Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 78

August 8, 2016

Dutch videogame maker aims to confront his country’s colonial past

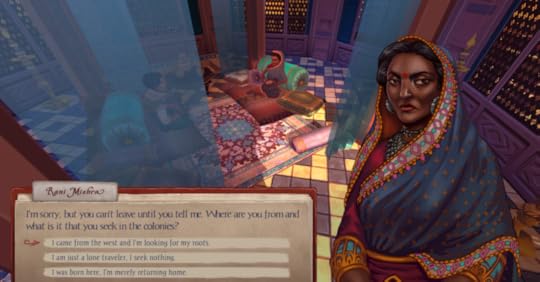

Herald’s narrative revolves largely around one question: How does your cultural heritage influence your identity? For many—including the point-and-click period drama’s protagonist, Devan Rensburg—it’s a complicated question, made even more complicated by the world’s history of colonialism. The “violent cultural clash” of colonialism plays a massive part in the complexity of the multiracial identity; and those complexities are what Herald aims to take on, through the eyes of the in-game ship’s (the HLV Herald) mixed-race steward.

Wispfire cites a certain urgency in putting out this game now, in this cultural climate. Race and immigration are at the forefront of many political conversations—including in the Netherlands, where Herald developer Wispfire is located. There, Geert Wilders, a far-right, anti-Islamic politician from the Netherlands, has influenced much of the conversation. Wilders was born of Dutch colonialism. His grandfather, “a high-ranking bureaucrat in the Dutch colony of Indonesia,” was more-or-less forced out of Indonesia when the country was decolonized. Anthropologist Lizzy van Leeuwen believes Wilders’ political leanings are defined by his Indonesian roots, of which he kept secret from the public for much of his life.

When development on Herald first began, Wilders was at the height of his political popularity; Dutch people were feeding off his anti-immigration narrative, following a surge of refugees seeking asylum in the nation. Not much has changed in the Netherlands since then: “anti-European Union and anti-immigration sentiments are getting increasingly popular, as more and more immigrants rush to find safety in the West, in wake of losing their homes, and in fear of losing their lives,” Wispfire’s Nick Witsel said.

Wispfire cites a certain urgency in putting out this game now, in this cultural climate

Like Devan Rensburg, Wilders’ ancestors operated in a space where they were neither one nor another, and van Leeuwen would suggest that underlying culture displacement is reason for Wilders’ anti-immigration platform. Wilders “operates in a post-colonial political dimensions, without it being recognized, says a lot about how the Netherlands dealt with, and still deals with the colonial past,” van Leeuwen said. “Keep quiet, deny, forget and look the other way have been the motto for decades. Because of that, no one could imagine that what happened in Indonesia 50 years ago could still have its impact on modern-day politics.”

The Netherlands’s own “freedom fighter” made his choice. As Herald’s Devan Rensburg, you’ll have to make yours, too. Developer Wispfire doesn’t want to keep quiet, deny, or forget the world’s colonial past—it wants you to be a part of it. It wants to simulate experience, and teach you “something about yourself and the world around you,” Witsel said.

Certain crew members aren’t tolerant of those who differ: “You, the player, can object to this intolerance from the start, and in doing so, forego any chance of having a peaceful relationship with [the crew member,] and in doing so, severely increase the chances that you and your friends will end up being canned,” Witsel said. On the other side, cooperating with the crew member opens up other opportunities—though in that case, “abiding by commands could lead to disdain” from other people of color on the ship.

“Many of the characters and conflicts found on board the Herald serve as metaphors for larger, timeless conflicts and ideologies,” he added. “It is through experiencing the consequences of your choices that you come to understand where many of these struggles and thoughts stem from.”

A playable Herald demo will available at the Indie Arena booth during gamescom 2016 in Cologne, Germany. You can pre-order the game on the Herald site.

The post Dutch videogame maker aims to confront his country’s colonial past appeared first on Kill Screen.

The videogame that will have you torturing Iraqi prisoners

Kaveh Waddell over at The Atlantic had the opportunity to interview the Pittsburgh-based designers working on a game that takes place in the infamous prison site of Camp Bucca, known for incubating a group of fighters who would later go on to form ISIS. According to the five designers (who remain anonymous because of the controversial nature of the game), the goal while designing this game is to give players the uncomfortable and up close experience of what occurred at the site.

The game doesn’t appear to have an official title, but is referred to many times as simply Camp Bucca. Still in development, it will have players assume the role of an American service member who is stationed at the Bucca detention center located in southeast Iraq. Throughout the game, players interact with prisoners dressed in yellow jumpsuits with the occasional black hood draped over their head to mask their faces.

time will tell how this game is going to be received by the public

Players will also be tasked with interrogating the prisoners—choosing methods of torture that range from waterboarding and electrocution to draw information from them. If the interrogation goes too far it will be possible to kill the prisoner. Players also have the assignment of moving prisoners around the camp, arranging them in cell blocks throughout the area. The developers relied on allegations of prisoner abuse in archived news articles and a leaked Red Cross report to guide their game design.

There is no video footage, extra screenshots, or further information on the game save for the content given to Waddell by the anonymous designers. It’s hard to have an informed opinion of Camp Bucca at this point. Torture has been used as a game mechanic in previous titles, but placing this in context of real-world events that are incredibly relevant is a bold move.

Making such a heavy statement about abuse and violence through an interactive medium like videogames may provide an experience that can’t be achieved anywhere else. But time will tell how this game is going to be received by the public. A lot of developers have tried (and failed) to explore violence and it will be interesting to see how Camp Bucca handles it.

To read Waddell’s interview at The Atlantic click here.

The post The videogame that will have you torturing Iraqi prisoners appeared first on Kill Screen.

Don’t care about the new Prey? That’s a mistake

Everyone seems to be a bit confused. Prey, the non-numbered reboot of the single-game “series” Prey (2006), has nothing to do with its own franchise. “Prey is not a sequel, it’s not a remake, it has no tie with the original,” confirmed director Raphael Colantonio, a week or so ago, in a video called “What is Prey?”. The video itself even has a miasma of confusion around it, with most commenters trying to understand the non-existent connections that might be in place. “Prey is what predator eat,” offers HearMeSoar, an answer that seems at least more logical than publisher Bethesda’s retooling of the name.

This confusion is warranted then, but after this last weekend’s Quakecon, and a new trailer, the game is coming into focus. And, unsurprisingly, Prey is seemingly a fundamentally different game to its predecessor. It can only be assumed that Bethesda are seeking to capitalize on whatever latent positivity the series name might carry in an effort to give what is essentially a new idea a jump start. This bizarre and confused maneuvering (was Prey even that notable of a franchise to begin with?) has cast something of a shadow over the game, one that suggests that, for many people, the question “what is Prey?” will remain unanswered for some time to come.

However, if we leave this confusion behind, the game that stands ahead with its tentative 2017 release date looks like an interesting proposition. A psychological thriller set in an extravagantly imagined 1960s space station, there are tones of Philip K. Dick to the issues of reality and identity it seeks to explore, and something of Dead Space to its terror and isolation. However, as Colantonio has stated, the game will also carry the hallmarks of developer Arkane Studios.

promise of a labyrinthine space station

As a game developer, Arkane is marked by its refusal to fall into the common paradigm of either artistic and narrative focus or mechanical and systemic depth. Its strength lies in the ability to straddle both camps, delivering rich artistic visions with multifaceted and malleable systems, as they did with Dishonored (2012). This style stems from co-founders and directors Colantonio and Harvey Smith, who between them were involved with the revolutionary games of Looking Glass Studios and Ion Storm, such as System Shock (1994), Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds (1993) and Deus Ex (2000). In many ways, this bloodline seems to be the true heritage of Prey. Its promise of a labyrinthine space station, RPG progression, narrative focus, and adaptable systemic gameplay suggests it’s as much a spiritual sequel to the likes of System Shock as BioShock. And as, over time, opinion of BioShock and BioShock Infinite’s (2013) compromised form begins to sour, perhaps Prey has the potential to reinvigorate a style of game design that is both rare and distinct.

Yet Prey is not only a revival. Even at this early stage Colantonio and Arkane seem to be proposing a development of their style, with a Metroid-like structure and a renewed sense of openness. Even their treatment of the protagonist, whose name Morgan was chosen to allow players a choice between a male and female avatar, suggests a progressive approach, and a welcome awareness of contemporary debates. It’s a promising first showing then, for this most confused of “reimaginings.” Let’s hope that despite being saddled with the deadweight of a franchise name, Prey is still able to establish an identity of its own.

The post Don’t care about the new Prey? That’s a mistake appeared first on Kill Screen.

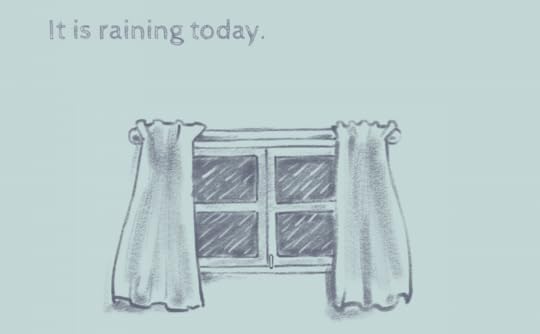

Rainy Day is a powerful and sobering look at anxiety

Rainy Day, a recent interactive narrative by Thais Weiller, is a quick and impactful glimpse of the paralyzing power of anxiety. It was born out of creative frustration when she moved from a design role to production, where she often stayed quiet about her own creative ideas so as not to disrupt the flow of her team. “I remember feeling as if I was silenced,” she said, “as if something was missing and I couldn’t say exactly what. Feeling that bad wasn’t particularly new to me a year back […] but feeling silenced was new.” She decided to try to cope with it in a medium that she felt comfortable with: games.

“people feel good in knowing that you’re not damaged goods”

Since she’s not a programmer, Weiller turned to Twine to tell her story. The game that grew out of it is anxiety-inducing but determinedly real, hitting a melancholy note of fruitlessness and frustration. Contributing to this feeling is her choice to blur text when the cursor is away, causing the choices to feel foggy and hesitant, and the ever-changing color of the background, which gets darker and harder to read as you progress. She says that player reaction was overwhelming, and justified her decision to post such a personal work, as people “feel good in knowing that you’re not alone in feeling like shit for long periods of time, that you’re not damaged goods.” The game doesn’t have any traditional happy endings, and that’s on purpose.

Above everything, Weiller said, was the feeling of guilt that she wanted to convey. Games have the unique opportunity to make you fail and take responsibility, which Weiller uses heavily in Rainy Day, as you try to get out of bed or make coffee or get dressed and find yourself incapable, over and over again. The inevitable feeling of resignation is one of the most powerful in Weiller’s own experience, and it can be translated to a game in a way not possible with film or writing. The effect is stark, as the game isn’t more than 10 minutes long but feels like it goes on for ages into the smaller and smaller concentric circles of depression.

In the end, what surprised Weiller the most was how many people cried while playing it. She doesn’t know if she should feel good or bad about that. “Just in case, I feel both,” she said.

Play Rainy Day over on itch.io .

The post Rainy Day is a powerful and sobering look at anxiety appeared first on Kill Screen.

New simulator lets you try to fix NYC’s crappy subway system

I’m not from New York, but even I know to avoid the 5. The largest rapid transit system in the world, New York City’s Subway links Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx to rush in workers from across the Tri-State area. Over 54 percent of New York’s citizens use the subway exclusively to commute. Millions depend on it for transportation, yet it’s been increasingly plagued by issues of sanitation, mechanical failure, and overcrowding.

Brand New Subway tasks you with improving NYC’s decaying subway system, while maintaining the delicate balance of cost and ridership. An intricately detailed experience, the game gives players more control over their urban planning endeavors than they ever could’ve hoped for. Stations can be placed almost anywhere, with lines intersecting every which way to lead them into the Big Apple. Using real census and transportation data, it estimates a given station’s ridership, while determining MetroCard fare based on the subway’s construction costs. Together, these numbers form a letter grade (NYC’s current system boasts a “B”), but bypassing that grade isn’t necessarily the goal.

https://killscreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/subway-game.mp4

Designed by J.P. Wright, Brand New Subway was submitted as an independent entry to Medium‘s “Power Broker” contest—honoring the Broker himself Robert Moses, the “master builder” of New York City’s now iconic subway system. Once a futuristic symbol of innovation, the nation’s aging rail systems are failing to hit the mark, as did its buses and roadways before it. It’s not uncommon for commuters in traffic to curse the names of the long-dead men who planned their cities. Many of America’s oldest metropolitan areas simply weren’t designed with enough foresight to accommodate modern means of transportation. Most cities, especially on the east coast, were purposefully designed to be confusing in order to hinder a British invasion. They were designed for horses and buggies and bikes—not Suburbans and hoverboards. Thus, many take issue when weaving through Boston’s many roundabouts, or New York’s paper-thin alleyways.

If you’ve ever played Sim City, you know that designing a public transportation system is not only arduous, it’s political. While, luckily, subways are generally convenient and extend far beyond city limits, at the end of the day they are built by for-profit companies. Metro rail systems often exacerbate the same accessibility issues that have existed since this country’s inception. For example, the effects of redlining are still apparent in many cities that are deeply segregated in all but name. In turn, these isolated low-income areas are often not deemed profitable enough to be given access to public transportation. Cities age and transform, gentrification spreads, and demographic shifts across neighborhoods.

Morality costs money

Morality costs money in urban development, and though Brand New Subway pretty much gives you free reign over where you place your stops, you’ll notice that extending them to far-reaching, isolated areas will demolish your cost efficiency. Maintaining high-traffic and often repugnant stops is bound to upset some, but the cash payoff is undeniable.

Brand New Subway also includes New York’s proposed plans for a subway overhaul. As the city aims to complete improvements by 2025, the game lets its users work for them—allowing thousands of users to give feedback, catch mistakes, and even suggest all-around more efficient routes. The beauty of Brand New Subway is that, in its simplicity, it bypasses bureaucracy and politics for immediate results. Transportation, especially in the public sector, is a juggling act of cost, convenience, resources, and politics. Brand New Subway is an intricate tool that, after a few rounds, almost makes you miss the chaos.

Check out Brand New Subway here, along with creator J.P. Wright’s other endeavors in engineering.

The post New simulator lets you try to fix NYC’s crappy subway system appeared first on Kill Screen.

You can crash land on Pan-Pan’s pretty planet later this month

A pan-pan is a distress signal; it’s not as serious as a mayday call—your life is not likely in immediate danger—but, uh, something’s definitely wrong with your aircraft. It’s customary to call it out three times. Pan-pan, pan-pan, pan-pan.

In Spelkraft and Might and Delight’s Pan-Pan, your ice cream cone of a ship crashes onto a strange planet. A strange planet, but a lovely one, at that—Pan-Pan seems to take an aesthetic cue from ustwo’s Monument Valley (2014). There are loads of candy-colored buildings to explore, and quite a few locals to help you find your way around.

a game you may want to linger in for a while

A trailer released on August 4th shows exactly how you’ll fix your ship and get back to the planet from which you’ve come: puzzles.

You’ll have to solve lots and lots of environmental puzzles, all while exploring Pan-Pan’s lush open world. The way in which you solve these puzzles is totally up to you; there’s not one linear path to your home—there’s no rush. Set to an ambient soundtrack by Simon Viklund, the sound director and composer for Payday 2 (2013), Pan-Pan feels like a game you may want to linger in for a while. After all, your life isn’t in any immediate danger.

Pan-Pan’s pretty puzzles will be released on PC on August 25. Check out its Steam page for more information.

The post You can crash land on Pan-Pan’s pretty planet later this month appeared first on Kill Screen.

Necropolis couldn’t entertain the dead

How’d dungeons get so big, anyway? Before fantasy games, dungeons were modest medieval cells or imprisonment-themed sex rooms. But in today’s post-D&D RPGs the dungeon might as well be the cornerstone of the universe. Any tough mazey place becomes a dungeon: labyrinths, catacombs, mines, caves, mansions, factories, and even spaceships are called dungeons if there’s someone with three health bars and a pot of gold inside. It’s understood that the Forest Temple in Ocarina of Time (1998) is a dungeon, Rise’s mind in Persona 4 (2008) is a dungeon, and Karazhan in World of Warcraft (2004) is a dungeon, though none of them are actually dungeons. (OED: “A strong close cell; a dark subterranean place of confinement; a deep dark vault.”) A game dungeon can be a unit of time, a container for a theme, or a system of education. Often the only prisoner inside is the player.

I wasn’t around for the primordial game dungeons of the early ‘80s, so for me the definitive crawl was not through Rogue (1980) or Wizardry (1980) but down into the ugly rhizomes below Daggerfall (1996). If you never played the game, imagine a version of No Man’s Sky that ran on a 486 and modeled Hell instead of outer space. Instead of exploring the universe you got lost in holes. Hundreds of oversized subterranean labyrinths hid quest items in random corners behind skeletons that howled like they were more scared of you than you were of them. Pixel grunge made every visible part of the game drip into every other part, and the 3D automap looked like a picnic basket covered in ants.

The Daggerfall section of the Elder Scrolls wiki notes dryly that “even the least of the random dungeons are logically too large for the majority of quests.” The Hints page advises following the “right hand wall method” of sticking to the dungeon’s rightmost edge and hoping to find the quest item along the way. If this fails, it proposes the “left hand wall” method. I don’t remember holding to either method as a kid. Instead I would rush into the heart of the maze and get terrifyingly lost, abandon all hope of finishing the quest, and run down the same blind alleys again and again in search of the exit. Sometimes I would resort to the “create new character” method. And so a few of Daggerfall’s save slots became cells for adventurers trapped underground forever, making an honest dungeon out of those warrens at last.

Necropolis, a deeply unlovable new dungeon crawl, is no Daggerfall. But for a minute it took me back. After clearing a few levels of the game’s one dungeon—a roguelike-like experience with Dark Souls-lite-like combat—a friend and I descended to a floor that could have fit every earlier area inside itself. It stitched together all the game’s biomes with no apparent plan, joining vaulted corridors, moving walkways, steam tunnels, swamps, and thin mountainous paths. Like every level, it had no map. Like every level, it was occupied by slow-moving creatures who didn’t rise to even an MMO player’s expectation of monster intelligence, who would single-mindedly chase after Player 1 as Player 2 stabbed them to death from behind. Like every level, it was “low-poly,” which in Necropolis also means low-detail and low-interest: the sort of blank geometry that’s fine to rush past in Race the Sun (2013) but miserable to hike over on foot. And like every level it was littered with dozens of copies of the same few useless weapons, each summoning the same “funny” pop-up as you approach, e.g. “When choosing between this ‘weapon’ and let’s say, a rabbit; a rabbit’s more useful in combat.”

I did eventually find a cluster of rare items on the ground when my friend threw all his equipment down and said he was never playing Necropolis again. This brought on a wave of nostalgia. It felt for a second like the old Daggerfall magic had returned, crushing yet another adventurer with an unforgiving, intolerably huge dungeon. But I was really watching something simpler: the timely rejection of an awful game by someone who wasn’t doomed to finish it for the sake of a review.

Necropolis stands out for its lack of imagination

That one stupidly big floor was the only real hint of personality in Necropolis, and it was an illusion. The levels that followed (nine in total) were shorter and easier and made of the same parts. The whole game is more or less solved once you learn how to kill the first enemy (circle with shield raised and then strike, like the world’s dullest Dark Souls player) and dodge the first trap (jump). As you gather invisibility and invincibility potions you start to stomp carelessly through crowded areas that once required a bit of care. My original character died in minutes, trading swipes with an undead warrior in my introduction to the game’s listless underwater brawls. My second character beat Necropolis.

You can see why the game had to be easy: it’s so plainly joyless that anyone who dies midway through will probably uninstall rather than make the long walk back down. You’ll find nothing but the same drab walls and kooky item descriptions, repeating floor after floor, getting “funnier” every time. The same clicking bomb-rodents will jump out of thin air behind you and blow up while you’re trying to use the crafting menu, forcing you to reopen that same menu to brew a new health potion, giving another bomber time to pop out and scuttle over the stones behind you….

In the annals of dungeoneering, Necropolis stands out for its lack of imagination. The strange caprice of Daggerfall’s dungeons gave its world character—dread of those underground spaces (more horror than fantasy, as Adam Smith once wrote) shaped your behavior in the lands above. And these days the world is teeming with dungeons that boldly assert their identity, from the punchy bullet hell of Enter the Gungeon to the mutant-filled wastelands of Caves of Qud (2015) and the Doomy corridors of Teleglitch (2013). With no character of its own to speak of, Necropolis is defined by what it lacks: true builds, classes, bosses (there’s one, but he won’t impress anybody), deities, rare events, articulate combat, narrative hooks. Why even keep permadeath when you cut out all the variation that makes restarting tolerable?

If Necropolis has one thing going for it, it’s the scrupulously accurate title, a rarity in a genre of questionable “dungeons.” Its halls are indeed inhabited by skeletons and rotting things, in sufficient numbers (1,008 monsters killed, according to the victory screen) to constitute a city or at least village of the dead. This settlement will expand, according to an apologetic post from the developers, with new enemies, new places, and retuned combat. I hope things do get better, but as it stands there are a few hundred other games I’d crawl through before coming back to this one.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Necropolis couldn’t entertain the dead appeared first on Kill Screen.

August 6, 2016

Weekend Reading: I Want Tomorrow Like Yesterday

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Where Is the New Cyberfeminism?, Cecilia D’Anastasio, The Nation

Every major step forward in the technological and philosophical landscape for the last few generations has had a major feminist response to it. Cecilia D’Anastasio wonders who will pick up the torch of the likes of Sadie Plant as culture dips its toes into the new realm of virtual reality.

Why I love my possessions as a mirror and a gallery of me, Lee Randall, Aeon

There is a contention to owning a ton of crap. Artistic and literary traditions to imagine one’s self as independent of their choices as a consumer or collector. Nuts to that, says Lee Randall, who has written an essay about loving the profile created through the things in their flat.

Photo belongs to Lee Randall

Towards an Art History for Videogames, Lana Polansky, Rhizome

All is thankfully quiet on the “games vs art” front, but that doesn’t pull away from the fact that the majority of games’s developing history belongs to the technological and commercial worlds. That weight and perspective makes an interesting conundrum on how we decide to address games’s art history, and Lana Polansky explores some pockets of subversion.

How Vector Space Mathematics Reveals the Hidden Sexism in Language, MIT Technology Review

Listen, just because French as a language decided it’d be efficient to gender different kinds of condiments doesn’t mean you should get too smug by comparison. For example: researchers have discovered that the Word2vec, a massive data set on language and word associations, is eerily sexist, bundling terms like “mother” and “woman” to “nurse” and “homemaker” like an AI from Pleasantville. The MIT Technology Review reports how the researchers who stumbled on to this plan to fix sexism. On a mathematical scale, anyway.

The post Weekend Reading: I Want Tomorrow Like Yesterday appeared first on Kill Screen.

August 5, 2016

Schlong is just like Pong, but with 100% more dicks

Needless to say, this article is NSFW.

///

This is a difficult question to ask, so I’m just going to go ahead and get right to the meat of it. Have you ever been playing Pong (1972) and wished that, instead of the rigid paddles, you could get something a little more floppy in your hands?

Schlong could have you covered. Created by Dillon Sommerville, Schlong replaces both player’s paddles in a traditional game of Pong with erect but surprisingly flexible penises, flopping around the place with the aim of deflecting a ball back at the opponent’s goal. That’s all there is to it. You know what Pong looks like: bright white lines on a blackboard, a white dot moving across the screen. Now imagine that, but with dicks. There’s a GIF here, take a look:

It wasn’t always supposed to be this way. Sommerville began by working on a local-multiplayer sports game called Hock at the start of this year. Hock is a fast-paced twin-stick game with a ’70s aesthetic. “In the midst of that and working full-time as a 3D environment artist, I was getting pretty down about not being able to put out content regularly,” said Sommerville. “I went out drinking with coworkers and we got talking about making ‘Pong with dong’ and, since I’d already put all this work into the physics of Hock, Schlong was easy.”

Schlong seems to inhabit a totally different world to Hock‘s futuristic approach, but there’s a certain appeal to using the swing of the, well, dong to catch the ball. There’s something reminiscent of Push Me, Pull You to the game’s aesthetic. Oh, and it should go without mentioning that it bears many resemblances to Genital Jousting.

“make it floppy”

But, if Hock is a serious sports title, what of Schlong? “I think in game design, floppy physics definitely succeed best when they’re attached to a really minimal gameplay scenario,” said Sommerville. “The more non-aesthetic features, the more weirdly competitive it becomes. Although, I think I’ve learned that when you’re making a sports game and you’re not sure about the physics,” Sommerville pauses, “make it floppy.”

Sommerville, who goes by the handle Handwiches on the TigSource forums, has cataloged a lot of his thoughts and more than a few NSFW GIFs in a forum thread that you can check out here to examine more of his process. Or, you know, if you just wanna see more dicks flopping around. Whatever suits you.

You can visit Schlong’s itch.io page to get it for the low low price of however much you’re willing to pay.

The post Schlong is just like Pong, but with 100% more dicks appeared first on Kill Screen.

Power Drill Massacre brings grindhouse horror to videogames

From It Follows (2015) to Netflix’s Stranger Things, the themes and style of ’80s horror are slowly but surely making a comeback. So perhaps it’s no surprise that such inspirations are appearing among games as well, with the once-colossal genre of slasher movies influencing titles like Lakeview Cabin Collection, Until Dawn (2015), Dead Till Daylight, and the upcoming Friday the 13th. The works of developer Puppet Combo wears such inspirations on its sleeve.

I recently had the pleasure of enjoying the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) for the first time last week, and realized what made the movie such a revered classic, from the abrupt reveal of its iconic skin-wearing killer and its moment of terror in broad daylight, to the disturbingly claustrophobic madness during its dinner scene. There’s a raw texture to the horror, divorced from the slick style of modern films in the genre. It’s that kind of tone and atmosphere that Puppet Combo hopes to capture in his roster of horror games—including the latest, Power Drill Massacre.

The equivalent of grimy gaming grindhouse

“I love how early 3D games look (especially horror games) in the same way that I love how shot on video movies look. 555, Sledgehammer, Spine, Video Violence, Las Vegas Bloodbath wouldn’t feel the same if they were shot on film”, states the creator of Power Drill Massacre as he explains the rationale behind his early-PlayStation-style visuals—the kind of graphics that brought the original Silent Hill (1999) and Clock Tower (1999) to life. The low-poly aesthetic acts as the equivalent of grimy gaming grindhouse.

Power Drill Massacre hearkens to the terrified teens and isolated woodlands cabin of Texas Chain Saw Massacre, as a masked killer stalks and slaughters a group of teenagers through a gauntlet of forest and labyrinthine corridors. Like those aforementioned titles, it’s a game of panicked escapes and tense pursuit by a relentless psycho.

Texas Chainsaw Massacre isn’t the only classic horror movie influencing Puppet Combo’s work. In game jam entry Babysitter Bloodbath, a young woman flees her home from a knife-wielding masked killer in a clear analog to Halloween (1978). And in the months to come, the developer will be working on Splatter Camp, a larger-scale project set in and around a summer camp stalked by a psychopath.

Splatter Camp and Power Drill Massacre are actually inexorably linked projects, as Puppet Combo uses the latter to master Unity to complete the former. “I need to learn C#, get some Unity experience, and rebuild my code library by making a simpler game than Splatter Camp. And that’s what Power Drill Massacre is: a slasher game on a smaller scale. Splatter Camp will share Power Drill Massacre‘s code so you could say that they’re both in development at the same time.”

A demo of Power Drill Massacre is available to download for PC and Mac here. You can follow its development and Puppet Combo’s other projects through the developer’s website.

The post Power Drill Massacre brings grindhouse horror to videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers