Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 81

August 3, 2016

Take in the quiet, robotic wastelands of The Signal From Tölva

Big Robot, the studio behind the quirky “tweedpunk” survival game Sir, You Are Being Hunted (2013) has returned with more robots. This time, however, the tone is a little more serious, with the newly announced The Signal From Tölva, which imagines a future when space-faring groups of robots spend their time searching through what’s left of long-dead civilizations. The game takes place on Tölva, where something has been found, and you must follow the signal to find it.

As such, you play as a lonely robot explorer trying to discover what that something is. But that’s not entirely true. As Big Robot explain, you actually play as someone (or something?) that has remotely hijacked a “Surveyor,” the humanoid drone you see through the eyes of on the planet’s surface. But you aren’t tied to the first one you possess, as if and when it meets its demise, you can hack into another and continue the journey. “Remote control, via an interplanetary network,” Big Robot explains. “That has implications for both how the game plays, and what the story says.”

will following the signal lead to anything good?

Although The Signal From Tölva is being billed as an exploration and combat game, the trailer notably spends much more time on discovery. You pick your way around towering and abandoned machinery by flashlight, collecting baubles left in the husks of buildings, and of course, searching for light markers that hopefully lead you towards that elusive something. Meanwhile, the presentation of combat is less upfront than you might expect, showing distant landscapes where battles rage on. Although combat is a vital element, the heart of the game seems to be the reverently quiet travels through decaying marks of a lost civilization.

Though the planet is ostensibly dead, there are other “lifeforms” like yourself—other robots also seeking control. But, are they autonomous or being controlled by someone else, just like you? In any case, fighting these, rather than any native animals, only adds to the anxiety of searching for something unknown on a ruined planet.

Big Robot uses the word “haunted” to describe Tölva, which does beg the question: will following the signal lead to anything good? They say that following this path could lead to enlightenment, but the muted ruins of an empty planet beg to differ. Even if it does, what would that look like for robots who exist post-humanity? The Signal From Tölva hints at something quiet, sinister, and lonely. But also something you can’t help but reach towards.

Learn more about The Signal From Tölva here. It will be out for Windows and Mac in early 2017.

The post Take in the quiet, robotic wastelands of The Signal From Tölva appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Goat, the Devil, and DOOM

The first time Black Phillip, a perfectly normal-looking goat, appears in Robert Eggers’ 2015 horror film The Witch, the viewer is struck with a sense of unease. This isn’t any fault of Phillip’s. If anything, he should be the most reassuring aspect inthe gloomy story of a 17th century family’s exile to the New England wilderness. Within an atmosphere of dread and fear, Phillip all but mugs for the camera in every one of his scenes. He gives his shaggy head a puzzled cock in the middle of a somber barnyard tableau with perfect comedic timing. He rears up to waggle his stumpy front legs in a funny little dance as twin children call his name. Despite everything he does to counter it, though, Black Phillip remains a menacing figure. His horizontal pupils, great curved horns, and matted beard, lingered on by the film’s camera, form a knot of unconscious concern. He’s a goat, and goats can be disturbing.

///

id Software’s 2016 iteration of DOOM is full of monsters. The player, assuming the role of the semi-mythological Doom Marine, works to beat back the forces of hell spilling into a sci-fi Martian research base. Zombie-like creatures shamble through the opening moments—fleshy training wheels whose fumbling movements and crumbling bodies ease the player into the game’s combat systems—but are soon overwhelmed by a more threatening group of demons.

Goat physiology is spread throughout DOOM’s enemy design. Taking its cues from the 1993 original, id blends goatish features directly with human figures (the minotaur-like Baron of Hell and the hulking, massively horned Cyberdemon) or has its characteristic eyes, horns, hooves, and legs incorporated into flying skulls, musclebound “Pinky” demons, and floating, spiky Cacodemons. Though more insectile than mammal now, the fire-throwing Imp, first depicted on the 1993 DOOM’s cover as a smirking, horned beast-man with tongue lolling out between pointed fangs, retains a goat’s springy movements and short, muscular legs.

Each of the game’s demons look as discomforting as expected. Their bodies are warped versions of human and animal—a perversion of nature that recalls the 19th century occult illustrations of Jacques Albin Simon Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal (1818) and Eliphas Lévi’s Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (published in two volumes in 1854 and 1856). The creatures, like the haunting sketches lining the pages of European demonology and black magic books, unsettle the audience by hearkening back to imagery designed to prod at the nerve centers of a Western cultural tradition whose fears revolve, naturally, around its dominant religions.

///

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when the goat became associated with evil, but a likely source is the Torah and Old Testament’s Book of Leviticus. In detailing the ritual behavior provided to the Israelites from God, Leviticus’ text introduces the concept of the scapegoat—a literal goat, metaphorically burdened with a community’s sins, sent away to die in the desert. The practice (thought to be fairly common in ancient Near Eastern societies) stems specifically from verses in Leviticus in which Aaron is instructed to “cast lots over . . . two goats, one lot for the Lord and the other lot for Azazel. And Aaron shall present the goat on which the lot fell for the Lord and use it as a sin offering . . . (Leviticus 16:8-9).”

The importance of “Azazel” in this verse has splintered theological interpretation. Some take the word as a compounded term meaning “complete removal” while others consider it the proper name of a fallen angel (who is again referenced in the apocryphal Book of Enoch as the first teacher of human vanity and weapon-making). In either case, the goat chosen not to be sacrificed, but cast out, is decided by supernatural chance. And, regardless of exact interpretation, the end result is the same: the goat, through no fault of its own, becomes an embodiment of sinfulness.

a literal goat, metaphorically burdened with a community’s sins

///

DOOM 2016’s easiest difficulty level is represented by a small human skull in a military helmet. As the player moves it up to the highest challenge setting, the human skull progressively morphs into a goat’s. The hardest setting—“Ultra-Nightmare”—is a mutation of the previous level’s straightforward goat skull, the nubs of bone near its temple jutting out into larger horns. The implication is that tougher gameplay—increasingly vicious demons, better equipped to rip the player apart in more frequent death scenes—equates to the game’s evil enemies growing in power.

This is a suggestion DOOM makes again and again throughout its levels. As the story requires the Doom Marine to travel from the corridors and laboratories of the moon base to the bowels of hell itself, the difficulty is raised proportionally—a natural coupling of gameplay challenge and narrative progression that echoes the structure of the first DOOM.

Hell is the demon’s home, and the Marine’s incursions bring both swarms of fearsome monsters and a change in visual design denoting a departure from the human world. When the player first steps through one of the game’s hell portals, she finds herself in a landscape of jagged cliffs spiraling down to stone pits ringed with spikes and patrolled by snarling beasts. The sky swirls a nauseous ochre and the logic of human architecture is distorted. The only pathways are nonsensical routes navigated by jumping across floating rocks and running the bone-lined corridors of labyrinths.

The most familiar landmarks are twisted stone gates, which are quite regularly emblazoned with glowering busts of goat skulls, eyes staring down at the player in silent menace. In providing reference points from the natural world, id decorates its version of hell with the skeletons we leave behind in death and, to maintain a sense of pervasive dread, the skulls of goats. Even outside of its demonic enemies, DOOM marks the presence of evil with references to the animal.

///

As the New Testament built on the Old, Christian thought further entrenched the association of sinfulness with goats. The Gospel According to Matthew foretells the return of Christ on the Day of Judgment, describing “all the nations . . . gathered before him” (Matthew 25:32) before being separated into two groups. The next verse sees Jesus “. . . put the sheep on His right, and the goats on His left.” (25:33)

To the “sheep” Jesus says: “‘Come, you blessed of My Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.’” (25:34) And, to the “goats”: “‘Leave Me, you cursed ones, into the eternal fire which has been prepared for the devil and his angels.’” (25:41)

Sheep and goats are metaphorically distinct throughout much of the New Testament and nowhere is that clearer than in Matthew’s account of Judgment. The loyal sheep stands in for those who will be saved; the goat, on the other hand, is a stand-in for those who will be sentenced to eternal damnation.

As Christianity ascended to prominence in the 4th century CE Roman Empire, the symbolism of the New Testament became more literally tied to the image of the goat. Hellenist figures, like the forest-dwelling fauns and satyrs—especially Pan/Faunus—were goat-like in appearance, and closely associated with Dionysus/Bacchus, the god of wine and fertility who represented unbound, ecstatic thought, drunkenness, and sexual freedom. The influence of these figures—gods linked to an earthy sensuality opposed to the physical denial of Christianity—would go on to inspire associations with goats and sexuality in neopaganist Europe.

The end point of witch covens—groups of women frequently imagined to retreat into the wilderness, worshiping Satan in the guise of a Pan-like goat—would last to the present day. Francisco Goya’s witch paintings, particularly the 1797-8 Witches’ Sabbath, are striking examples (as is 1797-8’s Witches’ Flight, directly referenced in The Witch’s final scene) of the form taken by the devil. Female sexuality, terrifying and necessary to repress in a staunchly patriarchal time and place, ends up mixing with Satanic worship and a renewed spiritual connection with nature in Western popular culture.

represented unbound, ecstatic thought, drunkenness, and sexual freedom

Combined with the following centuries’ rising interest in occultism, these depictions of goats would entrench the animal as an ominous figure. Throughout the approach to modernity, centuries of Christian thought were repurposed in an era defined by a mixture of rationalist, romanticist, and transcendentalist exploration. The scapegoat of Judeo-Christian scripture found itself a focal point for pagan worship as Pan and occult spirituality as the Eliphas Lévi-drawn Sabbatic Goat and Aleister Crowley-worshiped Baphomet. Its current symbolism as a recurring figurehead for the oppositional practices of Satanists shows its enduring power.

///

The goat is a perfectly nice animal. It’s intelligent, friendly, and, as a cornerstone of human agriculture, has provided us with milk and cheese, mohair to make clothes, and help with clearing land and transporting goods. Just the same, the goat has been historically maligned for long enough that its place in Western popular culture is defined not by affection, but a fear cultivated to the point of instinct.

In The Witch, Black Phillip is, taken on his own terms, adorable and a possible source of comfort in hard times. Viewed by the film’s 17th century Puritans, though, Phillip absorbs centuries of mythological association to become something much more frightening. In DOOM, the goat similarly embodies our fears, the physical characteristics of an unassuming animal used as cultural shorthand to create demons that the player can shoot and rip into piles of gore without a sense of guilt.

In both cases, goats become something far more than animal. They, like the ancient scapegoat, are burdened with metaphysical traits—sin, terror, evil—that humans must find a place for. They become monsters and demons, removed from the natural world to carry the weight of concepts that are often too dark and too difficult for humans to wrestle with on our own.

Header image: San Michele al Pozzo Bianco

The post The Goat, the Devil, and DOOM appeared first on Kill Screen.

August 2, 2016

A videogame tribute to growing up around the Yugoslav Wars

Ivan Notaros appears in Issue 9 of Kill Screen’s print magazine. It launches on August 8th, but you can get 10 percent off before that date with the discount code RELAUNCH.

///

Ivan Notaros is constantly flooded with new game ideas. It’s the result of endlessly tinkering with videogame physics and art styles, letting his curiosity spill out onto his humming computer—each click of the mouse could result in another potential candidate. In my time speaking to him over the past few months for Issue 9 of Kill Screen‘s print magazine, he has released one game, dropped work on a larger one, started a collaborative project, and returned to another game that he started making two years ago.

The latter is the one that Notaros pitched to Stugan, the two-month program that brings a handful of game creators to the quiet Swedish woods to focus on building the game of their dreams. Notaros, and his game House of Flowers, were one of the pairs accepted into Stugan this year. And so, right now, and until August 27th, he’s miles away from the nearest town, batting away all the other game ideas that crowd his head to instead focus on this single one. Fortunately, it’s a game that means a lot to him. That should help.

House of Flowers started out life as a low-poly, pixel art diorama of a truck on a road. Something about it struck Notaros as being quite Serbian. Being from Belgrade, Serbia himself, perhaps Notaros’s impression here isn’t too surprising. In any case, he stuck with this diorama a little longer, adding the ability to drive the truck, to walk around the scene, to carry things. It was mundane; practically a simulation of loading up a delivery truck. But in this dull normalcy, Notaros saw the potential to tell a story that he had personally become bored of repeating to the people he met.

“I think I always wanted to tell a story about the 90s in this region and the breakup of Yugoslavia,” Notaros told me. “Whenever I traveled, people kept asking me to retell what really happened in the wars, so I grew tired of repeating the same story. I mean, I was always explaining the war as something where everybody is guilty, where the core human values are the main factor of how things [turned] out, rather than a political entity or an officer or a powerful individual.”

Notaros grew up with these conflicts

The wars Notaros refers to are the Yugoslav Wars, which kicked off in 1991 and continued as a series of separate but related military conflicts until 2001. They were, in fact, the first European conflicts since World War II to be deemed genocidal in character, due to claims of ethnic cleansing between Albanians and Serbs. The result was the break up of Yugoslavia’s former republics, with Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovenia, and Serbia all becoming independent countries.

Notaros grew up with these conflicts, and also watched his parents deal with the difficulties they brought, including economic decline. His first-hand experience with the wars is what leads him to recount them from the perspective of a “normal person,” i.e. himself. He is close enough to the wars to know them in detail, but also distant enough to avoid pinning the blame for them on any individual person or group—his argument is that the cause is an issue that’s bigger than any single entity, it’s rooted in humanity itself.

Given that humanity’s darker side is Notaros’s focus, and this is something we can all understand, he is able to tell the story of what happened during his youth in a way that anyone can relate to, without the need for them to be familiar with Yugoslavian politics. That’s the potential he saw in that simple diorama with the truck. Interacting with the truck looked and felt Serbian to him while also being straightforward enough that anyone should be able to get what to do. With this as a starting point, Notaros started to build a bigger world around that central truck, one that would become a “love letter to [his] home.” As he says in his pitch to Stugan, House of Flowers isn’t so much a game about a war, but the effects of a war in the parts of a country where it didn’t directly take place.

The task in House of Flowers is to get by. You work with industrial machines as part of low-paying jobs that hurt more and more as the economic crisis worsens. Other aspects that Notaros saw during his childhood also play out, including: the decline of communist values, the rise of nationalism, the increase of crime and corruption, and the introduction of conscription. “The story is not a historical reenactment,” Notaros says in his Stugan pitch, “rather it’s the story of what led to the society I live in today.” That said, Notaros is taking directly from his own memories, picking out specific music, smells, sounds, and people that he recalls from the time and putting it all into the game.

House of Flowers is currently in development for PC. You can find Notaros’s games on itch.io.

The post A videogame tribute to growing up around the Yugoslav Wars appeared first on Kill Screen.

Ugly embraces broken computer animation to tell its story

The progress of computer graphics often seems like a long race towards photo-realism and precise, natural movements meant to mimic the world as we see it. But there are projects that seek to show the world as we feel it, and when an artist has that in mind, you end up with works similar to Nikita Diakur’s upcoming short film Ugly.

Sourced from an internet story posted by an anonymous writer, Ugly will follow a Native American Chief and an Ugly Cat (the titular “Ugly”) as they try to find peace in a destructive neighborhood. Apart from the story, the most distinct aspect of the film is that it’s shot with a unique style of digital puppetry, which is an effect that has to be seen in motion—describing it with words just ain’t gonna cut it. Your best place to see it in action is the video below, taken straight from the Kickstarter page.

“Since being in control is often an illusion, we decided to give up on it,” writes Diakur. “As a result, the animation in Ugly is somewhat different than what you’d normally expect from a Computer Generated film.”

perfection isn’t necessary here

The technique used here is a combination of puppeteering and dynamic simulations, which Diakur says “is both hyper-realistic and imperfect,” which it is considered goes well with the main theme of Ugly. He’s not wrong. The animations are broken and stilted, and filmed in one take—perfection isn’t necessary here. By not constraining the motions of the character through traditional animation means, the director is allowing for an oddly more naturalistic approach to computer graphics. There are no in-between poses, no breaks in the programmed animation, so if a puppet falls down the stairs, it does so as its originally planned to do.

The effect is a bit like a malfunctioning puppet show, but it’s easy to focus on that rather than the fact that the effect is actually straight-up pleasing. The film showcases a digital world meshed with a sort of imprecise hyper realism that verges on just the right side of wrong. Early GIFs show Redbear, the Native American Chief, smoking a cigarette as the sun rises, and a video of a bike passing through a car park shows off some of the beauty and madcap goings-on that can happen with this style of filmmaking.

You can follow regular updates through the Kickstarter page as the filmmakers finish work on Ugly.

The post Ugly embraces broken computer animation to tell its story appeared first on Kill Screen.

On Rusty Trails, a videogame about the absurdity of racial prejudice

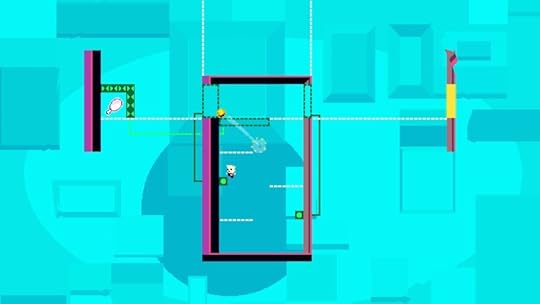

While On Rusty Trails may look like yet another 2D platformer at first, its creators at Black Pants Studio took it beyond that simplistic impression by enabling a discussion about race through the game’s primary mechanic.

“It was one of those days where I read the newspaper and there was an article about guys beating up people for having the wrong skin color,” said Tobias Bilgeri, the game’s designer. “I read another article where a German politician said: we do our best, but the people who come to us have to integrate themselves. Then I thought, even if they eat bratwurst, drink German beer and sing German songs, there will always be people who won’t agree that they are part of us, just because of their appearance.”

“It shows the absurdity of racism”

This is when Bilgeri came up with the idea that motivated the creation of On Rusty Trails: “what would it be like if everybody had a suit, which could change their appearance within the blink of an eye. Would that be a solution?”

This somewhat crude approach to the topic delivered the “Switchy Suit.” It’s a suit that lets the main character of On Rusty Trails change his color between the rust-red that lets him live comfortably at home, and the ocean-blue that lets him fit in among the sea-dwellers that make up the other half of the world’s population. Changing colors is essential to progress in different areas, and you’ll be able to avoid environmental hazards and walk on different platforms depending on which color you currently are.

It’s a simplistic approach but it’s intended to be. The simplicity with which you can adapt to a situation, simply by using the Switchy Suit to change to the right color, is designed to highlight how ridiculous prejudice really is. “Some things are easier if you have the ‘right’ gender, skin color, religion etc. in the right situation, while other things become impossible,” said Bilgeri. “In the game you can feel this every time you use your suit. Some things will work, some people will be nice to you, but others who were your friends just a second ago, will instantly start to bully or even attack you. It shows the absurdity of racism.”

Can a tiny platforming triangle teach players about the petty systems that inform racism? Maybe, maybe not: the key thing for Bilgeri is that talking about inequality in more places increases the chance people will take notice, and that can’t be a bad thing.

On Rusty Trails released in June for PC on Steam, GOG, and itch.io. It’s being exhibited as part of the innovation showcase at GDC Europe 2016.

The post On Rusty Trails, a videogame about the absurdity of racial prejudice appeared first on Kill Screen.

A kingdom management game in the style of Tinder

You’ll know how addictive swiping can be if you’ve ever downloaded Tinder. Yes, the dating app does encourage you to be shallow (like, really shallow), but the simple choice of swipe-left or swipe-right really speeds you through prospective dates. It’s the appeal of quick decisions and minimal complexity, save the occasional tap to see more photos or—if the semi-anonymous subject is really lucky—the coveted (read: creepy) SuperLike.

To some extent, Tinder has the same appeal as endless runners—swipe-up, swipe-down—in its repetition, though it trades leaping between buildings for leaping between college guys who think salmon shorts make them look slick. Though the comparison to endless runners may soon become out of date as it seems the creators of Tinder have accidentally encouraged game designers to borrow that swipe and do something bigger with it.

mashes up Tinder’s satisfying swiping with something a bit more surprising

Enter Reigns, an upcoming mobile title that mashes up Tinder’s satisfying swiping with something a bit more surprising: the monarchy. Reigns, like the title suggests, is about being a king. This king in particular has a lot of decisions to make. That’s where the swiping mechanic comes in: you swipe cards left or right to decide how to legislate your kingdom. Through this simple action, you are able to moderate warring factions, keep your people happy, and most importantly, solidify your rule.

In some situations the cards resemble something more like a text-adventure game (kick the door/open the door), but in other instances you’re making huge decisions that impact everyone under your rule, all with the flick of one royal finger.

Since failure to appease the masses means the king is out, the end goal of Reigns is to create a lasting dynasty. Though one monarch may get beheaded for pulling a Marie Antoinette and letting them eat cake, his heir can swoop in and try to pick up the pieces. The task of balancing such volatile factors is best experienced in the long-term, and some effects will echo through generations—another charming example of old people ruining it for the rest of us. If Granddad Louis 6.5 was a beloved sovereign all the better, but if not, you’re on your own.

Reigns is already getting attention: it was shortlisted for “Use of Narrative” at the Develop Awards 2016 alongside the likes of The Witcher 3 (2015) and Her Story (2015), and has been showcased at festivals such as Game Happens, Feral Vector, and Now Play This. Don’t worry, you won’t have to wait long for your own micro-kingdom. Reigns will be out August 11th.

Reigns will be available on iOS, Android, and Steam.

The post A kingdom management game in the style of Tinder appeared first on Kill Screen.

HackyZack is about living with anxiety, but you probably won’t realize

HackyZack is a “shitty metaphor” for creator Zack Bell’s thoughts and feelings on his own past. (“Shitty metaphor” is his phrasing, by the way.) It takes a Super Meat Boy (2010) approach to platforming—its meaning abstracted and then scattered among undeniably crisp platforming challenges. But where it differentiates from other platformers is in its multitasking. In HackyZack, players have to bounce around a plethora of obstacles all while maneuvering different balls to a goalpost.

So let’s get to it: HackyZack is about living with social anxiety—trying to escape its grasp by imprinting it onto a person or object that simulates comfort and security. For HackyZack’s little sprite, the balls are the only way to “win and survive.” Though like the people we cling to for comfort—whether it’s unhealthy or not—the balls are never things the player can directly control. These themes started to emerge organically once Bell started developing the game. “When I analyzed all of the mechanics, the settings, and the mood, I could easily pick out parallels between the game and my past,” he said. Now, most of the mechanics—and not only the balls—are tied to the underlying narrative.

“I could easily pick out parallels between the game and my past.”

“For example, the theme of World 4 is expectations. The portals in that area represent pushing unrealistic expectations on your partner; often feeling like you need to be in two places at once,” Bell said. “World 5 is about manipulation. This is where we introduce the Voodoo Ball, and when kicked, it has an identical effect on all other balls on screen.”

Those only interested in the surface-level challenge of Bell’s precision puzzle platformer won’t feel bogged down by the personal themes, though. The personal elements of HackyZack were originally just for him: “It’s something that I’ve been holding on to,” Bell added. In a way, the game represents a way for Bell to put closure to his past.

Bell ultimately wants folks to have fun with the game, and if that means digging deeper to explore Bell’s personal relationships and social anxiety, then it’ll be there to explore. Those looking for answers will find them. On the other hand, those unconcerned with any concealed theme likely won’t notice any darker meaning. “The game will be fun and stand on its own, without the psychological undertones,” Bell added.

HackyZack is expected to come to Windows, Mac, and Linux during the first half of September. More information on a possible console port will come soon. Find more information on the game on its Steam page.

The post HackyZack is about living with anxiety, but you probably won’t realize appeared first on Kill Screen.

Anthrotari explores growing up as a queer furry in the ‘90s

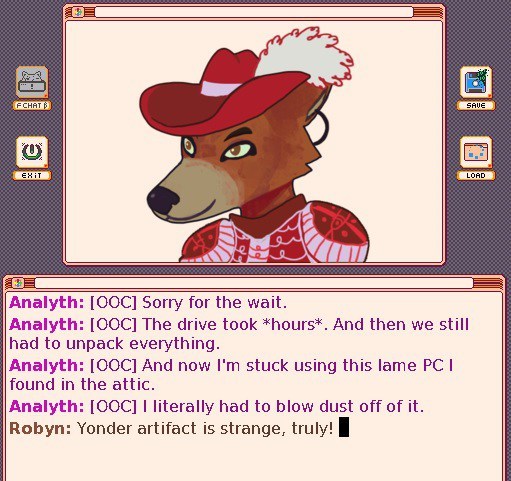

Dial-up modems, Windows 95 floppies, IRC channels, and free American Online disks. Ask anyone who lived through the internet boom of the ‘90s and these are guaranteed to be some of the first things that come to mind. But for New York-based game developer J.C. Holder, who uses they/them pronouns, there was another aspect of their identity that marked growing up online: the anthropomorphic furry community.

Holder’s upcoming game, Anthrotari, is a visual novel that casts the player in the role of a furry roleplayer named Alex. Through IRC channels, Alex hangs out with a group of anthros across the nation—doing everything from traditional Dungeons & Dragons-esque roleplay, to flirting with other furries.

“If anything owes a lot to my personal experience, it’s the design of Alex, the player character,” Holder said. “Like them, I also grew up more on the internet than off it, discovered my first real community among furry roleplayers online, and spent a span of time in the woods mostly alone with a computer.”

Issues of belonging and loneliness are running themes

But Anthrotari is particularly interested in queer and trans roleplayers’ coming of age through the anthro identity. After all, nearly 20 years later, many queer members of the furry community built their first sense of belonging through anthro roleplaying. Holder looks to capture that through the wide range of character identities found in the game.

“Our cast of characters are all queer furries: they’re varying combinations of genderqueer, transgender, cisgender, gay, pansexual, and asexual,” Holder explained. “I’m fortunate enough to have enough experience with such identities, personally or through friends, to have made their respectful inclusion an approachable task.”

It doesn’t hurt, either, that the team is composed entirely of queer artists and designers, with Toronto developer Arielle Grimes producing the game’s UI, Little Teeth artist Rory Frances creating the game’s art assets, Emily Meo creating music and sound, and Lain Fairlight and Ellen McGrody working on writing and programming.

Anthrotari handles queer identities quite gracefully as well. Flirting happens naturally in the IRC, with Alex essentially surrounded by a cast of queer and trans furries to chat with. Issues of belonging and loneliness are running themes throughout each character’s route, too, as each of Alex’s friends cherish the time they spend together when they’re online. The game hopes to explore these questions of identity in more detail in the game’s full version.

Originally created for the second installment of the International Love Ultimatum game jam (or ILUJam) in June, the game’s early demo launched with hours to spare. Now that the jam is over, Holder and their team look to finish each game’s routes. But, if time and resources allow, the crew is also interested in expanding the game with more stories to explore. “There’s room for more and no end of other queer identities to represent,” Holder said.

In the meantime, feel free to check out the Anthrotari ILUJam demo on the game’s itch.io page. Players interested in supporting the game can do so through J.C. Holder’s Patreon, and there’s also a mailing list to stay updated with the game’s progress over at the official Anthrotari website.

The post Anthrotari explores growing up as a queer furry in the ‘90s appeared first on Kill Screen.

Don’t hesitate to dive into Abzû

When I try to picture what the ocean depths must have looked like near England’s Jurassic Coast, 300 million years ago, I picture something like Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889). I picture a space of stillness but also turbulent life, things moving ceaselessly in the restless dark; I picture everything swirling, vortices upon vortices.

What I picture undoubtedly derives from my encounters with what seems to have been the region’s primary resident: the ammonite, a snail-like prehistoric shellfish with a shell in the shape of a swirl. Ammonites were everywhere in this place. If you look hard enough, you can find their fossilized shells among the rocks under the muddy cliffs, engorged by pyrite or embedded in brittle clay. Ever since I found some myself, I’ve appreciated the ammonite for its unlikely dominance and aesthetic incongruity. On one end, an ugly little squid-like head; a head that looks primordial and amorphous and evolutionarily incomplete. On the other end: geometric perfection—something abstract, almost purely iconic, as impossible to improve as a mathematical truth.

I kept thinking about ammonites when I played through Abzû, probably because the game itself seems to take them very seriously. You first encounter just their shells, which constitute a kind of inscrutable collectible; there’s no way to tell how many you have, how many you need, or what purpose they will eventually serve. But then, not too far into the game, as you travel further and further into the explosively colorful ocean depths, you find more of them in various places. An ammonite painting adorns the walls of an ancient temple. An ammonite ghost, of sorts, floats idly above a city of spectral arches. You encounter them both alive and immortalized by reverent representation, alongside other creatures—the orca, the shark—that appear both ordinary and mythic, biological and theological, at the same time. The recurrence of the ammonite feels extremely purposeful, as though the game were reaching for symbolism—even totemism—in an old, lost sense.

Creatures appear both ordinary and mythic, biological and theological, at the same time

As you may have heard, Abzû is a lot like Journey (2012): it takes about 90 minutes to play, its aesthetic—developed by Journey’s art director Matt Nava—is the same kind of cel-shaded minimalism, it has a linear structure that nonetheless provides an illusion of expansive freedom, and it’s almost completely wordless. You play as an anonymous, androgynous diver, a figure very similar to Journey’s skinny Jawa, swimming purposefully—but not too purposefully—through a gorgeous ocean world that pops with color and light. The music soars alongside the diver’s acrobatic twirling; the strings get choppy and urgent when you enter a triumphant slipstream, propelled forward by other creatures. But it’s precisely these other creatures that make the game feel very different, in the way they’re anchored both to realism and to ideality.

The ‘animals’ in Journey were basically sentient magic carpets that you could ride around, more object-like than anything else. I don’t mean that as a criticism. I mean simply to point out that Journey’s overall interest in abstraction—in presenting a quest narrative with every constitutive element reduced to its barest essence—extends also to the fauna it presents, which appear almost exclusively as facilitators or enemies. The sea creatures in Abzû are facsimiles of real animals. They have lives beyond the player; they’re morphologically accurate, behaviorally unique; they have species names that appear in the bottom-right corner of the screen when you try to ride them, almost exactly like the car brands in Grand Theft Auto. Riding them isn’t really riding them: you cling like a child, gingerly, as they take you where they want to go. Take a break to “meditate” on one of the game’s meditation rocks and you can observe them from a distance, swimming in schools and occasionally eating each other—just being, by themselves, each in a different way. The game might be the best aquarium simulator ever made. Not that there’s a ton of competition.

At the same time, it’s as much about real animals as it is about spirit animals: animals as dreams, icons, symbols. It’s about animals that begin in flesh but have more power, somehow, as ideas, pitted against forces of a more human kind that exploit, overrun, and destroy. The basic plot is an eco-fantasy worthy of Captain Planet: at several points in the game, you encounter a blackened ocean cavern that you eventually revitalize with biodiversity. The cavern explodes with color—blue, orange, coral pink—then scores of different fish come bursting through the floor. A space ostensibly already filled with water fills with new water of a different kind, imbued with light. It’s hard not to see these moments of triumphant repopulation as fantasies engendered by the very real depopulation that plagues oceans across the world. Last September, the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London issued a joint report stating that, collectively, populations of fish species used by humans have decreased by over 50 percent since 1970. And yet, what’s surprising about the repopulations in Abzû is that they occur not through any kind of activism, nor through any kind of material intervention, but through trips to a world of spirits—a world of icons. An idea of an orca springs forth from a fountain of the mind; the cavern’s rebirth follows, but only afterwards. All the while, the ghostly ammonite reigns above.

The ideality of these animals raises a few big questions. Is Abzû about the ‘real’ ocean or a virtual one? Is it about literal ecosystemic problems we now face, or would it prefer to take us away from them? Is it a game that wants context or a game, like Journey, that wants to be self-enclosed? The answer is hard to pin down as the game is reticent by design. But it does seem to insist on the erasure of these binaries, suggesting a link between the virtual and the real, the aesthetic and the pragmatic, the iconic and the specific—a link, in other words, between the kind of purely aesthetic experience the game itself offers and real material problems in ocean ecosystems. Like Journey, Abzû is in some sense a game about archetypes and archetypicality, letting you dwell within and among them as though to remind you of their firm embeddedness at the foundation of other things. And yet, in a significant structural twist, it’s about recovering archetypes that no longer seem to have potency, rather than playing through an archetypal sequence—the Journey—that’s still going strong. And it proposes quietly, in its own weird and paradoxical way, that recovering these creatures as symbols might be a necessary step before we can rescue them from exploitation.

The basic plot is an eco-fantasy worthy of Captain Planet

Every year in Taiji, Japan, thousands of dolphins are slaughtered for their meat in a six-month hunting drive that stretches from early September to March. This local tradition was the subject of The Cove, a 2009 documentary that won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and has reportedly led—alongside a declining demand for the mercury-filled meat—to a significant decrease in the number of dolphins killed each year. But the hunt continues. 1,873 cetaceans (i.e. dolphins and whales) were slaughtered or captured during the 2015-2016 season. The animal activist organization Sea Shepherd, which first brought the Taiji hunts to international attention in 2003, has sent volunteers every year to keep watch over the hunts with copious pictures, video, and livestreaming. Because intervening in any other way would be a surefire way to get deported, the volunteers maintain a constant level of surveillance so that the dolphin hunters are forced to do their work under an elaborate series of tarps, thus making their killings with less efficiency. Sea Shepherd has no chance of stopping this “ecocide” in the short-term, only slowing it down. But it’s impossible not to see the blood that spills underneath those tarps, staining the water red.

The terrible actuality of this ongoing slaughter seems so far away from Abzû’s calming virtual ocean. But the game simulates a conceptual struggle that’s at the core of the conflict between the Taiji hunters and Sea Shepherd—a struggle between modes of seeing. One side sees the animals as little more than capital and biomass; the other is doing all that it can to remind viewers that they’re “sentient, socially complex cetaceans.” Sea Shepherd, like The Cove, has little agency over the pragmatic side of the fight—how many dolphins, how many whales. But the rhetorical side of the fight is crucial: convincing the international public to see these creatures as subjects rather than objects, destroyed by a regime of casual objectification that is itself rhetorical first and foremost. You have to be able to see dolphins as biomass before you can behave as though they are.

Vast schools of fish are a defining aesthetic feature of Abzû: schools of fish that swirl around you like clouds of colorful smoke; schools of fish so dense that they’re literally impossible to swim through, like giant boulders made of guppies. The game presents the diversity and vibrancy of ocean life through what amounts to extremely complex (and hypnotic) particle effects. And yet, at the same time, it never wants you to see its creatures solely as patterns, solely through a holistic, totalizing lens. It never wants you to see them as biomass. To ‘meditate’ means to regard them as individuals—not just individual species but individual fish. To rescue them is, before anything else, to transform them back into mythic icons, not just because reverence is an improvement over disregard but because it recovers something intrinsic to them that we need as much as they do. An otherness. A sacredness.

The ocean was a place of terror to the Victorians, before they tamed it with aquaria. It was still a space of mystery in the 20th century—always a metaphor for the unconscious in psychoanalysis, for that deep, dark place within us that we can never know—before it was tamed again by factory fishing, the SeaWorld aqua-entertainment industrial complex, and James Cameron’s quixotic quest to capture it all in 3D. The desire to make it a space of reason, control, and profit will never abate. But animal symbols remain embedded in the fabric of capitalism, even if they’re dormant. Ammonite shells adorn the shitty nautical bric-a-brac at HomeGoods and TJ Maxx. The last time I saw that shape, it was on a shower curtain hook at Bed Bath & Beyond. The creature is long dead. But the form, that perfect form, somehow makes insistent, implacable demands.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, who believed that totemism was at the base of every culture, including Western modernity, once said that animals are “good to think with.” Abzû makes the audacious suggestion that thinking with them differently, reverently, is the only way to set them free.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Don’t hesitate to dive into Abzû appeared first on Kill Screen.

August 1, 2016

A Wolverine game from 1994 did grime music before it was cool

Producer and DJ Sir Pixalot has rediscovered what is perhaps the first “grime” instrumental piece in the boss track from the 1994 SNES game Wolverine: Adamantium Rage.

Grime is a genre of music that finds its origins in East-London from the early 2000s. The birth of the genre can be found in some rap albums, the lyrics of UK garage music, as well as the thumping rhythms of dancehall and early electronic music. However, this track from 1994—a full eight years before the birth of the genre according to FACT—is throwing a curveball into music history.

It seems as though Dylan Beale, the creator of the Wolverine: Adamantium Rage soundtrack, was influenced by many of the same genres of music that ultimately created grime, including jungle and classic hip-hop sounds. But the primary factor in creating this unintentional precursor to the genre was size.

Sir Pixalot has already turned it into a proper grime track

Classically, videogame music is an exercise in restrictions. Cartridges for the NES varied in size—coming in at under 48MB (at their largest)—with most of the memory going towards coding and art, there wasn’t a lot of room left over for music. Beale was given just 200KB of space in which to craft the entire soundtrack to the Wolverine game, from hip-hop infused levels to the jungle and hardcore tinged boss-battles. To save space on the final disk, the composer had to whittle away the highs and lows and bring them down to their grungy final resting place. Infused with the electronic beat, you can see the same exposed roots that made their way into grime.

The Wolverine soundtrack does have the catchy arcade sound that defined the games of the ’90s, which might lead some to doubt the discovery of grime here. To those I say, hey, roll with it a little, it’s not like many other secret sub-genres are found half a decade before their time. And in any case, Sir Pixalot has already turned it into a proper grime track with a dub with vocal from J-Wing. The rest of the soundtrack from Adamantium Rage sounds a bit more like the hip-hop infused arcade hits from the era along with some of the orchestral hits that you can catch in the grime boss track.

Listen to the full Wolverine: Admantium Rage soundtrack right here. You can play the original game in your browser too.

The post A Wolverine game from 1994 did grime music before it was cool appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers