Victoria Sadler's Blog, page 6

November 24, 2015

Refugees and Identity the Subjects in Ben Uri Exhibition at Somerset House

Refugees and migration, and integration and identity, are pretty timely subjects given current headlines so it's quite some coincidence that the Ben Uri Gallery is celebrating its centenary with a show at Somerset House, Out of Chaos.

The Ben Uri Gallery is the only specialist art museum in Europe addressing these issues of identity and migration through the visual arts and this show allows them to showcase masterworks from its collection, including pieces from Frank Auerbach, Mark Gertler and Marc Chagall.

Given that Ben Uri holds the most distinguished body of work from artists of European Jewish descent, it's no surprise that the impact of the two world wars and, in particular, the Second, loom large in this exhibition.

Mark Gertler's cubist-inspired watercolour Rabbi and Rabbitzin was painted in 1914 and the tension of impending warfare is caught beautifully in this husband and wife sitting at their simple table but clenched together both in solidarity and fear.

The First World War, of course, had a profound effect on migration of peoples across Europe, many coming to the West and to the UK to escape a destroyed and impoverished Germany, as well as the rise of Communism in Russia and Eastern Europe.

This movement of peoples is shown dramatically in a series of illustrative maps on the walls of the exhibition, but this refugee status, exacerbated even more by the rise of Nazism, had a profound impact on artists and their work.

Included in the exhibition is Josef Herman's Refugees, a painting that was thought lost for 60 years until Ben Uri bought it last year. The painting shows a scared family escaping in the dead of night through silent but hostile streets.

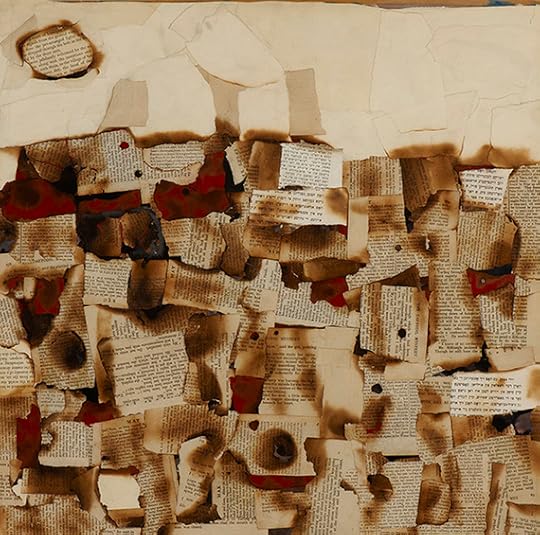

This impact of Nazism and the war is powerfully depicted in the stunning The Ghost Town by Shmuel Dresner - a collage of burnt pages ripped from books that powerfully references the Nazi book burnings.

This exhibition also managed to secure Mark Gertler's iconic Merry-Go-Round on loan from the Tate. The piece's simple lines and dramatic colour scheme only emphasise the screams of the carousel riders as they can never get off the never-ending carousel of conflict, war and pain.

The painting was donated to Ben Uri in 1945 but it was sold to the Tate in 1984 to safeguard the gallery's future so it's great that the loan was secured for this display.

Ben Uri does not stop at the end of the Second World War though. Its collection, and this exhibition, continues to explore the questions of migration and identity right through the post-war years to the present day, and this part of the exhibition has some absolute gems in it.

An eye-catching piece is Eva Frankfurter's West Indian Waitresses, a tender and quite wonderful reflection of British multiculturalism.

And the exhibition comes right up to date with modern media including photography from Sophie Robertson and the bright Mornington Crescent, Summer Morning II from Frank Auerbach.

The exhibition also includes a film about Ben Uri and it's clear that the current focus of the gallery is to find a permanent home in central London. Currently a location is elusive so do take this opportunity to see Out of Chaos at Somerset House as it's a great exhibition that shines a light on such an important, timely and pertinent subject, and the scope of works that have been collated together to showcase the Ben Uri Gallery is unquestionably impressive.

And all this without an admission fee? That's got to be applauded.

Inigo Rooms, Somerset House, London to December 13, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Mark Gertler, Rabbi and Rabbitzin, 1914, watercolour and pencil on paper, 82.5 x 71 cm, Ben Uri Collection

2.Shmuel Dresner, The Ghost Town, 1982, Collage on paper, 78.5 x 78.5 cm, Ben Uri Collection © The Artist

3.Josef Herman Refugees, Gouache on paper, 60.7 x 53.2 x 3.3 cm, Ben Uri Collection © Estate of Josef Herman. All rights reserved.

4.Frank Auerbach, Mornington Crescent, Summer Morning II, 2004, Oil on board, 69 x 69 cm, Ben Uri Collection. © The Artist

Published on November 24, 2015 11:31

November 18, 2015

Review: Brilliance in Pastels from Jean-Etienne Liotard, Royal Academy of Arts

Pastels are a nightmare to work with, and they provide a real challenge for artists who want to add delicate details and tones. So how wonderful it is that the Royal Academy has chosen to put on a show on Jean-Etienne Liotard so that more can marvel at how this artist mastered this tricky medium.

Liotard was one of the most highly accomplished portraitists of 18th century Enlightenment Europe, crossing the continent back and forth to complete commissions on royalty and high society (in fact, Liotard was so respected that the rich would often travel to him to ensure he could complete their portrait).

That he chose to work so much in pastels rather than the more conventional oils is impressive enough but what also impresses in this small but impressive survey of his work in the Sackler Wing is just how far preservation techniques have come as you'd expect these 300 year old pastel portraits to have faded, crumbled into dust. Not at all. Their colours and lines are so sharp, so fresh, as if they had just been completed. Extraordinary.

Such preservation ensures we can see these works as they would have been completed so we too can admire the details and the expressions that Liotard was able to fashion.

The skin tones are sublime - creamy and blushing for the healthy, such as in the stunning portrait of Julie de Thellusson-Ployard, but also sweaty and sickly for the ill, such as in the tender portrait of Princess Louisa Anne.

And the intricacy of fabrics and dress is so impressive. From the sheen on luxurious satin bodices to the crumples in a cotton apron, the pastels are worked in such a way that you can almost feel the fabric underneath your own fingertips.

But this impressive ability to capture even the most delicate of details isn't just reserved for his portraits. Included in the exhibition are examples of Liotard's still-life works and his genre scenes of more ordinary lives. Take a good look at these. The shine on the apples in the fruit bowls, the furry skins of the peaches... They are quite extraordinary. Getting texture this fine in more routine mediums is a challenge, let alone in pastels.

But there is more to this exhibition than just worthy admiration of the pastels. There are some of Liotard's oils too, including my favourite of his - Woman on a Sofa Reading. And one of the themes in this work, which you then see in so many others, is Liotard's fascination with the culture and fashion of the Turkish Empire.

Liotard lived in Constantinople for four years and this immersion in Turkish society started almost a form of branding for Liotard where he brought in Turkish customs and dress into his works, giving them a unique perspective, a variety, that none others had.

Though Jean-Etienne Liotard had a considerable reputation in his lifetime, that's not the case now. His achievements overlooked as new artists and Masters came on to the scene..

There is, though, a vast pool of potential visitors in the numbers who are visiting the RA to see the Ai Weiwei exhibition downstairs. I hope they take the opportunity to visit this Liotard show too as there is much to admire in this fascinating display of works from a master craftsman.

Royal Academy of Arts, London to January 31, 2016

Image Credits:

1.Jean-Etienne Liotard, Julie de Thellusson-Ployard, 1760, Pastel on vellum, 70 x 58 cm. Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur, inv. 278. Rodolphe Dunki, Geneva; acquired 1935. Photo SIK-ISEA. Photography: Philipp Hitz

2.Jean-Etienne Liotard, Archduchess Marie-Antoinette of Austria, 1762. Black and red chalk, graphite pencil, watercolour and watercolour glaze on paper, heightened with colour on the verso, 31.1 x 24.9 cm. Cabinet d'arts graphiques des Musees d'art et d'histoire, Geneva. On permanent loan from the Gottfried Keller Foundation, inv. 1947-0042. Photo Musee d'art et d'histoire, Geneva. Photography: Bettina Jacot-Descombes

3.Jean-Etienne Liotard, Woman on a Sofa Reading, 1748â??52. Oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Photo Gabinetto Fotografico dell'Ex Soprintendenza Speciale per il Patrimonio Storico, Artistico ed Etnoantropologico e per il Polo Museale della città di Firenze.

Published on November 18, 2015 11:11

November 11, 2015

Frank Auerbach at Tate Britain: Unique and Emotional

Not every art show overwhelms you. Certainly not every artist has the ability to capture intense, strong emotions on a canvas, let alone harness them in a way that grabs the viewer. But Frank Auerbach is different. And this show of Frank's work at the Tate Britain is different, for what it displays is not just an artist of profound talent and ability, but also one of immense emotional intensity and depth.

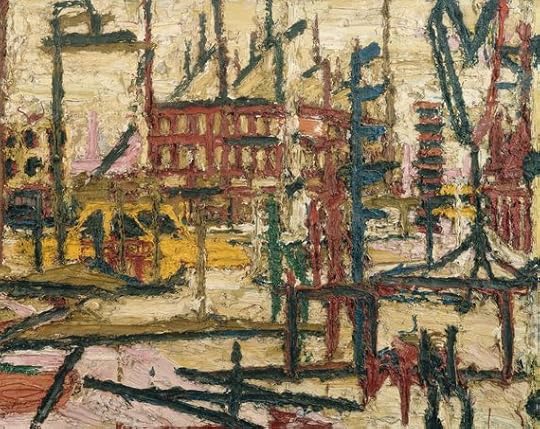

What first hits you about Frank's paintings is the texture. These are canvases thick with oils. Layers of paint built up and scraped down, the artist always editing and correcting himself, painting over what he saw a moment ago with what he sees now. And doing this hundreds of times.

This is particularly true in the first few rooms - the exhibition is hung in broadly chronological order - where Frank's earlier works are canvases almost two inches thick with oils that have been scraped aside, built up and painted over.

Canvases were too expensive to go to waste back then but in addition to the hazy blurred figures and landscapes created, this dense build-up of oils betrays Frank's own battles to channel how he feels about the world around him, about the figures and places in front of him, and to convey them in all their complexity.

The results are paintings so thick with oils that they are almost three-dimensional, the forms rising out from the canvas. And the forms themselves, such as in E.O.W. Nude, 1953-4, are blurred, their skin cracked from the layers of old paint, their outline unclear yet oddly sharpened by reducing form to colour.

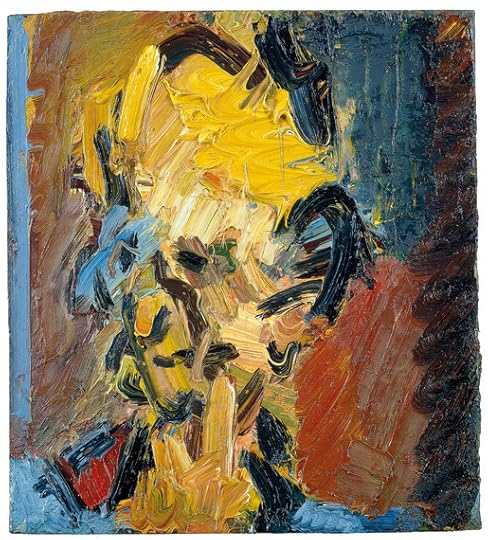

Then what hits you next is the emotional depth. These are profound, emotionally charged pieces of work. There is a darkness in Frank's paintings of people that reveals as much about the artist as they do about the sitter.

It doesn't seem appropriate to call these works 'portraits' for these are more psychological interrogations rather than reflections of people's external appearance. These are examinations of the human condition, of our shadows and thoughts.

The oils are worked so heavily that much is obscured, facial features blurred and undefined. Whether it's Head of E.O.W II from 1961 or Head of William Feaver in 2003, the intensity, the fevered reworking of the pieces, is practically tangible across the body of his work.

And even when he uses uplifting or mellow colours, there's still an eeriness, such as in Head of E.O.W II where the warm yellow tones of the skin are cut through by the fiercest set of beady red eyes you've seen. Or in E.O.W. Half-Length Nude, 1963, where the sitter's soft skin tones are contrasted with the shadow of red that falls across her face.

I was completely hooked by the series of paintings of favoured model, Juliet Yardley Mills seated in his studio. And again here, the vivid yellows of the face and torso are hemmed in by darkness, by thick black outlines to her frame, her features carved in using thick black paint. And like so many, the sitter is introspective, her gaze looking away into the distance, her attention not on us but elsewhere.

Frank can turn away from these brighter hues and, when he does, the intensity is unrestrained. The stunning and haunting Head of J.Y.M II, 1984-5, is a case in point. A deathly pale face and neck cranes back from us, desperately avoiding our gaze and attention. The sombre palette of greys and blacks only heightening the sense of someone desperately lost to the tumult of their own mind.

Or should that be the artist's weaving in how he feels, as well as the sitter? Who knows? But what you sense from these portraits is, unequivocally, life - for both artist and sitter. There is blood in these people's veins. Passions and fears, hopes and dreams.

So the contrast with the energy in Frank's landscapes and urban settings is not just marked, but extraordinary.

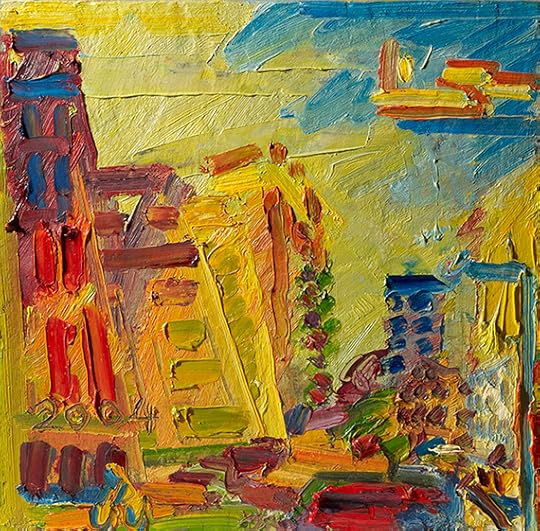

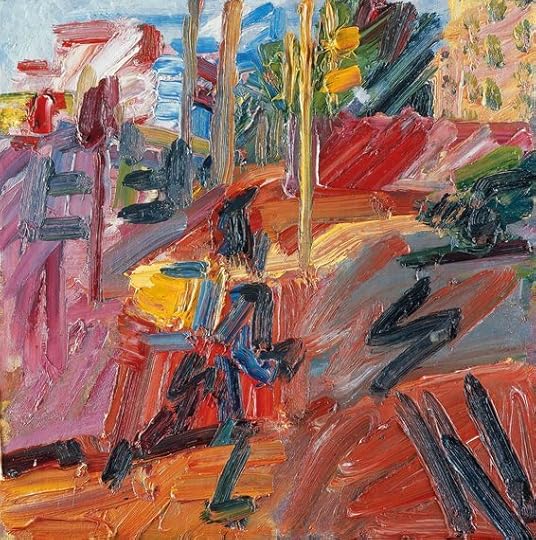

Frank has spent most of his life living and working in North London and he has repeatedly returned to the area around him - to Mornington Crescent, to Primrose Hill - and his works offer fascinating insight into how these places have developed and transformed over the past 50 years.

These canvases brim with energy, with motion. Rapid broad brush strokes in reds, pinks and oranges, the blurring of traffic and people as they almost pass through the painting. It's like a snapshot of frenetic energy, life with the pedal to the floor, everything in a rush.

Yet there is rigid structure too. Slick, bold, straight lines define the buildings, the pavement, even the lampposts. There is architecture and order to these compositions. Order containing (just about) the chaos that happens within.

Sometimes I do understand when people come out from art galleries and say, 'you know it's fine but I didn't really get it' or 'it's fine but I'm not really moved'. It happens, I get that. And contemporary art especially can seem emotionally inaccessible for many. But I swear you won't feel that with this extraordinary Frank Auerbach retrospective. It's brings both an emotional rush and intense emotional reflection. A unique exhibition on a unique artist.

Tate Britain, London to March 13, 2016

Image Credits:

1. Hampstead Road, High Summer 2010, Painting, Oil paint on board 562 x 562 mm, Private collection © Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

2. Head of J.Y.M II 1984-85, Private collection © Frank Auerbach

3. Head of William Feaver, 2003, Oil on board 451 x 406 mm, Collection of Gina and Stuart Peterson © Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

4. Mornington Crescent 1965, Painting, Oil paint on board 1016 x 1270 mm, Private collection © Frank Auerbach, courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

Published on November 11, 2015 02:06

November 4, 2015

Belarus Free Theatre: 10 Years of Theatre and Oppression

Art matters. And it's hard to think of a theatre company that has proved that more than Belarus Free Theatre (BFT). Now about to celebrate their tenth anniversary, BFT has persisted against the most extraordinary odds to not just confront oppression, but to create challenging and vital theatre.

Belarus Free Theatre was created as a response to the crushing of creative freedoms by dictator-President Lukashenko. Sadly Lukashenko is still with us - but so is BFT. So, ahead of their anniversary festival, Staging a Revolution, I set down with founding member Natalia Kaliada.

"We wanted to talk about subjects that are taboos in Belarus," Natalia explained, on how BFT got started. "Gay rights, depression, suicide... These are all taboo. They don't exist in Belarus. People are always told, these things don't happen. But of course they do."

It is no surprise that freedom of speech evaporates in dictatorships, but I was curious as to what made theatre generally, and BFT specifically, such an effective and formidable form of protest. "Artists are like scanners" Natalia explains. "They scan society quicker than journalists and politicians. Artists are sensitive to predicting what happens to societies."

And certainly BFT productions have been very sensitive to themes in society, such as Minsk, 2011 on sexuality and 4.48 Psychosis on mental illness in young people. As Natalia explains, "we always ask ourselves, what is the call to action that will empower all of us and live in every single show?"

BFT is theatre on the front foot - never shying away, never pulling punches. But these are also shows with human stories at their heart, their emotional punch as profound as their political one. But they are not the only Belarusian artists currently in the spotlight. Earlier this year, writer Svetlana Alexievich won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Yet she too is not exempt from censorship. "None of her work is part of the curriculum in Belarus" Natalia adds.

With such censorship, raising finance for their shows remains nigh-on impossible for BFT. Possible domestic supporters run the risk of being blacklisted.

"We will have meeting with them (the possible patrons)" Natalia explains. "These will go well and they will say, I will see what I can do. But when we call them back at their offices, they call their staff into their office and put the call on speakerphone and then tell us they won't be supporting us. So they have witnesses. So when the KGB calls, these people have staff who can say, yes, he turned the Belarus Free Theatre down. The Soviet Union is still with us; it's just shifted shape."

And it's not just financial patrons who are in danger. Supporters of BFT live in fear for their lives - many have been kidnapped and killed. But the aim remains to get the message out as wide as possible. "To do this," Natalia says "our shows are free in Belarus. We do not charge people to see our shows."

Enticement, yes, but balance that with the fact that just attending a show in Belarus is riddled with danger. Venues are never revealed in advance. Instead, audiences give their phone numbers to certain contacts and then, on the day of the show, they are told where to meet to see the performance.

Natalia adds, rather matter-of-factly "Our audiences must always take their passports, just in case of a raid." A sobering reminder that what is an evening's entertainment in the UK is a political act in Belarus.

Staging a Revolution will include recreation of these underground shows, as well as a more orthodox string of shows at the Young Vic. For the underground shows, the London audience will have their name down on a list and on the day of the show, they'll be contacted to confirm where the show will be performed.

But London isn't Belarus and Natalia acknowledges this difference. "You cannot recreate that tension, that fear, that the show will be raided."

It would be a mistake though to think there's nothing we can learn from BFT. Not only does their subject matter resonate but also there is a lesson on self-censorship. "We always believe it can't happen to us" Natalia adds. And indeed she is right, as the recent cancellation of the NYT play, Homegrown, on radicalisation proves.

It is therefore no surprise that BFT has a significant and loyal following, including stars such as Kevin Spacey, Tom Stoppard and Ai Weiwei.

"This is crucial for the people in Belarus in that they do not feel abandoned or forgotten" Natalia explains, but she is adamant that the non-celebrities are just as important. Referring to the BFT's current Twitter campaign, #ImWithTheBanned, Natalia added "If an artist is prohibited, it is an urgency for us to stand up and say, I'm with the Banned."

But BFT is always looking forward. I asked Natalia what she was off to do next. I meant it more in the, which mountain are you off to climb next kind of way yet her answer revealed how important grassroots theatre remains to her.

"I'm doing a theatre class on Skype" she said. "A class in Belarus on small scale art projects, on disability." Adding wryly, "we don't have disabled people in Belarus, you see. Just like we don't have dissidents, gay people or Nobel Prize winners for literature. They are invisible. They don't exist."

Image Credits:

1.Belarus Free Theatre perform Minsk 2011 © Nikolai Khalezin

2.Natalia Kaliada co-founder of Belarus Free Theatre

3.Belarus Free Theatre perform Trash Cuisine. Photo by Simon Annand

4.Belarus Free Theatre perform Trash Cuisine. Photo credit Simon Annand

Published on November 04, 2015 10:27

October 27, 2015

Review: Jane Eyre, National Theatre 'Less Would Have Been More'

This adaptation of the much-loved book, Jane Eyre, is a really ambitious attempt to translate the entire novel into a dynamic, energetic production. The result is a whistle-stop trip through the story that touches on every single event in the book, but doesn't always capture the emotion.

Added to that, director Sally Cookson employs so, so many tricks and devices in the production that you feel a bit overwhelmed, a bit numb, and the heart of the story gets left behind.

Not that you don't know the story already.

Charlotte Bronte's tale of an orphan who battles extraordinary cruelty and injustice throughout her life, yet shows indomitable courage to shape for herself a life of love and compassion, is a classic. However stage adaptations require a choice to be made - what should be kept and what should be left behind?

The issue is almost nothing is left behind. It's all here - Jane's birth, the death of her parents, death of her uncle, the cruelty of her Aunt, her friendship with Bessie, being carted off to Lowood Institution, her friendship with Helen, Helen's death, becoming a teacher, advertising as a governess, going to Thornfield Hall, meeting Rochester.... And all that is before the interval. I was exhausted.

But the profound impact of covering all of this ground is that you're not emotionally grabbed. I just wanted to halt the production and just go, 'stop, stop! Please, someone have a conversation with Jane for more than a minute.'

I was just longing for some emotional attachment and the speed in the production, its energy, is actually a real barrier to that.

To compensate, director Sally Cookson invests in an impressive production design. The Lyttleton is stripped bare and the play is staged on a two storey wooden platform, utilising a versatile company and many theatrical devices to turn this into a multi-functional space and an exciting piece of theatre.

There's music and physical movement, on-stage costume changes and clever use of lighting and props. The company work their socks off playing the myriad of characters in Jane's life, and the ghostly noises from the attic are atmospheric and intriguing.

But often these tricks and devices were used again and again. And again. Such as Rochester's beloved dog, played superbly by Craig Edwards. When Craig first morphs into the dog, it's funny, unexpected and his replication of dog behaviour is extraordinary. But when it happens for the fifth, sixth, seventh, even eighth time, well, it's overdone. And distracting. You end up watching the dog and not the drama.

Similarly for the running. Endless running. Whenever Jane was on the move, the company would come together into the centre of the stage and, focus forward, run together in unison. The first time it happens, you think, wow. But second, third, fourth time... Yes, you get the picture.

One that is effectively used is the subtle use of the company as a chorus, verbalising the internal conflict in Jane's head. Credit to dramaturg Mike Akers for pulling that out of the book and on to the stage. A wise and clever choice over the more obvious soliloquy.

There is no doubt that the staging is impressive but there's the sense that director Sally Cookson has pulled all the tricks out of her bag. No need. Keep some in the bag. It's evident that she is a real talent with great vision. She didn't need to overplay her hand.

Having said that, perhaps the Lyttleton, with its traditional proscenium arch layout, was not best suited for this production. The Dorfman would have been far more appropriate. The set design from Michael Vale would shine in the round and it's a shame it's not given that opportunity here.

The acting though is impressive from all. Madeleine Worrall gives a spirited performance as our heroine, always challenged by what life throws at her but never broken. And she works hard, never leaving the stage. And Felix Hayes is a commanding, tormented Rochester.

Yet when their dramatic reconciliation comes, it doesn't hit hard. It's then that you realise that too often this production plays the head and not the heart, which is a shame. There is the essence of a really interesting production here but just too many ingredients. Less would have been so much more.

National Theatre, London to January 10, 2016

Image Credits:

1.Madeleine Worrall (Jane), Jane Eyre at National Theatre. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

2.(From l to r) Maggie Tagney, Felix Hayes, Laura Elphinstone, Madeleine Worrall, Simone Saunders and Craig Edwards. Jane Eyre at National Theatre. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

3.The company of Jane Eyre. Jane Eyre at National Theatre. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

4.Felix Hayes (Rochester) and Madeleine Worrall (Jane). Jane Eyre at National Theatre. Photo credit: Manuel Harlan.

Published on October 27, 2015 11:59

October 22, 2015

New Exhibition on Julia Margaret Cameron - A Photography Pioneer

Julia Margaret Cameron is an inspiring figure. This is a woman who picked up a camera for the first time when she was 48 years old and yet, in her short 15 year career, became a pioneer in photography.

History is littered with women whose extraordinary achievements are overlooked or watered down. Even omitted completely. So it's wonderful that the Science Museum has decided to use the bicentennial of Julia Margaret's birth to create an expansive display of her work to not just commemorate but also to increase awareness of one of the most influential figures in the history of photography.

Born in Calcutta in 1815, Julia Margaret worked for most of her photographic career from her house on the Isle of Wight, Dimbola Lodge. However she moved to Sri Lanka in 1875, when her husband's income from plantations started to fall, yet she continued her work there (though with reduced frequency) until she died in 1879.

Broadly, her work can be compartmentalised into three broad categories: her naturalistic and striking portraits of friends and family, her intriguing staged shots that evoke religious and dramatic texts, and (my personal favourites) her breakthrough work on local communities in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

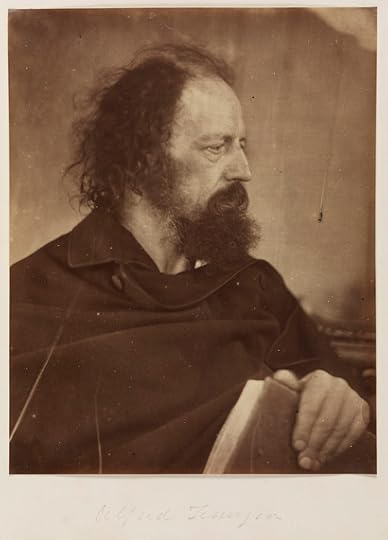

There are many of her distinctive portraits on show. Her photographs of Alfred Tennyson very much defined the familiar image we have of him. She also photographed other respected people in her social circle, including the Irish poet Aubrey de Vere and Robert Browning.

But Julia Margaret often drew on dramatic texts and religious narratives to create staged tableaux. A great catalogue of these fascinating images are on show, many of her longtime maid, Mary Ann Hillier, who was often roped in and made to dress as the Virgin Mary.

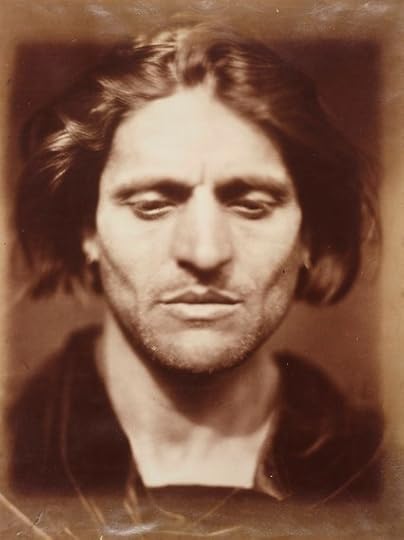

And as well as iconic religious imagery, Julia Margaret also created visual representations of texts including Romeo and Juliet and The May Queen, and included in this display is the only existing print of her iconic image of an unnamed Italian actor as Iago from Othello

But it's her stunning work from her time in Ceylon that grabbed me most. Her portraits of workers and local residents were unusual in that they were naturalistically observed pictures of individuals, photos that brought to life people and personalities, rather than the more common group images at the time that just depicted non-British people ethnographically, as a singular mass of faces rather than as individuals.

But common across the photographs is evidence of Julia Margaret's unique and trademark style. She loved soft focusing backgrounds in her images, which only emphasised more those parts of the image that she put into sharp focus. A great example of this is her arresting photo The Mountain Nymph, where the face is so sharp and clear, it seems to thrust out of the photo straight out at you.

Julia Margaret also liked scarring her images and embraced technical faults, even bringing them in deliberately, to add artistic expression to her photographs. This unconventional approach infuriated many critics at the time who looked to photography to generate clear, precise 'perfect' images.

But of course it's the individuals and the risk-takers who leave a legacy. Julia Margaret's insistence in sticking with her approach, in spite of the criticism, created her reputation as a pioneer and amongst the first to blend art with photography.

In fact, when a collection of work, known as the Herschel album, was sold to a private collector at Sotheby's in 1975, the transfer was blocked by the UK government and the action marked the first time that photography in Britain was officially classified as works of art.

It's also worth noting that, such was the impact of Julia Margaret Cameron on photography, that this is the not the only exhibition planned to mark her bicentennial. Over the road, the V&A will be opening their own show on Julia Margaret's work at the end of November. That exhibition, like this one, will rightly increase understanding about this brilliant and pivotal figure.

Science Museum, London to March 28, 2016

Admission Free

Image Credits:

1.The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty, June 1866, Julia Margaret Cameron © National Media Museum, Bradford / Science & Society Picture Library

2.Alfred Tennyson with Book, May 1865, Julia Margaret Cameron © National Media Museum, Bradford / Science & Society Picture Library

3.Iago, Study from an Italian, 1867, Julia Margaret Cameron © National Media Museum, Bradford / Science & Society Picture Library

4.Young Ceylonese woman plantation worker, c.1875-1878, Julia Margaret Cameron © National Media Museum, Bradford / Science & Society Picture Library

5.Installation Shot - Influence and Intimacy at Media Space, London

Published on October 22, 2015 02:08

October 14, 2015

Damien Hirst Opens a New Art Gallery in London

London has a new art gallery. And this one comes from the pockets - and the collection - of Damien Hirst. Newport Street Gallery is the result of Damien's efforts and commitment to put the 3,000 pieces of art in his personal collection on public display so that as many people as possible can see them.

As Damien said on the opening of the gallery last week, "I've felt guilty owning work that is stored away in boxes where no-one can see it. Having a space where I can put on shows from the collection is a dream come true."

And kicking off the exhibitions in his new gallery is one on John Hoyland, one of Britain's leading abstract painters (though he hated that term, preferring to emphasise the instinctiveness of his process). And Power Stations, which is what the exhibition is called, presents over 30 of John's large and brightly coloured abstract paintings, hung broadly in chronological order.

The paintings are huge - literally and metaphorically. The canvases are vast and there's a terrific dynamic energy barely contained within them. Bold colourful strokes, splatters of paint, thick chunks of oils scraped across the canvas with a palette knife... Yet the works are powerfully emotive too.

The exhibition starts with a room filled with warm, sensual red and maroon canvases, some of which have a smattering of spherical shapes within them, others more rigid lines and rectangles.

This then gives way to a passage of work with far more rigid definitions in more stark colours - grey cubes, orange rhombuses and a quite nihilistic red square on a vast black canvas.

There's a fascinating break from this bold palette in the early 1970s when the reds and blacks are replaced with pinks and creams. And instead of the sharp lines and squares, there are softer, more fluid shapes. Lines seem more porous and suddenly the art goes from angry, confused and tense, to romantic and warm.

And then just as quickly, this sentiment evaporates. Yet a marked change remains.

The reds and blacks return, but this time accompanied with deep blues. And though distinctive lines and shapes re-emerge, their form is not as sharp and precise as before. They're softer, more reflective.

The show is a wonderful testament to John Hoyland's much underrated output and it benefits from being in great surroundings.

There is a terrific openness and democracy to the Gallery - not only is admission free but there are no lines or ropes around the paintings, and you don't ever feel as if you're being scrutinised by over-attentive security.

Interestingly there is no accompanying text for the art either - though whether that will continue, who knows. But it does allow the art to speak for itself, without being framed or interpreted by others - instead allowing visitors to interpret it as they see fit.

The galleries are huge, giving visitors plenty of space and opportunity to both get up close and stand back from the art, to see it from various perspectives. The whitewashed walls may be featureless (and pretty standard for a gallery) but given the riot of colour and emotions in the canvases, a simple background is appropriate here. Who's to say they won't change for other shows?

The gallery itself, which is in Vauxhall, spans five buildings, part of which was initially used by Damien as a studio space. The redevelopment of the site took three years (and a lot of money) but it has been well worth it.

On the opening of the gallery, Damien said that "Newport Street is an incredible space with an amazing sense of history" and that is true as three of the converted buildings were listed Victoria buildings that were purpose-built back in 1913 to serve as scenery painting studios for theatres in the West-End.

There is something romantic and just about that purpose and history not being lost, that art will continue to have a place in these streets. Future exhibitions, though unannounced, will vary between solo and group shows. And given that Damien Hirst is both a prolific collector of art and a damn fine curator (whatever you think about his dead sheep), expect the Newport Street Gallery to put on some must-see exhibitions. Including this one.

John Hoyland: Power Stations showing at Newport Street Gallery, London to April 3, 2016

Image Credits:

1.Gallery 1 -® Victor Mara Ltd, Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates

2.Gallery 4 -® Victor Mara Ltd, Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates

3.Gallery 5 into 6 -® Victor Mara Ltd, Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates

4.Gallery 6 -® Victor Mara Ltd, Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates

Published on October 14, 2015 11:32

October 10, 2015

Review: The Father, Wyndham's Theatre 'Astonishing and Heartbreaking'

The Father may well be one of the most emotionally devastating pieces of theatre I have ever seen. A play about dementia and its toll on those with it, and those who love them, is never going to be the most joyous of subjects but this production takes your heart into its hands - and then breaks it.

The writing here, oh, it's just so clever. The world as Andre (Kenneth Cranham) sees it is played out in front of us. But his memory, his version of events, can't be trusted. His mind is shattered, fragmented, with the scenes constantly repeating or starting again. The piece at first seems deliberately confused and obscure - one moment his daughter, Anne (Claire Skinner), is happily married and living in Paris, the next she's a long-term singleton on her way to London.

The confusion is cleverly exacerbated by having a number of actors play the same characters - then switching the actors around. Like Andre, we recognise the faces but thought they were someone else. And that switching of actors keeps going throughout, always just preventing you from getting a firm grip, always keeping you insecure and unsure about what is real, and what is just a figment of Andre's confused mind.

But through all this, there is a thread to be followed. Andre is not well. He is getting worse and the pressure on his daughter is just too much. And as it becomes clear that even a carer at home isn't enough, Anne faces the terrible decision of whether to put her father into a home with round-the-clock care.

The pain is so distressing. For all of Anne's sacrifice, Andre can be so cruel. Yet his frustration - his panic and anger - as his world spirals out of his control is practically palpable. By the end I had my head in my hands, I was so distraught.

And there is a darkness to this play beyond the heartbreak that keeps you intrigued, whether it's the constant references to a missing daughter or the terrible shadow of patient abuse.

Each actor in this play is superb, effortlessly putting down and picking up whichever character they're playing in that scene, but there's no doubt about the star performance. Kenneth Cranham takes your breath away as the man whose disintegrating mind is falling away from him like leaves from a tree.

And sadly I can't take credit for that elegant turn of phrase as that's taken straight from Christopher Hampton's beautiful translation of Florian Zeller's moving play that blends drama with emotional heartbreak.

Credit also goes to director James Macdonald for letting the story lead yet packaging it up with a clever use of actors and a deceptively simple set from Miriam Buether that, piece by piece, falls away as Andre's mind unravels.

There just is no flaw or fault in this play at all. And its emotional impact is profound. Hard to watch but impossible to look away,The Father may well be the best new play of the year. Astonishing and heartbreaking.

Wyndham's Theatre, London to November 21, 2015

Image Credits:

1.The Father - Kenneth Cranham - Photo credit Simon Annand

2.The Father - Claire Skinner - Photo credit Simon Annand

3.The Father - Kenneth Cranham, Claire Skinner - Photo credit Simon Annand

Published on October 10, 2015 07:26

October 7, 2015

Review: Goya the Portraits, National Gallery 'Dazzling Brilliance'

Incredibly, the new Goya exhibition at the National Gallery is the first ever to focus solely on this great man's work as a portraitist. About 150 of Goya's portraits survive today and half of these have been curated together into this unprecedented exhibition that includes work from across his career - from his early days in the court of Madrid, to dramatic works completed in his last years in self-imposed exile in France.

There is such talent, such genius in Goya's work that it's hard to know where to begin. His technical excellence is just ridiculous - the skin tone, glimpses of veins in ageing hands, the delicacy of the mantilla lace, the shimmering texture of the satin dresses, the flash of colour from sashes and hat linings, the bold, bare backgrounds...

But more than this, beyond his technical brilliance, Goya captured the inner spirit of his sitters. He brought out their personalities, their character. This ability to humanise the even the most regal of sitters, to bring informality to such formal arrangements, is the hallmark of Goya.

The 70 portraits on show demonstrate Goya's genius beautifully and include works that have never been exhibited publicly before, having remained in the possession of descendants of the sitters, and some that are rarely lent. This includes the impressive Duchess of Alba, 1797, which has only once left the United States, and has never before travelled to Britain, and the delicate and intriguing portrait of Don Valentin Bellvis de Moncada de Pizarro, 1795, which is on public display here for the first time ever.

The exhibition is hung in chronological order and, interestingly, with no explanatory text printed on the wall in each room to give an overview of the paintings. Not that much explanation is needed. But it allows us to observe how Goya's skills and style developed over time.

In the earlier works, such as Maria Teresa de Vallabriga y Rozas on Horseback, 1783, and Don Luis Maria de Borbon y de Vallabriga, 1783, there is still an air of formality about the pose, sitters are beady-eyed, and their mood and personality not always easy to read.

Yet as the exhibition progresses, you can see the development of Goya's talent and the evolution of his signature style.

The Dowager Marchioness of Villafranca, 1796, on loan from the Prado, is a beautiful painting that depicts this elderly woman in her finest dress, yet blends that with the quiet contemplation of her pose and the warmth in her eyes that glance up towards us. There is such tenderness in this portrait, which has been painted with such compassion and humanity.

At the other end of the spectrum is the glorious portrait of the French ambassador Ferdinand Guillemardet, 1798. This handsome man is in all the required finery, his sword tied to his waist by a scarf in the bright colours of the new French republic, yet he is reclining in a chair with all the ease of a man who is amongst friends.

And then there is the astonishing portrait of Charles III, Charles III in Hunting Dress, 1786-1788. Gone is the usual depiction of royalty with stiff straight backs and flawless handsome features. Instead this king, well, it's not flattering to put it kindly. This is very much a king who wants to be seen as a 'man of the people' and Goya has captured an approachable demeanour to his face - a kindly father figure rather than a king to be feared.

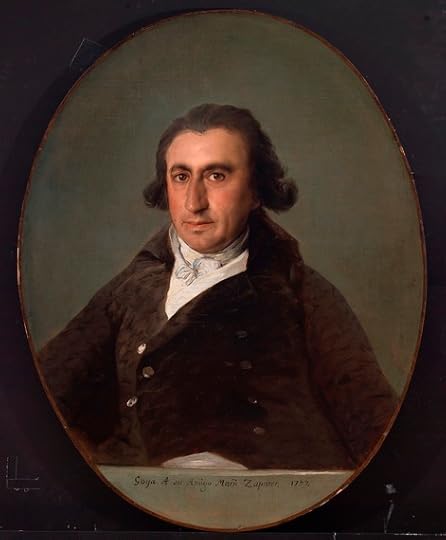

Goya's reputation was made in his work on the Spanish aristocracy and though these are impressive and brilliant, it is the room dedicated to portraits he made of his close friends that, for me, dazzles most of all. The depth of his affection for them is evident and the results are a series of sensitive portraits that just brim with intimacy and warmth, whether it's the elusive mood of the actress Antonia Zarate, about 1805, or the fullness under the chin in the portrait of his best friend, Martin Zapater, 1797.

Goya's dazzling brilliance is beyond doubt and this exhibition offers a unique, maybe once in a lifetime opportunity, to witness some of this master's finest work up close. Take this opportunity.

National Gallery, London to January 10, 2016

Image Credits:

1.Francisco de Goya, The Duchess of Alba, 1797, Oil on canvas 210.1 × 149.2 cm. On loan from The Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY © Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York

2.Francisco de Goya, Don Valentín Bellvís de Moncada y Pizarro, around 1795 Oil on canvas 115 x 83 cm. Fondo Cultural Villar Mir, Madrid © Fondo Cultural Villar Mir, Madrid

3.Charles III in Hunting Dress, Francisco de Goya, 1786-84. Oil on canvas 210 x 127 cm © Photo courtesy of the owner.

4.Francisco de Goya, Martín Zapater, 1797 Oil on canvas 83 x 65 cm Bilbao Fine Arts Museum © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao

Published on October 07, 2015 11:39

October 3, 2015

Review: Medea, Almeida Theatre - Fresh, Modern but Something Lost

I love Medea. For me, the horror in this story is when you feel her terrible act was not just inevitable but understandable. Even logical. Yet that descent, that terrifying unravelling, is missing in this new production at the Almeida Theatre.

As you'd expect from the Almeida, everything has been shaken up. This Greek tragedy has been revolutionised. Director Rupert Goold and writer Rachel Cusk have thrown out the sandals, the robes and the Argonauts and replaced them with a contemporary setting - a modern Medea for a modern world.

Medea (Kate Fleetwood) is battling to keep her kids away from the TV whilst screaming at her soon-to-be-ex-husband Jason (Justin Salinger) down the phone, Creon (Andy de la Tour) is now a vindictive executive who is pulling Medea's financial lifeline (his daughter is the woman Jason has left Medea for) and the Chorus has become a nasty clique of yummy-mummies.

But for all this breath of fresh air, Medea herself is a reduced version of her powerful self. Here, Medea is a seething, vindictive, angry woman right from the off. Whenever Jason is nearby she instantly flies off the handle and she hasn't a nice word to say to or about anyone.

By depicting her as a one-note shrieking harpy incapable of calm, rational thought, this Medea is diminished. We lose her complications, we lose her humanity. We lose the ability to empathise with her, and we also lose that stone cold terror that comes from the 'there but for the grace of God' feeling when we understand where she's coming from - and where she is heading.

The powerful Medeas are the ones that take you with her. The ones where there is a change in her character, starting off devastated but rational only to unravel to commit the most unspeakable of crimes. For even that crime to become rational. This Medea though lacks that journey. This is a one-note Medea who starts off screaming and shouting and stays that way throughout. The journey isn't evident.

Though I suspect there is an argument for saying, 'well, when a man cheats on you and leaves you, you have every right to be angry.' For sure. But this is Medea not just anybody and, for me, I've always relished the study of Medea that blends the rational and irrational, the anger with the calm, considered motive.

For as long as forever, women have always been pigeon-holed as the shrieking hysterics and men as the sober, rational mind - that there is this clear division in behaviour that can be explained by gender. That is sexism, after all. This Medea plays up to that stereotype. She becomes that cliché and, as a result, her power is diminished.

There is also the unnerving sense that Rachel Cusk has actually written herself into Medea, that there is an element of autobiography in this version which sees Medea, now a writer, hated by the other mothers in town and devastated by the collapse of her marriage.

Though I applaud the risks taken - no story should ever be sacrosanct - and Kate Fleetwood's performance is full-blooded and passionate, for me, too much has been lost here. Medea is a reductive version of her true self. Never is she powerful or in control of herself or the chain of events.

And it's hard to believe that this Medea - the one in front of us - would ever kill her children. The character just didn't justify the crime. I didn't buy it, it wasn't believable in the circumstances being played out in front of us. Unless you were viewing her through the prism that she was always mad and completely unstable. And if that's the case, then this is not a good Medea. Not for me.

Almeida Theatre, London to November 14, 2015

Image Credits:

1.Kate Fleetwood in Medea at the Almeida Theatre. Credit Marc Brenner

2.Cast and Kate Fleetwood in Medea at Almeida Theatre. Credit Marc Brenner.

3.Cast of Medea at the Almeida Theatre. Credit Marc Brenner

4.Kate Fleetwood in Medea at the Almeida Theatre. Credit Marc Brenner

Published on October 03, 2015 02:06