Jake Eagle's Blog, page 2

March 25, 2021

Living in a state of presence

Can you imagine being completely present as you move through your most mundane, ordinary daily chores? Among the many tools we offer for conscious living, is the mindful practice of sensory awareness.

For me, this is a most useful practice for actually living in extended moments of presence—even a whole day—by paying impeccable attention from one moment to the next and using my senses to do it.

Below is a memorable experience of this degree of presence from my time as a Zen student many years ago, while practicing the simple act of sweeping.

Sweeping the FloorI close my hands around the broomstick and feel a cool sensation and the pull of gravity as I lift the broom in the air. I survey my task at hand—the porch wrapping around the meditation hall.

I place the broom bristles on the deck floor and hear them brush along the surface in what, before, was an unconscious motion.

Now I notice that one hand pushes the handle in one way while the other pulls in the opposite direction. That’s what makes sweeping happen.

I notice the gathering of dust and sand brought on deck by the many shoed feet, before sandals are discarded at the door of the meditation hall.

I notice the breeze wants to push back the particles where I’ve swept and I decide to start at the other end of the deck, so as to sweep with, rather than against, the wind.

I feel my weight shifting from foot to foot as I head to the other end of the porch while noticing knot holes, that look like eyes in the floorboards, as I pass over them.

I hear the river behind the hall, creating a rhythm as it tosses and turns on its path downhill. I tune my broom to the rivers’ heartbeat and dance with sweeping moves across the floor.

An Awesome SurpriseI notice a Zen-mate standing in my way with her back to me. Honoring our vow of silence, I gently touch the back of her foot with my broom, rather than say excuse me. She turns around and makes eye contact, for the first time all week.

She is the person who sits next to me in zazen, yet I have never seen her face. Her kind eyes are a brilliant cat’s-eye-green and her smile a surprise—because emotions and expressions have been restricted and all eyes have been focused downward.

Such a momentary connection after a week of going within makes the act of connecting more poignant, like the first taste of fruit after a long fast.

I’m aware that all moments of connection with others, even a momentary glance, could always feel this precious and this profound if both people are present.

I continue sweeping, noticing the brushing sound on the deck floor, feeling the breeze, hearing the river toss and turn.

The idea is that in anything you’re doing—washing dishes, showering, brushing your teeth, driving to work—you can have this level of presence by paying attention to your senses from one ordinary moment to the next.

The post Living in a state of presence appeared first on Live Conscious.

February 27, 2021

Seeing Through Existential Anxiety

Have you ever noticed that even when things are going well, somewhere in the recesses of your mind, you may feel antsy or a little bit anxious? And other times, it may be much more pronounced. There’s a good chance that what you’re experiencing is existential anxiety—the angst that comes from being human, regardless of what’s going on. It’s always with us, but during times of strife, like a pandemic, it increases because the pandemic heightens our awareness of our mortality and the fragility of life. Also, the pandemic exaggerates another reality, which is that the future is uncertain. Both of these—mortality and uncertainty—are aspects of life for which most people don’t have a good solution. As far as I can tell, there are two ways to deal with existential anxiety.

Have you ever noticed that even when things are going well, somewhere in the recesses of your mind, you may feel antsy or a little bit anxious? And other times, it may be much more pronounced. There’s a good chance that what you’re experiencing is existential anxiety—the angst that comes from being human, regardless of what’s going on. It’s always with us, but during times of strife, like a pandemic, it increases because the pandemic heightens our awareness of our mortality and the fragility of life. Also, the pandemic exaggerates another reality, which is that the future is uncertain. Both of these—mortality and uncertainty—are aspects of life for which most people don’t have a good solution. As far as I can tell, there are two ways to deal with existential anxiety.

Before exploring how to deal with existential anxiety, I want to share my thoughts about why this is worth doing—for ourselves individually, our relationships, and society at large. If we don’t find ways to reduce existential anxiety, we inhibit our health, limit intimacy, and create a more polarized society.

Inhibit our physical and mental health. Existential anxiety leads us to seek ways to distract and soothe ourselves, some of which are not healthy—such as eating comfort foods, drinking alcohol, using drugs, and social media. All of these unconscious strategies can inhibit long-term health and well-being.

Limit intimacy. Existential anxiety arises, in part, because we fear death—ours and the people we love. And to reduce the pain of losing those we love, one of our unconscious strategies is to limit how much we allow ourselves to open our hearts and connect as deeply as possible.

Create a more polarized society (which we clearly see happening now). When human beings feel anxious and uncertain, we tend to turn toward other people, looking for a shared way to make sense of what’s going on. We look for like-minded people. This is why during times of uncertainty, we see conspiracy theories abound. And people who hold a different view represent a threat to what we are trying to hold onto, so we reject them and create polarization.

Two solutionsNow, let’s explore two ways to manage or reduce our existential anxiety— doing so will enhance our health, open the door to greater intimacy, and help us see through the illusion that making other people the enemy will solve our anxiety.

To reduce our anxiety about death and uncertainty (largely unconscious), we seek to feel we are part of something that will extend beyond our death—to create a lasting footprint. So we create things toward that end: children, businesses, products, art, community, religion, and stories that bestow a sense of continuity. My children will carry on . . . people will read the book I wrote after I die . . . family or communal stories that include me will be told for generations to come.

For example, in the corner of my office, I have an antique globe sitting in a wooden stand. When I was thirteen-years-old, it was given to me by a friend of my grandfather, who was probably seventy-five at the time. I interviewed this man for a school project, and he saw something in me that made him believe I would cherish and care for the globe in his office, which I had admired. To this day, I look at that globe every night before I go to bed. I comfort myself as I remember the older man who gave it to me, long since gone, and I contemplate the idea that someday I will find a young person to whom I will pass along this globe. That young person will appreciate the globe and share a story with a future generation about the man who gave it to him or her.

Another example of creating a lasting footprint— I once worked with a successful businessman who started his first business in his twenties. When he was in his eighties, he was starting his fifth business. His life was so full and productive that it was as if he didn’t have time to contemplate dying, and he overcame any concerns about the uncertain nature of life by continually creating things he could control. Did he experience existential anxiety? I don’t know. His strategy appeared to be rather successful.

But I think that he was more the exception than the rule. As I get older and observe people around me aging, what I see is an increase in existential anxiety without many good ways to deal with it. So, I’ll offer an alternative approach that is based on changing your level of consciousness.

Shifting levels of consciousnessExistential anxiety arises when we are in a state of safety consciousness, where we live most of the time—trying to protect and control and continually evaluate our performance. And the strategy I just described—attempting to create a lasting footprint—also comes from safety consciousness.

Another approach is to change our level of consciousness. For example, when we access spacious consciousness—a state of mind in which time, words, measurements, and comparisons don’t exist—existential anxiety isn’t relevant. There are various ways to access spacious consciousness, but the most direct path I know of is the A.W.E. method we developed, which was proven highly effective in the clinical study we conducted at UC Berkeley. This method quickly leads to an emotional experience of awe.

This works because you access awe in relationship to whatever it is that you fear losing—your life, another person, control. When you access awe, you connect with something greater than your anxiety. In part, this approach is a matter of switching your focus from one side of a coin (for example, fear of losing someone you love) to the other side of the same coin (the depth of your love). It seems counterintuitive because you might think that if you feel your love more strongly, you will also feel more anxiety about losing the source of that love. But that’s not what happens if you go fully into awe.

As we access awe, our concerns about time and loss are replaced with present moment sensations that disrupt our anxious thoughts. The loss we fear is enveloped by our love and appreciation for that which we fear losing.

For example—think of a person you fear losing. Take a minute to get in touch with how much they mean to you. Give your full and undivided attention to how precious this person is to you. Be with those feelings and thoughts. Let them fill you. Then wait for the length of time it takes for one inhalation, staying with the feelings and thoughts. When you exhale, allow your exhalation to be a little longer than normal. Notice how you feel.

When you find your way to the other side of your anxiety, you connect with your love and appreciation for being alive. The key is to move through the anxiety—not deny it—and when you do this, your relationship to your anxiety will shift.

C.S. Lewis captured this experience when he said, “The pain then is part of the happiness now. That’s the deal.” If we are to love—life, a pet, a person, an accomplishment—we will experience loss. Worrying about that loss—consciously or unconsciously creates anxiety. The anxiety inhibits our health and our relationships. Using this A.W.E. practice to experience awe turns down the volume of existential anxiety by helping us inhabit our love of life.

The post Seeing Through Existential Anxiety appeared first on Live Conscious.

January 21, 2021

The Power of Awe

Maybe you don’t need to sit on your meditation cushion longer or more often. Maybe you don’t need to learn how to self soothe. Maybe you don’t need to work on unresolved issues from childhood. Or, maybe you do. I don’t know, but I do know that if you start developing your awe muscle, either you won’t need to do those other things, or if you do, they’ll be easier.

Maybe you don’t need to sit on your meditation cushion longer or more often. Maybe you don’t need to learn how to self soothe. Maybe you don’t need to work on unresolved issues from childhood. Or, maybe you do. I don’t know, but I do know that if you start developing your awe muscle, either you won’t need to do those other things, or if you do, they’ll be easier.

Awe is an emotion that hasn’t gotten a lot of attention in the past—an overlooked gem. And when people consider awe, they often think of it as something they can experience as a reward for having done “their work,” or the result of some significant insight, or what happens after enough hours on a meditation cushion. But based on our research, awe does not have to be a reward that is at the end of your journey; it can be a starting point.

If you follow our work, you may have heard that we conducted two large-scale awe studies in cooperation with UC Berkeley and NorthBay Hospital last year. The results—not yet published—are impressive: decreases in depression, anxiety, loneliness, pain, and increases in wellbeing and mindfulness. But what’s even more impressive is how the participants got these results.

In less than a minute or two a dayFor twenty-one days, the participants practiced accessing awe three to five times a day, and the practice only takes about ten to twenty seconds each time. Think about that for a moment.

In about the time it takes to read the short paragraph above, people were accessing awe.

So, a few questions. What is awe? Why is this simple practice getting such great results? And, how can you learn to do it?

Awe is an emotion that carries us beyond our typical experience of the world to the point of amazement. Most studies of awe use extraordinary sources of stimulation to induce awe, for example, sitting on the rim of the Grand Canyon, standing at the foot of a redwood tree, listening to a remarkable piece of music like Beethoven’s Für Elise, or some kind of virtual reality simulation. All of those work, but they aren’t necessary. This was part of our unique discovery.

You can discover awe in the ordinary. And we’ve developed a simple technique to help you do so. If you want to experience this more fully, you can apply for our course, The Power of Awe, which occurs via Zoom, in four 1-hour sessions, February 4th, 11th, 18th, and 25th. I believe there are only four spaces available as of the publication of this article.

Time ExpandsThere are many reasons why the awe practice produces meaningful results. The primary reason is the way awe alters our sense of time. As time expands, our sense of urgency disappears, we become more patient, which changes the way we relate to other people. The other significant thing that happens is a brief resetting of our nervous systems.

I think of my awe practice as a way to wake myself up several times each day. I come off autopilot and give my attention to something that amazes me. It’s like a respite, a break, a positive infusion that keeps my nervous system from getting stuck in defense physiology.

Does awe solve all my problems? No, but by developing my awe muscle, I find everything else a little bit easier. Awe shifts my state of consciousness, almost instantaneously. Most of the time, we live in a state of safety consciousness—focused on being productive and getting things done, but if we access awe, we experience less stress even when we’re in safety consciousness. And if we are in safety consciousness and want to be in heart consciousness but are having a hard time making the shift, accessing awe can open that pathway.

Awe is almost always available to us; we don’t need to wait. We can insert moments of awe throughout our day. Wake up in the morning, don’t have time to meditate, take a moment to access awe. Getting ready to have a difficult conversation with your partner and you feel anxious about it, take a few moments and access awe. Feeling tired, but there is some task you need to do, step into a moment of awe. Going to bed at night, hoping to have a good night’s sleep, before you turn down the sheets, take a moment to access awe. The more you do it, the easier it becomes.

The post The Power of Awe appeared first on Live Conscious.

January 1, 2021

Where You Place Your Attention Determines the Quality of Your Life

Welcome to 2021—may it be a year to celebrate!

Welcome to 2021—may it be a year to celebrate!We’re going to offer you a simple suggestion to help make 2021 a year to celebrate. If you know who we are, you can skip this paragraph and go right to the good stuff. For the thousands of you who joined our mailing list in the past few months and haven’t heard a word from us—we’re sorry we neglected you. We are Hannah and Jake Eagle, the co-founders of Live Conscious, and our purpose is to help people live more consciously.

Okay, here’s our suggestion for the year ahead. Choose where you place your attention—choose who and what you attend to every day.

Where we place our attention determines the quality of our lives.Have you heard of the “attention economy?” In short, the attention economy aims “…to keep us in a profitable state of anxiety, envy, and distraction.”* Profitable for social media companies and businesses who hijack our attention and distract us from attending to the most meaningful things in our lives.

We believe that unwittingly participating in the attention economy is antithetical to living consciously, so we have opted out. Last year we stopped writing articles because we were tired of trying to come up with catchy headlines and optimal search terms that would drive traffic to our website. That’s why you didn’t hear much from us in 2020. Rather than writing articles last year, we dedicated our attention to two things.

We focused our attention on reducing suffering related to COVID. We did this by teaming up with UC Berkeley, NorthBay Hospital, and Dr. Michael Amster to conduct a large scale awe study. We proved that our original and simple awe practice—which only requires a couple of minutes a day—decreases anxiety, depression, pain, loneliness and increases wellbeing, joy, and mindfulness. It was a gratifying experience and a great place for us to direct our attention.We focused attention on the people who have participated in our courses—our retreats and online courses—by holding weekly Zoom sessions and engaging in ongoing personal email correspondence. In the process of attending to so many people we love, we filled our hearts.Not only did we choose two large projects on which to focus our attention, but hour by hour, we shifted our attention away from watching too much news to reading great books and listening to inspiring music. We dropped off social media and attended to our garden. We gave extra attention to notice the beauty surrounding us—even during a pandemic—and find the humor in being human.

The Year AheadIn the year ahead, we will be conducting more research on awe, and we’ll give you more attention—sharing ideas, tools, and practices. We will not spend any time or attention trying to create catchy headlines, so if you want to learn more about our work, look for our emails with the following headline: SECURITY LOVE AWE.

We use these three words because they represent what we have to share with you. The model we pioneered, Three Levels of Consciousness, offers practical ways to experience security, love, and awe. And although we won’t be conducting any in-person retreats during the pandemic, we will be offering online courses. Each course we offer is twenty-one days long. Most of them are limited to sixteen participants, incorporating our unique “buddy system,” whereby everyone pairs up with another course participant.

So, as you move into the New Year, consider where you place your attention? What and who do you attend to? Instead of allowing others to hijack your attention, pulling you from one shallow thing to the next, what will your life be like if you learn to direct your attention to more profound human experiences and more meaningful connections? If that idea captivates your attention, keep an eye out for our emails with the headline SECURITY LOVE AWE. We also invite you to explore our next online course, The Power of Awe, which you can find by clicking this link.

In January, we’ll be redesigning our website homepage to make it easier for you to learn more about the three online courses we offer: How We Make Meaning, Thrilled To Be Alive, and The Power of Awe.

We wish you a Happy New Year.

With love and laughter,

Hannah and Jake Eagle

* How To Do Nothing, Resisting the Attention Economy, by Jenny Odell

The post Where You Place Your Attention Determines the Quality of Your Life appeared first on Live Conscious.

Where You Place Your Attention Determine the Quality of Your Life

Welcome to 2021—may it be a year to celebrate!

Welcome to 2021—may it be a year to celebrate!We’re going to offer you a simple suggestion to help make 2021 a year to celebrate. If you know who we are, you can skip this paragraph and go right to the good stuff. For the thousands of you who joined our mailing list in the past few months and haven’t heard a word from us—we’re sorry we neglected you. We are Hannah and Jake Eagle, the co-founders of Live Conscious, and our purpose is to help people live more consciously.

Okay, here’s our suggestion for the year ahead. Choose where you place your attention—choose who and what you attend to every day.

Where we place our attention determines the quality of our lives.

Have you heard of the “attention economy?” In short, the attention economy aims “…to keep us in a profitable state of anxiety, envy, and distraction.”* Profitable for social media companies and businesses who hijack our attention and distract us from attending to the most meaningful things in our lives.

We believe that unwittingly participating in the attention economy is antithetical to living consciously, so we have opted out. Last year we stopped writing articles because we were tired of trying to come up with catchy headlines and optimal search terms that would drive traffic to our website. That’s why you didn’t hear much from us in 2020. Rather than writing articles last year, we dedicated our attention to two things.

We focused our attention on reducing suffering related to COVID. We did this by teaming up with UC Berkeley, NorthBay Hospital, and Dr. Michael Amster to conduct a large scale awe study. We proved that our original and simple awe practice—which only requires a couple of minutes a day—decreases anxiety, depression, pain, loneliness and increases wellbeing, joy, and mindfulness. It was a gratifying experience and a great place for us to direct our attention.

We focused attention on the people who have participated in our courses—our retreats and online courses—by holding weekly Zoom sessions and engaging in ongoing personal email correspondence. In the process of attending to so many people we love, we filled our hearts.

Not only did we choose two large projects on which to focus our attention, but hour by hour, we shifted our attention away from watching too much news to reading great books and listening to inspiring music. We dropped off social media and attended to our garden. We gave extra attention to notice the beauty surrounding us—even during a pandemic—and find the humor in being human.

The Year Ahead

In the year ahead, we will be conducting more research on awe, and we’ll give you more attention—sharing ideas, tools, and practices. We will not spend any time or attention trying to create catchy headlines, so if you want to learn more about our work, look for our emails with the following headline: SECURITY LOVE AWE.

We use these three words because they represent what we have to share with you. The model we pioneered, Three Levels of Consciousness, offers practical ways to experience security, love, and awe. And although we won’t be conducting any in-person retreats during the pandemic, we will be offering online courses. Each course we offer is twenty-one days long. Most of them are limited to sixteen participants, incorporating our unique “buddy system,” whereby everyone pairs up with another course participant.

So, as you move into the New Year, consider where you place your attention? What and who do you attend to? Instead of allowing others to hijack your attention, pulling you from one shallow thing to the next, what will your life be like if you learn to direct your attention to more profound human experiences and more meaningful connections? If that idea captivates your attention, keep an eye out for our emails with the headline SECURITY LOVE AWE. We also invite you to explore our next online course, The Power of Awe, which you can find by clicking this link.

In January, we’ll be redesigning our website homepage to make it easier for you to learn more about the three online courses we offer: How We Make Meaning, Thrilled To Be Alive, and The Power of Awe.

We wish you a Happy New Year.

With love and laughter,

Hannah and Jake Eagle

* How To Do Nothing, Resisting the Attention Economy, by Jenny Odell

The post Where You Place Your Attention Determine the Quality of Your Life appeared first on Live Conscious.

August 22, 2020

John Weir: Forgotten Pioneer in the Human Potential Movement

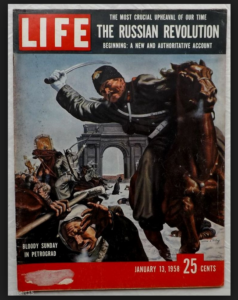

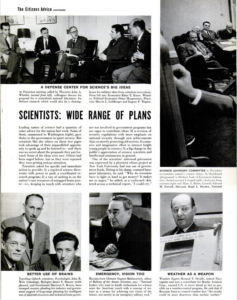

Throughout the past fifty years, the name of psychologist John Weir remains rather obscure compared to Maslow, Rogers and others. However, if you were to look at the January 13, 1958 issue of Life Magazine, in an article titled, Citizens Give Ideas In Crisis, you’ll find a photograph of John Weir alongside men who were already, or were soon to become famous, including: Physicist John A Wheeler, a young Dr. Henry A Kissinger, and Paul Nitze, former director of the State Department’s policy planning.

Throughout the past fifty years, the name of psychologist John Weir remains rather obscure compared to Maslow, Rogers and others. However, if you were to look at the January 13, 1958 issue of Life Magazine, in an article titled, Citizens Give Ideas In Crisis, you’ll find a photograph of John Weir alongside men who were already, or were soon to become famous, including: Physicist John A Wheeler, a young Dr. Henry A Kissinger, and Paul Nitze, former director of the State Department’s policy planning.

The gathering of these great minds was in response to the Soviet Union launching Sputnik in 1957. Although Sputnik only carried a radio transmitter sending out harmless signals, Americans realized the Soviets could have used their new capability to deliver a nuclear missile to the United States. The magazine article opens with a quote from New Deal Senator, Stuart Symington: ‘The American people are ahead of their government in realizing that, if they are to remain free, radical changes must be made in both our thinking and our efforts.” John Weir believed in this need for change. Throughout his professional career as a professor of Psychology at Caltech, a faculty member at NTL Institute, a clinician, and a leader in the human potential movement, he brought about radical changes. Maybe too radical. Perhaps that explains why his name has remained obscure all these years?

I was three-years-old when that article was published. Forty years later, I’d become a psychotherapist and had six years of private practice under my belt. I was feeling confident and self-assured when my practice philosophy was turned upside down as a result of meeting an elderly couple in the parking lot of Whole Foods in Santa Fe, New Mexico Had I known that the man, John Weir, was once featured in Life Magazine, and had been one of the pioneers in the human potential movement, I’m sure I would have been nervous to meet him. Little did I know that on that day my wife, Hannah, and I would decide to continue the evolution of the Weir’s work, and that it would become the focus of our professional and personal lives.

I was three-years-old when that article was published. Forty years later, I’d become a psychotherapist and had six years of private practice under my belt. I was feeling confident and self-assured when my practice philosophy was turned upside down as a result of meeting an elderly couple in the parking lot of Whole Foods in Santa Fe, New Mexico Had I known that the man, John Weir, was once featured in Life Magazine, and had been one of the pioneers in the human potential movement, I’m sure I would have been nervous to meet him. Little did I know that on that day my wife, Hannah, and I would decide to continue the evolution of the Weir’s work, and that it would become the focus of our professional and personal lives.

I watched the couple step down from their road-weary Winnebago. John first, looking like a gnome, then Joyce, looking delicate but feisty. At the time, they were both eighty-five-years old and still traveling around the country teaching their unique brand of personal development workshops. I knew little about them, except that a trusted client of mine, a very bright and highly successful man had said to me, “You have to meet John and Joyce Weir.” I’d been working with this client for a couple of years and I trusted and appreciated his judgment. He had an international reputation for the work he was doing in the world, and as he was entering the elder stage in his life, my client believed that we needed to find ways to preserve the legacy of elders who had made a unique contribution in their lifetimes. I was to find out later that the Weirs’contribution to psychology was described by a California radio talk show host as “equal to the contribution of Freud.”

David Elkins, professor emeritus of psychology at Pepperdine University and board member of the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, wrote in 2009, “Maslow, Rogers, May, and so many others in that ‘first generation’ are now gone. Deterministic, mechanistic, and pathologizing models once again dominate clinical psychology–despite the fact that psychotherapy research clearly supports humanistic values and perspectives.”

John Weir, a friend of Carl Rogers, was part of that ‘first generation’ of pioneering psychologists. Although the contributions John and Joyce Weir made to the field of psychology haven’t been fully recognized, in 2006, the Weirs’ work was acknowledged in The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. Philip Mix, wrote, “No human development theorist-practitioner from the 1960s to the present has created as radical and powerful an instrument of personal authenticity, accountability, and self-empowerment as the Weirs’ percept language. Moreover, underscoring the Weirs’ unique role in validating the foundational principles of humanistic psychology, no theorist-practitioner has placed personal responsibility for one’s own development so firmly at the core of their personal growth work as did the Weirs.”The primary contribution the Weirs made, which Mix refers to as “percept language,” was a new way for people to communicate, but it was also more than that; it was a new way to construct reality. Their linguistic model has gone through several evolutions since the early 1960s. Over the years it has been called, “transference language,” “ownership language,” “responsibility language,” and, for many years, it was known as “percept language.”

John Weir, a friend of Carl Rogers, was part of that ‘first generation’ of pioneering psychologists. Although the contributions John and Joyce Weir made to the field of psychology haven’t been fully recognized, in 2006, the Weirs’ work was acknowledged in The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. Philip Mix, wrote, “No human development theorist-practitioner from the 1960s to the present has created as radical and powerful an instrument of personal authenticity, accountability, and self-empowerment as the Weirs’ percept language. Moreover, underscoring the Weirs’ unique role in validating the foundational principles of humanistic psychology, no theorist-practitioner has placed personal responsibility for one’s own development so firmly at the core of their personal growth work as did the Weirs.”The primary contribution the Weirs made, which Mix refers to as “percept language,” was a new way for people to communicate, but it was also more than that; it was a new way to construct reality. Their linguistic model has gone through several evolutions since the early 1960s. Over the years it has been called, “transference language,” “ownership language,” “responsibility language,” and, for many years, it was known as “percept language.”

Will Schutz, another pioneer of the human potential movement, and faculty member at Esalen Institute, provides some historical perspective on the Weirs. “In 1947, several students of psychologist Kurt Lewin organized the first laboratory training centered on T-Groups, the ‘T’ standing for ‘training.’ . . . This innovation led to a special advanced workshop at Bethel [Maine], in 1963, designed to focus on personal growth and creative expression. The staff of that workshop included Robert Tannenbaum, Charles Seashore, Herbert Shepard, and myself.

The following year, 1964, Californians John and Joyce Weir, led the first Personal Growth Laboratory at Bethel. They had a profound effect on NTL by introducing nonverbal techniques in the laboratory design.”

It was Carl Rogers who hailed these early encounter groups as, “the most rapidly spreading social invention of the century, and probably the most potent.” Rogers went on to explain, “I believe it is a hunger for something the person does not find in his work environment, in his church, certainly not in his school or college, and sadly enough, not even in modern family life. It is a hunger for relationships which are close and real; in which feelings and emotions can be spontaneously expressed without first being carefully censored or bottled up; where deep experiences–disappointments and joy–can be shared; where new ways of behaving can be risked and tried out.”

Although the Weirs’ work was born in the 1960’s, a time when encounter groups encouraged catharsis, John Weir thought that was insufficient. He explained some of his ideas about group work in one of his very few written documents. “We also insist that self-discipline is a necessary aspect of spontaneity and freedom of expression. Contrary to what has sometimes been said, the kind of personal growth training being described here is not an orgy, or a training program for the expression of hostile impulses, or an excuse for licentiousness. We discourage hostile physical contact. We forbid participants to injure themselves or others.”

It is important to note that John always gave credit to his wife, Joyce. In using the word we, he is acknowledging that Joyce was an important and essential partner in the workshops they designed and conducted. Working as a team, they combined Joyce’s background in expressive dance, Yoga, dance therapy, group psychotherapy, and fine arts, with John’s background as a psychologist and experiential educator.

It is important to note that John always gave credit to his wife, Joyce. In using the word we, he is acknowledging that Joyce was an important and essential partner in the workshops they designed and conducted. Working as a team, they combined Joyce’s background in expressive dance, Yoga, dance therapy, group psychotherapy, and fine arts, with John’s background as a psychologist and experiential educator.

He went on to explain, “The aim of sensory exploration, physical contact, and expressive movement is to reacquaint the participant with his body and its processes. The conscious management of these processes demands a high degree of control and a type of self-discipline that approaches a form of asceticism. One will no longer permit the abuse, neglect, or denial of his newly understood, respected, and prized self. Participants frequently assess this acquisition of self-control as one of the most valuable achievements of their lab experience. It gives added reality and a sense of permanence to their experience of autonomy, ownership, personal responsibility, and self-management.”

John Weir believed that the results from group work occurred faster and were more significant than the results occurring in individual counseling. While teaching psychology at Caltech, he saw some private clients, but within a few years after he and Joyce began running their “personal growth laboratory,” he stopped seeing clients privately and focused exclusively on enhancing the design and delivery of group retreats.

Fast forward to 1998 when my wife, Hannah, and I met the Weirs; by then the Weirs had touched the lives of over eight thousand people. Although they were in their mid-eighties, they were vibrant, present, passionate, and we intoxicated ourselves spending time with them. They both had the rare quality of intently listening without interrupting, and expressing themselves in ways unlike any other people we’d ever met. We experienced exactly what Carl Rogers spoke about, “ . . . relationships which are close and real; in which feelings and emotions can be spontaneously expressed without first being carefully censored or bottled up; where deep experiences–disappointments and joy–can be shared; where new ways of behaving can be risked and tried out.”

Within hours of meeting these two strangers, a deep bond formed. We talked about life, work, sex, pets, and careers. After Hannah expressed her interest in early retirement and gardening, Joyce said, “There’s nothing wrong with that, but how are you going to grow? And how will you grow as a couple?” That question changed the trajectory of our lives.

A few weeks later we immersed ourselves in the last “personal growth laboratory” they ever taught. In Calistoga, California, at a small hot springs motel—with the Weirs’ help—we discovered a new vision of how to live, have fun, grow older, and make a contribution to the world. The days were long and full of experiential activities—activities designed to help us shift our understanding of “reality” indelibly—so that we never saw the world in the same way again. Surface illusions we had about other participants faded away as we came to realize that we weren’t seeing these other people, we were seeing our projections of them.

As a therapist I was aware of the theories of projection and transference, but never before had I been invited to acknowledge and own every one of my projections. I was also aware of the value of being present, but never before had I been shown how to use language as a tool toward this end. The Weirs showed me how to do both of these by changing my language. As I changed the way I spoke with other participants—and especially with Hannah—all conflict disappeared, people’s defenses melted away, and when we collectively stopped distracting ourselves with our projections, we all began to reveal ourselves more honestly and maturely. In one week I experienced more healing, more internal acceptance, and a deeper connection with Hannah than I had as a result of years of therapy.

This transformation was one of John Weir’s goals. He had been concerned that the field of psychotherapy was going in the wrong direction—with too much emphasis on pathology and not enough on healing. He believed the answer required changing the way we use language. Some of that was accomplished by focusing on a person’s health and resources more than focusing on their problems and pathology. In recent years, this has become more common, and some in our profession talk about having a “solution focus” or “outcome orientation,” and not concentrating solely on “the problems.”

But John Weir was aiming at something much deeper than what therapists talk about with clients; what’s more influential is how we use words to talk about the issues they bring to us. John explained to me that in most cultures people speak as if there is one reality out there, and that reality acts upon us. When people speak about the world or their lives in this way, they unknowingly put themselves in the role of the victim. This triggers certain neural responses that produce a defense physiology. A defense physiology will orient people to try and create safety, rather than promote personal growth. Therefore, we need to alter the way we use words so we don’t stimulate a defense physiology in our clients, or in ourselves.

John Weir shaped his powerful ideas, in part, from his study of physics, incorporating and translating them into simple and useful ways to alter our speech patterns. He was specifically interested in the work of John Wheeler, an American physicist, also featured in the Life Magazine article, born two years before Weir, who famously said, “There is no out there out there.” When Wheeler tried to explain this comment, he said it is necessary to distinguish what he called “it from bit”. He said that what we perceive as reality—out there—is just information: bits. We then take that information and create a reality, which we refer to as “it.”

One of the subtlest aspects of John Weir’s work is that he discouraged the use of the impersonal pronoun “it” and, when appropriate, replaced “it” with the personal pronouns “I” or “myself.” For example, “It scares me,” becomes “I scare myself.” And “I can’t bear it,” becomes “I can’t bear myself.” This elegantly simple shift reflected John Weir’s understanding of what John Wheeler was pointing out—a universal truth—there is no single version of reality. We take information that has no inherent meaning and we imbue that information with meaning that is entirely subjective. Then, we act as if the meaning we make is objective and factual. Often, this leads us to argue about who’s right and wrong—at times, even going to war over “it.”

John Weir’s linguistic model made clear that we are talking only about our perceptions of reality, not reality itself. When I use this new way of speaking, I take complete responsibility for myself, stay in the present, stop blaming or praising other people, and stop telling them about themselves. During one of the summer programs at the NTL Institute, John Weir interrupted Carl Rogers when Rogers was teaching a group how to give constructive feedback. John said, “I think it’s better not to lead us to believe we’re giving feedback about someone else, because what I’m really doing—even when I think I’m giving feedback about you—is talking about myself, my perceptions.”

We saw John and Joyce model this idea when we attended their personal growth laboratory in Calistoga, California. Not once, for the entire week, did anyone tell us anything about us. That alone was a remarkable experience. And as we adopted this new way of speaking, Hannah and I forever changed the way we relate to one another. By adopting a few simple guidelines—and continuously practicing— we changed our lives. For example, by eliminating the use of praise and blame we stopped putting our nervous systems in each other’s hands. We took back the locus of control for our emotional wellbeing. By talking mostly in the present tense—talking about what’s happening right now—we stopped rehashing the past, trying to make one another wrong. All of our petty arguments about who said what or who did what ceased. And we began to see each other as individuals, appreciating our differences, instead of being threatened by them.

I also changed the way I work with clients and that resulted in a change in my clientele over time. As I modeled a different way of speaking for my clients—no longer unintentionally validating them as victims—and taught them how to speak in a new way, they stopped victimizing themselves and self-justifying their inappropriate behaviors. The reason this was so effective was that they were hearing themselves in a new way. Changing their language created a new perceptual position, which was followed by a new degree of self-awareness and insights.

For six years after we participated in the personal growth laboratory at Calistoga, Hannah and I privately studied with the Weirs and eventually became stewards of their work. Like Joyce, Hannah decided she wanted to be involved in how we would bring this work to the world. And like Joyce, she became instrumental, partnering with me to demonstrate the transformational power of this paradigm. Both women also brought a feminine perspective to the work, as well as ways to balance the body and mind. After seeing Hannah and I work together for the first time, Joyce Weir said to us, “You’re like us. Jake represents the mind, which was John’s role, and Hannah represents the body, which was my role. And they have to work together.”

Part of the immediacy and depth of my connection with John had to do with my training as a therapist. I was taught to focus more on the structure and less on the content. I pay more attention to how a client communicates rather than what they are saying. Focusing on structure includes noticing things such as whether a client moves toward what they want or away from what they don’t want; whether they associate or dissociate with their emotions; and where the locus of control is in their lives. When the locus of control is external, people tend to victimize themselves. When it is internal, people tend to empower themselves. The brilliance of the language structure that John Weir created is that when clients speak in this way, they immediately shift the locus of control to being internal. They empower themselves.

And although this way of speaking was unique at the time the Weirs introduced it, there was a precedent. The language that the Buddha spoke during his lifetime, Pali, was a “verbing” language. It allowed one to stay in process, not fixing oneself or clinging to a static or permanent state, but rather being in motion, continuously unfolding—which is a foundational premise of Buddhism. For example, Buddhism’s goal of practice, Nirvana, would not be a noun but a verb—Nivana-ing ourselves—(actively) putting out our fires of greed, hatred, and delusion, rather than reaching a state of nirvana. Instead of the Buddha finding a path of enlightenment (a static state), he would be saying that he found a path for enlightening ourselves—an active, continuous process.

Significant numbers of followers of Buddhism were waking up in the time of the Buddha because the language-ing was so radically different. The ideas and words were based upon “verbing” oneself, which helped people recognize that “self” was a process, dependent upon conditions arising and passing away.

John Weir expressed to me his interest and appreciation for Buddhism, but I cannot say to what degree he based his linguistic model on the Pali language. There are similarities, but several differences as well. The Weirs’ work consisted of more than a new way of speaking; and understanding this way of speaking will provide individuals with the essence of their work, as well as tools that can be implemented in working with clients.

To gain a better understanding of how to apply the Weirs’ model, the therapist can begin by modeling and then teaching the following guidelines to clients:

1) Return to Now

As much as possible, talk about what’s happening right now. This applies to one’s internal dialogue as well as the conversations you have with other people.

Many people in the human potential movement, as well as spiritual teachers, advocate the value of being in the present moment. The value of doing so is propelling the popularity of mindfulness practices. While there are many mindfulness techniques being taught, mostly related to meditation, the Weirs developed a way for people to bring themselves into the present every time they speak.

When we apply the guideline ‘Return to Now,’ we redirect the conversation by asking questions such as, “What do you want to do right now? What do you need from your partner now? What do you want to express about what’s happening right now, at this very moment?”

There is very little value in arguing about what one or the other said previously. This is especially true in partnerships. If we believe the other person is honest, why do we challenge them when they tell us how they remember a prior event or prior conversation? If we don’t believe the other person is fundamentally honest, why are we in partnership with them?

It can be very effective to apply this rule when a couple is arguing about who was right or wrong in a situation that happened in the past. When a couple is arguing, the therapist might say, “I perceive what you’re doing as a waste of time. If you’re here because you want to be closer, spending your time disparaging each other isn’t going to help. So, instead of arguing about what happened, I want to encourage you to talk about the present because this is when change occurs, right here and now. I’d like you to talk about what you want right now, at this moment.”

Bringing people into the present moment is a remarkably effective way to alter behavior and communication dynamics. It may not always be the appropriate intervention, there are times when the past needs attention, but when you want to help people be present, invite them to talk about what’s happening now. One of the key phrases I use to accomplish this is, “Ask for what you want instead of complaining about what you didn’t get.”

2) Re-source Your Feelings

John Weir pointed out the obvious, which is that our feelings come from within us. We are the source of all of our feelings, yet, often we ascribe our feelings to other people, and many therapists inadvertently support this misconception.

For example, in a therapy session, a client may relay to the therapist something along the lines of, “My partner makes me feel totally inadequate.” Typical responses from a therapist might be:

“I can imagine that it’s difficult for you to feel inadequate.”

“I remember you telling me that your father made you feel this way in the past.”

“Do you want to connect with your partner when he makes you feel inadequate?”

The concern John Weir would have with the above responses is that they validate the idea that one person makes the other feel the way she feels.

John Weir’s response would be, “Your partner isn’t responsible for how you feel. You are. If you feel inadequate then say, ‘I make myself feel inadequate.’ He would have said something similar to a client who blames someone else for making them feel bad. For example, he would coach such a client to say, ‘I make myself feel bad.’”

Typically, the best way I’ve found to convey this idea to my clients is to model it for them. For example, I might say, “I’m frustrating myself with this conversation. I want you to notice that I’m not saying you’re frustrating me; I’m doing this to myself.”

In many cases, John Weir advocated turning nouns and adjectives into verbs as a way to help people re-source their feelings, such as:

“I am delighted” becomes “I delight myself.”

“I am scared“ becomes “I scare myself.”

“You frustrate me” becomes “I frustrate myself.”

“You make me angry” becomes “I anger myself.

Of course, some grammarians may find this challenging. If so, John Weir would say, “You challenge yourself.”

The purpose of this change in linguistic structure is shifting the locus of control from external to internal, and removing the static and permanent quality that is implied when we say things like, “I am disappointed.” This is very different than saying, “I disappoint myself,” which implies activity, motion, and doing. If I am doing something to myself, such as making myself feel a certain way, then it is possible to stop doing what I’m doing or do something different.

Understanding this shift, that we are responsible for how we feel, is more easily adopted when clients also adopt the third guideline.

3) Remove Praise and Blame

By removing praise and blame we eliminate any judgment that may go along with taking responsibility for how we make ourselves feel. A client will not help herself by saying, “I am rejecting myself with my partner,” (instead of saying, “My partner is rejecting me.”) if she then blames or judges herself for doing this. Therefore, to accept that we create our own emotional states we help ourselves greatly to remove all praise and blame, which are two sides of the same coin.

In addition to using praise and blame to judge others or ourselves, we often use them as ways to control other people. We use praise and blame excessively with children and frequently with other adults. When a person is praised, they feel as if the person doing the praising is making them feel good. When a person is blamed, they feel as if the person doing the blaming is making them feel bad. The praiser and blamer become responsible for how the other person feels.

John and Joyce Weir eliminated the use of both praise and blame. They replaced them with the following linguistic structures:

Instead of blame, use the expression, “I disappoint myself when __________.”

Instead of praise, use the expression, “I appreciate __________.”

With this simple change in speech patterns, the speaker is making it clear that he or she is talking about their own experience.

So, for example, when my 13-year-old grandson tells me he’ll clean up his mess in the dining room before dinner, and then he doesn’t, I can either blame him for not doing what he said he would do, or I can let him know that I disappoint myself when he doesn’t do what I thought he agreed to do. When I blame him he is likely to get defensive and feel bad about himself. When I express that I am disappointing myself, I am giving him information about me. When I speak to my grandson in this way, he doesn’t fear being judged by me. John Weir believed that no other person ever judges us because they are never telling us about us; they are telling us about themselves—about their way of making sense of whatever is going on for them.

Some people are concerned that if we don’t blame other people for their unacceptable behaviors, they won’t change those behaviors. But there is another way to think about this. If I care about another person, when that person tells me that they are making themselves feel bad in response to my behaviors, I am highly motivated to change my behaviors, and I do so as an act of free will, not coercion or manipulation.

The fourth guideline is based in large part upon projection theory. The idea is that unacceptable aspects of our personality are likely to be projected onto other people. To eliminate this tendency, it is necessary to clearly differentiate whether I am speaking about another person or my projection of that other person.

4) Recognize the difference between “you” and “you-in-me.”

John Weir suggested that we make clear when we are talking about another person versus when we are talking about our projection of that other person. We do this linguistically, by using “you” or “you-in-me.” The latter is what I use when I want to express that I am talking about my projection of a person, not the actual person.

This is not something most people will use as part of their normal day-to-day conversations, but as a therapeutic intervention, it is extremely illuminating. It can also be taught to couples who are in therapy as a tool they can use during times of conflict or misunderstanding.

The point is to be explicit as to when I am talking about the other person, and when I am talking about my perception/projection of that person.

For example, if someone walks into the room and I think he looks sad, I might say, “When you walked into the room, I thought that you-in-me looked kind of sad.” I use the pronoun “you” when I reference him walking into the room because that is an observable event, not open to interpretation. But whether he is sad or not is open to interpretation, so in this case, I use the expression “you-in-me.” Actually, I’m not talking about him at all, I’m telling him about me and my perception of him.

Again, this may sound a bit awkward when someone is initially exposed to it. But, during times of stress or conflict, or as a therapeutic intervention, helping our clients slow down and be very explicit as to whether they are talking about the other person or talking about their perception of the other person is remarkably clarifying and eliminates a great deal of confusion.

John Weir was perhaps ahead of his time, but the application of his ideas is timeless. So, why were his ideas not widely accepted, say for example, in comparison to Rogers and Maslow? I speculate that the lack of wider adoption of John Weir’s ideas is because they involve asking people to take full responsibility for themselves, to own all aspects of themselves.

It is easy to understand why the therapies developed at the same time John Weir was developing his theory were widely accepted in that the responsibility was on the therapist to understand and appreciate their client’s perspective. What client wouldn’t value this? Whereas John Weir’s model encourages the therapist to remind the client that what the client is sharing is just a perspective, not the truth, not reality, but a perspective—or what John Weir liked to call a “percept.” He was not saying the things people talked about —a memory or trauma, an argument or falling in love—were made up; it’s the meaning of these things that’s made up. For some clients, and in certain situations, this may not be helpful. But for those clients and therapists who were ready to step into this high level of personal responsibility, as well as freedom, the Weirs’ model was and continues to be as “radical and powerful an instrument of personal authenticity, accountability, and self-empowerment,” as I’ve ever used.

It is easy to understand why the therapies developed at the same time John Weir was developing his theory were widely accepted in that the responsibility was on the therapist to understand and appreciate their client’s perspective. What client wouldn’t value this? Whereas John Weir’s model encourages the therapist to remind the client that what the client is sharing is just a perspective, not the truth, not reality, but a perspective—or what John Weir liked to call a “percept.” He was not saying the things people talked about —a memory or trauma, an argument or falling in love—were made up; it’s the meaning of these things that’s made up. For some clients, and in certain situations, this may not be helpful. But for those clients and therapists who were ready to step into this high level of personal responsibility, as well as freedom, the Weirs’ model was and continues to be as “radical and powerful an instrument of personal authenticity, accountability, and self-empowerment,” as I’ve ever used.

Today, Hannah’s interest in retiring so that she could garden has been replaced with a new vision. The two of us now work together teaching personal growth labs very similar to what the Weirs did for forty years. Working with the same intent, which is to foster personal responsibility and celebration of everyone’s uniqueness, has become the passion and focus of our lives. Like the Weirs, Hannah and I have taught many people to create more freedom in their lives by taking responsibility for themselves. And like the Weirs, we are blessed with a desire to offer this radical and powerful gift to as many people as we can in our lifetimes, and we are grateful to John and Joyce Weir for their generosity and trust in us.

John Weir was included in Life Magazine, along with some of the most brilliant minds of the time because he had a brilliant mind and he used it to transform the lives of anyone lucky enough to have discovered the work he and Joyce created.

Humanistic Psychology: A clinical Manifesto. A Critique of Clinical Psychology and the Need for Progressive Alternatives. David Elkins, 2009, page 85

A Monumental Legacy, The Unique and Unheralded Contributions of John and Joyce Weir to the Human Development Field. Philip J. Mix, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 42, no. 3, September 2006 276-299

Elements of Encounter, William Schutz, 1973, page 3

The Monumental Legacy: The unique and Unheralded Contributions of John and Joyce Weir to the Human Development Field, Philip J. Mix, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 42 No 3, September 2006, page 279

(pp. 182) Rober Ewen (1988) (Personality: A Topical Approach – Theories, Research, Major Controversies and Emerging Finds)

The Laboratory Method of Changing and Learning: Theory and Application. K. Benne, L.P. Bardod, J.R. Gibb, R.D. Lippit, 1975

(pp. 10-11) Carl Rogers (1970) (Encounter Groups)

A Monumental Legacy, “The Unique and Unheralded Contributions of John and Joyce Weir to the Human Development Field”. Philip J. Mix, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 42, no. 3, September 2006 276-299

The post John Weir: Forgotten Pioneer in the Human Potential Movement appeared first on Live Conscious.

July 29, 2020

Part 2: Trying To Be Present Creates Anxiety—Creating Presence Reduces Anxiety

So, you want to learn to be present—to live in the moment? There are times and places when this may be helpful, but in Part 2 of this article I want to point out that trying to be present may be contributing to your anxiety.

So, you want to learn to be present—to live in the moment? There are times and places when this may be helpful, but in Part 2 of this article I want to point out that trying to be present may be contributing to your anxiety.

Why? Because when we think about being in the moment—and “moment” is defined as an indefinitely short period of time—we are using time as our measuring stick. The problem with this approach is that most people think of time as being limited; we only have so much time. And, therefore, this approach, which is at the center of our civilization, creates urgency and angst.

Too much focus on time

Our focus on time relates directly to our focus on productivity. We want to get things done. For example, when we have meetings to discuss something, we allocate a certain amount of time. Contrast this with some Aboriginal and Native American cultures that, for example, use a “talking stick.” The “talking stick” is passed around the circle until every one has nothing more to say. That’s how they know the meeting is over. Time is not a factor.

But in our culture, time is a factor, just about all the time. And as the pace of our culture speeds up—instant messaging, emailing, and instant gratification with Amazon overnight delivery—we may be losing valuable character traits. Traits such as: patience, discipline, and awareness of the consequences of our actions—not just today, but for years and generations to come. I believe that in our time-oriented culture we are unlikely to solve the problems related to time by focusing on time. Another time management course may not be the answer. And repeated attempts to be in the moment may not be the answer.

Instead, I want to share with you a new approach to experience the benefits of living in the moment, but without any urgency or angst. So, just for a minute (do you see how time creeps in even when I prefer to avoid it?), I invite you to consider an alternative to using time as the lens through which you view your world.

Enter the world of space

When I stop using time as my measuring stick, and instead I become aware of spaciousness, I’m living within what I call, “spacious-consciousness,” and all urgency and angst drop away. As my perspective (consciousness) changes, the world around me appears to change. To quote the poet, David Whyte, “When your eyes are tired, the world is tired also.”

As I see the world through spacious eyes, instead of trying to be present—in the here and now (as measured by time)—I experience presence.

Are you familiar with the expression, “She has such presence.” When we say this we are typically referring to the way a person comports herself—the way she occupies space. We sense the person is fully present, yes, and also embodied, congruent and unflappable.

Being fully present means I’m attending to what’s happening now. Being embodied means it’s not just my mind that’s present, but I’m in my body—connected, feeling, and emotionally available. Being congruent means that I’m communicating a single message, not saying one thing with my words and another with my body language, but rather, conveying the same message with my words, body language, and behaviors. And being unflappable—calm regardless of the circumstances—is largely the result of not focusing on time.

During “difficult times” in my life (again, notice this expression relates to time), I become flappable—reactive—and my sense of spaciousness shrinks. The same thing happens when I experience conflict with another person. In these situations I’m reacting to my perception of time, because when I don’t like how I feel I urgently want to escape my discomfort. I think I can do so by running away or sometimes by asserting myself—winning—and proving I’m right.

Running away doesn’t create presence. Neither does asserting my point of view, although I may mistake assertiveness for presence, but assertiveness is an example of force, which is not the same thing as presence. Presence and force are very different. Force is born out of fear. Presence is born out of existence. Presence is part of my existential nature, the space I occupy prior to making meaning.

Space exists prior to making meaning

Think about this. There is a space that exists—a state of awareness—prior to making meaning. Victor Frankl said, “Between the stimulus and the response there is a space and in that space is our power and freedom.” Frankl was talking about our power and freedom to make choices. I’m talking about accessing that space between the stimulus and the response as a way to create presence in my life.

The more I learn to live in that space, fewer things weigh down my consciousness. In that space I can soar (like an Eagle :-)). For me, spaciousness is a shift in which things in the foreground—turmoil, drama, and crises—move to the background and the background—spaciousness—moves to the foreground. This shift is more profound than any other I’ve experienced.

This idea of shifting from time-consciousness to spacious-consciousness exemplifies the underlying value of the Live Conscious practice, which is realizing and remembering that my experience of the world is dependent on the ways in which I make meaning. I can make meaning by using time as my filter, or I can make meaning by using space as my filter—and the meanings I make, which drive my beliefs and behaviors, will be very different.

If you want to start living with more presence, think ’space.’ And if your first question is, “How long will this take?,” it will take you longer than if you ask, “How can I do this?” Try to stop measuring and evaluating things in time.

To begin, use the three tools I offered in Part 1 of this article. They allow you to start from the familiar perspective of time-consciousness and then open a door through which you take yourself into spacious-consciousness. As a reminder, the tools I shared in Part 1 were:

Return to Now

Tell fewer stories

Learn to be present with discomfort

The next step is to start becoming more aware of spaciousness. Notice when you contract and tense yourself. Notice when you expand and relax yourself. Feel the difference in your body.

And if you don’t have a meditation practice, I encourage you to start meditating ten minutes a day. If you already have a practice, take the first few minutes of your practice to play around with expanding your sense of space. To do this, begin by expanding your awareness beyond your physical body. Allow your awareness of space to extend out into the room in which you are sitting. And, if you are able to do so, allow your awareness of space to extend beyond the room . . .

The post Part 2: Trying To Be Present Creates Anxiety—Creating Presence Reduces Anxiety appeared first on Live Conscious.

June 16, 2020

Part 1: Trying To Be Present Creates Anxiety — Creating Presence Reduces Anxiety

Why are so many of us exploring mindfulness practices, meditation, and yoga? I believe this is because as the velocity of our lives increases, we seek to create balance by creating some spaciousness in our lives. This is certainly true for me—I want more spaciousness.

Why are so many of us exploring mindfulness practices, meditation, and yoga? I believe this is because as the velocity of our lives increases, we seek to create balance by creating some spaciousness in our lives. This is certainly true for me—I want more spaciousness.

In Part 1 of this article I will share with you some steps you can take to be more present, even while living in a fast paced culture. Then, in Part 2, I will share a truly transformative leap you can take that changes the entire game of life. I believe both are necessary—the small steps and then the leap—because when I focus only on being more present, without understanding how to create presence in my life, I inadvertently make myself anxious.

To begin, I want to share my experience. The more tension I have in my life the more I weigh myself down. When I feel weighed down or overwhelmed, one of the most disappointing side effects is that I’m not present, therefore I’m not available to have meaningful and loving connections with people. Without those connections and love in my life, I spiral further into dissatisfaction.

The steps I’ll share with you in Part 1 of this article help me be present and stay more connected with other people—even though life is whirling and rushing all around me. When I want to slow down and connect I can do three things:

1. Return to now

When I’m talking with another person, especially if there is tension or conflict, I can bring the conversation back to now. I do this by asking simple questions of the other person and myself. “What can we do right now in this moment to connect?” “What do I need right now in this moment?” “What do you need from me right now in this moment?”

The power of now is that it represents the greatest opportunity to bring about change. We can’t change the past and we can’t be sure what the future will bring. But we have great opportunity to make this moment the way we want or need it to be.

The challenge for most of us is that we have learned to talk about the past, often as a way to justify what we’re doing in the present. And we have learned to talk about the future, often as a way to threaten (“If you don’t change your behavior I won’t stay with you”), or to cajole, (“It’s no big deal, it won’t happen again, you’ll see, everything will be fine.”)

In Live Conscious, we use the expression, “Return to now,” as a simple reminder to do what Ram Dass wrote about in his famous book, “Remember, Be Here Now.” Most people think the title of that book was “Be Here Now,” but he realized the key is remembering to be here now. And the simplest way we have found to do that is to talk about what’s happening now.

2. Tell fewer stories

The second thing I can do is to stop telling stories. Not all stories and not forever, but when there is interpersonal tension I help myself by telling fewer stories.

Many of my stories are intended to justify my actions or prove the other person was the cause of my current problems. Neither of these helps me reconnect with someone.

Can stories be useful? Sure. For one thing, a story can be a way to reveal more about myself, to make myself vulnerable, to seek to be better understood. But what would happen if I asked myself before telling a story, “What’s my intention behind telling this story?” For one thing, I would be more conscious of what I’m doing. And if I were to ask this question, there are many stories I would not tell.

The other problem with telling stories is that when I do so I often dilute my message—dilute myself. Why not simply state what I want, how I make myself feel, or take responsibility for what I’m projecting onto the other person. All of these bring me back to now.

3. Learn to be present with discomfort

Another reason I avoid being here now is because I may not want to feel negative feelings. So, part of our practice in Live Conscious is creating space to acknowledge how we feel, even when we don’t feel good.

We have developed a three-part model that we refer to as the PRO model. (You can read that article by clicking this link). PRO stands for Pond, River, Ocean. Each one represents an energetic state that we may find ourselves in. The Pond is the state we are in when we are feeling stuck or unresourceful. When in the Pond we often want to get out as a way to escape our discomfort.

I believe that I am often better off if I go into my feelings of discomfort, fully acknowledging them—hopefully in a mature way. The PRO model offers a way to do this. All things are temporary, including my uncomfortable feelings, except when I resist them. When I resist, my discomfort seems to persist.

In summary, Part 1 of this article describes three things I can do to be here now. These steps help me have healthier connections with the people I care about, and this helps me cope better with the velocity and pace of modern life.

In the second part of this article I’ll introduce a fresh perspective, not so much about how to be present, but how to create presence. And, I encourage you to practice what’s in this article in the meantime. The ideas contained above lay the foundation for what’s to come next.

The post Part 1: Trying To Be Present Creates Anxiety — Creating Presence Reduces Anxiety appeared first on Live Conscious.

May 19, 2020

How to Work with Chronic Fatigue, Mild Depression and Erectile Dysfunction

When I wrote the headline for this article I thought it sounded like the opening for a good joke, (A Christian preacher, a Catholic priest, and a Jewish rabbi are out on a boat for the day…), but this isn’t a joke and I don’t have a punch line to share with you. Instead, I want to share a very pragmatic approach for dealing with the challenges that come from chronic fatigue, mild depression, and certain types of erectile dysfunction. This article will present an alternative view for dealing with these challenges.

When I wrote the headline for this article I thought it sounded like the opening for a good joke, (A Christian preacher, a Catholic priest, and a Jewish rabbi are out on a boat for the day…), but this isn’t a joke and I don’t have a punch line to share with you. Instead, I want to share a very pragmatic approach for dealing with the challenges that come from chronic fatigue, mild depression, and certain types of erectile dysfunction. This article will present an alternative view for dealing with these challenges.

All three of these “problems” embody a certain physiological state. To help explain this I’ll share with you the “Physiology Map.” (NLP Master’s Training Manual, 1993).

Rev up

Our autonomic nervous system includes two different branches, the sympathetic and parasympathetic. On this map, the lower half represents the parasympathetic nervous system and the upper half represents the sympathetic nervous system. It is our sympathetic system that revs up in emergencies or stressful situations when we may have to “fight or flee.” Heart rate increases, blood pressure increases, pupils dilate, and there is a surge of adrenaline.

Calm down

And it is our parasympathetic system that allows us to “rest and digest.” During times of low stress, reading a good book, or sitting quietly, this is the system that controls our basic bodily functions.

“… the physiological effects caused by each system are quite predictable. In other words, all of the changes in organ and tissue function induced by the sympathetic system work together to support strenuous physical activity and the changes induced by the parasympathetic system are appropriate for when the body is resting.” (American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, v71, 2007)

When we look at the left side versus the right side of the map we see a continuum that reflects our frame of reference; is it internal or external? We each operate within a continuum, some of us use a more internal frame of reference while others use a more external frame of reference. Those who are more external (left side of the map) tend to measure themselves against the feedback and opinions they receive from other people. Those who are more internal (the right side of the map) rely more on their own judgments, feelings, and opinions, and are less inclined to ask for advice.

By identifying one’s frame of reference (internal or external) and one’s autonomic nervous system activity, we can create a map containing four quadrants, each one consisting of certain character traits, emotions, and attitudes, as described below:

Wind: peaceful, self-contained, unattached and passive

Earth: stable, responsive, carefree and cheerful

Fire: active, angry, excited, blaming and impulsive

Water: anxious, reserved, pessimistic and quiet

What I commonly see when I work with people struggling with chronic fatigue, mild depression, or certain forms of erectile dysfunction, is that all these issues/symptoms relate to a pattern in which people resist going into the Fire quadrant. Studying over 500 patients for the past 25 years my observation is that people struggling with chronic fatigue, mild depression, or certain forms of erectile dysfunction generally resist the Fire quadrant and are stuck in the Water quadrant.

Chronic fatigue

One might expect a person struggling with chronic fatigue to be identified on the lower portion of the map because they seem to lack energy. However, more often than not these people have highly activated sympathetic nervous systems, which manifests as anxiety. This is part of why they feel fatigued, because they expend a great deal of energy being anxious.

Many therapeutic solutions for addressing chronic fatigue direct the client toward self-soothing practices like meditation or affirmations. These approaches are inviting the client to go from the Water quadrant (anxious) to the Wind quadrant (peaceful), which is physiologically very hard to do without passing through the Fire quadrant. Notice the thick black line between these two quadrants that represents a barrier. It is physiologically rare to go directly from a state of anxiety to a state of equanimity, especially when people have a high degree of internal mental chatter.

People must proceed through the Fire quadrant as a way to discharge some of their built-up energy (arrow #1). This requires a willingness to feel some of their emotions, and hopefully express those emotions in appropriate ways. When this is done the client’s physiology will down-regulate from sympathetic arousal to parasympathetic rest, rejuvenation, and recovery.

Therapeutic strategies that encourage clients to unilaterally forgive others or love themselves are attempts to bypass Fire and go directly to Wind. Based on my observations, this strategy seldom works and usually results in very long term treatment.