Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 49

September 29, 2016

The 3D-printed clitoris opens the door to sexual revolution

Over the past three decades, 3D printing has expanded from modest origins—a stereolithographic prototype designed by Chuck Hull of 3D Systems Corp. in 1984—to being hailed, in 2012, as the vehicle of a third industrial revolution. In the past few years alone, we’ve 3D-printed Van Gogh’s ear, a hi-tech waterproof bikini, some synthetic rhino horns in an attempt to stop poaching, and began to make real inroads into the world of 3D-printed prosthetics. At this year’s Paralympic games in Rio, Denise Schindler became the first Paralympic cyclist to use a 3D-printed prosthesis. Oh, and you can also turn your child’s latest drawing to sculpture for a modest-ish fee.

A new anatomical model could change sex education as we know it

And now, 3D printing has yielded a new anatomical model that could change sex education as we know it: a full-size clitoris. Until now, the most accurate representations of the clitoris were three-dimensional MRI scans that date to 2009—before which, if you can believe it, the true nature of the clitoris was a complete mystery. But finally, in 2016, women will finally know what the entirety of their primary sexual organ looks like and, with any luck, young girls will soon have access to the model in sex ed classes. (French students will begin to make use of the model this month!)

The common perception of the clitoris, asserted by dictionaries and textbooks alike, is that it is a small, sensitive organ (called “pea-sized” or referred to as a “button”) located at the top of the vulva. This 3D model, a collaborative project from independent researcher Odile Fillod and photographer Marie Docher, decidedly proves otherwise. It refutes myths that have long repressed female sexuality and will hopefully lead to a demystification of that oh-so elusive thing: the female orgasm.

The model makes clear that, in addition to its visible head, or glans, the clitoris includes two shafts, or crura, about 10cm in length, which encircle the vagina. So, rather than a button, the clitoris in actuality appears to resemble a wishbone, or, aptly put by Minna Salami at The Guardian, a fleur-de-lys or (most thrillingly) a tulip emoji. Speaking for all of us (I would like to think), Salami writes, “[I]magine a world where it is common knowledge what a woman’s primary anatomically sexual organ looks like. Imagine how sexually empowered women who can visualise their clits will be.”

The post The 3D-printed clitoris opens the door to sexual revolution appeared first on Kill Screen.

Merger 3D combines the best and worst of 90s shareware

Nostalgia for the 1990s seems to have become the stock in trade for videogames over the past few years. I’m thinking of the tongue-in-cheek revisit to MS-DOS’s glory days of Vlambeer’s GUN GODZ (2012) and the brutal, tasteful modern reconfiguration of the 90s shooter in this year’s Devil Daggers.

But these are exceptions, as drawing from that well is typically an exercise in diminishing returns. A new shooter, Merger 3D, is testament to this, as it showcases the best and worst of the 90s shareware aesthetic. The title weighs in at a svelte 10 MB, and supposedly will run on every Windows OS released in the past 20 years (if you can somehow manage to get Steam running on Windows 98).

Quit whining about remappable keys

Aside from the option to play in modern widescreen 16:9 or CRT-legit 4:3, modern niceties, such as editable options of any kind or a map, are out the window. Quit whining about remappable keys and get to the important stuff, you pansy: get out there and kick some mutant ass.

In a plotline that reads like it was generated from a “90s action movie” grab bag of magnetic poetry, you’re a soldier out to destroy bio-terrorism as a result of human cellular modification. Along for the ride is your “special unit formed by mercenaries who opposed human extermination,” in case you were worried about our heroes being on the wrong side of the hot-button issues of the future.

Merger 3D manages to provide a stiff challenge with health and ammo in short supply and zero reliance on auto-aim, but ultimately falls into the trappings of so many bargain-bin titles of the 90s. FPS forebearers like Doom (1993), Wolfenstein (1992) and Marathon (1994) are still held in high regard by allowing the player to rely on strategy of movement around an arena, of which Merger 3D completely ignores. Enemies hone in on the player’s movement the second they’ve been spotted, making confrontations more a matter of hammering the fire button in every direction rather than the gloriously cheeseball ballet of death it ought to be.

Shareware titles were novel in the fact that you were able to take your new, expensive PC and find something to run on it—it didn’t much matter what it was. For every classic like Doom or Commander Keen (1990), there was a Bio-Menace (1993) or Jazz Jackrabbit (1994) to slog through. Merger 3D certainly isn’t the worst throwback title to hit Steam Greenlight, but it calls to mind the games that the 10-year-old version of me would probably own on a hand-labeled disk, rather than one I’d plunk down my hard-earned allowance money on.

You can purchase Merger 3D on Steam.

The post Merger 3D combines the best and worst of 90s shareware appeared first on Kill Screen.

Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor is a treasure among the trash

There is a sense, in videogames particularly, that the greatest science fiction is that with the budget to match its ideas. Most sci-fi games seem engaged in a kind of arms race, a process of trying to out-tech and out-spectacle each other with increasing elaborate retellings of the “save the galaxy” narrative. Yet, in many ways this is the realm of the blockbuster, not of science fiction as a genre. The most impactful sci-fi of the past was not that which hammered the most fancy widgets onto a five-act quest structure, but that which abstracted, twisted, and expanded the struggles of its time into a fantasy of technological growth and societal tension.

Think of Philip K. Dick’s 1960s existential struggles with mind-expanding substances, heightening the paranoia enforced by a McCarthyist regime. Or William Gibson’s vision of technological subcultures, which grew from the explosion of home computing in the 1980s and the acceleration of rampant financial inequality. Even the 1990s had Neal Stephenson, generating surreal self-aware fictions from the latent energy of the dot-com boom. Science fiction is that dark, twisted mirror we hold up to our world, a form which is as innately human as it is technological.

a precise portrait of what it means to be young and poor in contemporary society

Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor is a game in that tradition. From first impressions, it appears to be a loop of pleasing routine, packaged in the cute colors of a Star Wars pixel-art demake. It seems like a game interested in providing the player with a space in which to live and thrive, rather than a linear adventure to undertake. Yet Spaceport Janitor quickly upsets this idea. Putting you in the shoes of an androgynous blue-skinned street cleaner, the game abandons you to a world that doesn’t care about a thing you do, as long as you do your job. That job is a simple one: wander the streets of the spaceport and incinerate the trash you find.

Each day follows the same pattern of waking up, collecting your pay (always less than you thought), trawling the streets, haggling for food, getting lost, getting tired, and stumbling home to sleep. At every turn the game reminds you of your lowly position in its brightly-hued society; the insults hurled at you by the local law enforcers, the exorbitant food costs that eclipse your wages, the crowds you navigate as if you were invisible. While the likes of Animal Crossing, Stardew Valley, and Harvest Moon place their protagonist at their center—the shops, services, and systems of their worlds built to provide for every need—Spaceport Janitor does the opposite, constantly enforcing your hand-to-mouth lifestyle with each moment. It doesn’t do this through scripting or an overbearing narrative of dejection and depression, instead it simply sets up the systems and lets you build the narratives in between. The result is a precise portrait of what it means to be young and poor in contemporary society.

On top of this societal disconnection, the game adds a physical dimension—the need to switch gender. Every couple of days, static clouds the screen, text scrambles, and the world wavers as if it were a mirage. This worsens as long as your gender remains unchanged, a process which, though simple within the confines of the game, is often beyond the money you have left at the end of the day. If this wasn’t enough, the game also labors you with a curse—a skull which dogs your steps, occasionally and unexpectedly screaming in your ear. Though I have no experience of gender dysphoria, Spaceport Janitor clearly wants to put its players through a highly abstracted version of a very personal experience; the discomfort and distress that emerges from pronounced “difference.” The combined effect of the societal systems and this physical distress means that Spaceport Janitor forces you into a place of precarity and poverty, where survival, not success, is your daily focus.

To survive Spaceport Janitor you have to rely on what you can find thrown away on the spaceport streets, which it turns out is quite a lot. Spaceport Janitor does its best storytelling with these little pieces of trash and their descriptions. A “Hi-pleasure chip” can’t be used because the player doesn’t “have the necessary bioport,” and an “adventurers wanted” flyer (complete with tear-off strips) suggests that a fantastic escape might be just one phone call away. Some of these items have potential value at the city’s constantly shifting set of market stalls, others are totally useless. Either way, if you don’t incinerate them, you won’t get paid. This choice between holding onto something potentially useful or interesting versus incinerating it and getting on with your day gives each new discovery a moment of tension. The odds are stacked against you, of course, with the chance of finding an expensive item and then selling it to a shop that will take it being very low, and yet the rewards for such a moment are huge. And perhaps even more tempting is the carrot of adventure and dungeon crawling that the game constantly dangles under your undernourished nose.

Though Spaceport Janitor’s main quest (ridding yourself of that screaming skull) brings you to the border of the world of adventurers and explorers, the game still keeps you strictly on the outside. It plays on expectations of the genre with care, constantly feeding the hope that we might be taken in by the mages guild, or be rescued for a life of adventuring with a team of aliens in tow. This tendency for daydreaming is carefully supported by the game’s setting. This is no downbeat contemporary city or gritty sci-fi wasteland. In sharp contrast to its often punishing structure, the spaceport is the brightest of sci-fi worlds, buzzing with a seemingly endless stream of strange creatures, occult weapons, mysterious technology and ancient artifacts. It’s less Star Wars and more Adventure Time or Samurai Jack, appropriating and remixing with an infectious energy. This is a fantasy after all, and its layering of RPG tropes into its dulling systems of daily routine inject it with a clever twist. It feels like arriving at recognizable territory from a different angle, not quite a parody and not quite a tribute, but somewhere between, nestled in the fantasy and the reality of both our own world and the science-fiction worlds it has spawned.

Within this lively fantasy, Spaceport Janitor homes in on big, powerful themes: inequality, identity politics, division, and the precarity of the young. The game positions itself around these issues not because of some high-concept intention, but because it was built by people whose experiences were forged in the pressure cooker of trying to make a living as a young adult in the world today. It claims science fiction for itself, reinvigorating a genre owned by big studios and the power-brokers of our media, as a scrappy, emotional thing; a way of living in both our daily fantasies and our daily realities simultaneously. It is not doing this on its own, of course—you can feel the influence of artists like Porpentine and Nina Freeman, and all those who refuse to make science-fiction games that aren’t personal, weird, or political.

Yet there’s something about Spaceport Janitor that feels so attuned to our times that makes it stand out among these works: its focus on the concept of luck. Luck is Spaceport Janitor’s way of letting you skew things back in your favor. In its world there are nine goddesses, one for each of the nine days of the week. By praying to them, leaving them offerings and avoiding cursed objects you can increase your luck, making you more likely to find valuable trash and win useful items from the daily lottery. Yet, luck can be a tricky thing to manage. Leave a bad offering and you might mess up your chances, incinerate a sacred object and you will find yourself on the wrong side of the goddesses. And stepping on spirals? Sure to bring you bad luck. Spaceport Janitor bombards you with this kind of inane advice, and the esoteric nature of gathering and maintaining luck turns you into a superstitious player, the type who will rub themselves against a giant sword if it means a chance at finding a credit chip. Whether it works or not.

encouraging the player to find meaning in the play of circumstance

In contemporary society, luck is explicitly connected to one of the biggest features of current political and social debate—privilege. For many in the highest earning and most powerful positions of our societies, luck is the preserve of the failed and the poor. Rather than thinking of themselves as lucky, entrepreneurs, businessmen and politicians often describe themselves as “self-made”. They are, they propose, proof that the dream of social mobility exists, that anyone can make it big with hard work and dedication. Only last week, Oculus founder Palmer Luckey was connected to right-wing meme factory Nimble America by a (now deleted) statement on he made on Reddit saying: ‘America is the land of opportunity. I made the most of that opportunity. I am a member of the 0.001%. I started with nothing and worked my way to the top’. Luckey’s refusal to acknowledge luck in his success is symptomatic of a society where groups still refuse to accept the privilege (regarding gender, race, ability, or class) that allowed them access to positions of power and influence.

In its focus on luck as the sole refuge of your downtrodden character, Spaceport Janitor refuses to accept Luckey’s claim and the prevailing wisdom that hard work is the only thing standing between an individual and their success. Instead, it acutely depicts a reflection of our societies repeated failure to protect those that are most vulnerable, by blaming them for their own systemic oppression. The game’s focus on luck also feels connected to an idea of generosity that is powerful in today’s society. Earlier this year, The Atlantic discussed a series of studies pointing to the idea that those who acknowledge the presence of luck in their own success are more generous with the rewards. Spaceport Janitor’s worldview reinforces this, encouraging the player to find meaning in the play of circumstance. Because, in the end, our only hope for rescue in Spaceport Janitor’s segregated, restrictive society is to turn to the supernatural, the divine, ultimately, the fantastical.

So when chance swings your way on a Theday, and the city comes alive with the tootling of alien trumpets and throngs with every creature you might imagine, it’s possible to rise above the trash, to appreciate the world for what it might be. Even on rainy mornings, where lightning whites out the single window of your scrappy flat, lanterns glowing green by the ceiling, there is a certain melancholic satisfaction to be felt, an appreciation of the process of being alive. I’ve had Onday mornings that felt like the crispest, crystalline fragments of time you can imagine, ready to be shattered by ceaseless onset of my working day,

It’s these delicate moments that point towards the optimism at the heart of Spaceport Janitor. By bridging the gap between our daily struggles and the daydreams that surround them, it suggests that the one space we truly own is our imagination. There is a certain beauty hidden in that sentiment; that it is the fantastic, the surreal, the strange, that might liberate us.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor is a treasure among the trash appeared first on Kill Screen.

Pavilion’s sublime architecture wants to be solved

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Pavilion (Windows, Mac)

BY VISIONTRICK MEDIA

Ancient murals on the walls of Pavilion‘s labyrinth depict you as an all-seeing eye and a huge hand from the sky—you are both. Able to see the path through the maze and interact with certain objects, your task is to guide a man from one area to the next. You do this partly by appealing to his instincts: he’s attracted to the heat of open fire, scared of the dark, and follows the chimes of bells. Later, you manipulate the environment itself, pushing large cubes out of his path and driving him across a railroad. Where you are taking this man is unknown; the game is without words. But there’s a woman that you chase and a house that you return to, all of it suggesting that the maze is a manifestation of the man’s psyche. The dreamlike quality of the aged architecture, which freely mixes baroque panels and Ancient Greek statues, only deepens the mystery.

Perfect for: Gods, architects, puzzle junkies

Playtime: Three hours

Buy Pavilion on Steam or at the Humble store here.

The post Pavilion’s sublime architecture wants to be solved appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 28, 2016

Botolo is all about the fluid poetry of 1v1 competition

The Floor Is Jelly (2014) creator Ian Snyder is working on a new game, Botolo—a competitive multiplayer title inspired by games like Street Fighter and Smash Bros. With Botolo, Snyder considered three aspects of competitive play: physical skill, mental skill, and game knowledge. Physical skill, “whether or not your hands do the right thing at the right time,” Synder said, is one of the biggest barriers in competitive gaming; likely, the least interesting, too.

Botolo is a dance

“With Botolo, I wanted to reduce the amount of time players needed to spend building those skills first before they could play the mental game,” Snyder told me. To do this, Botolo‘s controls are relatively straight forward; “the whole game is controlled by just a thumbstick and two buttons,” he added. “My philosophy was that if you can imagine it, you should be able to do it.”

So, unlike a game like StarCraft II (2010), where you can have a brilliant plan but totally flub it with the wrong timings, Botolo‘s mental game is unhindered by complicated controls and easy-to-understand gameplay.

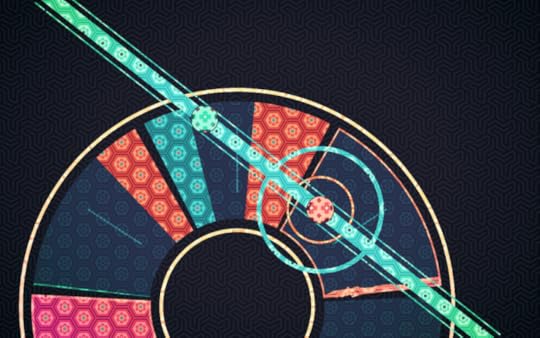

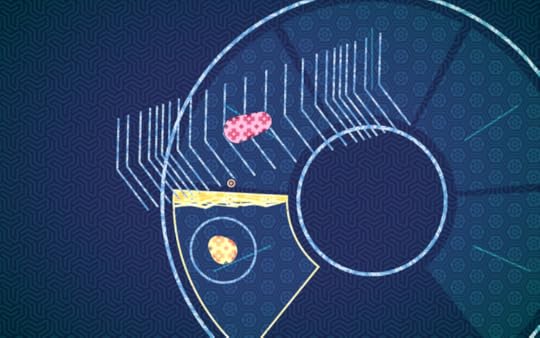

Players will have to capture colorful, patterned zones to win matches, all while chasing after and stealing an ability-changing ball from each other. By leaving the game’s core premise simple, Snyder is allowing the mental game—the meta—to add depth. Botolo is about the back-and-forth volley; it’s about developing a digital body language that evolves as the game continues. “Do I flinch when you feint? How do you move when you’re nervous? Am I more likely to block when I’m closer to winning or losing?” Snyder asked. “The body language we create together will be different from that of any other two people. How attentive each player is to that language will usually determine the winner.”

In that way, Botolo is a dance. Or learning a language. In a post on the Botolo blog, Snyder asked players to imagine skill in a game as a kind of language, where anytime players are playing, they’re actually holding a conversation. Players who are very good at the game have typically spent months learning the game’s language, “immersing [themselves] in its grammar of input, and the way [they] play is beautiful, fluid poetry.” Botolo’s simple controls make it easier for new players to learn that language. New players will be able to pick up the language easier than in other competitive games. “I want new players to spend less time learning to speak and more time speaking,” Snyder said.

Botolo will be released in 2016 for PC and Mac. More information is available on the Botolo website and Twitter.

The post Botolo is all about the fluid poetry of 1v1 competition appeared first on Kill Screen.

New game collection celebrates the kindness we bring to each other

In a year such as this one, it can be easy to be weighed down with how incredibly hard the world sucks. With so many horrific acts of violence, and a vomit-inducing election cycle, it can be tempting at times to shut down. But there is still good in the world, and Pictochic’s collection, Lovin’ Buttons, reminds us of that. In three little games, Lovin’ Buttons communicates the beauty and kindness of the connections we make with each other, on our phones, over the internet, and in person.

Sunday In The Park With Dogs

Yep, it’s exactly what it sounds like. You walk around with your dog, pet your dog, play ball with your dog, and pick up your dog’s poo. Along the way you can talk to the other people (and dogs!) in the park. Not everyone is happy, and not everyone is nice, but the game is sweet all the same.

Affectionet

Affectionet shows how using your phone to interact with people can make your whole life more fulfilling, keeping you engaged with people who care about you wherever you go, and pushing you forward to new and interesting situations.

Connect

Connect has you drag videos and pictures to different social media and messaging avenues showing how friendships develop online. Together, the games show how the variety of relationships you create and maintain make a life worthwhile.

One moment in Connect really encapsulates the whole of what I think Lovin’ Buttons reveals to us about the human experience. One of the friends you’ve made is crying. You can’t touch them to physically reassure them—their distance is signified by the impenetrable box they are huddled in. But you can stay around them on the outside, and drag memes and videos and content over to them. After a while they thank you, and say you helped. We can’t fix everything for each other, but we can make things a little nicer.

You can play Lovin’ Buttons for yourself here.

The post New game collection celebrates the kindness we bring to each other appeared first on Kill Screen.

Arrival is an alien-contact movie that’ll speak to you

I did not expect a new Denis Villeneuve movie to make me cry. The man behind Prisoners (2013), Enemy (2013), and Sicario (2015) is not known for his delicate touch, but his new sci-fi drama Arrival makes a staggering case for looking at Villeneuve with fresh eyes.

The logy, intellectually bankrupt posturing of Prisoners and Sicario has been jettisoned, leaving only the good bits: razor-sharp cinematography, perfectly-pitched scores, and strong performances. Here, those are courtesy of Bradford Young (Selma), Jóhann Jóhannsson (also Sicario, Prisoners), and Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner, and Forest Whitaker. Since his US debut with Prisoners, Villenueve has yet to direct one of his own scripts—his past films struggled to transcend dull writing despite their lavish aesthetics. Sicario, specifically, sees belabored visuals trapped in a death spiral with a truly stupid script.

It’s easy to imagine extraterrestrial contact going down this way

Reading the credits for Arrival, you may think you’re in for a similarly hollow movie. Writer Eric Heisserer has a depressing history—The Thing (2011) remake, Final Destination 5 (2011)—but his work here is solid. And Villenueve’s treatment of the script, based on a short story by Ted Chiang, is smartly visual. The film finds vivid, disorienting ways to tell a story built on recursion and unstable chronology without bending over backwards to Blow Your Mind.

Arrival is essentially a first-contact-with-aliens (they are pointedly not invading) movie funneled through the perspective of Amy Adams’s linguist. We’re with her through the entire thing, from the turmoil of the first days to the aftermath, and we’re also privy to her backstory, involving a daughter with cancer and a ruined marriage.

It’s easy to imagine extraterrestrial contact going down this way; you sit around at home waiting to be blown to bits or vaporized, watching snippets of news in between naps, caught in a species-wide limbo.

Adams’s character is drafted to translate the aliens’ language, a splattering of sounds from guttural moans to dolphin-like clicking. It quickly becomes apparent that the creatures—which, do not worry, friends, are eventually revealed in their full Zdzisław Beksiński glory—communicate in unimaginable ways. Their language collapses time and space into a sort of palindromic, simultaneous rush, because that’s how they experience time, and as she learns their language, Adams begins to … well, you should probably just watch Arrival when it comes out.

It’s the rare movie that feels like it could win Best Picture not because it’s an easily digestible pile of mush but because it’s the ideal winner of the golden nude man: impeccably made, gives you the feels, and all-around good.

Arrival was screened at Fantastic Fest 2016. It’s to be released on November 11.

The post Arrival is an alien-contact movie that’ll speak to you appeared first on Kill Screen.

Musikinésia, a game that teaches you music theory

Musikinésia is a game about mastering the telekinetic powers of a dusty piano by learning how to play a real one. Not long ago, Rock Band 3 (2010) had a plastic keyboard that let players get the hang of rhythms on the piano, and Synthesia (2013) got a little closer to actually being a pack of lessons by using the whole range of a MIDI keyboard as a controller. None of them, though, teach players about music theory as Musikinésia attempts to.

“I think that, first of all, [these games] pique the person’s interest for music,” said Rogério Bordini, game and sound designer of Musikinésia. “It’s so good to play Guitar Hero, Rock Band and feel like a drummer, a guitarist. People who never got in touch with music practice have, for the first time, a kind of experience and may be motivated to study further.” Bordini’s assertion is that, even though those previous music games don’t actually teach music theory, they give players a useful notion of rhythm.

Bordini went back to Brazil after a year studying in London, and as soon as he arrived a professor came up with the idea of creating an app that would help beginners to understand the piano keys and play them correctly. The Laboratory of Learning Objects (LOA, in Portuguese), where Bordini studies, took the project and started working on a game instead. “We brainstormed and came up with this game, which would be a kind of Guitar Hero for keyboards and learning sheet music.”

The basics of the game are similar to the 00s music games: play the right notes on the right beat and score as many points as you can until the song ends. However, instead of a dark grid filled with colorful notes, Musikinésia features a white pixel-art sheet music, with a black G-clef on the left with whole notes rolling on the screen until they reach it. The sheet music is on top of an illustration of a piano, where it’s shown which keys the player is pressing and if they’re correct—it’s nearly impossible to look at it while playing without missing some beats.

The point is that these whole notes and their position on the sheet music show exactly what note is being played. The game also indicates that the line at the bottom is E, the second one up is G, and so on. “We tried to make it an accurate experience, one as close as possible of playing a real instrument,” Bordini said. “If you’re playing in an orchestra, you’ll be paying attention to the sheet music, and your fingers must be properly placed on the instrument, whether it’s a keyboard, a flute, or a violin.”

some levels include tempo variations, accidentals—sharps and flats

One of the biggest concerns that the team working on Musikinésia has is balancing this educational core with something more friendly. It’s why the game walks the line between fantasy and reality. The choice to use pixel art was also informed by this concern. But the most significant effort to draw players into what is essentially an educational game is through the story of Tom, a boy who was cleaning his house and found a dusty piano. He’d never touched a piano before, but after playing some notes he found that some objects started floating around him, as in a telekinetic phenomenon.

In order to control the power of the piano, Tom starts to study and learn how to use telekinesis through music. “There’s a level with a duck stuck on top of a tree, and Tom has to help it to get down,” Bordini said. “That’s a lame example, but after a while he seals deals with the Italian mafia and fights pirates.” The protagonist, as the player, is a layperson on the piano, which may help them to identify with Tom during the campaign.

Musikinésia is made for music literacy. Even though the team at LOA believe its design is also a good fit for adults who know nothing about music theory, the game is aimed at children and teenagers at schools. Bordini’s experience with music education in Brazil and England has shown him that different countries have different approaches to the subject. In his words, music teachers in Brazil are more like general practitioners of the art. “In England, I felt this in a different way. They value it much more. There are actual music teachers in schools,” Bordini said. This is something that Bordini and his team are bearing in mind with the Portuguese and English versions of the game.

Music theory is quite extensive, but Musikinésia will help students with the basics as well as teach more complex topics in its latter levels. “We even wanted to approach harmonic fields, which is a very advanced subject in this area, but we had some issues due to limitations of the game’s interface,” explained Bordini. However, some levels include tempo variations, accidentals—sharps and flats—and the basics of chord formation, triads, and tetrads.

The team at LOA, despite being researchers, seem to be thoroughly analyzing the trends both in videogames and education to make their game accessible and understandable to everyone. “Sometimes we stick too much to the academia, to the university, we shut ourselves in there,” Bordini said. “But the more we bring this to the public, events, and schools, the more people will notice and benefit from it.”

A full version of Musikinésia is available at LOA’s website in Portuguese. If you want to play it in English, you can download an alpha version here. The full English version release date is the first quarter of 2017.

The post Musikinésia, a game that teaches you music theory appeared first on Kill Screen.

Hitman’s accent problem finally finds a solution (sorta)

Hitman, in most ways, has been going from strength to strength. The episodic murder simulator has seemingly found its form, with the space between each episode giving players plenty of time to experiment with its techniques and locations, finding increasingly outrageous kills and bizarre events. We’ve had “accidents” caused by launching a fire extinguisher at a Parisian balcony, setting up a totally improbable double kill with a trail of gunpowder in Sapienza, and in Bangkok the grim spectacle of smothering a man in his own birthday cake in front of his surprise party. I’ll understand if you don’t click that last one; IO’s sense of humor is as dark as it gets.

Despite this pleasing descent into the dark and bizarre, the Hitman episodes have also been suffering from a strange and pernicious problem. I didn’t notice it in Paris. I guess there were hints here and there, but seeing as it was a party full of international guests I just assumed they were all from out of town. In Sapienza I started to realize something wasn’t quite right. Sure, this was a tourist town, but was there really not a single Italian in the whole joint? It seemed a little strange. But it was in Marrakech where things got out of hand.

everything else about Colorado seems like a step back

“Salam,” said a street hawker as I passed him by, “would you like to buy a lovely lamp?” I paused for a moment as I passed. Why was this soft-voiced American selling lamps in North Africa? Thinking on that for a moment, I bumped into someone on the street. “Watch where you are going!” came the SoCal valley-accented response. I walked on, slightly unnerved, and that was when a woman, who spoke with the clarity and care of an L.A. news anchor, tried to sell me Escargot. Hitman has an accent problem. Despite its carefully realized exotic locations, rich in detail and atmosphere, lit with the care of a well-studied eye, every side character in them speaks like they came from a very specific West Coast state.

In fact, it often feels like there are only two men and two women voicing every pedestrian, party guest, street seller, police officer, guard, tourist, waiter, crew member, model, and maintenance man. The results can get pretty bizarre. Just listen to this conversation on Western materialism. Yeah. But turns out IO came with a plan to fix this: set the next episode in America.

Yesterday saw the release of the fifth Hitman episode, which brings Agent 47 to Colorado, a place where IO no longer have to worry about their voice acting. Yes, we might be in the wrong state, but versus their typical continental displacement, this is progress. Sadly everything else about Colorado seems like a step back. Grubby military base filled with waist-high walls. Check. Everyone is a guard. Check. Exotic location filled with interesting side characters. Well, no.

There are still plenty of strange kills to uncover beneath the gray of a dull Colorado dawn, but it’s not quite the same as the golden light of Bangkok, the beauty of Paris in the dusk, or that time in Marrakech when a strangely Californian member of the army told me to “tell Michael at the print shop to stop texting his girlfriend.”

I guess, to misquote Harrison Ford, IO can write that shit, but they sure as hell can’t find the right person to say it.

The post Hitman’s accent problem finally finds a solution (sorta) appeared first on Kill Screen.

Oh look, Slither.io had a baby with your biology textbook

Smash-hit mitochondria simulator Agar.io (2015) and its recent knockoff Slither.io took certain corners of the internet by storm a while back. If you’re confused to why this is, here’s a hint: they’re super addictive. They’re easy to grasp, have a manageable skill curve, and ring that bell in your brain that says “One more try!” It’s a simple but foolproof formula—the same reason you kept coming back to Facebook games in 2011, and the same reason you haven’t deleted Stack from your phone even though you swear you’ll never touch that thing again. You can’t stop swiping.

It sure resembles old entomology illustrations

But here’s the thing: Agar.io was about cannibalism in a cell culture. Slither.io was about greedy worms that can’t stop eating. The main idea carried by these games is that Mother Nature is hungry. So why fight it? We’re well overdue an a .io game that makes us forget we have a class to go to and has something more to teach us about its starving protagonists! Enter Insatia.

Insatia, a “carnivorous worm simulator,” is exactly what it sounds like. Give the Slither.io guy a millipede carapace, some sick pincers, and the ability to lunge at and sever the torsos of other worms, and you’ve got the gist of this game. It’s pretty to look at. It’s kinda violent. It sure resembles old entomology illustrations a whole hell of a lot. And, crucially—as with the other worm simulators that it will unwittingly usurp—it’s not complicated. All of the controls are on the arrow keys.

Just to shake things up, you may occasionally take the place of some of the prey grubs—equivalent to the glowing dots of energy you eat in Slither.io—and the creator’s website hints that there may even be a plot somewhere inside the game about how scary centipedes are. But the important thing is that now you can spend your working hours playing that snake game with more controls and full gore. Really, they’ve done us a service.

Bite into that alpha build over on Insatia’s website .

The post Oh look, Slither.io had a baby with your biology textbook appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers