Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 48

September 30, 2016

Danny Brown will die for this shit

“On death row, feel like I am…”

For Danny Brown, all is lost.

Atrocity Exhibition is the most heartbreaking record in a minute. It begins, quite literally and awash in scuzz, with the “Downward Spiral,” an ongoing theme in Danny’s work since 2011’s seminal XXX. Herein: Danny, on a coke binge, contracting STDs, allowing his own exploitation, in a clown car, a circus show, the atrocity exhibition; this idea that Ballard and then Curtis put forth years ago, and Brown somehow has the intuition to put back in the forefront of our minds at this present time.

The freak show that is mankind, abusers and the abused, all captured by the legion of recording devices that are now on the streets, in everyone’s room, in every nook and corner of our society, that are the all-seeing filters through which we now view anything and everything. Streaming, Instagrammed, Tweeted, cheap—discussed glibly and then linked. Our lives are now parceled to us as entertainment, distraction from current ills and dawning ruin. The ills and the ruin, themselves, packaged back to us as amusement—our subscribed stimuli and our words and actions writhing themselves into a gruesome ouroboros. In the face of endless injustice, selfishness, and wrongs, “Tell Me What I Don’t Know” is Danny’s litany.

Danny slays, slays, slays

Danny uses this feedback loop as mirror and haunting personal slide show, leering sadly at his present and his past (the future unknown, but indubitably wrecked). The cover of Atrocity Exhibition is like a bad video recording crossing signals with an x-ray. Danny invites us, in his self-exploitation, to go deeper while staying on that same surface level, to superimpose the two. It’s how Atrocity Exhibition can be a record that’s essentially all about trauma propagating debasement, loneliness, disintegration (“Riding around with the windows up / Smoking like it’s ten of us / Just me in the back seat”) … and yet feel so fire, knock so hard, bang its way into your headspace. What this accomplishes isn’t just impressive, but chilling. We want the flesh but we want the guts, too, it reveals. We’ve become the most ravenous of cannibals. “Merci, Danny, for giving us what we ordered,” we lip-smack as we tuck our napkins in, and “bon appetit” Danny seems to nod back, grinning with dead eyes, splayed out upon our plates.

“Even if she fuck me / I still know life a bitch / Bought a nightmare, sold a dream…”

Danny lives his life by self-destructing (“Pneumonia”), then self-medicating (“Get Hi”), walking a tight rope of both fearing death and consuming it—depicted with devastating clarity on the certifiable “White Lines”. The nine-song stretch of the opener on through “Pneumonia” is fierce and flawless, sonic and verbal slaughter. It builds from setting the stage with dystopic bangers (none bang-ier than the twinkling, churning epic that is posse cut “Really Doe”) to inverting into its absolutely gutter middle section, “Lost” through “Pneumonia” showing Brown chomping, choking down his excess—then regurgitating, feasting again. The beats seem queasy at the sight. “Ain’t It Funny” is the record’s simultaneous peak and valley. It sounds sickly triumphant, like it knows it is celebrating its own demise, as Danny slays, slays, slays …

“Nose bleeds red carpets / But it just blends in / Snappin’ pictures / Feeling my chest sunk in.”

The record becomes random and fractured after “Pneumonia,” replete with rave, trap, boom-bap, and the best Wiz Khalifa song ever in “Get Hi,” bouncing between them all with no semblance of sense, since Danny seems to take a sudden turn and intentionally rejects the idea of trying to craft a masterpiece that’s hermetic. For the listener, this can be off-putting. But for Danny Brown, it’s real. There is no such thing as “picking up the pieces” of his life or identity or artistry. He lets them lay where they fall, broken, bound to the ground by hell’s gravity. Every song is punched through and hung upon the same bitter through-line. Even directional molly-popper “Dance in the Water” confounds, as its most impossible-to-follow command is the one that Danny emphasizes and repeats: “Dance in the water / and not get wet.” A strange ache enters the party.

He’s sending us singing telegrams from the living underworld

Musically, the record remains audacious and unhinged throughout, but it would be as wrong to claim this is something new as it would be to try to contextualize this record or Danny in terms of other records or rappers. Because Atrocity Exhibition, like Danny, is something wholly singular, but it is always speaking in languages we’re familiar with, for it needs us to feel it. Primarily, it’s speaking the language of rap and the language of pain. It’s on closer “Hell For It” that Danny pulls back the curtains one last time. It’s like an encore of him alone at a keyboard, spitting bars with a serene acceptance of his lot. The creases in his face soften. He tells himself that he’s “the greatest alive.” He tells us that this was all for us.

“I lived through that shit / so you don’t have to go through it / Stepping stones in my life / Hot coals / Walk with me / Listen when I speak / Every time talk with me / Couple screws loose / You don’t want to start / with me.”

All is not lost for you and me, or at least that’s what Danny prays. He’s sending us singing telegrams from the living underworld, warnings. The fire that is this record isn’t just a visceral thing, it belongs to perdition. The tears that Danny cries aren’t just self-pitying, they’re benevolent (even as he’s “wishing that it rain” to mask them). How can a rap record this goddamn hard also be so intent on leaving us behind in the hands of grace, pushing us up as it falls? Danny seals his fate to keep the ice from cracking underneath us. We watch him sink as the ground turns glass, for us to watch the exhibit. The life that he never really glamorized, well, on Atrocity Exhibition he embraces it to betray it.

“Holy Spirit / When I look / I cannot see / reflection in the mirror / Broke bread with the Judas / and I think I see it clearer.”

To paraphrase Hamlet, the play’s the thing that captures our conscience. The ferocity of Danny Brown’s nasty art should repulse us, but instead it draws us in and owns us because of the way in which he delivers it—for our entertainment. More than that, it’s ugliness as beatitude, poetry of filth. Because of this, we Danny Brown fans care more about Danny than we even care about a lot of people that we actually know. We see Danny’s humanity, we hear his illness, we fear for his future, and we nod our heads to these beats and his irrepressible flow, laugh-crying at his punchlines. Because he lets us. If only we could have the same level of empathy for everyone without needing the exhibition, maybe atrocities would cease.

But that would not be the “cold, cold world” that Danny knows, that he details for us in lurid rhyme. So we need the atrocity exhibition to make us feel past the numbness, and we need it to numb ourselves when we can’t let ourselves feel the pain closest to us. But most of all, we need it to know something of what Danny knows, so that we won’t be forsaken like him. We need it to purge us from what makes us like him, to keep from getting caught in the loop that Danny’s fed and feeding, as the serpent eats its tail. We need something to be destroyed and for that to be shown to us, in order for us to have eyes that see, ears that hear.

This is why the world needed a Judas. This is why we need Danny Brown.

His truth is marching on; it’s the downward spiral.

The post Danny Brown will die for this shit appeared first on Kill Screen.

Dear Esther: Landmark Edition is a delicate, embalmed object

Heterotopias is a series of visual investigations into virtual spaces performed by artist and writer Gareth Damian Martin.

///

Videogames have always had something of a preference for islands. These closed spaces, limited by a shoreline, are the perfect conceit for creating an enclosed simulation—an isolated section of “reality” split off from the world. Despite this, thematically, games rarely have anything to say about their own predisposition towards landscapes of isolation, separation, and abandonment.

For Dear Esther, these are central themes. It’s easy to imagine that Dan Pinchbeck’s choice of an island setting for the original 2008 Half-Life 2 mod, built as part of a project at the University of Plymouth, was motivated by technical and practical reasons. But the island of Dear Esther seems to have quickly become a symbol for the game itself. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that an academic project would be so self-aware, but it is the delicacy of this self awareness that stands out.

Briscoe preserves Dear Esther‘s artistry rather than muddying it

When level artist Rob Briscoe took on a graphical conversion of Dear Esther in 2009, he brought a further layer of delicacy to its world. The resulting 2012 version demonstrated a mastery of light and form, its journey through a series of rhythmical spaces scored by the careful direction of Jessica Curry’s music and the reassuring warmth of Nigel Carrington’s voice. It became a cultural island all of its own, a small but beautifully formed experiment that carefully laid out a piece of previously unexplored territory from pieces borrowed from the storied past of first-person games, and stripped everything but tone, emotion, and form.

This year’s Dear Esther: Landmark Edition, surely the final form, is an equally restrained affair. Briscoe has returned to shift the 2012 version from the Source Engine to Unity, resisting the temptation to “visually upgrade” the game in any way. It’s a laudable approach, and one that it would be good to see repeated elsewhere. By doing this, Briscoe preserves Dear Esther‘s artistry rather than muddying it. The result is a wonderfully imperfect recreation of a vital cultural object.

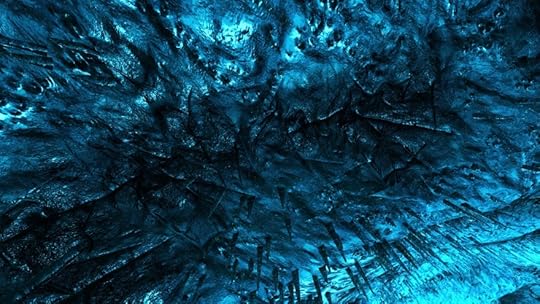

That sense of Dear Esther as a cultural object, not a world or “alternate reality,” stuck with me as I returned to it for this column. In particular I found myself recognizing the traces of Valve’s Source Engine that lay across its world. Briscoe admits that the game’s aesthetic and level structure was shaped by the engine’s limits and strengths, but even without his recognition of this, it is self evident in the game. The soft, flat light of the world, the tendency towards detailed, almost pointillist texturing, even the choice of props which was guided by Pinchbeck’s original selective use of existing Source assets. That’s the strange thing about Dear Esther; that in many ways it does not more than passingly resemble a Hebridean island. It’s something that perhaps can only be picked up if you have, like me, spent much of your childhood on the windswept islands of Scotland. It’s in the geology, the plants, the sand, in a thousand tiny details that feel disjointed from my memories and images of Eigg, Mull, Skye, and the scattered pieces of Orkney.

This is not a critique of the game’s accuracy, but more a recognition of how it is as much a representation of a game engine and its aesthetics as it is an analog of a real location in the world. For this reason, over this new playthrough, I found myself increasingly disinterested in capturing the beautifully arranged landscapes the game reveals to you, and instead fascinated by the digital material of this object world. I was drawn to limited details, distorted textures, to the pointillist approach to color that leads to the somehow both saturated and drained look of the game. This feeling of awareness became entwined with the game’s own fictional self-awareness; the overt suggestion that the island is a figment of the character’s imagination, a psychological purgatory they must endure.

I found significance in the pixelated corpse of a seabird

I started to think of the textures, the distortions, the limits of the engine as analogous to the character’s limited imagination. As if this dead, digital island was an object brought to life by a mind in mourning. I found significance in the pixelated corpse of a seabird, in the trash jammed into a sand texture, in the constant reminders of the limits of this island. Might the game’s secrets be hidden in the way one polygonal plane joins another? In the flat detailing on a supposedly natural surface, that reveals itself to be entirely digital?

That might sound absurd, and yet I suspect there is more truth to it than we imagine. Games are objects, and their material makeup matters. By preserving, not transforming Dear Esther, this edition brings that into focus.

What follows then is a record of the pieces that make up the whole. The persevered, embalmed details of this exquisite corpse.

The post Dear Esther: Landmark Edition is a delicate, embalmed object appeared first on Kill Screen.

Growbot gets its adorable look from children’s books of the past

Children’s books used to have a more strange, haunting quality; think Wayne Anderson’s Ratsmagic (1976) and The Magic Circus (1978). Books had a sense of darkness, and not every tale was meant to be safe and moralizing. Growbot, an upcoming 2D point-and-click puzzle adventure, is a game that evokes the strangeness of Anderson‘s classics. Created by illustrator Lisa Evans, it’s a game that draws from classic children’s book through its art and narrative.

“These kinds of narratives are rarer in the [children’s book] industry these days, because in order to get in front of an audience you need to go through the gatekeepers of the publishing industry,” Evans said. Games, in comparison, allow for some experimentation. She attributes this to programs like Steam Greenlight. “It seems to lead to much more diversity in stories and experiences than children’s books currently enjoy.”

Growbot is about Nara’s terrible first day at school. She’s a student on-board a space station when an unknown force attacks the ship, cutting off communication with rapidly growing crystals. Not good! Playing as Nara, you’ll have to search the space station for help, solving puzzles to fix the station’s wacky and weird equipment while figuring out where this crystalline force came from. So while it’s a narrative game, puzzles will push the story forward—a feature that’s new for Evans. This is her first videogame. “I wanted to push myself further out of my comfort zone and think about the player’s experience in terms of the verbs they can use to interact with the world,” Evans said. “It’s also another way of bringing the world’s I like to imagine to life, helping to pull players into the world.”

“In a game, you have to justify your ideas more”

Tove Jansson’s Moomin books are an influence in Evans’s career; particularly, the idea that Jansson’s books have “a world where bad things happen not to be corrected by the heroes, but as a simple fact of life.” The dramatic problems in the Moomin books tend to be less about villains, and more about natural disaster—”floods, comets, or a long winter,” Evans said. For Growbot, that natural influence is the mysterious crystal entity consuming the space station.

Creating a world with depth has been a challenge for Evans—albeit, a good challenge. “Making a game has been way harder than building a book,” she said. “If I want to create a piece of strange machinery in a book, I can draw it without thinking too much about it and the viewer is free to imagine its function.” It’s different in games, though, of course. “In a game, you have to justify your ideas more,” Evans added. “The machinery should have a purpose and the player should be able to do something with it that changes the environment.” The Unity engine, in that way, has been helpful in regards to creating those systems—in particular, the Adventure Creator plugin. Evans started the process of creating Growbot without needing to code, though she’s picked that up on the way, too.

Growbot is currently in its voting period on Steam Greenlight. Follow its progress on the official website or on Twitter.

The post Growbot gets its adorable look from children’s books of the past appeared first on Kill Screen.

Honey Rose is the most relatable schoolgirl luchador out there

I relate a lot to Honey Rose. Or, at least I did back when I was a scrappy university student. While Honey moonlights as a masked luchador fighter in addition to being a college student by day, I juggled school, a job to pay the bills, and a far more time-consuming job that paid zero bills (campus publication editor gigs will do that to you). Like Honey, not everything went right. Sometimes I did poorly on tests because a deadline was approaching for the magazine I was art director for. Other times I’d slack off in one of those two, because I had to work long hours to make rent. University was hell, basically. I always wished I had more hours in the day. And frankly, Honey probably wishes for that too.

Honey Rose, or “Red” as she’s referred to outside of her masked moniker, is the star of the new visual novel life simulator beat ‘em up hybrid called Honey Rose: Underdog Fighter Extraordinaire. The game is what you’d expect out of the life simulator genre, wherein you manage a person’s life to make sure they succeed. Except for when the game throws curveballs to put your routine out of whack (plus the whole lucha libre fighting aspect I guess, which is easily a first time addition for the genre).

Instances where life surprises you made the game feel relatable

In one particular instance, I directed Honey to train with her coach because her defense meter dipped, only to be mugged and have my suit stolen along the way. My spare time after that was shifted to studying and, well, finding Honey’s lost suit. Luckily I got it back a day or so later after throwing a few punches. It was instances like that where life surprises you (and fucks up your day) that I felt the game be the most relatable.

But then the unrelatable stuff kicks in, or at least unrelatable in the literal sense (not the “I have too much to do” way). What sets Honey Rose apart from other life simulators is its beat-’em-up components. I mean, you are playing as the conscience of a secret luchador fighter after all. Fighting in (and sometimes out of) the ring is bare enough. There’s grapples and dive kicks, with some special moves thrown in. Choosing to play the game on a keyboard, however, seemed to doom me in the fighting portions. Or maybe I’m just bad at fighting games. It’s probably more the latter than the former. Alas, I almost wish that the fighting was dumbed down a bit more, being that despite training frequently, I lost more fights than I won. But maybe that’s the punishment I deserve for choosing the middle-tiered difficulty in the opening, rather than the beginner, story-focused mode.

Despite being touted as a visual novel, I found the visual novel portions of the game to be the least enticing. While I enjoyed Honey Rose as a tough-as-nails, determined character, I never found the stories surrounding her to be particularly interesting. I appreciated the diverse cast (consisting mostly of women and people of color), but they never expressed personalities that I was dying to get to know better. So I was shitty, and blew off hanging out sometimes because I felt like keeping my stats balanced was more important. For a visual novel, the actual reading was a chore. And that’s a bummer.

failure is the omnipresent enemy

There aren’t any numbers on the meters in Honey Rose, making cataloging how well you’re doing in school subjects and fighting stats-building a struggle. This is intentional, meant to actually mimic how tenuous progress in real life is. Unfortunately, I found the lack of progress-tracking to be more annoying than immersive. I ended up longing for the experience I found in games like the Persona series, whose meters made later decision making a much easier—and enjoyable—process. Where balancing life was still a difficult, engaging task, but felt more worthwhile because I had an end goal in sight. Honey Rose negates this for realism’s sake, which I can’t help but commend, even if it hurts the game’s mechanics.

On the surface, I found Honey Rose similar to other life simulators like Long Live the Queen (2012), which was actually an influence according to the game’s creator Pierre Sylvain. In Long Live the Queen, merely living to being crowned queen was the primary goal, but death snakes its way in as a looming presence. In Honey Rose, failure is the omnipresent enemy. And the road to succeed is never easy.

Overall, I enjoyed Honey Rose. Its animated art style makes it look often like a lo-fi cartoon, rather than any ol’ videogame. Its style is unmatched in the life simulator genre—which mostly consists of anime and manga-inspired art. While the in-game fighting wasn’t fun to engage with and the characters a wee bit bland, it’s overall a worthwhile game to check out. And hey, hopefully we see more creative hybrids like this starring diverse casts in the future. I’m always down for more laid back games about stressed-out young adults chasing their dreams, because that’s me. Right now. Here. I like seeing myself in games, and I’m sure you do too.

Honey Rose: Underdog Fighter Extraordinaire is available now on itch.io and Steam per a Pay-What-You-Liked model. To download and play initially it’s free, and if you liked it, you can toss the creator a few buckeroos (which is the decent thing to do, in my humble opinion).

The post Honey Rose is the most relatable schoolgirl luchador out there appeared first on Kill Screen.

Play Kentucky Route Zero now, before it’s too late

“More mysteries. They do pile up, over time, as people forget the details.”

-Shannon Marquez, Kentucky Route Zero Act IV

Kentucky Route Zero is defined by its voids. From its haunting, shadowy landscapes to its characters’ featureless faces, the meditative, five-part digital stage play offers players plenty of empty spaces to fill in or leave blank at their discretion. The increasingly large gaps between the releases of each new chapter of the still-in-development story are another kind of void. We only just got Act IV after an 18-month wait, which means that at the current exponential rate, the final act won’t show up until late 2020. Intentionally or not, these tremendous expanses between releases have come to define Kentucky Route Zero as much as any individual aesthetic choice. And though many players are eager to jump from one act right into the next, these waiting periods have forced restraint and opened up an experience with Kentucky Route Zero’s world that can’t be replicated by bingeing through it.

Kentucky Route Zero isn’t simply an impeccably written, visually resplendent game that begs to be played, it’s an impeccably written, visually resplendent game that, ideally, should be played right now. As with many episodic games, there are those players who are holding off on starting Kentucky Route Zero until Act V drops and the entire series is available all at once. However, in doing so, players will miss out on the game’s abundant voids, some of which cannot be duplicated from their original contexts. These voids are where Kentucky Route Zero seeps into the real world, floating between foggy memories of past events to create a game experience that you’re actively “playing” even when you’re not.

For starters, the gaps between Kentucky Route Zero releases help establish a contemplative pace for the episodes themselves. Each act lasts a mere one-to-two hours, and then it’s over. Every aspect of Kentucky Route Zero pushes players to savor it. You’ve heard of “slow food?” Well, this is “slow games.” There’s very little actively driving Kentucky Route Zero forward beyond podunk curiosity. Act IV makes this more apparent than ever, as players spend most of the episode drifting along the currents of the Echo, a subterranean river, making leisurely stops for small talk to flesh out the offbeat nuance of everyday spelunkers. On multiple occasions, characters will refer to the pace of life on the Echo as operating on “river time.” Which is to say, things happen when they happen. This is not too far off from developer Cardboard Computer’s mantra of “we’re getting there, thanks for your patience” in response to pleas for new chapters of the magical-realist saga. The team avoids hyping their releases with advance launch dates, instead preferring to unceremoniously drop chapters and interludes in players’ laps without warning beyond the occasional “soon.”

“what if Kentucky Route Zero wasn’t only a videogame?”

To be a Kentucky Route Zero player is to embody the spirit of “river time,” both inside and outside of the game. Every episode of Kentucky Route Zero is full of dialog options for players to select and direct the way the story fleshes out. Unlike the Telltale Games model for player choice where the difference between option one and two can be life or death, Kentucky Route Zero’s options are more concerned with establishing backstory or offering subtle tonal variations on character responses. How self-conscious is Johnny about talking aloud to a dog? Would it be too awkward for Shannon to point out the irony of Conway’s fatalist demeanor? The consequences don’t so much steer the plot as define what kinds of people the characters are. Players don’t control the current, but they can decide on which side of the boat to lounge.

More than anything though, the gaps between Kentucky Route Zero acts allow players to forget certain details from previous entries. “Forgetting” is a notion that’s utterly counterintuitive in most games, but serves the atmosphere and play experience of Kentucky Route Zero so well. The world of Kentucky Route Zero is one of clouded obfuscation. Flashlight beams stall in the dark and static mucks up telephone wires and TV antennas alike. Characters are reluctant to reveal their true feelings and motivations, leaving players to piece together fragmented anecdotes with surreal allegories. And, in general, there’s a lot of drinking and whiskey talk. The results are impressionist portraits that ask more questions than they answer. There are no “previously on Kentucky Route Zero” recaps at the start of each act. The game might be episodic, but it’s not trying to be television. A hazy recollection of past events is fitting, and leads to players feeling a bit like drifters themselves.

It’s a neat trick, and leads to each new act feeling like players are bumping into characters in an old tavern ala Act III’s The Lower Depths. Players get reacquainted with everyone in turn—some of the faces they recognize more than others. “Don’t I know you from somewhere?” “Ah, still making deliveries?” “Oh, you know Weaver?” The two musician characters, Junebug and Johnny, make robotic squeaking noises when they walk. Are they androids? I don’t know, but I’m content to maintain my suspicions via side-eye glances rather than look it up in a Wiki. And the dialog choices that emphasize player performance over plot direction support that approach.

The real payoff from the waiting periods between acts isn’t the delayed gratification of each new episode, but that the voids themselves—dotted with interludes and experiments—have become staging areas for a Kentucky Route Zero alternate reality game (ARG), where virtual and real worlds merge as one. Released between Acts I and II, the first interlude, Limits and Demonstrations, features an art gallery exhibition, filled with intricate media art installations of fictional character, Lula Chamberlain. 10 months later, Cardboard Computer staged a real version of the retrospective at the Little Berlin gallery in Philadelphia, complete with the backstory that artist Lula Chamberlain was a little-known contemporary of John Cage and Nam June Paik. The show was on view for a mere four days, meaning that if you weren’t actively “playing along,” you’d miss an aspect of Kentucky Route Zero as live performance, even if you couldn’t personally attend the gallery reception.

can’t be replicated by bingeing through it

For Here And There Along The Echo, which preceded Act IV, Cardboard Computer recorded an automated tourist information hotline for the Echo River that players could call with an actual telephone. The result is a Welcome To Night Vale-esque trip down a bizarre rabbit hole of quirky tall tales couched within the banal framework of a national park hotline. Additionally, Cardboard Computer held several auctions for physical telephones (one done up like a local cable access special) that, according to the item descriptions, could only dial one number. Because of these weird tangents where Kentucky Route Zero’s digital world seeps into our own, what happens between episodes sparks as much intrigue as the episodes themselves.

All of this mixed reality scene setting makes even (admittedly rare) social media updates from Cardboard Computer feel less like marketing materials and more like a slow drip of found footage that has been unearthed. It’s as if the Kentucky Route Zero we know is actually an archaeological excavation of a world removed from yet parallel to ours, cognizant of the passage of time. A single screenshot is tweeted without context. Rotatable digital vignettes offer a fragmented glimpse of what might await players just under the surface. A fictional cable-access channel announces new music from Junebug with a live studio performance. Sure, this requires suspension of disbelief to become invested, but unlike most ARGs where it feels like the designers have pulled the wool over players’ eyes, Kentucky Route Zero leads with its outwardly fictional videogame premise. And while the endpoint of playing most ARGs is to dispel the truth behind the illusion, Kentucky Route Zero poses the more playful question, “what if Kentucky Route Zero wasn’t only a videogame?” It’s an intellectual query that holds far more weight in the here and now than in retrospect.

The post Play Kentucky Route Zero now, before it’s too late appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 29, 2016

Girl Scouts can earn videogame design patches now

It’s hard to turn down a Girl Scout, and that’s no accident—I should know, I am one. From the start, we learn valuable business and communication skills through selling cookies (that are, objectively, pretty damn good). Community service often has an emphasis on sustainability and environmental justice, meaning our projects will continue to have an impact long after they’re over. Workshops and field trips allow us to explore new interests in a safe, encouraging environment. We do all this hand-in-hand with our own girl gang. The end result? Girl Scouts are fearless. With the encouragement of STEM programs, they’ll be unstoppable.

there’s a dire need for more women making videogames

PlayStation’s Santa Monica Studio is teaming up with Women In Games International (WIGI) and Girl Scouts of Greater Los Angeles (GSGLA) to provide a workshop for aspiring game makers to learn what it’s like to work in videogames. Aspiring designers will create a physical prototype, digital prototype, and test their design under the watchful eye of the Santa Monica team. While currently only available in LA, the program is part of a larger initiative to offer a nationally recognized videogame badge.

The program couldn’t be more timely: as organizations like Girls Make Games and Feminist Frequency have stressed, there’s a dire need for more women making videogames. According to the Entertainment Software Association, women make up 48 percent of those who play games, but only 12 percent of the people who make games are women. The conversation about women’s representation in videogames is divisive, to say the least—that’s why Girl Scouts proclaiming that “Girls are natural born scientists!” on their Women in STEM page feels like a breath of fresh air.

Game development is the latest in a long list of STEM-related activities for which girls can earn badges. Some of the other categories for badge programs include Naturalist, Digital Art, Science and Technology, Innovation, and Financial Literacy. Studies run by Girl Scouts of America have shown that girls gain confidence and problem-solving skills after participating in their STEM programs. Encouraging girls to explore STEM is crucial—more than three quarters of female high schoolers are interested in pursuing a science-related career, yet women hold only 20 percent of computer science, physics, and engineering degrees.

Looking back on it, Girl Scouts was one of the better things I did with my life. I learned how to market myself, and ask for what I want. I sold cookies. I changed lives. With luck, the resources made available by Girl Scouts and related organizations will empower girls to do the same—and continue going boldly where they’ve never gone before.

h/t Wired

The post Girl Scouts can earn videogame design patches now appeared first on Kill Screen.

Just what the Trojan War needed: a huge, explosive gun

The Trojan War is a comedy and a tragedy, a series of deaths that history will remember by its errors rather its feats. When they teach the Trojan War, they talk about a beautiful woman whose face was enough for an armada to be launched and a large wooden horse that defeated an impregnable city.

When Atlanta-based game maker cottontrek talks about the Trojan War, they do so in a series of explosions.

Explojan Horse is not a game of subtlety. Constructed over a weekend for the latest incarnation of the Ludum Dare game jam, Explojan Horse is a cross between “an easily recognizable aspect of the classical era of history” and the historical comedies of Monty Python. These are not the battles of great men, constructors of a large trophy and trap, but rather some dudes with a really big gun.

The Trojan War was bloody, as most wars are, especially ancient ones. Homer describes in his epic a battle that is both richly detailed and violent: as a man is “he was run through with a pike in the soft bit below the jaw, and was dragged behind the chariot flopping like a fish caught on a fisher’s line.” Perhaps cottontrek’s over exuberant explosions are not too far off the mark.

You can find cottontrek’s full game Explojan Horse on itch.io.

The post Just what the Trojan War needed: a huge, explosive gun appeared first on Kill Screen.

All bow down before the mighty Shin Godzilla

At one point in Shin Godzilla, Toho’s 29th entry in this ancient series, a character calls Godzilla a “perfect organism.” This might sound familiar to anyone who’s watched Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979): it’s how the devious android Ash describes the xenomorph.

Godzilla movies don’t typically reach outside the big guy’s cultural bubble, the occasional crossover with King Kong notwithstanding. They exist within a cloistered half-century of constant reinvention; there are whole eras of Godzilla named for whoever was emperor of Japan at that time, all refracting and, frankly, diluting the original premise into a repeatable formula that yielded enjoyable-but-inessential riffs on everything from pulp sci-fi to spy thrillers.

It is with pleasure that I can report that the upcoming Shin Godzilla, which translates roughly to “New” or “True Godzilla,” is the first Godzilla movie since Gojira (1954) to feel relevant to contemporary issues—assuming you don’t count Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster (1971) as a trenchant critique of wanton pollution.

Also, hey, it’s extremely good. Co-directed by Neon Genesis Evangelion creator Hideaki Anno and Evangelion assistant director Shinji Higuchi, and written by Anno himself, Shin Godzilla reconfigures the kaiju film as a satirical kaleidoscope of bureaucratic bullshit. “Open fire” orders have to run through 15 people before the Prime Minister can give his OK. Conferences on conferences are held to determine what Godzilla is or isn’t. Rapid response teams come together and collapse just as quickly.

Anno’s script doesn’t have characters, just recurring faces as it follows the Japanese government’s frantic attempts to deal with the appearance of Godzilla in Tokyo Bay. Every single person repeatedly gets their title splayed onscreen in massive kanji. Every location and makeshift HQ gets the same thing, growing ever-more complicated as the situation worsens.

the single most glorious version of atomic breath yet put onscreen

This becomes a running joke, a self-reflexive commentary on what we’re seeing: two men argue whether under the Constitution, Japan can ask the US to just take Godzilla out for them. As they argue, the entire text of the articles they’re referencing is superimposed over arch low-angle shots of their faces.

Anno and Higuchi find innumerable ways to make a film that’s 75 percent stern Japanese men bloviating in office spaces visually interesting and witty, from smash-cut punchlines to a surprisingly goofy “first form” for the big guy himself. The destruction—very satisfying, very cataclysmic—is similar to their “Giant God Warrior Appears in Tokyo,” a short prequel to/adaptation of Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984).

About halfway through, the film twists into something darker. If Gojira was a response to the atomic bombings, Shin Godzilla speaks to current anxieties: the Fukushima meltdown, Japan’s place in an aggressively militarized modern world. There is a lot of Evangelion DNA in here, to no one’s surprise. Godzilla is less a giant reptile and more a massive fleshy pupa, undergoing a rather xenomorphic life cycle. It’s got weird eyes, a habit of spewing gore out of its gills (it’s got gills in this one, roll with it), and the single most glorious version of atomic breath yet put onscreen; a sort of vomitous disco ball of destructive energy.

It ends, as a Godzilla movie must, inconclusively: the beast is merely paused and the final recourse of nuclear response along with it. The final image is sequel bait that makes no sense at all. All it promises is an even weirder follow-up, one rife with the Biblical phantasmagoria that Anno made his contentious reputation on. Trust no one about this movie, not even me. See it for yourself—prostrate yourself before the one true Godzilla.

Shin Godzilla was released in Japan on July 29th. It will get one-week limited release in the United States and Canada from October 11–18.

The post All bow down before the mighty Shin Godzilla appeared first on Kill Screen.

Duelyst brings collectible card games back down to earth

J.K. Rowling was remarkably creative when coming up with Wizard’s Chess. A favorite pastime of Ron and Harry’s in the early Harry Potter books, wizarding chess is exactly like regular chess, except the pieces move by themselves and smash one another when taking opposing squares. “That’s totally barbaric,” opines Hermione in the first film. “That’s Wizard’s Chess,” responds Ron, as if pitching the game to a room full of Hasbro execs.

As evidenced by Duelyst, though, the gimmick is surprisingly effective. The first thing anyone will notice about Counterplay Games’s tactical RPG, collectible card game (CCG) hybrid is its irresistible pixel animations. All thanks for those should go to artist Glauber Kotaki, best known previously for his work on Rogue Legacy (2013), and the not-yet-released Chasm. His style is vibrant and kinetic, and no doubt a large part of what made Duelyst‘s original Kickstarter campaign such a success. Compared to the game’s more static analogues, from Hearthstone (2014) to chess, a graphical hustle motivates every individual unit and spell with casual grace.

Imagine a digital bucket filled with beautiful little toys that move and breathe and stab at your command, one series of colorful splashes after another. First you decide which bucket you’re going to play with in the form of a general and its corresponding faction—will it be a knight who can buff nearby units or a ninja that can teleport them? Then you decide which units, spells, and artifacts to fill the bucket with. Are a handful of late-game golems preferable to an army of weak, early-game wisps? Finally, you go and spill them onto a grid-lined battlefield against an opponent to see whose general can smash the other’s first. Defeats are hard-fought and victories feel more narrow

For all of the things Duelyst borrows from Hearthstone, including its free-to-play progression system wherein players can earn new cards by grinding out victories or pay for new packs with microtransactions, the use of a board with 2D movement transforms it into something fundamentally different. Instead of simply contemplating advantages in tempo or resources, the game augments these factors by introducing spatial considerations. Units can only move two spaces in any direction, making positioning a key consideration. Vulnerable glass cannons can be kept safe by placing them behind a defensive line, or beefier units can be thrown behind enemy lines to try and cut off retreat.

People’s favorite Hearthstone moments are usually when an unforeseen combo or bit of luck completely upends the field of play. But in Duelyst, I find myself drawn to the way incremental changes slowly pile-up until their cumulative outcome is all but inevitable. The game’s co-creator, Keith Lee, who was a project lead on Diablo III (2012), explained this design philosophy in an interview last year. “Everything we do is designed so that you know deterministically what you are going to get,” he said. With the exception of drawing new cards at the end of each turn, Duelyst tries to take chance out of the equation.

For all of the similarities to Hearthstone, this mode of pursuing victory more firmly cements the game’s relationship to chess. When asked how many moves ahead he played, the world chess champion José Raúl Capablanca is reported to have responded, “Only one, but it’s always the right one.” Where others might try to over-engineer their victories, Capablanca played logically and concisely. What Duelyst does is take that sentiment and marry it to a lush and imaginative presentation.

There’s spectacle going on, but not the kind that will win a game in two turns. Defeats are hard-fought and victories feel more narrow, not least of all because the progress of a match is tied to the movement of actual bodies on a board rather than words on a piece of paper. Despite being confined to the intangible photons emitted by a computer monitor, nothing else has come close to capturing the methodical thrill promised by Wizard’s Chess quite like Duelyst.

You can find out more about Duelyst and start playing it over on its website.

The post Duelyst brings collectible card games back down to earth appeared first on Kill Screen.

Beads of Orange Glass is a wonderful piece of generative art

Commissioned for the No Quarter exhibition at the NYU Game Center, Loren Schmidt’s Beads of Orange Glass is now available for download on itch.io. The game is not interested in holding players’ hands through a guided narrative; instead, players shape their experience themselves as they explore the game’s rich textural space.

A two-player game, one player navigates the pixelated landscape while the other adjusts the minimal landscape, triggering rain showers and falling stars, growing moss, and planting trees. Players can change themselves, too—into deer, birds, and trees. Without words, Beads of Orange Glass tells stories through a generated world with random sets of verbs and characters to choose from.

players shape their experience themselves as they explore the game’s rich textural space

As with other games by Schmidt, then, Beads of Orange Glass puts players in control of determining the rules—at least in some ways—but the game’s system determines part of the story, too. It’s a generative form of storytelling, albeit wordless. And one that puts screen glitches and missing pixels at the forefront.

Similar to Strawberry Cubes (2015), another of Schimdt’s projects, Beads of Orange Glass itself is almost about entirely about those glitches: exploring them and how they move and shift as the game, too, moves and shifts. Glitches change as the color blends in and out, and pour down as rain. And the creator agrees; “the glitchiness seems integral somehow,” Schmidt posted to Twitter. Those moments are where the story comes to life; it’s the imperfect moments of ambiguity that bring forward feelings of something alive.

Beads of Orange Glass is available on Windows for $5. Follow Loren Schmidt on Twitter for more information on upcoming games. Schmidt is currently working on idyll, a game about climate change.

The post Beads of Orange Glass is a wonderful piece of generative art appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers