Victoria Sadler's Blog, page 9

June 29, 2015

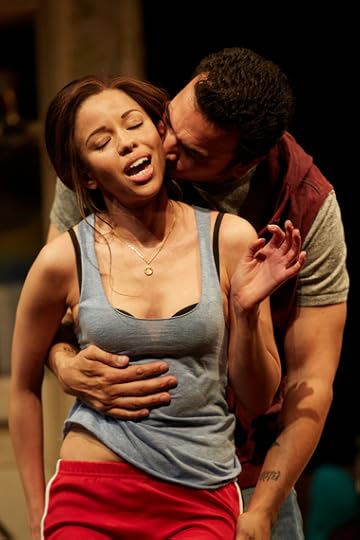

Review: 'The Motherf**cker With the Hat', National Theatre

For a while now I've been wondering why I go to the theatre. I think it was a Twitter hashtag or meme that started it. "I go to the theatre because _" and you fill in the blank. Only I don't know what my blank is. My love for the theatre is so instinctive, so reflexive, I find it hard to examine.

Do I go for entertainment? Or am I searching for some kind of insight into the human condition? I suspect it's both. Insight is nothing if it's dull or patronising. And if it's just entertainment for entertainment's sake, well, [insert derogatory comment about most Saturday evening television shows here].

And then The Motherf**cker with the Hat turns up. A transfer from Broadway that I knew very little about but, in one show, crystallises what I love so much about theatre.

Its premise is simple but layered with complexity. Jackie (Ricardo Chavira) is out on parole and back in the arms of the woman he's loved since he was a teenager, Veronica (Flor De Liz Perez). And this time he's going to make a go of it. He's given up the drug dealing for a job as a security guard and he's got a sponsor to help with his addictions. This time he's going to get it right.

Only, on a dime, his life spins once more into chaos. For there, on the table in his girlfriend's apartment, is a man's hat. And it's not his. Nope. This hat belongs to the motherf**cker in the flat below. So what's it doing in Veronica's apartment?

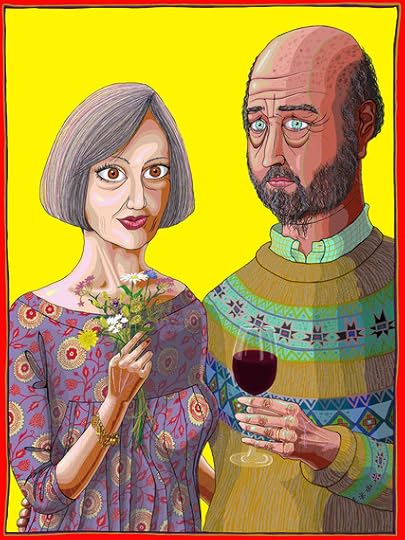

The trigger is pulled and Jackie's rage, jealousy, anger and insecurity spiral out of control. And instead it's left to his sponsor Ralph (Alec Newman), who's having issues of his own with his unhappy wife Victoria (Nathalie Armin), and his estranged cousin Julio (Yul Vazquez), to desperately keep him from doing something bad, from violating his parole and ending up back where he started.

At the core of this story is this - what behaviour do you accept in others around you, and what do you reject? What can you forgive - and when is it finally too much? And this is a play that raises questions but also plucks at the heartstrings. Because by the end, it will have held your heart in its hands - and then broken it.

Let's just say this straight out the gate - the writing in this play is simply awesome. Stephen Adly Guirgis has crafted such a tightly weaved plot with twists and revelations - funny as well as dramatic - tumbling out throughout this play. It never ends. The snippets, the little glimpses into the characters' pasts and fears continue right up to the end. It's beautiful.

And the writing is brought to life by a stunningly good cast. My, they are superb. Ricardo Chavira shines as Jackie in his London theatre stage debut, bringing flesh to the bones of this unlucky everyday guy who, fresh out of jail, is just trying to start over.

It's Yul Vazquez as Cousin Julio who walks off with the audience's heart though. Nominated for a Tony for his performance in this role on Broadway, Yul gives such a feisty but tender portrayal as Jackie's eccentric gay cousin.

It could have been a minefield of clichés and, in other hands, an excuse for some pretty hammy acting. But not here. Cousin Julio has been added to bring most of the laughs, yes, but there is such a strong sense of tribal loyalty and brotherly love in this performance that it only enriches the production rather than overshadows it.

And all of these terrific ingredients are gently whipped together by director Indhu Rubasingham into an impressive production that lays bare the trials and tribulations of these damaged souls against a gritty backdrop of the relentless and unforgiving New York.

And that's why I love this play. Because it's about everything and nothing. It's just a day in the lives of five people in New York yet it forces you to question yourself, to examine your own moral code. What would you have done if you were Jackie? And where do you draw the line?

And isn't that what theatre is all about?

National Theatre, London to August 20, 2015

Image Credits:

1.l-r FLOR DE LIZ PEREZ (Veronica) & RICARDO CHAVIRA (Jackie) in The Motherf**ker with the Hat, National Theatre. Photo by Mark Douet.

2.l-r RICARDO CHAVIRA (Jackie) & YUL VAZQUEZ (Julio) in The Motherf**ker with the Hat, National Theatre. Photo by Mark Douet.

3.YUL VAZQUEZ (Julio) in The Motherf**ker with the Hat, National Theatre. Photo by Mark Douet.

4.l-r ALEC NEWMAN (Ralph) & NATALIE ARMIN (Victoria) in The Motherf**ker with the Hat, National Theatre. Photo by Mark Douet.

Published on June 29, 2015 11:25

June 24, 2015

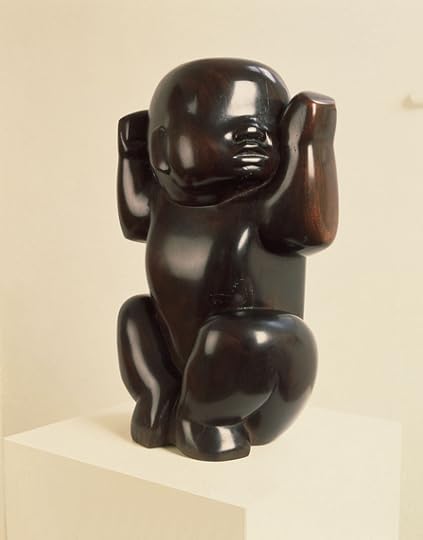

Review: Barbara Hepworth, Tate Britain - A Great Sculptor, But Not a Great Exhibition

When I wrote my list of Top 10 art exhibitions to see in London in 2015, I had this Barbara Hepworth exhibition at Tate Britain at the top of the list. And though the pieces on show are a testament to this artist's extraordinary skill and unique talent, this exhibition does not show her work at its best.

This exhibition, the first major London retrospective of Barbara's work for almost 50 years, aims to chart her development from carving simple, small figures to her trademark large abstract forms. All well and good. And the pieces on display include some gems, but the vast majority of the works are displayed in alienating glass cases within austere rooms.

Barbara Hepworth was inspired by her landscape. She loved how she was carving out stones and wood that nature had already shaped before her. Her pieces are nurturing, soulful, and seem so inextricably linked to the earth. What a shame therefore that the dusty cases and bare walls are a million miles away from the protective landscapes she so admired.

The exhibition also isn't helped by its earlier rooms focusing so much on work other than Barbara's. The first room is filled with tiny carvings (in glass boxes) from a range of artists including Henry Moore, Jacob Epstein and other less well-known sculptors.

The objective I sense was to set the scene of where sculpture was in the 1920s when Barbara first started. But this is all very unnecessary in a retrospective on a specific artist and actually gives the impression that the curators simply didn't have enough pieces from Barbara to fill all their galleries.

But it was the second room that irritated me most - a room dedicated to Barbara's relationship with Ben Nicholson, her second husband.

The justification is an attempt to show how Ben Nicholson's work influenced Barbara's - as if he painting faces actually encouraged her to use faces and figures in her work. Hardly revolutionary and, worse, the effect is to undermine Barbara completely by defining her by who she was in a relationship with rather than on her own terms.

This keeps happening to female artists and just never happens to the men. I found it deeply infuriating. I am thrilled, for example, that the Sonia Delaunay exhibition at Tate Modern focuses on Sonia's work with minimal mention of her husband Robert. Such respect is not afforded to Barbara here. The argument that Ben profoundly influenced her work is not made and instead just seems to be an excuse to put some pictures on the wall.

Even Barbara herself has said of her relationship with Ben, "it was a very splendid cooperation. We were very stern critics of each other's works, and yet felt absolute independence." So why compromise that independence like this?

The last few rooms are unequivocally the strongest. Not only has Barbara honed her work into her trademark style - large pieces of wood and bronze carved out, interiors created and painted, and the light and shadows left to articulate the space created - but the glass boxes are gone and the sculptures have space.

In particular, the walls in the last gallery have been decorated with photographic prints of trees and greenery to recreate a sense of the Pavilion, Barbara's 1965 retrospective at the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands.

Transporting the visitor out of the gallery and into the open air, demonstrating how Barbara immerses her work within architecture and natural landscapes, makes this the best room in the show but it's also a sobering reminder that many of Barbara's pieces are best seen amongst nature, not in glass boxes in galleries. If only similar effort had been made with other rooms in this exhibition.

That the Tate decided to put on a retrospective of this great sculptor is admirable but the resulting show does the artist and her work few favours. I guess it's a trip to St. Ives if we want to see Barbara Hepworth's extraordinary works at their best.

Tate Britain, London to October 25, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Barbara Hepworth Pelagos 1946 Sculpture Elm and strings on oak 430 x 460 x 385 mm Tate © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

2.Barbara Hepworth Infant 1929 Sculpture Wood 438 x 273 x 254 mm Tate © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

3.Barbara Hepworth Sculpture with Colour (Deep Blue and Red) (6) 1943 © The Hepworth Estate

4.Barbara Hepworth Curved Form (Delphi) 1955 ©The Estate of Dame Barbara Hepworth

Published on June 24, 2015 16:00

June 21, 2015

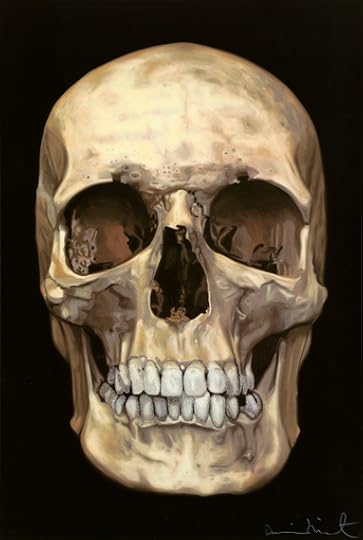

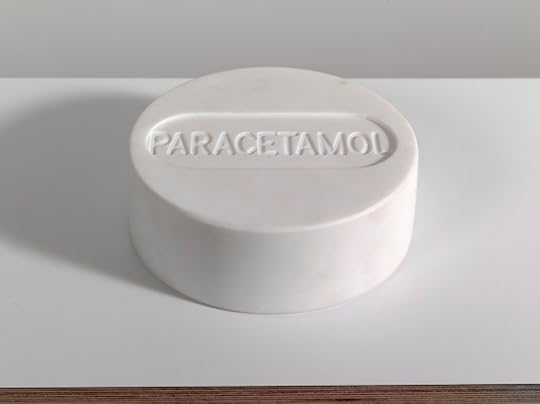

Is Science Our New Religion? Damien Hirst at The Lightbox, Woking

New Religion is a rarely seen exhibition of a body of Damien Hirst's works from 2005 that provokes the question, has science become our new religion?

Silkscreen prints, sculptural pieces and paintings are laid out like Stations of the Cross, around an altar, with a series of surgical images of a body scarred with stigmata-like wounds hung above the visitor, in place of the crucified Christ.

And each image, each station, replaces a scene from Jesus' journey to crucifixion with a drug, for example paracetamol (the purity of white - evocative of both life and death) or Tylenol, another headache tablet (in the more subdued and reflective blue), and a reference to a bible verse, moving from Creation to The Last Judgment.

The message that we have replaced a blind faith in religion with a blind faith in science - all in a desperate, and arguably futile, attempt to avoid death and suffering - is clear. And the works on show include some of the iconic imagery that have become Damien Hirst trademarks, such as the skull and the butterfly, representing metamorphosis and new life.

There's a lot in these works. Each Station is loaded with meaning, whether it's in the pharmaceuticals chosen, the colour palettes deliberately picked or the Bible verses referred to in each print. And The Lightbox has admirably done a lot to help visitors with leaflets available to help interpret the pieces, as well as the provision of bibles and pharmaceutical reference books.

But whether you use these or not, Damien Hirst's message on what has become the New Religion is unequivocal. But, as Damien talks about in a video interview that runs on loop outside the exhibition, our veneration of science is quite bizarre, for even if we avoid disease and illness, we are still going to die. There is no getting out of life alive, so what are we chasing?

And as Damien demonstrates quite beautifully in The Holy Spirit, a scientific pie chart that splits the Holy Trinity exactly and perfectly into three equal slices, representing the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, where is the room in that set-up for individual choice? In a religion which wholly worships either deities or science, what room does that leave for human endeavours and sprit? Is our soul truly irrelevant, whichever religion we worship?

Our complex relationship with death, and our reactions to it, is a recurring theme in Damien's work and well represented here. Congratulations to The Lightbox for obtaining permission to show this exhibition as this is the first time these pieces have been on display in the UK for 10 years, and the first time they have ever been shown outside of London so grab the opportunity to see these works if you can as it does not come around often.

The Lightbox, Woking, Surrey to July 5, 2015

Image Credits:

1.The Skull Beneath the Skin (2005), Courtesy Paul Stolper Gallery © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2015

2.The Eucharist (2005), Courtesy Paul Stolper Gallery © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2015

3.The Soul on Jacob's Ladder (2005), Courtesy Paul Stolper Gallery © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2015

Published on June 21, 2015 07:55

June 17, 2015

Review: Marianne Jean-Baptiste Stars in 'Hang', Royal Court Theatre

What is hang about? I cannot tell you. What happens in it? Even after watching it, I do not know for sure. Everything in this play is a little elusive. Facts, motivations, even names, place and time. Yet this is a play that plunges headlong into a dark situation where victim's justice is taken to its farthest point.

Three people are in a room and one of them has to make a decision. A crime has been committed and a choice has to be made. But the person who has to make that decision (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) is a stranger to the room. She has been invited there, to a room that she does not know. And she has come alone.

The other two characters (Claire Rushbrook and Shane Zaza) know the room, it is their office. It is their territory. They want to know the woman's decision. But they are also keeping secrets from her, shards of information - facts and figures - that she needs to know but they cannot tell. Or shouldn't tell.

But the woman isn't going to tell them her decision until she knows what they are keeping from her. Something is going to have to give.

Sharp, fast dialogue snaps back and forth. Games are played and characters are played off one another with deliberate intent to manipulate and outmanoeuvre. But there is also frailty and doubt, apology and sincere pity. Everyone here is hurting, everyone here is a little insecure.

The three characters are never named. Their backgrounds never described, their roles in the room never clearly laid out. The incident at the heart of the debate is never explained. And, of course, what fills this void is the feverish leaps of the audience's imagination.

Who are these people? What did they do? What has happened before this? How do they know each other? Where are we?

It is an extraordinary achievement from writer and director debbie tucker green that the feverish attempts by the audience to solve this puzzle doesn't dim for one second of this 70 minute production. Right to the end, our minds are frenetically trying to piece together this incomplete jigsaw, leaping to conclusions only to find ourselves in a dead-end, with an incorrect assumption, and having to remap it all out again.

The ending is clever, being both satisfactory and completely unsatisfactory at the same time. To reveal any more would be to betray part of this journey that I urge you to experience for yourselves.

But what this play feels like is a warning. The characters are all modern, contemporary, but the situation isn't today. This play feels like it is set in the future but not that far away. Possibly only tomorrow.

This near-futuristic dystopian feel is reflected beautifully in a striking set from Jon Bausor. Strip lighting fizzes above a stark, bare room. Yet the walls are reflective plastic sheets that shake and tremble ever so slightly, giving the impression of a world that could be real, could be just an apparition. A dream - or a nightmare - of what could come to pass. A nightmare that if you were to reach out to touch it, could melt away and evaporate.

But there's no doubting the extraordinary performance at the heart of this play. Marianne Jean-Baptiste. What can I say? The talent, the craft that woman has is awesome. Just awesome. She is the one that has arrived at this office for reasons that are not explained, she is the isolated one in the room, and she is the one who must make this unspeakable decision.

Marianne's hands tremble but her voice rarely falters. Her shoulders weigh heavy with the pain she is feeling but when she accuses, she never lets her gaze drop from those she attacks. Her portrayal of this woman is filled with complexity and contradictions, a brilliant manifestation of the tangled web of emotions that this woman must be feeling. It really is superb. And so understated.

hang is a stunning piece of theatre. Writer and director, debbie tucker green has not just created a fascinating, gripping piece that examines revenge, suffering and human frailties, but she has shown it at its most foreboding.

Royal Court Theatre, London to July 18, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Marianne Jean-Baptiste (Three). hang, written and directed by debbie tucker green, Royal Court. Photo credit Stephen Cummiskey.

2.Shane Zaza (One), Claire Rushbrook (Two), Marianne Jean-Baptiste (Three). hang, written and directed by debbie tucker green, Royal Court. Photo credit Stephen Cummiskey.

3.Shane Zaza (One), Claire Rushbrook (Two). hang, written and directed by debbie tucker green, Royal Court. Photo credit Stephen Cummiskey.

4.Claire Rushbrook (Two), Marianne Jean-Baptiste (Three). hang, written and directed by debbie tucker green, Royal Court. Photo credit Stephen Cummiskey.

Published on June 17, 2015 11:54

June 15, 2015

Review: Oresteia, Almeida Theatre 'Gripping, Relevant'

Greek tragedies are an unbelievably tough challenge for modern audiences - everything is literal, characters say what they mean, and the Gods are involved in everything. But these stories of revenge, questioning whether violence can ever be justified, are deeply entrenched in our culture, and arguably as relevant now as they have ever been. So, how to put on these stories and make them interesting?

Well, the Almeida has responded to this challenge magnificently with a gripping production of Aeschylus' Oresteia that not only dramatically re-examines this famous tale, but yet also claws away at its central theme of whether 'an eye for an eye' can ever be just.

Agamemnon (Angus Wright) is a weary King. The long running battle with Troy shows no sign of ending. And he is desperate for this war to end - as are his people. But when he prays to the Gods, they return with a simple message - "the child is the price."

Interpreting this to mean he must sacrifice his youngest daughter, Iphigenia (Amelia Baldock), Agamemnon battles with his conscience before accepting that he must do what is necessary, committing a crime that shocks his wife Klytemnestra (the superb Lia Williams) and one that will lead to a cycle of violence and revenge that will destroy his family.

And all the while, separate and running parallel to this famous story, is the fascinating voice of Orestes (Luke Thompson), Agamemnon's son, deeply involved in a session with his therapist (Lorna Brown) as he battles with the fact that his own terrible fate was sealed the moment his father killed his sister.

The central story is legend but it has been given an energetic and passionate new lease of life in this production from director Robert Icke and dramaturg Duska Radosavljevic, and the result is a show that is dynamic and challenging with dialogue that is believable and relevant. And thankfully they've even managed to break up the tragedy with humour in places.

It's not just the story that has been overhauled but the production design too. Out have gone the Grecian robes and sandals to be replaced with a sparse set and simple, contemporary clothes. In fact, if anything, my only gripe with this show is that, if you stopped the actors from speaking, you could be forgiven for thinking you were actually watching Ivo van Hove's revolutionary A View from the Bridge, which opened at the Young Vic last year.

Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery but this does go a bit far at times. The stark white set and lighting, the characters dressed in cool muted tones of greys and creams, even the benches around the edge of the stage where some of the characters will sit with their backs to you... All of this is present and correct.

Nevertheless, it works. And the cast is excellent throughout.

Angus Wright is fascinating as Agamemnon, the King desperately trying to rationalise what the Gods have compelled him to do, to match up the sacrifice he demands of his Army with the sacrifice now expected of him.

And Lia Williams and Jessica Brown Findlay, in their challenging roles of Klytemnestra and Electra respectively, bring complexity and depth to characters that can often become too overworked with hysteria to find sympathetic.

At the climax, it is the story of Orestes that comes to the fore, with Orestes having to answer for the crime he has committed, no matter how just he may have considered his act of revenge. And it's crazy just how this rings true with us even today with the sick perversity of the death penalty still with us, where we punish an individual act of murder with a State-sanctioned one.

It will be interesting to see how audiences react to this show. With a running time of 3h40min, I expect many will be put off, which is a shame as this is a gripping production where you really don't feel the length of that running time.

I applaud the risks taken in this production. Really, you have to. For what is the option? That we leave these tales to gather dust on the shelves? We can't do that. There's too much in them worth examining to just preserve them in their dated and often exhausting traditional productions.

As the cast took their bows, I left the theatre full of questions, the issues raised racing through my head. That's a good sign. That's what we call a result.

Almeida Theatre, London to July 18, 2015

Image credits:

1.Jessica Brown Findlay and Angus Wright in Oresteia. Almeida Theatre. By Manuel Harlan

2.Angus Wright and Lia Williams in Oresteia. Almeida Theatre. By Manuel Harlan

3.Eve Benioff Salama, Lia Williams, Ilan Galkoff & Angus Wright in Oresteia. Almeida Theatre. By Manuel Harlan

Published on June 15, 2015 14:39

June 11, 2015

The Pleasure and Pain of Shoes Examined at V&A

Shoes are a popular subject and it could have been so easy for the V&A to pull together a couple of hundred pairs of shoes, place them prettily and charge an admission fee for still, visitors would have come. So credit to the V&A curation team for deciding to interrogate this subject for the result is a revealing and challenging exhibition on a much-loved item.

Sexuality and shoes have always been deeply intertwined and a part of this exhibition is stylised with sultry red velvet textures and deep maroon colours. It screams seduction. But the pieces on show demonstrate how sex and fetishism have influenced footwear.

The high heels and knee high leather boots are on show, as is the evocative trademark red sole of the Louboutin. But this link with sex is nothing new for also on display is a pair of shoes worn by a Japanese orian, a prostitute, where the platforms are so high as to make any kind of practical movement impossible.

This restriction of female movement retains its power as a source of fantasy, which we see today in all high heels and is demonstrated at its extreme in the David Lynch/Christian Louboutin collaboration that is on show, where the shoes have impossibly angled heels, forcing the woman to crawl rather than walk.

Of course, for many this is in dangerous territory. Shoes which restrict female movement and encourage submission is a politically charged subject. But what was revealing about this exhibition was the history of gender roles and behaviour that has been weaved into shoes - and how this can often surprise.

It is the female shoe that we expect to be high-heeled and embellished. This design is associated with a concept of femininity and, again, the restriction of movement is desirable. In comparison, masculinity is associated with rugged boots and big, heavy shoes.

So where does that leave the cowboy boot? For cowboys are considered to be some kind of masculine archetype but yet the pair of cowboy boots on show are high heeled and decorative, covered in studs and beads. It's interesting, seeing assumptions challenged and this exhibition does just that.

Some of the pairs of shoes are extraordinary historical artefacts - and included with a purpose. One pair of sandals is 2000 years old, from late Pharaonic or early Roman Egypt, and the shoes are delicately embellished with nearly pure gold. Intriguingly their sole is designed with a sharp point at the toes, much like contemporary designs. It's interesting how long this idealized and desired foot shape has been around.

The V&A has vast archives and wonderful access to so many collections to bring together a great range of shoes. And in addition to many historical artefacts there are, of course, some headline grabbers.

David Beckham has lent a pair of boots from his Manchester United playing days and there's the delicate glass slipper designed for Disney's recent Cinderella film - both demonstrations of shoes as fantasy items that can transform behaviour and people. The infamous Vivienne Westwood platforms that Naomi Campbell fell over in are on display (and looking as desirable as ever), as are a pair from Imelda Marcos' vast collection.

But a real highlight is the deadly pair of red ballet shoes from the 1948 film, The Red Shoes. A stunning and iconic treasure from cinema history and in a deeply evocative blood red as opposed to the more usual candy pink.

Much like the stunning Alexander McQueen exhibition that is also on in the V&A, Shoes: Pleasure and Pain examines the extremes in fashion. And much like Savage Beauty, this exhibition is also fascinating - full of craft, intellectual discourse and a flash of celebrity.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London to January 31, 2016

Image Credits:

1.Installation view of Shoes: Pleasure and Pain, Christian Louboutin 'Pigalle' pump © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

2.Installation view of Shoes: Pleasure and Pain © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

3.Installation view of Shoes: Pleasure and Pain © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

4.Red ballet shoes made for Victoria Page (Moira Shearer) in The Red Shoes (1948), silk satin, braid and leather, England, Freed of London (founded in 1929), 1948. Photograph reproduced with the kind permission of Northampton Museums and Art Gallery

Published on June 11, 2015 16:00

June 9, 2015

Theatre Review: Imelda Staunton Stars in a Stunning Revival of Gypsy

Gypsy, the musical based on the life of burlesque striptease artist Gypsy Rose Lee and her mother Rose, is rightly considered one of the greatest musicals of all time. It has it all - a terrific score from Stephen Sondheim and, in Gypsy's mother Rose, one of the most complicated and fascinating characters possible. And this revival at Savoy Theatre, a transfer from Chichester Festival, is one of the finest productions you will ever see of this great show.

Rose (Imelda Staunton) is a driven woman. She wants one thing - unrivalled success and critical acclaim for the apple of her eye, her perfectly blonde, blue-eyed and bubbly daughter June (Gemma Sutton). Rose is adamant June will get the glory and she drags her increasingly resentful daughter across America to perform on every stage possible in her desperate attempts to make this happen.

Everything is sacrificed to this dream, including three marriages and the happiness of her second daughter, Louise (Lara Pulver), who obeys her mother's every wish in the vain hope that one day her mother will love her as much as she loves June.

At the heart of this production is one of the most staggering performances you will probably ever see. If there's a better performance on the London stage right now than Imelda Staunton's, I haven't seen it. And I doubt there is one frankly as Imelda's portrayal of the ultimate show-business mother is flawless.

Every element of her performance is stunning. Imelda seems to grip Rose's complexity with ease. Her motivations remain complex, unclear even to herself, and she can be vulnerable one second, emotionally manipulative the next. And that voice - what a voice!

Imelda is extraordinary, yes, but there are great performances throughout this production. Lara Pulver was, for me, a revelation. Her voice was beautiful, with a wonderful range, and her portrayal of the long-suffering Louise finding the strength to stand up to her tyrannical mother was pitch-perfect. And Peter Davison is the perfect foil for Rose as the faithful Herbie - humbled, overwhelmed and eventually broken.

The wider cast is excellent too, from Gemma Sutton as the mithered and frustrated June, to the chorus and their wide range of parts from showgirls to backing dancers, to the young kids who play Rose's family in their youth.

Direction comes from Jonathan Kent (working again with Imelda Staunton following Good People at Hampstead Theatre and the West End last year) and the pacing is perfect, with inventive stage design from Anthony Ward used to convey the nomadic lives that Rose forces on to her family as she investigates every option, banging on every closed door, to make her daughters famous.

It's hard to go wrong with Sondheim - and all the classics are here from the mighty Everything's Coming Up Roses to the glorious Let Me Entertain You - but these are performed fantastically well and there's so much variety in emotion, in delivery, across the score that you really feel as if you're on a rollercoaster.

You've Got to Get a Gimmick is hilarious, the showgirls mining the humour in that song for all it's worth, whereas Louise's Little Lamb is tender and heart-breaking. And it all builds to Rose's Turn, a tour de force performance where finally, FINALLY, Rose gets the stage to herself.

The tears in the eyes of just about every member of the audience at the end were testament to the emotional power in this production. Rose's final stand, her rage against the dying of the spotlight and the cruelty of show-business, just rocked all of us to the core.

It would be a travesty if Gypsy did not sweep the board come awards season. Tickets are expensive though. Seats at the back of the stalls are £70 and even at that price, my view was restricted by the people in the rows in front of me.

Nevertheless if you can go, I absolutely encourage you to do so as Gypsy may well be the best show in town. Stunning, flawless and it packs an enormous emotional punch.

Savoy Theatre, London to November 28, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Imelda Staunton (Momma Rose) with members of the Gypsy company Photo Johan Persson

2.Imelda Staunton (Momma Rose) in Gypsy Photo Johan Persson

3.Imelda Staunton (Momma Rose) with members of the Gypsy company Photo Johan Persson

4.Lara Pulver (Louise) in Gypsy Photo Johan Persson

Published on June 09, 2015 11:41

June 4, 2015

Review: Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts 'A Riot of Colour'

That great art institution, the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy, is with us once again. All its familiar and much loved hallmarks are there, from the mix of emerging and established artists, to the packed walls and galleries. Only this year it all comes with an explosion of colour.

Michael Craig-Martin is this year's coordinator and he has gone for walls painted in vivid magenta and electric blues. The impact is impressive and gives you a buzz as soon as you enter the galleries but it also makes for an interesting challenge when viewing some of the works.

An example is the muted, almost sombre, Mississippi River Blues by Richard Long, one of the shortlisted works for the Charles Wollaston Award. It's a beautiful piece of titanium white ink pouring down over a black wash. Yet its backdrop of a bright pink wall is such a stark contrast, it can jar a little.

I'm not necessarily criticising the clash - it's actually quite intriguing. But it's quite a conflict between the 'up' and the 'high' that electric pink brings to the mind, and the calm background required for contemplation.

But that's one of the most enduring hallmarks of the Summer Exhibition, the chaos of it. Over 1000 artworks are on display in the galleries, which gives the curators plenty of opportunity to embrace the salon hanging style where the art is crammed together. In no room is this more evident than the Lecture Room, where Bill Woodrow and Alison Wilding have piled in the sculpture. It's a wonderful assault on the senses.

As always, there's great representation from the established artists. There's a vibrant floor-to-ceiling technicolour tapestry from Grayson Perry (who is pretty much a national institution in his own right, these days), drawings from Tracey Emin, a haunting vitrine from Anselm Kiefer (who had his own show at the RA last year) and a stunning acrylic from Anish Kapoor.

A real highlight for me was the wonderful The Sisters, a piece from the late William Bowyer, of two elderly sisters wrapped up in coats and hats sitting inside a cool interior. If I had the £30,000 needed to purchase this going spare, I would buy it. But as an impoverished writer, there is no chance! And certainly my annual dream of purchasing one of the romantic Bill Jacklin scenes remains just that - a dream!

Another highlight was the Small Weston Room. Last year the walls in this room were smothered with small-scale artworks. This year the room has been set aside for works from William Kentridge, the South African artist who has recently been elected an Honorary Academician, and William has chosen an elegant hanging of some of his recent drawings and lithographs.

The works interrogate the recent upheavals in his native country through the use and reassembly of dictionary and encyclopaedia pages into the style of African trees. And the room, with its monochrome palette of black and white, makes for a great contrast with the riot of colour in the other galleries.

For those with a few more pennies than me, there is the opportunity to buy some of the works as the majority of the pieces are for sale and there is a huge range of media to choose from - paintings, prints, sculpture, photography and film.

And of course, architecture too for the Summer Exhibition remains committed to showcasing these works in their dedicated Architecture Gallery. This year the room is curated by Ian Ritchie with a theme of Inventive Landscapes, examining the interdependence of landscape and architecture, and includes works from household names such as Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid and Richard Rogers.

But whether you're buying or not, this year's Summer Exhibition is an exciting, dynamic exhibition, full of craft mixed with a dash of showmanship, and is a terrific showcase for so many talented artists. A great experience. But set aside some time for your visit - there's a lot to see!

Royal Academy of Arts, London to August 16, 2015

Image Credits:

1.View of the Central Hall Photography: John Bodkin, DawkinsColour © Royal Academy of Arts

2.Grayson Perry CBE RA Julie and Rob, 2013 Courtesy the artist, Paragon/Contemporary Editions and Victoria Miro, London

3.View of the Lecture Room Photography: John Bodkin, DawkinsColour © Royal Academy of Arts

4.Royal Academician Conrad Shawcross stands in front of The Dappled Light of the Sun, 2015 (c) Royal Academy of Arts, Benedict Johnson

Published on June 04, 2015 12:15

June 2, 2015

Review: Agnes Martin, Tate Modern 'Serene and Surprising'

This exhibition at the Tate Modern is the first retrospective of Agnes Martin's work in the UK for over 20 years and includes pieces from the full breadth of her career, from her early beginnings in the 1950s to the last piece she created in 2004.

I had expected the show to be very Zen - 11 rooms of huge canvases in muted tones and a cool colour palette. And certainly there's plenty of the spirituality that was such a significant part of Agnes' life evident in her large paintings. Yet there's also an intriguing pursuit of evenness and constancy.

Canadian-born Agnes made her name in the thriving (and male-dominated) New York art scene of the 1960s but she fell out of love with the city, leaving it in 1967 and wandered nomadically across the States and Canada for a couple of years before finally settling in New Mexico, where she stayed until she died in December 2004.

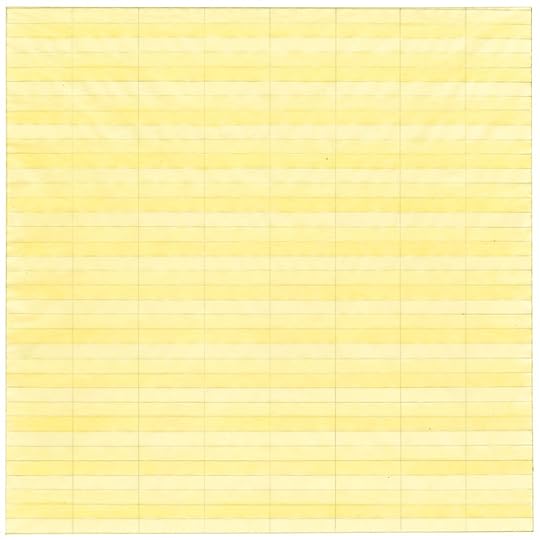

Described as an abstract artist, Agnes' signature style is evident in the large paintings that fill the galleries. From afar, Agnes' pieces impress with their colours, the warm, delicate tones lift you whilst the greys and creams are cool and calm. Yet up close, her canvases and her drawings have a detail that fascinates.

It's when you're up close that you can see a forensic search for conformity across her canvases, the endless repetition of a single shape, whether it's rectangles, grids or parallel lines. Each canvas has these faint, but deliberate, pencil lines or shapes drawn across them - an obsessive pursuit for perfection that could never be satiated.

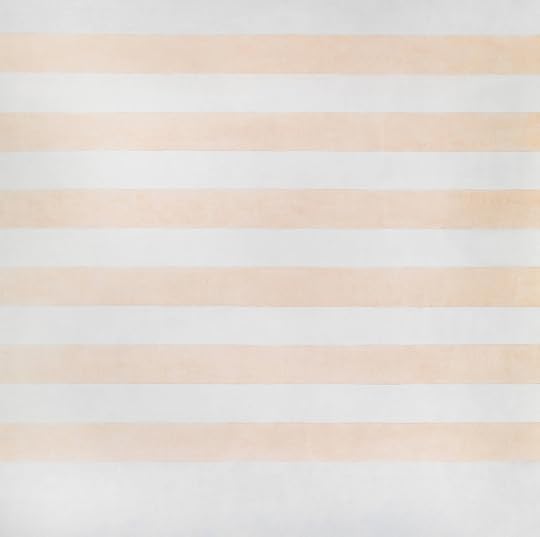

And given how this search sustained her for decades, how it features in almost all of her work, it only emphasises more the subtle changes in colour palette that Agnes Martin would experiment with.

The colours fluctuate from the cold steel greys of A Grey Stone, 1963, Untitled #8, 1989, and the graphite lines in Untitled #10, 1990, to the salmon pinks of Untitled #10, 1975, and the sunny yellows of #Untitled, 1977.

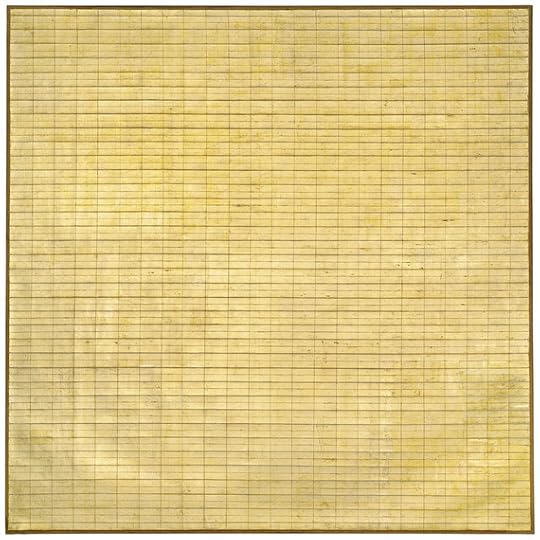

And then there is Friendship, 1963, a shimmering canvas of gold leaf, a beauty placed into sharp contrast by the rigid conformity of the tiny rectangles that comprise it.

And then, in 2004, Agnes returns again to the muted greys and creams in Untitled 2004, an acrylic wash on linen.

Yet even in the works with zero colour - the stark white canvases of The Islands collection, all curated together in a single room - there is fascination. I suspect Agnes wanted these huge white canvases with the faintest of lines on them curated together to enable contemplation. Yet I found these pieces had a real punch to them, a real strength. The sound of white noise.

It's worth noting, at this point, how well this exhibition is curated. The high ceilings and natural light in the Tate Modern galleries provide the ideal setting for Agnes' work. And though the retrospective is shown broadly in chronological order, some decisions have been taken to shift a couple of the pieces around where certain themes, such as the dawn of muted reds and oranges in her work, can be given greater impact when shown together.

I also, particularly, want to take the opportunity to applaud the Tate Modern for their commitment to platforming female artists this year. The Marlene Dumas and Sonia Delaunay exhibitions were both excellent and it is great that they are showcasing the work of another female artist here.

For some, there may not seem much variety in Agnes' paintings. The early rooms include works from the early part of her career when she was investigating and developing her style. And other than the occasional (and surprising) appearance of shapes such as rhombuses and triangles in her later works, much of the work on show follows her reoccurring theme of grids, rectangles and lines in different patterns and hues.

I therefore appreciate that some may find themselves a little jaded with this style by the last room but the juxtaposition between the beauty and order in Agnes' work fascinated me, far more than expected. A serene and surprising exhibition.

Tate Modern, London to October 11, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Agnes Martin, Friendship 1963 Museum of Modern Art, New York © 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

2.Agnes Martin, Untitled 1977 Watercolour and graphite on paper 9 x 9" (22.9 x 22.9 cm) Private collection Photograph courtesy of Pace Gallery © 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

3.Agnes Martin, On a Clear Day 1973 Parasol Press, Ltd.© 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

4.Agnes Martin, Happy Holiday 1999 Tate / National Galleries of Scotland © estate of Agnes Martin

5.Agnes Martin, Untitled #1 2003 Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris © 2015 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Published on June 02, 2015 13:25

May 20, 2015

Review: Chiwetel Ejiofor Stars in Everyman, National Theatre

When people ask me for recommendations on shows to see, I nearly always reply with "well, what do you like?" Because theatre is always horses for courses. Maybe you like Shakespeare, maybe you don't. Maybe you like musicals, maybe you don't. There's something out there for everyone and personal choice, personal preferences, shape everything.

But then occasionally, just occasionally, a show comes along that is so exciting, so dynamic but so profoundly moving that, irrelevant of personal preference, I just say, "Go see this show."

Go see Everyman.

I fear the reputation of theatre as a dry, dusty environment where actors perform in front of a static, traditional set. Not that great productions don't come from such a set-up, but it doesn't attract new blood. And theatre needs new blood. And new blood comes when risks are taken and orthodoxy is challenged.

And this production of Everyman has it all - the piece is electric but hits you like a truck. Whether it's the drug-fuelled raves to a Donna Summer soundtrack, the vivid production design that pulses with energy, or the moments of quiet reflection, Everyman is slick, bold and hangs together beautifully. And at the heart of it all, a stunning performance from Academy Award nominee Chiwetel Ejiofor as Everyman.

The play is an allegory, a lesson to us all. Death has come for Everyman (Chiwetel Ejiofor). Not that he's sick or suffering. This is death out of the blue. A shock. There's going to be no growing old for Everyman, no slow, steady preparation for death. Inside, right here, right now, at the height of his wealth and good health, Everyman is going to have to make his reckoning with God.

Only Everyman is in no place to cut a good impression of himself. He is self-centred, too obsessed with the superficial and in denial about the responsibilities he has in life - responsibilities that can't be passed off with wads of cash, but ones that require love and commitment. So what to do? Well, when Death comes knocking, Everyman starts running.

Everyman trawls through his friends and his estranged family, desperate to find evidence of a meaningful relationship in his life to offer up as proof of a good heart. He delves through his wallet, through his possessions, to find evidence of worth of any kind.

But by the end of this introspection Everyman is going to have to come to terms with what we all will have to do, no matter our loves and wealth, we are all going to have to face Death alone with nothing but our conscience and our soul.

Let's just take a moment here to eulogise over Chiwetel Ejiofor. His stagecraft is awesome. What a cliché this character could have been - an immoral, selfish, drug-addicted banker may not quite be every man but somehow Chiwetel brings out enough humanity and common ground that he really does become Everyman. He is us and we are him.

And Chiwetel gives everything in this role. Everything. His performance is so intense, so committed that the sweat pouring off his brow is practically palpable.

Chiwetel is extraordinary, yes, but he is just one of many successful elements in this production.

Words, or rather the poetry, come from Poet Laureate Carol-Ann Duffy. Startling, funny and heart-breaking, Carol combines romantic verse with popular vernacular with ridiculous ease. So good and fresh is the text that you could easily be forgiven for not realising that Everyman was originally a 15th century play written in Tudor English. Carol has transformed it into something accessible and relevant.

And in this she is helped by an extraordinary thrilling production from Director Rufus Norris and a supporting cast that do it all - sing, dance, perform and move. And it's all so cool. I haven't wanted to be in a cast this bad since American Psycho at the Almeida.

Everyman is such an exciting, emotive production. I was both enthralled and moved. Really, I live for evenings like this, when theatre takes risks, leaps out from the ordinary and delivers that powerful one-two punch of electric dynamism and profound emotional impact.

So, just let me repeat this one more time...

Go see Everyman.

National Theatre, London to August 30, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Amy Griffiths - Goods, Chiwetel Ejiofor - Everyman, Adam Burton - Goods, Clemmie Sveaas - Goods. Photo by Richard Hubert Smith.

2. Penny Layden - Knowledge, Chiwetel Ejiofor - Everyman. Photo by Richard Hubert Smith.

3. A scene from Everyman - centre - Chiwetel Ejiofor - Everyman. Photo by Richard Hubert Smith.

4. Chiwetel Ejiofor - Everyman, Kate Duchêne - God. Photo by Richard Hubert Smith.

Published on May 20, 2015 13:12