Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 77

August 10, 2016

Videogame series aims to humanize the victims of sex slavery

Sex slavery is a difficult topic to discuss, and one that can be challenging to turn into a videogame. Inflatable Reality, a team of experimental game developers led by Brian Schrank, has attempted to do just that with a set of four games chronicling the experience of a Cambodian sex slave. Known as A Moment Free From Darkness, the experiences span four different technologies and game types in an attempt to grow empathy between the viewer and the life of the young woman being depicted.

The game is inspired by Schrank’s experiences living abroad and talking with women afflicted with the situations his games entail: “I lived in Cambodia for almost a year and paid prostitutes to teach me Khmer.” A Moment Free From Darkness is designed to highlight the experiences of the women and girls Schrank met in Cambodian brothels and on the streets, women who he views as being incredibly resilient and underserved by a privileged community. “These slaves need our help and deserve our admiration for persevering through a chain of traumas: being sold by their parents, shocking violence, coercion, endless physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, pregnancies, and STIs including HIV and AIDS.”

The four experiences that Schrank uses to express these emotions and circumstances span four unique platforms: mobile, PC, VR, and Apple Watch. Games 1, 2 and 4 are focused on empowering the character, and showing her engaging in the titular moments free from darkness—from imagining changing the color of her fingernails to adjusting the fringe on her dress. The third game, however, places the player into the perspective of the girl during the act of her own rape at the hands of a paying customer.

Schrank hopes to humanize their experiences

Focusing on the vibrancy of the women affected, and then highlighting the grotesque nature of their experiences, Schrank hoped to avoid the pitfalls of other serious games: “Most serious games feel flat and easy to emotionally dismiss because they are overly didactic, focusing too much on educating players about the underlying systems of a given topic rather than humanizing and subjectifying the experience of navigating such systems. So instead I hope to generate empathy, respect, and a subjective connection to these girls and women as they persevere through the abuse by creating their own moments of feeling centered and healing.” Placing the player into the lives of these women, both in their darkest moments and in the little slivers of happiness throughout the day, Schrank hopes to humanize their experiences for people who will never have similar moments of their own.

You can find out the information and downloads for all four games at the A Moment Free From Darkness website. If the plight of the young women profiled by Schrank’s game speak to you, he points to more action that you can do: “Many organizations fighting slavery are limited to the ‘educate, pray, and donate’ trend. One of the best organizations going beyond that is End Slavery Now. I asked them what we could do and they shared their action library (updated weekly) that can be sorted so you may specifically choose to fight sex trafficking if you wish.” You can find more about End Slavery Now at their action library online.

More on A Moment Free From Darkness can be found on its website.

The post Videogame series aims to humanize the victims of sex slavery appeared first on Kill Screen.

Wobbledogs is even more ridiculous than it sounds

My favorite Dwarf Fortress (2006) update briefly describes the elimination of a bug wherein cats were ”dying of alcohol poisoning after walking over damp tavern floors and cleaning themselves.” The causal logic that leads to an issue like that is both immediately understandable and completely ridiculous. These sorts of unintended consequences are at the core of games that rely on random interactions to tell stories and create characters. The generating algorithms have to be precise and functional to produce readable results, but if there’s just enough noise, things get weird and funny with it.

Tom Astle is working on a project called Wobbledogs that combines the fun of watching computers try to tell you what dogs look like with the fun of watching dogs do, well, anything. My real dog steals shoes and the occasional vegetable. Astle’s virtual puppies had an issue where they “would kick [small food objects] as they walked up to them and get stuck in a loop of chasing them around the pen.”

as adorable as it is horrifying

“It was pretty funny,” he says, “but also a great way to guarantee that all the dogs [would] starve.”

His ultimate plan for the game is to allow the player to breed and train a multitude of goofy-looking dogs. Nintendogs (2005) is plenty of fun, but it’s pre-packaged, and sterile—Astle’s game is as adorable as it is horrifying. The face painted on every dog has enormous eyes and teeth. Wobbledogs is also intensely specific, with every interaction controlled by physics or the dogs’ different desires. Astle writes, “Every time I add something I try to think about how it could play into dog uniqueness.“

Dog’s appearances are defined by “genes”—a long string of 1s and 0s that are translated into fur colors, leg lengths, widths etc. Over the course of the hilarious breeding process those values can “mutate” (by flipping from a 1 to a 0 or vice versa) and produce a slightly different dog, meaning you can select for or against certain traits. Behaviors, meanwhile, can be trained with scolding and rewarding based on what you want to reinforce. Dogs have rudimentary memories, too, so they might pick a favorite spot to sleep, or figure out where you always place the food.

Reading what Astle has to say about his goals, successes, and failures is a great time, and it’s peppered with excellent GIFs of dogs flying through hamster tunnels or waving their bendy sausage bodies and big ol floofy tails around. For real, just look this little monster dog in its terrified little face and tell me it is not the cutest mistake of virtual genetics you’ve ever seen.

You can follow the outstanding Wobbledogs devlog on TIGSource.

The post Wobbledogs is even more ridiculous than it sounds appeared first on Kill Screen.

I Am Setsuna is cold at heart

I grew up with JRPGs, but not in the sense that most people grow up with them. My mom always played them, and I always sat perched, cross-legged in our quaint apartment, happily petting our cat and watching her exciting journeys unfold. Mostly, it was the Final Fantasy games, but sometimes we’d fit a Sonic the Hedgehog session in. My mom was only 21 when she had me. She was a single mother who simultaneously juggled raising me, going to college, and working part-time. Videogames became her only hobby—they were an escape from her stress-inducing reality.

JRPGs, especially those of the 1990s, offered grand magical worlds for my mom to hop into. They were emblematic of adventure, pulled along by a simple goal for my mom to follow. All their stories were basically the same, with obvious twists and turns coming in from a mile away. But the plot never really mattered as much as the endearing characters and the sense of spectacle that came with exploring their worlds. Tokyo RPG Factory’s I Am Setsuna takes inspiration from those beloved JRPGs of yesteryear, most unabashedly from Chrono Trigger (1995), but loses sight of its inspirations’ most important qualities.

Bearing no personality or liveliness of its own

I Am Setsuna begins in a familiar way. You play as masked mercenary Endir, an atypically voiceless protagonist, who is ordered to kill a girl bound by fate to be sacrificed for the Greater Good (or, stopping monsters from taking over the world, as usual). You make an attempt on her life, but the girl, the titular Setsuna, talks you out of it. From then on, you join her Sacrificial Guard and embark on a journey to the ominous Last Lands, meeting new companions along the way. The story’s fine. It’s simple and somber. But while I Am Setsuna gets the generic aspects of classic JRPGs right, it skips over nearly everything else that made JRPGs of its time so memorable, bearing no personality or liveliness of its own.

This is especially deplorable as I Am Setsuna is concerned most of all with trying to evoke JRPGs from the 16-bit era. These are games where dialogue and dynamics between characters brought the stories to life, and almost only that. Older JRPGs didn’t have the luxury of graphics that could effectively animate a character to life, or even necessarily a striking art style to complement each personality. Instead, these characters had to stand out through mere dialogue boxes and how they interacted with one another. But I Am Setsuna apparently didn’t get that pointed memo, sticking with bland, cookie-cutter characters through and through. When I think of the JRPGs I watched unfold in front of my mom and I, I see Terra narrowly surviving the final battle against Kefka in Final Fantasy VI (1994), Sephiroth’s betrayal in Final Fantasy VII (1997), and I remember thinking Squall was kinda annoying in Final Fantasy VIII (1999). Now, located as I am on the other side of I Am Setsuna, I’m straining to think of any single scene or character that left even a trace on my mind.

Yet, there are still brief glimmers of warmth in I Am Setsuna. Sometimes your quirky magical companion Kir will say something silly or brash, and everyone will knock their heads back in coordinated, silent laughter. And, for a moment, maybe I’d smile. At one point in the game, the gruff warrior Nidr has his secret past revealed, and it’s genuinely heartbreaking. Yet, his painful past is quickly glossed over in favor of the less interesting journey at hand, and is hardly brought up again. I Am Setsuna doesn’t give its supporting party members a chance to shine, as the great JRPGs of the past did, nor does it deliver on the illusion of choice that the player is seemingly given. I personally played Endir as a dick the entire game because I thought it was funny, which would often draw gasps from my companions. Sometimes Setsuna would sadly say something to the effect of, “That’s so unlike you,” which never made sense because I always chose the rude option in a dialogue branch. It just didn’t seem like her, or her companions, were ever listening to the mean Endir I had orchestrated from the start. It never felt like the dialogue—with or without choices given—had any weight.

One of the enduring appeals of JRPGs that I Am Setsuna also neglects is that of exploration. The varied lands of any 16-bit JRPG, like the overworld and underworld of Final Fantasy IV (1991) or the sci-fi musings of Phantasy Star IV (1995), feed into the game’s sense of adventure. Because really, what’s an adventure if you’re not going to new places? Yet, somehow, I Am Setsuna abandons this well-loved trait, with every town a remix of the same basic template, and a dreary piano soundtracking its entire 20-something-hour journey. There are only two towns that look wildly different from all the others before them—and one is only accessible near the end of the game, once you get a handy-dandy airship (this is a JRPG, afterall). At rare times, some of the dungeons manage to avoid the buried existence of the others, all of them found within snowy mountains or ice-governed caves. Unfortunately, the diversity in environments ends there. Setsuna and her guards’ journey ends up not feeling like an adventure, but a never-ending slog through chilly, familiar territory, skirting a world much bigger but never quite reaching it.

A game so dedicated to trying to make you feel sad

Winter is commonly an analogy for sadness. For instance, Kanye West notably used the cold as a motif for his 808s and Heartbreak (2008) track “Coldest Winter,” an ode to his late mother. Winter is often emblematic of a trying time in one’s life—one that’s incessantly cold and harsh, like your feelings when you’re blue. I Am Setsuna grabs the winter motif and runs with it: everywhere in the world is covered with snow. It’s breathtaking at first, and successfully sets the tone for the game until you realize that every new island and town you travel to embodies the boundless sleet. It’s a game so dedicated to trying to make you feel sad (since this is a game about leading a girl to her sacrificial death), that it drops you into a perpetually snowy world to match the dreary tale it weaves at nearly every turn. If this sounds one note that’s because it is. It may succeed in thematic focus—that’s for damn sure—but it forgets to rope in the magical qualities of its inspirations, to balance the bitter with the sweet.

The only area where I Am Setsuna succeeds wholeheartedly is how it plays. I never grew tired of its quick-paced combat, or its Spritnite-accumulating system. While I never really ventured outside of a very specific trio of heroes (Nidr, Endir, and Setsuna), the game still encouraged me to test out new parties to see who best complemented one another. Yet, once I found my favorite trio, I stuck with them for the rest of the game—there was never a need to deviate. Still, at its core, I Am Setsuna plays precisely like a classic JRPG of the Active Time Battle variety, and requires smart, spur-of-the-moment strategy as those games once did.

If I Am Setsuna were released in the 1990s, my mom might have played it. I’d sit idly beside her, wrapped in a flurry of blankets, next to my napping cat. It’s likely that we’d both somewhat enjoy it, but maybe would remark about how none of the characters stuck with us, or how the environments never amounted to anything you’d want to put on a postcard. I wish I Am Setsuna took me on another beautiful, multifaceted adventure like it wanted to, as the JRPGs that its creators admire once did. I wish the characters weren’t bland caricatures of familiar characters I’ve seen in the past. Instead, it feels like a cold attempt at harboring nostalgia, only managing to remind me of JRPGs of the golden age, and how so much better they were—and, critically, still are. At the very least, maybe I’ll finally give Chrono Trigger a try.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post I Am Setsuna is cold at heart appeared first on Kill Screen.

August 9, 2016

Creating voice-driven interactive fiction just got a lot easier

Interactive fiction has seen a resurgence in the past few years. From Chris Klimas’s freeware hypertext software Twine, to the visual novel Python engine Ren’Py, branching narrative stories are more popular than ever in videogames. But most interactive fiction games rely on written text, usually through hyperlinking passages or narrative decisions. These stories tend to stay in the digital world, rarely calling on the player to interact with the game outside of using their mouse and keyboard.

Amazon’s new program, the Interactive Adventure Game Tool, allows writers and developers around the world to create interactive fiction stories that rely on voice recognition. Created for game development on the company’s Amazon Echo (a hands-free speaker you control with your voice)—also known as Alexa—the Interactive Adventure Game Tool was developed in Node.js by Amazon Advertising team engineer Thomas Yuill. Yuill’s tool lets users write branching narrative structures that can later be published online to be played by Alexa users throughout the globe.

Amazon’s Alexa provides an all new medium for game design

Of course, adventure games have already been released as skills, or Alexa apps, for Amazon Echo owners. Just take a look at The Wayne Investigation skill, an adventure story released earlier this year in order to promote the Batman vs. Superman movie. The game puts the player in the role of a Gotham City detective investigating the death of Bruce Wayne’s parents. During pivotal moments in the story, the game provides the player the option to use their voice to choose the direction of the Wayne murders investigation—for better or worse. While the game is largely intended to be a tie-in story, it demonstrates the branching narrative abilities creators can use while creating stories for the Echo. Just check out Twitch streamer ksizzle’s live playthrough of The Wayne Investigation over on his official YouTube channel to get a better idea of the skill in action.

But the Interactive Adventure Game Tool doesn’t just let commercial developers create projects to promote their work. With the application uploaded onto GitHub, virtually any Alexa user can get started on creating their own stories for the Amazon Echo through the Tool. Not to mention, Amazon provides the Trivia and Decision Tree skill templates online to get started, in the hopes that newcomers can learn how to build their own games through the site’s official skills. While not necessarily the most approachable suite in interactive fiction development, Amazon certainly offers a hand to writers and storytellers interested in giving the program a try.

What’s truly fascinating about the Interactive Adventure Game Tool, though, is how Amazon’s Alexa provides an all new medium for game design. With virtual reality already on the rise this year, audio input provides another outlet for game makers to bring multimedia worlds into our everyday life. Granted, only time will tell if the Interactive Adventure Game Tool proves to be an inspiration for interactive fiction writers. But, if Twine and Ren’Py are any indication, digital storytellers are quick to experiment with new tools once they’re released. Hopefully, Amazon’s program isn’t the exception to that rule.

You can find out more about Amazon’s Interactive Adventure Game Tool right here.

The post Creating voice-driven interactive fiction just got a lot easier appeared first on Kill Screen.

Slayaway Camp turns VHS horror into a cute, murderous puzzle

Slayaway Camp is a puzzle game about massacring hapless teenagers, and, perhaps fittingly, it comes from a place of aggression. “After a decade [of] making gems go clink and pegs go… Peggle at PopCap,” said Jason Kapalka, one of the founders of PopCap, and now returning to independence with Blue Wizard, “I had a lot of pent-up aggression and wanted to work on something really violent and gross.”

A sliding puzzle game isn’t the most likely candidate to vent such vicious desires. And that’s entirely the point—Kapalka is looking to assault the sparkly, saccharine game genre with Slayaway Camp in action. As such, it will has you trot your skull-faced killer around the place laying the smackdown on unsuspecting victims. Move in a direction and you’ll keep moving until you hit an object, whether that’s a wall, a fire, or someone you want to headbutt to death.

“Sokoban-with-decapitations”

All of this isn’t coming out of nowhere. Kapalka says he’s a long-time horror fan and so he drew on this when deciding on what theme the original Slayaway Camp prototype should have—originally, it had a “generic Star Trek sci-fi feel.” It turned out to be a great opportunity to pay homage to the VHS-era of slashers. “One day we just thought, hey, what if these aliens or blobs you’re supposed to be eliminating were actually teenagers, and you were a psycho killer out of a horror film?” said Kapalka. “Everybody can get behind the idea of killing annoying teenagers.”

There’s been a run of 80s nostalgia in pop culture recently—Kapalka names the sci-fi TV series Stranger Things as the most obvious right now—but having started work on Slayaway Camp a year ago, it was never meant as a way to bank on this popularity. “Of course, I don’t think anyone has really gone for a Sokoban-with-decapitations approach yet,” Kapalka said. The game definitely has parallels in how it plays to many of Draknek’s puzzlescript titles, particularly Sokobond (2014), but it’s overlaid with the inspiration from classic horror tropes – fire, swat teams, and even cats (which you can’t kill as it’ll cause the movie to be shut down for harming animals) will be some of the obstacles you need to get around.

That approach should be what makes Slayaway Camp stand out. It’s not going for the glowing neon vein of 80s nostalgia as seen in Stranger Things‘s title sequence, nor is it on part with the grindhouse seediness of Power Drill Massacre. Instead, Slayaway Camp sits somewhere in between: it’s blocky and voxelated, meaning Blue Wizard can render its gruesome subject matter in a more friendly light—a game you wouldn’t be afraid to play on a train. It’s a cloyingly cute murder puzzle. Friday the 13th (1980) remade in pleasing voxels.

Slayaway Camp is coming to Kongregate later this month, before launching on Steam and mobile devices soon afterwards. Keep an eye on it over at its website.

The post Slayaway Camp turns VHS horror into a cute, murderous puzzle appeared first on Kill Screen.

@StayWokeBot helps you contribute and keep up with online activism

At first glance, civil rights activist DeRay Mckesson’s choice to collaborate in the creation of a Twitter bot seems like a strange move. After all, his 536,000 Twitter followers aren’t going anywhere, and bots lack the personal touch and capacity for individual engagement that’s made Mckesson’s Twitter such a cornerstone of his online community. But look a little further into it, and the bot—created by Portland technology studio Feel Train in conjunction with Mckesson and other Black Lives Matter activists—situates itself cleanly with the push for awareness and engagement in modern-day activism, both online and in the streets.

the human effort behind the digital is easy to overlook

The day-to-day grind of activism is exhausting. Like all good work, it requires tenacity and stubbornness, a desire to create something worthwhile out of something discouraging and the implicit responsibility to engage and connect with a community that may range from doubtful but open-minded to openly hostile. In the age of Twitter activism, where many of us receive our news in bursts that take mere seconds to type, the human effort behind the digital is easy to overlook. Mckesson has been out on the streets since day one—he was recently arrested in Baton Rouge after the shooting of Alton Sterling—but to many, he remains a dude in a blue vest that runs a Twitter account. And as vital as Twitter is to getting the message out, as well as keeping collaborators in contact with each other, the potential for both trolling and well-meaning but over-asked questions means that, after a while, it gets old.

Along with news and personal updates, Mckesson takes advantage of Twitter’s ever-presence in our lives to establish routine, a bastion of familiarity amid the hustle and drain of a fickle news cycle and the hostility he and his fellow activists are consistently exposed to. Every night, as the American Twitter scene winds down and Baltimore gets dark, he says,

Sleep well, y'all. Remember to dream.

— deray mckesson (@deray) August 7, 2016

It’s not a call to action or a political statement. It doesn’t need to be. At the end of the day, it’s little efforts like this that give the bigger issues context. And it’s that sentiment that Mckesson and Feel Train are trying to promote with @staywokebot.

If you tweet the bot and have location turned on it replies with the names and phone numbers of the senators that represent you, giving you an instant clue as to how you can lend a hand. But @staywokebot isn’t just a finger pointing at what it wants you to do. To label it such does a disservice to the personality and charm Mckesson and co. have imbued it with, and ignores the solidarity and community encouragement this movement has worked so hard to cultivate. Every time someone new follows the bot, it @-replies them with a message of empowerment that centers a Black artist, leader, or activist. In the midst of pushing people who may only engage with the movement on Twitter to pick up the phone and make a concrete change, @staywokebot affirms the humanity of every single person that engages with it. An ambitious task for a bot, but one it does well.

Black Lives Matter organizer Samuel Sinyangwe, who helped create the bot, says that he wants it to be “like a friend.” The familiarity is intentional; it’s the logical expansion of Mckesson’s nightly tweets and a movement that’s tried so hard to engage on a personal level, not just through media. “It wants to help you become a more empowered activist,” Sinyangwe says. “You feel comfortable with it.”

H/t Fastcompany : Check out @staywokebot on Twitter

The post @StayWokeBot helps you contribute and keep up with online activism appeared first on Kill Screen.

How to understand No Man’s Sky

No Man’s Sky is out. You’ll have to forgive me, but that feels like something worth saying. Not because the game is the second coming, or because it is “the last game” we’ll ever need, but because, even after all this time, it remains a game built in service of a tantalizing idea.

When Sean Murray spoke to Kill Screen’s Jamin Warren earlier this year he put it simply: “the emotion that we wanted to get from people is that emotion of, ‘I have travelled to a place and discovered it.’” That idea, of true discovery in a digital world, has perhaps been lost of late. Discussions of length and breadth, features and bugs, delays and disappointments has obscured its simplicity. The weeks leading up to release have been shadowed by complications, diversions, and unnecessary details. Yet, No Man’s Sky, from my first impressions, doesn’t seem overtly concerned with those details. Instead, it feels confident, broadly drawn, and surprisingly human. Its systems are robust, toylike, and eager to please. Its creatures are goofy, its starships look kitbashed and its landscapes can be eye-searingly lurid.

is it the poster child for new procedural generation

Yet, the sum of the controversies, misunderstanding, and expectations of many still seem to weigh on its release. The question that lies beneath this nervous rumble is “which No Man’s Sky is the real one?” Is it the programmers’ dream game, the one that delivered Sean Murray’s nervous excitement to the center stage of E3, bringing with it explanations of maths and perlin noise that rarely make it out of the studio doors? Or is it the poster child for new procedural generation, a reinvigoration of a technique older than games themselves, pointing towards a bright future? Perhaps it is the ultimate space simulator, an infinite universe richly populated with systems and features, drawn with Nintendo-like luster. Or maybe it is the infinite game itself, the one with untold combinations of limitless variables, the one that might eclipse reality entirely.

When you begin to list these expectations, variations, and partly fabricated visions of No Man’s Sky you begin to hone in on the problem. Perhaps uniquely, No Man’s Sky has found itself to be a canvas for the projections of those eager for games to deliver their childhood fantasies to them wholesale. This seems to be a trait of its assigned genre, the “space sim,” which places it among the company of Elite (1984), Freelancer (2003), EVE Online (2003), and Star Citizen. It’s a genre that, perhaps because of the presence of “simulator” in the title, seems disengaged from ideas of artistic and personal expression, presenting instead the imaginary ideal of a “total” universe, sured up by a rhetoric of “infinite possibilities” and “go anywhere, do anything” ambitions. It’s a genre that, in some strange way, has its own teleology, a final destination of a complete simulation of existence, a collectively imagined fantasy of a complete digital universe. This fallacy has both guaranteed No Man’s Sky a healthy following of insatiable fans, and obscured its actual nature as a game. The ubiquitous cries of, “but what do you do?” have originated from a willful misunderstanding of the game, a disbelief that the focus of a supposed “space sim” would be the wandering exploration of planets in service of a sense of wonder alone. It was as if people found it impossible to believe that an “infinite” game would be created without bowing to their genre checklists and outrageous expectations.

In reality, No Man’s Sky is what it appears to be: An impossibly big game, created by a small, passionate team. A personal exploration of ideas of wonder and discovery. A love letter to the optimism and imagination of 1970s science fiction. When Warren spoke to Murray earlier in the year, they didn’t speak about grand visions of infinite simulations, or whether the game had black holes, binary systems, and planetary rings. They spoke about immigration, travel, and vast unknowable landscapes. They talked about Murray growing up in the Australian outback, a place he remembers for “massive wide-open spaces, being completely alone basically, and crazy skies as well.” He added: “My parents claim full ownership of No Man’s Sky.”

“if you could evoke the true emotion of exploration”

They discussed how Murray visited the North Pole, and after his Ski-doo broke down, ended up on his own, hours behind his expedition: “I should have been stressed, I should have been worried. But I was just like, ‘This is amazing.’ I had no idea how to get back. I was maybe going the wrong way. But let me just take this in.” Ultimately, they spoke about the things Murray and his team at Hello Games would have spoken about when they first started on the journey of making No Man’s Sky: “What we talked about was imagine Skyrim [2011] or Red Dead Redemption [2010], leaving the cities and the scripted part of the game behind, going out.” Explains Murray, “the core of that really exciting idea, which is if you could evoke the true emotion of exploration—that’s a really inherently human thing.”

Inherently human. It’s perhaps not the image people have of the impossible alien expanses of No Man’s Sky, of its sense of untold promise. Yet, on the day of its release, that is what we are entering into. Not an infinite universe, not the ultimate space sim, but something human. Yes, No Man’s Sky will be judged on genre, it will be judged on the features people think it should have, and it will be almost certainly be found wanting by some, falling short of their imaginary “perfect game.” But, if it is to be valued, it should also be judged on its own terms, measured up to its own ambitions. It should be understood as a piece of personal expression, a filtering of life experience, and a ridiculous and specific dream made into something flawed, complex and real. Otherwise we stand to miss why this most unlikely of games exists at all.

The post How to understand No Man’s Sky appeared first on Kill Screen.

A videogame tribute to one of the best worst movies of all time

What happens when Johnny goes to work? What happens when he buys the red dress or makes love to his fiancée Lisa? If you’ve ever wanted to know, there is an answer: The Room (2003), the best worst movie of all time, now has an adventure game adaptation.

A 2D adventure game, The Room Tribute “is a totally unofficial game made simply out of [an] undying love of the movie.” It follows the course of the movie through the world of Johnny—The Room’s main character, a bank employee who is having problems with the people in his life that he should be able to trust, but are acting in ways that don’t benefit him. If this seems like a strange premise for a game, it’s a pretty strange premise for a movie as well.

achieved cult-like status for its alien strangeness

The Room is considered one of the worst movies of all time, a creation of actor/director/producer/writer Tommy Wiseau. For those uninitiated into the world of “so bad it’s good,” the more titles you can add to your creator’s name the worse of a sign that is for the quality of the film, the talent stretched thin across so many roles. It falls into that same pantheon of the great bad movies—Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959), Troll 2 (1990), and Miami Connection (1987)—has achieved cult-like status for its alien strangeness. But there’s a specific quality to The Room that makes it fodder for tribute, at least in the mind of one of the project’s designers Tom Fulp: “The Room is the most pure of the ‘so bad its good’ movies and it has the most heart. A lot of the other ‘bad’ movies feel like they’re intentionally hamming it up and playing to the fans of the genre, whereas The Room feels like it honestly is just trying to be a good movie.”

For their videogame tribute, the game’s creators chose to follow the character of Johnny—the game is told through his perspective, and you only see the scenes from the movie that he was present for. The film follows multiple perspectives, from a rooftop drug deal with Denny, to Lisa cheating on Johnny with his best friend. The game only follows Johnny: “The film mostly revolves around Johnny so it made sense to make him the playable character,” said the game’s creators. “It was a fun exercise to capture the story of the film while always keeping the player in the role of Johnny.”

By doing this, they manage to create a much more sympathetic character than if they had just recreated the situations that take place on screen during the film. In writing Johnny, Wiseau has crafted himself into the ultimate Mary Sue character—a good guy who is great to all his friends who everyone likes, but who is just perpetually screwed over by bad people (women). He’s a character without flaws, a characteristic that makes him difficult to relate to. While it wasn’t the original intention of the game, Fulp and his fellow game makers manage to make Johnny somehow sympathetic: “When you watch the film you can detach yourself from Johnny but the game forces you to BECOME Johnny and experience the events of the film through his eyes.”

You can play the Room Tribute on Newgrounds.

The post A videogame tribute to one of the best worst movies of all time appeared first on Kill Screen.

A wooden book filled with puzzles is the coolest new toy

The Codex Silenda is a set of intricate wooden puzzles that quickly reached its funding goal on Kickstarter many times over. It’s the kind of object you’d expect to be hand-carved by a slightly eccentric artisan, but it’s laser-cut, and one of the reward tiers gets you the pieces, which you would then assemble into the puzzle yourself. As it turns out, the laser-cutter can do for the mechanical wooden toy what the printing press did for books.

There were books before the printing press: painstakingly hand-copied manuscripts with margins full of knights jousting snails, but hand-written and hand-bound books represented a huge investment of time and money, not just for the book itself, but for the expertise necessary. The press itself is often credited with bringing about a new age of education and literacy—books were suddenly significantly cheaper to produce, and therefore more common and easier to move from place to place.

Expertly hand-carved wooden objects have a long history—the cuckoo clock is an icon of German engineering and craftsmanship, and multi-step Japanese puzzle boxes are more about the experience the box provides than whatever object is hidden inside it. The Codex Silenda and all its moving pieces call back to these forms, but it is not worked over by a woodcarver making one at a time and selling them as luxury items, it’s made by a designer with the help of a laser-cutting tool, and they’ve already sold all 600 of them. At a different reward tier, they’re offering the laser files—the Codex can belong to anyone with $80, a bunch of wood, and access to a laser-cutter.

made up of beautiful wheels, gears, and irises

The Codex has five pages, each with a different puzzle that must be solved in order to open up the next one. It is made up of beautiful wheels, gears, and irises, and covered in laser-cut runes. The book also has a story in it, about an apprentice in Leonardo DaVinci’s lab who’s trying to solve the puzzles as quickly as possible. Like the Rubik’s Cube, The Codex seems to be a challenging and visually arresting puzzle, but it’s more pleasant to hold and more attractive to display than plastic and stickers. It is at once an update of an old style of wooden puzzle and a new kind of toy, available only through the help of modern machinery.

You can find out more about The Codex Silenda on its Kickstarter page.

The post A wooden book filled with puzzles is the coolest new toy appeared first on Kill Screen.

The new mundanity of space games

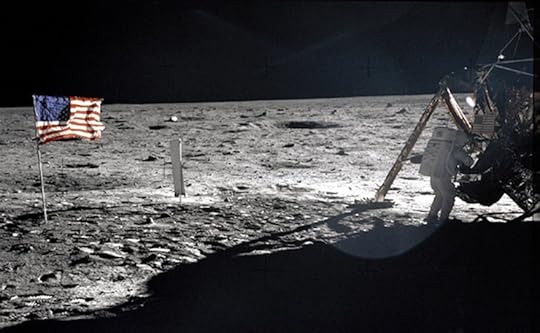

The conference floor was full of astronauts, engineers, and students. Bodies quickly filed past each other to find an open seat. My team of 4th graders waited impatiently to sit. Before I could join my fellow classmates, a hand reached out to guide me to a new seat, away from the others. Instead of sitting a few rows back, I was ushered toward the front. Next to me was John Glenn. Former astronaut. The first American to orbit the Earth. Fifth man to travel to space. I stared up at him in awe. He’s been to outer space. I want to go there too. He noticed me and smiled. The lights dimmed and a presentation about the Mars Rover began to play. Space Day 2004 had approached lift off.

///

NASA’s Space Day is an educational initiative designed to encourage students to pursue careers in STEM. I was 10 years old when my teacher Ms. Voigt announced the competition to the class, and through her encouragement seven students, including myself, decided to enter. There were several different categories to choose from, but we decided on the Space Trek challenge. The prompt was to keep a fictional log detailing our day-to-day lives on the moon. More specifically, how we fared inside the crater Copernicus. Our team was named the Crescent Craters.

We documented our progress on a website we made with the help of our teacher, and described everything from the surface temperature to how fast the lunar rover vehicle (“moon buggy”) traveled that day. We drew comparisons between exploration of the moon to Robert Peary and the North Pole. We tracked the phases of the moon and recorded our findings. Because we were allowed creative freedom, we mapped out the logistics of creating a retreat on the moon for Earthlings. I took things one step further and convinced my dad to buy me a telescope. We went to the local planetarium so that I could see all of the constellations and learn their names. I would clip out newspaper articles announcing the date and time of asteroid showers and beg my parents to let me stay up late enough so that I could watch.

If I couldn’t physically go to space myself, then doing it virtually was the next best thing

One day, Ms. Voigt asked my team and I to stay behind for a of couple minutes after the bell rang. She told us excitedly that we had won the Space Day challenge. The following weeks were a blur. Our small town was proud that a group of local kids accomplished something that would garner the attention of larger communities. The newspaper wrote a few pieces about the winning teams and took photos of all of us. I still have copies hidden away in a box, given to me by delighted family members who supported my dream. Space Day was a big part of my identity at that time.

When I started 5th grade the following year, it became apparent that my academic weaknesses would squash the expectations I had for a career in space. While my level of reading and writing surpassed those around me, I was tutored after school in math because it was my weakest subject. I loved science, but the older I got, the more its concepts flew over my head. Middle school had students take standardized tests that would give them an idea of what their career path would be. My results told me I’d be a firefighter. Disheartened and lost, I stumbled into high school, abandoning the idea of leaving this planet through means of rocket propulsion, and spent my formative years drifting without a purpose.

///

The idea of human space exploration is enticing even to those of us without the necessary skills required to become an astronaut. Science fiction has given me a romanticized insight on our universe and my place within it. I’m fully convinced that there are other forms of intelligent life (aliens) that share the galaxy with us. Although science fiction has no grounds in reality, it still fosters the curiosity and excitement that my dad felt as he watched the moon landing from his television in 1969. That said, technology is increasingly in a position to turns dreams into reality. Nowadays, society’s dream of going to outer space is being achieved in a variety of ways—thanks to the easy accessibility of the internet and emergent technologies.

Videogames are, of course, one of the more popular conduits for achieving this goal. It should come as no surprise, then, that during my time of uncertainty in life, I discovered the Mass Effect series. It was then that my fascination with games that allowed me to be among the stars manifested. If I couldn’t physically go to space myself, then doing it virtually was the next best thing. What particularly grabbed me about the first Mass Effect (2007) game wasn’t the interactions I had with companions or the futuristic combat and advanced technology. I loved and consequently paid high attention to the spacecraft, interfaces like the galaxy map, and the engrossing world of its space politics. These details provided the kind of ordinariness—a sense of daily life—in outer space that made sense to me.

The SSV Normandy was a big part of the game’s success for me. Significantly, it’s a vehicle crafted by a collaboration between humans and aliens, and houses your entire crew. The presence of the crew being everyday people, unlike the battle-ready soldiers that star in the game, appealed to me. They maintain system operations and talk with each other. Being able to walk about the cabin and examine the quarters and the dining hall made the experience feel more plausible. Using the galaxy map to leave the Normandy and explore surrounding planets feels bare, as most of the new worlds look the same visually. But it offers the opportunity to put a helmet on and rely solely on an oxygen tank. Through Commander Shepard, you’re able to set foot on Earth’s moon. You can glance up at the darkness and take it all in—your home planet staring back. But, for me, this is where the illusion ends, because as you walk on Mass Effect’s facsimile of the moon, dust isn’t kicked up at your heels. Neither do you bounce around in the low gravity. Footsteps don’t leave imprints. I was taken out of the experience, only to realize that this made me want a better representation of space travel.

Naturally, I have taken to seeing what other means including other videogames are available to bring people closer to the mundanity of space. If you stick with videogames, there are potential options such as The Fullbright Company’s Tacoma, which will take place on a space station and feature zero gravity movement. Instead of interacting with aliens, you’ll be left to piece together information about the previous crew members who once lived on board. In avoiding the wilder temptations of sci-fi, Tacoma looks to depict a reality that could plausibly occur in our future, one that looks to the ghosts of technology that we leave behind today. Adr1ft by Three One Zero (also available in VR) is another interesting approach that tasks you with exploring the wreckage of a destroyed space station, but you do this while fighting for survival as your EVA suit leaks oxygen. It’s an effort that brings to the fore the unforgiving nature of space; the fact that we are not built to survive its vacuum.

society’s dream of going to outer space is being achieved in a variety of ways

You’re left to float helplessly among the wreckage, taking in the severity of the situation while also gazing upon the Earth looming in the background. It encapsulates the fragility and beauty of spacewalking that we can only read about in the written memories of astronauts. Perhaps, with the addition of VR, you can actually get the feeling that you’re floating. But why stop there when private companies like The Zero Gravity Corporation exist? Using a specially modified Boeing 727, the company can fly you high up and then let the shuttle freefall to achieve a momentary weightless environment, allowing you to float as if you were in space. If you’ve got the funds for it ($250,000) there’s also Virgin Galactic, a spaceflight company that is developing commercial spacecrafts to provide sub-orbital spaceflight for “space tourists.”

No Man’s Sky should be unprecedented in its ability to let us ordinary folk explore space and discover new planets. And while this is epic in every way, what stands out the most about the game is how routine it aims to make the experience. You fly from planet to planet, charting their lands, their creatures, and pretty much everything else you see. It’s a game that turns you into an intergalactic scientist who, unlike those in Mass Effect, charges in with a clipboard rather than a gun. You become like one of the many people staring up at the night sky through their telescopes, acquiring a wealth of knowledge about the unreachable, except in No Man’s Sky your faraway subjects are reachable. Expect screenshots from the game to emerge like the photos on this website, which contains pictures taken by the Hubble telescope. There are different albums that feature everything from galaxies and their sub-categories to nebulae. Each album contains pages upon pages of what is naked to the human eye. The shots are breathtaking.

No Man’s Sky also makes an effort to leave in every detail in its simulation of space travel. You’ll be sat in the cockpit with a full view of your ship’s interior. As you fly into a planet’s atmosphere and look from the window, you’ll be able to see the clouds breaking apart, and watch as bits of rubble fly past your view. Its greatest hit might be that it’ll provide seamless transition from orbit to landing—not a loading screen in sight to take you out of it. Modifications and upgrades can be made to your ship too, allowing you to act as a fighter, a trader, or to preference stealth, speed, and interstellar exploration. Kerbal Space Program (2015) has already taking this engineering fantasy further as it tasks you with creating a vessel that can guide your team to new worlds. When constructing a space craft, each piece must be assembled carefully—each part has a different function, which could impact the way a ship flies or fails. Appropriate physics ensures that if you design a bad ship, it will crash. If successful, you can navigate to distant moons, asteroids, or planets. Despite your crew consisting of members of a tiny green species known as Kerbals, the customization and freedom to build and explore space on your own terms is freeing. NASA feeds that same fascination through software that is open source and featured on GitHub, allowing those who are interested in the technical aspect of space to see what programs are used for what and how. Then there’s the Mars One initiative, which is a not-for-profit foundation with the goal of establishing a permanent residence on Mars. But perhaps more interesting than that to wannabe astronauts like myself is that Mars One will recruit ordinary people to become a Mars One astronaut, provided that they make it through a selection process of four rounds.

To go one step further and really emulate being in the shoes of an astronaut there’s Lunar Flight (2012). It’s a lunar landing simulation that has you transporting cargo and acquiring data at survey locations. To add tension, there’s limited fuel in the lunar module which provides a sense of urgency to your carefully calculated actions. It recreates the kind of anxiety one might get from watching the Mars Rover landings. Will it be a success or a failure? Which then becomes: am I a competent astronaut? It’s the question I’ve avoided the answer to for years now, perhaps hoping to find it through these space travel surrogates—as if I could ready myself for the job of an astronaut by artificial means.

///

I walked through the crowd of engineers and astronauts at NASA’s Space Day with goodie bag in tow, weaving through all of the space-related stations on the event floor. There was even a machine similar to an aerotrim that kids could be strapped to in order to experience a more forgiving, less vomit-inducing look into astronaut training. There were models of previous rovers and space shuttles to look at. I ate freeze dried ice cream from a silver bag. But more importantly, I got to speak with someone who was going to be sent into space. Soon. I don’t remember much, but he was tall and answered all of my childish questions with a smile. He signed the back of my t-shirt along with his fellow graduates. The shirt is safely tucked away in a box in my closet. It’s the closest to space I got.

The post The new mundanity of space games appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers