Michael May's Blog, page 110

October 4, 2016

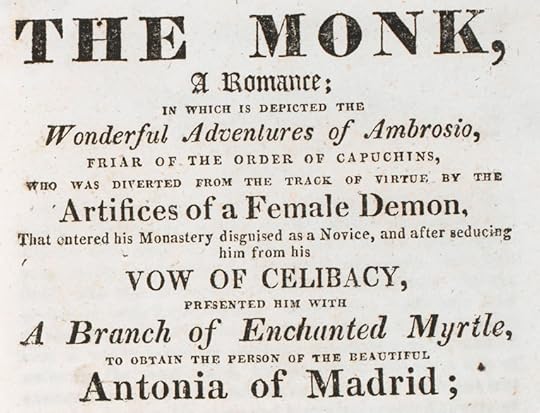

31 Days of Gothic Romance | The Monk

I want to make it clear that my focusing on gothic romance for 31 days isn't because I'm some kind of expert on it. I love the genre, but I'm way under-read in it and one my reasons for doing this is to build a list of books and other things that I want to experience. Matthew Lewis' The Monk falls into that category.

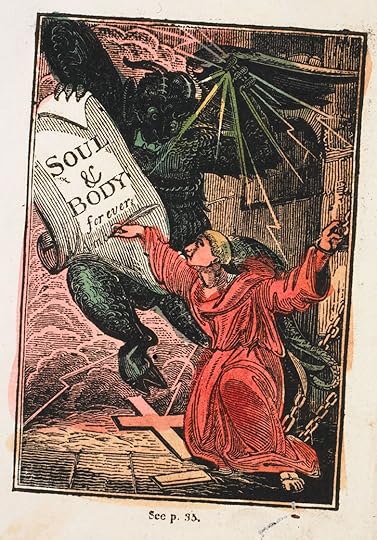

The innovation that Lewis brought to the genre was luridness. It had been relatively chaste up to that point, with horrors mostly being threatened or suggested. Lewis' titular character doesn't just threaten and menace an innocent young woman; he does terrible things to her. And to other characters in order to get to her. And the novel spends a great deal of time chronicling the monk Ambrosio's fall into depravity. He's already not a nice guy as the novel opens - he's proud and he lusts after the Virgin Mary, to start with - and he sinks deeper from there, encouraged by supernatural forces.

The Monk ticks all the boxes expected of a gothic romance, but cranks them up to 11 in a way that made it as popular as it was condemned. People loved to talk about how blasphemous and immoral it was almost as much as they loved to read it.

One of the people it bothered was Anne Radcliffe, from yesterday, who liked to evoke chills by suggesting things unseen. Like Alfred Hitchcock, she believed that what the audience imagined was always more powerful than what was explicitly seen or described. Keeping the analogy of movie directors, Matthew Lewis was more like Wes Craven, wanting to horrify audiences with the gory details. It's probably not a coincidence then that Radcliffe published The Italian - her own story of a depraved clergyman who terrorizes a young woman - shortly after the release of The Monk. Even though I once swore off any more Radcliffe, I'm curious now to read and compare The Monk and The Italian.

I haven't read The Monk, but I have seen the 2011 film adaptation by director Dominik Moll, starring Vincent Cassel as Ambrosio. It's been a few years since I've seen it, but my memory is that it's a fairly faithful, if heavily abridged version of the novel's plot. I found it challenging, both in terms of artistic style and content, but I also loved it as a cautionary tale against giving in to selfish passions. I'm hoping to have the same reaction to Lewis' novel.

Published on October 04, 2016 04:00

October 3, 2016

31 Days of Gothic Romance | The Mysteries of Udolpho

Horace Walpole may have officially started the gothic romance genre with The Castle of Otranto, but it was Ann Radcliffe who popularized it 30 years later with The Mysteries of Udolpho. It wasn't her first gothic romance, nor her last, but it was her most famous. And with her other books, Udolpho turned gothic romance into a genre that people could take seriously.

Part of how she did that was Scooby Dooing the supernatural elements. Her novels are full of supposedly haunted castles and cottages and abbeys, but there's always some kind of rational explanation for the spookiness. That gives her stories the thrill of genre books, but with the deniability that they're not really genre books. Literature Snobs are not a new phenomenon.

The other thing she did was include large sections of poetry and travelogue-like descriptions of landscapes. This was really well-received and Radcliffe inspired other writers as diverse and important as Walter Scott and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. However, it does make her kind of slog for modern readers. At least, it did for this modern reader.

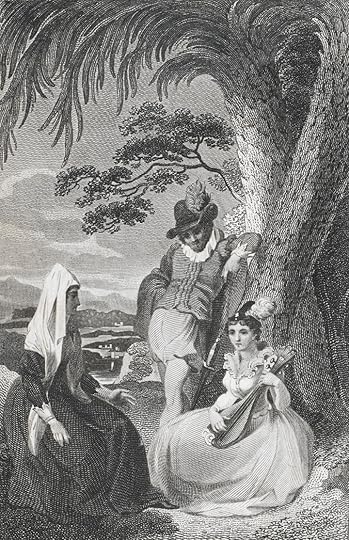

Hanging out. Talking about nature.Udolpho is the story a young woman named Emily St Aubert, whose father passes away and leaves her in the care of her aunt. Before this happens, she takes trips with Dad and they look at a lot of nature and talk about nature and at some point meet a handsome, nature-loving man who'll become important later. Oh, and Emily's mom also died and Emily lost a locket. There's a lot of setup in this thing.

Hanging out. Talking about nature.Udolpho is the story a young woman named Emily St Aubert, whose father passes away and leaves her in the care of her aunt. Before this happens, she takes trips with Dad and they look at a lot of nature and talk about nature and at some point meet a handsome, nature-loving man who'll become important later. Oh, and Emily's mom also died and Emily lost a locket. There's a lot of setup in this thing.Unfortunately, Emily's Aunt Cheron doesn't really like nature or looking at nature or talking about nature, so she and Emily don't get along. Worse than that, Madame Cheron is a gold-digger and marries a mysterious guy named Montoni who claims to be Italian nobility. But Montoni is actually broke and also looking for a way to make a quick buck. He's got his eye on marrying Emily to a different nobleman to hook into that money, but when Montoni learns that there's no fortune to be had there either, he retreats with the women to his remote castle of Udolpho to figure out a new plan.

What he comes up with is to try to force Madame Cheron in signing over some property to him. And while he's working on that (by imprisoning her in a tower of the castle), Emily has time to investigate various Mysteries of Udolpho. It gets more complicated from there, with Emily's discovering another prisoner in the castle and eventually escaping with him. I'm skipping a lot of stuff about secret portraits and locked doors, but that's to keep from having to also talk about Italian politics and extended trips to the countryside that also take place around that same time.

Emily meets some forest bandits.And we're not done once she leaves either. After that, she meets some friends of her fellow escapee and uncovers a whole other set of mysteries at their house. Except that they're actually tied into Udolpho and this convent that Emily and her dad stayed at one time and whatever happened to that handsome, nature-loving guy from earlier?

Emily meets some forest bandits.And we're not done once she leaves either. After that, she meets some friends of her fellow escapee and uncovers a whole other set of mysteries at their house. Except that they're actually tied into Udolpho and this convent that Emily and her dad stayed at one time and whatever happened to that handsome, nature-loving guy from earlier?Udolpho is the only Radcliffe novel I've read, and for years I claimed that it would be my last. I had to force myself through its 700 pages, enjoying the parts where the plot actually moves, but hating the long passages of unnecessary backstory and details about scenery. I think I might need to give it another chance, though. From a different point of view, what I thought was endlessly dull could also be described as luxuriously immersive. Radcliffe invites requires you to spend a lot of time in her story with her characters and you can either begrudge that or give in to it. I made my choice at the time. I wonder if it's possible to go back and do it the other way.

I don't know that I'll revisit Udolpho soon, but I'm easing back from my decision to not read any more of Radcliffe's stuff. I'll talk a little about The Italian tomorrow, a book of hers that I put on my To Read list at the same time as Udolpho and have since taken off. I might need to give that one a shot, with the foreknowledge that it won't be as face-paced or thrill-filled as The Castle of Otranto.

Whaaaat?!

Whaaaat?!

Published on October 03, 2016 04:00

October 2, 2016

31 Days of Gothic Romance | The Castle of Otranto

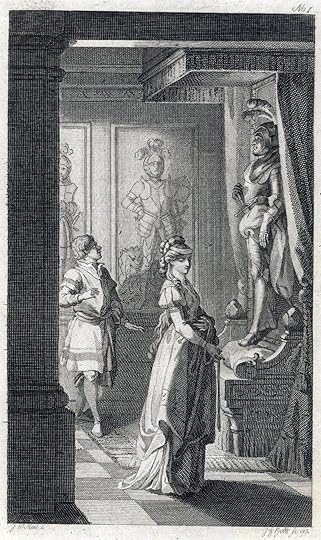

Horace Walpole's 1764 novel, The Castle of Otranto is generally accepted as the first, true gothic romance novel. As I mentioned yesterday though, the elements that make up the genre were not only present by Walpole's time, they'd already been arranged into a recognizably gothic story. And not just Beauty and the Beast, either. Otranto, with its crumbling, haunted castle, owes as much to Hamlet as any fairy tale. If beleaguered beauties and malevolent marquises are primary archetypes in a lot of gothic stories, then the common theme that drives those tales is decay. Particularly the decay of some once-great civilization or place like Shakespeare's Elsinore or the cursed castle of Beauty's Beast. Like those, Walpole's castle may be grand, but it's also threatened and tormented by the sins of its current master, Manfred.

Walpole was fascinated with medieval history and wanted to create a story that took place in it. In fact, it's the references to medieval architecture and setting that give gothic literature its name. But more than just using the scenery, Walpole wanted to write something that married medieval literature with the modern sensibilities of his day. He combined the fantastical elements of medieval epics and poetry with the realism that was popular in eighteenth century novels. He used the device - repeated many times in countless works since; most recently in the trend of found-footage movies - of claiming to have uncovered an old story that he had edited and was now presenting to the public. The people and places in Otranto are offered as real and historical, not legends and fairy tales. Walpole's innovation is that they also happen to share their world with the supernatural.

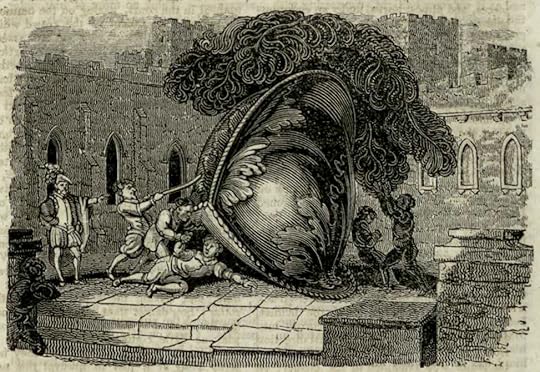

Manfred's wickedness has so angered the spirit world that they murder his only heir (with a giant helmet) and begin to haunt his castle. But that's mostly dressing on the real story, which is about the deplorable lengths that Manfred will go to in order to get a new heir, and how those actions affect his family. Manfred of course is the nefarious noble of the story who persecutes a couple of young heroines: his dead son's fiancée Isabella (whom Manfred now wants to take as his own wife, even though Manfred is already married) and Manfred's daughter Matilda (whom Manfred is willing to trade to Isabella's father in exchange for Isabella). There's also a young hero - beloved by both girls - who fights to put everything right again. Unlike Beauty and the Beast, it does take a man to rescue these women.

In spite of that though, The Castle of Otranto is a book that I've read and reread. It's a short novel (my copy has 110 pages), so even though the prose style is ancient, it moves quickly. There's plenty of drama, some great twists, and it's super atmospheric. It may not have been the first to collect the elements of the gothic romance genre into one story, but it certainly popularized them and inspired other writers to explore them as well. Some of whom we'll start looking at tomorrow...

Published on October 02, 2016 04:00

October 1, 2016

31 Days of Gothic Romance | Beauty and the Beast

Jean Marais and Josette Day in Jean Cocteau's La Belle et la Bête (1946)If I was any kind of blogger, I would have picked gothic romance as my Halloween countdown for last year. Tie it in with Crimson Peak. The thing is though that it took Crimson Peak to remind me how much I love the genre. And I've been thinking about it all year.

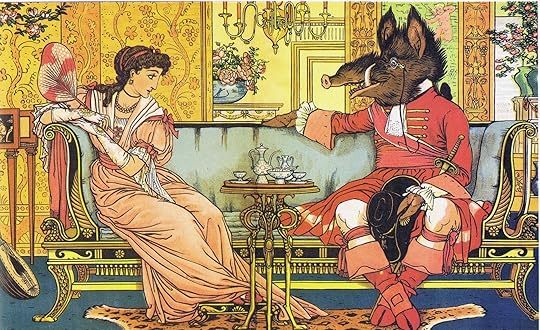

Jean Marais and Josette Day in Jean Cocteau's La Belle et la Bête (1946)If I was any kind of blogger, I would have picked gothic romance as my Halloween countdown for last year. Tie it in with Crimson Peak. The thing is though that it took Crimson Peak to remind me how much I love the genre. And I've been thinking about it all year.Tomorrow we'll get into the story that's generally acknowledged to have founded the genre, but all of my favorite tropes of gothic romance are present in Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve's Beauty and the Beast, published in 1740, a couple of decades before The Castle of Otranto. It's all about an innocent, young woman who's taken to a secluded castle against her will and lorded over by a sinister nobleman. That's the premise of all the best gothic romances, though there are many variations, especially around how the young woman escapes her predicament.

Beauty and the Beast has my favorite way though. A lot of gothic romances include a handsome, young, male hero who saves the woman from her malevolent master, but Beauty and the Beast lets her escape on her own. Or more accurately, choose not to escape by falling in love with the beast. Which is why I love the story so much.

George C Scott and Trish Van Devere in Beauty and the Beast (1976)I think my first exposure to the story must have been the 1976 TV movie starring Trish Van Devere as Belle and her husband George C Scott as the Beast. At first it was just an interesting, cool, spooky, fairy tale, but by the end I was extremely touched that Belle fell in love with the monster. As a clumsy, nerdy kid who didn't think much of his looks and imagined that he was of zero interest to girls, this gave me hope. Maybe one day, I also would meet a beautiful girl who would look past my imperfections. (The only problem with the story is the way it ends, which undercuts Belle's sacrificial declaration of love by giving her a handsome husband, but her love and willingness to sacrifice are still there, so I try to overlook that the story doesn't entirely stick the landing.)

George C Scott and Trish Van Devere in Beauty and the Beast (1976)I think my first exposure to the story must have been the 1976 TV movie starring Trish Van Devere as Belle and her husband George C Scott as the Beast. At first it was just an interesting, cool, spooky, fairy tale, but by the end I was extremely touched that Belle fell in love with the monster. As a clumsy, nerdy kid who didn't think much of his looks and imagined that he was of zero interest to girls, this gave me hope. Maybe one day, I also would meet a beautiful girl who would look past my imperfections. (The only problem with the story is the way it ends, which undercuts Belle's sacrificial declaration of love by giving her a handsome husband, but her love and willingness to sacrifice are still there, so I try to overlook that the story doesn't entirely stick the landing.)The Misunderstood Monster archetype became a powerful role model for me and explains my affection for characters from Frankenstein's Monster to Chewbacca. But it all started with the Beast and I've loved pretty much every iteration of the story I've ever seen. And my attachment to that story with it's spooky castle, monstrous noble, and heroic girl apparently also created a desire to see still other variations. And my love of gothic romance was born.

Anonymous (1813)

Anonymous (1813)

Walter Crane (1874)

Walter Crane (1874)

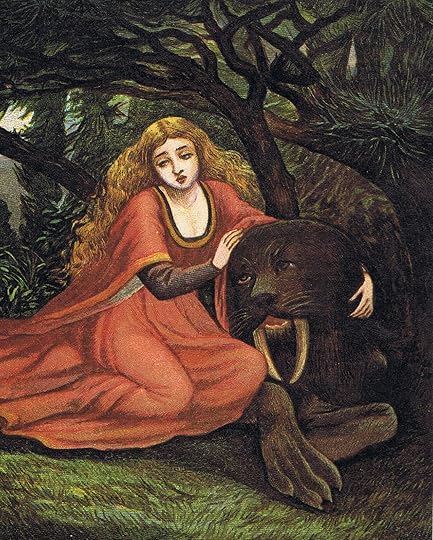

Eleanor Vere Boyle (1875)

Eleanor Vere Boyle (1875)

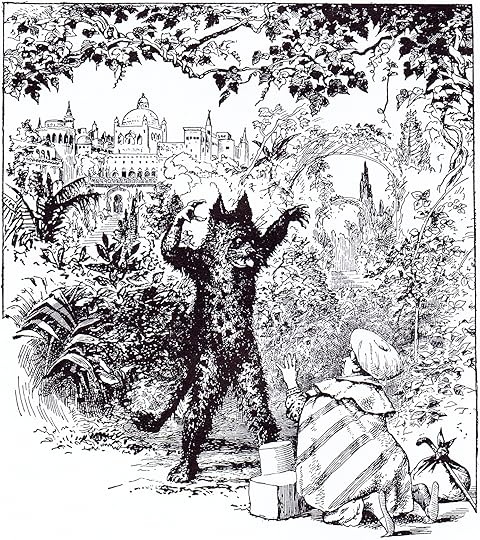

Lancelot Speed (1913)

Lancelot Speed (1913)

Linda Hamilton and Ron Perlman in the Beauty and the Beast TV series (1987-1990)

Linda Hamilton and Ron Perlman in the Beauty and the Beast TV series (1987-1990)

Disney's Beauty and the Beast (1991)

Disney's Beauty and the Beast (1991)

Vincent Cassel and Léa Seydoux in La Belle et la Bête (2014)The drawings above were all taken from this excellent article on Black and White: Words and Pictures about artistic interpretations of the Beast. Even more in that link.

Vincent Cassel and Léa Seydoux in La Belle et la Bête (2014)The drawings above were all taken from this excellent article on Black and White: Words and Pictures about artistic interpretations of the Beast. Even more in that link.

Published on October 01, 2016 04:00

September 30, 2016

Myself in Three Fictional Characters

Tomorrow's October, which means that this blog is going to turn towards Halloween and if I'm going to do that Three Fictional Characters meme, I'd better do it today.

Published on September 30, 2016 04:00

September 27, 2016

Starmageddon: Star Trek Continues and Fan Film Guidelines revisited

On the latest episode of Starmageddon, Dan, Ron, and I discuss the two latest Star Trek Continues episodes and come clean about our expectations for Rogue One. Then, related to Star Trek Continues, I talk to my pal and fellow Nerd Lunch Fourth Chairperson, Evan Hanson about the Star Trek fan-film guidelines. That's the second time the guidelines have been discussed on the show, but the first time with an actual lawyer and Evan has a great take on it.

Published on September 27, 2016 04:00

September 23, 2016

Mystery Movie Night: Dragon Wars, Last Airbender, and Dog Days

It's a big episode because we had a lot to say. David, Dave, and I are joined by pal Noel from the Masters of Carpentry podcast to discuss Hyung-rae Shim's Dragon Wars, M Night Shyamalan's The Last Airbender, and the third entry in the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series. Two of those are usually maligned, but our thoughts on them may surprise you. As will the secret connection that ties all three films together.

Published on September 23, 2016 04:00

September 21, 2016

Shooting Star: Murder from the Moon [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

Robert BlochRobert Bloch holds an unusual position in genre fiction in that he wrote for both the science fiction and mystery magazines equally well. (Fredric Brown and Anthony Boucher also come to mind.) This odd fusion finds the author writing SF mysteries as well as mysteries with a tinge of SF. Let’s look at two stories in question: “Murder From the Moon” (Amazing Stories, November 1942) and the Ace Double Noir novel, Shooting Star (1958).

Robert BlochRobert Bloch holds an unusual position in genre fiction in that he wrote for both the science fiction and mystery magazines equally well. (Fredric Brown and Anthony Boucher also come to mind.) This odd fusion finds the author writing SF mysteries as well as mysteries with a tinge of SF. Let’s look at two stories in question: “Murder From the Moon” (Amazing Stories, November 1942) and the Ace Double Noir novel, Shooting Star (1958).

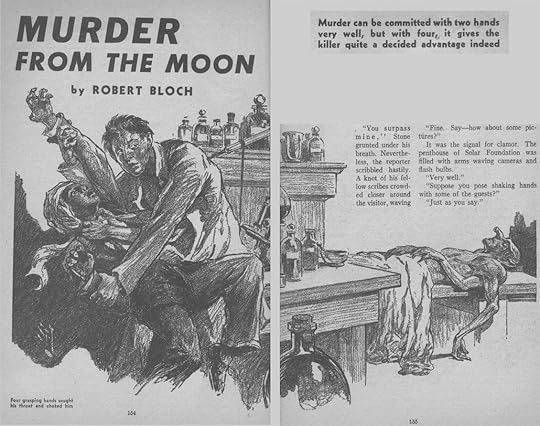

I’ve written before about Isaac Asimov’s complaint that SF mysteries prior to his Caves of Steel (1954) were of poor quality because they don’t play fair. The author hides some element the reader could not know or simply pulls out the SF equivalent of a magic wand and solves the case. I suppose that includes “Murder From the Moon” (along with Edmond Hamilton’s “Murder in the Void,” Robert Leslie Bellem’s “Robots Can’t Lie,” Mickey Spillane’s “The Veiled Lady,” and others). Bloch is in good company. Let’s see if Asimov is correct.

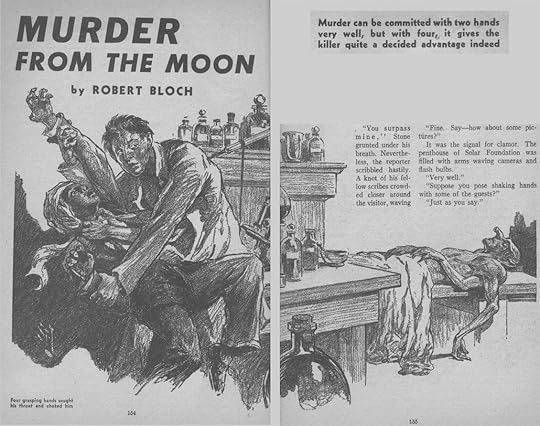

“Murder From the Moon” centers around the visit of a man from our satellite, and the long-standing feud between Stephen Bennet and Professor Champion. Avery Bennet, Stephen’s father, had gone to the Moon and made claims of alien life, which Champion denied. Avery Bennet left on a second expedition but never returned. With the visitor’s coming, it looks like vindication is at hand. After a publicity photo with four scientists shaking all of the moon man’s multiple hands, the Lunarian says he is cold. Someone gets the Lunarian a cup of hot chocolate. He drops dead, crying, “Cold, so cold!” Bill Stone, a reporter, wants to tell the world, but is persuaded to hold on and solve the mystery.

While an investigation is begun we learn more about Stephen Bennet, his Solar Foundation, Lila Valery (Bennet’s girlfriend), and his life-long servant, Changara Dass (a cliché Hindu valet right out of Aurelius Smith). Dass manages the foundation, keeping the environment at a steady 80 degrees Farenheit. We hear that Bennet lives at the foundation like a recluse, for he was born in space and after the ridicule of his father’s memory, feels no warmth for his fellow humans.

While an investigation is begun we learn more about Stephen Bennet, his Solar Foundation, Lila Valery (Bennet’s girlfriend), and his life-long servant, Changara Dass (a cliché Hindu valet right out of Aurelius Smith). Dass manages the foundation, keeping the environment at a steady 80 degrees Farenheit. We hear that Bennet lives at the foundation like a recluse, for he was born in space and after the ridicule of his father’s memory, feels no warmth for his fellow humans.

An autopsy is performed on the dead Lunarian by Changara Dass. He calls everyone together because he has made an important discovery, but when they arrive they find him strangled to death. The marks on his throat indicate it was done by a moon man, but the visitor is clearly dead, his arm having been cut off. Bill Stone investigates the crime scene, knowing that when the police arrive his access to the evidence will be limited. He finds a single clue, a cup containing something very cold. He has solved the mystery.

Next Stone gets Stephen Bennet alone, so he can question him. The man most likely to suppress the moon visit, the obvious suspect, is Dr. Champion. But the killer turns out to be Stephen Bennet, who wants to sneak off with his girl and take the alien’s ship back to the Moon. Stone accuses Bennet of the two murders. Bennet begins to wrestles with the reporter. While his hands are locked in battle, a second set of hands reveal themselves and clutch Bill Stone’s throat – clawed Lunarian hands! Stone defeats and kills Bennet with the cup of coldness, ordinary dry ice. After Bennet dies, the reporter explains to Lila that the man born in space was half Lunarian and his secret would have been revealed by the visitor. Bennet had spiked the hot chocolate with dry ice to kill him. Dass was killed because he was about to reveal Bennet’s secret. The killer secretly planned to take Lila to the Moon where he would rule over his Lunarian brethen like a king.

Isaac Asimov’s complaint was that science fiction mysteries did not play fair. And I think Robert Bloch’s story should be included amongst these types of stories. If we knew all the facts about Lunarians, we would have figured out the killer pretty quick. In an Asimovian SF mystery, we would know all about the Lunarians, their physiology and such, and still would not know who the killer was. Bloch has not done this, though I don’t think he particularly cared in this case. He wasn’t writing for Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, but for Ray Palmer’s Amazing Stories. Bloch certainly was able to follow the rules as he did in novels like The Scarf (1947) and in the 1950s and 1960s stories for EQMM.

Isaac Asimov’s complaint was that science fiction mysteries did not play fair. And I think Robert Bloch’s story should be included amongst these types of stories. If we knew all the facts about Lunarians, we would have figured out the killer pretty quick. In an Asimovian SF mystery, we would know all about the Lunarians, their physiology and such, and still would not know who the killer was. Bloch has not done this, though I don’t think he particularly cared in this case. He wasn’t writing for Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, but for Ray Palmer’s Amazing Stories. Bloch certainly was able to follow the rules as he did in novels like The Scarf (1947) and in the 1950s and 1960s stories for EQMM.

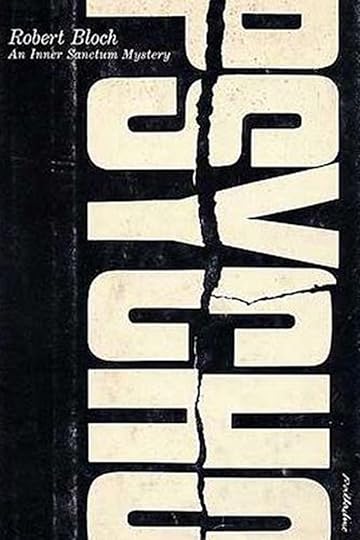

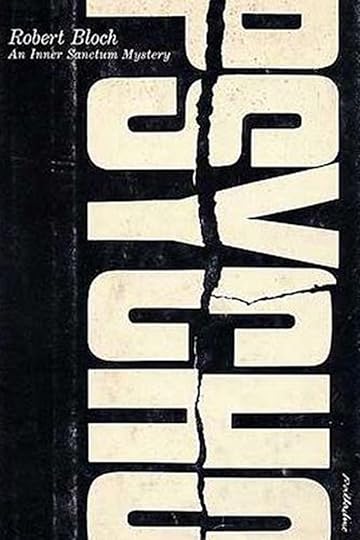

Instead, Bloch is interested in “the reveal” – as he would be in his most famous work, Psycho (1959), when we learn Norman Bates is really the voice of his dead, cruel mother. The pay off is sensation – not a logical puzzle. The reveal that Stephen Bennet has a second set of arms is meant to be the pay off, as a horror writer might do it. (A possible inspiration for the idea is Clifford Ball’s “Thief of Forthe” (Weird Tales, July 1937), in which the wizard Karlk escapes from being tied up because he has a second set of weird arms. Bloch was certainly familiar with the story as his tale “The Creeper in the Crypt” is in the same issue. Bloch’s use of the idea is much more dramatic, being part of a fight scene.

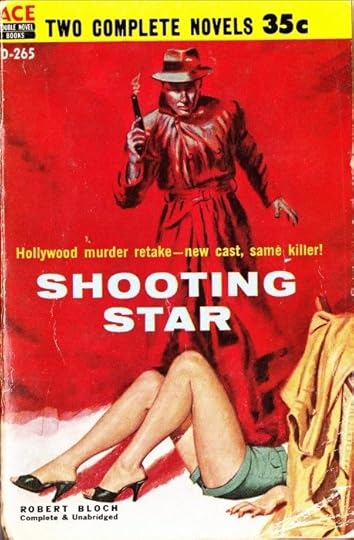

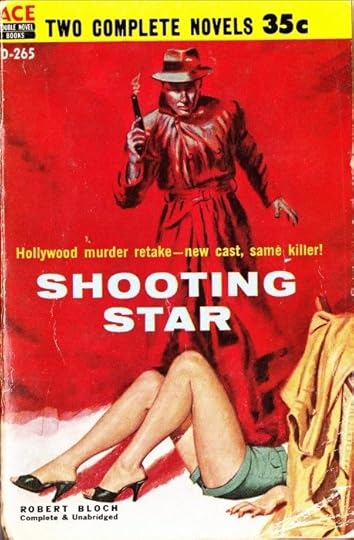

I mention Shooting Star here merely as a delicious aside. It has no science fiction ideas in it, nor is it placed at an SF convention like Anthony Boucher’s Rocket to the Morgue (1942). Instead, Bloch peppers it with references from the world of SF. The main character is a one-eyed literary agent, Mark Clayburn. He begins his day:

I mention Shooting Star here merely as a delicious aside. It has no science fiction ideas in it, nor is it placed at an SF convention like Anthony Boucher’s Rocket to the Morgue (1942). Instead, Bloch peppers it with references from the world of SF. The main character is a one-eyed literary agent, Mark Clayburn. He begins his day:

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Robert BlochRobert Bloch holds an unusual position in genre fiction in that he wrote for both the science fiction and mystery magazines equally well. (Fredric Brown and Anthony Boucher also come to mind.) This odd fusion finds the author writing SF mysteries as well as mysteries with a tinge of SF. Let’s look at two stories in question: “Murder From the Moon” (Amazing Stories, November 1942) and the Ace Double Noir novel, Shooting Star (1958).

Robert BlochRobert Bloch holds an unusual position in genre fiction in that he wrote for both the science fiction and mystery magazines equally well. (Fredric Brown and Anthony Boucher also come to mind.) This odd fusion finds the author writing SF mysteries as well as mysteries with a tinge of SF. Let’s look at two stories in question: “Murder From the Moon” (Amazing Stories, November 1942) and the Ace Double Noir novel, Shooting Star (1958).I’ve written before about Isaac Asimov’s complaint that SF mysteries prior to his Caves of Steel (1954) were of poor quality because they don’t play fair. The author hides some element the reader could not know or simply pulls out the SF equivalent of a magic wand and solves the case. I suppose that includes “Murder From the Moon” (along with Edmond Hamilton’s “Murder in the Void,” Robert Leslie Bellem’s “Robots Can’t Lie,” Mickey Spillane’s “The Veiled Lady,” and others). Bloch is in good company. Let’s see if Asimov is correct.

“Murder From the Moon” centers around the visit of a man from our satellite, and the long-standing feud between Stephen Bennet and Professor Champion. Avery Bennet, Stephen’s father, had gone to the Moon and made claims of alien life, which Champion denied. Avery Bennet left on a second expedition but never returned. With the visitor’s coming, it looks like vindication is at hand. After a publicity photo with four scientists shaking all of the moon man’s multiple hands, the Lunarian says he is cold. Someone gets the Lunarian a cup of hot chocolate. He drops dead, crying, “Cold, so cold!” Bill Stone, a reporter, wants to tell the world, but is persuaded to hold on and solve the mystery.

While an investigation is begun we learn more about Stephen Bennet, his Solar Foundation, Lila Valery (Bennet’s girlfriend), and his life-long servant, Changara Dass (a cliché Hindu valet right out of Aurelius Smith). Dass manages the foundation, keeping the environment at a steady 80 degrees Farenheit. We hear that Bennet lives at the foundation like a recluse, for he was born in space and after the ridicule of his father’s memory, feels no warmth for his fellow humans.

While an investigation is begun we learn more about Stephen Bennet, his Solar Foundation, Lila Valery (Bennet’s girlfriend), and his life-long servant, Changara Dass (a cliché Hindu valet right out of Aurelius Smith). Dass manages the foundation, keeping the environment at a steady 80 degrees Farenheit. We hear that Bennet lives at the foundation like a recluse, for he was born in space and after the ridicule of his father’s memory, feels no warmth for his fellow humans.An autopsy is performed on the dead Lunarian by Changara Dass. He calls everyone together because he has made an important discovery, but when they arrive they find him strangled to death. The marks on his throat indicate it was done by a moon man, but the visitor is clearly dead, his arm having been cut off. Bill Stone investigates the crime scene, knowing that when the police arrive his access to the evidence will be limited. He finds a single clue, a cup containing something very cold. He has solved the mystery.

Next Stone gets Stephen Bennet alone, so he can question him. The man most likely to suppress the moon visit, the obvious suspect, is Dr. Champion. But the killer turns out to be Stephen Bennet, who wants to sneak off with his girl and take the alien’s ship back to the Moon. Stone accuses Bennet of the two murders. Bennet begins to wrestles with the reporter. While his hands are locked in battle, a second set of hands reveal themselves and clutch Bill Stone’s throat – clawed Lunarian hands! Stone defeats and kills Bennet with the cup of coldness, ordinary dry ice. After Bennet dies, the reporter explains to Lila that the man born in space was half Lunarian and his secret would have been revealed by the visitor. Bennet had spiked the hot chocolate with dry ice to kill him. Dass was killed because he was about to reveal Bennet’s secret. The killer secretly planned to take Lila to the Moon where he would rule over his Lunarian brethen like a king.

Isaac Asimov’s complaint was that science fiction mysteries did not play fair. And I think Robert Bloch’s story should be included amongst these types of stories. If we knew all the facts about Lunarians, we would have figured out the killer pretty quick. In an Asimovian SF mystery, we would know all about the Lunarians, their physiology and such, and still would not know who the killer was. Bloch has not done this, though I don’t think he particularly cared in this case. He wasn’t writing for Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, but for Ray Palmer’s Amazing Stories. Bloch certainly was able to follow the rules as he did in novels like The Scarf (1947) and in the 1950s and 1960s stories for EQMM.

Isaac Asimov’s complaint was that science fiction mysteries did not play fair. And I think Robert Bloch’s story should be included amongst these types of stories. If we knew all the facts about Lunarians, we would have figured out the killer pretty quick. In an Asimovian SF mystery, we would know all about the Lunarians, their physiology and such, and still would not know who the killer was. Bloch has not done this, though I don’t think he particularly cared in this case. He wasn’t writing for Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, but for Ray Palmer’s Amazing Stories. Bloch certainly was able to follow the rules as he did in novels like The Scarf (1947) and in the 1950s and 1960s stories for EQMM.Instead, Bloch is interested in “the reveal” – as he would be in his most famous work, Psycho (1959), when we learn Norman Bates is really the voice of his dead, cruel mother. The pay off is sensation – not a logical puzzle. The reveal that Stephen Bennet has a second set of arms is meant to be the pay off, as a horror writer might do it. (A possible inspiration for the idea is Clifford Ball’s “Thief of Forthe” (Weird Tales, July 1937), in which the wizard Karlk escapes from being tied up because he has a second set of weird arms. Bloch was certainly familiar with the story as his tale “The Creeper in the Crypt” is in the same issue. Bloch’s use of the idea is much more dramatic, being part of a fight scene.

I mention Shooting Star here merely as a delicious aside. It has no science fiction ideas in it, nor is it placed at an SF convention like Anthony Boucher’s Rocket to the Morgue (1942). Instead, Bloch peppers it with references from the world of SF. The main character is a one-eyed literary agent, Mark Clayburn. He begins his day:

I mention Shooting Star here merely as a delicious aside. It has no science fiction ideas in it, nor is it placed at an SF convention like Anthony Boucher’s Rocket to the Morgue (1942). Instead, Bloch peppers it with references from the world of SF. The main character is a one-eyed literary agent, Mark Clayburn. He begins his day:I went over to the desk and sat down. This was no time to feel sorry for myself. Save that for tonight. Right now I had work to do: a science-fiction yarn to send to Boucher, for a client; another to try on a confessions mag, and a true-detective job to revise.The plot and style of the novel is pulp noir with Clayburn investigating the murder of a film star for an old friend who has bought up the cowboy star’s run of old Westerns. Later, when another actor is murdered, the undertaker is named Hamilton Brackett. He could have been named anything but Bloch is leaving a treat for two dear friends, the husband and wife team of SF writers, Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett. None of this comes close to a SF mystery, but it is great for fans of both genres. Bloch’s personal insight into Hollywood, agents, and the writing game are all spice to what is a decent mystery. This is why Hardcase Crime have reprinted it along with Spiderweb, another short novel, as part of their noir series.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on September 21, 2016 04:00

September 20, 2016

Hellbent for Letterbox: The Magnificent Seven (1960)

Pax and I get ready for the upcoming Magnificent Seven remake by sitting down with the original starring Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughn, James Coburn, Brad Dexter, Horst Buchholz, and Eli Wallach.

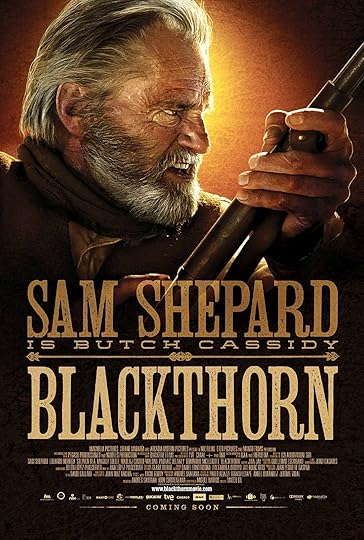

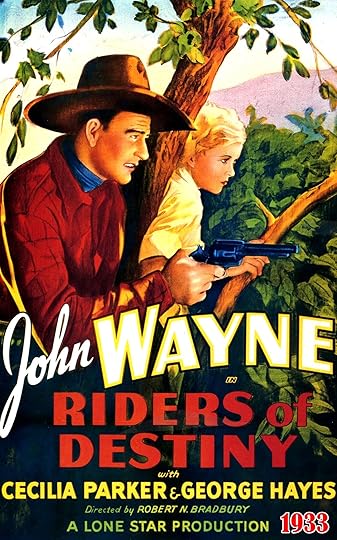

We also revisit DC's Justice Riders, talk over Chuck Dixon and John Buscema's Punisher: A Man Named Frank, discuss Sam Shepard as Butch Cassidy in Blackthorn, follow up on Bo Hampton's 3 Devils, converse on Kid Colt Outlaw #171 (guest-starring the Two-Gun Kid), and gab about early John Wayne movies Sagebrush Trail and Riders of Destiny.

Published on September 20, 2016 04:00

September 19, 2016

Hellbent for Letterbox: Yojimbo (1961) and Dollar for the Dead (1998)

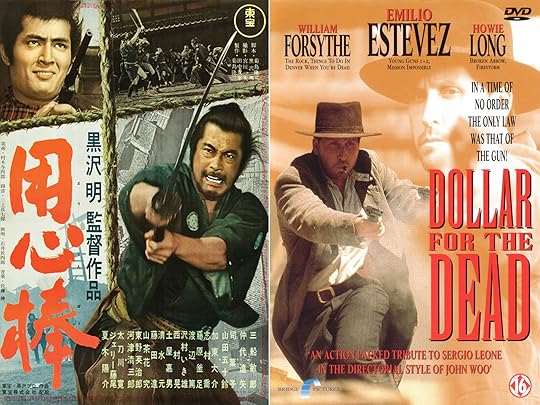

In this special Hitchin' Post episode, Pax and I look into Sergio Leone's influences. First, we discuss the 1961 samurai classic Yojimbo by Akira Kurosawa, which inspired A Fistful of Dollars. Then we also take a look at the 1998 TV movie Dollar for the Dead starring Emilio Estevez, which Leone's Dollars Trilogy in turn inspired.

Published on September 19, 2016 04:00