Victoria Sadler's Blog, page 11

March 21, 2015

Incredibly Cool Richard Diebenkorn Exhibition at Royal Academy

Some art exhibitions are easy to sell - Impressionist art, Rubens, Rembrandt... These are household names. So when an art gallery - in this case, the Royal Academy - take a risk and put on an uplifting display of works from a comparatively unknown artist - in this case, Richard Diebenkorn - I just want to shout it from the rooftops.

This show is wonderful. If you can, you must go and see it.

Richard Diebenkorn is celebrated as a post-war Master in his native United States - Obama even selected one of his works for the private residence of the White House. In Europe though, he's not that well-known. In fact, the only major solo exhibition of his work was at the Whitechapel Gallery back in 1991.

So what a thrill for the Royal Academy to put on a survey of his work. Sadly this isn't a full retrospective but the 50 works in this show have been selected wisely and together, they are a superb reflection of the three distinct periods of Diebenkorn's creative output.

Diebenkorn first came to prominence in the early 1950s with his abstract works inspired by the landscape and geography around him. He was living in Alberqueque and, then, Illinois at the time so his works have this earthy, muted tone to them.

The second gallery evidences the sharp turn Diebenkorn made in his style. Out went abstract and in came figurative and identifiable landscape art. And the palette transformed also. Diebenkorn was now in California and you can see the bright colours of the West Coast infuse his work.

A wonderful selection of figurative drawings evidence how talented he was. However, given that he had already achieved some success as an abstract painter, the sudden shift surprised many - especially given that figuration wasn't that fashionable.

Nevertheless, Diebenkorn had felt his abstraction was missing something, that his process had become too automatic. His decision to adapt his style paid dividends as he soon became as successful for this style of work as he had been with his abstract.

This development of defined lines, shapes and forms are also reflected in his landscapes where his local Southern Californian scenery becomes discernible in his canvases with roads stretching off into the sea and his brightly lit compositions.

The final gallery sees Diebenkorn moving on in style yet again - or should that be reverting? The room is devoted to Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series, painted in Southern California at the end of the 1960s. The figures, the discernible urban scenes are out, replaced with a return to abstract form.

However this wasn't a simple about-turn; here the lines are sharp and clear and the colours remain bright. The emotional impact of these joyful works is instant and transformative, and the smooth cream walls of the Sackler galleries are the perfect setting for these vibrant canvases.

When contrasted with these strong colours, these high-ceilinged rooms filled with natural light become infused with the effortless Californian cool of Diebenkorn's work. It's as close as you can get to the West Coast without actually being there.

Last year, the exhibitions in the Sackler Wing were amongst the most exiting of the year, with the shows on South American art and Moroni being real highlights. This fresh, superbly curated glimpse into Diebenkorn's extraordinary catalogue of works shows the Royal Academy is off to a great start in doing the same in 2015.

Royal Academy of Arts, London to June 7, 2015

Admission £11.50 (Concessions available)

Image Credits:

1. Richard Diebenkorn Ocean Park #116, 1979 Oil and charcoal on canvas 208.3 x 182.9 cm Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, museum purchase, gift of Mrs. Paul L. Wattis Copyright 2014 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

2. Richard Diebenkorn Albuquerque #4, 1951 Oil on canvas, 128.9 x 116.2 cm Saint Louis Art Museum. Gift of Joseph Pulitzer Jr. Copyright 2014 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

3. Richard Diebenkorn Girl On a Terrace, 1956 Oil on canvas, 179.07 x 166.05 x 2.54 cm Collection Neuberger Museum of Art Purchase College, State University of New York. Gift of Roy R. Neuberger Copyright 2014 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

4. Richard Diebenkorn Cityscape #1, 1963 Oil on canvas, 153 x 128.3 cm San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Purchased with funds from Trustees and friends in memory of Hector Escobosa, Brayton Wilbur, and J.D. Zellerbach Copyright 2014 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

5. Richard Diebenkorn Ocean Park #27, 1970 Oil on canvas, 254 x 203.2 cm Brooklyn Museum. Gift of The Roebling Society and Mr. and Mrs. Charles H. Blatt and Mr. and Mrs. William K. Jacobs, Jr., 72.4 Copyright 2014 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

Published on March 21, 2015 01:34

March 17, 2015

Game at Almeida Theatre is a Game-Changer

If theatre is going to thrive then it must take risks. And the Almeida Theatre takes a risk with Game, a thrilling - and chilling - examination of the tipping point of our humanity that doesn't just excite and disturb, but also transforms the experience of theatre itself.

Carly (Jodie McNee) and Ashley (Mike Noble) are a young couple looking around the apartment of their dreams - contemporary modernist furniture, soft-close kitchen drawers and even a private hot-tub. But this is a property way beyond the means of this young couple yet, intriguingly, by the end of the first scene they have agreed to move in. But how could they afford this?

And then the price of their dream starts to manifest itself.

For the plush apartment is actually owned by John (Daniel Cerqueira) a savvy entrepreneur who is offering punters the ultimate rush - the opportunity to hunt and shoot human prey in their own home. And so introverted ex-soldier David is drafted in (a brilliant performance from Kevin Harvey) to not just patrol the apartment but also to serve the many visitors who rush at the chance to shoot powerful tranquilizer darts at Carly and Ashley at their leisure.

It's a harrowing set-up. Watching Carly and Ashley in their most intimate moments being shot unconscious again and again by the unseen hunters, the punters who are shrouded from the couple by porous walls, stalking their every move through video cameras yet who think nothing of their victims in their pursuit of temporary kicks.

Yet the immersive quality of the production is exciting as we, the audience, are placed firmly in the position of the hunter. We too are behind the walls, we too have access to the security cameras that track the couple's every move, and every piece of their conversations comes through the wireless headsets we're obliged to wear.

As we watch and listen, the wannabe shooters plan and plot around us as, in front of us, the couple obliviously go about their daily lives - two conversations going on simultaneously, two stories to follow and about to collide. And by our very staging, we become complicit in this set-up.

Yet all of this clever staging would be meaningless, little more than a gimmick, if there wasn't a real bite in the writing.

Game is written by Mike Bartlett, the man behind King Charles III and Bull, and it is a bitter reflection on the human condition. It is superb writing that deftly weaves together a whole raft of themes and issues including the human propensity for violence, poverty, housing, responsibility... even PTSD and sexual consent.

And there are so many questions left unanswered at the end - just what is consent in a world of desperate people? Where is that line between exploitation and consent? And just how desensitised are we now? Is there any empathy left?

Though our focus remains on the couple who made the Faustian pact, and the warden who guards them, there are a myriad of other characters - the shooters - who come and go. Every single acting performance is superb with each actor bringing depth and variety to their role.

Direction comes from Sacha Wares who has brought together a terrific balance of pathos and pace. The design team, led by Miriam Buether, most definitely deserve credit for their complete and terrific transformation of the Almeida Theatre.

That there's darkness in this play is obvious but there is also great humour and moments of real heartbreak and tragedy. And for all this to be brought together in a short play of only 60 minutes is an extraordinary achievement. Grab your tickets to see this because Game is revolutionary in design and urgent in substance.

Almeida Theatre, London to April 4, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Mike Noble and Jodie McNee by Keith Pattison

2. Mike Noble and Jodie McNee by Keith Pattison

3. Jodie McNee and Mike Noble by Keith Pattison

4. Jodie McNee and Mike Noble by Keith Pattison

5. Mike Noble and Jodie McNee by Keith Pattison

Published on March 17, 2015 13:49

March 13, 2015

Savage Beauty at V&A Is a McQueen Masterclass

Lee Alexander McQueen was a rare talent - he had that scarce combination of superb craftsmanship and extraordinary vision. And both of these pillars of his strength are on show in this stunning new exhibition of his work.

Savage Beauty is the only major retrospective of the work of Alexander McQueen in Europe. And it is not to be missed as this collection of works by the legendary fashion designer is a masterclass.

The exhibition layout is by theme rather than in basic chronological order. This decision pays off handsomely as not only did McQueen return to certain ideas throughout his career, but it allows the curators to create entire worlds for each theme, immersing us completely in the emotion of the pieces.

Whether it's Romantic Nationalism or Romantic Exoticism, Plato's Atlantis or a recreation of the inspiring Voss catwalk presentation, each room is heady and exhilarating. Sounds fill the rooms, be it birdsong or music, and we are surrounded by some of McQueen's most iconic pieces.

The Romantic Gothic room is filled with McQueen's darkness, his love for Victorian gothic. His bird-women jet black feather dresses stand alongside lace and crystal corsets, all surrounded by towering smoky mirrors.

And this segues into the incredible room of Romantic Primitivism, where the walls are covered with skulls and crossbones and each cave within is filled with garments crafted from horn, skin and hair.

The drama and theatricality is appropriate - this is McQueen after all. But such was the man's talent that not even the emotional intensity of the presentation overwhelms the work on show.

Each piece - and there are over 240 ensembles and accessories on show - stands out on its own merit. And you can see the superb tailoring in each - the seemingly effortless blend of fabrics and objects, whether he's mixing bird feathers with latex, leather bodysuits with crocodile-head shoulder pieces, or crystal-encrusted face masks with red silk gowns.

McQueen drew inspiration from everything around him, whether it was poetry or history, nature or street culture. His collections were infused with these influences. Yet they were always incredibly beautiful - dark but beautiful.

It's that darkness, that subversive side to McQueen's perception of beauty that gave his collections their potency, their power. His works grab you, frighten you even, but they are powerful, sensual and incredibly desirable.

That intoxicating power is reflected in the darkened labyrinthine layout of the exhibition, and this melding of the drama of the curation with the brilliance of the works on show is a winning combination.

Savage Beauty originally showed at Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York but the exhibition has been edited and expanded by the V&A. 66 additional garments and accessories have been included and, reflecting the fact that this show is now in London, a new section has been added focusing on McQueen's early London collections.

The 'worlds within a world' curatorial approach is heady and dynamic - each room is stunning. Yet it's impossible for your jaw not to drop on entering the Cabinet of Curiosities.

Row upon row of headdresses, shoes, costumes and Philip Treacy hats fill this vast, double-height gallery. Interspersed with video footage of almost every single Alexander McQueen catwalk presentation, the room overwhelms you. It's almost impossible to put into words. You crane your neck upwards and all the way to the top are Armadillo shoes, butterfly headpieces, crystal encrusted dresses... It just goes on and on.

That McQueen was a visionary and a genius is obvious but applause should also go to curator Claire Wilcox and her team who have done an incredible job in completely transforming the V&A galleries. The effort and work that must have gone into creating this creative maze must have been profound.

The V&A are hoping Savage Beauty will be their most successful ever exhibition. And it deserves to be. It is unlikely you will ever see a better fashion exhibition.

God, how fashion misses McQueen. Our world is that much duller without him.

Victoria & Albert Museum, London to August 2, 2015

Admission: £16 (concessions available)

Image Credits:

1. Duck feather dress by Alexander McQueen from The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009-10 © Model: Magdalena Frackowiak represented by dna model management New York, Image: firstVIEW

2. Installation view of 'Romantic Nationalism' gallery, Alexander McQueen Savage Beauty at the V&A, 2015 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

3. Installation view of 'Romantic Gothic' gallery, Alexander McQueen Savage Beauty at the V&A, 2015 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

4. Installation view of 'Romantic Primitivism' gallery, Alexander McQueen Savage Beauty at the V&A, 2015 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

5. Installation view of 'Cabinet of Curiosities' gallery, Alexander McQueen Savage Beauty at the V&A, 2015 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Published on March 13, 2015 16:00

March 8, 2015

The National Gallery Opens a Major Impressionist Art Exhibition

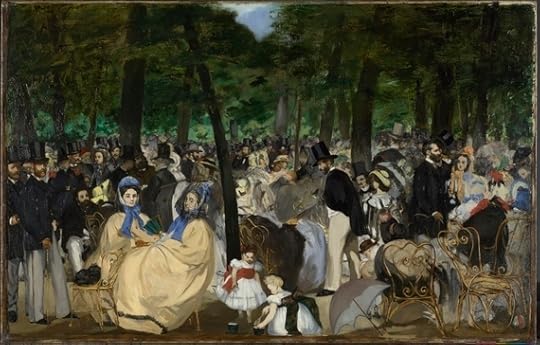

Inventing Impressionism at the National Gallery is an enjoyable, romantic exhibition on Impressionism that showcases over 85 works from this popular period of art. Monets and Renoirs hang alongside works from Pissarro and Degas, early Manets scatter the rooms and there's even a Rodin statue.

For lovers of Impressionism, this exhibition is a dream come true but what is the theme chosen by the National Gallery to connect these works, among them a number of Impressionism's greatest masterpieces which have never been seen in the UK before? Paul Durand-Ruel.

No, it's not a name that often comes to mind when thinking of Impressionist art but Paul Durand-Ruel, an art dealer, was a pivotal figure, if not the pivotal figure, in ensuring the success of Impressionism.

Impressionist art was ridiculed when it first appeared in France in the 1860s and 1870s but Durand-Ruel, an entrepreneurial and savvy art dealer, saw something in these works. He bought works from struggling artists such as Monet and Renoir by the bucket-load, even giving these impoverished artists salaries in exchange for future works.

This was a huge gamble as there was no market for these paintings at all. And indeed, Durand-Ruel was, initially, a reluctant art dealer. It had been his father's business but it wasn't until a chance visit to a Delacroix exhibition that the young man was bitten by the art bug.

But when he saw these new Impressionist works, he sensed an opportunity to seize a corner of the art market for himself. And he invested heavily. Just to give you an idea, by 1922 he had bought around 12,000 pieces of art, including approximately 1000 Monets, 1500 Renoirs and 400 works from Degas. An extraordinary commitment.

With artistic acknowledgement for Impressionists in France difficult, a market made more challenging when war broke out with Prussia, Durand-Ruel took his business overseas. This was a huge gamble - but it paid off. Wealthy Americans in New York snapped up the opportunity to buy these works and soon markets grew in Germany and England.

Durand-Ruel made the market for Impressionist art through a heavy focus on promotional exhibitions and private viewings but it took time, almost 30 years from when he first met Monet and Pissarro in London in 1870-71, to success in New York. The exhibition covers this time frame and demonstrates how crucial Durand-Ruel was in supporting the artists for such a long time. Monet probably wasn't exaggerating when he said, "Without him, we wouldn't have survived."

The exhibition is hung in chronological order, which really gives the curators the opportunity to explain just how close Impressionism came to being a completely forgotten about, obscure part of art history. This approach makes sense and does give us the opportunity to understand what Durand-Ruel was seeing and which pieces of work may not have been created had it not been for his financial support.

Following the artistic development of greats such as Monet, Manet and Pissarro is fascinating especially in the development of their particular styles and preferred subject matter.

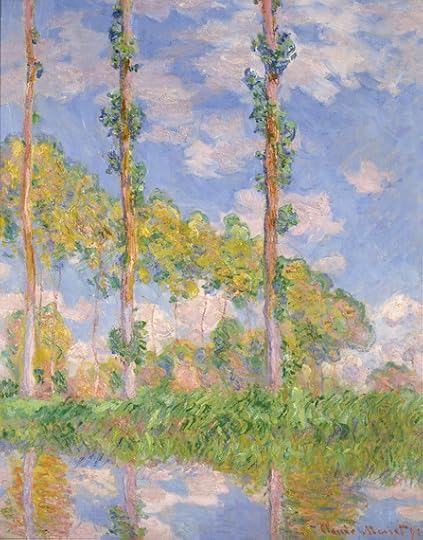

As he looked to drum up interest, Durand-Ruel also started a series of solo artist exhibitions, which wasn't usual at the time and more likely to be for dead artists rather than struggling ones. One of these was for Monet, in 1883. This gives the curators a great opportunity to fill a whole room solely with Monets and this room is a real highlight, especially as it includes the five Poplars paintings which have been brought together via loans from a variety of Museums such as Musee d'Orsay and Philadelphia Museum of Art.

However the decision not to hang the series of Renoir's Dances paintings together, on show here in the UK together for the first time in 30 years, is a strange one. Dance in the Country, Dance in the City and The Dance at Bougival were all painted in 1883, yet the latter is hung separately in the final room of the exhibition. Given that Monet's Poplars were hung together, it is a shame that these three Renoirs were not treated similarly to enable viewers to get the full impact of this series.

Nevertheless this isn't my main gripe with the exhibition. The works themselves are beautiful but given the masterful use of light in Impressionist art, it is frustrating that the National Gallery has chosen to show this exhibition in the dark, subterranean galleries of the Sainsbury Wing.

These works are crying out for whitewashed walls and loads of natural light. Instead they are hung on burgundy and dark brown walls in cavernous rooms. This atmosphere seemed appropriate for the Rembrandt exhibition, which was previously on show in these galleries, but doesn't show these bright, uplifting works at their best.

Furthermore, given that this exhibition is highly likely to be extremely popular, the small rooms will probably get quite cramped again, as happened with the Rembrandt exhibition. So, all in all, the works on show are absolutely worth seeing but prepare for the crowds if you're going.

Admission £18 (concessions available)

National Gallery, London to May 31, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Berthe Morisot Woman at Her Toilette, 1875-80 Oil on canvas 60.3 x 80.4 cm The Art Institute of Chicago, Stickney Fund 1924.127 © The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois

2. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas Peasant Girls bathing in the Sea at Dusk, 1869-75 Oil on canvas 65 × 84 cm Private Collection, Ireland © Photo courtesy of the owner

3. Edouard Manet Music in the Tuileries Gardens, 1862 Oil on canvas 76.2 x 118.1 cm The National Gallery, London, Sir Hugh Lane Bequest, 1917 © The National Gallery, London

4. Pierre-Auguste Renoir Dance in the Country, 1883 Oil on canvas 180 x 90 cm Paris, Musée d'Orsay RF 1979-64 © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

5. Claude Monet Poplars in the Sun, 1891 Oil on canvas 93 × 73.5 cm The National Museum of Western Art, Matsukata Collection, Tokyo P.1959-0152 © National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

Published on March 08, 2015 16:00

March 2, 2015

The Power of Images Examined in Human Rights, Human Wrongs

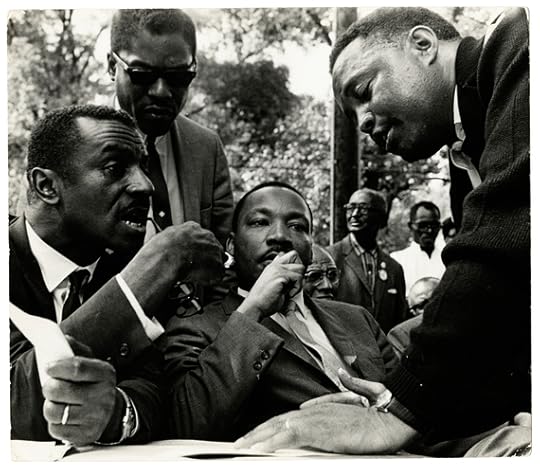

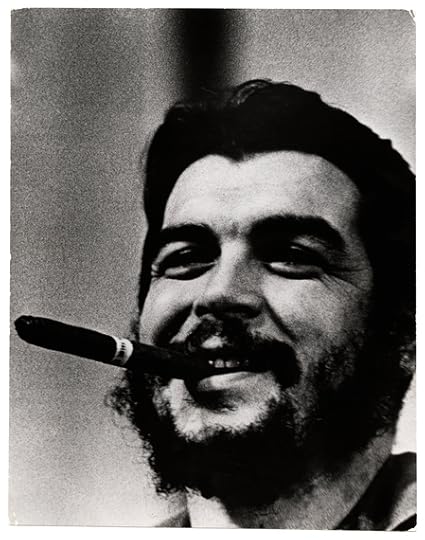

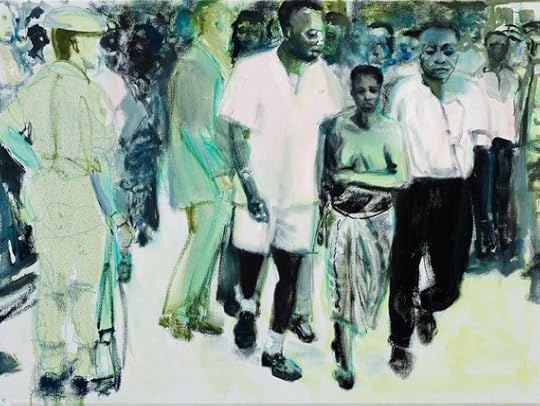

Human Rights, Human Wrongs at The Photographers' Gallery is a thought-provoking photography exhibition that examines the legacy of iconic images. Spanning the years from 1945 to the early 1990s, the exhibition reflects the major political upheavals, conflicts, wars and struggles against racism and colonisation that became particularly urgent after the Second World War.

Powerful images of people, war and societies can tell an important story without any words, but can they fully represent an issue? And what is the long-term impact of these images when they can sear into the human consciousness?

Included in the show are instantly familiar images such as Patty Hearst in her beret and gun, Che Guevara smoking his cigar, a young Muhammad Ali, and Lee Harvey Oswald after his arrest.

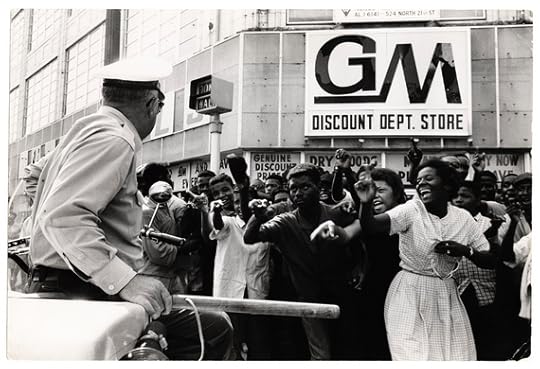

As well as these iconic pictures there are also those photographs that have made their way into our cultural history - a South Vietnamese Buddhist monk aflame from self-immolation during the Vietnamese War, a suspected Vietcong member being shot by a South Vietnamese soldier, and photos of protests from across the United States with black protestors being beaten by white men with batons.

The theme of the exhibition is huge, that of the legacy of images, but this is matched with an extraordinary range of photographs. Over 300 black and white original press prints have been drawn from the Black Star Collection at the Ryerson Image Centre and are displayed here across two floors. Yet the hanging of this exhibition is very clever.

Photos of the bloody aftermath of riots in Mozambique in 1983 are shown alongside similar from the riots in Chicago from 1977. You need the captions to remind you which ones are which. We are not so different. And there are some powerful contrasts too.

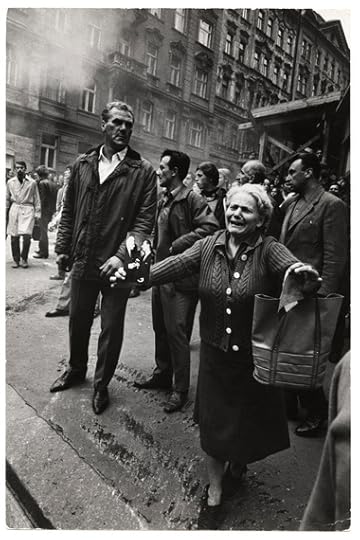

A portrait of Andreas Baader from 1976 is shown alongside a graphic picture of his death one year later. Similarly a portrait of Nobel Peace Prize winner Lester B Pearson from 1957, the year he won, is shown alongside photos of the debris of Dag Hammarskjold's destroyed aircraft from 1961. He too won the Nobel Peace Prize but his fate was very different and it is widely considered today that the plane was shot down in a deliberate assassination.

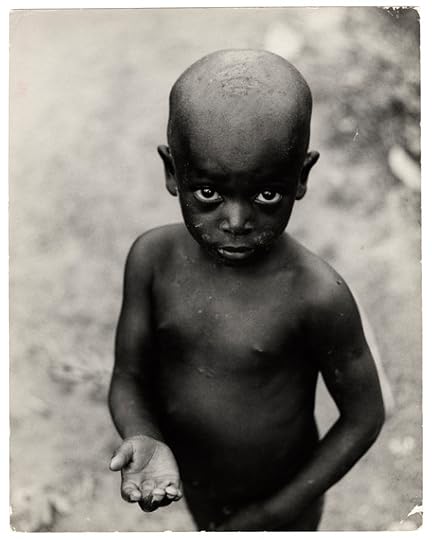

And the endeavour to address this question - what is the lasting impact of these images? - is certainly met. I particularly felt this in the photos of droughts and famines from across sub-Saharan Africa.

The tiny, emaciated starving African children, tummies swollen and bloated with flies crawling over their faces. We all know the pictures. At the time they were crucial documentary evidence of the starvation but today, too many still consider Africa to be a place full of starving children and poverty. An entire continent has become incorrectly defined by these images.

And what about the depiction of victims? Photojournalism provided crucial evidence of the violent oppression of the civil rights movement in the Deep South. These photos are a truthful record of the violence. But what is the impact in our culture of a constant stream of photos of black protestors as victims?

And the exhibition also cleverly explores the deliberate manipulation of photography to serve people's own ends. Henry Kissinger is a man many think belongs in jail for war crimes, but in his photo he's shown on the phone in the White House - a statesman.

Similarly Yasser Arafat's portrait has him as a man of the Palestinian people in his ever-familiar black and white scarf, the traditional keffiyeh. But this was a man who had also amassed a secret fortune of $1 billion by the time of his death, even though Palestinians, who he claimed to champion, lived in poverty.

The scale and breadth of the images collated together for this show is impressive. Its challenge to us is an important one and this is an exhibition well worth seeing, even more so considering admission is free.

Admission Free

The Photographers' Gallery, London to April 6, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Bob Fitch, Martin L. King, 1968

2. Osvaldo Salas, Che Guevara, c.1962

3. Charles Moore, Birmingham, 1963

4. Carlo Bavagnoli, Biafra, c.1968

5. Hilmar Pabel, Czechoslovakia Invasion, 1968

Published on March 02, 2015 12:14

February 24, 2015

Review: 'A View From the Bridge', Wyndham's Theatre

Theatre simply doesn't get better than this. This Ivo van Hove-directed revival of Arthur Miller's A View from the Bridge stunned when it showed at the Young Vic last year and it loses none of its power in this West End transfer.

Mark Strong stars as Eddie Carbone, an Italian-American man who works on the New York docks in post-war America. There's a huge Italian community doing the same and many of them are supporting and hiding immigrants from their homeland who are fleeing the destruction and poverty of post-war Italy for a new life in America.

Yet when Eddie's wife, Beatrice (Nicola Walker), volunteers to shelter her distant cousins Marco (Emun Elliott) and Rodolfo (Luke Norris) who have just arrived secretly on the ships, Eddie's control of his household is destroyed for though Eddie and Beatrice have no children of their own, they are the guardians for their niece, Catherine (Phoebe Fox).

The arrival of the handsome, charismatic Rodolfo turns the young Catherine's head. But their budding relationship angers Eddie, whose own feelings for his pretty niece are confused, and highly, highly questionable.

It's interesting what you remember and what you forget about a production. The tension, the gut-wrenching tragedy in the piece is as devastating as when I saw it last year. Yet I'd forgotten how good the sound and lighting design are.

Don't be deceived by the simplicity in Jan Versweyveld's stripped-back bare stage design as there is some very clever, manipulative use of requiems and stark lighting to ramp up the tension.

And I'd forgotten the smell. It's not often that a theatrical production brings in that sensory experience but the smell of sweat and blood is primal and evocative.

But it is impossible - Im-possible - to write a review of A View from the Bridge and not focus on the performance from Mark Strong. I mean, the right words just elude me.

Mark's performance as Eddie Carbone, a man whose moral compass and self awareness are completely and utterly lost, is just staggering. It was unequivocally the standout performance on the stage last year. To describe it as an acting masterclass or tour de force seem glib. His capture of Eddie's tsunami of emotions contained in the most fragile of shells is devastating. Frankly, if he doesn't win the Olivier for this in April, well, I'm going to do a Kanye!

But though Mark's performance is deserving of the standing o he is apparently getting every night, he is supported by a terrific cast. Each and every performance is stunning but there is a particular and quite brilliant tension between the two women in the piece.

Nicola Walker is superb as Beatrice, Eddie's wife, who is struggling both morally and emotionally with her husband's transfer of affections from her to her blossoming niece. Her performance of repressed anger, jealousy and fear is practically palpable. And this is set against a great performance from Phoebe Fox as Catherine, whose coming of age is a treacherous affair.

Last year, when I saw this play, I wrote "this production is simply faultless." The same remains true today. Bearing witness to this show, one of the most extraordinary theatrical productions you will ever see, is an honour and a privilege.

Wyndham's Theatre, London to April 11, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Cast of A View from the Bridge. Photo credit Jan Versweyveld

2. Cast of A View from the Bridge. Photo credit Jan Versweyveld

3. Phoebe Fox (Catherine) Mark Strong (Eddie) and Nicola Walker (Beatrice) in A View from the Bridge. Photo credit Jan Versweyveld

4. Luke Norris (Rodolpho) Emun Elliott (Marco) Phoebe Fox (Catherine) and Mark Strong (Eddie) in A View from the Bridge. Photo credit Jan Versweyvel

Published on February 24, 2015 11:16

February 16, 2015

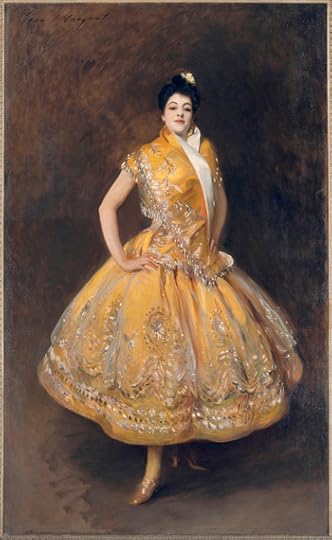

New John Singer Sargent Exhibition at National Portrait Gallery

John Singer Sargent was considered to be one of the finest portrait painters of his generations, yet often his work was commissioned and therefore chained to the requirements of the sitter. This wonderful new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery shows a painter free from those shackles, exhibiting mostly non-commissioned portraits Sargent painted of his friends and acquaintances.

Away from the pressures of commissions these works show Sargent experimenting with styles and settings. Some of the work is quite radical for its time and shows a painter with immense variety and skill. And all these works collected together makes for an exciting and surprising exhibition that challenges the conventional view of this great artist.

Sargent was a great traveller and the pieces on show include works from Sargent's time in Paris, London, Boston and New York as well as his some from his vacations in the Italian and English countryside.

But the scope of the sitters reveals a man very much at the centre of the creative arts with his close friends being many of the leading artists, actors and writers of the time.

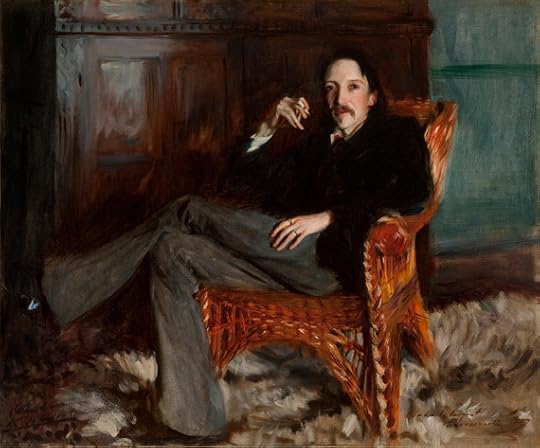

As an example, the only two surviving portraits Sargent painted of his friend and novelist Robert Louis Stevenson are displayed here together for the first time since they were painted in the 1880s. There are also portraits of Auguste Rodin and a striking Claude Monet in profile.

The lack of commission meant the lack of pressure so Sargent experimented with informal and unusual representations in the portraits of his friends. Mrs George Batten, one of the foremost mezzo-sopranos of her time, is shown singing with great gusto, whereas Ellen Terry is painted as a Pre-Raphaelite Lady Macbeth, placing the crown on her head after the murder of Duncan.

This theatricality can be seen in some of the other works on show. La Carmencita is his portrait of the wild Spanish dancer who took New York by storm in 1890. The lady was a notoriously difficult sitter, constantly restless, and this energy is reflected in Sargent's quick brush strokes with parts of the painting seemingly left unfinished. Yet her pose is so defiant, so challenging. There's such a powerful spirit within this portrait.

Similarly, Edwin Booth was a tricky sitter for Sargent. The actor sat for Sargent in 1890 but liked neither the experience nor the resulting portrait. On hearing this, Sargent wiped out sections of the painting and started again. The final result, which hangs in the show, is considered to be one of the artist's finest works.

As well as drama, there's also great beauty in the informality Sargent coaxed from some of his sitters. The wonderful portrait of Madame Ramon Subercaseaux, which opens the exhibition, was an important piece in Sargent's early career - it was painted in 1880. The portrait was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1881, earning him a second-class medal, which meant that he was allowed to exhibit at future Salons without submitting to the jury.

This portrait was painted in Paris and the impact of the French Impressionist movement can also be seen in other works, including the warm and idyllic Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose of two girls playing with paper lanterns in a garden. The fading light as dusk falls is incorporated perfectly into the portrait, giving it a romantic feel.

The exhibition may be comparatively small when compared to the big shows at the Royal Academy and the Tate but this actually works well. Instead of being overwhelmed we feel that intimacy that formed the basis of so many of the portraits on show. A thrilling exhibition full of spirit, life and personality.

National Portrait Gallery, London to May 25, 2015

Admission: £14.50 (concessions available)

Image Credits:

1. Édouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron by John Singer Sargent, 1881 Copyright: Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa

2. Robert Louis Stevenson by John Singer Sargent, 1887 Copyright: Courtesy of the Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio

3. La Carmencita by John Singer Sargent, 1890 Copyright: Musée dOrsay, Paris (R.F. 746)

4. The Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy by John Singer Sargent, 1907 Copyright: Art Institute of Chicago

Published on February 16, 2015 07:01

February 10, 2015

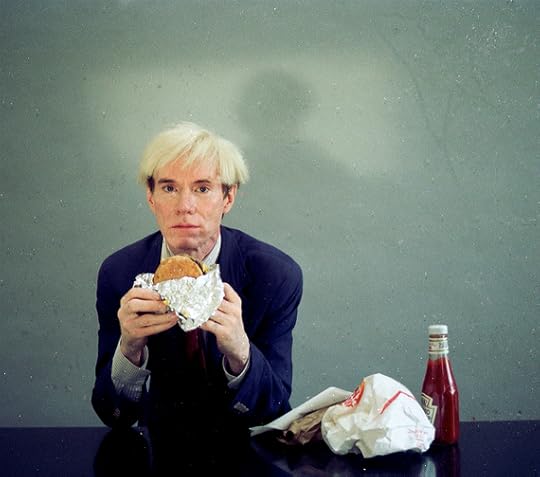

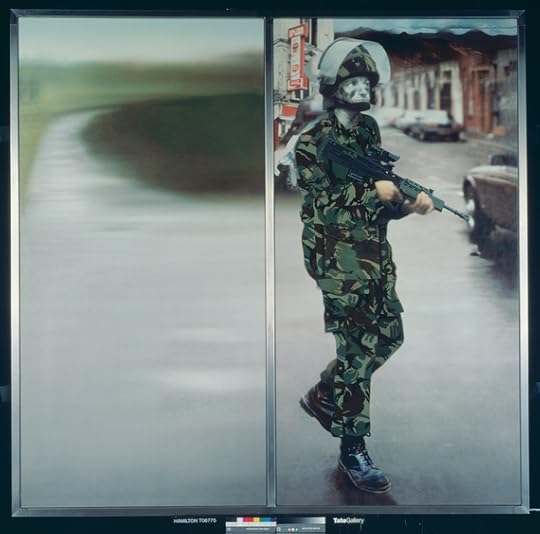

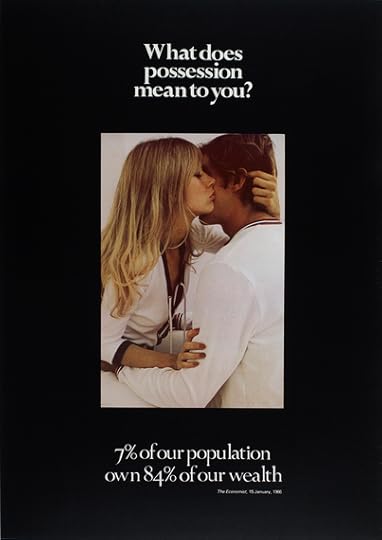

History is Now at Hayward Gallery Searches for British Identity

Timed perfectly to coincide with the General Election, the Hayward Gallery has opened a new exhibition which covers British cultural history from 1945 to the present day. From the Cold War to Thatcher, from Northern Ireland to Greenham Common, from consumerism to BSE, History is Now challenges itself to consider British national identity - who are we and how did we get here.

Seven artists were invited to curate their own section of this exhibition, choosing particular periods and subjects from post-war British cultural history. Over 250 objects are included in this vast exhibition, with every media possible included - from paintings to photographs, from sculpture to scientific surveys, and everything in-between.

John Akomfrah mined the archives of the 600 films in the Arts Council for his section of the show, picking 17 he felt not just reflected British society but also the development of film itself as an artistic medium.

Whereas in his section looking at Britain's attempts to rebuild and reform after WW2, Richard Wentworth includes pebbles and stones Henry Moore collected from the British coastline as well as a decommissioned surface to air missile amongst his exhibits.

Hannah Starkey has smothered the walls in her section with magazine adverts - a blinding, overwhelming representation of the false and contrived images we are bombarded with. Highly sexualised images, photo-shopped bodies, passive objectivity... No wonder we all hate ourselves.

Yet her juxtaposition of these with tender photographs and portraits of real lives and real bodies lends a powerful and positive message of defiance to her display.

That sense of fighting back I also got from Jane and Louise Wilson's section that looked at episodes of social and political unrest. Explicit conflict such as Northern Ireland is represented through paintings from Richard Hamilton, and text and collages from Conrad Atkinson. Whilst Stuart Brisley depicts the social impact of high levels of unemployment in the early 1980s with his profound 1-66,666, where dozens of bloated plastic gloves lie idle in a cage.

Roger Hiorns' section focuses on BSE and it's a dynamic, energetic part of the gallery where sounds of radio broadcasts from the 1990s compete for our attention with unsettling video footage of staggering sick cows and their charred carcasses from the mass cull.

It's a real assault on the senses. Around our feet are Hirst's cattle skulls in formaldehyde whilst on the walls are vintage newspaper headlines, photos of those who died from mad cow disease and extracts from scientific journals on the long-term effects of this contamination of the food chain. One of the documents, from 2013, states that estimates are that 24,000 people have dormant vCJD in them. Who knows whether this disease will develop again from within us?

This section on BSE moved me so much that on getting home, I promptly threw out the beef mince I had in the freezer. The exhibits made me feel sick, queasy and, given the recent horsemeat scandal, it was a direct challenge to us to question who we trust.

And this heavy weight, this depression about the corruption of our authorities and our society, gives this exhibition its power.

Rodriguez King-Dorset produced a film based on the Broadwater riots, Winston Silcott, where quotes from the falsely accused men are spoken by actors over deeply traumatising images. Their screams of "Water, please! I want the water, please. You promised me water!" over footage of men in pain indicate the torture, the criminality of the police who falsified the evidence against these men.

And in Simon Fujiwara's section, which reduces us to our culture, there's Sam Taylor-Johnson's video of David Beckham sleeping representing our shallow obsession with celebrities. There's Hirst's dots - the commodification of productivity, erasing our individuality. And a scale model of Anish Kapoor's bewildering Orbit sculpture built for the London 2012 Olympics.

It drags you down this exhibition and confuses you. What have we done? Look at everything we have to deal with. But there is hope.

Alongside Thatcher and Beckham are brooms used to sweep up the debris left over from the 2011 riots - a sign of a community, a society, that the Iron Lady declared dead - tender prints from Melanie Manchot of her naked mother, bold and fearless in all her natural beauty, and photographs of women at Greenham Common breaking down the fences.

So, who are we? I don't know. This exhibition doesn't give us answers but evidence. And what you see will haunt you and motivate you. A powerful exhibition that doesn't pull its punches.

Hayward Gallery, London to April 26, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Jørgen Leth and Ole John 'My Name is Andy Warhol' from 66 Scenes from America (66 scener fra America), 1982 © the artist 1982/2014. Courtesy the artists and Andersen's Contemporary, Copenhagen

2. Richard Hamilton, The State 1993, Tate, London 2014 © The Estate of Richard Hamilton DACS 2014

3. Victor Burgin Possession, 1976 Gift of the artist 1980 © the artist

4. Tony Cragg Britain Seen from the North, 1981 © DACS 2015 Courtesy Tate Images

5. Gilbert and George World of Gilbert and George, 1981 HD Projection, stereo sound 1 min, 8 secs © the artists, 2014

Published on February 10, 2015 07:39

February 4, 2015

Dark, Haunting and Extraordinary: Marlene Dumas at Tate Modern

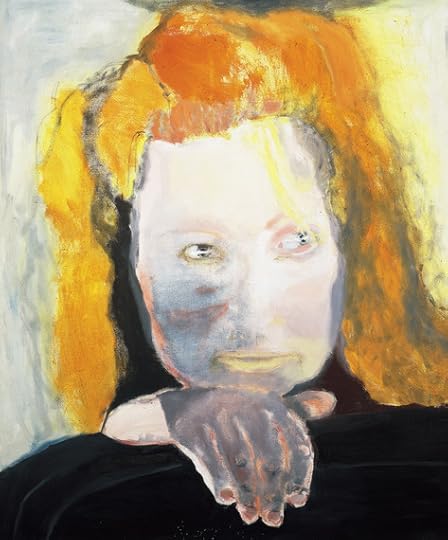

Marlene Dumas is one of the most prominent painters working today. This retrospective at the Tate Modern is one of the most significant exhibitions of her work ever to be held in Europe and showcases her compelling output which explores the psychology of our society today, the importance of the image, and is a fascinating examination of the depiction of women in today's culture.

Marlene was born in South Africa at a time of apartheid and censorship, where simply a picture of Nelson Mandela was considered to be so dangerous that it was banned. This deep and profound relationship between banning an image and infusing it with power and meaning must have made an impact on Marlene as it has shaped her work.

Marlene moved to Europe, to Holland, in the 1980s but she remained fascinated with the image. Preferring to work from photographs and media images rather than real life, Marlene takes pre-existing pictures and re-examines them in a way which brings out their inner reality.

The result is a catalogue of intense, psychologically-charged paintings, which mix art history with popular culture and current affairs. The works reflect on love and death, gender and sexuality, and mass media and celebrity.

Marlene once said, "You change the colour of something and everything changes" and such is the power of the colour palette Marlene works with that her paintings pack a real punch. Whether it's Amy-Blue (2011), the close-up of Amy Winehouse drenched in depressing blue hues or The Painter (1994), the naked child whose deathly pallor is contrasted with the blood-red paint that covers her hands, the colours infuse Marlene's work with a haunting, dangerous, almost sinister feeling.

And this impact of a change in colour is brought out explicitly in Reinhardt's Daughter (1994) and Cupid (1994), two paintings hanging side by side. It's the same image - a baby asleep on a bed - but in one painting the soft pink skin tones exudes warmth and comfort, in the other the angry reds and severe blacks evokes fear and anger.

This exhibition is called The Image as Burden, a title taken from one of the many powerful images on display. This small painting, which is based on a film still of Greta Garbo in Camille, shows one figure carrying another yet it's a pose that resonates with us as it brings to mind images of political violence, with the dead and wounded being carried away, and even the dead Christ in the arms of Mary.

So many of Marlene's paintings are loaded like this. This search for meaning, this heavy weight, the burden of the artist trying to find meaning in an image, fills many of the works on show.

A personal favourite, Losing (Her Meaning) 1988, shows the deathly pale body of a woman face down in water, whilst next to it in Dead Man, a man is floating dead in the water. And opposite is Waiting (For Meaning) 1988, where a naked body lies prostrate over a draped coffin. What does it all mean? The pictures have so much anguish in them.

The power of images fascinates Marlene, whether those images are ones we see in popular culture and in the media, or whether it's the general politicisation of the female body itself.

One room in the exhibition is set aside for Marlene's studies of the female naked body and pornography. In these paintings, a series of naked men and women are painted in a series of provocative poses either masturbating or exposing themselves. As a compare and contrast exercise, it is potent.

As Marlene herself has said, these paintings aren't supposed to be anatomically correct. In fact, far more is hidden than shown but it demonstrates how a picture of a woman touching herself is far more erotic, far more challenging to the viewer, than a naked man.

This censorship of the female form is something that Marlene returns to again and again in her work. In The Trophy (2013) and The Woman of Algiers (2001), Marlene's paintings are based on news photographs of naked women who had been captured and were being shown as trophies to the camera.

Only in the papers, the pictures of the naked women were shown with two thick censorship bars covering those parts of the female body that were considered necessary to censor. Marlene retains those censorship bars in her paintings and, as such, these are a reminder of how female bodies are portrayed in our culture and how, for women, their bodies remains political.

And though these images may be from old wars, Marlene brings this theme up to date in works such as Great Britain (1995-1997), where a painting of a naked Naomi Campbell, the black supermodel, is shown alongside the white princess - Diana - in her soft pink gown and tiara. The black woman naked, the white woman clothed. The pictures say it all.

This is such a stunning exhibition. The works are dark, yes, and they will haunt you but they are also extraordinary and necessary. Marlene Dumas is not an artist that many are familiar with so it is very exciting that this exhibition will bring her work to the attention of a new and broad audience.

The Tate is running a series of events throughout the course of the exhibition to discuss the ideas and themes in this show. Included in these is a talk from Marlene Dumas herself on April 16th, which is sure to be a fascinating discussion.

Tate Modern, London to May 10, 2015

1. Marlene Dumas, The Image as Burden, 1993 Private collection, Belgium © Marlene Dumas Photo: Peter Cox

2. Marlene Dumas, Helena's Dream, 2008 Kunsthalle Bielefeld © Marlene Dumas Photo: Peter Cox

3. Marlene Dumas, Evil is Banal, 1984 Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands © Marlene Dumas Photo credit: Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

4. Marlene Dumas, The Widow, 2013 Private Collection © Marlene Dumas

5. Marlene Dumas, Amy - Blue, 2011 National Portrait Gallery, London © Marlene Dumas Photo: Peter Cox

Published on February 04, 2015 07:24

January 28, 2015

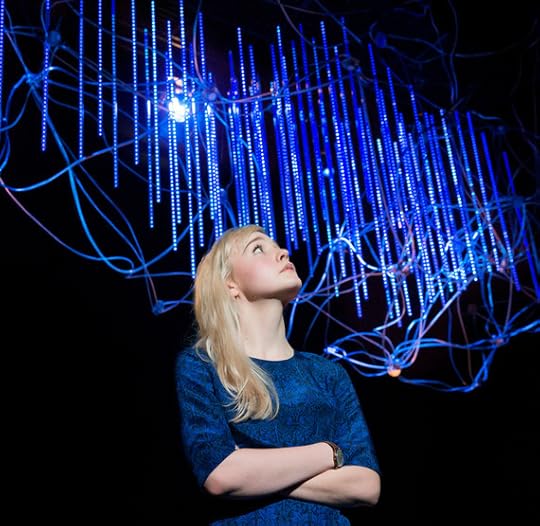

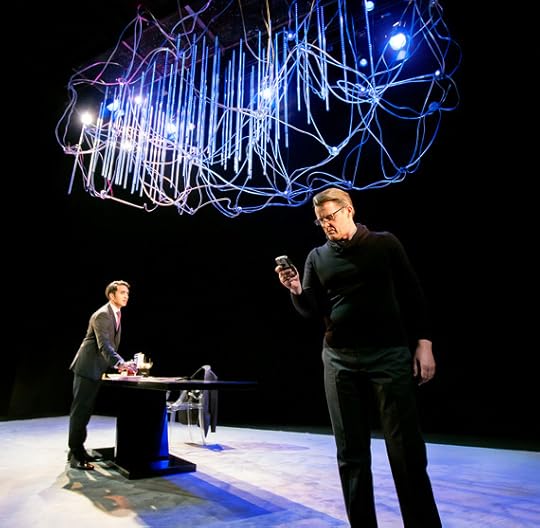

Review: Tom Stoppard's 'The Hard Problem', National Theatre

The Hard Problem is Tom Stoppard's first new play since 2006's Rock & Roll and therefore this is a much anticipated production at the National Theatre. The Hard Problem in hand is simply, what is consciousness? But the play itself is actually hard going.

The story centres around Hilary (Olivia Vinall), a PhD student at Loughborough, and we first meet her engaged in some pretty heavy flirting with her lascivious tutor (Damien Molony) who's only really offering some extra help on her thesis because he wants to get into her pants (his words, not mine).

And how do they flirt? Through a rather heated debate about whether human motivations can ever be truly altruistic. It's a shame that Olivia has been lumbered with the rather naïve part of the debate, that altruism is possible, as I'm not sure that I believe a PhD student would be so childlike in her position.

Those familiar with pop culture, you'll know that this debate has actually been done (better) elsewhere. Now I'm guessing Tom Stoppard didn't watch a lot of Friends but all I kept thinking about was that episode where Phoebe was absolutely convinced that altruism was possible and spent the whole episode trying to do purely altruistic acts before she eventually let a bee sting her because that's what it wanted to do.

But anyway, this pretty much lays out the ground for the rest of the play for the second scene moves on to consider, can computers think? Now, again, this isn't really new ground as Alan Turing's famous paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence actually starts with the question, "can machines think?"

It is a bit bizarre, therefore, that this entire scene takes place without the name 'Turing' being mentioned even once. And it seems even odder that parts of his paper, on the importance that to get a machine to think we must not recreate an adult mind but a child's one and then educate it, are not even included in the debate.

However, the premise of this scene is Hilary's interview with the exalted Krohl Institute where she's pitched against Amal (a welcome spirited and energetic performance from Parth Thakerar) and this question is pitched to both candidates to resolve.

I mention this as this is the only scene where you sense that dialogue this heavy, this detailed, makes sense. Of course candidates would hold forth considering these big questions and debate these big answers. Elsewhere, in the other scenes such dialogue seems out of place and forced.

For example, it seems implausible that two scientists, both before sex and after sex, would turn immediately to intense arguments about mathematical equations, chaos theory and the existence of God. There's even a bit of Gaia theory thrown in - does the world itself have consciousness? But it's a bit much. Surely even scientists want to talk about something else sometimes?

But from this successful interview, we follow Hilary's budding career at the Institute as she takes on a junior, Bo (Vera Chok), and together they conduct a series of behavioural analysis experiments on children of various ages. Sadly these experiments are not actually part of the play. Instead these are performed elsewhere and instead we're told the results rather than shown.

Unfortunately for Hilary, her management of both Bo and the tests are not thorough and this comes back to bite her.

None of this reveals character though and the plot is pretty bare. Instead it's used as a tool to analyse human motivations, and hence we swing back to the initial debate - are we altruistic by nature, or selfish? And in the nature vs. nurture debate, is altruism the natural part of that equation or is our natural state one of selfish desire?

Tom Stoppard's reputation as an intelligent playwright who likes to tackle these big science-philosophy conundrums is well known but, for me, the balance between heart and head in this play is out of kilter. The play doesn't engage you emotionally and so it's hard to be swept up in any of the debates you hear. Little is dramatized and you feel the whole production is just a very loose vehicle for these dry debates.

Direction comes from Nicholas Hytner and it's very subtle. Similarly, design from Bob Crowley is very delicate, unimposing, with a simple but emotive mass of hard wires intermingled with flashing, glowing lights, representing synapses, hanging above the stage.

With dialogue this dense it is hard to do much else as anything overly excessive would be too much, too distracting and we wouldn't know whether to focus on the action or the words. In fact, the characters in this play do very little, there is no great action - this is a play of a series of discussions about big questions - why do we do what we do, and say what we say.

All of the above means that we never really get more than skin deep into any of the characters. What you get is a sense of the playwright, Tom Stoppard, raging against the dying of the light, trying to find purpose in mortality. As a result, this play is a bit frenetic, a bit all over the place, wanting to be a play about everything and, as a result, we end up with a play that neither entertains nor sheds any new light on the great question you sense he is trying to tackle - is there a God or is this all just chance?

National Theatre, London to April 16, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Olivia Vinall - Hilary in The Hard Problem by Tom Stoppard. Image by Johan Persson

2. Olivia Vinall - Hilary, Anthony Calf - Jerry, in The Hard Problem by Tom Stoppard. Image by Johan Persson

3. Parth Thakerar -Amal, Anthony Calf - Jerry

4. Olivia Vinall - Hilary, Vera Chok- Bo in The Hard Problem by Tom Stoppard. image by Johan Persson

Published on January 28, 2015 13:53