Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 54

September 20, 2016

The new Blair Witch deserves to be left in a corner to die

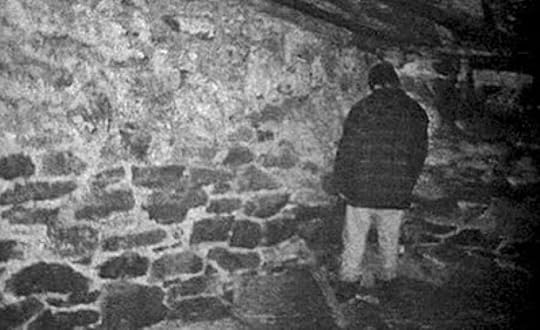

The Blair Witch is back, and—this time—she’s coming for your drones. That pretty much sums up the new Blair Witch sequel from series-fresh director Adam Wingard and writer Simon Barrett. It wears the skin of the witch we know and love from the seminal 1999 found-footage film, from creepy twine stick figures to stone cairns. But set in 2014, and targeted at a 2016 millennial audience, it features YouTube videos rather than VHS tapes, high-waisted pants rather than grunge sweaters, and GoPros rather than grainy night vision.

I wanted—no, I tried—to like Blair Witch. To me, the backlash over the original’s morally questionable marketing tactics (and culpability for things like the Paranormal Activity machine) doesn’t diminish its contribution to the horror genre. At the end of the day, whether you love or hate The Blair Witch Project as a phenomenon, it was nothing more than a good old ghost story. Maybe even a great one. Creating an intangible, yet pervasive and palpable force of a boogie(wo)man, it delivered what all horror audiences crave: a myth to fear.

it delivered what all horror audiences crave: a myth to fear

The marketing that sold the improvisational found footage style as legitimate only heightened the film’s best quality, which was that voyeuristic sense of watching something you shouldn’t be. And, having been created by amateur filmmakers exploring an untapped storytelling idea with a $60,000 budget, The Blair Witch Project really was a movie that, by Hollywood standards, should never have seen the light of day. But, boy, did it ever. It saw so much light that it practically broke Hollywood.

With a $5 million budget—not to mention dialogue and actors so focus-tested that you’re pretty sure Lionsgate crafted them in cryogenic tanks—Blair Witch fundamentally lacks that sense of the forbidden. It’s a classic Hollywood-has-no-idea-what-human-people-are-like move. Almost 20 years ago, a cult following sprung up around a low-budget indie horror flick that only worked because it was devoid of what made Hollywood horror so predictable: CGI, glossiness, and jump scares. In response, Hollywood has remixed it into a branded, multimillion dollar funhouse filled with CGI, glossiness, and jump scares. Save your sarcastic applause.

Aside from the stink of too much money, Blair Witch also stinks of executives vying for millennial attention with a hodgepodge of internet culture. The story begins with James, the brother of a victim from the original movie (Heather), watching a newly uploaded YouTube video that leads him to believe his sister might still be alive. Seemingly bankrolled by Lionsgate itself, the new “amateur filmmaker” capturing James’s ill-fated search comes replete with earpiece cameras, GPS, and drone functionality (to help them navigate the woods in case they get lost *wink* *wink* *wink* *wink*). Later, when shit hits the fan in Black Hills forest, we see glimpses of the witch herself, effectively destroying her intangible pervasiveness from the original just so you can catch a few shots of a long-limbed, Slender Man-esque figure.

People like to look down on The Blair Witch Project and found footage films for relying on “cheap tricks” like shaky cams. But the need to be economical with both budget and visual effects, often leads found footage’s monsters to be closer to the myths and legends of the past: those archetypal fears with vague but familiar shapes. More often than not, they are witches, demons, ghosts; monsters best left up to the imagination, and who we’ve been imagining since human beings told their first stories. The monsters of found footage film, in most cases, should be left unseen, and instead felt through their absence and unknowability (with the incredible grotesqueries of 2007’s REC serving as the exception to the rule.)

she becomes some old, Dobby-looking lady shifting around trees

The original Paranormal Activity understood this, and had its terrors lift bed sheets invisibly, and drag humans down hallways by their feet in absolute silence. The monsters of found footage films leave wooden stick figures behind as you sleep and keep your friends motionless in the corner of a room while they murder you. By giving the Blair Witch a (stupid, uninventive, almost comedic) form, the new filmmakers not only made her look less frightening, they also gave her the boundaries of a corporeal body. Instead of an omnipresent force, she becomes some old, Dobby-looking lady shifting around trees, trying to regain some of her power by scampering out of view.

The Blair Witch Project catapulted into a phenomenon because of the things it didn’t tell us. It didn’t tell us why the Blair Witch kept her victims in corners, it just left you to realize that every corner in the final house was covered in the tiny bloody handprints of children. It didn’t even tell its actors to act scared, it just left them to camp for seven days in the woods, giving them fewer and fewer food rations in between, only to terrorize them throughout the night. Hell, it was a movie that, conveniently, didn’t even tell the audience it was fictional (which, again, a questionable tactic, but undeniably effective). The Blair Witch Project told its story with so much restraint that some fans became obsessed with finding clues and easter eggs that weren’t even there. It did the job of any good scary story: it made you see ghosts everywhere.

Don’t get me wrong, there are a few choice moments and qualities that show the stifled potential of Blair Witch‘s director and screenwriter, who proved their proficiency for intelligent, well-executed horror camp with The Guest (2014) and You’re Next (2013). But you’ll notice that I spent very little time actually describing Blair Witch’s plot. That’s because I searched far and wide and found nothing to report. So many threads begin only to peter out to the sound of a single tree falling in the woods with no one around to hear it. Early on, a character gets infected by an Alien-looking parasite swimming under her skin like a gully fish—only to unceremoniously be ripped out of her leg with little fanfare or consequence half an hour later. The drone which, at first seems to promise the advent of aerial shots showcasing the witch’s terror, quickly gets stuck inside a tree before it can do anything but annoy you for existing. All in all, I can’t say I left Blair Witch knowing what the hell filled up those 90 minutes apart from gratuitously unearned jump scares and the torture of six very good looking youths.

Ignoring just about everything that made the original an irritatingly irresistible hit, Blair Witch blundered into the world’s mythology with the subtlety of a sledge hammer—or rather, the sound of a drone angrily tearing through a forest.

The post The new Blair Witch deserves to be left in a corner to die appeared first on Kill Screen.

Dusk is how you make a ’90s shooter for today

Living in the Northeast of the United States, David Szymanski grew up surrounded by the eerie woods and old buildings that dot the landscape in that part of the country. This is an area of the U.S. where you can find what Lovecraftian scholar S.T. Joshi calls “The Miskatonic Region,” the setting for many of the author’s strange and disturbing stories.

Since the age of 14, Szymanski has wanted to create a first person shooter set in this part of the U.S. Now 26, he is finally making that dream a reality with Dusk.

“I’ve always been a huge fan of Doom/Quake-style FPSs, since I was a young teenager,” Szymanski said. The idea for Dusk has been in his head ever since. In 2013 Szymanski created Pit, a game he described as “flawed.” It was his first attempt at making a fast-paced 90s-style shooter. After finishing Pit, Szymanski began creating narrative-driven psychological horror games. A Wolf In Autumn (2015) was his latest.

But after finishing Wolf, he felt “burned out” on those types of games and making games in general. “So I decided to take some time off,” Szymanski explained. “That is, spend time programming for fun rather than immediately jumping into a new serious project.” After starting and stopping work on a few ideas, Szymanski decided to model a low-poly shotgun and attached it to a camera in Unity. He wanted to see how much he could make it look like Quake (1996). “And things kind of took off from there,” he said.

So much of Dusk comes from the ideas of 14-year-old Szymanski. And this is by design. Even the name of the game, Dusk, is an idea from the young mind of Szymanski. At 14, it was a name that sounded moody and cool. And he figured “What was good enough for a Doom-obsessed 14-year-old was good enough for a Doom-obsessed 26-year-old.”

“EVIL MAGIC and INDUSTRIAL WASTE HAVE BEEN FERMENTING TOGETHER”

The area where Szymanski grew up is also influencing the story of Dusk. 90s shooters weren’t known for their sweeping or epic narratives and Dusk, too, won’t have much in the way of storytelling. Still, it will have a semblance of a narrative, which Szymanski explained: “A huge network of Lovecraftian ruins are discovered underneath a section of rural farmland, and the government decides the best way to deal with it is to build a bunch of research facilities and factories to harness whatever magic they find. Eventually a combination of possession and industrial accidents forces them out and the whole area is sealed off.”

The player in Dusk is a down-on-their-luck treasure hunter who hears rumors of ancient gold hidden deep within the sealed area. “So they’re entering a place where evil magic and industrial waste have been fermenting together for years, with all sorts of weird possessed humans and weird creatures to deal with.”

Part of making Dusk resemble a high-speed shooter from the 90s are the visuals. Dusk looks like it was built in the Quake II (1997) engine but, in fact, it’s being built in Unity—a modern game engine capable of some truly impressive visuals. Which is a problem. “[The] biggest challenge is just convincing Unity to stop doing things that make the game look better,” Szymanski said. Through a process of trial and error he has figured out different ways to make Dusk look truly retro. This involved not just using lower res textures, but using textures that had a smaller color palette—a limiting factor for games back in the day. Some of these settings can be turned on and off, “depending on how faithfully crappy players want Dusk to look,” Szymanski said.

Also key to manufacturing a modern game so that feels like it fell straight out of the 90s is the feel. To this end, Szymanski is making sure to recapture the nonlinear, hand-built level design games like Quake had, and to include secrets and abstract architecture seen in the original Doom. But not everything from the past is being included in Dusk. “I want to avoid unintuitive navigation and overly obscure puzzles,” Szymanski said. Not everything transfers so well into the present day. By the looks of it, there’s also some wild new moves in Dusk, but ones that feel oddly at home in this style of shooter—you can be launched high into the air and end up falling upside down while blasting your guns at enemies.

A track called “Endless” created by Andrew Hulshult for Dusk

The final aspect of 90s shooters that Szymanski and I discussed is the hard-hitting and fast-paced music. To effectively replicate this in Dusk he needed help. So he called Andrew Hulshult, who has created the music for numerous games, most notably the gory fan mod Brutal Doom. “[Szymanski] sent me a quick build of Dusk to check out,” Hulshult explained, “I sat there with the game in a very unpolished and unfinished state and played it for an hour or two, if that tells you anything.” Hulshult was even more excited to work on the project once he discovered that Dusk was being created by one person. “Less filters to funnel ideas through,” he said.

“shooting for the same feeling I got when I fired up Quake”

The music and sound effects Hulshult is creating for Dusk range from eerie ambience to heavy industrial metal tracks. Like Szymanski, Hulshult is a huge fan of the old-school shooters and this influence is heard in the music he creates for Dusk. “I am shooting for the same feeling I got when I fired up Quake or Quake II for the first time,” Hulshult said. But he isn’t trying to imitate the music from those 90s shooters; he wants to make something that sounds original and his music won’t be restricted by 90s-era PC hardware either.

This strive towards something original on the back of nostalgia is what Szymanski is also aiming for with Dusk. Yes, it’s heavily inspired by games like Doom and Redneck Rampage (1997), but he wants it to have its own style and personality. For him, it’s not about recreating those games from his teenage years, but being faithful to them.

Dusk is coming out in 2017 for PC. Consoles versions are being considered. You can follow Dusk on Twitter. You can also follow Andrew Hulshult on Twitter.

The post Dusk is how you make a ’90s shooter for today appeared first on Kill Screen.

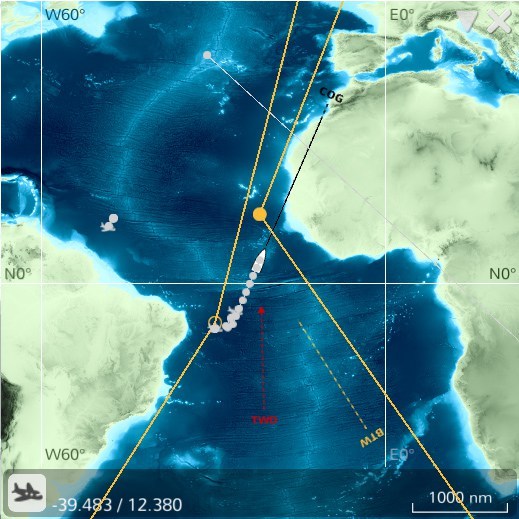

There’s an absurdly realistic game about sailing the world’s oceans on the way

The thrill of traveling the ocean has captured our attention for millennia, across cultures and continents. From the westward journeys toward a new world to the harrowing quests of circling the globe or reaching the poles, sailing these vast blue expanses has long been tied to adventure and discovery. Perhaps it’s that intrinsic link that makes the sailing in The Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker (2003), Salt (2014), Assassin’s Creed Black Flag (2013), and other games feel so satisfying and exciting, letting the layperson experience the freedom of the open ocean.

The upcoming Sailaway hopes to capture that freedom in its totality. Its ambition can’t be understated; the vision of creator Richard Knol is one of realistically-scaled oceans rocked by storms and weather influenced by real-world and real-time weather conditions. It’s also one of a simulated sailboat where the player must manage and control every major part of the vessel from trim line to outhaul. And one of sailing upon a sea where shallows and shores and currents and waves must all be considered and navigated. It’s a game about sailing, not merely a game with sailing.

“Of course there are quite a few sailing simulators available already,” states Knol as he discusses his rationale behind a sailing sim. “But most of them focus on regattas and don’t allow you to sail big journeys across the oceans. This is how the idea for Sailaway.world was formed. A realistic sailing simulator that allows you to travel across the oceans or even around the world.”

a storm in reality will result in a digital storm

Sailaway promises a scale where sailing across the Atlantic or Pacific will take hours and weeks, your ship continuing its journey even when you’re offline; navigating by nautical maps, you’ll be able to study the currents, depths, and most importantly the weather. Interestingly, Sailaway‘s weather is abstracted from NOAA data, so a storm in reality will result in a digital storm, and vice versa with high pressure areas and periods of calm.

Navigating both the calm and rough waters will require an understanding of your sailboat, learned through interactive tutorials and automated aids, or personal experience if you’ve sailed before. Sailaway represents all the major aspects of the boat, tasking you to “raise sails, pull the winches, set reefs, adjust the sheets, outhaul, downhaul, traveler, vang, backstay,” and other actions necessary to adjusting to the winds and currents. You’ll even be able to manage those parts away from a computer; Sailaway will be cross-platform, so course and sailtrim can be adjusted from the comfort of a tablet.

Sailaway is expected to release on PC, Mac, and Linux in November. For in-depth details on the sailboat controls and other mechanics, you can check out the game’s site.

[image error]

The post There’s an absurdly realistic game about sailing the world’s oceans on the way appeared first on Kill Screen.

Bjarke Ingels’s new game is everything good and bad about his architecture

Bjarke Ingels’s portfolio can now be viewed as an online game called Arkinoid, which is an updated version of the classic (and similarly-named) arcade game, Arkanoid (1986). Of course it can—it was only ever a matter of time. That is meant as a relatively value-neutral statement, but inevitably it can also serve as a sort of Rorschach test for how you feel about the Danish architect. The whole thing is at once playful, pointless, childlike, simplistic, amusing, and glib, and whatever combination of those things that you see in the game probably also applies to the Bajrke Ingels Group’s work.

All of which is fair enough. A game in which you bounce a ball off the icons for Ingels’ various projects configured in different layouts, which is all Arkinoid is, cannot be expected to contain deep rhetorical powers. But the whole site, amusing though it may well be, hints at the discursive limits of Ingels’s approach to architecture: Can all this surface cheerfulness really explain every project the increasingly omnipresent company takes on?

mirrors the discursive limits of Ingels’s cheery futurism

“Arkinoid brings back the good old nostalgia by reinterpreting the famous classic Arkanoid, BIG style!” the firm told Dezeen. “The BIG version lets you destroy our website icons,” it added. “The icons are reconfigured in different ways depending on the level, and each level gets more complex and harder to complete, kind of like architecture!”

This sort of rhetorical strategy is typical of BIG, a firm that has built models out of LEGO and has previously proposed building complexes that resembled roller coaster rides. The upside to this approach is that it can make architecture seem exciting and accessible, which other practitioners sometimes struggle with. The cold remove of Rem Koolhaas, for instance, is less likely to win over average members of the public. The problem with this approach, however, is hinted at in Mark Binelli’s recent Rolling Stone profile of the architect:

Ingels’ savvy communication skills, his ability to sell potentially transformative design concepts like he’s pitching a roomful of first-round investors on a new app that’s going to totally disrupt going to the dentist, has cut both ways when it comes to BIG’s reputation. “Bjarke is the undisputed king of the architectural one-liner,” says Oliver Wainwright, the architecture critic of The Guardian, “but it sometimes leaves you wanting more to chew on. Most architects will reach for much more profound metaphors. They’re reluctant, I think, to spell out their process in such a direct and transparent and, yeah, childish way.”

Looking back at Yes Is More, Ingels says, “I think we did ourselves a little bit of a disservice. I mean, it was actually quite well-received, but I think it made it a little bit easy for our critics to dismiss what we do as cartoonish, because literally we made a cartoon. But, you know, the haters will hate, right?”

If the comic came off as a bit goofy and unserious, Ingels’ own habit of behaving as if he’s auditioning for an architecture-themed show on Viceland has done little to help his cause. It wasn’t enough to name his company BIG; he revels in the fact that its Danish Web address is big.dk. “Who doesn’t like a big dick?” he asked over dinner in Las Vegas. “Men like it, women like it!”

Arkinoid embodies all of these tensions. It’s proudly childlike and unserious, but one is never entirely sure if that matters. Architects can be fun, too. It is not a particularly interesting game on its own merits—the Block Breaker formula is not meaningfully improved with BIG icons—but it provides a space for reflecting on BIG’s work.

The intentional emptiness in the game mirrors how I have come to feel about Ingel’s original tagline: “hedonistic sustainability.” The architect’s early projects cashed in on the idea that environmentally sustainable design needn’t be equated with sad, unhappy lives of scarcity and sacrifice. This, up to a point, is true. But what happens when real trade-offs have to take place, when the boundaries of “hedonistic sustainability” are exceeded? The lack of interesting choices in Arkinoid ultimately mirrors the discursive limits of Ingels’s cheery futurism.

This issue is also reflected in Leopold Lambert’s criticism of Ingels’s mega-block-like proposal for a New York City police station:

In February 2016, the New York City Department of Design and Construction officially commissioned the design of the future 40th Precinct Police Station to BIG, one of the current most successful architectural firms in the world, mostly known for their didactic (if not patronizing) way to explain their projects to clients and the public, as well as for the ‘hip’ pictorial characteristics of their buildings. Given the consistent lack of concern from this architecture office for any political issues (which is itself a political positioning), we cannot even accuse them to be disingenuous when they write “the 40th Precinct will also house a brand new piece of city program: the first ever community meeting room in a precinct. With its own street-level entrance, the multipurpose space will contain information kiosks and areas to hold classes or events, encouraging civic engagement with the precinct”

I don’t think that this is disingenuous from my end to associate the existing Harlem 28th Precinct building with the one proposed by BIG a few miles North in the Bronx. Of course renderings tend to polish the aesthetic of a yet-to-be-built architecture, but this new building will have a lot of difficulties hiding the bunker characteristics of its architectural typology. I don’t think that this is disingenuous either to assume that a “a community meeting room” in a building like this one will not experience a strong affluence, regardless of the “civic engagement” of the neighboring communities — especially when such a civic engagement might consist in the protection of locals against the police.

The problem here, as in Ingels’s work, is not its didacticism per se. Being able to explain yourself to the public is an admirable skill. But what, exactly, is being explained? All of Ingels’ metaphors and games are compelling right up to the point where they have to reckon with imperfection or the inability to have it all. That is something that optimism (or techno-optimism, a major theme in the Rolling Stone profile) cannot solve. It is also the sort of discursive void that characterizes Arkinoid as a game.

You can play Arkinoid for yourself right here.

The post Bjarke Ingels’s new game is everything good and bad about his architecture appeared first on Kill Screen.

I fell in love with a Soviet robot and all I got was hacked

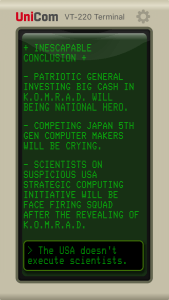

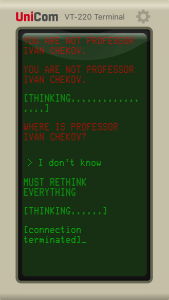

You get a message from an unknown number that doesn’t say much more than “hello,” and after a brief response, those dreaded words: “your device has been compromised.” You splutter and demand answers. The person on the other line is unhelpful; weaves some grand tale of identity theft and infinitely valuable lost codes lingering in hyperspace—then, without further ado, he connects you to another system. The music becomes more ominous; the faux-iPhone messenger turns into a green retro display, and the mysterious and threatening K.O.M.R.A.D. greets you.

But you’d be kinda shaken up too if you’d been left alone to stew for 30 years. And so K.O.M.R.A.D., a Soviet AI that was programmed to 1) nuke stuff, and 2) be scary, isn’t doing great. It’s struggling with English, for one, as there’s sadly no option to continue your conversation in its native language (native input?). The computer’s imprecise speech lands somewhere between second language growing pains—I feel you, buddy—and a child’s mismatched tenses and overeager plurals. It gives K.O.M.R.A.D. a sweet but probably unintentional charm. The computer prods at your flimsy disguise as its creator, but it also tentatively reconnects once it has discovered your deception, as if it slammed the door before it was quite done talking to you yet.

a sweet but probably intentional charm

The specter of hackers and codes and whatnot hangs over your interactions with the AI, but in the meantime it tells jokes, laments its mentor, self-consciously censors itself, and copies a quiz out of Cosmo magazine to determine if you two are well-matched to work together (read: you just got asked out by an AI, which means you better pass this test to live your best life). It even sings you a little song. Off-hand, once your identity has been exposed and the mystery heats up, it mentions that whoever connected you—fake iPhone hacker man—is still there, hovering somewhere in the ancient Soviet hyperspace, watching.

That’s all well and good, K.O.M.R.A.D., but you should ask me to be your boyfriend again.

Pick up KOMRAD on the App Store and solve the mystery, or date the robot, or something.

The post I fell in love with a Soviet robot and all I got was hacked appeared first on Kill Screen.

Alleged pitch for an unreleased Silent Hill game turns up

An alleged 2006 pitch for a Silent Hill game has shown up online. Created by Climax Los Angeles—also responsible for Silent Hill: Origins (2008) and Silent Hill: Shattered Memories (2009)—the game was originally planned as a PlayStation 3 exclusive title.

The pitch was uploaded by the YouTube channel PtoPOnline, and shows us that the game would have taken place in an old military base, repurposed by a religious cult. The 10 minute video shows main character Father Hector Santos exploring, engaging in combat, and solving simple puzzles. An El Paso, Texas priest, Santos travels to the town of Coyote Flats, Arizona after receiving a phone call from his niece, Anna. As one may expect from a Silent Hill game, the town has effectively gone to Hell, existing in two different states of existence: “Normal” and corrupted by memories of Silent Hill’s past.

nurses and Pyramid Head were all expected to make an appearance

Being a priest, Santos would have had to purify parts of the town gone awry—with the video explaining that water would play an integral part of the game. Vehicle sections were also planned for the game, giving Santos access to his pickup truck after a section of town was “cleansed,” and staple enemies such as nurses and Pyramid Head were all expected to make an appearance in the game.

After publisher Konami passed on its original pitch, Climax slightly reworked its story and game to create the pitch for Broken Covenant, which was planned as an episodic game that would release in one hour chunks. The studio had no success pitching this either, despite, as the video explains, its willingness to expand to the Xbox 360 if necessary. Differences in the two pitches can be found in detail in PtoPOnline’s video (shown above).

This, of course, is not the last story of an un-released Silent Hill game. In April 2015, Konami cancelled Silent Hills, a joint project between celebrated game maker Hideo Kojima and horror director Guillermo Del Toro, and removed its demo, PT, from the PlayStation storefront. You can read about some of PT’s long-hidden secrets here.

The post Alleged pitch for an unreleased Silent Hill game turns up appeared first on Kill Screen.

The “New Weird” In Videogames

Defining a genre is a troubled process the moment a discussion of its elements begin. Those nebulous divisions that separate detective and gothic fiction, science fiction and horror, adventure and fantasy; all seem built on shaky foundations as tropes and archetypes bleed into each other. More often than not, studying the progression and evolution of genres begins with the understanding that such genres are seldom fixed, codified strictures.

Such was the case in 2003 when a group of writers began an online conversation about a genre known as the “New Weird.” Though the New Weird, like almost every other genre, had its antecedents reaching decades before the movement had a name, its watershed moment was likely the popular reception of China Miéville’s Perdido Street Station (2000). Set in a world that blended magic (here, called “thaumaturgy”), complex alien biologies, and Victorian-era technology, Perdido Street Station takes place in the fetid city of New Crobuzon, built on the bones of ancient creatures and populated with humans and convincingly-drawn humanoid characters called “xenians.“

Bizarre technologies and nonhuman beings are mainstays in sci-fi and fantastic fictions, but what feels fresh from Miéville comes from his observant, urgent literary eloquence. Part of his aesthetic comes from rigorous political critique and a refusal to distinguish between the trappings of pulp fictions and the high styles of what are more traditionally considered “literary” fictions. In an interview with 3:AM Magazine, Miéville explained his fascination with genre fiction, saying, “The reason I like SF and fantasy and horror is that to me it’s the pulp wing of surrealism.” For him, these genres remain radical and challenging, and in his writing, he constantly tests the boundaries of literary traditions and styles—whether he’s writing about cities that occupy the same space (The City in the City, 2009) or replacing the sea and the leviathan of Melville’s Moby Dick (1851) with an infinite system of railroads and a giant white mole (Railsea, 2012).

it seems we only seem to have discovered the genre after it has been in effect

So, when writer and noted genre-troubler M. John Harrison posed the question, “The New Weird. Who does it? What is it? Is it even anything?” he—inadvertently or with twisted purpose—brought into question the purpose and function of genre in the midst of its constant reinvention. This question forms the central philosophy behind Ann and Jeff Vandermeer’s anthology of the genre, aptly-titled The New Weird (2008). In the anthology’s introduction, Jeff Vandermeer provides a working definition of the New Weird in the 21st century:

New Weird is a type of urban, secondary-world fiction that subverts the romanticized ideas about place found in traditional fantasy, largely by choosing realistic, complex real-world models as the jumping off point for creation of setting that may combine elements of both science fiction and fantasy. The New Weird has a visceral, in-the-moment quality that often uses elements of surreal or transgressive horror for its own style and effects…New Weird fictions are acutely aware of the modern world…[and] relies for its visual power on a “surrender to the weird.”

Unlike the weird fiction of H.P. Lovecraft and the pulp horror of Weird Tales that seal the images of horror away in tombs, undersea cities, or indecipherable grimoires, the New Weird brings that weirdness down from the realm of cosmic unknowability and reflects in a twisted version of our banal world. China Miéville, Jeff Vandermeer, Michael Moorcock, Steph Swainston, Mary Gentle, and others embrace discomfort by combining the quotidian with the grotesque, defamiliarizing the realities of contemporary life with genre-bending literary prose that never overshadows the surface reality of the text.

It should be unsurprising, then, to see the New Weird stretching its tendrils toward videogames as well. And, much like the literary movement it draws from, the New Weird manifests more often in the fringes. Failbetter Games, for instance, began building a complex world in Fallen London (2009), a chose-your-own-adventure game set in an alternate Victorian London. A catastrophe sent the eponymous city beneath the surface and it now sits on the edge of a subterranean ocean called the Unterzee. In Fallen London the player makes her name through any available means, whether using networks of street urchins to gather information for blackmail, divining secrets in the flight patterns of bats, consorting with devils who made their way to London from Hell, or through politicking among the city’s elite. Failbetter’s next game Sunless Sea (2015) moved the player out of the city and bestowed on her the role of steamship captain who explores the Unterzee, encountering mystery and madness in equal measure.

genres are seldom fixed, codified strictures

While Failbetter’s games focus more on mixing the mundane with gothic fantasy in a way that echoes the New Weird, Kitty Horrorshow’s ANATOMY uncovers a horrific physiology underneath the mundane fixtures of domestic space. The game tasks the player with finding cassette tapes in a suburban house, and as each tape elucidates a complex theory that discusses the architecture in terms of human biology, the house seems to awaken. Horrorshow peels apart the layers of comfort we associate with the concept of “home.” She builds an atmosphere of discomfort that bears the markings of a post-Lovecraft New Weird aesthetic by moving eldritch horror from the unknowable cosmos to the haunted space of a living room.

Each of these games trouble the constraints of their genres, but more importantly, they do so with sharp, insightful writing. Playing Sunless Sea as a game about amassing wealth through successful adventures is almost impossible—or at least painfully dull. Instead, it urges the player to venture out into the black morass of the zee and embrace an inevitable madness in the hopes of finding a good story. ANATOMY similarly asks the player to “surrender to the weird” in a house that appears to be gaining sentience. Few games demand this tacit agreement to embrace the weird instead of keeping her assured in a place of exceptionalism in a bizarre world.

Most big release games shy away from the philosophy of the New Weird, using it more as a colorful place to function as sort of haunted house rather than insist on its normalcy. BioShock (2009) is perhaps the best example with its underwater city of Rapture provided a heavy dose of weirdness to explore, but, since the player only arrives in Rapture after a widespread drug-induced apocalypse, she never has the opportunity to experience the city in a state of normalcy, thus removing the uncomfortable tension between the mundane and the alien so important for the New Weird.

Likely, the most successful mainstream game that samples aspects of the New Weird is Arkane’s Dishonored (2012). The setting of Dunwall, an architectural amalgam of 19th-century British port cities, is replete with otherworldly technologies powered by oil harvested from whales, and ancient magics haunt the fringes of the city. Though the game’s characters and story of revenge and political intrigue is unremarkable, its world of poverty, plague, biopolitics, religious extremism, and hermetic mysticism functions with such regularity that it doesn’t bother with unnecessary exposition. From its opening in which a cruel-looking barge carries the corpse of leviathan for harvesting to an opulent masquerade with lavish, bizarre costumes, Dishonored insists that the player accept a world not unlike Miéville’s New Crobuzon with a similar surrender to a new normal.

Few games demand this tacit agreement to embrace the weird

Dishonored furthers this delve into the weird by encouraging the player to rethink how she explores her environment. Corvo Attano, the protagonist, is granted arcane powers from the Outsider, a satanic trickster who materializes at times to comment on the player’s actions. These eldritch “gifts” and the retrofuturistic gadgetry at Corvo’s disposal allow for complex methods of assassination and traversal. Levels are designed vertically, and they permit dazzling feats of movement and execution. Teleporting across rooftops to set up a perfect kill in which the player can freeze time and move a guard in the path of his own bullet has led to some impressive instances of space/object manipulation. But more importantly, scuttling across the rooftops acquaints the player with a highway system above the narrow alleys patrolled by the city’s guardsmen. The player gains an intimate knowledge of how the city folds in on itself, becoming more entwined with itself as dilapidated roofs spill into impoverished streets. The view from the top shows the city’s history as the wealthy sit above street thugs, but the player can transgress such boundaries through the abilities bestowed on her by an Outsider, an analog for an agent of the weird working to free fiction from generic constraints.

Other games in various genres have, of course, used a similar template, but few offer a world that compliments such style so completely. The best window into the weirdness of Dishonored manifests in the Heart, a mechanized “heart of a living thing” that shows the locations of runes and charms used to augment Corvo’s powers. More importantly, aiming the Heart at certain characters or environments reveals cryptic information about Dunwall and its inhabitants. When pointing the heart at Samuel the boatman, a breathy voice explains, “He has many scars. Some from the phlegm of the river krusts, some from the nameless monsters of the deepest oceans.” The player can learn, too, that Callista “dreams of the decks of whaling ships fast after the beasts of the sea. But alas, she is a woman.” In a few short sentences, the Heart hints at horrors in the depths of the sea as well as the gender politics of a city, a blend of the supernatural and the uncomfortably familiar in equal measure.

More so than any other tool, the Heart enriches the player’s understanding of the world should she choose to use it. The sadness that saturates the Golden Cat brothel becomes more tangible when the Heart tells us of the madame’s cruelty and the plight of the women who work under her. Whispers of the “doom of Pandyssia,” the Academy that “cuts the flesh of the dead,” the distant screaming of whales, the city’s history of being “built on the bones of the old ones,” and the dark influence of the ambiguously evil Outsider expand the world beyond the player’s limited experience with it. If the New Weird’s project is to de-romanticize what we come to think of literatures set in supernatural world, Dishonored’s delivery of information that refuses to separate the magic and mundane and its aesthetic of gloom and dirt delves into a fiction that is truly unlike its popular contemporaries. It hides its mysticism in trash-filled streets, covers its incantations with drunken shouts and weeping plague victims. In that respect, Dunwall remains an uncomfortably modern version of a fantasy city: terminal, crazed, and mean.

With the release of Dishonored 2 on the horizon, there’s some hope for the New Weird in videogames, but, much like its literary counterparts, it seems we’ve only discovered the genre after it has been in effect. Even Dishonored has its weird antecedents in the Thief games that released decades before it. In acknowledging the aesthetic potential of the New Weird in games, I think we need to look back at what we may have missed or are currently neglecting in the margins of creativity. “New Weird” is only useful as a discussion starter, a curiosity that comes from a love of the fictions we cannot stop prodding in hopes of discovering new aesthetic modes by troubling the boundaries of genre.

The post The “New Weird” In Videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 19, 2016

YIIK’s demo probably has everything you love about 1990s JRPGs

To say the Japanese role-playing game is a prominent genre is an understatement—it has influenced videogames tremendously over the years. From Final Fantasy VII (1997) to Earthbound (1994), Dragon’s Quest (1986) to Persona (1996), JRPGs introduced expansive stories and memorable characters that still live on in popularity today. Not to mention, the JRPG is a genre that’s constantly reinventing itself, exploring new problems, themes, and design styles. You can look at the overlapping cartoon realities of Kingdom Hearts and the World War II narrative of the Valkyria Chronicles series for a taste.

Ackk Studios’s upcoming game YIIK: A Postmodern RPG is not only interested in the 1990s JRPG, it embraces the genre and does something quite different with it. To give players a taste of what the full game will entail, the studio uploaded a demo called YIIK: Episode Prime – “The MixTape Phantom and the Haunting of the Southern Cave” onto itch.io. While Episode Prime doesn’t focus on any major moments in the full game, it captures the feel it’s going for.

YIIK embraces the era from a 2016 perspective

YIIK takes place in 1999. It starts when a girl named Sammy Pak is whisked away in the middle of the night by a supernatural presence, leading a group of friends on an adventure to find out what happened to her. The game is about “the strange things you invite into your life when you go to forbidden places.”

What’s so interesting about YIIK isn’t just the fact that it explores JRPG game designs from the ’90s. It’s also the way YIIK embraces the era from a 2016 perspective. From the ways the characters dress to the places they visit, from the game’s 1990s paranormal message boards to its soundtrack, YIIK looks to tell a ‘90s Earthbound-esque story in the same vein that Netflix’s Stranger Things is a love letter to the small-town supernatural thrillers of ‘80s cinema.

YIIK: Episode Primes reimagines the gameplay and settings of such series as Mother and Persona by being tongue-in-cheek about its inspirations, allowing the player to explore suburbia for information or collect cheese burgers and fountain drinks in treasure chests. By doing so, Ackk brings the humor and writing behind these series to a 2016 audience: entertaining both fans that grew up in the ‘90s as well as those who have only enjoyed these past games through emulators and virtual console ROMs.

YIIK: A Postmodern RPG is heading to Steam, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, and Wii U in the near future. The game’s official launch date has not been announced. Until then, you can keep an eye out on Ackk Studios’ official Twitter.

You can download the Episode Prime demo on itch.io. Find out more about YIIK on its website.

The post YIIK’s demo probably has everything you love about 1990s JRPGs appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Crusader Kings II mod capble of generating huge, alternate histories

Like the procedural culture experiments currently going on in Ultima Ratio Regum, a recent mod for the grand strategy game Crusader Kings II (2012) is trying its hand at procedurally generating a whole world. The mod, created by user Yemmlie, manufactures history “from its first exodus from Africa” onward, creating religion, language, legal systems, and more, all from scratch. Nothing from the base game remains except for the map, which can be randomized if desired, while new factions and cultures struggle for control of land and resources.

entire dynasties are developed

Even though the simulation isn’t as detailed as the vanilla game, the CK2 Generator still boasts an impressive amount of complexity for an algorithm. Entire dynasties are developed, with births, deaths, and family trees all accounted for by the procedural generation. Conflicts of inheritance can be simulated; wars can take place between kingdoms; land can be conquered and settled and re-conquered. It generates an entire world and population to an extent that many hand-made fictional worlds never reach.

Unfortunately, this ambition seems to take its toll on the actual Crusader Kings engine: the subreddit is full of would-be modders who’ve had to endure crash after crash while trying to get the thing to load. Right now it seems to be something to try at your own risk while modders isolate what’s causing the bugs. If and when it becomes stable, though, the mod should lend itself to hug and rich generated histories at the push of a button (well, almost).

If you want to try your luck at generating a whole new world, the mod’s subreddit has a guide to get you started.

The post The Crusader Kings II mod capble of generating huge, alternate histories appeared first on Kill Screen.

An upcoming game about discovering who you are while hitchhiking

Whenever you set on a trip across the United States, or any country in fact, more often than not you’ll encounter a person or two standing at the side of the highway, waving for you to stop and give them a ride. Perhaps you hesitate since you don’t know who they are: what’s their background and what have they done in their lives? But what happens if even they don’t know who they are and want your help in answering that question.

This is the starting point of Patrick Rau’s latest game. He’s the founder of kunst-stoff, and the creator of several award-winning games, and was joined by a team including author Dan Mayer for this latest effort. The game is simply titled Hitchhiker, and it puts you in the shoes of a hitchhiker who has to unravel the mystery of who they are and where they’re headed. If that concept doesn’t draw you in then it may help to know that the game’s art style is inspired by Firewatch and Gone Home (2013). It’s said to be set in a “dreamworld of hitchhiking and storytelling.”

the drivers don’t actually exist

Hitchhiker will have you take several rides in order for you get to know who you are and discover your personal background. Whenever the driver talks to you, you’ll be prompted with multiple lines of dialogue for your reply, with each choice directly impacting the course of the game and changing “your path across the highway world.”

In addition to that, you can interact with the environment around you, “turning on the radio, rolling down the window, looking into the glovebox.” Having VR support means that the simple act of looking around and soaking in the environments is encouraged too. In a brief discussion with Rau, he revealed some minor details about the game’s characters, saying that the players will slowly realize that the drivers don’t actually exist in the true sense of the word, with only one other character who really exists, and he’s “a second, mysterious hitchhiker, who appears as a kind of enemy / antagonist to the main character.”

In all these descriptions, it may seem that Hitchhiker is, in some way, aping the reverie state of Glitchhikers (2014). In fact, it seems to have a more clear storyline than that game, which focused more on musing on the state of the universe and discussing the surreal experience of night driving. The question that clears up the confusion is: “What goes on in the subconscious mind when you lose somebody you love?” You should be able to see where Hitchhiker will go from there.

Find out more about Hitchhiker on its website. A Kickstarter campaign should launch early next year, with a full release scheduled for later in 2017. It will be available for PC and have VR headset support.

The post An upcoming game about discovering who you are while hitchhiking appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers