Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 79

August 5, 2016

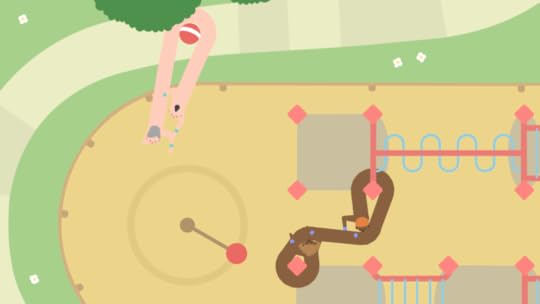

The physical intimacy of Push Me Pull You’s design

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

The multiplayer game Push Me Pull You builds a sense of community with the help of a bizarre but goofy premise. In a world populated by strange two-headed “sports monsters,” players must face off against each other in a friendly game of ball without getting too tangled in their own bodies. Despite the odd (or slightly queasy) concept, Push Me Pull You draws players in with undeniable charm, creating a welcoming environment for people from all walks of life, regardless of age, race, or skill level.

Created by the small Melbourne studio House House, the game’s design hopes to bring players closer together—literally. Though a typical game includes four players, only two controllers can be used, requiring teammates get up close and personal. According to developer Michael McMaster, this was initially a practical decision designed to make sure the game was accessible to those with only two controllers.“(But) we realised pretty quickly that it introduced a strange new dynamic to the game,” he said. “When we exhibited the game at PAX East [expo] we opted to only connect two controllers, and it turned out great—lots of strangers ended up on teams together, and we ended up orchestrating a lot of funny, intimate experiences between players.”

Splitting the buttons of a single controller seems to embody the awkwardness of the game’s two-headed sports creature. Players can grow shrink, twist, and crawl with their half of the monster in whichever direction they choose, making it easy for teammates to get lost in the chaos. “It introduces a weird physical element to the gameplay, where players end up unknowingly gripping and twisting their shared controller as the game gets more intense,” said McMaster. “There’s this kind of subtle wrestling match happening alongside the much more explicit one onscreen.”

Through shouts of laughter, players struggle to get their individually operated heads working in the same direction

House House wanted players of all skill sets and experience levels to feel invited into the mayhem, embedding a sense of inclusivity and community into the game’s design. By allowing players to customise their sports-monster with a wide range of hairstyles and skin colours before each match, they created a world that everyone could imagine themselves in. “We wanted to reflect a kind of broad normalcy, where players weren’t playing as specific, named, or overdesigned characters,” said McMaster. “We needed to be inclusive in defining that normalcy. That’s why we feature pigtails, dorky bowl-cuts, mohawks and combovers—we wanted to [emphasise] that this sport wasn’t specific to any gender, age, or class.”

Part of the fun of Push Me Pull You derives from creating all kinds of wacky combinations and imagining the relationship between the two separate heads: a grandma attached at the hip to a nephew, or a punk rocker who gets dragged along by a middle-aged dad. Players of all kinds are not only encouraged to see themselves in the game, but also to discover their own enjoyment, fun, and strategies through the minimal structure. House House found that by giving players little in the way of formal instructions, it not only made the game more accessible, but also forced teammates to create their own unique ways of communicating. They watched how, in a single match, teams would develop an entire lexicon of short-hands to shout at each other in an attempt to bring order to the fleshy chaos on screen.

the fun of Push Me Pull You is getting entangled in a mess of human mayhem

The game’s launch trailer even revealed some of their favourite terms for the most successful techniques, like the “Poke” (when a creature pushes one of their heads into the opponent’s centre, using its ability to extend to drive it away). Each lexicon developed was not only unique to the players but unique to each team’s interpretation of the game world, reflective of how they made sense of the quirky surroundings. Before House House knew it, “we’d established a four-person competitive scene that felt incredibly personal and private,” said McMaster. “We love that we’ve made something that has this element of creative discovery at its core.”

Since the game’s release this past May, House House has seen Push Me Pull You played in a variety of settings, including even a few elementary schools around Australia. Designed to encourage mutual understanding and creativity through experimental play, the game carries a host of useful lessons for children in particular. According to Dr. Ian Lewis, a lecturer at the University of Tasmania and expert on learning through games, the multiplayer may appear to be all fun and games, but playing can help them develop important skills. “Push Me Pull You seems like a madcap bit of fun at first, but these sorts of games can be used in a structured way to start discussion about cooperation, communication, and what happens when those things are absent,” he said. Whether children or adults, though, part of the fun of Push Me Pull You is getting entangled in a mess of human mayhem.

The post The physical intimacy of Push Me Pull You’s design appeared first on Kill Screen.

John Darnielle’s next novel is a horror story about fragmented video tapes

In the music he writes for the Mountain Goats, John Darnielle tells intensely specific stories. One song describes a breakfast of boiled peanuts the morning a parther leaves for good. Another, from the band’s most recent album, Beat the Champ (2015), mournfully describes a wrestling match in which the loser has his head shaved with a “cheap electric razor from the Thrifty down the street.”

Darnielle’s first novel, Wolf in White Van (2014), is layered thick with references that situate it not just in a particular time or place, but inside a particular cultural niche, full of Conan the Barbarian comics and b-movie sci-fi. The main character Sean is drawn precisely with his internal monologue and with the media he submerges himself in. The story is fragmented, split between the past, the present, and excerpts from the impossibly exhaustive play-by-mail role-playing game Sean has designed.

There’s some kind of hidden threat now

Darnielle’s upcoming second novel is Universal Harvester, set in a video rental store in the last days of the age of video rental stores in rural Iowa. Six years after the death of his mother, teenage Jeremy works renting out movies. Eventually videotapes start coming back with short clips of hazy black-and-white footage recorded onto parts of them. These mass-produced tapes return manipulated ever so slightly by an unseen hand. Darnielle describes the novel as a “horror story that would also function as a cartography of grief.” Jeremy doesn’t necessarily want to be curious about the tapes, but it’s an absorbing mystery.

A horror story about videotapes is, of course, packed with its own references—not just to the movies mentioned in the story (the most popular tape spliced with hazy video is She’s All That (1999), the My Fair Lady (1965) adaptation starring Rachel Leigh Cook and Freddie Prinze Jr.), but also to other stories about the horrors hidden in images on tape. In Koji Suzuki’s 1991 novel Ring, a videotape serves as a vessel for a kind of digitized smallpox that passes from person to person as a representation of ghostly vengeance. The Poughkeepsie Tapes (2007) is a horror movie made up of a collection of videos shot by a serial killer. It’s graphic, and not the brooding exploration of grief Darnielle is looking to construct, but the heavy-breathing Jeremy hears on the tape and the slightly familiar empty barn he sees lead a reader to imagine the worst.

Or at least, something really weird, and nearby—adding an uncanny feeling of dread to the otherwise sunny Iowa plains. There’s some kind of hidden threat now, with the physical landscape and the tapes both contorted into new and unfamiliar realities. Where does this faulty reorganization of information—this glitch—come from? We’ll find out soon.

You can read the official announcement of Universal Harvester here. The book is available for pre-order now.

The post John Darnielle’s next novel is a horror story about fragmented video tapes appeared first on Kill Screen.

Climb a mystical mountain in a game based on Tibetan Buddhism

In Tibetan Buddhism, the space between death and rebirth is called bardo, a liminal period containing six—or four, depending on the source or scholar—different states, experienced in phases from birth to death to rebirth. This “limbo” is a journey in multiple senses, both to a spiritual conclusion and to a physical resurrection. British developer Blind Sky Studios explores this in-between space in Mandagon, a freeware game released earlier this week on Steam.

As detailed in a blog post, Mandagon was born as the personal project after one of the team members suffered a death in the family. The game shifted from being a garden variety collect-a-thon to a more environmentally-focused experience, with an emphasis on atmosphere and exploration. That’s when Mandagon was born.

Story, memory and other mortal things fall by the wayside

Despite having no connection, a couple of comments on Mandagon’s Steam page compare it to Fez (2012). I see where they’re coming from: the vertical pixel art has much of the same feel, as does the way the player character disappears into doors, the rooms beyond displayed as a dimly lit box on a black screen. Besides those surface similarities, though, they’re vastly different. Mandagon doesn’t bother with Fez’s 2D-to-3D gimmick, and nor does it hide narrative progress behind inaccessible puzzles. In fact, much of its appeal is in its calm. The full map is quickly accessible, the goal clearly laid out; what’s given to you is the journey.

Games that keep lots hidden encourage rushing, as the insatiable need for knowledge turns illuminating dark parts of the map into a kind of compulsion. The most beautiful game with the most intricate details can be unintentionally interrupted by a flashing quest marker or one too many unmarked doors. Mandagon, in being inspired by Tibetan Buddhism, does the opposite. There’s a brief introductory scene, just a short vertical climb to familiarize you with the controls, and then you’re given a map, a goal, and what’s in between.

Mandagon’s plot isn’t readily apparent. It’s revealed to you in whispered couplets, hidden out of the way, often far from the keys and totems you need to proceed. Failure to find all of these pieces or finding them out of order fractures the story in a way reminiscent of oral history, or déjà vu: we know the players but don’t understand at the plot, or the other way around. It’s very possible to finish the game without encountering the story at all. This works to Mandagon’s advantage, as the verticality and ambiguity combine to make an experience that, for once, there is no pressure to rush through.

And its state of limbo is key. Quiet music and ambient landscape blend together to push the journey above all else as your character ascends rattling wood elevators, sinks deadweight in water only to be pushed up by a stream, and jumps empty gorges with nothing at the bottom but the chance to try again. There’s no death, no enemies. You can startle little crows, if that suits you. There are houses to enter, and totems to find, and great gold birds that give you the temporary power of flight. Story, memory and other mortal things fall by the wayside. You go up.

Find your way through Mandagon on Steam .

The post Climb a mystical mountain in a game based on Tibetan Buddhism appeared first on Kill Screen.

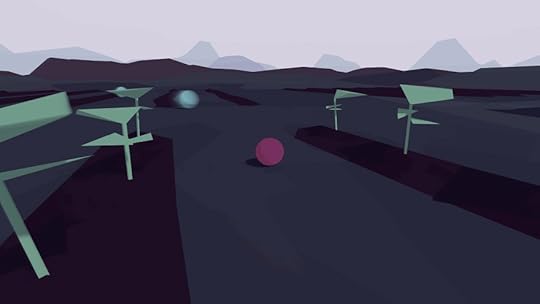

Disc Room distills 1970s dystopias down to a bloody demise

If there’s one thing that Disc Room shares with Vlambeer’s games—the studio for which creator Jan Willem Nijman works under when he’s not toiling away on other projects—it’s the ability to get all the action packed into a single GIF. That and screenshake. Of course it has screenshake.

Disc Room is a game of avoidance—what Nijman calls a “dodge-’em up.” You need to survive 30 seconds in a cramped arena in order to grow old in this spin-off of 70s-inspired dystopian science fiction, including Logan’s Run (1976) and THX 1138 (1971). Your only weapons against the evil discs trying to smear you across the walls are your wit, some reflexes, and the occasional use of slow motion. You better hope it’s enough.

You can see (and hear) the signs of this quality production team

The game’s got impeccable talent behind the scenes, too—that is, other than Nijman. Design duties are shared with Kitty Calis, who’s previously worked with Ragesquid on Action Henk (2015), and she also did the art on the project. There’s also Doseone, co-founder of hip hop label Anticon and musician behind the soundtracks of Gang Beasts and Enter the Gungeon, who is responsible for the sound and music contained in the game. You can see (and hear) the signs of this quality production team every time a disc scythes the player apart.

How Disc Room came to be, however, was a little more higgledy-piggledy. “Humble Bundle asked us earlier this year if we wanted to make a small game for them,” said Nijman, “it seemed like a very refreshing thing to do after both wrapping up huge multi-year projects with Action Henk and Nuclear Throne [2015]. Various ideas were tried and scrapped, and eventually we came to the concept for Disc Room.”

It seems to have been an appropriately scrappy production for a similarly scrappy game. A game in which you’ll unlikely to last longer than 10 seconds as giant buzzsaws and laser balls are shot at you in a tiny arena. If this is to be our future dystopia, at least death will come fast and bloody.

Disc Room is currently available exclusively to subscribers of the Humble Bundle Monthly service. The bundle for August goes out today so if you want it you’ll have to move fast. There’s no word on if it’ll emerge onto other platforms at any time soon.

The post Disc Room distills 1970s dystopias down to a bloody demise appeared first on Kill Screen.

What can architects learn from No Man’s Sky?

Three years after it was initially announced at E3 2013, No Man’s Sky has officially gone gold. Few games in recent memory have created so much buzz. The near-infinite universe that No Man’s Sky offers is plenty reason to be excited but the way Hello Games is creating that universe using procedural generation is equally inspiring.

Procedural generation is a type of design methodology in which components or elements are handcrafted and each given unique properties. These components are then fed into a database which generates forms based on a series of rules and regulations put into place by the designers that dictate what components and elements are used, combined, and generated. Hello Games has created its own periodic table of elements for the universe of No Man’s Sky and assigned properties unique to each element. This allows them to generate 1.8 quintillion planets that are all different from one another and built governing the inherent logic set forth. For example, a certain planet may be in a solar system with two suns, those suns may cause the planet to have an atmosphere composed of a certain gas. That gas may reflect the visible light spectrum different than our own, causing this planet’s sky to be red. The atmosphere would then dictate the planet’s temperature and radiation levels, which in turn affect the flora and fauna that can survive on the planet.

If procedural generation can allow the small team at Hello Games to make what should be the biggest videogame ever in terms of experiential space, what other implications could it have on other design fields? Architecture as a discipline has struggled to manage and understand virtual design. As a result, architectural pedagogy has been undergoing a massive paradigm shift for what has seemed to be the last 40 years. Even now, in 2016, if you attend graduate school at a more traditional East Coast university your introductory studios will revolve around analog architecture, forcing students to sketch and draft by hand. Attend graduate school at a more contemporary university and you can make it through three years of school without ever putting graphite to paper. While computer-aided design software has been around for decades, programs like AutoCAD, SketchUp, and Rhino did not drastically change the nature of architectural design but rather sped it up, made it more efficient, more precise.

The true paradigm shift that occurs in architectural pedagogy comes from the proliferation of parametric design. Parametric modeling has a lot in common with coding and consists of interdependent parts so that one change creates a rippling effect. The two are so similar, in fact, that John May, a faculty member at Harvard Graduate School of Design, believes that coding, not physics and calculus, should be required for all architecture students. In this way, parametric design has a lot in common with procedural generation. In both instances, the designer is not designing form so much as she is designing regulations and constraints that then dictate form. While the two methods share some similarities, they are not the same. The most notable difference comes in their classification, parametric design versus procedural generation.

At its heart, parametric design is still design, it creates one intentional form that adheres to all the fundamental principles of design that have been taught to architects for centuries, only the toolset has changed (albeit, that change requires a new pedagogical approach). A script is designed and it in turn creates a form, but that script is always in service to a particular form. Procedural generation on the other hand functions quite differently. Forms are not designed, they are generated, meaning that there is no longer a strict intentionality behind form nor is there one specific creation. The script and constraints are designed, but they are designed to serve themselves, not the final form. Procedural generation relies on a series of inputs that are capable of generating multiple outputs.

A former classmate of mine, Iman Ansari, who is founding principal of the firm AN.ONYMOUS, lecturer at the USC School of Architecture, and a PhD candidate at UCLA School of Architecture and Urban Design, is able to talk about the implications of No Man’s Sky and procedural generation on the field of architecture. He mentions how architects have always been inspired and influenced by nature and the laws of the natural environment, and how this is slowly beginning to change. “What is exciting about the time we live in now,” Asari said, “is that, beyond the availability of all kinds of alternative or artificial materials and fabrication techniques, we are also able to rethink and reconfigure the rules and conditions that enable and inform them in the first place.” In other words, architects are no longer beholden to conventional rules meant to maintain a natural order. “It is no longer about designing a final object or a product, but about designing or configuring the system or the process of their formation—the underlying code, algorithm, or procedure that can generate not just one but multiple outcomes.”

no longer beholden to conventional rules meant to maintain a natural order

While Hello Games may have designed certain elements (leaves, ears, tails, horns) the true design came in the properties assigned to those elements and the ways in which they work in tandem with all other components of the game. Yet, as Ansari points out, this isn’t drastically different from traditional architectural design. “Design is a dirty word in architecture. Typically, the word implies an arbitrary move or decision-making process primarily concerned with form-making. In my view, ‘design’ is the outcome of a process or procedure, generated from a set of predefined rules and operations—whether defined by the architect, the city, the site, the program, or other factors.” Traditional notions of design have changed according to Ansari. What had been considered a harmonizing mathematical process in the Renaissance and Early Modern Era became an algorithmic process in the last 40 years. As a result, choices and rules set out at the beginning impact every subsequent choice.

Often, the most difficult design projects in architecture schools are the ones that give the fewest restrictions. Architecture is not meant to be free from constraints, it is meant to adapt to them, reason with them, and respond to them. Ansari notes that videogame design will always be unique because it is liberated from many of the rules and restrictions that the physical world relies on. With games, there are no pre-existing conditions, no real world context, and no site, they belong in the realm of the imaginary. The creative process relies just as much on self-imposed constraints as it does on real-world constraints. In many ways, designing a videogame can be more difficult than designing a building because game designers are only left with their own self-imposed rules. This same reason is why it can also be much more appealing to designers. Videogames can produce environments and buildings that are impossible to conceive in the real world.

While the tools that videogame designers and architects use have begun to overlap, the use of those tools will never be quite the same because of the inherent nature of the physical world architects must respond to. “Despite all the possibilities that digital tools provide, the architect always has to scale, trim, or orient the object to accommodate and situate it in within the real physical realm,” said Ansari. “This is something that architecture—or at least built architecture—can never fully renounce. In other words, for architects, there is always a given: a physical, material, legal, and functional environment that architecture has to respond to.”

Sunset in the City of Arts and Sciences, Valencia, Spain by O Palsson

But what would happen if, one day, procedural generation could respond to pre-existing environments? What if one day Mr. and Mrs. Smith could pull up a website, enter a few restrictions and regulations (square footage, climate, lighting, dead load), and out pop 20-30 different homes that all fit their desired constraints? The truth of the matter is that this is a reality which really isn’t that far off. The idea of a Do-It-Yourself home has been around for decades. Domestic architectural catalogs allowed people to pick and choose suburban home designs for communities like Levittown, Pennsylvania. Today, sites like floorplanner.com and plygem.com allow users to design spaces without the help of an architect. I asked Ansari if he thought procedural generation had the potential to be a part of architectural design. “The ‘design’ phase of any project is really about five to 10 percent of the whole work of an architect,” he said. “The rest includes research, development, documentation, representation, engineering, fabrication and all kinds of different tasks that fall outside what we would consider to be the design process.” These extra tasks are time-consuming and make up the bulk of any project. Ansari seemed less interested in procedural generation’s role in design and more in its ability to automate many of these tasks that architects are less inclined to want to do.

He is right, even in school when details and logistics are less important, the most “fun” part of any project is the formulation of the idea: the creative theorizing that leads to the final concept. That is what architects want to do, conceptualize, theorize, and rationalize form, and leave the rest of the stuff up to the engineers and contractors. Very few architects enjoy the process of figuring out exactly how a wall meets the floor, or what the proper window thickness should be. Even fewer enjoy the process of finding those windows in real life. If procedural generation could automate these tasks, architects could focus more of their time and energy on the creative process.

Architecture is more than just walls, doors, and windows

No matter how many rules are set in place or how many regulating constraints are used, procedural generation always implies a certain level of randomness. This randomness can be mitigated to a certain extent but the truth of the matter—in fact the very point of procedural generation—is that the result will be unpredictable. In a universe with 1.8 quintillion planets, a certain degree of randomness and unpredictability is a good thing, it is necessary. But in a singular building? Well, that would be a bad idea according to Ansari. “Randomness is a relatively contemporary concept in design and architects use it a lot in designing facades, floor or ceiling patterns, or other parts of buildings,” he said. “But to use randomness for the building itself is a whole different story.” Buildings always have a clear logic—a programmatic logic, a circulation logic, a structural logic, an environmental logic, a material logic. Randomness can never fully serve as an organizing principle in architecture. “To use language as an analogy here, you can arrange words randomly on a page but they will almost never produce or generate meaning,” Ansari added. “My concern is that if randomness is taken as a design approach in architecture it would produce the same result: it would generate a lot of objects, or at best even buildings, but no meaning, and therefore, no architecture.” Architecture is more than just walls, doors, and windows, just as a novel is more than words. Not only must all the disparate elements come together in a cohesive manner but they must also be produced with purpose and intention. “Maybe one day, computer software would be able to overcome this and produce meaningful forms,” Ansari said. “But at that point, I assume, they would also be able to compose music, write poetry, make films and do everything else. It is not going to be just the architects they would replace. We would all be out of jobs.”

Just as a building must relate and respond to its site, so must it too respond and relate to itself. There is a difference between a building and architecture. It’s one of those “all architecture are buildings but not all buildings are architecture” kinda things. Architects often use the term “Architecture with a capital A” to differentiate between a building and architecture. Architecture has meaning and that meaning often comes from a human element, an intentionality, a sense of purpose, and most importantly an authorship that is necessary in all forms of art. A computer can write a novel, but is it any more than a string of coherent words positioned on a page? Even if, someday, computers are able to compose better songs, write better books, and design better buildings, would we want them to? Art is all about authorship. Computers may one day be able to imitate consciousness or even meaning, but as long as they do not actually have consciousness, their work will always be devoid of intent and true authorship, for that is something unique to the human mind.

When I asked Ansari if he thought we’d ever see the day when architects could be replaced with software he echoed a sentiment that I feel deeply as well. “To be honest I don’t want to live in a world without architects,” he said. And why would he? For a world without architects is a world without painters, musicians, filmmakers, sculptors, and poets. That is a world I hope to never see.

The post What can architects learn from No Man’s Sky? appeared first on Kill Screen.

August 4, 2016

Miyamori will be a foxy love letter to Japanese folklore

Japanese folklore is a pretty common inspiration when it comes to storytelling in videogames. From Clover Studio’s Ōkami (2006) to ZUN’s iconic Touhou Project, Japan’s mythological spirits and creatures provide a familiar backdrop for Japanese game makers to tell their own, new stories to their audience through the cultural legacy of Japan’s mythology.

But the upcoming action-adventure title Miyamori isn’t being made in Japan. Instead, the game features a production crew located across the Western world. Developed by Joshua Hurd, with pixel art from Lachlan Cartland, and promotional art by Kevin Hong, the game features a “folktale-inspired story about community, love, and loss” through Japan’s familiar mythical creatures.

The world draws directly from folklore found in Tōhoku

Miyamori takes place in the Tōhoku region of Honshu, located right in the Japanese countryside. When a young woman named Suzume finds her brother missing, she runs into a shrine guardian fox named Izuna. Izuna, as it turns out, is also looking for her missing shrine guardian partner: a fox named Gedo. Realizing their shared problem, the two proceed to team up with each other in order to figure out the mystery behind the sudden disappearances.

Miyamori‘s love for Japanese folklore can certainly be felt throughout its story and artwork. The world draws directly from folklore found in Tōhoku, with Hurd using such resources as The Book of Yōkai (2015) to carry out the game’s research. Not to mention, Miyamori relies on the traditional Shinto shrine as a cornerstone of the plot, with Izuna and Gedo taking on guardian roles for their shrine as kitsunes. Miyamori isn’t just interested in Japanese folklore; it embraces Japanese culture, and looks to honor and respect the people to which the game’s setting takes place.

Miyamori is planned for a Windows and potential Mac release, and the final version will be localized into Japanese. Players interested in following the game’s development can sign up for Miyamori‘s monthly newsletter through the game’s official website.

The post Miyamori will be a foxy love letter to Japanese folklore appeared first on Kill Screen.

Card Thief’s abstraction of stealth gets more impressive

The last time we saw Card Thief, its creators were in the midst of building a stealth-based approach to card games that has more in common with Thief (1998) than, well, cards. Long story short, Card Thief uses the statistics typical of both card and tabletop games to simulate the effects of light, the direction of vision, and the player’s stealth level. It’s the same thing that might be taken into consideration as you creep behind people’s backs in an RPG, but boiled down to its most simple. It’s the same fundamental change in conditions as crouching down behind a box, just requiring a bit more imagination.

In an update posted to their blog, Tinytouchtales, the developers of Card Thief, have detailed how they experimented with the shadow mechanic so that the player would have a more complex interaction with the beginning and end of turns. They decided to allow players to move through shadows freely, providing more opportunity for play and new interactions with guard characters as well as the ability to move position without removing a card.

[image error]

Since Card Thief maps cards on a sort of grid in order to determine which factors affect which card, the choice to move silently through shadows also affects enemy positions, which, as pointed out in the blog, can be used both defensively and offensively. It adds a tactical edge to the game that was naturally limited when all cards had to be removed after use; suddenly, the weakness of having 0 stealth—a requirement for moving the card in this way—becomes an advantage, as the card is suddenly capable of multiple turns of movement.

Tinytouchtales summed up their blog post by emphasizing the importance of balancing these mechanics: “As always if you add one new thing to your game make sure it solves at least two problems and maybe open [sic] new ways to interact with your core system.”

Card Thief has been a work in progress for a while now, but the developer updates and brief teasers are getting consistently more impressive. With any luck we’ll hear about finishing touches and release dates in the near future, so that we can be just as clumsy in a card game as we are in real life.

Read the full blog post at Card Thief’s website.

The post Card Thief’s abstraction of stealth gets more impressive appeared first on Kill Screen.

Social Gaming: Making Minecraft a game for everyone

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Defying the stereotype that paints gaming as an isolating hobby, Minecrafters use the virtual world as a means of connecting with family and friends in real life. Minecraft (2009) has redefined social gaming for nearly a decade, driven mostly by prolific online communities of creative people. A growing population of Minecrafters is harnessing the power of portable computer technology to interconnect in new ways, bringing their creativity in the digital world into reality.

Aside from a thriving community of modders who build upon each other’s work to achieve incredible feats, a huge number of Let’s Players are making Minecraft the most popular game-related videos on YouTube. Videos of gameplay modifications and how-to tips inspire others to create and share their own videos. This virtuous cycle has attracted more than four billion views in the month of May alone, more than three times that of the second place contender, Grand Theft Auto, according to a report by software company Octoly and gaming research firm Newzoo.

Minecraft in the Real World

Typically played individually using personal computers, Minecraft is moving into living rooms and social gatherings with the help of laptops and the tiny Intel Compute Stick, a full PC the size of a pack of gum that allows people to play Minecraft on any large displays and big TVs with an HDMI port. These portable technologies can turn almost any place into a Minecraft social gaming and collaboration zone.

Technology is also allowing Minecrafters to take their play and interaction into real-world places like clubs, public art exhibits, and festivals. At Mojang’s annual Minecon conference in Southern California, 12,000 Minecrafters come together under one roof to share and create together in person, collaborating on everything from costumes to live builds. Last year, Adam Clarke—a.k.a. Wizard Keen, whose Papercraft video launched him into Minecraft YouTube stardom—curated Make It!, a Minecraft exhibit that showed how virtual creativity in Minecraft influences thinking in the real world. His exhibit celebrated how Minecraft can enrich many aspects of people’s lives. “Social gaming is wonderful because it connects people and brings us closer—no matter where in the world we live,” he explained. “This kind of connection can be a positive force for change in a world where we often feel isolated and alone—play and games do bring people together.”

Public Libraries across the country feature programs dedicated to social playing with Minecraft. The New York Public Library is the meeting place for a Minecraft Club. Super League Gaming is even digitalizing the classic little league experience for kids, hosting events that allow attendees to play Minecraft together on a giant movie theater screen.

By bringing their laptops and connecting to the Super League server in the theater, Minecrafters can simultaneously play in the same physical and virtual space together. As they collaborate on a variety of games and projects through their individual laptops, a bird’s eye view of the server’s world is projected onto the theater’s enormous display screen. Kids get excited about having their creations appear on a huge screen, but they are also intent on watching creations of other players in the audience, according to Brett Morris, president and COO of Super League. “That’s the a-ha moment for them: seeing that Minecraft community in real time, in real life.” The success of Super League shows just how radically social Minecraft has become, Morris continued. “The stereotype is that gamers are somewhat introverted and would rather just play by themselves—but really it’s the exact opposite.”

Minecraft allows players to build off the imagination of the broader community, according to Alex Leavitt PhD, a researcher at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. “There is immense value in social gaming, not only to create new experiences but also for bettering humanity,” Leavitt said. “It will be fascinating to see how games develop in the next five to 10 years and how this affects human behavior.”

The post Social Gaming: Making Minecraft a game for everyone appeared first on Kill Screen.

Killbox, a videogame about the true horror of drone warfare

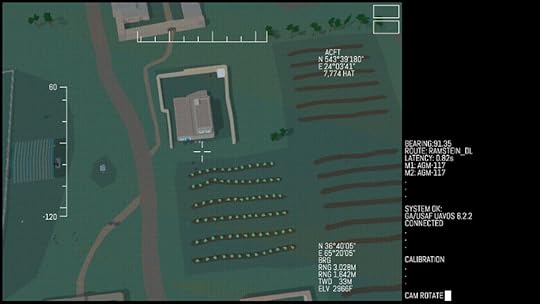

Killbox is a game about drone warfare; about the experience of killing, of dying, and of the yawning expanse between the people doing those two things. It’s also a collaboration between US-based activist Joseph DeLappe and Scotland-based game designers Malath Abbas, Tom Demajo and Albert Elwin—one they hope will leave its mark on the people who encounter it.

“At IndieCade we had a number of players cry once they realized the consequences of the in-game actions,” Abbas explained to me. Having played it I can see why. Killbox tries to get under your skin immediately, before you have time to put your emotional defenses up, before you have time to distance yourself from the subject like so many of us have. At first, the breezy controls of a pastel-colored sandbox caught me off guard, unraveling my cynicism. Later the chilling casualness of fragmented comms chatter filled me with dread, eventually breaking my heart.

“truly a discomfiting experience”

Drone warfare is built on a series of sinister contradictions. The actual aircraft is unmanned, even as the number of people needed on the ground to support automated warfare swells. It’s most effective only on the weakest targets, requiring massive asymmetries in the military capabilities between those involved. And despite the people involved being thousands of miles apart, their interactions distorted and obscured by layers of technology, the drone strike itself is insidiously personal.

“The more research we carried out the more duality would come up as a key thread for me personally,” said Abbas. “I am fascinated by the human-to-human connection created through the physical and digital technology utilized in a drone strike: As a pilot presses the trigger this sends a physical signal that traverses the globe digitally and ultimately launches a chunk of explosive metal and technology that makes direct physical contact with another human being on the ground with devastating consequence.”

This led the team to focus on a multiplayer mode with one player hopping around a carefree, abstract space on the ground, and another analyzing data from above through a drone’s camera feed. As a result, the two come at these dualities from both ends, potentially recovering something from the wreckage in the middle. “From my perspective,” said DeLappe, “the hope is to create a visceral experience that utilizes the attractive nature of a game-based project to draw participants into what is truly a discomfiting experience.”

Killbox’s sound design is crucial to shaping how each player interacts with the game differently. The pilot has absolute power but no freedom, and the villager has absolute freedom, but no power. “The pilot is watching and listening through a technologically mediated experience and the villager is right there,” explained DeMajo. “We wanted the pilot to feel constrained and alert, and the villager to feel free and relaxed.”

The two experiences are connected by what DeMajo calls “parallel sonic threads,” however. “The ambient base for the pilot is a close and persistent machine hum, irregularly punctuated by distorted chatter and occasional machine beeps. From the villager’s perspective, there is the distant and unsettling sound of the drone itself, but this is punctuated by the birdsong and playful interactions.”

In “Phenomenology of a Drone Strike,” Nasser Hussain writes, “In the case of the drone strike footage, the lack of synchronic sound renders it a ghostly world in which the figures seem unalive, even before they are killed. The gaze hovers above in silence.” For the observer below, this relationship is inverted. “If drone operators can see but not hear the world below them, the exact opposite is true for people on the ground.” For residents of the areas targeted in Pakistan, the “low-grade, perpetual buzzing” has become synonymous with death from above, with the psychological terror that results well documented. Drones are “Mostly invisible to the people below them,” notes Hussain, “But they can be heard.”

In many ways, this is the relationship Killbox is trying to capture, one which grows out of encounters based around incompletes. “Killbox’s most dramatic juxtaposition, as far as sound is concerned, is the experience of the strike itself. The pilot hears nothing but sees everything,” said DeMajo. “For the villager on the ground, this is the loudest and scariest moment of their experience.”

“getting people to answer was really the important thing”

What makes these contrasts so stark, however, also makes them tragically complimentary. “The pilot is inside a monophonic and monotonic soundstage that feels one dimensional and inescapable, whereas the villager is in a deep and expansive 360-degree sound space, offering freedom and encouraging exploration,” explained DeMajo. “For the pilot, the continuous and distorted voices make the player feel unable to claim their own personal space—the pilot is a voyeur visually, but in the sound domain it feels like they are being monitored themselves. The villager on the other hand is surrounded by natural and unthreatening sounds, and friendly noises are created by the player themselves as they interact with other characters.”

Killbox is a political project as much as an interactive installation, but whatever questions it asks, whatever activism it invites, are abstruse and free of righteous monologuing. Instead, it’s enough that the game, in Abbas’ words, “crosses and connects physical, cultural and virtual spaces.”

It’s an approach similar to the one taken by Paolo Pedercini and Jim Munroe for Unmanned, a 2012 project about a day in the life of a drone pilot. Players choose how to respond to their environment by crafting the thoughts in the protagonist’s head. “When we were making it the lack of gameplay consequences bothered me a bit,” said Munroe, “but after watching people hover over these choices and really consider them made me realize that just asking the question and getting people to answer was really the important thing.”

By adding a little bit of interactivity and coming at the question of drone warfare sideways, Unmanned proved engaging beyond the surface provocation of its conceit. “When an issue is already out there and extensively debated, artists and cultural producers should think about what they can bring to the table,” Pedercini added. “Way too many socially-engaged artists just ‘put a drone on it’, to paraphrase Portlandia, using the drone as an iconic, evocative, troubling readymade.”

Find out more about Killbox on its website.

The post Killbox, a videogame about the true horror of drone warfare appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Station brings urban legends to life with cute pixel art

One of my favorite urban legends as a child centered on the sewers of New York City. As the story goes, it suddenly became popular in New York to have an alligator as a pet. The giant lizards were kept in fish tanks and then in bathtubs, until owners were horrified to discover that an alligator outgrows even a bathtub, at which point some great number of alligators were sneaked to the sewers, where they now live.

the unknown realms behind storm drains

As the world gradually demonstrates that monsters and wizards are much harder to come by than you expected as a child, there are spaces that still hold onto some mystery and magic. That promise of strange worlds underneath our everyday lives is what drives The Station, a French game from Pixel-Boy. In the demo, which also functions as a tutorial, the player starts her first day of work in the sewers with a test from a cheerful boss. The pests she’s tasked with dealing with are “foggies,” who essentially appear to be dirt and grime come to life.

The player is not without help—she’s armed with a “capture wand” and one of three friendly “creatures” who spits projectiles made of fire, water, or grass. The reference is obvious and loving. Pokémon, too, took place in spaces—cities and small towns—that were fictional, but familiar to young players. They resembled the real world, only full of dragons and adorable magical creatures.

The accompanying creatures level up, and change as they do, with a weapon system that feels a lot like Cave Story (2004), another game that looks to the past with admiration. The characters, too, would fit in that game, given their immediate charm and precise pixel art. There’s even a cute loudmouth mini-boss. There’s something fantastical about the unknown realms behind storm drains and further down the subway tunnel, and The Station is posed to tell stories about them.

You can download The Station over on itch.io.

The post The Station brings urban legends to life with cute pixel art appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers