Rick Schindler's Blog, page 4

May 28, 2014

The best things in life aren’t free: Thoughts on the mid-season finale of ‘Mad Men’

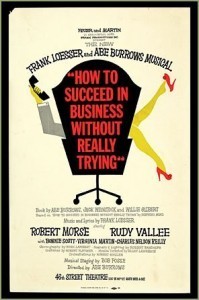

I always found it richly ironic that the actor behind the bohemian goatee of Bert Cooper, senior partner at Don Draper’s ad agency on Mad Men, was Robert Morse, whose signature role was J. Pierrepont Finch, hero of the musical comedy How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. But Morse has been so disciplined and deadpan in his performance as Cooper for the past seven years that he made it easy to forget how sly the casting was.

I always found it richly ironic that the actor behind the bohemian goatee of Bert Cooper, senior partner at Don Draper’s ad agency on Mad Men, was Robert Morse, whose signature role was J. Pierrepont Finch, hero of the musical comedy How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. But Morse has been so disciplined and deadpan in his performance as Cooper for the past seven years that he made it easy to forget how sly the casting was.

Until this past weekend, that is, when creator Matthew Weiner finally delivered the punch line to the joke, in the form of the just-deceased Bert warbling “The Best Things in Life Are Free” to a startled Don at the end of Mad Men’s mid-season finale. As he opened his mouth to sing, a chorus of miniskirted secretaries cavorting around him, Morse parted his lips in a smile, and there at last was the gap-toothed grin of Finch, the quintessential American striver.

How to Succeed opened on Broadway in 1961, the year after the one in which the debut episode of Mad Men is set. It ran more than 1.400 performances, collected seven Tonys and a Pulitzer Prize, and spawned a 1967 feature film (in which Morse reprised his stage role) as well as several revivals, most recently in 2011. I never saw Morse do the show on Broadway, but I did see a traveling production featuring former child star Darryl Hickman, who channeled the same boyish charm Morse conveyed in the movie.

The musical was based on a satirical 1952 book by Shepherd Mead, who worked his way up from the mailroom to a vice-presidency at ad agency Benton & Bowles. Mead’s book was a parody of the self-help manuals that were a staple of the era (my father, a supermarket executive, kept a copy of a book titled How to Win Success Before 40 by his bed for years, probably until he was at least 39. It’s available on Amazonto this day).

The musical was based on a satirical 1952 book by Shepherd Mead, who worked his way up from the mailroom to a vice-presidency at ad agency Benton & Bowles. Mead’s book was a parody of the self-help manuals that were a staple of the era (my father, a supermarket executive, kept a copy of a book titled How to Win Success Before 40 by his bed for years, probably until he was at least 39. It’s available on Amazonto this day).

But when How to Succeed was adapted into a musical, it became a comic version of Mead’s own career. As Act 1 begins, J. Pierrepont Finch is a lowly New York City window washer, a literal outsider peering at the career he covets through the windows of Manhattan skyscrapers. One day he enters the offices of a company called World Wide Widget and, applying the precepts of the book How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, ascends to chairmanship of the board within the unlikely span of two weeks (despite a major strategic blunder along the way: becoming Vice President of Advertising).

Like Don, Finch is an imposter bluffing his way to success, “a man way out there in the blue riding on a smile and a shoeshine,” as Willy Loman is remembered at his funeral in Death of a Salesman. Mad Men is How to Succeed through a glass, darkly; both chronicle boardroom backstabbing, office romances and corporate folly in mid-century Manhattan. Strip Mad Men of context and consequences, angst and alcoholism; throw in a few Frank Loesser songs, and you have How to Succeed.

And that’s what Don Draper saw when Bert Cooper sang to him (and by the way, let us here acknowledge Jon Hamm’s evolution as an actor over the course of the series; in this seventh year he has exposed new depths of Draper’s inner terror and despair): a distorted reflection of himself, perhaps his destiny, the once magnetic wunderkind reduced to an eccentric loner in his dotage.

And because reflections are always backwards, Bert Cooper’s message to Don was also delivered in reverse. It was actually a warning from beyond the grave: The best things in life always come at a cost.

March 7, 2014

Hokey smoke, June Foray!

I got to speak with a legend today — the great voice actress June Foray, the original voice of Rocky the Flying Squirrel, Natasha Fatale, Nell Fenwick and a zillion other cartoon characters. Wikipedia says she’s 96; . Whatever her age, she was charming but also no shrinking violet: “I’m still working and I still get awards; I don’t even have room for them all,” she told me firmly.

I got to speak with a legend today — the great voice actress June Foray, the original voice of Rocky the Flying Squirrel, Natasha Fatale, Nell Fenwick and a zillion other cartoon characters. Wikipedia says she’s 96; . Whatever her age, she was charming but also no shrinking violet: “I’m still working and I still get awards; I don’t even have room for them all,” she told me firmly.

I got to speak with her through the good graces of comics/animation/TV Renaissance man Mark Evanier, who was good enough to speak to me about the new Rocky and Bullwinkle comic he’s writing for IDW Publishing (the artist is Roger Langridge). We had so much Moose and Squirrel to discuss that I didn’t have a chance to tell Evanier how very fondly I remember DNAgents and his Blackhawk run, or that I had attended his panel on the great Carl Barks at San Diego Comic-Con back in 2001.

It’s great to be able to talk to people you’ve long admired, and even get paid for doing it.

March 4, 2014

Let it bleed: Thoughts on Pynchon’s “Bleeding Edge”

Gravity’s Rainbow bent my brain. I was in Buffalo, living in a dilapidated third-floor walkup with a roommate, a few sticks of discarded furniture and a sizable number of cockroaches. The apartment had once been spacious and gracious, with bow windows overlooking a tidy Italian neighborhood. But now it was long since worn and whittled down, its fireplace sealed off, its original floor plan hidden by a drop ceiling so flimsy that merely shutting a door made its panels flop in their frames.

Gravity’s Rainbow bent my brain. I was in Buffalo, living in a dilapidated third-floor walkup with a roommate, a few sticks of discarded furniture and a sizable number of cockroaches. The apartment had once been spacious and gracious, with bow windows overlooking a tidy Italian neighborhood. But now it was long since worn and whittled down, its fireplace sealed off, its original floor plan hidden by a drop ceiling so flimsy that merely shutting a door made its panels flop in their frames.

I was jobless, just out of college, where I’d been keen for Kurt Vonnegut, as many of us were back then (though I’d been an even bigger fan of folk singer Richard Fariña’s only novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, which I carried around with me until the little paperback frayed and fragmented). That’s why I wound up with two brand-new hardcovers of Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions from different donors for my birthday.

I took one back to the bookstore, hoping to get cash for it, but was told I could only exchange it for other books. My eye fell on Gravity’s Rainbow, fresh out in softcover. I was just 21 and knew very little, but I understood GR was important, a literary event. I also happened to know one of the few personal details anyone knew about Thomas Pynchon, which was that at some point he’d hung out with Richard Fariña.

I hefted the book and looked at the back, which bore the words A screaming comes across the sky. Even after selecting it along with The Food Stamp Gourmet (a hippie cookbook I continued consulting even after my circumstances improved), I still had exchange value coming, so I threw in Pynchon’s first novel, V.

After getting the disappointing Breakfast of Champions out of the way, I turned to V.; I’d already read a chapter of it, “In Which Esther Gets a Nose Job,” in an anthology. Quickly I comprehended what had inspired Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, its caustic tone and18th-century-style chapter headings.

But Fariña’s book was Dr. Seuss compared to V. The novel was entertaining, but also frustrating. I kept expecting its labyrinthine plot to resolve itself, yet it never did. Puzzled but intrigued, I moved on to GR. And fell into a vortex.

Ostensibly the novel was set in Europe at the end of World War II, but it seemed more like an intricate hallucination about the war. I roamed the stateless territory of the Zone, a medley of mad songs buzzing in my head. I glutted myself on nauseating jelly-filled candies and bananas prepared a thousand different ways. Deep inside a toilet in the Roseland Ballroom I discovered a vast underground world. I parsed extravagant interpretations of the phrase “You never did the Kenosha Kid” and met a sentient lightbulb named Byron.

In a word, I became immersed. With no bosses or parents or teachers to distract me, I’d carry the book to a little park nearby and sit under a tree, underlining passages and scribbling in the margins as I struggled to grasp elements of chemistry, history, psychology, ballistics and a dozen other disciplines key to the story. Literally as well as literarily, the book was rocket science.

As I tried to wrap my head around it all, I surrendered to Pynchon’s intricate thought process. Of course, anyone who reads a novel enters its writer’s mental landscape, assimilates at least some of his or her assumptions and judgments and worldview; otherwise they’d simply close the book. But with his Byzantine imagination and polymathic erudition, Pynchon demands more commitment than most.

Yet while he may be the most important American novelist of our time, Pynchon is still in the business of selling books (tellingly, in June 2012 he finally consented to the release of all his works in e-book format). Like any contemporary author, he faces the paradox of crafting literature in a post-literate age, of writing long-form narrative when the very names of many media — Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram — denote how minuscule our attention spans have become.

How does a writer stay relevant in the age of the Internet? One strategy: Write about the Internet.

So with Bleeding Edge Pynchon turns away from the historical (albeit highly imagined) settings of GR, Mason & Dixon and Against the Day and toward the recent past: He sets the novel in 2000-01 New York City. (This is symmetrical with V., much of which is also set in New York, in the 1950s, only a few years before the book was published in 1963.)

Yet despite its modern-day setting, Bleeding Edge is structured like a 1930s detective novel by Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler (Pynchon’s 2009 Inherent Vice is also a detective story; aficionados know it shares its fictional universe with Bleeding Edge, evinced in the latter when a character sings the imaginary oldie “Soul Gidget,” described in Vice as “one of the few known attempts at black surf music”). Like Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon or Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep, fraud examiner Maxine Tarnow begins an investigation and soon finds that every door she enters, each shady character she meets, tangles her deeper in a web (or Web) of conspiracy. At its nexus is a ruthless Silicon Alley entrepreneur named Gabriel Ice.

Two motifs overarch Pynchon’s oeuvre: entropy and paranoia. In Bleeding Edge the former manifests in the deflation of the late ’90s tech bubble, epitomized in a fin de siecle dot-com revel that evokes some of the most eloquent writing in the book and harks back to the early Pynchon story “Entropy,” set around a lease-breaking party.

The paranoia motif coalesces, with unsettling plausibility, around the attacks of Sept. 11. To a reader like me who was in New York City that ghastly morning, 9/11 is like a doomsday clock whose ticking grows louder in proportion to the depths of intrigue down which Maxine spirals.

Even so, Bleeding Edge is very funny. Like Nick Charles in Hammett’s The Thin Man, who has a high-society wife but consorts with grifters and gunsels, Maxine straddles two worlds: she is a more or less respectable Manhattan mom, but also a MILF who carries a gun in her purse as she roams a demimonde teeming with digital-age Damon Runyon characters. She has lost her license but finds, like Hammett’s Sam Spade, that being a bit disreputable may be good for business. Her voice blends Borscht Belt one-liners with witty wordplay.

Plucky Maxine may be Pynchon’s most likable protagonist ever, but she’s as shallow as her creator’s allusions are deep, and many members of the novel’s typically profuse supporting cast are so insubstantial that the main thing that distinguishes them are their whimsical names (Felix Boïngueaux, Conkling Speedwell, Carmine Nozzoli, Chazz Larday, to cite just a few). Pynchon is not immune to sentiment; he has compassion for his characters, but he engages with them from the remote distance of the inveterate satirist.

And Bleeding Edge is filled with satirical conceits that are quintessentially Pynchonian. There’s the American Borderline Personality Association, whose members dance to Madonna’s “Borderline” as they cruise to destinations like the Mason-Dixon Line; a “private nose” who uses his super sense of smell in forensic investigations, and a Queens strip club called Joie de Beavre, whose manager is named Stu Gotz.

But fanciful (and often downright silly) though it is, Bleeding Edge is dense with details about its real-world time and place: turn-of-the-millennium music, movies, TV shows, videogames, fads, fashions, furniture and more, much more. The book is meticulously — in fact, obsessively — researched. Scrawled notes about everything from Mayan mythology to the CIA’s Montauk Project litter the margins of my copy, making them as messy as the ones in that paperback of Gravity’s Rainbow that fell into my hands long ago.

More than Vineland or Against the Day, Bleeding Edge reintroduced me to the Thomas Pynchon who bent my brain with GR; like an addict returning to his drug of choice after years of abstinence, I could feel long-dark neural passageways flaring back to sudden life. But unlike GR, Bleeding Edge isn’t about events that took place before I was born; it’s Pynchon’s take on times I’ve lived through myself.

I witnessed some of the genesis of the commercial Internet, first at the failed online service Prodigy before the Web was even woven, and later at several early websites. In the days during which Bleeding Edge takes place, I was on the fringes of Silicon Alley and the tech bubble, covering them in a trade publication I edited. I partied with engineers and overnight zillionaires; I interviewed for a job with a magazine swollen with dot-com ads, now long gone. On 9/11 I was still at my trade magazine in the Chelsea district, not far north of what became known as Ground Zero.

In the days of irrational exuberance before the millennium ended and the Towers came down, I still harbored some ideals about the Internet; I fancied it a force for democracy, a powerful tool that would put secrets once accessible only to initiates at the fingertips of the common man. But now that it has been my daily workplace for some years, it seems to me that it has empowered people chiefly in the sense that corporations are people, and that most of what it has put at people’s fingertips is a limitless repository of tripe and hype.

Pynchon’s view of the Internet is even longer and more jaundiced than mine; the pattern he perceives arcs like a rainbow all the way back to the era in which most of his first novel is set: the 1950s. It seems appropriate that Maxine’s creator chooses the character of her father, Ernie, an Upper West Side leftie, to deliver judgment:

“You know where it all comes from, this online paradise of yours? It started back during the Cold War, when the think tanks were full of geniuses plotting nuclear scenarios,” Ernie lectures Maxine. “…Your Internet was their invention, this magical convenience that creeps now like a smell through the smallest details of our lives, the shopping, the housework, the homework, the taxes, absorbing our energy, eating up our precious time. And there’s no innocence. Anywhere. Never was. It was conceived in sin, the worst possible. As it kept growing, it never stopped carrying in its heart a bitter-cold death wish for the planet, and don’t think anything has changed, kid.”

Smart though it is, some have referred to Bleeding Edge as “Pynchon Lite” (The New York Times’ Michiko Kakutani coined the term in her review of Inherent Vice) compared to the epic length and Gordian complexity of Gravity’s Rainbow. I think it’s the work of a great novelist who makes no apology for the intellectual rigor of his work, but also sees no disgrace in doing a novelist’s job: to share his view of the world with the world, as much of it as he can possibly reach. He’s not ashamed to entertain.

A friend recently pointed out that in Woody Allen’s Blue Jasmine, it strains credulity that a prospective Congressional candidate would not realize very quickly that the woman he is dating is not what she pretends to be. That Allen, now 78, found it necessary to contrive a chance street encounter to advance that plot point may betray his unfamiliarity with such newfangled advances as search engines and social networks.

Pynchon is only a year and a half younger than Allen, but as its title implies, Bleeding Edge shows him fully conversant with current culture, technology and events. Whether that fluency is organic or attained via research matters little; what matters is that his observation is as sharp and relevant as ever.

But age may have annealed Pynchon’s blazing talent with a touch of humility, made him willing to meet readers halfway (or at least a quarter or fifth of the way). If it has, I think we are better off for it.

September 2, 2013

Bleeding Cool interview

I was honored to be interviewed by Dan Wickline of Bleeding Cool, the venerable comics blog whose roots go all the way back to the Usenet in 1993 (coincidentally, the year in which Fandemonium is set). Wickline was obviously highly familiar with the novel and asked some incisive questions; hopefully my responses were halfway intelligent.

I was honored to be interviewed by Dan Wickline of Bleeding Cool, the venerable comics blog whose roots go all the way back to the Usenet in 1993 (coincidentally, the year in which Fandemonium is set). Wickline was obviously highly familiar with the novel and asked some incisive questions; hopefully my responses were halfway intelligent.

One of the things I said: “In Fandemonium the superheroic transformation — the gamma bomb explosion, the radioactive spider bite, the shedding of mundane outer clothing in a convenient storeroom or phone booth to reveal the spectacular champion hidden underneath — is a metaphor for growing up. All the characters need to transcend unevolved versions of themselves and transform into the superheroes of their own lives.”

Read the full text of the interview here.

August 28, 2013

The roots of Fandemonium

The lovely folks at Books etc., a fine online bookseller in the United Kingdom, invited me to file a guest post on their blog about Fandemonium. Here’s what I came up with:

“Write what you know” is the writer’s proverbial first rule. So my

decades-long passion for comic books was a logical jumping-off point for my

first novel, Fandemonium, which revolves around a comics and fantasy

convention.

I’ve attended quite a few cons, and the creators and fans I encountered at

them inform Fandemonium’s cast of characters – particularly dissipated comic

book writer Ray Sirico. But Fandemonium is about more than just comics, and

many other aspects of my life went into it.

For example, as a media professional I’ve seen corporate takeovers and

downsizings of the sort that propel the novel’s plot. As an entertainment

journalist I’ve interviewed actors, which helped shape the character of

bellicose actress Harmony Storm. Like Fandemonium’s striving artist and

publisher Tad Carlyle, I’ve struggled to succeed in New York City after

emigrating from the hinterlands (Carlyle’s from South Dakota; I’m from

Buffalo, New York). And along with many other comics fans, I was once an

awkward adolescent like the book’s youngest protagonist, Fred D’Auria, for

whom fantasy offers refuge from often harsh reality.

All these elements come together, comically and sometimes dramatically, at

the nexus between art and commerce, fantasy and reality, hype and hope: a

comic-con.

Welcome to Fandemonium!

- See more at: http://www.booksetc.co.uk/blog/#sthas...

August 9, 2013

The protagonist interviews his creator, part 2

rom “A Rake’s Progress” by William Hogarth, circa 1732-33.

Fictional comic book writer Ray Sirico’s interview with his own creator, FANDEMONIUM author Rick Schindler, resumed after a lengthy pause for liquid refreshment.

Ray S.: That’s better. So, we’ve established that I am an ideal subject for a novel. But why set it in 1993?

Rick S.: Well, 1992 was the death of Superman—

Ray S.: Who?

Rick S.: Superman. Strange visitor from another planet with awesome powers and questionable fashion sense. The prototypical superhero.

Ray S.: Not where I come from. There’s nothing about him in FANDEMONIUM. I oughtta know, I live in there.

Rick S.: Oh, right. That’s because I thought a novel about comics might be more fun if I populated its background with imaginary comics characters instead of the ones everybody already knows.

Ray S.: And I commend your decision. But why 1993?

Rick S.: Well, Superman—

Ray S.: Fuck Superman, whoever he is. The reason 1993 is important is because that’s the year the World Wide Web was born.

Rick S.: You’ve never heard of Superman, yet you know about the Internet?

Ray S.: You established in the novel that I do; it comes up several times. And 1993 was the year CERN published the first graphical website.

Rick S.: What’s that got to do with a novel about comic books?

Ray S.: Note the term graphical.

Rick S.: You’re suggesting the Web is like an enormous comic book?

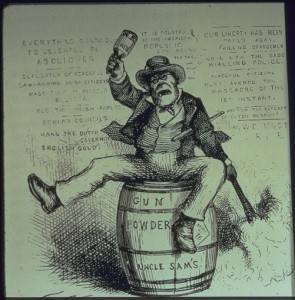

Thomas Nast cartoon from Harper’s Weekly, 1872.

Ray S.: More like an enormous rack filled with them. Consider the Web’s profusion of gaudy images, its lurid banners and blurbs, its dearth of nuance, its abundance of funny animals and crappy ads for dubious products, its reduction of narrative to a binary battle between good guys and bad guys. Hell, look at Twitter, where communication is limited to bursts of 140 characters— pretty much the same number you can fit into a comic book caption or word balloon.

Rick S.: You know about Twitter?!

Ray S.: I have my own feed.

Rick S.: You’re not even real, for Christ’s sake.

Ray S.: You don’t need to be real to tweet; you hardly even need to be literate. How old were you when you learned to read?

Rick S.: What? Uh, 4, maybe.

Ray S.: In school?

Rick S.: No. My mom says I taught myself to read from comic books.

Ray S.: As did I. As did any number of others of our generation. Comics are the natural cradle of literacy.

Rick S.: Oh please. The medium is barely a century old. Even if you count newspaper comics and editorial cartoons—

Ray S.: What about Winsor McCay? What about Thomas Nast? What about Beardsley? What about Hogarth?

Rick S.: Well, I suppose those are sorts of graphical storytelling—

Ray S.: As are Japanese woodcuts, stained glass church windows, medieval tapestries, illuminated manuscripts, Egyptian hieroglyphics, prehistoric cave paintings—

Rick S.: You’re drunk.

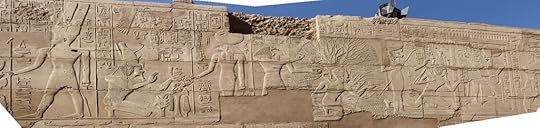

Ray S.: Granted, but that doesn’t mean I don’t know what I’m talking about. The Book of Kells! The Elgin Marbles! The Temple of Karnak! The Cave of Altamira!

Frieze from the Karnak temple in Egypt.

Rick S.: You’ve lost your Elgin marbles. You’re ranting.

Ray S.: Of course I am. It’s what I do. The point is, comics, cartoons, graphical storytelling, call it what you will, transcend literacy and language. They were there before literacy existed, and they’ll be there after it’s dead and buried in the vast necropolis of the Internet. In the future there will be no words: only images and emoticons, binary clicks and grunts ricocheting endlessly across the cyberverse. Here’s to postliteracy!

Rick S.: Dick and Jane, we hardly knew ye.

July 17, 2013

The protagonist interviews his creator

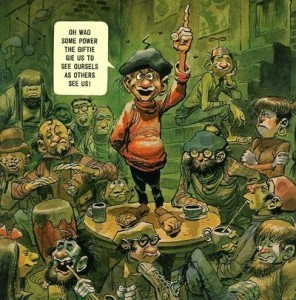

A beatnik recites Robert Burns on the cover of Yak Yak No. 1 (aka Dell Four Color No. 1186), May 1961. Art by Jack Davis.

(Note: It was originally intended for the author to interview Ray Sirico, protagonist of his novel Fandemonium. However, Mr. Sirico consented to speak only on the condition that he ask the questions.)

Ray S.: Before we begin, let me commend you on having the perspicacity to write a book about me, however maladroitly.

Rick S.: Uh, thanks. I think.

Ray S.: What prompted you to choose me as a subject? Was it my charisma, my sex appeal, my groundbreaking work? Or some combination of the above?

Rick S.: Well, something in your story spoke to me—

Ray S.: Of course. You saw me as a role model.

Rick S.: Not exactly—

Ray S.: No need to be embarrassed. It’s entirely natural that to a second-tier talent like yours, mine would blaze like a beacon, illuminating a lofty goal at which to aim, even though it could never be achieved. No offense.

Rick S.: None taken, inasmuch I was thinking of you more as a cautionary tale.

Ray S.: You deceive yourself. I am your aspirational alter ego, your superheroic identity. Why else would we have the same initials?

Rick S.: Holy crap. I never thought of that.

Ray S.: Of the six letters in my surname, all but one appear in your own, in similar order. What do you suppose that’s about?

Rick S.: You’re suggesting that deep beneath my placid exterior, there’s a big fat drunken Italian comic book writer struggling to get out?

Ray S.: I’m already out. And finding the exit wasn’t much of a challenge. I own funny animal comics more complex than you.

Rick S.: O wad some pow’r the giftie gie us, to see ourselves as other see us.

Ray S.: That is the worst attempt at a Scottish accent it has ever been my misfortune to hear. If you’re going to quote Burns, you need to drink some Scotch first.

At this point Mr. Sirico paused to take liquid refreshment. The remainder of the interview, which resumed after a lengthy hiatus, will follow in a subsequent post.

June 21, 2013

FANDEMONIUM’s fantasy characters

FANDEMONIUM character Galaxia-Five’s name stands for something, but you won’t find out what in the book.

FANDEMONIUM is the story of some people who come to a comics convention one weekend in 1993. But along with those people come a bunch of other characters – the fantasy figures all those conventioneers are involved with one way or another.

Those fantasy characters have their own stories, but I couldn’t cram them into the novel without getting in the way of the human beings I wanted to write about. So I put them someplace there’s always plenty of room: the Internet.

In the Fantasy Characters Guide on rickschindlerbooks.com you can learn why volatile actress Harmony Storm’s TV character is called Galaxia-Five; the secret identity of the maniacal Master Chef referenced in Chapter 9; the reason Skylord’s nemesis Baron Brain is so bitter, and hundreds of other details that I couldn’t manage to keep contained in my fevered mind (some illustrated here by FANDEMONIUM reader C.J. Solomon). You can even find out where restaurant-chain mascot Prince Pepperoni lives, or what the weather is like on the planet Dolora (not very nice).

Or you could start reading FANDEMONIUM at the beginning and proceed until you come out the other end. That works too.

What is Baron Brain so upset about anyway?

Doomerang, whom one FANDEMONIUM character calls “a sociopath in a bondage mask.”

The maniacal Master Chef from Chapter 9.

June 2, 2013

Gobsmacked

The Septic’s Companion, a British slang dictionary, defines “gobsmacked” as “surprised, taken aback.”

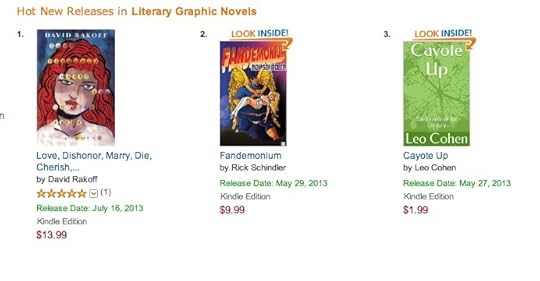

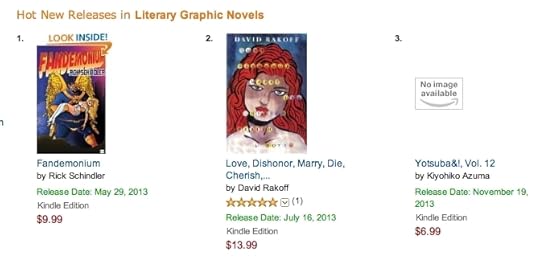

Since Wattle Publishing, publisher of my novel FANDEMONIUM, is English, “gobsmacked” seems a particularly apt word to describe my reaction to this news: The book, which was published on Friday, has already reached No. 2 in Amazon’s Hot New Releases in Literary Graphic Novels.

My gob was also smacked pretty hard at receiving my first-ever customer review, on Amazon U.K. Full disclosure: I do not know Anna, who headlined her review “Fandemonium is LOL!” and wrote: “This book didn’t disappoint & it’s the funniest book I’ve read in a long time. It was cleverly written and I finished in record time.” But I would say that she is quite obviously a discriminating (and fast) reader.

I am delighted as well as soundly smacked in the gob (which, the Septic’s Companion informs me, means “mouth”) at the rousing welcome my crazy novel has received in the marketplace, and I offer my thanks to the readers who have welcomed it. And having said that, I will shut my gob.

Update June 5: I must reopen my gob long enough to add that FANDEMONIUM subsequently climbed to No. 1 in Hot New Releases — and it’s been there ever since!

May 21, 2013

The season of comics

The main action of FANDEMONIUM takes place at a comics convention over the weekend of June 18-20, 1993. So I find it fitting that the novel will be published almost exactly 20 years later than it is set, the span of a generation, on Friday, May 31.

The book had to be set in summer. For me, summer was always the season of comic books, of leisurely afternoons catching up with Batman and Spider-Man, of debating who would win in a fight, Superman or the Hulk (answer: Hulk). Summer was when the giant-size comic book annuals came out, when you could give them the attention they deserved without the annoying distraction of math homework. And of course, summer is the season of the biggest real-life comic book convention, San Diego Comic-Con.

Summer is when days are longest, when there is the most time to daydream. And comics are daydreams.

Walt Disney’s Summer Fun, 1959. Cover painting possibly by Don McLaughlin.

Films are like dreams; they are viewed in the dark, where they immerse you. But comics are a daylight medium, suited to languorous afternoons outdoors when there is time to pause between pages, study the clouds, and imagine what it would be like to soar among them like Superman or Skylord, the fictional superhero at the center of FANDEMONIUM.

The Italian word for comics is fumetti — literally, “little puffs of smoke,” referring to dialogue balloons. And what are clouds but the puffy thought balloons of young lives, the canvases on which we paint our waking dreams, the screens upon which we project our fondest fantasies? And when better to do that than on an endless summer day, when life’s possibilities are as boundless as the cloud-dappled sky?

Rick Schindler's Blog