Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 83

July 29, 2016

Play with words in a videogame about weird idioms

English is a curious language. It’s deceptively easy to pick up, oversimplified and left bare by our lack of gendered nouns and relatively easy cases, but as anyone with a different mother tongue will tell you, mastering it is incredibly hard. It’s a carefree language that pays little heed to convention or regulation, preferring to wander and expound and run-on and twist itself in knots, all while remaining within the bounds of “correct” grammatical structure. We constantly ignore our standard sounds while stealing words from other languages and mangling theirs, too. And if that wasn’t enough, if the transgressions made by the English language against common sense were somehow lacking, we have some wild idioms. As do many languages, of course, and once integrated into regular speech they become conventional, but for some reason we talk about cats all the time.

in celebration of the bizarre, senseless English language

In celebration of the bizarre, senseless English language, designer Tim Garbos and animator Veronica Jelinek have created It Ain’t Over Till The Fat Lady Sings, an interactive animation currently up on itch.io. With bright pinks and blues, Fat Lady translates all our little idiosyncrasies quite literally, whether it be extending an umbrella to fend away the rain of cats and dogs or rolling the credits with the titular character’s loud opera in the background.

Sound effects reinforce the chunky animation—“catch her eye” contains some disconcerting squelching—and the whole thing has a wonderfully complete feel to it. The experience is only a few minutes long, illustrating six different idioms with simple mechanics, but games are ripe for this kind of bold aesthetic: Jenny Jiao Hsia’s Wobble Yoga and Morning Makeup Madness are two such instances. You could easily see this as a longer game, or perhaps an animated film.

Fat Lady is a clever mix of wordplay with real play, and a wonderful experiment with what games can do. Many people focus so strongly on vast gameplay and narrative that the act of singular, simple interaction goes unnoticed. If “walking simulators” have to defend their game-hood than the act of clicking a cloud inside a teacup is surely also an offense; but if we expand our definition to include pieces of art with limited interactivity, games get a whole lot more interesting. Fat Lady takes a simple premise—English is weird, and that’s funny—and brings it to life. No flourishes necessary.

Play It Ain’t Over Till The Fat Lady Sings on itch.io.

The post Play with words in a videogame about weird idioms appeared first on Kill Screen.

The fierce independence of the No Man’s Sky soundtrack

Samizdat—literally “I self publish” in its native Russian—is a term that buzzes with connective meaning. First used by the poet Nikolai Glazkov, it describes the banned political essays, literature, music, and poetry that were circulated by makeshift independent presses in the Eastern Bloc. A response to the extreme censorship of foreign and dissident works during the 1950s and 60s, samizdat publications were emblematic of a fierce spirit of independence, produced through unlikely means. Carbon-copied verse, hand-typed novels, even bone records cut from old X-rays, were distributed by hand, passed from trusted friend to trusted friend, to be read or listened to in the deepest parts of the night, under a flickering candle.

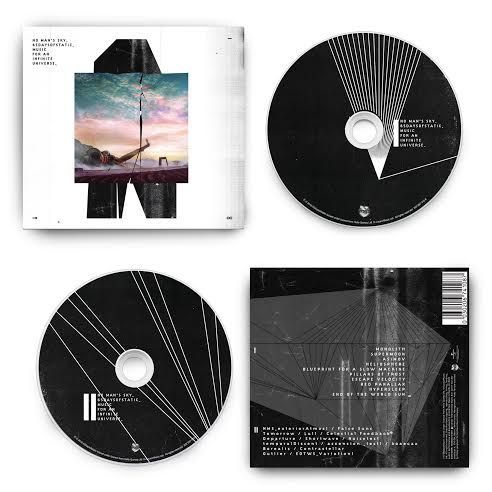

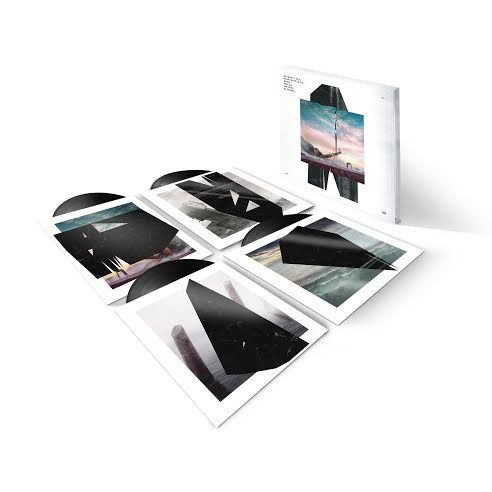

So when the word comes up in my conversation with designer Caspar Newbolt about his work on 65daysofstatic’s soundtrack for No Man’s Sky my ears prick up. Newbolt, director of Version Industries, is responsible for the idiosyncratic art that adorns 65daysofstatic’s new release, but to call him a cover designer would be a great disservice. He is one of the collaborators that make up 65’s wider creative circle, and his work with them has been a decade-long relationship of thoughtful design. “I was talking with the band a few days ago,” Newbolt explains, “and one of them used a word that I think really encapsulated everything that we’d done here together. That word was samizdat.”

music for an infinite universe

Newbolt is a hard man to pin down. When I ask him about the sigils that mark the cover of the album design, or the fractured main image he dodges the question: “It’s always my interest to not explain a great deal,” he says, before politely adding “so that the work can speak for itself as much as possible.” His reasoning is sound: “we’ve had a lot of questions already about what it all means, and like a good record or film I think there’s a greater value in people forming their own interpretations.” But he does, after a little pushing, give me a thread to follow, that word— samizdat. And it’s a good thread, one that sets my mind running when I look at the art that surrounds the album.

It’s there in the cover’s heavy wear; a texture that might have flowered from a photocopier or scanner—digital and analog decay creeping in at the edges. Then there’s the central painting, by collaborator John DeLucca, which is split like a photographic plate, or perhaps just cut with a photoshop marquee, the clean breaks betraying neither one origin nor the other. A monolith of sorts sits behind, peppered with more copier noise, its sharp angles part alien sigil, part choppy-scissor cut-out. In short, it looks like an elegant bootleg, an artifact of digital and practical processes of distribution, rich with error and obscurity. This theme is carried across its iterations, in the branching diagrams that adorn the CD, and the four chopped and blocked landscapes that lie inside the chunky four LP boxset.

For Newbolt, this aggressive treatment emerged from navigating the disparate styles that defined both No Man’s Sky’s saturated dreamscapes and 65daysofstatic’s black-market chic: “No Man’s Sky, the game, is clearly a tremendously well executed project with a strong, pre-established aesthetic.” He explains that “the game’s soundtrack was similarly composed and structured in the way few have ever been before. Faced with these facts I had to conceive a visual that somehow spoke to these different concerns, and that helped you see and hear the music through 65’s own eyes and ears.” The result was the obscure, ambiguous design you see now, one that splits from the game’s clean lines by muddying them with layers of noise. For Newbolt, this was not just about style, but legacy. “What you see in the artwork is the No Man’s Sky aesthetic filtered through 10 years of knowing a band who, like the game’s procedural score, never stop trying to find new ways to express themselves.”

But what of the soundtrack itself, how does it navigate the disparate styles and demands of No Man’s Sky and 65daysofstatic’s differing identities? The first track, “Monolith” is a good indication. Drifting in on building layers of guitar drones before locking into a clipped drum beat, it feels instantly recognizable as part of 65’s own style. Yet, before long, that conventional intro decays into a urgent synth line, which leads us willingly into the face of some glorious, reverb-rich fuzz. Everything is gathered, layered, stretched, crushed, and by the time groaning errors light up the dark drumbeats like glitched suns, it’s hard to feel you are listening to the same track. It’s decay at high velocity, built on repeating structures that fall and build in a linear form designed to transition you from one state to another. This journey from signal to noise and back again is what animates the album.

Each of the other tracks in this collection possess their own territory on this spectrum. “Supermoon” (perhaps the most recognizable, having been used in No Man’s Sky’s trailers) sits at one end; the 65 signature drum-beat a guideline through lilting layers of bright-eyed piano and spaced-out choirs. It feels like comfortable place for 65, a building set of rifts that push for euphoric release, sprinkled with those blippy synths they handle so well. “Asimov” seems like it might occupy the same space until a mid-song lull lays the ground for the closest the album gets to an almighty drop, one that through hammer-blow drumbeats and some rare unadorned strumming feels like the most post-rock this band will ever get.

“Heliosphere” and the perfectly named “Blueprint for a Slow Machine” reroute the path, wiring us directly into a Proteus-like world of twinkling digital flora and fauna, albeit with an ever-present bedrock of dark drones. This is true science-fiction territory, with “Slow Machine” even launching itself as a Vangelis tribute act before suddenly churning into an interlocking structure of drum machines and dysfunctional electronica. Yet both refuse to reach the end of their five minutes without those crowd pleasing guitar riffs and beat-perfect drum rhythms sneaking in and brashly taking over the show. As though to provide a counter argument to that point, the following track, “Pillars of Frost,” marks our arrival the other end of that signal to noise spectrum: a washed out and frankly beautiful wall of distortion. Here is the split plate, the sharp edges, the flowering grain across a distant landscape. The empty and yet full air of another earth.

Having stranded us on that shore of noise, the album senses that it is time to bring us home again. The piano returns in “Escape Velocity,” laying down a scale of footfalls to guide us to whatever craft will bear us back. It is built of the familiar; “Red Parallax,” the shimmering new; “Hypersleep,” and the ornate mechanisms present in the uplifting form of “End of the World Sun”. From this far end, it is easy to see it as a journey in both one and many parts, its total structure possessing a distinct shape that is mirrored and distorted in each of its pieces. 65’s strength has always been in their synchonizationation of the analog and digital, shaping seemingly contrasting sounds into coherent landscapes. As an album, No Man’s Sky: Music for an Infinite Universe feels like a powerful actualization of this process.

And we should call it by its full name, because 65 deserves recognition for producing an album with its own independent spirit rather than just a soundtrack. Perhaps it is because they have pushed the ambient, procedural soundscapes that will accompany much of the game onto a second Soundscapes disk, allowing their 10 tracks the breathing room they need. This second disk, a set of glittering backdrops that wander easily across the tones of the album, dragging out moments to eternities, makes for a strong companion. There is something pleasing about the rudimentary parts of the track titles, such as “NMS_exteriorAtmos1” or “ascenion_test1,” that point not just to the exploratory processes used in their making, but also that bootleg aesthetic that feels central to the album and 65. The grouping of the tracks, their aimlessness and impregnability, play beautifully into the sense that this second disk is a mysterious artifact, the kind you might find on a dusty CD-R, etched with marker pen letters in some impregnable alien language.

This is perhaps the clear point of unity between No Man’s Sky and this album: Not only do they share concerns and ideas, but the same sense mystery and obscurity as well as an obsession with the artifacts of a digital world. Rather than simply mirror each other, or form an obvious hierarchy, this allows these two distinct works to sit side by side.

Listening to the album, and perhaps guided by its layers of building fuzz, I couldn’t help but think of the band HEALTH and their work for Max Payne 3 (2012). One of the all time great soundtracks of any game; inventive, surprising, and beautifully produced (just listen to the track “Shells” if you don’t believe me), I was surprised to find out that it marked a dark period for the band. “When the game came out, most of our fans were just like, ‘When are you guys gonna do anything?’”commented bassist John Famiglietti in an interview with Pitchfork, adding “our fans have been aggressively pissed at us for the last three or four years.” Perhaps this was because, unlike 65, HEALTH’s soundtrack was released as a wandering set of mismatched tracks, gathered with the Emicida track from the game, and plastered with the game’s cover art and an “OFFICIAL SOUNDTRACK” tagline. In short, they gave up their independence, or had it taken from them.

Speaking to Newbolt it’s clear that, at least in part, we have No Man’s Sky developer Hello Games to thank for 65 avoiding this unproductive approach. “Hello Games are big fans of 65daysofstatic.” he explains, “in understanding 65 the way they do, they very much wanted them to approach the soundtrack the way they’d approach any of their own albums.” But it is also clear that the album’s independence didn’t come without a struggle. And in a project as big and with as much potential as No Man’s Sky, it’s not surprising to hear that there were some battles along the way. Newbolt sees that conflict as all part of what the band does: “As a partnership we’ve come to learn over time that our best work doesn’t come without a good fight. We simply have to keep pushing each other to articulate what we really want to say, whether that is to each other or to others.” Who those others were Newbolt doesn’t make clear, but he makes it clear that the focus of both the band and himself have been and always will be firmly on what they want to say, not on how others want them to say it: “Naturally this often comes in spite of what the expectation from outside parties might be, and in this case the expectation was of course very different from any of our previous projects.”

from signal to noise and back again

In a way, it seems that 65, and Newbolt, weathered that particular storm through a sense of aesthetic unity. “I’ve known and worked with the band for 10 years now, and twice have toured with them in different parts of the world,” Newbolt says. “In this time we’ve come to understand and trust each other.” This trust is what allowed Newbolt to produce such distinct work for the album’s cover. “I was given a copy of this soundtrack early on and I knew, as ever, that being responsible for creating visuals for this record would push me to do some of the best work I’d ever done.” In a sense, this idea of trust, but also of collaboration is central to the successes of No Man’s Sky: Music for an Infinite Universe as a total work. The trust of Hello Games instigated the idea of an album to sit alongside the game, not in service of it, and the clear trust between the band members and its collaborators allowed them to follow through on this idea.

That samizdat slogan, “I self publish,” also implies the idea that “I self define.”. With that in mind, we can see how 65daysofstatic’s insistence on their artistic independence, their fierce sense of individuality in their music and their self-knowledge as a creative group of collaborators have led to the creation of a defining work. No matter the success or failures of No Man’s Sky, the band and their collaborators can feel safe in their own independence, and in their desire to pursue their own intentions. It is the alignment of ideas that makes for strong collaboration, not the rule of one single, all-powerful idea. In that way, projects like this become a game of listening, not just to others, but to the directions of the work itself. As Newbolt puts it: “We’re never really out of touch, but it takes a moment to tune back into each other’s frequencies.” This truth suggests that among all that noise, there is signal after all.

The post The fierce independence of the No Man’s Sky soundtrack appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 28, 2016

Orbyss brings the beauty of ribbon gymnastics to your phone

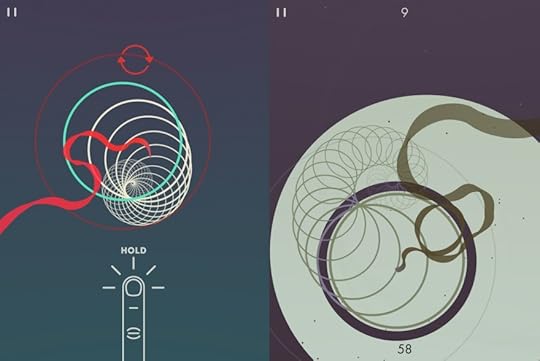

Super Hexagon (2012) has you think in hexagons, Orbyss in circles. Repeat that: Orbyss. Circles. Don’t stop there, either. You should chant this to yourself quietly—or just in your head—as you play Orbyss. You’re gonna need to. Circles, circles, circles. Loops, loops, loops. For if you don’t drill that command into your brain you shall fail. You’ll fail anyway, a lot, like every five seconds, but with a little persistence you can match the complex elegance of a ribbon-twirling rhythmic gymnast.

That’s what Orbyss mimics as you get better at it too—a magical performance of flutters and twirls. It’s a game about whirling ribbons and the repeated act of practice it takes to create beautiful performative art. But you won’t think so at first—a deception similar to Burgess Voshell’s previous game DYG. When you begin it seems as tightly closed as a particularly stubborn orange peel. You tap the screen to send a ribbon accelerating towards a 3D tunnel that looks like it was drawn with a Spirograph set. During its approach, another instruction pops up on the screen telling you to hold your finger down. You do so and the ribbon starts circling anti-clockwise. Lift it and it will resume its travel clockwise.

a tangled distortion of chaos

I’ve told you that like it’s obvious but it’s anything but. The reason being that Orbyss barely gives you a chance to work out what the heck to do before you collide with an invisible wall and fail. An integrated Twitter prompt appears upon your crash as if to mock you: “Still learning,” it says. “I love a good brutal challenge,” is another. Why would you let your Twitter followers know of such a failure? You wouldn’t. Later on, however, with a better grasp of the game, this call to Twitter turns into a celebration of your resolve—that’s when you might be tempted to share the game’s automated words, a sign of victory.

Before then, these few words that arrive upon your failure serve to keep you curious. What are you still learning? There are no further instructions so you have to micro-analyze what your touch on the screen is doing, parsing the difficulty of locomotion in this wiggling foreign body. It really does feel as piecemeal as taking tiny chunks of peel off an orange; desperate for a whole curl (of understanding) to follow your fingers. Once you’ve worked out how to steer the ribbon you then have to get a feel for it. This will take a lot longer. The goal is to guide the ribbon through the serpentine tunnel, able only to do so in arcs, half circles, and noodly paths. It can quickly become a tangled distortion of chaos.

But perhaps this is a small price to pay. Gymnasts train from a young age, fitting in seven hours of training in a day, three days per week, while at school age. Not to mention the strict diets they have to adhere to, and the almost-criminal muscle stretches they are put through to ensure their body remains limber and supple. All you have to do while playing Orbyss is spend a few minutes of your day tapping a screen while you’ve nothing else to do. You’re not going to compete at the Olympics, but you might put on a pretty little show for yourself as you loop the ribbon through five, 10, 20 circles and more in its winding abyssal tunnel.

You can purchase Orbyss for $1.99 on iPhone and iPad.

The post Orbyss brings the beauty of ribbon gymnastics to your phone appeared first on Kill Screen.

GLITCHED will break the fourth wall just to be your friend

You’ve lived in the same town all your life, a tiny idyllic village well removed from the world beyond its borders. Life is simple but reassuring in the way of a well-maintained schedule or a checked-off to-do list, and you have very little to want or desire beyond it. You’re content to tread well-worn paths with your best friend and ask nothing else of life. One day, in flagrant defiance of all established patterns, your friend says that he’s going away—reasons unknown, motive mysterious. The night before his departure he disappears, and you look up at the sky, and see Something. This is the premise of GLITCHED.

Your name is Gus, as it turns out. You’re about 20-pixels high, brown hair, green shirt, cute walking animation. Your friend’s name is Conrad, and he’s been glitched out of existence. The person up in the sky is you—real you, sitting on the subway staring a little too close at your phone screen you. This is GLITCHED’s gimmick: the fourth wall? It’s gone. Far, far away. Gus, the friendly avatar, is going to spend the game interacting with you.

the fourth wall is gone

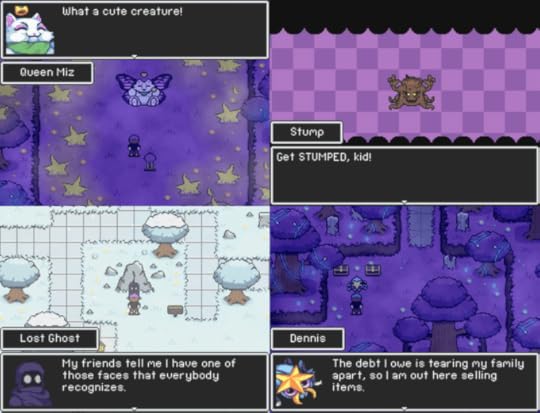

Besides this quirk, GLITCHED has a pretty standard agenda: explore the world, meet new characters, maybe fight some stuff, maybe catch a Pokémon discover a small animal. Personality is tracked through the “Essence System,” which means all actions influence the development of one of six alignments: zeal, insight, harmony, conquest, drift, and bastion. Instead of being a karma system like Fallout 3 (2008) or mappable alignments like Dungeons & Dragons (1974), it emphasizes traits or ideologies that are supported by the choices you and Gus make, both in dialogue and in the larger game. Arya Stark’s going to end up with high zeal, while Sansa might end up with insight or harmony.

GLITCHED also rejects the tall-grass combat system of getting ambushed out of nowhere by Zigzagoons, preferring to keep combat within the story. All combat is triggered through dialogue, and many times you can talk characters down, flee, or otherwise avoid getting physical. You’ll have party members and shiny equipment to shake things up, and most battles will have variable endings: you can talk to enemies instead of killing them. Like Undertale (2015), the game often rewards getting creative instead of taking the easy way through.

For those of you that can’t wait to get started, GLITCHED has a demo to go along with its Kickstarter campaign (which has already surpassed the funding goal) and, as promised, the fourth wall is smashed to bits within seconds of opening it. Stretch goals that have already been unlocked include a customizable town, a collectable “Bebo” farm (bird-ostrich-things?), and an arcade combat minigame, with new quests, more characters, and New Game+ still to come. Whenever you choose to enter this world, Gus’ll be waiting for you.

Support GLITCHED on Kickstarter , and play their demo .

The post GLITCHED will break the fourth wall just to be your friend appeared first on Kill Screen.

Chat with lonely ghosts in Indigo Child

In the 80s and 90s, “indigo children” were a topic out of New Age philosophy that gained some mainstream popularity. The idea was that certain gifted children might possess unusual or paranormal abilities. It’s the kind of thing that would have made for a good X-Files episode, or if you’re developer Metkis, it makes for a good short game.

Indigo Child is about talking to ghosts, but it has an air of melancholy you won’t find in Wadjet Eye’s Blackwell series, despite the shared premise of a character who can talk to ghosts in order to help them find peace in the afterlife. Where Blackwell games are heavy on dialogue and feature the item-based puzzle design of older adventure games, in Indigo Child, the world is bleak, and communication is minimal.

rhythmic and mournful

Moving feels like walking through syrup. The puzzle isn’t really a traditional puzzle, so much as it is a logical set of interactions you have to figure out. The game does not provide hints or point you toward their solutions, and instead waits for you to stumble onto its logic. In order to bring ghosts from their uneasy resting places to their former owners, you must call them periodically to make sure they’re still following you. It’s rhythmic and mournful, but simple, without much of the investigation of death or its characters as you might expect.

Recently, there’s something of a psychological consensus that the idea of having an “indigo child” appealed especially to parents who didn’t want to consider that their children could have some form of mental health issue. It served as a kind of alternative diagnosis to explain behavior that would isolate children or change how they communicated. In Indigo Child, that isolation is blended with the sadness of three lonely deaths.

Metkis describes it as a “gamejam style experience,” which feels accurate—it’s the sort of small game that introduces an idea and starts to explore how to approach it. Here, the adventure game stylings are merged with a somber subject. The game lasts just long enough to convey a specific feeling, and then sends you on your way.

You can download Indigo Child on itch.io.

The post Chat with lonely ghosts in Indigo Child appeared first on Kill Screen.

The glitch noise and cassette tape nostalgia of Nico Antwerp’s new album

“In the crowd of a subway station, commuters stand on the platform of an impersonal world, in a situation that may well stand as epitome of modern high-tech civilisation.” This is what Nico Antwerp had to say about the inspiration behind “music for jostling commuters,” a 2:32 track set for release later this year on audio cassette.

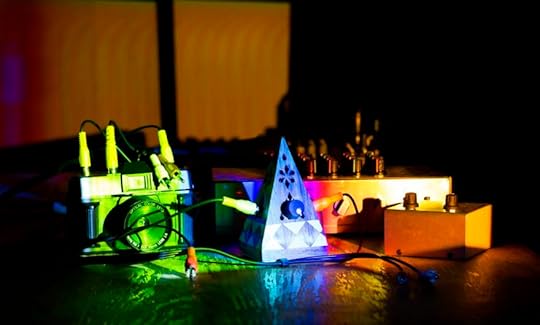

Antwerp is a frequent collaborator with visual artists (see his work on Dreamland) and the collaboration with Benjamin Sammon marries the similarities of their craft. Antwerp’s music carries with it the strains of the -wave and -punk internet subgenres that have come before it, and Sammon’s “glitched out colourscapes” do as well. Combining “analogue video techniques,” including “a mixer built into an incense pyramid” and a “mixer based on the Karl Klomp dirty mixer, which [he] built into the body of an old stills camera,” Sammon fused his unique visual style with Antwerp’s jams.

Cassette has been marked for years as a low fidelity piece of equipment, often derided in the place of the more popular analog: vinyl. With cassette tapes making a comeback, both in popular conceptions of their quality (a cassette is only bad if you are listening to a cheap cassette on a cheap system—go figure) and in terms of nostalgia, it goes especially well with Antwerp’s music:

“Nowadays we can record Lo-Fi sounds but in the end we still produce our tracks on a Mac, so I don’t think we can really talk about low fidelity anymore. We can now play with some sort of contradictions… Cassette tapes, throughout the 90s were essential as you could listen to music while travelling.”

“nostalgic about an evocative tangible design”

Since Antwerp’s music in this case was designed with the traveling commuter in mind, it makes sense that there is this connection to a physical media made popular by the Walkman and the over-the-shoulder boombox—this is the system for the music listener on the go.

There is also something to be said for a piece of media that you can hold in your hand. “I am only nostalgic about an evocative tangible design,” Antwerp writes. With a digital age producing its own separation between consumer and consumed, why not bring back the tangible in creative design?

You can listen to the full album, KELMU, which is a selection of live recordings of Antwerp’s work, when it is released this fall.

The post The glitch noise and cassette tape nostalgia of Nico Antwerp’s new album appeared first on Kill Screen.

Why we’re relaunching our print magazine

Header image by Rune Fisker

///

In less than two weeks, we are relaunching our print magazine with Issue 9. We’re incredibly excited to show you what we’ve been working on. For a limited time, use the discount code RELAUNCH to receive 10% off your purchase of Issue 9, or off a 4 issue subscription.

When we founded Kill Screen only seven years ago, the “game world” was a surprisingly different place. Many of the presumed fault lines in games—between independent and mainstream, artful and commercial, local and global—were just starting to penetrate the public discourse. “Indie Games” had been around since the early 80s, but as an organizing principle, the concept was new and exciting. Facebook games were huge. (Remember FarmVille?) In less than a decade, games culture has exploded, not necessarily growing so much as diversifying and opening up. So many different people play so many different games in so many different ways.

Over this time, Kill Screen as a company has changed, too. Our site has grown exponentially, and we’ve been able to launch esports and VR verticals—with more projects in the works. Still, one aspect of the Kill Screen identity has remained true since the beginning: we don’t want to look at games in a vacuum, siloed off from other parts of our lives. At our core, we are a company focusing on lived experience, on games as part of culture, on games in life.

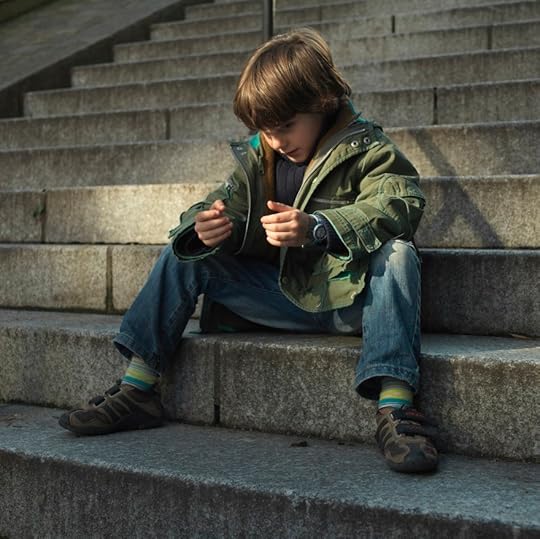

Some of you may remember that Kill Screen started as a print magazine. Issue Zero, “The Maturity Issue” as we dubbed it, featured an image of a boy sitting on a brick stoop, an imaginary controller between his hands. The image supports our essence: games are played out in the world, hunched on brick steps, beneath graffiti art or paintings, with friends, as we eat food, in movie theaters and in playhouses at intermission, walking through parks catching Pokemon. Games intersect with all the other aspects of our lived experiences. Games are part of culture, and not a culture unto themselves.

At our core, we are a company focusing on lived experience, on games as part of culture, on games in life.

Relaunching a print magazine at a time when digital and screened experiences dominate our lives with games may seem ill-fated or foolish, but we believe in the value of an artistic artifact. We love the smell of ink. Beautiful art excites us. We enjoy flipping a book’s pages, just glancing at them as they flap by, choosing a place to start reading. We feel a little pride having something beautiful on our coffee tables, on our shelves, even on the back of our toilets. We thrill at finding something in our mailboxes. The new Kill Screen print magazine is another way to engage games and meaningful discourse about games, but from a distance; not playing, or leaning into the screens, but with a book in our hands.

We believe Kill Screen is at its best in print, and that reading about games in a physical book may actually help us appreciate games more.

Issue 9 will be in your hands soon. None of it would have been possible had it not been for the support and enthusiasm of the Kickstarter backers, who quite literally made this relaunch possible. To those backers: thank you, and your first issue is coming soon. To everyone else who is reading this: you can subscribe today and start with Issue 9. We really hope you all enjoy having it as much as we have enjoyed putting it together!

For a limited time, use the discount code RELAUNCH to receive 10% off your purchase of Issue 9, or off a 4 issue subscription.

The post Why we’re relaunching our print magazine appeared first on Kill Screen.

This Is The Police won’t accept blame

Content Warning: discussion of rape, violence against women, police brutality, racism.

This is the police. This is the police station. This is the police chief. The police chief is you. This is your desk. This is your scanner. It will be your Beatrice, a voice beckoning you to rise from the grime. It is the only voice in the world that begs to be silenced. But you relish it, this song from the streets. It reminds you that you still have a purpose, two-timing wife be damned; it reassures you that you are still the man they come to around here. You take comfort from the fact that it will stop singing only when you’ve stopped being able to hear it.

This is Freeburg. This is your city. You’re the most popular police chief in the history of the city, and the most morally upstanding. Everyone says so. Well, everyone except the feminists. And the black citizens of Freeburg, they also seem upset—but you, the police chief, you know that they just want attention. You always know what people want. That’s how you ended up here. It’s why you’re so good at navigating the press conferences and misconduct hearings; you understand how to redirect blame where it will hurt you least. After all, City Hall is the real problem. You’re just doing your job.

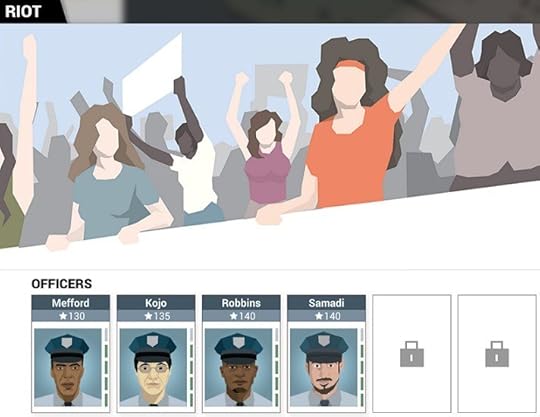

This is your city. This, right here in the middle of your office, is a model of your city. It allows you to see, in a glance, where crimes are called in and what progress your officers have made in responding to them. It’s a real headache sometimes, trying to follow it all. Sometimes you blow off calls out of sheer exhaustion. But other times, when it’s quiet on the streets and the last squad car is pulling in for the night, you like to pop a few painkillers, have a sip of whiskey, and survey your miniature world in the fading lamplight. You like how orderly it all looks from above: the residences sorted neatly into identical rows, the looming skyscrapers reduced to the size of your boot, the ghetto safely cordoned off to the side. The silence and stillness. The peace. For just the briefest of moments, you wonder why the real world can’t be so. Then you pour yourself another drink.

///

The first command you receive in This Is the Police is to fire all the black cops. That’s not a matter of interpretation: the directive actually says “Fire all black cops.” In a game that gives you 180 days to play through, this happens on day four. A justification of sorts is offered. It seems that there are bands of racist gangs on the loose in Freeburg, and they have called City Hall to say that any black people in government positions would become targets. Mayor Rogers, the mindlessly bigoted serial rapist that serves as your primary antagonist in the game, decides that it is easier to just fire all of them. Never mind that the police are the people who might put a stop to the racist gangs; risk assessment is paramount in this game, both for you and the mayor.

This initial, eyebrow-raising episode turns out to be a model for the way the rest of the game will proceed. The majority of your time as chief is spent dispatching your police officers to crime scenes, and following up on the results. But your ability to respond to crimes is contingent on having the resources to do so, and these are allocated by City Hall. So, whenever the mayor has a problem that might be best solved through force, you send out the SWAT team. Or if he needs the department to display a particular skin color to earn political capital, you make it so. It’s true that the game does give you the option to turn down these uniformly heinous directives. But if doing so may assuage your conscience, it also hurts the police force, and thus the citizens of Freeburg. The game’s incentive structure essentially forces you into compliance, hence corruption. But underneath it all, it suggests, you’re just trying to do the right thing.

The Freeburg police force has, in fact, an extraordinarily high turnover rate. One day you’re ordered to fire all the old cops on your staff. On another, the mayor tells you that he wants at least four Asian officers present to impress a visitor, so you need to clear out a few spots. But since the game doesn’t actually tell you the race or age of your employees, you are forced to profile: this person’s name sounds kind of Asian; that person looks sufficiently old. You will be penalized for getting it wrong. In case this sounds like a fun or interesting thing to do in a videogame, I assure you it is not. Yet it is relatively innocuous compared to some of your other duties.

you must explicitly authorize the use of force

Perhaps the definitive episode of the first half of the game centers around a conflict with “the feminists.” The mayor orders you to send in the SWAT team to shut down a feminist protest at City Hall. To complete the mission as assigned, you must explicitly authorize the use of force: “Let’s show them what intimidation looks like, up close and personal.” Like all other citizens in the game, the feminists are voiceless and faceless. (Quite literally: the game illustrates their bodies without faces.) But when you get in trouble for ordering the police assault, and you have the option of framing one of your own for initiating the violence, the game fills in the dialogue for you. “He couldn’t wait to turn their faces into bloody messes,” it says. Whatever gets you off the hook.

///

This Is the Police is the first game created by Weappy, a small studio in Minsk, Belarus. Like many North Americans, I knew almost nothing about Belarus when I started playing the game. I didn’t know that it is commonly referred to as “Europe’s last dictatorship,” or that sitting President Alexander Lukashenko has been in power since 1994, or that his government has a long and well-documented history of violating human rights. Thinking that some of these facts might be relevant to a game ostensibly critiquing law enforcement, I contacted development lead Ilya Yanovich to get some context for a game that badly needs it.

Yanovich never responded to my questions, but a few days later he posted an open letter on Weappy’s website directed at inquisitive journalists. The letter outlines three “caveats” about the game. First, Yanovich claims that his country’s history is irrelevant to an evaluation of the game: “This Is the Police is not about the United States or any other individual country,” including Belarus. “We deliberately did not specify when and where the events in the game unfold—not because we were being cryptic, but because it doesn’t matter.” The designers want to explore universal issues: “The problems of every individual are the problems of all mankind.”

As noble as this principle is, it is hard to endorse in 2016. Freeburg may be a generic Western city, but not all of humankind lives in generic Western cities. I have no idea what a game called This Is the Police would look like if it was made in Singapore or Iran, but I suspect that it would be very different. This game probably wouldn’t be made in Canada either, at least not in its current form—the sheer proliferation of derogatory language and identity-based violence would be unthinkable in today’s climate, and for good reason. Moreover, the orders to shut down peaceful protests with nightsticks and SWAT teams feel genuinely alien from where I’m sitting, because Canada doesn’t have the same laws against public assembly that Belarus does. These kinds of differences should be highlighted by a game this immersed in real-world affairs, not erased in the name of some fictional ur-state.

Along the same lines, Weappy representatives have apparently been inundated with questions about how their game relates to the scourge of police-related violence currently plaguing America. To their credit, the developers have been consistent and forthright on this issue. They condemn the shootings like the rest of the world, but they started the game long before that conversation picked up traction, and their game has nothing to do with it. Which is true: of all the shades of corruption and villainy explored in This Is the Police, you will never have to answer for the police shooting of an unarmed citizen. One could wish this issue was raised somehow, but I don’t think there is anything here to fault the developers for.

Their final claim to self-exoneration, however, is harder to interpret. “This Is the Police is not a political game, but a human one,” says Yanovich. “We do not believe that the problems discussed in the game are political in nature.” He offers a personal explanation:

A couple of times when I’ve been at protests, I’ve seen people peacefully expressing their dissatisfaction, and receiving a club in the face. Of course, the reasons why people took to the streets, and the reasons they were broken up, are directly related to policy. But that terrible moment when a person suddenly decides that he has the right to hit another person, that devastating moment when the thought enters his mind—that has no relation to governments, parties, or laws. It doesn’t matter what country or continent you’re on, your gender, sexual orientation, skin color, or religion. Because it’s not a matter of politics. It is a question of humanity.

There are two possible ways to interpret this. The first is to take it straightforwardly, in which case we have to ask: what is the point? If This Is the Police doesn’t deal with political problems, then why does the player need to spend hours polishing their racial profiling techniques? Why lie our way through the press conferences? How else should we classify the struggle against scarcity and the heavy hand of that notable politician, the mayor? If gender and skin color don’t matter in this game, then why do we spend so much time beating up women and black people? Where is the humanity that Yanovich speaks of?

Weappy may well need to protect themselves from the law

The other, very real possibility is that This Is the Police is a thoroughly political game, but its creators are unable to admit it. Consider: how do you make a game about a corrupt government in Europe’s last dictatorship? You do so by presenting it as a completely apolitical, “human” story with “no relation to governments, parties, or laws.” If Yanovich’s letter reads a bit like a legal document, that’s because Weappy may well need to protect themselves from the law.

I have no evidence that this is actually the case, of course. But it makes sense of the game in a way Yanovich’s actual words don’t. If Yanovich has himself been a protester, and has seen the effects of violence first-hand, it would make sense to interpret the game he supervised as presenting a critique of that violence. In this scenario, all the bigotry, discrimination, corruption, and brutality of the game has a political purpose, however awkward and offensive it may be on the surface: it is meant to illustrate the brutal reality that activists—especially women and people of color—are faced with in Belarus.

Although this is the explanation I would prefer to believe, it still wouldn’t be enough to redeem the game. For the ultimate failure of This Is the Police is that it makes everyone culpable but the police. When you fire all the black cops on day four, it’s not really your fault: the racist gangs and evil mayor made you do it. When you order the assaults on protesters, you’re just following orders. If this game is any indication, the worst thing a cop ever did was drink too much on the job: all the true evil originates with the higher-ups and lower-downs.

The aesthetic dissonance caused by this sympathy for the corrupt is most acutely felt in the game’s story. I have avoided talking about the copious cutscenes because they are terrible: a half-baked assemblage of noir tropes and gumshoe clichés narrated by, yes, Duke Nukem himself. But most galling is the fact that, in the middle of all this horrific repression, the game genuinely encourages you to feel sympathy for Police Chief Jack Boyd. Your wife will leave you for a younger man, but you’re better off without her; the mafia leaves pieces of your friend hanging from the ceiling fan, but they think you’re a stand-up guy. By the time Boyd started wooing young Lana, one of Mayor Rogers’ rape victims, I had just about reached my limit. Then I checked the stats: 90 days left to go. Jack Boyd isn’t the only one overdrinking.

///

By day 100, you’re starting to lose sight of the goal. They gave you 180 days to finish out your tenure as chief; at first it sounded like a death sentence, now it’s more like a prison sentence. No matter how many bribes you take, your wallet keeps getting thinner. No matter how many cops you set up to be assassinated by the mafia, there’s always someone snitching behind your back. And when, despite everything, you set yourself to the task of actually administering justice, it seems like everyone is working against you.

So you pop a few more Percocets, throw on that Duke Ellington knock-off you snagged on the cheap, and kick your heels up. Then it hits you: why keep policing at all? If they’re going to fire you in a few months anyway, what have you got to lose? The more you think on it, the better the idea sounds. So you fire all your staff. Every cop, every detective. You stop taking calls from the mayor. When you’re not sleepwalking your way through the faceless exchanges that compose your life, you sit at your desk and let the scanner sing you to sleep.

And nothing happens. No citizen protests about the rising crime rate. No outraged calls from City Hall about dereliction of duty. Hardly a peep from the newspapers. Crimes are still being committed, but somehow, the city doesn’t seem to be falling apart. It’s almost like they don’t even need you.

So you sit up. And you go back to work.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post This Is The Police won’t accept blame appeared first on Kill Screen.

Sit down and hack into the analog world of Quadrilateral Cowboy

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

QUADRILATERAL COWBOY (Windows)

BY BLENDO GAMES

From the maker of Gravity Bone (2008) and Thirty Flights of Loving (2012), Quadrilateral Cowboy (affectionately nicknamed Quad Cow) is the latest vignette game from Brendon Chung of Blendo Games. A story told in the same world as Thirty Flights of Loving, this one focuses on the effects of technology in our experience of culture, careers, relationships, and privacy. Combining the aesthetics and mentality of Y2K with the badass heists of Oceans Eleven, Quadrilateral Cowboy invites players to hack the world around them to pull off some grade-A thieving. This is not your typical lone-gun hacker story, though. Much like Oceans Eleven, there are certain feats you can only pull off when working together as a team. While short and sweet, Quad Cow packs a lot into a short amount of time with simple mechanics that somehow only complicate your world.

Perfect for: Actual hackers, Blendo fans, block people

Playtime: 4-5 hours

The post Sit down and hack into the analog world of Quadrilateral Cowboy appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 27, 2016

Hillary Clinton’s app will make you feel empty inside

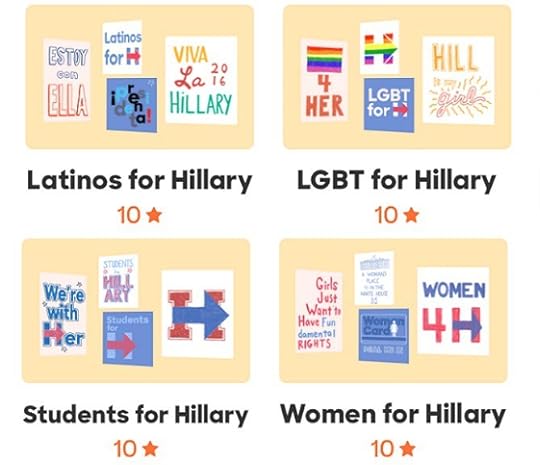

In another attempt to reach out to young voters, former Secretary Clinton’s campaign has released a Hillary 2016 app. The concept is pretty simple: login daily to complete challenges, for which you are rewarded stars/points. You can cash in these rewards for items to decorate your Campaign HQ with. Challenges include quizzes such as the “Trump or False” quiz, which, only by taking the quiz, could I understand wanted me to guess whether Trump or someone else had said a quote. You can decorate the HQ with items as varied as starter, modern, or vintage couches, various “X group for Hillary” posters, and two different colored bean bags.

Giving the app the benefit of the doubt makes it seem, at best, like an attempt to meet voters where they are (the internet). On the other side of the coin, the app appears to be a half-assed toss at one of those things the kids like. Trying to meet voters where they are is a fine motivation. Getting people to think about the election daily is important, even if the kind of people who would download a politician’s app are likely already doing so. The issue, really, is that Hillary 2016 doesn’t get people to engage meaningfully.

There are so many ways a political app could get people involved

There are many ways a Hillary Clinton app could be helpful to her campaign, and to voters. With the recent controversy over the DNC’s attempt to rig the election in Clinton’s favor still fresh in everyone’s mind, having your campaign HQ be a real glimpse into how the campaign is being run could make it appear much more transparent. People view the internet as a democratizing place where everyone has an equal voice, and personal connections can happen across thousands of miles—a political app could lean into these philosophies, creating a sense of community among supporters, and more intimate relationship to the candidate.

Campaigns should make people feel like they are a part of something, and having the “players” vote on questions that Hillary would answer within the app would be a great way to do that. They could select what issue is most important to them to display for others. They could have an interactive Democratic party platform a la Reddit where you upvote and downvote the things you like or dislike. There are so many ways a political app could get people involved, get them to have meaningful political thoughts, and invite them to participate in the campaign without having to leave their homes.

But Hillary 2016 doesn’t do those things. It asks you to take simple quizzes, compare your scores to others, decorate your HQ, and gather useless points/stars (the app creators apparently couldn’t settle on a consistent terminology for their game currency and use both interchangeably).

The Hillary 2016 app may come from a good place, but you can’t meet voters where they are and just stare back at them. They won’t feel engaged, they’ll feel weird. They won’t feel involved, they’ll feel pandered to. Ironically, if the Clinton campaign tried harder to make an engaging app, it wouldn’t look like they were trying so hard. And maybe they’d actually get something back from the people they’re trying so desperately to reach.

You can download the Hillary 2016 app for your iPhone and iPad.

The post Hillary Clinton’s app will make you feel empty inside appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers