Victoria Sadler's Blog, page 14

November 5, 2014

Artists Explore the Digital Age in MIRRORCITY at Hayward Gallery

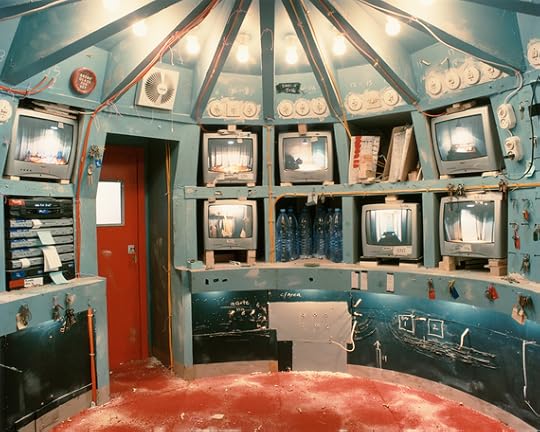

MIRRORCITY showcases new and commissioned work by artists living in London on the challenges and impact of living in a digital age. The exhibition presents artworks in a wide variety of media, from paintings to film, from sculpture to sound. But all of it questions that gap between our virtual lives and our reality.

It's interesting the different approaches the artists have taken, from the deliberately chaotic to the dark but definite. The deliberately chaotic I had expected. Disjointed images shown with unconnected and obscure objects were aplenty, as were sculptures whose purpose or even definition was unclear.

That's not to say there isn't worth in Ursula Mayer's dramatic film clips Gonda and Medea shown with her sculptures Visceral Flowers, Prosthetic Kiss and See You in the Flesh, or in Helen Marten's sculptural assemblages that lack any easy explanation. These pieces are well-observed and have a lot to say. Certainly the virtual world is chaotic, it does lack clean lines and simple definition but I found the unexpected more interesting.

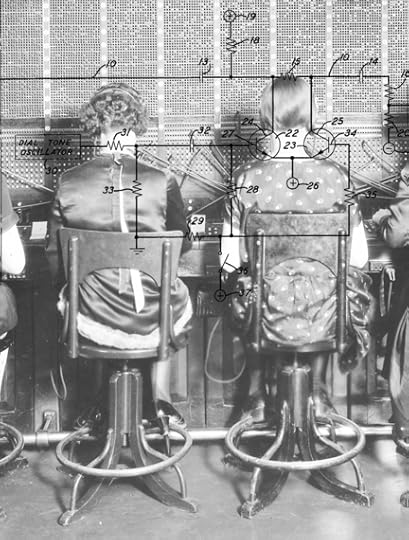

For example, Aura Satz has created a sound installation, Dial Tone Operator, from the dial tone that used to accompany the old telephone exchanges. In this, the familiar tone has been edited into a piece of dance music that sounds like the hum, the buzz, of a city alive with communications - but communications that drown out the sound of humans.

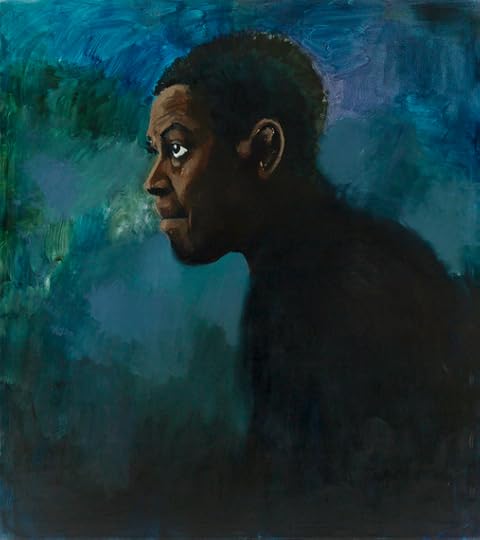

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Tai Shani brought a touch of the surreal to their works, which I really liked.

Lynette presented a series of, what seemed to be, portraits of young black men. They are beautiful pieces with a strong colour palette and a clear sense of the features and emotions of the sitter. Only it transpires that these are not real people but rather paintings of imaginary characters she has created from her imagination.

Whereas Tai created a whole new world in her work, Dark Continent. This installation piece, which incorporates video footage and the spoken word, is of a dreamlike world where a quasi-Ancient Greek temple is filled with glowing candles and projections of a non-earthly godlike woman.

Mohammed Qasim Ashfaq's works also stood out. I liked his dark Black Hole III. The piece is deceptive as from afar, this looks like a simple but dark circle. Yet on closer inspection you can make out groves, lines and even a variety of intensity in its darkness.

I find it interesting though that few of the artists looked at our virtual activity with much positivity. A possible exception to this was Karen Mirza and Brad Butler's work drawn from the Cairo protests that brought down Mubarak.

This was a revolution that was heavily influenced by use of social media and the internet. And in How To Protest Intelligently, they examine the communications and directions sent out to protestors to improve their effectiveness.

I also liked Tim Etchell's examination of the impact of the virtual life on our communications, only he took a more negatively slanted view.

In City Changes, Tim created a sequence of 20 prints where a simple passage about life in the City becomes continually manipulated, edited and exaggerated across the prints until finally, by the end, it bears little resemblance to the first print i.e. To reality. It's an interesting commentary on the manipulation of reality online and how we project ourselves too.

There certainly is a huge diversity of works in the exhibition. Some of it you may love, some of it may just pass you by. But that is a great sign of an exhibition that challenges its artists as well as its visitors.

An unintended highlight for me was watching a visitor, disengaged from the film projection in front of him, choosing to check his Twitter on his smartphone instead. Unintended irony like that, you couldn't make it up!

More and more, the lack of clear definition between our virtual and real worlds is becoming obvious, making this a timely exhibition. MIRRORCITY is certainly a challenging and thought-provoking collection of works and it really adds to our discourse on the gap between our virtual lives and the real world.

Hayward Gallery, London to January 4, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Anne Hardy Building, 2006 diasec mounted c-type print © Anne Hardy, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

2. Aura Satz Dial Tone Operator, 2014 © and courtesy of the artist, 2014

3. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye Uncle Of The Garden, 2014 Courtesy the artist, Corvi Mora, London and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York Photo: Marcus Leith

4. Mohammed Qasim Ashfaq Black Hole III, 2012-13 © the artist Photographer Damian Griffiths

5. Installation view, Tai Shani Dark Continent, MIRRORCITY at Hayward Gallery 2014. Photo: Linda Nylind

Published on November 05, 2014 05:13

November 1, 2014

Wonderful Sigmar Polke Retrospective at Tate Modern

Sigmar Polke was one of the most radical, experimental and influential artists of the past 50 years. And the Tate has brought together an extraordinary and vast collection of Polke's works for this comprehensive retrospective.

Polke had a problem with orthodoxy. He hated it and throughout his career he sought to challenge and overturn expectations about art and artists. He was particularly sceptical about authoritarian ideas of looking at and understanding images.

I say this first, because it's true but second, because this is crucial in getting a grasp on the sprawling variety of media and form throughout Polke's works. Drawings, paintings, objects, film... Polke investigated and used all forms in his work. And nor did he stick to the more usual media of paper and paints. As this exhibition demonstrates, Polke used materials as varied as meteor dust, potatoes, soot, Native American arrow heads and vivid pink faux-fur throws in his work, and he would paint on bubble-wrap, glass, wallpaper and his kids' pyjamas as much as paper and canvas.

Polke was determined to bring art away from the clasps of the elite and into the everyday world hence nothing was considered inappropriate for use in his work.

Born in German-occupied Poland in 1941, Polke's family fled to East Germany in 1945 as part of the expulsion of Germans in the area in 1945, only to then escape to West Germany in 1953. Like other German artists of this time, he was therefore understandably influenced by the legacy of Nazism and the culture of shame and silence that fell over his country in the years afterwards.

But unlike, say, Anselm Kiefer (who is the subject of an exhibition at the Royal Academy), Polke didn't go at this with a sledgehammer. Instead his commentary was more subtle, more subversive.

Polke's early works focused on the resurgence of West Germany and were very much a sceptical response to the, as he saw it, false promises of consumerism that partnered the economic recovery. He hated the insatiable greed generated by advertising and his work often poked fun at the abundance of these goods which many clamoured for such as a figure trying to eat an endless supply of sausages in The Sausage Eater (Der Wurstesser), 1963.

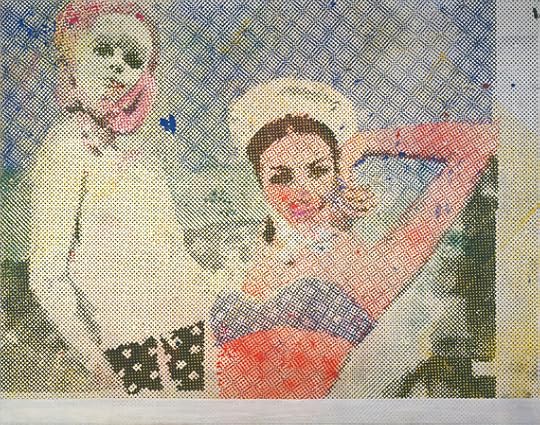

The exhibition contains plenty of Polke's more familiar work, the hyper-pixelated image, where he mimicked blowing up media images up to such an extent that the dots that comprise the image start to take over the image itself. Girlfriends (Freundinnen) 1965-1966 is a great example of this.

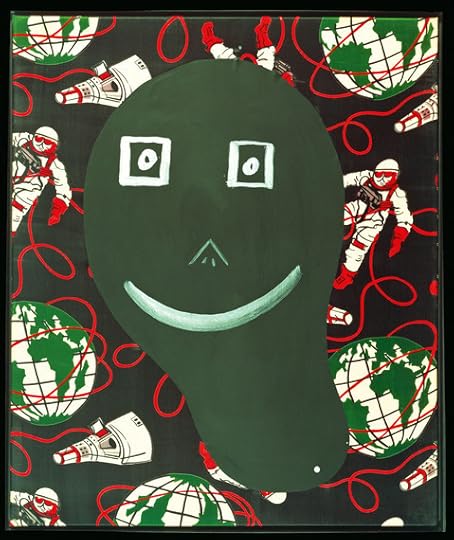

Polke disliked the elitism of art, hence he used such familiar everyday objects in his work, such as clothes and cheap paper. He also disliked people placing artists on pedestals, and he sends all this up so humorously in works such as Polke as Astronaut, 1968 where this big smiley clown face is placed over a cheap fabric of spacemen, or in Potato House (Kartoffelhais), 1967, where he constructed a small garden hut out of garden lattices and then covered the construction with potatoes.

Polke would refer to the Nazi past more obliquely, such as in Konstruktivistisch (Constructivist), (1968), a piece of abstract art in red, white and black (the colours of the Nazi flag) and in his series The Watchtower, 1984, where he repeated an image of an elementary architectural structure, but one that is fused with profound political connotations with its references to the Berlin Wall, to concentration camps.

And still in these he was experimental. In Konstruktivistisch (Constructivist), (1968) he experimented with abstraction and suprematism. In The Watchtower, 1984, some of the works were painted on bubble wrap, media that was sensitive to light so the image fades slowly over time, darkening, fading away from existence, from memory.

From the 1970s onwards, Polke also broadened his own mind both through travel and through the use of hallucinogenic drugs, which he found useful in generating new ideas about subject, colour and scale.

This resulted in an abundance of vast, dynamic work including psychedelic images of Mao Tse-Tung on giant banners of fabric and works that fused sexualised and pornographic images with newspaper cuttings.

But mixing it up as always, Polke would match these with more obscure works such as his large purple triptych Negative Value I, II and III, where the meaning is unclear and the observer is uncertain on the subject.

Polke remained fascinated with mass image production and image manipulation throughout his career. Even in the 1990s and onwards he was looking at new ways of using and abusing the technologies around him. For example, he liked how some photocopiers could warp images they were trying to reproduce identically and he created hand-made lenses as part of the process in creating some of his later paintings.

That the Tate has managed to bring together so much of Polke's work here is impressive. And though the work may seem incomprehensible on first glance, the Tate has done an excellent job with its curation to aid visitors with information on the context and creation of the works on show.

The exhibition is vast, with the works filling 14 large rooms in the Tate Modern, and there is much to see. A wonderful, illuminating and exciting exhibition.

Tate Modern, London to February 8, 2015

Admission £13 (concessions available)

Image credits:

1. Sigmar Polke, Girlfriends (Freundinnen) 1965/66 © 2013 Estate of Sigmar Polke / ARS, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

2. Watchtower (Hochsitz) 1984 IVAM, Institut Valencia d'Art Modern, Valencia, Spain © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

3. Polke as Astronaut (Polke als Astronaut) 1968 Private Collection © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

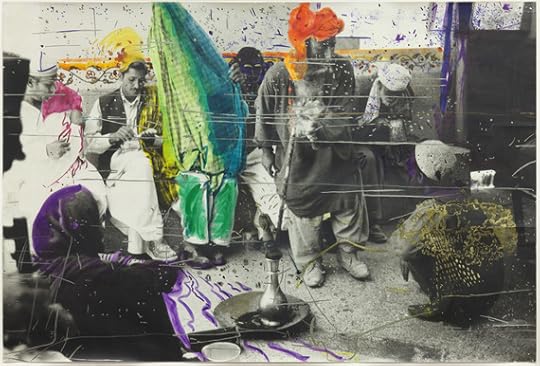

4. Untitled (Quetta, Pakistan) 1974-1978 Glenstone Foundation (Potomac, USA) © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Published on November 01, 2014 04:53

October 29, 2014

Jane Horrocks Stars in 'East is East', Trafalgar Studios

East is East is a bright, well-observed comedy about the issues facing second-generation Pakistani children born and raised in the UK. Starring the gloriously talented Jane Horrocks and writer Ayub Khan-Din, the play has a terrific pace with an excellent balance of humour and pathos to keep you hooked.

The play is set in Salford in 1971 against the background of the Indo-Pakistani War in Kashmir. Zahir "George" Khan, a middle-aged man and father of seven, is incredibly affected by the conflict but his kids aren't interested at all - Pakistan is not home to them.

Instead the kids are more concerned with rebelling against the suffocating authority of their father. The young Sajid has a late circumcision forced upon him when his Dad finds out this was skipped when he was younger and there are rumours of pending arranged marriages for his two older sons Abdul and Tariq.

Jane Horrocks brings a warm humanity to her portrayal of Ella, George's British wife who, for the sake of her family, has her two feet planted in two very different cultures whilst also dealing with the shadow of her husband's first wife back in Pakistan.

Ayub Khan-Din's casting as her husband is an interesting one as he wrote both this play and the screenplay of the 1999 film. I have not seen the film and was too young to see the play when it opened at the Royal Court back in 1997 so this was my first encounter with this popular story.

What grabbed me, what I loved, was that this show is very funny, yes, but it has teeth. There is a dark side.

The kids seem to jokingly refer to their Dad as "Genghis" and at first you think nothing of it as we all think of our parents as dictators when we're kids. But when George is revealed to be a violent husband and father, the sudden change in tone really lands.

However I did feel a sense of hesitancy, of tentativeness in the violence. Ayub Khan Din's George didn't seem as much of a tyrant as his kids were building him up to me. Perhaps the ferocity had been turned down a bit too much.

But for all the understandable emphasis on the star casting of the parents, it is the six children who really grab you, each actor delivering a superb performance. Their work individually and together really evokes a strong family bond. Though they bicker and tease each other mercilessly, the unspoken love between them is obvious in their willingness to confront their parents for the sake of each other.

The direction from Sam Yates is superb. The scenes flow effortlessly into one another, keeping the energy and drive throughout the two-hour running time. Yet though the pace is fast, it is broken up by these sudden flips in tone which really surprise you and they're always given just the right amount of time to hang in the air.

A mention must go to the set design from Tom Scutt. Really bold sets have been a feature of Jamie Lloyd's Trafalgar Transformed seasons and the run continues with an evocative inside-out design that sees Coronation Street-style terraced houses furnished with 1970s style chintz décor.

But though I did enjoy the play, I'm not sure how much it speaks to us now. It's interesting how much I felt this was a play of its time.

The children are adamant that they are British rather than Pakistani and this is shown again and again throughout the play - a stand-out moment being the troubled Sajid shouting "Here come the Pakis" when the Pakistani family arrive to discuss the arranged marriage of his two elder brothers.

Would this be a universal truth today? As a white woman, I cannot say for sure, obviously. But in this post 9-11 age, I feel that cultural identity is a lot more confusing for those of both British and Pakistani heritage.

I enjoyed this production very much but it's interesting how quick it has become dated. I came away more interested in what East is East would be like if it were written today. Still funny? Hopefully, but darker, for sure.

Trafalgar Studios, London to January 3, 2015

Image Credits:

1. L-R Mrs Shah (Rani Moorthy) Maneer (Darren Kuppan) Meenah (Taj Atwal) Tariq (Ashley Kumar) Abdul (Amit Shah) Ella Khan (Jane Horrocks) in East is East. Photo by Marc Brenner.

2. Ella Khan (Jane Horrocks) in East is East. Photo Marc Brenner.

3. L-R Saleem (Nathan Clarke) Ella Khan (Jane Horrocks) Sajit (Michael Karim) Meenah (Taj Atwal) in East is East. Photo Marc Brenner.

Published on October 29, 2014 09:27

October 25, 2014

Constructing Worlds Photography Exhibition at Barbican Centre

Constructing Worlds at the Barbican Centre is a surprisingly emotive photography exhibition that charts the impact of architecture on the global landscape over the past 100 years.

From Depression-era America to 21st Century China, this vast display of photographs shows how our architecture reflects our values and how our landscape has been transformed by economic boom and bust, all of which has been evocatively captured in this vast exhibition that examines the work of 18 photographers.

The instantly recognisable are included such as the towering skyscrapers of New York City lining the City's long narrow streets, the quaint terraced houses on one of London's residential streets and the chaotic urban streets of Naples.

But there are also those who pull our urban architecture almost out of context, analysing its geometric patterns, or isolating peculiar structures such as cooling towers, across the world to compare and contrast similarities and regional variations.

It's interesting how the 18 photographers on show have taken different approaches to their work, often building on and developing the work of those who have gone before.

The exhibition, which is hung in chronological order, starts with the pre-war work of Berenice Abbott and Walker Evans, two influential photographers who were determined to capture the impact of 1930s boom and bust in the American economy in the transformation of New York, with its glorious new skyscrapers swallowing out the communities that inhabited Manhattan at the time, and in the impact of the New Deal initiative on a rural America devastated by the Depression.

Their documentary-style approaches were hugely influential on all that followed but post-war, there was a push from photographers to explore the possibilities that new approaches and new technologies could bring to photography, and the challenges of capturing the landscape we see around us every day in a manner that challenges us and causes us to think.

I particularly liked Ed Ruscha's photos of Los Angeles. There are many ways to photograph LA and many others focus on its crass superficiality or distinctively cool homes with pools, patios and large glass walls.

Yet early one Sunday morning, Ruscha hired a helicopter and took photos of deserted parking lots from the sky. The amount of land tarmacked over and scarred with the constant short sharp lines demarcating parking bays is quite sobering. Yet there's also a bizarre poetry in some if them, such as the drive-in cinema whose parking lot fans outwards. As the song says, "they paved paradise to put up a parking lot."

But the photography on show is not limited to the Western World.

Guy Tillim's photos of urban Sub-Saharan Africa - the Congo, Mozambique - emotionally reflect the death of the African dream. The urgency and passion of African nationalism personified by Patrice Lumumba can be seen in the splendid architecture of hotels and hospitals built in the heady days of the post-colonial era.

But much like the dream of African democracy, these buildings have been abandoned to their decay. Their foundations and walls split and their floors overgrown with weeds.

Yet whilst these photos are infused with tragedy and lost opportunity, Iwan Baan's photos taken in Caracas of the abandoned Torre David complex that was taken over by squatters challenge our preconceptions of squatting as living in squalid conditions.

The 3000 residents of the complex created a project of works to make their homes habitable and there's such a sense of community spirit and positivity in their makeshift churches, shops and homes.

In all these photographs though, there is a real sense of a brief moment of time, as if none of these photos could ever be taken again. Our urban landscape is constantly changing. We're forever layering over the past and redefining our skylines.

Nadav Kander's photography of the banks of the Yangtze River perfectly reflects this. The speed of China's transformation over the past 20 years has been dramatic and the scale of the impact on the Yangtze in particular has been profound with such extraordinary changes as the building of the Three Gorges damn.

Kander's photography captures this revolution. The huge concrete bridges in mid-construction dwarf traditional activities such as bathing and fishing in the river beneath them and the sense of scale in his photos is awesome.

Nor is it just the effects of economics on our landscape that photographers have sought to explore but also the effects of war.

Simon Norfolk has been capturing the relationship between architecture and landscape from Afghanistan to Bosnia, from Iraq to Yemen. His photos are sad not just for the obvious immediate destruction but also the sense of lost civilisations erased or covered over by new occupying powers. They reflect the impermanence of civilisation and the rights of victors to dictate the landscape as they see fit.

As you can probably tell, I found this display quite profound. It's a little depressing how we have been overwhelmed, overtaken by this seemingly unstoppable push for urbanisation and our need for economic progress to be demonstrated in our architecture. There's a real sense of narcissism in man's desire to impose himself over the beauty of natural landscapes.

A remarkable and thought-provoking exhibition.

Barbican Centre, London to January 11, 2015

Image credits:

1. Berenice Abbott Night View, New York City, 1932 © Berenice Abbott, Courtesy of Ron Kurtz and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

2. Ed Ruscha Dodgers Stadium, 1000 Elysian Park Ave., 1967/1999 © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery

3. Guy Tillim Grande Hotel, Beira, Mozambique, 2008 © Guy Tillim. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg (Diptych)

4. Iwan Baan Torre David #1, 2011 Image courtesy of the artist and Perry Rubenstein Gallery, Los Angeles

5. Nadav Kander Chongqing XI, Chongqing Municipality, 2007 © Nadav Kander, courtesy Flowers Gallery

Published on October 25, 2014 03:05

October 22, 2014

Brilliant and Moving Rembrandt Exhibition at the National Gallery

The new Rembrandt exhibition at the National Galley is not only an extraordinary collection of works from this great artist, but also incredibly moving. This show Rembrandt: The Late Works focuses on the painter's last years with works from the 1650s through to 1669, when Rembrandt died.

Interestingly, this exhibition has been hung by theme rather than in chronological order with works collated together under umbrella terms such as 'Contemplation' and 'Intimacy.' Explaining this approach, curator Betsy Wieseman says this is because Rembrandt revisited themes and ideas throughout his career and often worked on different styles and techniques simultaneously.

And this hanging works well in the labyrinth of small rooms in the subterranean galleries in the Sainsbury Wing. Each room is full with paintings, etchings and drawings on a single theme, infusing each section with strong emotion.

In the second room on 'Light and Experimental Technique' is the most impressive loan to the exhibition, The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis. This painting has been loaned by The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Sweden - only the third time the painting has been loaned away from the Academy since it took ownership in 1866. And it is such an important piece as it is a vivid example of Rembrandt's flawless manipulation of light.

Figures are huddled around a table. Bright golden light is on that table, though its source is hidden from us. Yet the light bounces off the sharp metallic blades of the drawn swords highlighting the disfigured face of the one-eyed King.

Rembrandt's unflinching depiction of this darker side of human behaviour can be seen in a number of works on show.

In The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Joan Deyman, a shockingly white corpse lies with his body carved open, a deep cavity open in his chest. But though his body is flat, his neck has been snapped so that his head can be pushed vertical, allowing the Doctor to slice off the top of his skull revealing the damp pink brain.

You want to look away almost instantly, so vivid is the picture. What it must have been like, emotionally, for Rembrandt to work on such a harrowing set-up for so long, who knows, but he was committed to honest, unsentimental observation.

Similarly in his drawings of a woman hanging from a gibbet, the setting and context is removed - there are no gawping crowds or willing executioner - allowing Rembrandt to focus on how the body hung and to examine the features of the woman's face.

Yet in all of the works on show there seems to be a search for, and an investigation of, the full range of human emotions. Perhaps that was the impact of his advancing years and his personal contemplation of legacy and his place in the world, or it may be an outward projection of the difficulties he was experiencing in his personal life.

But these works are not indulgent. Instead the push to develop new technique is clear to see.

The Jewish Bride, about 1665, is one of Rembrandt's most celebrated works and is on show here after being lent by Rijksmuseum. This beautiful painting shows both these sides to Rembrandt - the head and the heart - perfectly.

The husband reaches out to his wife, touching her tenderly on her chest. Her hand reaches up to his though she doesn't look over to him. She doesn't have to as their intimacy and ease with each other's presence and company is complete.

The gold brocade on the husband's sleeve is bold and brilliant, swept on in thick daubs as Rembrandt used a palette knife to apply the paint. This was very much a new technique in Rembrandt's armoury and was not used widely to apply paint at this time, more to mix paints away from the canvas.

This technique Rembrandt uses again in a personal favourite of mine, The Suicide of Lucretia, 1666. This is a tragic picture of a young woman, eyes brimming with tears. Blood is seeping from her chest, staining her white shift and in her hands, the weapon that caused the wound - a sharp dagger. For Lucretia, about to die from her wound, has chosen to commit suicide then live and bear the shame of having been raped.

The gold brocade on her discarded robes has also been applied by the palette knife but, just as with The Jewish Bride, it is the emotion that grabs you - in this case tragedy rather than love.

This exploration of a conflicted mind was a recurring theme in Rembrandt's work in his later years. Another painting of Lucretia hangs in the exhibition. This time she's fully clothed, dagger in her hand, poised to kill herself but wrestling with the torrent of emotions in her head.

Similarly in the mournful The Apostle Bartholomew, 1657, Bartholomew grasps a knife, contemplating the meaning of life and death, and the gravity of his dedication to God for he would be martyred - the knife the mechanism of his death as Bartholomew would be skinned alive.

These heavy emotions may well reflect Rembrandt's personal circumstances as he did not have an easy time in these last years of his life.

Financially, he was teetering on the verge of bankruptcy. So worried was he about his creditors that he transferred the ownership of his house to his teenage son Titus, and then made Titus, who couldn't have been more than 13 or 14 years old, write out a will making his father the sole heir. That must have been tough for both father and son to deal with.

But tragically Rembrandt outlived both his son, who died in 1668, and his common-law wife, Hendrickje, who died in 1663. Indeed one of Rembrandt's self-portraits on show was painted in 1669, the year of his own death. It is a desperately moving representation of a man in terrible health and with the weight of the world on his shoulders. Though only 63, in the painting Rembrandt looks 20 years older.

And in his thin grey hair and troubled, furrowed brow Rembrandt, even at the end, is pushing not only technical boundaries (parts of the hair are defined through Rembrandt carving the end of his paintbrush into the oil on the canvas) but also ever-searching to convey the thoughts of a troubled mind.

National Gallery, London to January 18, 2015

Admission £16 (concessions available)

Image credits:

1.Rembrandt A Woman bathing in a Stream (Hendrickje Stoffels?), 1654 Oil on oak 61.8 x 47 cm © The National Gallery, London

2. Rembrandt Portrait of a Couple as Isaac and Rebecca, known as 'The Jewish Bride', about 1665 Oil on canvas 121.5 x 166.5 cm Rijksmuseum, on loan from the City of Amsterdam (A. van der Hoop Bequest)© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (SK-C-216)

3. Rembrandt The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis about 1661-2, Oil on canvas 196 x 309 cm, The Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Sweden © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

4. Rembrandt The Suicide of Lucretia, 1666 Oil on canvas 109 x 93 cm Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The William Hood Dunwoody Fund 34.19 © The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minnesota

5. Rembrandt Self Portrait at the Age of 63, 1669 Oil on canvas 86 x 70.5 cm © The National Gallery, London

Published on October 22, 2014 09:20

October 16, 2014

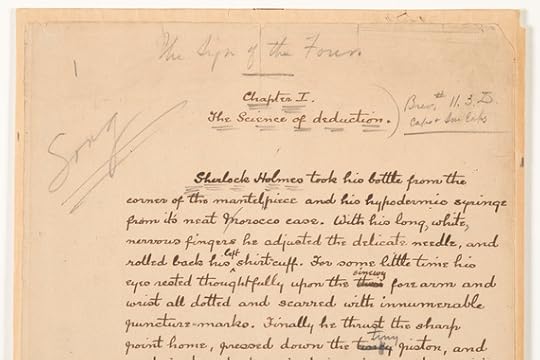

Sherlock-Topia at Museum of London

The new Sherlock Holmes exhibition at the Museum of London is an incredibly dynamic, evocative display that brings to life the man and his city.

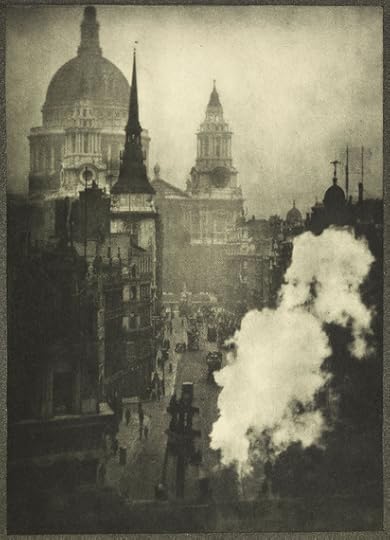

A stunning and diverse range of rarities have been brought together for this show on the world's most popular fictional detective. From the earliest Arthur Conan Doyle notebook to paintings from Monet and Turner, from Chinese film posters to the first recorded ink fingerprints, and from a beautiful array of black and white 19th century photographs of fog-ridden London to a drug syringe. All of these (and more) weave together to create a fascinating show.

And this is no dry, stale museum exhibition, this is a dynamic multimedia audio-visual experience. The curation of this show is superb with video clips and murals shown alongside radio broadcasts and even mocked-up Sherlock deductions to bring to life the images and objects surrounding us.

I was particularly impressed with how the curators pulled apart the movements of Sherlock and Watson in three cases - The Six Napoleons, Bruce-Partington Plans and Hound of the Baskervilles - and plotted these out on a map of London, showing how these two characters criss-cross a city they know like the back of their hand in pursuit of the solution.

And London is so crucial in the Sherlock Holmes stories, almost a character in itself (though obviously the producers of Elementary would disagree).

At the end of the 19th Century, London was at its peak - an imperial capital with a landscape that included beautiful, regal architecture and monuments as well as squalid, grim backstreets. Throw in the dense London fog for a bit of mystery and you have the perfect setting, the perfect backdrop - a melting pot of people and places, from the poor to the powerful - in which to let loose the world's most brilliant detective.

And all of this is practically palpable in the array of photographs, of clothing and in the newspapers from the time that have been brought together here.

But it's not just the visual image of London that's important, but also the image of Sherlock himself for that has been key in securing his status as icon. That instantly familiar deerstalker hat, that curved pipe... Just his silhouette alone is iconic.

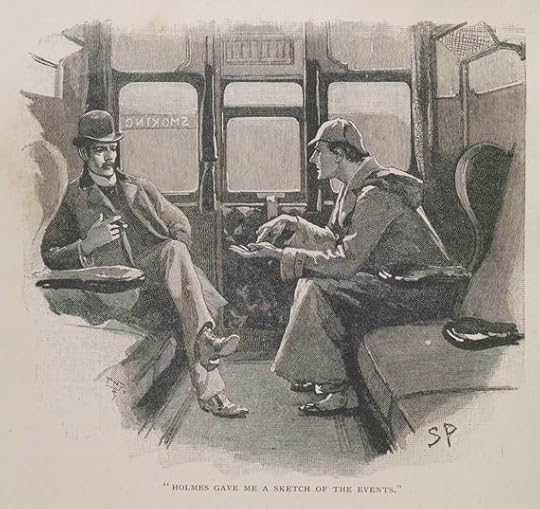

A huge volume of Sidney Paget's illustrations are on show and you really get a sense of how important his images were when they appeared alongside Conan Doyle's words in The Strand Magazine. These were before the days of commercial photography yet this constant reaffirmation of a familiar figure, a familiar face, helped define the detective we still know and love today.

That Conan Doyle created a fascinating character is not in doubt and there's something quite magical about seeing his remarkably neat handwriting in so many of his notebooks and texts that are on show here, including his notebook for the first ever Sherlock Holmes story - A Study in Scarlet.

So how is it possible that Sherlock has become such an enduring hero, even after all this time?

Well, despite the fact that he was created over 100 years ago, Sherlock is a very modern detective. His respect for science and logical deduction would make him relevant even if he were created today (as Moffat and Gatiss have proved).

And Sherlock does not shy away from using every means at his disposal to get to the answers so it's only right that this exhibition reflects Sherlock's darker side too. Sherlock's use/reliance on drugs has always been explicit and so it's only right that a syringe and a burnt spoon are included alongside the ubiquitous deer-stalker cap and curved pipe.

Interestingly, the exhibition refers to the curved pipe being a result of William Gillette's performances on stage rather than from the original text, which I didn't realise. Finding it difficult to deliver his lines whilst also puffing on a straight pipe, Gillette requested the change. And so it came to pass. Amazing how legends are made.

That a significant part of this exhibition is set aside to examine the science of the day and how it feeds the Sherlock Holmes story is a real asset in making this show exciting and provoking.

Theories of phrenology - where deductions could be made from the size of a man's skull - are shown alongside exhibits from the Galton collection of the analysis of fingerprints, which was only emerging as a reliable scientific measure in Edwardian Britain.

Given the popularity of the character, it's no surprise that the exhibition comes right up to the present, including clips from the versions performed by Robert Downey Jr., Jonny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch.

The BBC/Hartswood Films team has been very generous in their loans of items from the show as well as television footage. To the section exploring Sherlock's powers of deduction, they have lent the 'wall of rats' where Sherlock pulls apart the city and some of its key inhabitants as he hurries to prevent a terrorist attack.

And yes, they have also lent that Belstaff coat - or at least one of the many, many versions they have in their wardrobe. And it's very impressive except, you know, not as tall as you'd might expect...!

But anyway, teasing aside, I found this Sherlock Holmes exhibition to be really fascinating with so much to offer. It's almost immersive the way it draws you in to Sherlock's world and I came out not only more informed about Sherlock Holmes but also more excited by him too.

Museum of London to April 12, 201

Admission: £12 (concessions available)

Image credits:

1. Sidney Paget, Portrait of Arthur Conan Doyle, 1897, oil on canvas pre-conservation © Musée Sherlock Holmes de Lucens

2. Sidney Paget, Dec 1892, engraving 'The Adventures of Silver Blaze', Strand Magazine © Museum of London

3. Alvin Langdon Coburn, St Paul's from Ludgate Circus, 1909 © Museum of London

4. Close-up of the first manuscript page of 'The Sign of Four', 1889 © University of California

5. Conservator Melina Plottu prepares Benedict Cumberbatch's coat, on loan from Hartswood Films © Matt Alexander_PA Wire

Published on October 16, 2014 15:38

October 13, 2014

Theatre Review: David Byrne and Fatboy Slim Team Up for 'Here Lies Love'

Here Lies Love is a bold, vivid, mega-kitsch, extremely loud, Studio 54-esque club-thumping, disco-dancing musical about the rise and fall of Imelda Marcos.

David Byrne and Fatboy Slim teamed up to create their version of Evita, only with Imelda Marcos the rags to corrupted riches hero. The show debuted last year in New York and has transferred to London as the debut show for the National's brand new Dorfman Theatre.

And the show is just addictive.

Its heady mix of beats, theatre and archive footage combine to deliver not just a thrilling piece of entertainment but also an educational one as we follow the heady rise of Imelda from impoverished Philippine girl, to glamorous beauty queen who catches the eye of Presidential candidate Ferdinand Marcos and then on to First Lady.

The show is led by an excellent performance from Natalie Mendoza who shines as Imelda. Her voice is superb and she is a cracking actress, bringing real star quality to the production. Dean John-Wilson also impresses as Ninoy Aquino, the democratic opponent to Ferdinand Marcos and (interestingly) Imelda's former boyfriend.

After a wobbly start, this high-octane piece finds its feet and it sears through Imelda's hedonistic life, all set to an addictive club beat. But why has the life of Imelda Marcos been set to a club soundtrack?

Well, creator David Byrne was fascinated by Imelda's love of the New York club scene. When she first came to New York in the Sixties it turned her head. Of course the New York club scene in the late 1960s was legendary and it's that Warhol-esque Studio 54 spirit that's captured in this show.

And there are some memorable numbers in this soundtrack. Star and Slave stands out as Imelda's dedication to her people, her promise to both dazzle them and to serve them. And that's quickly followed by the foot-stomping Please Don't with Imelda portraying herself as local girl done good with the catchy chorus of "Please don't; Don't let them look down on us. Please don't; Like they used to do to me."

I also am a big fan of Order 1081, a dramatic number based around the executive order issued by President Marcos crushing all opposition. It's the moment when you finally feel the weight in the drama. Addictive as all the parties are, the musical needs this gravitas.

How truthful is the story we're told? Well, by framing Imelda as the pill-popping naïve wife of a philandering dictator, it comes close to absolving Imelda of any responsibility for the tyrannical actions of her husband's regime, and indeed her own as she took power when her husband fell ill.

But it's the self-delusion that interests in this portrayal of Imelda, that she really believes that her impoverished, oppressed people would love her for her riches and glamour. And the musical does not pull its punches on the murderous brutality of the regime, or its impact on the people of the Philippines with some remarkable use of news footage to supplement the staging.

In fact, the innovative use of video projections from Pete Nigrini is a real plus. There is little, if any, spoken word in this show. Instead character and location names mix with archive video footage, which is all projected onto the walls of the theatre.

But though I loved much about this show I found the dynamic staging from Director Alex Timbers a distraction as much as an asset.

The floor of the theatre is set up as a club floor with the audience surrounded by platforms and a huge dazzling glitter-ball overhead. The audience/clubbers stand (and some even party) throughout the show but the stages around them are constantly shifting.

I felt sorry for those with standing tickets who were constantly pushed around like cattle by marshals in the crowd. Admittedly some of them didnt seem to mind at all but with every shift of the stages, out would come the marshals, herd the crowd in a certain direction and the crew would move the stage. And this happened after almost every song. I was grateful I had a seat!

There's no doubt the staging is inventive and dynamic but I found it overdone. Of the short 100 minute running time, 15 minutes must be taken up by crew shuffling the stages. That's just too much and it robs the production of energy at crucial points.

This is the first show at the new Dorfman Theatre in the National Theatre building and it's as if the thinking was, hey, we've got this incredibly dynamic new space, let's show off all that this new theatre can do in one show. A shame, as less would have been considerably more.

But that's not the worst sin as, bizarrely, Imelda wears the same pair of shoes throughout the show - a very plain pair of beige high-heels. I know David Byrne has stated this is because Imelda's vast shoe collection wasn't discovered until after the Marcos fled but still, a bit of a missed opportunity.

But though these flaws are frustrating, it doesn't stop this show being a gloriously addictive experience. The show sweeps you up with its high-octane energy and its fresh attitude. I'd rather sit through this show again and again than any new Lloyd Webber.

National Theatre, London to Jan 8, 2015

Image Credits:

1. Natalie Mendoza (Imelda Marcos) Here Lies Love credit Tristram Kenton

2. Dean John-Wilson (Ninoy Aquino) and Natalie Mendoza (Imelda Marcos) Here Lies Love credit Tristram Kenton

3. Natalie Mendoza (Imelda Marcos) Here Lies Love credit Tristram Kenton

4. Dean John-Wilson (Ninoy Aquino) and company Here Lies Love credit Tristram Kenton

Published on October 13, 2014 13:15

October 10, 2014

All-Female Henry IV Takes Over at Donmar Warehouse

Shakespeare's Henry IV Parts I &II have been compressed and transformed into a two-hour prison drama with an all-female cast in this bold production at the Donmar Warehouse.

Prison Officers guard the entrance to the Donmar and they usher us in to a theatre space transformed into the stark, sterile interior of a women-only prison. Brutal and unforgiving overhead lighting glares over harsh metal landings and staircases. Even the audience benches in the stalls have been taken out and replaced with rows of utilitarian plastic chairs.

The prison bell buzzes loudly over the auditorium, the lights darken and our large cast of prisoners are paraded into this grim and worryingly truthful setting.

Given its themes of power rivalries, competing cliques and dynastic succession, Shakespeare's work is an interesting starting point to analyse life inside. And certainly the power politics of life in prison is superbly demonstrated in this radical production from Director Phyllida Lloyd, the second instalment in what will be a trilogy of works at the Donmar.

Harriet Walter shines as Henry IV, the reigning King frustrated as much by subterfuge and betrayal in her ranks as she is by the immaturity of her appointed successor Hal (played with real grit by Claire Dunne).

Harriet Walter is incredible. Effortlessly cool in her demeanour and ruthless in her decisions, power rests so easily on her shoulder and she is a commanding presence on the stage.

As Henry, she battles to defeat the enemies that lie within and crush any rebellion with little support from Hal who has absconded his responsibilities for a life of revelry with the questionable companionship of charismatic prison clown Falstaff (Ashley McGuire giving a great comedic performance).

Some may (sadly) see the all-female cast as gimmicky but after the first few moments, it barely registered with me, so convincing were the performances. However, one thing I will say is that though the cast is excellent at the dramatic and exciting scenes, there is awkwardness across the board where emotional, even physical intimacy is required.

I think it's important that productions are prepared to challenge Shakespeare, re-interpreting it and making it relevant and exciting for modern audiences. With that in mind, I love the decision to transport this play to a prison. The setting is certainly evocative but the challenge with transporting Shakespeare to a profoundly different setting is always that, away from its more usual location, the text can seem nonsensical.

For example, Hal's ambush of Falstaff's attempted robbery in a forest makes no sense in a prison as obviously, none of them can leave the building. Likewise, the carve-up of Britain between the competing clans seems odd. The adaptation requires a real suspension of disbelief but if you go with it, the production pays dividends.

For me, the greater challenge is in following the plot, especially if you are unfamiliar with the text. Two very long plays have been condensed into a sharp, energetic two hours. The pace is quick and rarely lets up. If you are unable to follow what's going on, you can get left behind very quickly.

And though compressed versions of this play have been around for a while, the unique location, the large cast (there are 14 actors in this production) and the very quick pace means that it's hard to place who everyone is in the context of the story and appreciate exactly the importance of everything taking place in front of you.

If you really know the text, this production of Henry IV fascinates. Its commentary on the challenges and concerns of life inside are necessary and relevant. But sadly if you're not completely au fait with the text, you might get a little lost.

Donmar Warehouse, London to November 29, 2014

Image Credits:

1. Ann Ogbomo (Worcester) and Harriet Walter (King Henry) - photo credit Helen Maybanks

2. Clare Dunne (Hal) - photo credit Helen Maybanks

3. Elizabeth Chan (Peto) Sharon Rooney (Gadshill) Ashley McGuire (Falstaff) Karen Dunbar (Bardolph) and Cynthia Erivo (The Earl of Douglas) - Helen May

Published on October 10, 2014 01:37

October 6, 2014

Review: Kristin Scott Thomas in Electra, Old Vic Theatre

Electra is not an easy story to love. The tale of a woman, Electra, who plots to murder her mother the Queen of Mycenae, Clytemnestra, and her new lover, the King Aegisthus, for their murder of her father, Agamemnon, is not the most joyful.

Nor is Electra an easy character to love, especially as we come to understand why Clytemnestra murdered her tyrannical husband. But we're not given much opportunity to warm to either the character or the story in this rather heavy-going production.

I know Greek tragedies aren't easy for modern audiences. Everything is very literal in Greek tragedies - people say what they think and mean what they say. Subtext is almost non-existent and the emotional weight is often very, very heavy.

But though this challenge to reinterpret the material can be daunting, it should be a challenge to be relished. Anyone who saw the recent adaptation of Medea at the National Theatre with Helen McCrory directed by Carrie Cracknell will know that bravery can often pay dividends.

Carrie Cracknell brought a lot of innovative ideas to her Medea, including using a new adaptation from Ben Power, incorporating contemporary dance and a score from Goldfrapp.

Some similar approaches have been taken here. Frank McGuinness has written a new adaptation of Sophocles' Electra and PJ Harvey was brought in for the music but equivalent success has not been achieved.

Too often this production seemed to be played for laughs, which is a bit odd for a Greek tragedy. And in the brief moments of emotional drama, PJ Harvey's heavy music pushes the scene to overwrought melodrama. The music doesn't seem to enhance the production. Silence would've been more profound.

The star attraction is Kristin Scott Thomas in the central role and she certainly is a commanding presence on the stage. Her Electra is full of anger and bile but unfortunately not much else. She is bitingly caustic throughout the show, never showing any doubt over her determination to have her mother killed.

Her angry sarcasm I found a bit exhausting and it robbed the production of much pathos and also robbed her character of much inner turmoil. There is room in the script for variety, such as the scene between her and her softer, kinder sister Chrysothemis as Electra tries to persuade her younger sister to kill their mother. There was an opportunity there for emotional blackmail, for manipulation, but instead the scene is played almost for laughs.

The supporting cast though is excellent. In particular, Diana Quick as Electra's mother brings real internal conflict to her role, pulling on our heart strings a lot more than the main character. You can really feel her wrestling with her conscience and her feelings towards her exiled son who she knows is sworn to take vengeance for the murder of his father. As she pleas to those around her, "A mother never stops loving her children" you really feel it.

Liz White also impresses as Electra's younger sister, Chrysothemis, caught between the love for her mother and her concern for Electra.

The Old Vic Theatre remains set in the round for this production, as it has been for this year, and this works wonders for this production. Electra is a very intense piece and the intimacy of showing in the round is a real benefit.

Director Ian Rickson maximises this opportunity well and the movement from the actors is great. Watching Electra and her mother circle each other in their scene together was a real highlight, especially with the women of Mycenae weaving in-between them constantly to prevent physical confrontation.

The climax of the play is actually when the production is at its strongest - the melodramatic music is gone, the sarcasm and laughs have evaporated and instead we're faced with the horror of Electra finally getting what she wishes for.

It's a harrowing moment but it's just a shame that the previous 90 minutes were such a struggle to get through. There have been better high-profile adaptations of Greek tragedies this year on the London stage, which puts this in the shade somewhat.

Old Vic Theatre, London to December 20, 2014

Image Credits:

1. Kristin Scott Thomas (Electra) - photo credit Johan Persson

2. Kristin Scott Thomas (Electra) and Jack Lowden (Orestes) - photo credit Johan Persson

3. Kristin Scott Thomas (Electra) - photo credit Johan Persson

Published on October 06, 2014 12:20

October 3, 2014

Review: Roger Allam Stars in Seminar, Hampstead Theatre

Triple Olivier-Award winner Roger Allam is the star draw in Seminar, a surprisingly absorbing if somewhat unbelievable play about a bitter but famous novelist teaching a group of starry-eyed aspiring writers.

Roger Allam is on fine form as Leonard, a bitter, arrogant novelist whose best days are behind him and who is reduced to giving expensive private writing classes to those rich enough to afford his patronage.

The play is written by Theresa Rebeck and is a transfer from Broadway where Alan Rickman played the difficult and belligerent teacher. Her play is a bit of a love letter to writing, how hard it is and how fine the balance is between truth and pretension. And there's plenty of withering one-liners to generate the laughs such as "Life is complicated. People are complicated. If you can't figure that out, you'll never be much of a writer."

But though the word play is sharp, the plot is very thin. And it is therefore somewhat ironic that in a play about creative writing, it is the writing that is weak.

There are no real stakes of any consequence at jeopardy for any of these characters. So what if none of them become successful writers? None of them are going to lose their homes or respect from their parents if they don't. There's nothing at risk for anyone, which makes this play incredibly hollow.

Also, every character is a cliché, whether it's the cantankerous teacher as jealous of his students as he is insulting, or it's the trust fund spoilt rich kid in her Upper West Side apartment, the sex-obsessed beauty who's happy to screw her way to the top, or whether it's the not-as-rich kid with a chip on his shoulder about his lack of advantage.

I have seen many plays with stereotypes work. The issue here comes from these persons then starting to act out of character, not performing actions that should be the natural next step.

You see, the theme of this play really is, what are you prepared to do for success? There are those who want to work for it, to succeed on merit, like spoilt rich kid Kate (played superbly by Charity Wakefield). She wants desperately to impress Leonard with her writing, only she's never worked for anything in her life.

But will she learn from the other woman in the class sex-kitten Izzy (played with real vibrancy by Rebecca Grant) who beds Leonard, in her eyes a realistic necessity to succeed? Only Izzy then promptly shacks up with loser not-as-rich-kid Martin (Bryan Dick), which makes no sense as he has no contacts and can't get her anywhere.

And the way these four young writers interact with Leonard, this famed novelist, isn't believable. Right from the off they are in his face, giving him backchat and hurling back insults as soon as he starts to tear up their work. Really? I mean, wouldn't you be a little bit more in awe by him to start with?

So given these faults - and they are profound - it's somewhat surprising that this play does keep you absorbed for the two-hour running time. How is that?

Well, for one, the acting is superb. It really is excellent. Roger Allam obviously. Look, the guy's so talented he could make the phone book sound like Shakespeare and here he wrings out every last drop from the script. His Leonard is arrogant, yes, but Roger Allam's steady reveal that maybe this bitterness is born from a need to shake his students to reality rather than to patronise them is intriguing. Is his absolute cruelty a form of kindness?

But immense credit must also go to the four actors who play his students - Bryan Dick, Charity Wakefield, Rebecca Grant and Oliver Hembrough. They are lumbered with clichés but bring real energy to the play and there's plenty of development of sub-text and silent conversations as secrets are revealed and power balances shift.

And the main character here, which is Kate, is an active protagonist. She does take matters into her own hands after Leonard rips apart her book that she's spent six years working on. Some of her decisions and choices are a little unbelievable, and the supposed twists in the plot you can see coming a mile off, but nevertheless at least she keeps driving the plot forward and forcing the status quo to change.

The direction comes from Terry Johnson, who wowed last year with his tight Sigmund Freud/Salvador Dali farce Hysteria in the same theatre. This year's play is not as dynamic but there are some good pace changes, from the slow, long silences the creative writing classes fall in to as Leonard paces the room weighing up the latest efforts from his students to the snappy fast-paced bickering that the classes descend into as Leonard gives his sneering feedback.

So how to look at Seminar overall? I guess it depends whether you're in a cup half empty or cup half full kind of mood. If it's the former, you'll be wondering why on earth a great such as Roger Allam agreed to be in this play. However if it's the latter, you'll enjoy the fact that you'll bear witness to some superb acting that prevents the lacklustre writing from taking over.

Either way though, there's enough here to keep you entertained for two hours, though it'll probably fall pretty quickly from your mind soon after.

Hampstead Theatre, London to November 1, 2014

Image credits:

1. Roger Allam as Leonard in SEMINAR. Photo © Alastair Muir

2. Charity Wakefield as Kate and Bryan Dick as Martin in SEMINAR. Photo © Alastair Muir

3. Rebecca Grant as Izzy in SEMINAR. Photo © Alastair Muir

Published on October 03, 2014 02:36