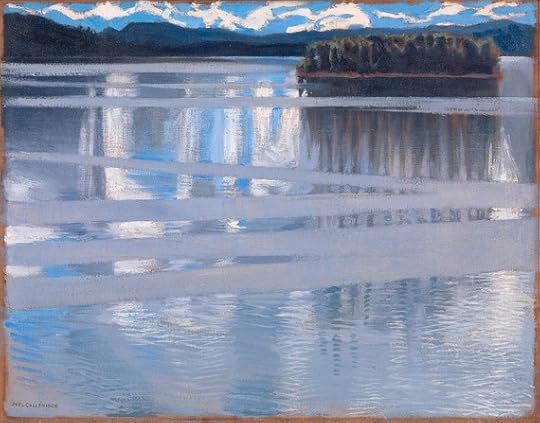

Chris Watson had the serene Lake Keitele by Akseli Gallen-Kallela to work with and he chose to recreate the sounds of a lake in his installation. There's bird song, breeze rippling across still water and all the sounds of a forest landscape. Pleasant but not revolutionary.

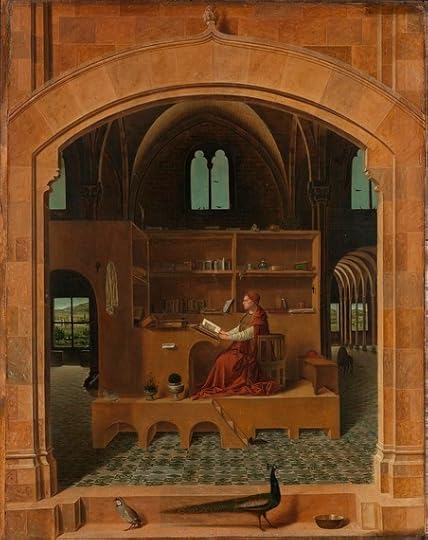

Similarly, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller pulled out every single visual reference in Antonello da Messina's Saint Jerome in his Study and turned it into a sound - there's the sound of people messing about on the river, taken from the painting's background, as is the sound of workers in the field, and all accompanying the dominant sound of reverent choral voices. It's a literal audio walkthrough of the painting, not a re-examining of it.

A similar fate has befallen Hans Holbein's The Ambassadors. Susan Philipsz has taken the visual reference of the lute in the paining and composed a sound installation based around a violin.

But there is an exception - thankfully.

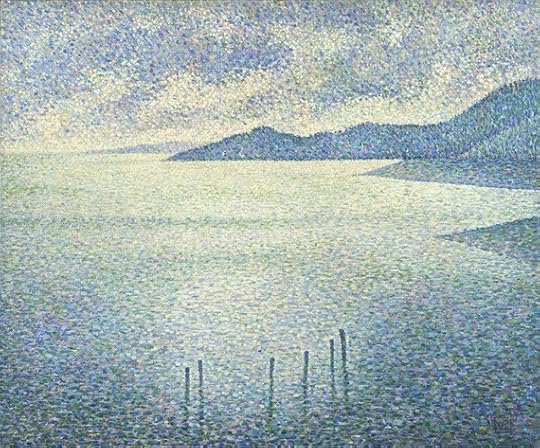

Undoubtedly the stand-out piece of work comes from Jamie XX, who used the pointillist style in Theo van Rysselberghe's Coastal Scene as a launch-off point for his soundscape.

Jamie's work is comprised of electronic beats, each note an aural interpretation of each dot of paint on van Rysselberghe's canvas. And like the painting, the sound is different depending on your proximity to the picture - you stand farther away, the music is harmonious, like the painting. You don't focus on the individual tiny dots of paint and sound. But as you approach the painting, the sound breaks up - the harmony is lost and the distinctive sound of each beat, like each daub of paint, is clear.

Jamie's sound installation, called Ultramarine, is an undeniable success. Finally we have a piece of work that doesn't look to literally recreate the sounds that you'd expect if you were in the actual location of the painting, but instead interprets the art, examines it, and creates a sound that encourages us to examine the painting from a different viewpoint. If only more had taken up his interpretative angle, the exhibition would have captivated more.

Sadly, and probably understandably, this exhibition was not well attended when I visited. It's certainly a curious choice of exhibition for peak tourist season. But though this show may not be a resounding success, there was an unexpected benefit.

The empty galleries meant that I had these six beautiful paintings almost entirely to myself - a rare luxury. To pay £10 to stand alone with these six pieces of art, well, for me it was actually worth it. Probably not for the reasons that the National Gallery was aiming for though.

National Gallery, London to September 6, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses) Paul Cézanne about 1894-1905 © The National Gallery, London

2.Lake Keitele Akseli Gallen-Kallela 1905 © The National Gallery, London

3.Saint Jerome in his Study Antonello da Messina about 1475 © The National Gallery, London

4.Coastal Scene Théo van Rysselberghe about 1892 © The National Gallery, London

Published on August 12, 2015 11:50