Victoria Sadler's Blog, page 4

April 5, 2016

Review: In the Age of Giorgione, Royal Academy of Arts 'Revealing'

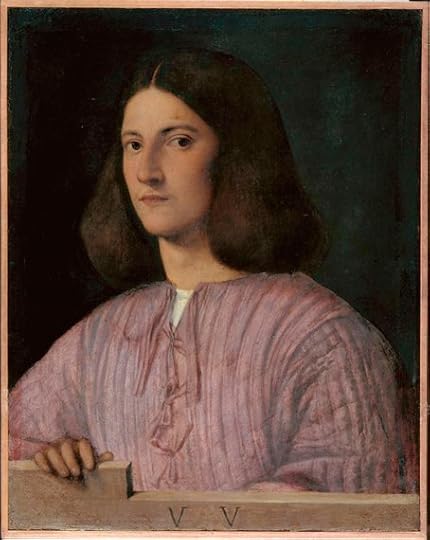

Who was Giorgione? After all, he's hardly a household name and yet the Royal Academy has opened a new exhibition dedicated to uncovering more about him and his work. Well, this is most definitely a welcome exhibition because Giorgione was a brilliant artist in 16th Century Venice, a prodigy who died too young and whose full potential, sadly, went unfulfilled.

Giorgione died in his early thirties, most likely from plague which was at epidemic levels in Venice at the time. But even in his short career, Giorgione was at the forefront of innovations that transformed portraiture.

He was committed to bringing portraiture to life, to have sitters who engage with their viewers, for an element of state of mind, of emotion, to be conveyed. He had no interest in the stiff, blank faced, formal portraiture that the wealthy in Venice had commissioned before. He wanted his portraits to be active rather than passive.

A case in point is the celebrated Terris Portrait, 1506, on loan from San Diego. Like so many of the portraits on display, this one is closely cropped - the sitter's head taking up the canvas completely. But this is an engaging portrait, the man's gaze directly at us though a little elusive, a little enigmatic. Perhaps the influence of the Mona Lisa can be seen here. After all, Leonardo da Vinci was visiting Venice around this time and the opportunity to learn from the Master, perhaps, was taken.

Giorgione was not alone in challenging conventional portraiture, though. He was part of a burgeoning art scene in Venice. This was a rich city. And that meant wealthy merchants and the emergence of sophisticated patrons who wanted to be seen to be encouraging the arts. Giovanni Bellini was the big name at the time, but Giorgione, along with Titian, were leading the young hotshots coming through. They were the ones challenging conventions.

And it's this that leads to the central problem when revisiting Giorgione's work - attribution. Which paintings did he actually paint? Few paintings have any inscription of his name - or any name - and given Titian developed a similar style at this time, some works have been attributed back and forth between them.

By curating a show that brings together a selection of works from the big hitters at the time - Sebastiano del Piombo and Albrecht Durer, as well as Bellini, Titian and Giorgione - the Royal Academy not only brings to life this period of art in Venice, but also highlights the challenges of attribution. When inscription is unavailable, how can we be sure which artist painted which work?

Giorgione is often seen as the principal talent, the primary force. And, what's fascinating is that seems proven as, for me, the highlights are those works where Giorgione's hand is pretty certain.

La Vecchia, 1505, is a powerful portrayal of an elderly woman, widely thought to be Giorgione's mother. The hunch in her shoulders, the thinning hair, even the deep wrinkles in her dry skin. The artist's lesson on the transience of life is clear. The portrait is profoundly realistic, yes, but, more than this, it is also a striking contrast with the idealised beauties that was the representation women were usually reduced to in art at that time (and beyond).

And away from portraiture, Giorgione's landscape Il Tramonto, 1506-10, is absolutely beautiful. A tranquil, rather barren, landscape dominates the canvas; the two men in the painting slight in comparison to the magnitude of the trees and cliffs around them. Unfortunately a restorer, a few hundred years later, has gone and painted in St George slaying a dragon in the middle ground. Quite what possessed them to do that, who on earth knows?

But this aside, there is much to attract the visitor to this compact but revealing exhibition. Whether all those pieces attributed to Giorgione are by him, we can't be sure. But In the Age of Giorgione does a terrific job of showcasing the innovative work of Giorgione, and leaves us to ponder what might have been had the plague not taken this talented artist so young.

Royal Academy of Arts, London to June 5, 2016

Admission: £11.50 (concessions available)

Image Credits:

1. Giorgione, Portrait of a Young Man ('Giustiniani Portrait') Oil on canvas, 57.5 x 45.5 cm Gemaldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preubischer Kulturbesitz Photo © Jorg P. Anders

2. Giorgione, Il Tramonto (The Sunset) Oil on canvas, 73.3 x 91.4 cm The National Gallery, London Photo © The National Gallery, London

3. Titian, Christ and the Adulteress Oil on canvas, 139.2 x 181.7 cm Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council. Archibald McLellan Collection, purchased 1856 Photo © CSG CIC Glasgow Museum Collections

Published on April 05, 2016 11:02

April 1, 2016

Review: Russia and the Arts, National Portrait Gallery 'Dramatic, Intense, Passionate'

The turn of the 20th century was not a happy time in Russia. The Imperial dynasty was moribund and its Tsar, Nicholas II, was a hopeless and feeble leader who inflicted terrible hardship and violence on his people.

Published on April 01, 2016 07:28

March 31, 2016

Review: Russia and the Arts, National Portrait Gallery 'Dramatic, Intense, Passionate'

The turn of the 20th century was not a happy time in Russia. The Imperial dynasty was moribund and its Tsar, Nicholas II, was a hopeless and feeble leader who inflicted terrible hardship and violence on his people. And all this misery and angst of this period of political turmoil is captured in an extraordinary collection of portraits that have been brought together in Russia and the Arts at the National Portrait Gallery.

It is one of those rare and fortunate coincidences that, in the same period as his country was facing extraordinary upheaval, a young industrialist called Pavel Tretyakov began to commission Russia's leading painters to complete portraits of the biggest names in, not just Russia's creative arts, but the world's.

Between 1867 and 1914, Tretyakov accumulated portraits of greats such as Leo Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev, Fedor Dostoevsky, and Anton Chekhov, amongst many others. And the selection here is an impressive glimpse into his collection, which would become the bedrock of the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, Russia's national gallery.

Vasily Perov's portrait of Dostoevsky has the great writer ghostly pale, dressed in browns and beiges, and almost submerged in a shroud of darkness. Whereas in Nikolai Kuznetsov's portrait of Tchaikovsky, the great composer is almost swallowed whole by the black background.

This era of revolution and violence in Russia led to a period of profound self-examination for creative artists as they struggled with their role and responsibility to shed light on the struggles and sufferings of their fellow Russians. Certainly the need to mark a clear distinction between Mother Russia and the corrupt Imperial dynasty was the focus of more than a few.

The art critic Valdimir Stasov stands proud and triumphant in his dazzling red Cossack-style attire in his portrait by Ilia Repin. The writer Vladimir Dal, who worked tirelessly to showcase the Russian language at a time when many in the Russian elite spoke French, is also in simpler, more traditional Russian attire than the Western-style suits worn by others - only his portrait is of an older man, his skin sinking into the hollows of his cheeks, and his white beard a shocking contrast to the dour palette of blacks and browns.

Sadly, though the Romanov dynasty would eventually be toppled, what followed was, arguably, worse. And the repercussions for outspoken creative artists under the Communists were terrible.

Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaia's proud representation of the poet Anna Akhmatova stands as a testament to a woman who would go on to speak out as many of her colleagues and countrymen suffered under the Communist purges. Her work was censored and suppressed, yet she refused to leave Russia. And she suffered too - her husband was executed and her son thrown in the gulag.

But as well as the tragedy, these portraits also demonstrate how experimental and innovative Russian artists were. Mikhail Vrubel's portrait of his wife and opera singer, Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel, displays his radical approach - a form constructed of pale, thick, brisk brushstrokes. And Valentin Serov's portrait of Ivan Morozov captures the sitter's love for avant-garde art in both the painting's composition and style.

This is an evocative collection of portraits that is dramatic, intense and passionate, and it is a show suitably enhanced with music from the likes of Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky played through the speakers.

This rare opportunity to see these portraits has come about as a result of an unprecedented cultural exchange between the National Portrait Gallery and the State Tretyakov Gallery. For whilst we enjoy this exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery has lent portraits of Mary Wollstonecraft, Charles Dickens, Elizabeth I and the Chandos portrait of Shakespeare - amongst others - to the Moscow gallery to comprise Elizabeth to Victoria: British Portraits from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Russia and the Arts is an exceptional collection of works. Many of these works had never left Russia prior to this exchange, and certainly most have never been seen in the UK before. But more than this, it is a genuinely fascinating show that reveals much of the variety in artistic styles in Russian painters at that time, and, in the shadows that haunt their sitters, these portraitists reveal much of the turbulence and turmoil that engulfed Russia in these years.

National Portrait Gallery, London to June 26, 2016

Admission: £6 (concessions available)

Image Credits:

1.Ivan Morozov by Valentin Serov, 1910 © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

2.Baroness VarvaraIkskul von Hildenbandtby Ilia Repin, 1889 © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

3.Anna Akhmatova by Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaia, 1914 © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Published on March 31, 2016 12:02

March 17, 2016

Review: British Culture Examined in New Photography Show at Barbican Centre

If, like me, you're a fan of street photography and social documentary, you'll love Strange and Familiar at the Barbican Centre, a new photography exhibition that examines the changing face of Britain's landscape, its communities and its rituals over the past century.

Published on March 17, 2016 16:10

Review: British Culture Examined in New Photography Show at Barbican Centre

If, like me, you're a fan of street photography and social documentary, you'll love Strange and Familiar at the Barbican Centre, a new photography exhibition that examines the changing face of Britain's landscape, its communities and its rituals over the past century.

Only this show comes with a twist. For it is Britain captured through the lenses of international photographers, rather than domestic talent. How do others see us? What can they see in us, our communities and our conventions, that we cannot see ourselves?

Class remains an ever constant theme in Britain and that didn't pass the photographers by. Tina Barney's works are staged shots of Britain's elite, deliberately reminiscent of the old tradition of the rich and powerful commissioning portraits of themselves to hang on their walls. And contrast these with Raymond Depardon's evocative images of Glasgow in 1980, a city in decline with all the signs of the profound impact of recession, record unemployment and industrial unrest.

On a lighter note, it's perhaps unsurprising that the Swinging Sixties was an era that attracted photographers, with images from Gian Butturini and Frank Habicht reflecting the profound social and political changes that swept through the country.

But as well as these expected subject matters, there are some wonderfully surprising works and unexpected gems.

A highlight for me was the collection from Dutch photographer Hans van der Meer who, in the 1990s, photographed the spectacle of lower league amateur football in the Netherlands. He then extended this project across Europe, including Britain. And his photos are absolutely glorious.

They capture a magical connection between British culture and landscape. The passions of a competitive football match where only pride is at stake played out in the beautiful rolling hills and green fields of the British countryside. The makeshift goalposts, the odd row of terraced houses... There is something so quintessentially British about this, yet obviously this was part of a wider international project so, really, how unique is our culture in a globalised world?

And that tension between unique British identity and global culture comes to the fore in an impressive and vast collection of images of street shoppers, all surreptitiously snapped around The Bullring shopping centre in Birmingham. These photos from Hans Eijkelboom are shown on an ever-looping projection and they reveal so much more than words could ever manage. As these photos of random shoppers pass in front of us, one after the other, you realise they are all wearing the same thing. Endless pictures of people in adidas clothing, endless photos of men in beige jackets, endless photos of women in Missoni-esque prints... Such conformity in the expression of individuality.

Curated by iconic British photographer Martin Parr, the breadth and variety of photography on display is impressive. In addition to the shots of urban and rural settings, there is also some impressive and revealing portraiture.

Bruce Gilden's close ups of everyday people are blown up to such size, and cropped so closely - the frame tight around the face - that every wrinkle, line and spot is so sharp, so imposing, that you almost need to look away, so intense is the intimacy.

I also loved Rineke Dijkstra's The Buzz Club series. Rineke is more well-known for her pictures of young girls in swimsuits, but here she examines the complex conformity and individuality of young women out on the town in 1990s Liverpool. There's a sense of uniform in the obligatory little black dress and blonde hair, yet each has somehow found a way to reflect their own personality in their appearance.

There's an element of nostalgia in parts of this exhibition but don't be fooled - this show does not pull its punches. There are some deeply unsettling reflections of our society included too.

Akihiko Okamura's photos of ordinary lives in war-torn Northern Ireland are pretty sobering, and Axel Hütte's shots from the 1980s of the empty and decaying communal spaces in London's council estates powerfully convey the political change of the period, which led to many of these estates - once seen as dynamic and modern - to instead become synonymous with alienation and exclusion.

But above all, this exhibition is a reminder of how fleeting, how temporary, all these facets of our existence are. Trends come and go, our landscape is constantly changing. Is there something enduring that is quintessentially British? Take the opportunity to visit the show and consider that question for yourselves.

Barbican Centre, London to June 19, 2016

Admission: £12 (concessions available)

Image Credits:

1.Akihiko Okamura Northern Ireland, 1970s © Akihiko Okamura / Courtesy of the Estate of Akihiko Okamura, Hakodate, Japan

2.Edith Tudor-Hart. Kensal House, London ca. 1938 © Edith Tudor-Hart / National Galleries of Scotland

3.Hans van der Meer Mytholmroyd, England , 2004 © Hans van der Meer / Courtesy of the Artist

4.Cas Oorthuys London, 1953 © Cas Oorthuys / Nederlands Fotomuseum

Published on March 17, 2016 13:35

March 10, 2016

Review: Botticelli Reimagined, Victoria and Albert Museum

Botticelli's Birth of Venus is one of the most enduring images in art history. This curvaceous nude, modesty protected only from her flowing locks, rides towards us on the waves of the sea perched in a shell. And that iconic single image is the launchpad for this bold new exhibition at the V&A that examines Botticelli's influence on art and culture, right up to the present day.

Published on March 10, 2016 02:16

March 9, 2016

Review: Botticelli Reimagined, Victoria and Albert Museum

Botticelli's Birth of Venus is one of the most enduring images in art history. This curvaceous nude, modesty protected only from her flowing locks, rides towards us on the waves of the sea perched in a shell. And that iconic single image is the launchpad for this bold new exhibition at the V&A that examines Botticelli's influence on art and culture, right up to the present day.

The big draw to this show is the undoubtedly impressive haul of Botticellis that have been brought together. Over fifty works. That's the largest collection shown of his work in the UK for a generation. The big guns are absent, however. Primavera and The Birth of Venus itself remain in the Uffizi, and Venus and Mars stays on a wall in the Sainsbury Wing at the National Gallery. But still, there are some gems here.

Ideal Portrait of a Lady, 1475-85, is a stunning portrait in profile, the stark black background sharpening the sitter's beauty, and Pallas and the Centaur, one of Botticelli's most celebrated works, displays all of his hallmarks - the scene filing the canvas, the edges of the painting barely containing the bold figures within, with the beautiful, elegant Pallas a study in demure contemplation.

But here's the thing - I'm not sure that Botticelli benefits from having so many of his works on show in one place. You see, Botticelli had a type. A bit of a Leo DiCaprio, if you will. It didn't matter whether he was painting Mary Magdalene or Venus, all Botticelli's beauties were white with flowing locks, tall slender women with long, elegant limbs. Perfect Cupid-bow lips and dainty feet that seemed to float above the ground.

Yup, Botticelli had a singular view of idealised beauty and to see it repeated again and again, as you scan paintings that should be supposedly diverse - religious scenes and portraits of rich patrons, women from different countries as well as backgrounds - numbs more than it excites.

Interestingly, the galleries filled with Botticellis are placed at the end of this exhibition. Yet they bring into sharp focus the first rooms in this show.

The exhibition is divided into three parts, with the beginning dedicated to examining how contemporary artists and popular culture have responded to Botticelli and his idealised beauty, especially the iconic singular image of Venus emerging from the sea.

This is a dynamic and exciting start to the show - but one many will only appreciate, in retrospect, after they've walked all the way through. Dolce and Gabbana dresses stand alongside Warhol silkscreen prints, video footage of Ursula Andress strolling out of the sea plays on loop alongside a blown-up trademark David LaChappelle photo, and there are some really exciting works from the likes of Cindy Sherman and Orlan who investigate how this idealised image still impacts our view of women today.

The second part of the show is the weak link and probably the section you are most likely to drift through.

This section purports to examine how artists from the 19th century rediscovered Botticelli, and how their own work was directly influenced by him and his style. Here are works from the likes of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones. And their women are all glossy haired with iridescent pearlised complexions. Their clothes are all drapey and blowing in a gentle breeze. It's all very idyllic and romanticised, and really not that interesting.

Currently, there is an understandable trend for exhibitions that examine an artist's influence. Not only is it an interesting exercise in art history, but it allows curators to display big names whilst working around the loan restrictions placed around many of their key artworks.

The idea to use Botticelli in this way is a smart one - it's evident that his legacy of iconic images and idealised female beauty can still be seen today, whether it's in fashion, film or art, 500 years on.

That's not to say this show is an unqualified success. But, nevertheless, this is an interesting and, at times, exciting exhibition that really does demonstrate the enduring legacy of one single iconic image - for good and for bad.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London to July 3, 2016

Admission £16.50 (concessions available)

Image Credits: Installations views of Botticelli Reimagined, At the V&A, 5 March - 3 July 2016 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Published on March 09, 2016 11:30

March 3, 2016

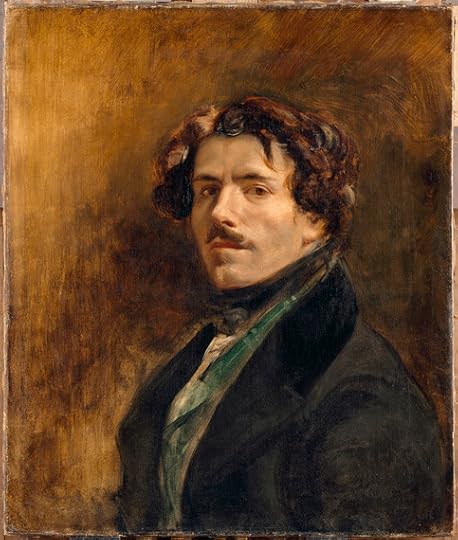

Review: Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art, National Gallery 'Mixed Results'

The National Gallery's latest exhibition is on Eugene Delacroix, the 19th century French artist widely considered the leader of the French Romantic school. This is the first major presentation of Delacroix's art in Britain for more than 50 years. Only this isn't a solo artist show. Instead this exhibition proposes to examine Delacroix's influence on those who followed him, including the Impressionists, and Post-Impressionists, such as Cezanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin.

And that influence, the exhibition suggests, is in both subject matter and artistic style.

Delacroix's works were controversial at the time. Their hurried, unfinished look horrified the critics but inspired many of those new artists coming through who were drawn to this rapid, unconventional style.

There's also looseness in his composition. There's much that's Rubens-esque in the ferocity of Lion Hunt, 1861, and in the dense composition of The Death of Sardanapalus, of a royal court in disarray as the order is given for all to be sacrificed to prevent capture by the enemy.

But there's a surprising informality to paintings such as A Moroccan Mounting his Horse, 1854, and The Women of Algiers in their Apartment, 1847-9. It's an interesting departure. And sometimes this works, and sometimes it doesn't.

There are more than a few examples where these more informal paintings lack energy and interest - figures loitering without much intent, with little to make them engaging. It's easy to walk past exhibits such as View of Tangier with Figures, 1853, and Ovid in Exile among the Scythians, 1859, as there is nothing in these to grab you.

And this is where the challenge in this exhibition begins because, well, not to put too fine a point on it - though this is a show principally about Delacroix, the best works on display are those from other artists.

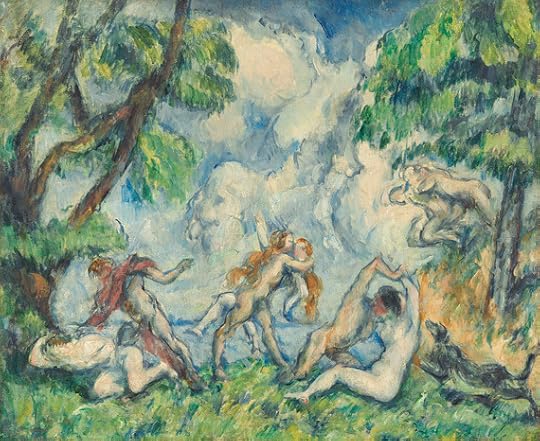

Half the exhibition comprises works by artists of later generations who, it is suggested, were inspired by Delacroix - artists such as Sargent, Renoir, Degas, Gauguin, Cezanne and Matisse. And when works from these artists are hung alongside Delacroix, well, it's Delacroix who seems to come off worse. And it's also questionable how much of what and how the later generation painted can be traced back to just one man.

Delacroix was part of the Romanticism movement and his pictures do have that idealised, highly romanticised style to them, which to be honest is not a style that appeals to me. Pictures of beautiful nymphs bathing cannot impress in the way that Cezanne's The Battle of Love, 1880, and his disarming Standing Nude, 1898, do.

And with regards to subject matter, Renoir's North African travels may have been inspired by Delacroix's trips to Morocco, but can we say the same when talking about Gauguin and his travels? Cezanne was respectively effusive in his praise when he said 'We all paint in Delacroix's language' but artists have many influences, feeding off multiple ideas from many sources. And they also have ideas of their own.

But that's not to say that those Delacroix works included in the exhibition are all to be overlooked. His Self-Portrait, 1837, is glorious in its expression and colour, and his portrait of Louis-Auguste Schwiter, 1826, is impressive. But by and large, this is a show where the supporting acts come out on top.

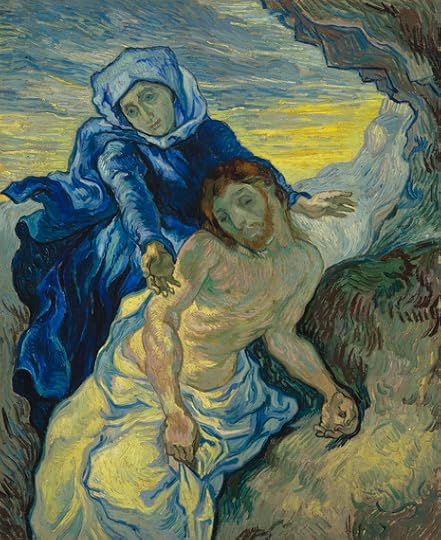

There are a couple of Van Goghs on show and they are beautiful. His Olive Trees, 1889, that he painted while he was staying at an asylum has his distinctive brushwork and beautiful bold colours, as does his Pieta, 1889, inspired by Delacroix's Christ on the Cross, 1853.

And also included is Kandinsky's Study for Improvisation V, 1910, and his thick brush strokes, the electric blues and bright reds, the blurred forms... This is such a radical reworking of such familiar religious subject matter and it excites, and it intrigues.

So overall, this is an interesting exhibition but when the best pieces of work are from Van Gogh and Kandinsky, and it's supposed to be an exhibition about Delacroix, well, something's gone a little astray somewhere.

National Gallery, London to May 22, 2016

Admission: £16 (concessions available)

Image Credits:

1.Eugène Delacroix, Self Portrait, about 1837, Oil on canvas 65 x 54.5 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris (RF 25) © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

2.Eugène Delacroix Bathers, 1854 Oil on canvas 92.7 x 77.5 cm © Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut. The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund, 1952.300

3.Paul Cézanne The Battle of Love, about 1880 Oil on canvas 38.1 x 45.7 cm National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.2. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

4.Vincent van Gogh, Pietà (after Delacroix), 1889 Oil on canvas, 73 x 60.5 cm © Van Gogh Museum (Vincent Van Gogh Foundation), Amsterdam (s168V/1962)

Published on March 03, 2016 03:55

February 23, 2016

Review: Performing for the Camera, Tate Modern 'Selfie Culture is Nothing New'

Selfie culture may be a modern phenomenon but performing for the camera ain't nothing new. And how cameras have been used to capture artists at work and performance art is the subject of this new exhibition at Tate Modern.

Of course, there are two principal ways cameras can be used by artists: there are those where the camera is passive, recording a performance that is fleeting, ephemeral. These are works not necessarily performed for the camera, but captured by it.

And then there is the second group, where artists deliberately perform direct to the camera, or stage a performance specifically for the camera, using the camera as a medium, even as a manipulative tool, to explore and convey a message. And both these approaches are represented in this show.

Unfortunately the exhibition starts off with an awful lot of Yves Klein. A seemingly endless line of photos of him dressed to the nines while he commands naked women around him to cover themselves in paint and roll around on vast canvases laid out on the floor... Yes, I could do with considerably less of that, to be honest.

But, beyond this, lies work from a wide array of artists who use the camera to explore and challenge societally accepted forms of appearance and gender. And this varies from Boris Mikhailov's Crimean Snobbism, 1982, exploring holiday photographs - where the reality of holidays can be so markedly different from the version we try to force through in contrived holiday snaps - through to Linder's She/She, 1981, series of self-portraits where she hides, or should that be 'enhances', parts of her face with cut-outs from 'perfect' images from beauty magazines.

Given this show examines, in part, how artists can perform direct to the camera, the usual suspects are included. There's Ai Weiwei smashing his vase, Andy Warhol capturing Keith Haring painting Grace Jones, and Jeff Koons in self-promotion mode. But there are also plenty of fascinating works from artists who are not household names.

In what is, largely, an exhibition of black and white photography, Jemima Stehli's series of brightly coloured photos grab the eye - as does the content. For her project Strip, 1999-2000, she invited a series of art critics (all male) to watch her undress. In these photos, the camera lens is always focused on the sitter, not Jemima. The series of images are utterly absorbing, displaying subtle, awkward shifts in the male expression and body language as the men try to manage their reactions - being observed whilst observing another in an increasing state of undress.

And as much as is revealed in this show, much is also constructed.

The exhibition comes right up to date with Amalia Ulman's recent Instagram project, Excellences & Perfections, 2015. Here, Amalia created a character, an alter-ego, on Insta and posted a string of updates of herself as a Kardashian-esque figure, living an aspirational lifestyle of privilege and selfies. This is a performance - but it is also a commentary on how we all 'perform' on social media. In this selfie culture, maybe there's a performance artist in all of us now. We're all putting on a show.

Constructing an image is nothing new, but here it is directly confronting us with the challenge of artifice, of constructed reality. Amalia was performing for the camera - but how much did it play into the desires of her many Insta followers? And what does that say about us and our rejection of reality?

This isn't one of those exhibitions that you can glide through in a matter of minutes, briefly admiring the beautiful large works on the wall. Most of the photos on show are not much bigger than those you'd frame on the mantelpiece. They require close study. And that plays to the exhibitions strengths as there are many artists and many messages included in this show that all have something to say and, by and large, are all worth paying attention to.

It's a thought-provoking show, and one which absorbs far more than I'd expected. There's a bit of vanity work in there, sure, but that's nothing new in art. Performing for the Camera is an intriguing snapshot into the relationship between camera and performance art, and how the camera can be used and manipulated by artists to convey their message to a wider audience.

Tate Modern, London to June 12, 2016

Image Credits:

1.Jimmy De Sana, born 1949 Marker Cones, 1982 Medium C-print on paper © Courtesy of Wilkinson Gallery, London and The Estate of Jimmy De Sana

2.Boris Mikhailov b.1938 Crimean Snobbism, 1982. Courtesy of the artist and Sprovieri Gallery, London. © Boris Mikhailov

3.Amalia Ulman Excellences & Perfections (Instagram Update, 8th July 2014),(#itsjustdifferent) 2015. Courtesy the Artist & Arcadia Missa

Published on February 23, 2016 11:06

February 16, 2016

Review: Vogue 100, National Portrait Gallery 'Glamorous & Depressing'

Vogue 100: A Century of Style is an undeniably glamorous and exciting exhibition that showcases beautifully the British magazine's illustrious history. Iconic images of the great and good, taken by the great and good, fill room after room. It's a deluge of beauty, fashion and pioneering photography.

The exhibition, an incredible six years in the making, is here to commemorate and celebrate 100 years of the country's foremost fashion publication. British Vogue's first issue was published in 1916 and, since then, it has been at the forefront of changes in both fashion and photography, eventually becoming so influential that Vogue now even shapes culture, rather than simply reflecting it.

Great effort has gone into curating this show. The many rooms on the ground floor at the National Portrait Gallery have been set aside for his show, and each gallery reflects a decade.

The compare and contrast fascinates - from the celebration of traditional values in the post-war period, through the revelling in wealth of the 1980s, on to the grunge look of the 1990s.

And what also interests is the emergence of the influence of the icon. Whether that be the icon behind the lens - the immediately identifiable style of Helmut Newton, Norman Parkinson, Guy Bourdin, or Mario Testino - or the icon in focus - Diana, Kate, Naomi or Linda.

On to these icons we start projecting, or living vicariously through them. And so these images transform from pictures to admire, to content to desire. We are not browsing for clothes anymore, but browsing for a way of life - one that looks nothing like the ones we actually lead.

And so, as you walk through room after room of the rich and beautiful, it's the content of these beautiful photographs and legendary magazine covers that starts to concern.

In over 100 years, it seems Vogue's main development has been to push an 'aspirational' lifestyle and look that none of us have really got a hope in hell of ever attaining. The clothes are unbelievably expensive, and the models look nothing like us. The aspiration is always youth, the young are always thin, and it is thin that is always beautiful.

Over 100 years, it seems that message has never wavered. A review of the images on show concludes that the only women over 40 allowed to be front and centre are royalty, Vivienne Westwood and Margaret Thatcher. Make of that what you will.

The exhibition makes the point that British Vogue has always sought to blend fashion with broader arts and culture, whether that be literature, art or politics. The text in this particular part of the show adds 'Josephine Baker shared pages with Aldous Huxley' by way of example. Well, in the accompanying photos, Huxley is fully clothed and relaxing at his desk. By way of contrast, Josephine is nude with only a strategically placed drape keeping the image printable. I think that says it all, really.

So for all the glamour and superb photography and illustrations, I found the celebratory feel of the show to be somewhat hollow. What exactly am I meant to be celebrating here? The crushing of the self-esteem of the readers? The framing of many women who have eating disorders as people to admire and emulate? Or that wealth and luxury is what matters above all else?

I wish it were different. The quality of the fashion photography in British Vogue is, and has always been, superb. But what these images represent, what they tell us, has to change.

Vogue 100: A Century of Style is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, from February 11 to May 22, 2016, sponsored by Leon Max.

Admission: £19. Concessions available.

The exhibition will tour to Manchester Art Gallery 24 June - 30 October 2016

Image Credits:

1. Linda Evangelista by Patrick Demarchelier, 1991 © The Conde Nast Publications Ltd

2. Fashion is Indestructible by Cecil Beaton, 1941 © The Conde Nast Publications Ltd

3. Limelight Nights by Helmut Newton, 1973 © The Conde Nast Publications Ltd

Published on February 16, 2016 10:52