Rick Schindler's Blog

August 19, 2018

‘Pnin’ by Vladimir Nabokov: Satire with sadness

Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov

Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

One day when I was very young, my father extracted from some hidden recess of our basement a stack of paperback books. Though still years away from puberty, I could tell some were a bit louche, both from the luridness of the covers and the way my father was trying to shoo me away from them.

By the priggish standards of Catholic-dominated mid-century Buffalo, such authors as William Faulkner, Erskine Caldwell and James T. Farrell were considered virtual pornographers. Canny publishers stoked their bad reputations by plastering racy covers onto paperback editions of such novels as Faulkner’s Pylon, Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre and Farrell’s Studs Lonigan trilogy, all of which turned up in my house when I was a child. Due to such efforts, heterosexual males of the Mad Men era in search of a prurient tingle or two were probably exposed against their will to some pretty good American literature.

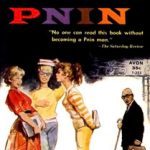

The cover I remember best among my father’s covert collection was that of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin. It caught my eye both with its odd title and its vivid illustration of three saucy young women eyed from afar by a little bald man. So distinctly did I recollect it that it took me less than a minute to find it online. A blurb above the title evokes the most notoriously naughty novel of the era, Nabokov’s Lolita.

The cover I remember best among my father’s covert collection was that of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin. It caught my eye both with its odd title and its vivid illustration of three saucy young women eyed from afar by a little bald man. So distinctly did I recollect it that it took me less than a minute to find it online. A blurb above the title evokes the most notoriously naughty novel of the era, Nabokov’s Lolita.

Though the cover is technically not inaccurate, it is highly selective: Only late in the book comes one brief reference to “Pnin ogling a coed.” That is buried deep inside a

wicked (but not very sexy) Horatian satire of academia (specifically Cornell, where Nabokov taught) as well as a poignantly comic portrait of Timofey Pavlovich Pnin, a gentle, scholarly Russian expatriate haunted by memories of his lost homeland and lost loves, rendered in exquisite if often idiosyncratic prose.

My father must have been quite disappointed. More than half a century later, I am not.

July 31, 2018

Review: ‘The Secret History of Wonder Woman’ revealed

The Secret History of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore

The Secret History of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

The Secret History of Wonder Woman can’t be judged by its cover. Adorned with a vintage-style illustration of its subject discarding her civilian togs to reveal her superheroine bustier underneath, it could be mistaken for a lighthearted pop culture book, or even a graphic novel.

Instead, Jill Lepore’s book is a meticulous and scholarly history of not only the most iconic female character in comic bookdom, but also of American feminism, the invention of the polygraph, the development of psychology as an academic discipline, and more.

But just because the book is carefully researched doesn’t mean it’s dry and dull. It’s not, because more than anything else, The Secret History of Wonder Woman is the story of her creator, William Moulton Marston: half genius, half huckster, a bigger-than-life American original whose real life was as outrageous (and as kinky) as the comic-book adventures he wrote.

A Phi Beta Kappa Harvard graduate who went on to a checkered career as an academic, lawyer and pop psychologist, Marston devised the earliest version of the lie detector (which appears in his comics in the guise of Wonder Woman’s Lasso of Truth). As his academic career foundered, he inveigled his way into Hollywood as a psychological consultant on movie scripts, and eventually found his destiny in the fledgling comic book industry by creating a female answer to Superman — a potent (and instantly popular) mix of pin-up girl and feminist icon, a beautiful and powerful Amazon princess out to inspire the world to abandon the folly of war for a benevolent utopian gynarchy.

Marston’s feminist idealism was sincere, but also paradoxical: He believed that violent male nature needed to be put in check by what he regarded as the feminine virtue of submissive love. That paradox is represented in his comic books by Wonder Woman’s “bracelets of submission,” which, if chained together by a man, cause her to lose her mighty powers.

In fact, Marston’s Wonder Woman stories are rife with bondage – she and other female characters are constantly getting captured, tied up, chained, enslaved and even spanked. To young readers it came across as innocent cowboy-style action, but the fetishism was not lost on adult fans with similar proclivities, nor on Marston’s editors and critics.

But what no one suspected was the secret of Marston’s personal life: that he lived in a ménage à trois with his wife and fellow psychologist Elizabeth Holloway Marston, who had helped him develop his prototype lie detector, and his former research assistant Olive Byrne (who, not coincidentally, frequently wore bracelets similar to Wonder Woman’s), niece of birth-control activist Margaret Sanger. Two of Marston’s four children (two with Elizabeth, two with Olive) were raised in the same household without even knowing he was their father.

Thus Lepore’s book becomes a detective story as well as 20th-century history, as she interviews witnesses and assembles clues to uncover the truth about a colorful and remarkable life. And she did it all without a lie detector or a Lasso of Truth.

November 4, 2017

Beware the monster bear: ‘Borne’ by Jeff VanderMeer

Borne by Jeff VanderMeer

Borne by Jeff VanderMeer

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Jeff VanderMeer is a poet of the postapocalypse. His Southern Reach trilogy (its first book, Annihilation, is becoming a movie starring Natalie Portman, helmed by “Ex Machina” director Alex Garland; its third, Acceptance, is reviewed by me here) is set in a wilderness where nature has turned monstrous and malevolent. His latest novel is an urban counterpart.

The ravaged cityscape of Borne makes Mad Max’s Fury Road look like the tonier blocks of Park Avenue. Buildings have been reduced to rubble, food and potable water are scarce, a poisoned river suppurates with pollution, and feral children prowl and pounce.

This fine kettle of synthetic fish has been brought to you by the wonderful folks at a defunct company referred to simply as the Company, who were none too careful cooking up artificial life and cleaning up after themselves, resulting in all manner of misshapen quasi-life forms crawling, shambling and otherwise infesting the vicinity. The largest of these is a monstrous, ursine creature called Mord that rules the ruined city like an angry god. We are talking about a bear as big as Godzilla, and not as nice. That flies.

Against this cataclysmic landscape is set the none-too-tender romance of Rachel the Scavenger, a young woman with sketchy memories of her parents and a world that used to be better before it descended into chaos, and Wick, who used to work for the Company and still cooks up his own biotech from Rachel’s pickings. In a collapsed apartment building they’ve fortified with false entrances and traps, they scrabble for survival and make desperate love.

One day, from a foray into the fur of the slumbering Mord, Rachel brings home Borne. At first Borne seems little more than a potted plant or a virtual pet, but he develops, and thereby hangs VanderMeer’s tale.

VanderMeer has a highly specific vision of horror that I surmise is rooted in his personal connection with nature. Out of his fecund imagination spring and slither monstrosities that would give Bosch and Lovecraft the heebie-jeebies.

But VanderMeer also has a knack for damaged but resourceful female protagonists in the tradition of Ellen Ripley of the Alien franchise. Borne succeeds both as cautionary science-fiction and a compelling survival thriller.

August 18, 2017

Review: Crossing to Safety by Wallace Stegner

There is drama in Wallace Stegner‘s Crossing to Safety, but it’s the drama of everyday life: career successes and disappointments; courtships and births and illnesses; a hiking trip gone awry. There’s little sex, or even suspense; because the novel is mostly flashback, we know most of what will happen to the protagonists from the get-go. Instead there are lyrical descriptions of nature and scholarly ruminations on poetry.

There is drama in Wallace Stegner‘s Crossing to Safety, but it’s the drama of everyday life: career successes and disappointments; courtships and births and illnesses; a hiking trip gone awry. There’s little sex, or even suspense; because the novel is mostly flashback, we know most of what will happen to the protagonists from the get-go. Instead there are lyrical descriptions of nature and scholarly ruminations on poetry.

So why is a leisurely paced novel about the decades-long relationship between two academic couples so compelling? Paradoxically, it’s the book’s particularity that makes it so relatable. All the characters are drawn vividly, but the four main ones we come to know so intimately that it’s impossible to avoid becoming invested in their destinies. And their actions flow so organically from their choices that we soon find ourselves nodding at them: yes, isn’t that just like Charity, or Sid, or Sally or the narrator, the promising author Larry.

But when we nod it’s also in recognition, not only because the years following the Great Recession may not be so very different from the ones following the Great Depression, but also because character traits like generosity and stubbornness are as manifest today as they were in the previous century. We know people like these; we are people like these.

And in coming to know them we come to know ourselves a little better too. Stegner has come to be known as a western writer, but that does him a disservice; he is a universal writer.

July 18, 2017

Review: Whiskey Tango Foxtrot by David Shafer

The Pacific Northwest seems to exert a natural gravity on iconoclastic novelists. Ken Kesey lived most of his life in Oregon and wrote what is arguably the iconic Oregon novel, Sometimes a Great Notion. Tom Robbins spent the majority of his adult life in Seattle. Richard Brautigan, born in Tacoma, would wind up in Eugene, Oregon, where a public sculpture of Kesey stands today. “Oregon is the citadel of the spirit,” Kesey once wrote.

The Pacific Northwest seems to exert a natural gravity on iconoclastic novelists. Ken Kesey lived most of his life in Oregon and wrote what is arguably the iconic Oregon novel, Sometimes a Great Notion. Tom Robbins spent the majority of his adult life in Seattle. Richard Brautigan, born in Tacoma, would wind up in Eugene, Oregon, where a public sculpture of Kesey stands today. “Oregon is the citadel of the spirit,” Kesey once wrote.

(Which is a nice way of saying what I found unavoidable in the three years I lived outside Portland: Oregonians typically take pride in dogged anti-authoritarianism.)

New York City-born Portland resident David Shafer’s debut novel continues that tradition with its three nonconformist protagonists: Leila Majnoun, a feisty Persian-American woman who becomes the Woman Who Saw Too Much while working for an international nonprofit in a remote corner of Myanmar; Leo Crane, a paranoic substance abuser spiraling downward in Portland, and Leo’s college buddy Mark Devereaux, now the self-despising author of a wildly successful self-help manual he doesn’t believe in himself.

There are echoes of Thomas Pynchon (especially his latest novel, Bleeding Edge) in the circumstance that makes the trio unlikely allies: a scheme to collect and monetize all the private information in the world. David Foster Wallace can be felt too, in a section set in a recovery community that recalls large portions of Infinite Jest.

But the Myanmar sections of Shafer’s book are my favorite; Leila is a sympathetic heroine and Shafer’s evocation of the exotic locale is vivid and convincing. Leo and Mark are also likable despite being far more flawed than Leila, but they are more alike than may be optimal in a novel with multiple third-person points of view: Sometimes they feel like two halves of the same character. There are also passages of dialogue that go on longer than may need to, convenient coincidences, and a rather pat romantic subplot.

But Whiskey Tango Foxtrot is also filled with clever conceits, and the issues it ambitiously tackles are highly topical. I think Ken Kesey would approve.

June 6, 2017

Review: Willnot by James Sallis

I am the opposite of a mystery fan. I have read the entire Sherlock Holmes canon end to end, and the main things that interested me were the relationship between Holmes and Watson and the tiny flashes of humanity in Holmes that seemed to occur only once every dozen stories or so. I tried some Agatha Christie and hated it, despite grudging admiration for the tortuous ingenuity of And Then There Were None. I once picked up a Maigret novel by Georges Simenon and all I got out of it was the moody Parisian atmosphere.

The trouble with mysteries and me is, I just don’t care who did it. Which makes James Sallis’s Willnot the right kind of mystery for me.

The title refers to a remote community of misfits, oddballs and stubborn individualists whose town doctor becomes embroiled in puzzling goings-on after the discovery of a mass grave. But in this story, the sleuth himself is an enigma: After a long, unexplained coma in childhood, Lamar Hale is beset by feverish dreams and out-of-body experiences that seem to propel him into other people’s bodies and future incidents.

The plot doesn’t so much unwind as lurch sideways, odd incidents punctuating quotidian routine, simulating the texture of life in a small, quirky town. The characters are colorful and engaging, and Sallis’ prose is spare and often poetically wistful.

If all you care about is who done it, you may leave Willnot unsatisfied. But if the vagaries of the human heart intrigue you, you’ll be glad you visited, and may want to go back.

June 1, 2017

Review: Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J.D. Vance

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J.D. Vance

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

When it came out in the middle of the feverish 2016 presidential campaign, J. D. Vance‘s Hillbilly Elegy was cannily marketed as insight into the mysterious mind of the Trump voter. That’s not wholly untrue, but its subtitle is a better description: “A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis.” To me the book is at heart a raw and honest look at a childhood that was, to employ a non-clinical term, a shit show.

Vance’s story hit me close to home. He and I both grew up in the Rust Belt. His grandparents were poor people from the Appalachia region of Kentucky who migrated to Ohio in search of a better life. My maternal grandfather was a second-generation Irish coal miner in eastern Pennsylvania’s Pocono Mountains, a subrange of the Appalachians, and my mother, one of his 10 children, migrated to Buffalo, New York, in search of opportunity. (Note: It was narrow victories in Ohio and Pennsylvania, along with Michigan, that put Trump in the White House.)

I was raised in middle-class comfort, and I romanticized my mom’s background (a few years ago I even did so professionally, editing and producing her blog of small-town American wisdom). It took Vance to make me realize the negative impact of her childhood poverty.

.

The book’s strength is Vance’s candor about his emotional scars; its weakness is the thin patina of sociology he paints over them. To my eye his much-touted dissection of the motivations of the Trump voter boils down to garden-variety class resentment. But as an evocative self-portrait of a man who overcame daunting impediments to graduate from Yale Law School and become a successful author and commentator at a young age, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis is a resounding success.

April 21, 2017

Review: His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

It’s no mean feat, pulling off a taut psychological murder mystery while confined to the tight box of fictional 19th-century documents, yet Graeme Macrae Burnet does it.

His antihero is 17-year-old Roderick Macrae, who has the soul of a poet and the misfortune to have been born in a literal dead end, a woebegone coastal farming village. Clearly Burnet has done thorough research; his finely detailed setting is more the star of his story than poor Roddy or any of his supporting cast of flat but colorful Dickensian characters.

The storytelling is confident, the pace brisk. The narrative unfolds with the inevitability of a Greek tragedy; we see everything coming and yet are compelled to see events through to the bitter end.

And yet… you know that sensation when you reach the top of a staircase and there’s one less step than you thought? That’s how I felt at the end of His Bloody Project. But I was still glad I’d made the climb.

April 11, 2017

Review: Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang

Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang

Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Writing about the album In Between by The Feelies, Rick Moody posits that rock ’n’ roll is in late middle age, its focus turned reflective and retrospective. I think much the same can be said of science fiction. Much as rock ’n’ roll has been supplanted by dance pop as the dominant popular music genre, SF has been pushed aside by fantasy. Roll over, Clarke, Heinlein, Bradbury, Asimov, et al.; hail, hail, J.K. Rowling and George R. R. Martin.

In Stories of Your Life and Others, a collection of stories from the ’90s and early 2000s, Ted Chiang looks back at classic science-fiction concepts and reworks them, as well jumping to and fro across the line between old-school SF and more fashionable fantasy. And for the most part, he performs this dance with brio and grace.

“Understand” is the most emblematic example of Chiang rummaging through SF’s attic for treasures: Within just a couple of pages I knew I was reading an homage to Daniel Keyes’ classic “Flowers for Algernon” (which was adapted into the Oscar-winning 1968 film Charly). Assuming I knew how the story would turn out, I was disappointed. But I was wrong: Chiang takes Keyes’ premise (a man turned into a super genius through artificial means) in new yet internally logical directions, while repeating Keyes’ coup of convincingly imagining the mental landscape of a mega-mastermind.

Similarly, “Story of Your Life,” which was adapted into the 2016 film Arrival (which I have not seen as of this writing, though I look forward to it), reworks a concept from a science-fiction classic. To specify which one might be enough to reveal the premise of the entire story, so I won’t. What I will say is that Chiang builds on that premise to craft the most satisfying story in this collection, a triumph both as stimulating speculative fiction and satisfying emotional narrative, as well as a fine example of a male writer successfully inhabiting a female protagonist.

“Liking What You See: A Documentary” also reworks a familiar idea: Though its narrative is a bit unconventional, soon enough it becomes apparent that Chiang is updating the theme of the classic Twilight Zone episode “Eye of the Beholder,” with uneven results.

Several other stories in the collection are set in alternative realities where magic or miracles are operative, a la Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. “Seventy-Two Letters” imagines the impact of the mass production of golems in 18th-century England, a clever conceit at the heart of a somewhat dull story. “Hell Is the Absence of God” is a bleak vision of a contemporary world where angels from heaven visit regularly, leaving miracles and destruction alike in their wake with utter indifference. And “Tower of Babylon,” my favorite of these three, vividly portrays the life of a miner in a mythological milieu.

It can’t be easy, writing science fiction in an era when wizards and comic-book superheroes rule the box office. Ted Chiang does it with ingenuity and deep intelligence.

March 22, 2017

Review: Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I am unembarrassed to join the chorus of praise for this complex yet lucid novel, which presents us with two fractured families linked by betrayal and tragedy and makes us forgive their sins. Surefooted as a mountain goat, Patchett leaps to and fro across 50 years of nonlinear narrative, carrying us along on prose as clear and bracing as an alpine spring.

In its strongest chapter, the novel carries us to a Buddhist retreat in Switzerland that evokes The Magic Mountain unmistakably. But while it conveys the nuance and detail of literature, Commonwealth continually radiates humor, compassion and humility.

The book’s title refers to Virginia, where its story begins, as well as to a novel within the novel, an ingenious conceit and the hinge of the plot. But it is also apt in another way: Though its idiom appears plain and ordinary, Commonwealth delivers a rich bounty of rewards.

Rick Schindler's Blog