Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 85

July 26, 2016

It’s you and your friends against mind-control tech in Signal Decay

The stealth strategy game Signal Decay, previously known as Squad of Saviors, has just made its way to Steam Greenlight. The premise is simple: you wake up one day and the rest of the world has come under the sway of some indomitable evil, so it’s up to you (and up to three of your friends!) to save humanity. Simple. But Signal Decay’s not content to just send you into the shadows and have that be that.

Instead, Signal Decay takes relatively overdone tropes—cyberpunk world, mind control radio, lots of lurking around—and turns it into a strategic experience not unlike XCOM (2012) or Monaco: What’s Yours Is Mine (2013). Described as “stealth action meets rogue-lite,” Signal Decay merges co-op play with intense tactical obstacles, forcing all players to work together in a way that’s a little more advanced than cussing over group chat.

trade off short-term effects for longer consequences

The bases that players will have to infiltrate have reactive defense systems that trade off short-term effects for longer consequences, forcing players to choose their moves carefully in case they incapacitate their team unwillingly after some time has passed. The “rogue-lite” label hints at Signal Decay’s procedural generation, which promises to keep the game replayable for any combination of players.

Though their newest trailer is only a few days old, Signal Decay has already had its share of recognition: finalist at the Independent Games Festival China in 2015, and part of the official selection at this year’s Pax East and Indie Prize, as well as a nomination for “Most Innovative” at Indieplay. It’s been in development for a little over two years, and a postmortem posted on the devblog last June elaborated on what issues often came up, as well as giving an early preview of the pretty digitized graphics that make the current build look so striking. While the early prototype was mostly blue, the newer version uses a whole range of bright colors to mark the player, partners, and enemies as they sweep across the screen in swathes of light, only accentuated by how stark the top-down format looks against a black background.

A week into their Steam Greenlight campaign and Signal Decay are already very popular, with a solid majority voting positively, but there’s still a long way to go before it can see the light of day. Early Access is planned for late 2016, and for now, you can vote them up so that someday your creeping cybernetic rogue-lite dreams can become reality.

Keep up with Signal Decay on Twitter and at their website .

The post It’s you and your friends against mind-control tech in Signal Decay appeared first on Kill Screen.

Flat Heroes turns elegance into a deadly weapon

Flat Heroes is a game about squares in motion, literally. Flat Heroes is a multiplayer-focused game, one that has you controlling dynamic squares that move around a stage, dodging bullets until you can strategically rid the screen of enemies (preferably, all at once). The survival mode can be played with up to four players, either cooperatively or in a versus mode. It’s a simple premise that echoes other games like N++ (2015). But there’s a lot of cool tech running the scenes behind the flat curtain.

the feeling of controlling the little square felt so great

All the art in the game is done by code, rather than sprites or animated renders. This allows the squares to remain smooth and adaptable to any situation—necessary for a game that features the manic combination of platforming and bullet-dodging. As coders, this method was easier for developing studio Parallel Circles than hiring artists to help animate their game. For Flat Heroes the game is all about how it feels.

It evolved from wanting to make a 4-player local multiplayer game. Something like TowerFall (2013). However, the team of two quickly realized how responsive and intuitive their little squares moved around the screen. The movement of the game stood out immediately, and the original idea of an enemy wave mode quickly became incompatible with the game’s play style. However, since the feeling of controlling the little square felt so great, the idea quickly morphed into something of a bullet hell game—the game we can see today.

Flat Heroes recently got a trailer to go alongside its arrival on Steam Greenlight, which you can watch below. It doesn’t currently have a release date.

The post Flat Heroes turns elegance into a deadly weapon appeared first on Kill Screen.

The purpose of Pokémon Go

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

I remember the first time I saw Abney Park chapel. I was already in a state of wonder, having discovered that behind a busy high street, not 10 minutes from my flat, a vast forested cemetery lay silent—cut through with dappled paths, lined with ancient graves. But on top of that, to discover the chapel with its derelict spire, its empty rose window and sprigs of green that grew between bricks and tiles and stone, was to enter another world entirely. Elegant and abandoned, Abney Park chapel seemed to be a rare ruin in London’s busy landscape. To come across it without knowing it was there was a rare pleasure, a discovery from childhood fantasy, an adventure from when the world was big.

So, when on launching Pokémon Go for the first time, I discovered that Abney Park chapel was a gym, with a huge Golbat glowering atop its spire, I couldn’t help but smile. Transformed by this digital overlay, the graveyard would become a dungeon, its winding and confusing paths a potential set of trials for the adventurous trainer. The chapel would make the perfect centerpiece, a dramatic setting for the deciding battle. It was hard not to imagine Abney Park redrawn in the crisp pixel art of Pokémon Red or Blue (1996), or perhaps the utopic colors of the animated TV series. Both had provided rich backdrops for imaginary adventures during my childhood, and the idea that a child now might wander into Abney Park, aiming to conquer the chapel gym, and discover the winding paths, the ancient graves, the dappled ways that appear like paths to other worlds, felt like a wonderful realization of those childhood dreams.

I don’t imagine for a second that I am the only one to have these thoughts. The huge and still escalating popularity and impact of Pokémon Go demonstrates that, for me and others of my generation, this is an actualization of a powerful and long-held fantasy.

READ THE REST OF THIS ARTICLE OVER ON VERSIONS.

The post The purpose of Pokémon Go appeared first on Kill Screen.

Upcoming war game teaches compassion by having you play as your own killer

Lots of videogames depict war, ranging from the gung-ho realism of the Call of Duty and Battlefield franchises, to the completely ridiculous Totally Accurate Battle Simulator. More often than not, these games make you believe you’re the ‘good guy’, even though you just killed a dozen ‘bad guys’ mercilessly to get to your objective. That’s why a small team of five people—James Earl Cox III, Joe Cox, Elliot Mahler, Denver Coulson, and Tyler Stark—decided to create a war game called Our Own Storm that puts you in the shoes of the person who kills you. It’s a way to humanize each character in war, giving you multiple perspectives and seeing how each person deals with the consequences of their actions.

Despite being about real wars, the team behind the game tried to avoid any direct references to any real-world conflicts, in order to avoid inaccuracies and taking sides. However, Cox III discuss the parallels to conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and even the recent failed coup in Turkey, admitting that “it’s hard to not draw comparisons while making such a game.” Instead, Our Own Storm “takes place on the fictional war-torn Isle Tolsia.”

“the player will be on all sides of the war”

In the trailer, you see a group of people being taken to a place surrounded by military police. However, following their approach to naming any specific conflicts or countries, the team has left the backgrounds of these characters to interpretation, since they’re made up of individuals with varying beliefs and values. “Among the soldiers you see, some see the civilians as refugees, others see them as prisoners, and even others might see them as rebels,” Cox III said. On the other hand, you get to choose your own character’s age, family, background, likes, and their future plans.

Our Own Storm’s tagline is “a war game about compassion,” and all of its narrative and mechanical designs are geared towards that. You begin the game as the prisoner—or whatever you might want to call them—and once you get killed, you automatically switch characters to control the killer. “The player will be on all sides of the war: soldiers sieging the city, rebels holding out, and civilians caught in the middle,” Cox II said.

Altogether the game includes four different areas: the sieging army’s camp across the river, the city under siege, the town square, and rural ruins. There is no wrong or right way to die (i.e. to advance the story), because you can get shot if you try and escape, or by “stray gunfire, purposeful gunfire, people trying to protect each other, being scared, trying to survive.” That said, there are parts of the game that you won’t get to explore unless you do die. One example is a level where you are told to sneak into the city behind your commander, as this is where you get a choice: you can obey your commander and stop walking when he does, or you can continue, which will lead to you getting shot in the head by a sniper. If you do the latter, this allows you to take control of the sniper that is located in the second story window, which is not accessible unless you get killed by him.

Our Own Storm promises to reward those who are curious and who want to see what can happen in each scenario. It’s this goal that inspired the team to not include modes or difficulty settings, aiming instead for “a meditative game, one that encourages interpretation and reflection.” Our Own Storm is about 25 percent done, with only the forest area completely finished at the moment. The team is currently working on designing the city.

Our Own Storm is planned to release fully mid-to- late 2017 for PC, Mac and Linux, with plans to bring the game to mobile devices. The game will also make its first public appearance at Dare ProtoPlay festival, August 4th through 7th. Find out more on its itch.io page.

The post Upcoming war game teaches compassion by having you play as your own killer appeared first on Kill Screen.

Gravity Rush 2 promises “new heights” when it drops this December

Gravity Rush (2012) centered on Kat’s self-discovery and personal growth. Gravity Rush 2—which was just announced for release on December 2—is about exploring Kat’s depth and maturity.

A new trailer, released early last week, explores the “new heights” Kat and Raven will come to explore in the Gravity Rush sequel. It’s a glimpse into the massive new world introduced in Gravity Rush 2; a world that promises to take the player and Kat from a tourist to a traveler. There will also be a “bevy of new characters,” including Angel, who’s seen swooping in to help Kat in the new trailer.

SIE Japan Studio promises to reveal Kat’s destiny in Gravity Rush 2—but that’s not all. They’ll also reveal an all-white alternate DLC costume for Kat and the game’s select soundtrack, but just for those who pre-order the game from certain retailers. Pre-orders from the PlayStation store will grant players 10 PSN avatars from the game.

Gravity Rush is getting its very own anime

Gravity Rush 2 creative director Keiichiro Toyama also said more about the anime inspiration in the game. (He’s said there’s a nod to Sailor Moon (1992) in Gravity Rush 2, as well as the look of weirdo superhero Kamen Rider (1971).) Now, he’s taking that influence one step further—Gravity Rush is getting its very own anime.

Gravity Rush the Animation ~Overture~ is being produced by Studio Khara, the folks behind Rebuild of Evangelion (2007). It’s said to bridge the gap between the first game and the second. A release date for the anime series has not been announced, though it’s likely to be released before Gravity Rush 2 arrives on December 2.

Gravity Rush 2 will be available on PlayStation 4. More information is available on the PlayStation blog.

The post Gravity Rush 2 promises “new heights” when it drops this December appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kentucky Route Zero: Act IV is an elegy

Michael Snow’s 1967 experimental film Wavelength is a 45-minute long zoom on an empty room. Outside the walls, and the camera’s frame, the insignificant dramas of human life play out in sad, abortive spirals. Men move furniture into the room; two friends drink and listen to the Beatles; in the end, a man dies on the floor and a woman calmly informs the cops of his corpse.

Snow is monomaniacally committed to his premise: Wavelength is a canonical example of experimental film precisely because of its push-pull between dry, structural formalism and gut-level intrigue. In a way it’s a murder mystery, but one so perversely oblique that it’s nearly drained of mystery at all. Instead we watch the mundanity of everyday existence through a fixed lens, our voyeuristic gaze leaving space for ambiguity, contemplation, disgust, and no small amount of boredom.

Kentucky Route Zero is not merely about drifters, relics, and outcasts

Cardboard Computer’s Kentucky Route Zero has pulled several such feats of watching over its years-long lifespan. A five-part drama that’s equal parts magical realism and Southern Gothic, it’s been doled out act-by-act at a painfully slow pace since 2013. That pace, nonetheless, seems snugly of a piece with the bewildering brilliance it deigns to reveal a little more of every so often. It is not merely about drifters, relics, and outcasts; it drifts itself, and its distance from the pulse of popular culture is impressively vast.

With characteristic nonchalance, Cardboard Computer dropped Act IV on July 19th. There was zero fanfare: it was simply not there one moment, and the next, it was accessible from the game’s resolutely spartan menus. It’s emblematic of the game’s tone overall, which spikes absurdism with dry wit and careful doses of wounding sentimentality, deployed the way William Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor would loose sudden savage violence into the bowels of their fiction.

To wit: Act IV begins with Will, a new addition to the cast, attempting to figure out how to repair a massive mechanical mammoth that sits abreast his steamboat’s bow. The android musician Junebug joins him on the deck as he pores over the mammoth’s manual, and they briefly discuss their journey down the subterranean Echo River.

“Some nights I remember a place, but it’s full of strange new people,” Will says. “And some nights I meet an old friend on an unfamiliar shore. I wonder which kind of night this is.” Later, he says: “I listen to the river’s stories, and my own stories get fainter and fainter.” The game handles these moments of folksy philosophy with the same surety that it handles non sequiturs about bats with “white nose syndrome,” the use of certain herbal teas to lessen the pain of childbirth, or the overarching theme—if you can call it that for its light-footedness—of debt.

Way back in Act I, our protagonist appeared to be shit-luck truck driver Conway, who finds himself forced to take Route Zero to finish his deliveries. Route Zero is a road of unknown provenance: the sections where you drive around to different locations are even rendered in a barely-there latticework of wireframes, as if Conway has found his way into a place where the world has yet to finish knitting itself together, and the boundaries between reality and everything outside are thin as spiderwebs. But Conway’s bum leg and entanglement with a shady firm of glowing skeletons who strong-arm him into delivering their own goods have become but one note in an ever-growing chorus. Act II introduced Ezra, whose brother Julian is a massive eagle, and Act III gave us the androids Junebug and Johnny, among others.

Route Zero is a road of unknown provenance

Junebug stands out because of the visceral power of a scene where she performs a song at a bar called the Lower Depths. As Junebug’s wrenching, inhuman warble spools out the words of your choosing, the club around her peels away to reveal the moon and stars sparkling above. The camera begins to slowly, slowly pan back and forth; Junebug sways to the insistent, pulsing beat. And then the roof drifts back down onto the club, piece by piece. like dropped scraps of paper, and celestial incandescence is replaced by flickering florescent lights and the hum of shitty wiring. There is no moment like this in Act IV. Instead, Act IV is humbler, content with formal elegance and the simple pleasure of moving our protagonists’ stories forward.

From the get-go, the cinematography shows new confidence. The scenes aboard the boat, the Mucky Mammoth, pan and track along its interior and exterior in ways that feel substantively, technologically new for Kentucky Route Zero. A later scene where Ezra and the boat’s captain Cate pick mushrooms on a small underground island of cypress trees experiments with pairing a long shot and dual strands of prose—they both describe the characters’ actions and relay hazy memories. That the appearance of a derelict Civil War ship called the Iron Pariah, full of wailing cats, drifting huge and silhouetted past the camera feels not like an intrusion but the scene’s natural emotional peak is proof enough that Cardboard Computer really fucking know what they’re doing.

But do we know what they’re doing? And do we need to? Kentucky Route Zero has always skirted the boundaries of surrealism-for-surrealism’s-sake, but grounded itself early on with a focus on the physical and mental tolls of debt and poverty. We watch these characters navigate the pitted wreckage of their lives, our decisions meant not to guide their actions but to illuminate them as people. “What do you want to know?” the game asks, and lets you answer.

There are several points in Act IV where you explicitly have to decide to keep digging. Conway’s travel companion Shannon finds a stash of increasingly bizarre VHS tapes aboard the Mammoth. If you watch them, you watch her sitting in a chair, watching them. You can watch as many as you want, or none at all. Some are inexplicable; some are boring as shit. One appears to explicitly reference Wavelength.

Later, a character checks his answering machine. Again you can opt to listen to every last inane message. In a narratively adventurous interlude, you comb through surveillance footage of the protagonists from some time in the future. These are not grave moral choices; they are an invitation to empathize, to uncover some small hard fragment of someone’s life.

Act IV confronts us with scenarios that test and limit our perception

The game’s dialogue options have always been in the third-person, distancing us from the speaker, but more and more Kentucky Route Zero impresses that we don’t really know its cast of characters. Even they are becoming strangers to themselves: “I can’t feel at home in this world any more,” goes one song by the game’s recurring troubadours/Greek chorus, the Bedquilt Ramblers. Conway, once the focus of this story, becomes unknowable—we play largely from the perspective of his companions, and his behavior is erratic and worrying. While watching a theremin virtuoso named Clara (like Conway, her name is an uncharacteristically direct allusion), you sift through a conversation between Johnny and Junebug, entwined with memories from the last time they watched Clara play. In ghostly italics, one line stands out: “That’s the thing about the theremin—it’s the only instrument you never touch.”

From the room of VHS tapes, to the security footage, to the bat sanctuary, to the theremin performance, to the camera’s final, extended retreat up the rickety helix of a spiral staircase; Act IV confronts us with scenarios that test and limit our perception. Like Snow’s Wavelength, it gives us just enough to trick us into feeling like we’ve glimpsed something real.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Kentucky Route Zero: Act IV is an elegy appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 25, 2016

New videogame gives you a tough course in capitalist theory

Colonialism, public debt, expropriation. These are what Karl Marx called primitive forms of accumulation; the spark that ignited the flame of capitalism. In David Cribb’s Crisis Theory, you are that flame. You are the spirit of capitalism.

Capitalism, as outlined by Marx, is defined by the accumulation of capital—that is, pursuing profit, and at whatever cost necessary. Cribb’s new game is a representation of that process. First, there is the initial investment of capital into labor power or a means of production. Combined with technology, a commodity is created; a commodity that must be purchased by workers or capitalists if a profit is to be rendered. Any profit is then pumped back into the initial capital pool to continue the process.

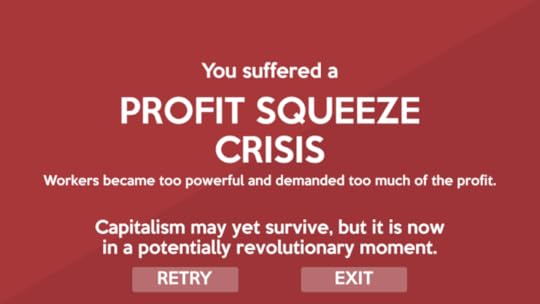

As capitalism, you’ve got one goal—profit. It should be simple, no? Here’s a spoiler. It’s not. As Cribb pointed out, capitalist theory is filled with contradictions. And those contradictions are the core of crises facing you, capitalism. There are five buttons to push in Crisis Theory—just five buttons to prevent your central process from falling into crises, and giving the people the power to revolutionize the system.

expertly demonstrates the crisis in Marx’s theory of accumulation

With these buttons, you’ll manage how your means of production and labor power align. When you’ve depleted your resources, you’ll push a button to harvest more. Another button encourages the State to provide a boost to workers or the capitalist reserve. And if those aren’t working, you’ll look back to primitive accumulation—colonialism, public debt, and expropriation.

The speed at which the process runs increases as the game continues. Things move quite slow, at first—though, the rate at which it speeds up quickly becomes overwhelming, and you’ll have to start making choices. But even then, you can’t win this game. You’ll eventually fall into one of four crises: a natural crisis caused by exploiting natural resources, a profit-squeeze crisis if your workers become too powerful, a falling rate crisis for spending too much on means of production, or an effective demand crisis when your workers can’t afford your commodities.

Crisis Theory expertly demonstrates the crisis in Marx’s theory of accumulation. It’s a topic many books have covered, though it seems particularly suited for a videogame. “The increasing speed and volume of capital circulation sort of acts as an in-built difficulty curve,” Cribb said. Even for folks familiar with Marx and his writing, experiencing the chaos of the process may be pretty alarming.

However, Cribb’s game isn’t exactly for those entrenched in Marxist theory. “I’m sure [scholar] Andrew Kliman would disagree with the role I gave the tendency of the falling rate of profit in Crisis Theory,” Cribb told me. However, he’s not convinced Crisis Theory will persuade a general audience to become Marxists, either. Cribb is more interested in drawing in “leftists who haven’t really dived into theory.”

“Hopefully the game can provide a general outline of some of the key contradictions in capitalism, and ideally encourage people to go back to the source material for a more detailed and more nuanced understanding,” he added.

As Crisis Theory continues—10 minutes, if you’re lucky—you may find yourself clicking helplessly on the primitive accumulation button for any relief from the madness. It’s the button that functions as the starting point, but also as a way to increase the amount of capital in circulation, though it comes at a cost. Namely, imperialism. Or colonialism, or public debt, or expropriation. I found myself clicking tirelessly through these options, aiming to land on the least evil sounding one available.

But that’s not really the spirit of capitalism, is it?

Pay what you want for Crisis Theory, which is available on itch.io .

The post New videogame gives you a tough course in capitalist theory appeared first on Kill Screen.

The videogame that helped popularize Japanese mecha in the west

In the early 2000s, the Japanese government started to evaluate the value of the country’s popular culture industry following international successes in anime/manga such as Pokémon and Dragonball, videogames like Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda and Super Mario series, and films including Spirited Away (2001) and Ringu (1998). Realizing that its cultural influence expanded despite the economic setbacks of the Lost Decade (from 1991 to 2000), Japan sought to promote the idea of ‘Cool Japan’, an expression of its emergent status as a cultural superpower.

For the next dozen years, the Japanese government made use of its soft power and ‘Cool Japan’ strategy to boost cultural exports from its creative industries, including one of its oldest and most influential anime genres: mecha (an abbreviation for the English word ‘mechanical’).

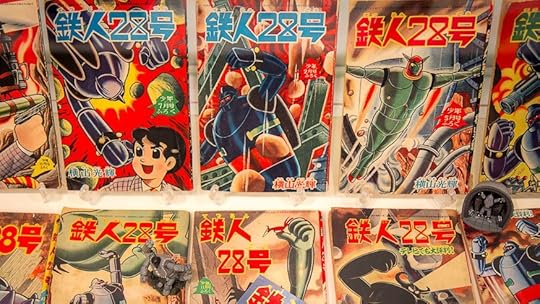

The origins of Japanese mecha can be traced to the end of World War II, when Japan witnessed the destructive power of modern technology in the form of atomic bombs that obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. During Japan’s Occupation and post-Occupation years (1945-early 60s), an explosion of artistic creativity occurred in the manga industry, possibly aided by the medium’s exclusion from U.S. Occupation censorship policies. One artist, Mitsuteru Yokoyama, took advantage of this loophole to craft one of the most influential mangas of all time.

Yokoyama was motivated to become a cartoonist following the breakthrough success of Osamu Tezuka’s Mighty Atom (Astro Boy, 1952), the story of an android who fought crime with mechanical powers yet was capable of displaying human emotions, essentially acting as an interface between man and machine. Yokoyama took a different approach, drawing heavily from his childhood encounters with war, technology, and film.

The result was Tetsujin 28-go (Iron Man No. 28, 1956), a parable about technology’s dangers and benefits. It told the story of Shotaro Kaneda, a boy detective who fought criminals by commanding the titular robot by remote control. Their adventures were depicted in fast-paced, action-filled panels reminiscent of a well-edited action film.

Much of Tetsujin 28-go’s appeal could be attributed to the strong bond between Shotaro and Tetsujin, enhanced by the robot’s benign and knight-like design, suggesting an avatar of unstoppable justice. Tetsujin 28-go was the first instance of a Japanese cartoon based on the idea of a giant humanoid robot controlled by a human being, with the former acting as a tool for the latter to use for realizing his fullest potential. This concept could be seen as a metaphor for a resurgent Japan, reawakening like a giant from the rubble of WWII.

Man-machine union

If Yokoyama established a link between man and machine with Tetsujin 28-go, then Go Nagai forged that link into a union. One day, while waiting to cross a street, Nagai contemplated the backed-up traffic and mused about how the drivers were wishing for some way to get past the other cars. This inspired a novel idea: what if the car suddenly transformed into a robot that a person could ride and control like a regular vehicle? Nagai’s concept—a pilot sharing the body of a robot—made the man-machine bond both figurative and literal. The resulting manga, Mazinger Z (Tranzor Z, 1972) would prove to be the next big evolution in the mecha genre.

Mazinger Z told the story of Koji Kabuto, an orphaned schoolboy who stumbles upon the titular giant robot in his grandfather’s secret lab. The robot’s name evoked the image of a majin (demon god) with its similar-sounding syllables (‘Ma’ meaning ‘demon’ and ‘Jin’ meaning ‘god’), reinforcing the idea of a machine built by humans in need of protection that also appears as an ancient, unfathomable being.

symbiosis between man and machine

Mazinger’s appearance was striking for its time: a brightly colored mechanical juggernaut ornamented with a mixture of military equipment and samurai armor. Its design resembled the sleek new roadways, bullet trains, and skyscrapers being built in Japan during the 1970s. A small hovercraft docked on the robot’s head housed Koji, who acted as its ‘brain’. This established Mazinger as an extension of the pilot’s abilities and will, symbolizing a powerful symbiosis between man and machine.

Before the decade ended, another development in the genre appeared that surpassed Nagai’s work. Created by Yoshiyuki Tomino, Mobile Suit Gundam represented a massive shift in both tone and scope. In place of isolated weekly episodes, Gundam presented a continuously developing story with a more ambiguous sense of morality that targeted the lines between good and evil and the effects of war on the people who fought. Instead of humans using machines to fight off evil aliens, Gundam had humans fighting humans, with both sides having their own ideological motivations. This new approach led to the splintering of the mecha genre into two subgenres: Super Robot and Real Robot.

Whereas Super Robot stories focus on near-godlike mechs in fantastical scenarios, the Real Robot subgenre emphasizes drama, human characterization, a realistic civil-war-in-space backdrop, and plausible mech creations that required adjustments and repairs. This could lead to moments when the protagonist might actually lose a battle if their machine was not properly operated and maintained. This, again, is in contrast to Super Robot works, which depict mechs as near-invincible entities that only seem to sustain damage when needed to drive the plot.

Unlike clunky, lumbering Western mechs, Japanese mechs were anthropomorphic and highly mobile entities. They espoused recognizable classes of people—snipers, soldiers, knights, etc.—including symbols of Japanese culture like the samurai. This can be seen on the RX-78-2 from Mobile Suit Gundam, which sported a fluted helmet and a skirt of armored plates on its torso.

Motion was equally important. Like the samurai sword, the mobility of Japanese mechs was managed by the user within, whose own bodily control and prowess determined the mech’s amplified analogues of human action. This granted the mechs a striking agility as the humans inside the mechs became empowered. The Japanese mecha philosophy promotes the idea of having people work alongside humanoid machines, a desire associated with Japan’s long religious history and culture.

Much like the Western superhero genre, with characters such as Superman inspired by Judeo-Christian ideals of an anthropomorphized God, the Japanese mecha is influenced by East Asian religion. Both the Shinto concept of revering natural phenomena as kami (gods) and the worshipping of carved images of Buddha in Japan suggest the protean notion of inner energy that can manifest itself in a mechanical form that may showcase some human traits. This is the Japanese mech’s most distinctive characteristic: it is the tool through which its pilot expresses their power and will to overcome by bonding with the machine. This union imbues the mech with a ‘soul’, gratifying both the pilot’s need and the viewer’s fantasy of technological power, authority, and competence.

Shogo: Mobile Armor Division

Shogo: Mobile Armor Division offers an example of a Western first-person shooter that captures the thrilling essence of Japanese mecha works like Patlabor and Venus Wars by combining speedy mechs with the fast-paced gameplay of Doom (1993). Released in 1998 by Monolith Productions, Shogo puts players in the shoes of Sanjuro Makabe, a wise-cracking commander in the United Corporate Authority, who is emotionally recovering from an accident that killed his brother Toshiro and childhood friends Kura and Baku.

From the outset, Shogo displays many of the characteristics of anime. On booting up the game, the player is treated to an anime-style movie sequence, accompanied by a Japanese pop song that was developed from rough drafts received from a Japanese publishing company. The lyrics embody typical anime themes of courage, perseverance, and optimism, idiomatically juxtaposed with the over-the-top action shown on-screen.

The audiovisual design is equally noteworthy. Unlike other 3D games released in the late 1990s, Shogo adopts a distinctively anime-inspired art style for its characters, visual effects, and environmental props. The large, bright eyes of the characters, grandiose explosions, and in-game mock advertisements are characteristic of the anime aesthetic, as are the cheesy one-liners, hand-wringing angst, and cocky humor of the dialog. This is especially apparent in Sanjuro’s conversations with allies like Kura, and foes like Samantha Sternberg, a Fallen soldier who repeatedly assaults Sanjuro throughout the game:

Kura: “Watch my ass!”

Sanjuro: “My pleasure.”

Kura: “You say the sweetest things!”

Samantha: “We meet again!”

Sanjuro: (After defeating Samantha for the third time) “I think you need to get over this obsession; it’s not healthy.”

But Shogo’s anime influences go deeper. Upon close inspection, references to several popular anime series become evident. In the second level of the game, the names of certain characters are borrowed wholesale (e.g. Isamu Dyson from Macross Plus, Rick Hunter from Robotech, Noa Izumi from Patlabor). Posters and billboards for ‘CURV’ and ‘War Angel’ directly allude to Neon Genesis Evangelion and Battle Angel Alita respectively.

In addition to its audiovisual design, Shogo displays strong mecha anime influences in its narrative, which is appropriately chaotic, conspiratorial, and convoluted. The plot contains many sudden twists and turns that leave Sanjuro questioning his alliances and objectives as he is caught in a conspiracy that will determine who gains control of Cronus, the mineral rich planet on which Shogo takes place, and its resources.

appropriately chaotic, conspiratorial, and convoluted

The tone of Shogo leans heavily towards Gundam and Real Robot. The United Corporate Authority (UCA) intergalactic security forces, the Cronian Mining Consortium governing body of Cronus, and the Fallen paramilitary terrorist group all have their own legitimate reasons to fight one another. The Fallen, in particular, become less antagonistic in the eyes of the player through a late-game revelation that unveils the Fallen’s raison d’etre: to front the interests of a superbeing known as Cothineal. This underground creature is the secret source of the precious kato ore that litters Cronus, and is trying to regain freedoms accidentally stolen from it by the colonizing conglomerates.

Further complications arise from Sanjuro’s commanding officer who gradually becomes irrational in his attempts to eliminate the Fallen. This places Sanjuro in a dilemma he must deal with near the end of the game when given the ability to choose one of two paths: either bring the religiously zealous Fallen leader Gabriel to justice, or help him seek a truce with the UCA to put a peaceful end to the conflict.

All of these audiovisual and narrative elements serve to imbue Shogo with a distinct mecha anime ‘feel’ that balances drama and playfulness, a feat made all the more impressive by the game’s Western origin. But Shogo’s real appeal and biggest nod to the mecha genre lies in the four Mobile Combat Armor (MCA) suits that players can choose from and pilot throughout their adventure.

The MCAs in Shogo: Mobile Armor Division reflect the aforementioned Japanese philosophy of suggesting combat classes, such as the Akuma’s ‘scout’ look and the Predator’s ‘assault’ design, and display a mix of Real and Super Robot elements. On one hand, the MCAs reflect their industrial origin through the name of their manufacturing firm (e.g. Andra Biomechanics) and classification numbers (e.g. Mark VII). On the other hand, two of the MCAs bear Super Robot-style names that refer to malicious supernatural beings: Akuma means ‘evil spirit’ in Japanese, and Ordog is Hungarian for ‘devil’.

The mecha anime influences can also be felt in Shogo’s high-octane gameplay. Unlike most ‘90s mecha videogames, Shogo married its mecha theme with first-person action inspired by id Software’s Doom and Quake. This choice of perspective allows the player to ‘become’ the pilot/MCA, cementing the man-machine bond as they navigate battles filled with visual flourishes typical of mecha anime. These include the trading of shots while closing in and circling hostile mechs, ‘Itano Circus’ missile swarms (named after the animator Ichiro Itano who pioneered the effect in Macross), and massive explosions that fill up the screen. Each firearm offers unique particle effects that serve to further evoke the dramatic combat seen in mecha anime series like Robotech and VOTOMS.

While inside an MCA, Sanjuro is capable of performing virtually all of his on-foot moves, including crouching, jumping, strafing, picking up and switching firearms on-the-fly, hovering, and even swimming. This allows Shogo’s MCAs to mimic the speed and nimbleness of conventional first-person shooters like Unreal Tournament (1999) and Rise of the Triad (1994).

The high level of mechanical maneuverability brings up another important aspect of Japanese mecha design: the notion of the mech as ‘body armor’, intrinsically connected to the human body. While Shogo’s MCAs express mechanical agility and technological prowess, they also display human elements in their design that go beyond their anthropoid architecture. When shooting an enemy MCA, for instance, hostile mechs stagger and recoil as if alive, making the MCA more of an exoskeleton than a bipedal tank by reinforcing the identity of the mech and its pilot.

Sanjuro is sometimes accompanied by two friendly MCAs on his missions, recalling the three-unit teams found in mecha series like Special Armored Battalion Dorvack and Metal Armor Dragonar. This archetype reinforces the fact that the player is just another cog in the war effort, despite their character’s high military ranking. Like Noa Izumi from Patlabor, Sanjuro is not a child prodigy endowed with superhuman abilities or enhanced reflexes. As such, Sanjuro still needs to watch his back while engaging similarly skilled opponents.

mixture of Eastern themes and Western game mechanics

This idea of an even playing field is reflected in Shogo’s critical hit system, which came directly from Japanese role-playing games. Although this system allows the player to occasionally deal more damage than usual and earn a health bonus when scoring critical hits on enemies, the system also grants these abilities to enemies. The player cannot afford to let their guard down, particularly since Shogo’s battles pit the player against multiple adversaries. When one-on-one fights do occur, it is against stronger foes like Ryo Ishikawa, the game’s antagonist, who fills the role of the rival pilot, much like Code Geass’s Suzaku Kururugi. The differences between ‘regular’ and ‘mano a mano’ combat are tied to the player’s level of improvisation and choice of combat approach. These elements reflect the game’s focus on the ability of the player, and not on the technological capacity of their MCA.

By transplanting one of Japanese pop culture’s most iconic media forms to the quintessentially Western first-person shooter genre, Shogo gives the player the opportunity to experience firsthand the chaotic action and drama typical of mecha anime, and live out their own power fantasies by ‘becoming’ the pilot/machine. Through the game’s use of the first-person perspective, the inputs of the player, motions of the robot and emotions of the pilot become one. This seamless mixture of Eastern themes and Western game mechanics makes Shogo a distinctive achievement. It actually feels like an interactive version of an over-the-top mecha series, a testament to Monolith’s strong understanding of Japanese mecha.

The future of mecha

Nearly 20 years following Shogo’s release, the mecha gaming scene has grown increasingly more diverse over time. Games like Steambot Chronicles (2005) and Xenoblade Chronicles X (2015) spiced up their role-playing formula with mechanized gameplay, titles like Zone of the Enders (2001) and Strike Suit Zero (2013) feature fast-paced combat in wide-open spaces that allow for multi-angular movement, and releases like Hawken (2012) and Titanfall (2014) adhere to the same first-person shooter formula that has powered Monolith Productions’ take on the mecha phenomenon. This wide-reaching expansion of the mecha genre showcases a desire by game studios to emulate the thrills and/or explore the themes of mechanized combat from various design and gameplay perspectives. With upcoming mecha-themed titles like the Kickstarter-funded Battletech, Muv-Luv, Titanfall 2, and PlayStation 4/Xbox One port of Hawken, and rumors that From Software is possibly working on a new Armored Core installment, the mecha gaming landscape shows no signs of withering or stagnation.

But for all the gaming developments that have expanded and fostered the mecha scene, Shogo still manages to stand out from the pack by remaining the only mecha title, and one of the few games overall, to seamlessly blend Eastern cultural elements with quintessentially Western game mechanics, which results in the game possessing a unique “spark” derived from the essence of both its mecha anime and first-person shooter influences. Such a spark imbues the entire experience with a peculiar sense of character seldom seen in games—let alone mecha titles or shooters in general—one that cheekily accentuates its Japanophilic charm with the wanton gore and destruction emblematic of old-school, arcade-style shooters like Doom and Quake, which in turn fuels the pilot/robot bond already made conspicuous by Shogo’s first-person perspective.

It is such that now, rather than trying to split the cultural distinctions of art forms from different countries, game makers can travel across the world taking bits and pieces of things they learn and enjoy, and then glue them together in their work to expand their creative possibilities beyond the confines of their native culture. Through this unique philosophy, the multifaceted mecha genre can provide a slew of games that make use of distinct perspectives to portray mechanized warfare in a novel and intriguing light.

Shogo: Mobile Armor Division is available on GOG.com .

The post The videogame that helped popularize Japanese mecha in the west appeared first on Kill Screen.

Protest your innocence in a new nonlinear courtroom drama

Bohemian Killing, released last week on Steam, is a game about being guilty. More specifically, it’s a game about being guilty and then convincing a court of law that you’re not. A courtroom drama that wants to avoid both Phoenix Wright camp and Law & Order plodding dullness, the main draw of the game is not discovering who committed murder or why, but instead constructing a lie believable—or not—enough to exonerate yourself. Your past is known; your testimony is malleable, and eager to be manipulated. If a blatant lie won’t do, sift through the evidence and twist it to your own desires, and if that’s not enough claim provocation, or coercion, or insanity. The jury is listening.

the mainstage act of lying flagrantly and gloriously under oath

Where many games would leave the player’s past actions up to hearsay—amnesia is highly contagious among protagonists these days—Bohemian Killing’s explicit guilt gives it meat, with nothing to draw away from the main act of lying flagrantly and gloriously under oath. You may have had good reason: Marcin Makaj, the designer, hinted in an interview with us in 2014 that though guilt is certain, motive is far from clear.

However, this doesn’t seem like a game that’s keen on getting one to confess. A solemn backstory and admission of guilt may be satisfying to watch, but to play, what can beat the tangled layers of excuse over excuse over excuse? After all, you get to watch these lies be born into truth as you play, your actions narrated by the protagonist at trial (voiced by experienced VA Stephane Cornicard) in a way reminiscent of Rucks’s narration in Bastion (2011). If you’re convincing enough, the court might believe anything.

Secondary to the plot–or lack of it, or abundance of it, depending on how creative you get—is the setting. Paris in the late 19th century with a steampunk twist. Racial tension and class differences feed into the cultural climate, some of which is implied to have led to the unfortunate predicament the protagonist finds himself in. Whether his intentions were noble or twisted is yet to be seen.

Bohemian Killing is out now on Steam and looks beautiful, but will the court be able to look past that beauty and decipher the blood on your hands? Jury’s still out.

The post Protest your innocence in a new nonlinear courtroom drama appeared first on Kill Screen.

Enter a dreamland of glitchy, corrupted videogames

Two fighters behind a curtain of pea green. A bobsled dives into a sea of broken pixels, tumbling into a geode-like fractured structure far removed from the icy-whiteness of the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City in 2002. The frenetic golden glory of Fantastic Dizzy (1991). These and more make up the Tumblr blog known as Corruption as Art, a compilation of classic videogame glitches that promises “art through computer generated chaos.”

“I was originally drawn into doing this by my desire for tinkering and watching things fall apart, not by any sort of aesthetic,” the creator of Corruption as Art told me. The glitches come from a variety of games from Final Fantasy VI (1994) to the aforementioned Fantastic Dizzy, and span all sorts of consoles. Using the corruption tool BizHawk, the blog’s owner corrupts the games in real time: “Basically that means that instead of corrupting a file once, it continually changes data in either the game’s data or the system memory.”

GIFs that wink from hacked emulators of a bygone era

This allows for more on-the-fly GIF creation and for greater variability since the creator doesn’t have to continually alter the game’s data to create interesting gifs: “[the real time corruptor] eliminated a lot of tedium and frustration that comes with most rom corruption tools… As a result of my process, I have the luxury to pick and choose which corruptions I want to show on the blog, and there’s a lot of stuff that ends up on the cutting room floor.”

The result is a multitude of fractured games, glittering GIFs that wink from hacked emulators of a bygone era. You can see the corruptions for yourself on Tumblr.

The post Enter a dreamland of glitchy, corrupted videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers