Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 51

September 26, 2016

Prepare for the Clinton-Trump debate with a political drinking game

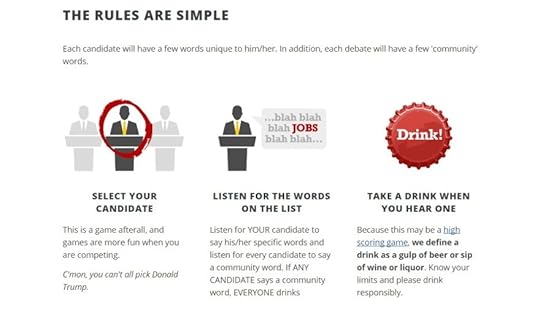

If the current presidential election has not yet driven you to drink, the first of three debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump scheduled for Monday (yes, today) may well prove to be the tipping point. Before it has even begun, it is already infuriating: one candidate is likely to be declared presidential if they manage to avoid a sudden bout of incontinence, whereas the other’s supporters have been preparing for this injustice with their normal reserve. Is it over yet?

The desire to drink through debates is oftentimes a purely rhetorical gesture meant to signal just how frustrating the whole exercise is. Some politicos do, however, drink through the pain—usually with primitive rules. For the discerning connoisseur, however, there is the work of DebateDrinking.com, which is now in its second electoral cycle of producing political drinking games.

drink whenever that candidate says one of their pre-selected words

“We started about five years ago with the Republican primaries in 2012, and did most of that on Twitter,” says Debate Drinking creator Dan Mueller. When the general election rolled around, Mueller was approached by a livestreaming service, and that is where the drinking-game-as-esport concept came about. “Watching us sit on our couch would not be interesting,” Mueller says, “so we came up with a live scoreboard.” That model, which has now moved to YouTube, has been used ever since, with State of the Union addresses filling the void between campaigns.

“We did all the primaries for it feels like a year and a half now,” he says.

Under the rules for Debate Drinking’s current game, you pick a candidate to follow for the evening, and drink whenever that candidate says one of their pre-selected words. You are not, however, at risk for whatever the other candidate says. Choose wisely. This choice mechanic, Mueller says, puts the game back in drinking games: “A lot of drinking games online, they’re not really games. A game involves competition. If everyone’s drinking to the same words, it can be a fun party, but it’s not a game.”

In addition to their candidate’s words, all players drink when shared words, which reflect bipartisan political pabulum, are uttered. One such word in the latest version of the game is Reagan. “In the past we tried to do a lot of topical things that were in the news,” Mueller says, “but the more we’ve been doing them we’ve had fun with the more filler phrases: the phrases that are more personality based, the things the candidates bring up on their own.”

“We don’t want it to get too far out of hand”

This, inevitably, brings us to the most contentious part of drinking game design: the alcohol. As a rhetorical device, the joke is usually that you’ll drink yourself into a stupor because politicians so frequently say dumb things. That, however, would be an ill-advised strategy for the designer of an actual drinking game. In part, Mueller solves this problem by defining a drink as a sip of wine or beer as opposed to a more oppressive quantity. “We don’t want it to get too far out of hand but we don’t want it to be a low scoring game,” he says. “In an ideal setting we end up with scores in 30-50 range. We calculate that’s 3-4 beers.”

If there’s one person who won’t be drinking during the Trump-Clinton debate, it’s Mueller. He’ll be busy operating the scoreboard, which is a task best left to the sober. It occupies enough of Mueller’s attention to drown out the actual political discourse as it happens. “I usually end up watching it again on C-Span so I can actually watch and hear what they’re saying,” he says, “because when I’m watching it with the scoreboard I’m just watching for words.”

After Monday’s debate, this routine will be repeated three more times over the rest of the campaign: there are two more presidential debates as well as one between the vice-presidential candidates. Mueller is already thinking of other political events to fill the downtime between elections. He is, however, resigned to those events being more scarce.

“We don’t recommend having a hobby that comes up for a couple days every four years,” Mueller says, “and yet we still feel very unprepared for Monday. But we’ll have fun.”

Find out more about DebateDrinking over on its website.

The post Prepare for the Clinton-Trump debate with a political drinking game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Wheels of Aurelia sputters onto the race track

Elevator pitches have the benefit of being ideas rather than actual things in the real world. With the right pitch just about anything can sound promising. Take communism, for instance—a system that, on paper, reads like an egalitarian haven, promising equality, fairness, and a stable life for everyone. It often doesn’t play out so well when put into practice, but the idea captivates so much that it lead to countless wars, dictatorships, and deaths.

Wheels of Aurelia, set in a 1970s Italy reeling from feminism, communism, revolution, and terrorism, sounds better as an idea than it plays. You are Lella, a “restless” woman driving to France with her newly found companion, Olga, down Italy’s famous Via Aurelia. As a narrative racing game, it appears to promise conversation and the open road—perhaps exploring how the wide expanse and sense of motion of a road trip often leads to discussions you may not regularly have. As a political game, it hopes to tell you about a fascinating moment in history through the perspective of average, everyday people.

Wheels of Aurelia falls short on just about all fronts

In practice, Wheels of Aurelia falls short on just about all fronts. Opening with Lella speaking to herself while driving alone at night, the first lines of dialogue capture the game’s inescapable artificiality. Aside from having a full blown conversation with herself, with dialogue options and all, Lella is even kind enough to refer to herself by name (you know, in case anyone who needs that information is only just tuning in). Everything feels forced in Wheels of Aurelia: whether it’s shoving a racing game into a narrative game, or its woefully inorganic dialogue, or the many high-minded political topics that get unceremoniously thrown onto the track to collide head first with Lella’s car like so much road kill. When I originally tried out the demo last year, I described the combined racing and narrative aspects as coming across like a “texting-while-driving-simulator;” an issue which appears to have only grown more pronounced with time.

The experience of trying to process and engage in conversation while (attempting) to navigate the game’s janky driving mechanics is nothing short of maddening. Eventually, after a few playthroughs, I decided to just abandon the dialogue altogether whenever I was expected to race, which at the very least allowed me to engage with the racing on a deeper level. But with only a single button press for acceleration and no consequence for crashes, those depths were admittedly pretty shallow. But, hey, at least I was finally able to outrace that random asshole who, for no discernible reason, calls me a slut and challenges me to a race.

Most of Wheels of Aurelia’s narrative and dialogue is characterized by these kind of jarring, inexplicable artifices. Designed to be replayed several times, each playthrough is only about 15 minutes, with the path you choose leading to one of 16 different endings. You are painfully aware throughout that you are playing a videogame, whether it’s by watching the limited, inelegant, and jumbled dialogue system sputter to try and keep up, or the disregard for consistent characterization, or numerous glitches that actively get in your way while driving. (After almost a dozen playthroughs, I have yet to be able to pick up one of the hitchhikers along the road because if you don’t time when you pull over to the pitstop perfectly, you will clip into the side railing and spiral away with no ability to reverse or try again until the next playthrough.) The more times I played, the more painfully aware I became of the game’s limitations on both a mechanical and narrative level. Events like a bank robbery happen and, as you’re racing away from the cops, the conversation gyrates between freaking out over this abrupt turn of events and casually discussing the robber’s political beliefs.

Yet, for all its shortcomings, Wheels of Aurelia never lacks ambition or daring and you can’t help but want to respect it for that. During the drive, Olga suddenly blurts out that she’s pregnant—often at the most inopportune moments, like when you’re racing that asshole dude who called you a slut and can’t divert your attention from the road to give her support. But it doesn’t really matter either way, because Wheels of Aurelia handles abortion with the tact and subtlety of Bojack Horseman’s Sextina Aquafina. At most, you have the option of being somewhat non-judgmental toward Olga. When the conversation forces you to question her reasons for going through with the abortion, you can either completely ignore her right to make her own damn decisions about her body, or you can more gently ask, “I don’t want to change your mind, just understand.” To which Olga replies, “There are a lot of reasons.” To which you can respond with, “Name one,” or “Were you abused.” The exchange is just one example of the game’s cringe-worthy attempts to broach serious subjects.

For all its shortcomings, Wheels of Aurelia never lacks ambition or daring

Wheels of Aurelia’s bullheadedness in the face of just about all its sensitive and political topics is, perhaps, an attempt to depict a specific time. Despite calling herself a feminist, perhaps Lella is simply a product of her circumstances, a person born in a place where abortion is considered an unforgivable sin no matter how “with the times” one might believe themselves to be. But even that choice doesn’t hold up. Later, the girls return to the topic with Olga asking, “Do you think abortion is a bad thing?” Lella can respond by either cavalierly declaring it just a medical procedure, or soberly labeling it a traumatic emotional experience.

This is the kind of deftness with which Wheels of Aurelia approaches all its high-minded topics. At some point, someone’s scarf leads to a discussion about worker rights—or something, I’m not entirely sure because the game also assumes you’re already pretty caught up on the finer details of Italian culture in the 1970s. At another point, you have the option of literally asking, “Got any political opinions?” as we robot-humans are wont to do during lulls in conversation. At best, the characters feel like talking heads for abstract concepts and political stances. At worst, they’re offensively inhuman, an apparent jumble of code wearing a fake mustache and asking where the nearest vehicle refueling facility is. It’s a shame, because the negligible characterization leads the game to be equally unsuccessful as an attempt to steep you in Italian history and culture. Lacking relatable personalities, and with an isometric art style that looks pretty enough on its own, but fails to give any sense of place, Via Aurelia feels more like a backdrop rather than a character worthy of the game’s title.

Somehow, despite its failure to deliver on almost everything it sets out to do, you can’t help but keep rooting for Wheels of Aurelia to turn things around. At times, when the dialogue manages to work in a sensical fashion, you catch glimpses of the pithy exchanges that might’ve been. The game’s big ideas and aspirations seem intoxicating—until they’re a real thing happening on your screen. At the risk of overextending my metaphor, like communism, Wheels of Aurelia appears on the surface to be a celebration of human empathy. In practice, it’s a system that forgets to account for the human spirit (while also harboring some seriously iffy ethical opinions).

All in all, the game feels like a tourist trap rather than a destination.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Update: It was later pointed out by Santa Ragione that the game’s auto-drive function will automatically pick up hitckhikers if the player releases the acceleration button, though this mechanic does not apply to winning the races referenced in the review.

The post Wheels of Aurelia sputters onto the race track appeared first on Kill Screen.

Let’s all hold hands and play Shu on October 4th

Some may say that the platform genre is oversaturated, but then the hand-drawn art and hand-holding playfulness of Shu comes along to throw that argument into the trash. It’s due out for PlayStation 4 on October 4th with a PlayStation Vita version arriving before the end of the year too. So keep your faith in the platformer until then, yeah?

The game follows the story of Shu, who you’ll guide through towns to save villagers, trying your best to outrun the apocalyptic storm trying to consume the whole world around you. As you run across the screen, you grab the hands of the villagers creating a conga line, each of them granting you new abilities required to outpace the storm.

the game they had wasn’t the one they wanted to deliver

After a long silence, and having missed its original 2015 release date, creators Coatsink Software decided to finally speak up about where Shu is currently at. As designer Jonathon Wilson revealed, it turns out that Shu has changed since the team last said anything about it.

Coatsink realized near their designated 2015 release date that the game they had wasn’t the one they wanted to deliver. So they returned to the drawing board, overhauling multiple aspects of Shu, including the storm’s design and appearance, the level structures, the villagers’ special abilities, and more. The team also added two new features: time trials and leaderboards. These allow for a game that encourages competition among friends to achieve either the fastest time or the highest score, making it a game more about speedrunning, if that’s your kinda thing.

One of the big features the studio decided to cut was the loss of a special ability if one of your villagers gets eaten by the storm. The reason for this, according to Wilson, was that “it created a whole host of problems.” Meaning those who lost their villagers along the way would have to experience a “duller route than those who managed to keep all of the villagers alive.” The idea now is that everyone will be able to enjoy a lively route regardless of their ability.

Shu releases on October 4th for PS4, priced at $11.99, with cross-buy meaning you won’t have to pay extra for the PS Vita version.

The post Let’s all hold hands and play Shu on October 4th appeared first on Kill Screen.

I’m feeling some scarlet curiosity about the new Touhou game

Being bored sucks. There’s many ways that we find ways to cure our boredom: videogames, books, music, watching a decent show or movie. For the 500-year-old vampire Remilia Scarlet, those petty activities are far below her. Her boredom is on a whole other level, one the likes of which her maid companion Sakuya Izayoi has never seen before. Luckily, there’s a neighboring monster that’s terrorizing the countryside near her manor, the adequately titled Scarlet Devil Mansion. Finally, the excitement she deserves. That is, until the beast destroys her home, and then it’s just a case of revenge.

That’s the basic plot for the new XSEED-localized action-adventure Touhou: Scarlet Curiosity (developed by Ankake Spa), just one of many fangames crafted in the bustling The Touhou Project community. The Touhou Project didn’t get its start in action-adventure flurry. In fact, it emerged from something quite the opposite: danmaku games, probably more familiarly known as the bullet-hell genre (typically 2D games where gleaming projectiles coat most of the screen).

I first learned about The Touhou Project a few years ago. I’m kinda ashamed to admit that, since that’s a mere dent in the two decades that Touhou has been around, its first game popping up sometime in 1996 in Japan. Touhou’s a weird series, emerging as a cult-favorite bullet-hell title originally by developer ZUN, who independently programmed, musically scored, and created graphics for his first games. Then the series took on a life of its own through doujin culture—where fans created their own iterations of Touhou. With ZUN’s blessing, spin-off games, music, cosplay, and anything else that people could create donning the Touhou name came into existence. Of course, doujin games are hard to come by on major platforms like the PlayStation 4, and official localizations of them are even more rare. But recently, all that has changed.

In comes Touhou: Scarlet Curiosity, the second Touhou game to make its way westward with an official localization this year. The first Touhou game to receive a western release came last year through Playism, but it wasn’t translated by any means. Earlier in September, NIS America published Touhou Genso Rondo: Bullet Ballet, which is not only a mouthful to say, but also a shoot-‘em-up-fighting game hybrid of sorts. Touhou: Scarlet Curiosity is the latest effort in ZUN and Sony’s Play! Doujin distribution plan, created in an effort to bring fangames to PlayStation 4.

Boss fights still star incredibly charming characters

As I said, Touhou: Scarlet Curiosity isn’t your atypical, bullet-screen blanketing Touhou experience. For that, you’d have to look elsewhere, like to ZUN’s own games. Yet, it does share glimmers of similarities (which makes sense, still bearing the Touhou name and all). Its boss fights still star incredibly charming characters (and both Remilia and Sakuya—Scarlet Curiosity’s two playable characters—have been bosses in past mainline Touhou games). Battles still see you narrowly dodging glowing spheres. Though being a 3D game, you have the option to simply leap over the orbs (which, honestly, offers its own challenges and strategies).

Touhou: Scarlet Curiosity isn’t too hard of a game, at least in the hours I’ve played of it destroying all fairies, wolves, giant centipedes, and other folks and critters that cross my path. That might be where it feels the least like a Touhou game, which are known for their punishing difficulty. But really, Scarlet Curiosity isn’t trying to emulate the immensely hard difficulty of the games that inspired it. Instead, it’s paying homage to the colorful, endearing characters that the series has always had to offer. The sometimes-whiny sass of Remilia. The stoic but devoted demeanor of Sakuya. And everything else in between. Plus, I’ve always wanted to be a knife-wielding maid with a cute frilly outfit. Now with Touhou: Scarlet Curiosity, all of us in the West have a chance to don the guise of a vampire or a maid, and visit the remarkable land of Gensokyo. Given how rare that is, it’d be a shame to squander the opportunity.

Touhou: Scarlet Curiosity is available now on PlayStation 4 for $19.99.

The post I’m feeling some scarlet curiosity about the new Touhou game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Oh damn, a game inspired by Albert Robida illustrations is on the way

Zipping along an elevated restaurant and opera house, there are flying cars, buses, and other ships. The sky is teeming with these vehicles, transporting Victorian-garbed folks to and from their destinations. This is the futuristic world envisioned by 19th century artist Albert Robida in Le Sortie de l’opéra en l’an 2000. This is the same world inspiring Voici, an upcoming game being created by Rotterdam-based designer Joost Eggermont. Under the backdrop of a retro-futuristic city, Voici oozes the same kind of playfulness and charm as found in many of Robida’s prescient works.

Two years ago, while looking for visual inspiration, Eggermont stumbled upon Robida’s science-fiction illustrations. Depicting a vertical city architecture, the illustrations echoed Blade Runner (1982) but with a dash of “fashionable Victorian style.” Eggermont says he fell in love with the character design of the flying machines which performed “almost aerial choreography.” Soon after, he found Robida’s science-fiction novel Le Vingtième siècle (1890). Marveling at the “great pictorial quality of the illustrations,” it made him want to explore the world further.

When asked about what fascinates him the most about Robida’s style, Eggermont points to his refreshing take of a steampunk world: “Instead of testosterone-steam and steel-driven airships, Robida draws these easy, floating, elegant lightweight airships … instead of carrying heavy artillery, [they transport] these lovely dressed women around. I loved how it showed this vibrant and fashionable women-centered world. [I] thought it would be nice to translate this to a game world.”

“It’s like becoming a tourist in your own work”

From the way Eggermont describes Voici, the game is quintessentially about the moments between our destinations. He says the game is about piloting aerocabs while trying to find routes around “this throwback vertical Parisienne cityscape.” As you try to get the “fashionable Parisiennes” to their destinations on time, you might “get [held] up by the Atmospheric Gendarmes or traffic jams, dissolve into smog, or end up hanging in the wires.”

Admittedly, though, Eggermont says Voici is still early in its development. Up until this point, his focus has mainly been on crafting the warm-toned visuals of the game. Only now is he starting to explore playable ways to weave the same “lightweight floating poetry” you get in Robida’s works. While a challenge, Eggermont is encouraged by what he’s starting to see: “Slowly creating this world you envisioned and putting it all together is always very rewarding. It’s like becoming a tourist in your own work.”

Voici is currently in development. Follow the game’s progress on Eggermont’s website , on Cartrdge or on Twitter .

The post Oh damn, a game inspired by Albert Robida illustrations is on the way appeared first on Kill Screen.

Sunless Skies promises a gloriously Victorian sci-fi tale

Rejoice! The stars are right! The stars are right because they are being murdered.

Sunless Sea (2015) introduced players to the lonely madness and terror of an underground sea. Its expansion pack, Zubmariner, is set to take players to the claustrophobic depths of that ocean on October 11. Now, the sequel to Sunless Sea has been announced—named Sunless Skies—and promises to take its blend of well-written prose and pensive cosmic horror out into the actual cosmos. Fallen London is going to space.

Sunless Sea begins with an epigraph from Joseph Conrad, expressing the central theme of the game: “The Sea has never been friendly to man. At most it has been the accomplice of human restlessness.” The player is an adventurer, setting out on a darkling sea for excitement and to discover the stories it holds. But Sunless Skies will exchange one kind of darkness for another, as the Traitor Empress has left Fallen London and the Neath behind for the “blistering, wonderful night” of the High Wilderness.

the science fiction of glass spheres for space helmets

In place of an underground empire is a stellar one (space, that is), as orderly and controlled in a way that only autocratic Newtonian mathematics and the predictable, elliptical orbits of Kepler can be. And, rather than a captain venturing out from safety, the player will control someone shunted out to the periphery of this perfect, ordered empire: bohemians, revolutionaries, and outcasts.

The Victorian element of the original game will be present, but the strain of sci-fi in Sunless Skies relies upon the pulpy, imaginative planetary romanticism of the early 20th century. We won’t see the high-tech, detail-oriented, ultimately scientific world created by Arthur C. Clarke or Isaac Asimov. Rather, Sunless Skies promises to be more of a space opera in the vein of H. G. Wells’s work. Think pulp inspired by Leigh Brackett, who wrote early science-fiction novellas with titles like “The Enchantress of Venus” and “Last Call from Sector 9G.” One can only hope to see the science fiction of glass spheres for space helmets and magnificently silly-looking ray guns.

Eve of Perelandra by James Lewicki

One particular influence may be more instructive: C. S. Lewis’s space trilogy. Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943), and That Hideous Strength (1945) are emblematic of an earlier kind of view of space. When the protagonist Elwin Ransom visits Malacandra (Mars), he encounters three distinct alien species: hrossa, séroni, and pfifltriggi. What makes these species truly alien is not their evolutionary distinctiveness, but the fact that they were not subject to original sin—that they were not fallen, unlike mankind. So, think of alienness and horror where the difference is ultimately spiritual and aesthetic, and not merely biological.

But, because this is a Failbetter production, think of the outlaw crew of Firefly piloting the titular ship of Event Horizon (1997). Because there is a revolution afoot and someone is murdering the stars.

Failbetter will be launching a Kickstarter campaign to fund Sunless Skies in February 2017.

The post Sunless Skies promises a gloriously Victorian sci-fi tale appeared first on Kill Screen.

The neglected history of videogames for the blind

The game starts with a black screen. A woman’s voice, speaking in Japanese: “Real Sound. Kaze no Regret. This software brought to you by WARP Inc.” A string quartet, swelling and romantic, begins to play—press the start button, and the music stops suddenly with the sound of a bell.

A light hiss of static. An acoustic guitar picking up the same theme as before is quickly joined by a ticking clock. A deep male voice starts to narrate: “Every so often, when you meet someone else, you have a feeling that it’s not for the first time.”

The screen remains black.

///

The 1997 Sega Saturn Japan-only release, Real Sound: Kaze no Regret, is a fully-voiced interactive romance game with elements of mystery and suspense, featuring two elementary school students with plans to elope, a portentous clock tower, and possible murders in the underground. With no visual elements for its entire runtime, it’s something like a choose-your-own-adventure radio play. In other words, it’s not a videogame, but an audiogame: a game in which graphics are nonexistent or optional and can be played through sound alone.

Its creator, Kenji Eno—who died tragically in 2013, at only 42 years old—was a game designer and composer, and one of the few figures working in videogames who had a consistent commitment to radical experimentation in everything he was involved with. Before this point, he was best known for D (1995)—an anxious and intense horror-puzzle game that forces the player to complete it within two hours without any way to save or even pause—and Enemy Zero (1996), an Alien-esque space station survival thriller scored by Michael Nyman, in which the enemies are invisible and only able to be located through the pitch and volume of the sounds they emit.

The braille instructions shipped with copies of Real Sound

It’s this special attention paid to sound within gameplay that gained Eno a following in Japan by those who were blind and of low-vision. After several of their fan letters, he met with many of these players in person, to see firsthand the ways in which they engaged with videogame software and hardware not originally intended to be accessible to them. These encounters served as the inspiration for Real Sound—Eno wanted not just to create a game “for the blind,” but rather a game in which a blind and a sighted person would have the same experience of playing it. In exchange for it being a Saturn-only release, Sega agreed to donate a thousand consoles to blind players—Eno himself included a copy of Real Sound with every console. At first glance, the game’s case looks like any other Sega Saturn game. But open the game’s packaging, and you immediately encounter something that hasn’t been included in any console game before or since: a sheet of instructions in braille.

Playing Real Sound as a sighted player, it’s hard not to be disoriented at first. Its dialogue—better acted than in any game I’ve played—cannot be skipped over or sped up by mashing a button repeatedly. We’re used to visual distinctions between “gameplay” and “cutscene,” where the former requires our active attention and the latter for us to sit back and relax; in Real Sound, the player must hang on every word, always listening for the next chime that indicates that you have to make an immediate decision as to how the story will go. I wasn’t sure what to do with my body at first; whether to close my eyes, look at the blank screen, or vaguely stare into space (I chose the latter). Small sonic details that I never would have noticed in a conventional videogame—like the moment-to-moment interactions between the musical score, the actor’s voices, and the elaborate sound effects—suddenly came together to form an entire world in a way I had never experienced.

the player must hang on every word

Real Sound is far from the first or only audiogame, though it is one of the very few ever released for major consoles. Soundvoyager (2006), a set of diverse and relaxing audio minigames within Bit Generations for the Game Boy Advance, was the first audiogame released by a major studio since Real Sound, though the absence of voiceover in its menus keep it from being fully accessible. Papa Sangre, a 2010 release for the iPhone/iPad, is a marvelously creepy experiment that makes full use of three-dimensional sound design (headphones are vital) and is an excellent introduction to the audiogame genre. Much more common are amateur homebrew audiogames for the PC—Audiogames.net maintains a list of hundreds. Bokurano Daiboukenn and its two sequels, some of the best examples of these, are free Japanese side-scrolling action RPGs in the style of Metroid or Castlevania, focused on exploring worlds, collecting powerups, and defeating enemies, all through sound.

Audiogames tend to be accessible by design—Amy Mason, in an article for the National Federation of the Blind, however, notes that most games played by blind and low-vision players are accessible to them only by accident. This was the case for Eno’s Enemy Zero, with the sound-based play centered around invisible monsters. Other accessible-by-accident games include text-based games like King of Dragon Pass (1999), Kingdom of Loathing (2003), and various interactive fiction works that can be used with screen access software (including text-to-speech programs). Even many 2D fighting games like Mortal Kombat are largely accessible as well, the audio cues being ample enough for a blind or low-vision player to play without too many issues, except for the maze of title, mode-select, and character-select screens. This is a problem that Mike Zaimont of Lab Zero Games addressed directly, updating the fighting game Skullgirls Encore (2014), so that all of its menus were fully accessible through text-to-speech programs. Other games take much more effort on the part of players to be made even slightly accessible. A Kotaku article earlier this year profiled Terry Garrett, a blind player who beat The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) after five years, using two speakers set in his chair that split the game’s audio to right and left channels in order to help him locate Link more effectively in his surroundings.

Whether accessible to blind and low-vision players on purpose or by accident, these games represent a tiny fraction of those that are made. Accessibility to deaf and hard of hearing players is better overall these days, but there are countless games that have crucial puzzles that hinge upon audio cues with no visual elements, lack captions to spoken elements, or rely on particular sounds or music to indicate where hidden objects are located or if an enemy is approaching. (Audiogames are, needless to say, largely inaccessible to deaf and hard-of-hearing players, though again incorporating detailed captions would even make many of these playable.) The message is clear: videogame culture tends to assume that all players have the same bodies that function in the same ways, and this assumption is rigid enough that even the most trivial tweaks that would make a game accessible—audio and visual cues, text that can be read with a screen access program, and so on—are not only rarely implemented, but often never even occur as a possibility.

Thinking about audiogames brings another, even more fundamental bias within videogames to the forefront, embodied by the term “videogame” itself: as a medium, videogames tend to privilege one sense, vision, above all else. Narratives of game development often center around the progress of computer graphics, from 8-bit to 16-bit to 64-bit, from 2D to 3D, from blocky polygons to vivid hyperrealism. Games are hailed for their renderings of faces, landscapes, water, and blood. Alternately, they’re praised for their character designs, unusual graphic stylization, or their incorporation of aesthetics of other visual media into their look, like watercolor painting, papercraft, or comic book art.

A game is muted so readily

Yet despite the importance of sound from the very earliest stages of the medium, when it comes to writing about games, the “audio” of audiovisual is relegated to the margins. This is true when it comes to playing games too, where as soon as sound is not strictly necessary to play a game, it becomes a completely optional part of the experience. A game is muted so readily, so casually, in order not to bother the people around you at home, in a car, or on a subway. Or maybe you just want to play in silence, or listen to other music. This is perfectly reasonable—it would be absurd to suggest that everyone should play games with the sound turned on at all times. But the fact that audio is treated as so optional when it comes to videogames again shows us a bias, one that means most people are perfectly willing to think, play, and write about games while only paying attention to what appears onscreen, and not what comes out of the speakers.

Audiogames are one way to confront this bias head-on: with no visual elements to talk about, you’re forced to contend with the intersection between interactivity and sound. Putting sound at the center of the story of a videogame amplifies other elements within the mix as well—there’s a neglected shadow history of the medium centered around the questions of audio, one that brings together games with cultures, communities, and technologies that aren’t usually talked about in this context. Blind and low-vision players are one; another is the role of the voice in videogames, a focus on which brings an array of long-forgotten games and pieces of gaming hardware back within earshot, few more forgotten than Nintendo’s Satellaview.

Satellaview with Super Famicom from Wikimedia Commons

While synthesized voices appeared in games as early as the beginning of the 1980s—the terrifying computerized speech in the arcade game Bezerk (1980) is perhaps the first example—the mid-to-late 1990s saw the release in Japan of a now-obscure peripheral that brought voice acting to the forefront. The Satellaview, a satellite modem for the Super Famicom (known elsewhere as the Super Nintendo) came out in 1995, and was designed to receive signals from St. GIGA radio station, which specialized in broadcasting content at fixed time slots to interact with certain Super Famicom games. Players could use the Satellaview to access “SoundLink” data, very much akin to a radio play. Sometimes, actors gave real-time walkthroughs to the featured game, but the real draw were fully voice-acted cutscenes, something that would be unthinkable with the standard Super Famicom hardware. Starting in 1995, three different Legend of Zelda games were released for the Satellaview—BS Zelda no Densetsu, BS Zelda no Densetsu: MAP2, and BS Zelda no Densetsu: Inishie no Sekiban (the “BS” stood for “Broadcast Satellite”)—with SoundLink actors providing full voice-over narration. Yet the full experience of playing these games cannot, as of now, be recreated: the SoundLink broadcasts meant to accompany them each happened several times, but then never again, an ephemerality we associate more with live performance than with videogames. In yet another symptom of the lack of acknowledgement in the importance of sound to the medium, perhaps one of the most crucial early experiments in combining games with storytelling has become little more than an esoteric footnote in conventional game history.

The same might be said, perhaps, of Real Sound: Kaze no Regret. A cult hit among a very particular group of players, it’s an oddity that accrued to its name several pioneering firsts—first audiogame on a television console, first console game fully accessible to the blind—that also unfortunately proved to be lasts (the two planned sequels never came to be). Yet this game, singular even within Kenji Eno’s legacy, still has much left to teach us: about the other stories to be told about videogame history; about paying attention to that which is all too easily ignored; and about rejecting small-mindedness in favor of committing to real accessibility and respect for all possible players. Or, in Navi’s words: Hey! Listen!

The post The neglected history of videogames for the blind appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 25, 2016

Weekend Reading: Real Funny, Scary Funny, Real Scary

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Where “It” Was, Adrian Daub, Los Angeles Review of Books

Stephen King writes stories set in a specific place; those small and mysterious places that have to be felt, not seen, along the coast of New England. And yet, tales marinated in personal childhood have resonated with the world over. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but King happens to be one of the most successful authors in history. On the 30th anniversary of It (1986), a book that arguably encapsulates all of King’s core themes, Adrian Daub talks about what the book meant to him, despite growing up on the other side of the planet.

The Parallax View, Michael Thomson, Real Life

Videogames aren’t the first medium to strive for realism, but what that means for virtual reality is a sentence to endless hyperreality. Beyond the uncanny valley, Michael Thompson writes about the faults of abstracting our world through a blender into another, the redundancy of only appearing real.

Photo provided by Norm Macdonald to The New Yorker

My Greatest Gig, Norm Macdonald, The New Yorker

An ideal world is one that’s just a bunch of Norm Macdonald’s anecdotes about the comedy world. In one step towards that utopia, he has released a memoir, Based on a True Story, filled with truths, half-truths, and flat out lies. The New Yorker has released an excerpt so you can spend at least a few minutes in this hypothetical better world.

The Creepiest Series On YouTube, Daniel Oberhaus, The Awl

I know, I know: what “Creepiest Series On YouTube” isn’t the “Creepiest Series On YouTube?” But with as much walk as talk, Daniel Oberhaus explores the making of “Marble Hornets,” a branching gothic tale born online that threaded itself into the web we now know as the creepypasta phenomenon.

The post Weekend Reading: Real Funny, Scary Funny, Real Scary appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 23, 2016

Screw you Destiny, I will hug all of your dogs

This is an open letter to Lord Saladin—more like Lord Sala-didn’t think I was going to complain about your dumb dog rules, eh? Joke’s on you.

You’re tired. Lord Saladin looms over you while recanting old tales of the Iron Lords. The push against The Fallen was long and gruesome. You made it out alive with only a few dings in your gear, signifying that the battle was a modest success. Expectations of relaxing after the raid were thrown out the window as soon as you saw the wolf-man himself, awaiting your return. In your head, you think: Lord Sala-didn’t know when to quit talking. He stops pacing back and forth and looks down at you. “No one truly knows how the Iron Lords died their final deaths. That was something you had to be there for.”

Wolves are just bigger boys

You liked to think that you were listening to him the entire time but, truth be told, you were too busy staring at the two beautiful wolf-dogs sitting obediently on either side of Lord Sala-don’t touch my dogs. They were massive, muscular canines with sharp teeth and keen eyes—more importantly, they were good boys. They were good boys that deserved to be pat on the head. Lord Saladin catches the yearnful gaze you cast upon his wolves and he frowned disapprovingly. “You cannot pet the wolves,” he tells you. “They are not pets. They are wild animals.”

Destiny: Rise of Iron was released on September 20th, boasting a new story campaign followed by gear and wearables. A new Crucible mode is included as well. There’s a lot of new content for players, but one important gesture seems to have been overlooked. Where is press A to pet dog? A recurring theme among Rise of Iron seems to be that Bungie emphasizes that the wolves inside the game cannot be interacted with. Your heart breaks for the good boys of Destiny.

Are not all good boys entitled to pets? If they fit the criteria of a good boy, then they deserve to be treated like the best of boys. Is a wolf not entitled to have the fur on his back fluffed up by a gentle, loving hand? Would Lord Saladin deny a dog the crooning of “who’s a good boy?” into their perky ears? How else are they supposed to know that the Iron Lords appreciate them if we are not allowed to throw ourselves at the four-legged fantastic beasts? Wolves are just bigger boys. Let us pet them, Lord Saladin.

Are not all good boys entitled to pets?

You get up and gesture to your armor—overtop the chainmail protecting your body is a giant chestpiece with a wolf silhouette that is literally on fire. Resting on your shoulders are two massive wolf heads crafted from metal, mouths ajar with a tongue made of fire and eyes burning with the red-hot desire to pet some dogs. Lord Saladin gazes upon your armor and shakes his head. “They are wild animals,” he repeats. He turns on his heel and begins to walk away from you.

Photo by Brian Malkiewicz

But there are dog-petting loopholes before you. If you walk up to a wolf and have the correct emote in front of him, you can hug him. You may not be able to pet the good boys of Destiny, but you can doggone try.

Photos of dogs provided by Gareth Damian Martin

The post Screw you Destiny, I will hug all of your dogs appeared first on Kill Screen.

Astroneer will take humanity’s fight against nature to space

In last year’s man vs. nature (in space) thriller The Martian, Matt Damon’s stranded botanist looks into the camera and tells us exactly how grave his situation is. “If the oxygenator breaks down, I’ll suffocate. If the water reclaimer breaks down, I’ll die of thirst. If the Hab breaches, I’ll just kind of implode. If none of those things happen, I’ll eventually run out of food and starve to death…”

Aside from establishing those desperate stakes, that quote makes it very clear that, for the humans that step foot on another surface far from Earth, the most pressing danger isn’t going to be malevolent extraterrestrials or rampaging AIs. It’s going to be the planet itself, that brutal combination of inhospitable landscape and incompatible atmosphere. System Era’s upcoming Astroneer seems to take that quote to heart. Forget about combat or aliens to kill. Here, the environment is your enemy.

Creator Jacob Liechty explored this focus on environmental danger rather aggressively in a reply on Reddit. “Not having monsters to shoot does pose a problem for us, but by no means one that’s unsolvable. The basic ‘monster loop’ is something like: Encounter threat, Expend time and resources to resolve threat, Learn from experience and repeat. There’s no reason you can’t have this without monsters, and environmental dangers have the advantage that they’re true to life. The only disadvantage from a design perspective is that environments don’t chase you (at least not on purpose).”

you overcome the blinding dust and wind

In Astroneer, that monster loop is replaced by a need to adapt to and survive a hostile landscape, where dust storms, starvation, and unstable terrain are as fatal to you as any alien beast would be. Jacob continues, “But we are hard pressed to think that, when we read about actual space missions and when we watch reality-grounded sci-fi in which there are no aliens, that there still isn’t a really fun game there. The threat loop isn’t going to be as explicit as a bullseye, but like you say there are far more interesting problems the player will run into (repair, resource management, planning) which are equally life-and-death.”

But to the smart explorer following those tenets of planning and management, the deadly environment can help and hinder in equal measures. The unstable terrain that threatens to cave in while you dig through subterranean caverns can also be used to form barriers and shelters against approaching storms. Those fierce gales that can scatter your valuable bases and vehicles are also a potential sources of energy through wind turbines.

Conquering the game’s many planets through science and engineering is perhaps Astroneer‘s most central idea. Through tethers and guidelines, you overcome the blinding dust and wind. Through rovers and jeeps, you conquer the sheer size of the game’s sprawling planets. And through automated railways and drilling mines, you make that hostile landscape work for you, gathering the materials and minerals needed to build spacecraft to travel across the solar system and discover its secrets.

Astroneer is coming to Steam Early Access and Xbox Game Preview in December. You can learn more about the game and find additional screenshots on System Era’s blog, Twitter, and Facebook page.

The post Astroneer will take humanity’s fight against nature to space appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers