Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 50

September 28, 2016

Five games to fall in love with in the Fantastic Arcade bundle

Five games from Fantastic Fest’s Fantastic Arcade are available as part of a fantastic bundle on itch.io: Nium, Alphabet, Inspector Woof, F2oggy, and Lassos. All proceeds from the Fantastic Arcade bundle will go to the next Fantastic Arcade, in efforts to bring more independent game makers to the show floor.

If you’re in Austin, Texas, you can play these games—and others, like Everything, Islands, and Sacramento—at Fantastic Fest’s Fantastic Arcade, which opened Monday. It’s free and open to the public, too, but only running until Thursday, September 29. The games there are playable on beautiful custom arcade cabinets.

Here’s a rundown of the games:

Nium

Announced just last week, Nium is designed by Downwell (2015) creator Moppin, and in collaboration with Japanese artist Nemk. The pixelated post-apocalyptic action game puts players in a abandoned exclusive zone that houses a variety of mutilated wildlife.

Alphabet

Katamari Damacy‘s (2004) Keita Takahaski and Canabalt’s (2009) Adam Saltsman are behind Alphabet—the cute alphabet obstacle platformer that makes use of every letter key on players’ keyboards. Plus, the game’s song is really cute. Alphabet was originally part of the LA Game Space’s Experimental Game Pack.

Inspector Woof

A procedural generated mystery adventure game set in a high school full of vegetables, Inspector Woof in The Veggie Highschool is game where players have to seek out students’ terrible, terrible secrets. And there’s lot of them. And you’re a dog. Thanks, Klondike.

F2oggy

Independent Games Festival winner Nathalie Lawhead has a new frog combat simulator called F2oggy (Only One Survives!). It looks chaotic, with tons of frog annihilation action. Frogs in F2oggy must battle to the death on a small island in a sea of lava.

Lassos

Lassos, a game for the Texan in all of us. “Throw lassos, get money,” they say. The lo-fi game by Sokpop Collective is similar in art style to their other games, like Tom van den Boogaart’s Digital Bird Playground.

All five games are available as part of the Fantastic Arcade Bundle for $15 on itch.io.

The post Five games to fall in love with in the Fantastic Arcade bundle appeared first on Kill Screen.

The cycles of violence in BioShock: The Collection

Between 2007 and 2014, Irrational Studios and 2K Games told a story. This single story had five acts: BioShock (2007), BioShock 2 (early 2010), Minerva’s Den (late 2010), BioShock Infinite (2013), and Burial at Sea (2013-2014). Since episodic presentation encourages isolated judgment, it wasn’t always easy to see the unity of these fragments as they were marketed and released. But the legacy of the BioShock series is marked by rigid and often irrational schisms: between expectations and reality, themes and mechanics, rabid fans and equally rabid detractors.

Now that 2K has kindly assembled all these narrative segments in BioShock: The Collection, we can bracket the question of the individual games’ authorship and look at the object itself. We see that the object is a circle. Episode two of Burial at Sea, the beautifully nihilistic conclusion to the series, ends right where BioShock begins. In the twisted chronology of the game, this means that the series both begins and ends with formidably gifted women (Eleanor Lamb and Elizabeth Comstock) making history-altering decisions. We see that the BioShock galaxy is, in fact, filled with brilliant, talented, complex women—Elizabeth, Eleanor, Brigid Tenenbaum, Sofia Lamb, Grace Holloway, Rosalind Lutece—and a host of snarling, unraveling men at the desperate extremes of their power. We see the precise point where ambition becomes hubris.

this question turns out to be extremely hard to answer

We also see a very large amount of entrails. It must be said that the entrails look exceptional in these remastered editions. The color schemes and textures in the first game seem to have been retouched from the bottom up, so that you notice whole new layers of intestine and artery when you inspect the crucified experiments of deranged plastic surgeon Dr. Steinman. The infiltration of the seabed into Rapture in BioShock 2 is newly rendered in bright purple and orange, which provides a pleasant distraction between episodes of drilling into people’s faces. If these are the pleasures you seek, then these new editions will serve you very nicely. For those who object to BioShock’s violence in principle, on the other hand, the remasters simply exacerbate the problem.

I suspect that most of us are caught somewhere in between. We care about the principles as well as the practice, and feel the dissonance between them. In a post-Gone Home (2013) world, we wonder if these portraits of Rapture and Columbia might look better without so much red. But the BioShock games are not violent by accident. One of the reasons they received such sustained attention in the first place was that few shooters have so incisively explored the motivations and consequences of violence—and none have done so with BioShock’s self-awareness. Without discarding the reasons for the shift in critical opinion against the games, it is worth considering whether having Irrational’s dystopias all in one piece might still help us understand the growing violence and discord of what is rapidly becoming our own.

///

Suppose you had never read a word about BioShock. You don’t know who Ayn Rand is; you don’t know what art deco means. Ken Levine is a non-entity. It is, I submit, unlikely that you would come away from playing the game thinking about the ethical ramifications of rational individualism. You would probably not harbor strong feelings about ludonarrative dissonance.

If someone asked you what the game was about, you might say that it was about killing deformed people in an underwater city. Here the conversation can go two ways. They might ask you how it was, and you say, it was okay. It was pretty fun shooting all those mutants. Alternately, suppose your discerning interlocutor hears your description of the situation, furrows their adorable brow, and asks, “Why?”

BioShock remains a great game because this question turns out to be extremely hard to answer. If someone asks why you jump on the goomba, you can answer that you’re trying to save the princess. You’re shooting those Nazis in Call of Duty (2003) because Nazis are bad and you have orders. In a way, these are meta-explanations, artifices of the narrative that substitute for the fact that you’re shooting Nazis because it gives you pleasure (and you’re not really shooting anyone). But within the reality of the game, where you don’t exist, those explanations are what must carry validity.

For the first third of BioShock, you’re killing people because a voice on the other side of a shortwave radio begs you to save its family. Seems reasonable. After that, this unseen voice, Atlas, convinces you that Andrew Ryan, the brilliant but ruthless founder of this failing utopia, was the one who murdered his family. But when you kill Ryan, you learn that you weren’t choosing to do those things at all, because Atlas had you brainwashed from the beginning. If he was able to make you do anything, however, why did he bother with the story about his family? This emotional appeal circumvents the exigencies of your avatar and speaks to you, the player, directly—which is to say, it’s a dirty trick. Those seven or eight hours where you lack free will just wouldn’t be as fun if you know you lacked it, even though this lack of agency would acquit you of the slaughter.

But let’s stay within the game. Before you kill Andrew Ryan, you learn that he is your biological father. You, Jack Ryan, were purchased as a fetus by bad guys and engineered to become a living, killing automaton triggered by a certain phrase. Naturally, dad is disappointed. Yet Atlas’s lies about his family implied a nascent self-awareness within young Jack, who is eager but unable to find ethical justification for his instinctive slaughter. This tension reaches its peak in the fatal encounter with Dad Ryan, where the noble patriarch triumphs over the bovine gaze of your determinism by giving you the kill order himself. In making explicit the distance between action and awareness, this sacrificial moment represents the genesis of self-consciousness in Jack Ryan, and through him, in the game.

However, the game doesn’t end there. After a sojourn with Dr. Brigid Tenenbaum, who is the closest thing Rapture has to a guardian angel, you proceed to free yourself from the mind control. For this last third of the game, the new and autonomous you could hypothetically do anything it wanted—catch another plane, see an opera, hit the fairway. Instead, you do exactly what you have been genetically, behaviorally, and environmentally conditioned to do: you kill more people.

Here we come to the dark heart of the BioShock series, which was never about anything other than cycles of violence. In a hundred different pre-recorded voices these games speak the same sentence: blood begets blood. The flimsy choices occasionally served up to the player—most famously, the decision to save or harvest Rapture’s victimized Little Sisters—are ruses in the same way Atlas’s family was a ruse. They flatter self-consciousness to disguise the tortuous circle of determinism: consciousness is a product of its biology, biology is a vehicle for consciousness, and both are shaped by their environment. If you are bred for death and your body is infused with weapons, you will become one yourself, regardless of your feelings on the matter. It is folly to think that we can break out of the circle by choosing to press square or triangle, because the choice will already have been made by our past experiences.

The idea that cruelty and oppression perpetuate themselves is clearest in BioShock 2, which builds on the domestic themes of the first game. BioShock introduced the Little Sisters—young girls who are nightmarishly transformed into walking steroids—and the beefy Big Daddies that protect them. BioShock 2 makes you a Daddy and gives you the opportunity to lovingly raise your favorite Little Sis, Eleanor Lamb. If you harvest the other Sisters and kill a series of semi-innocent bystanders, Eleanor becomes a bloodthirsty super-person poised to take over the world. If you spare the Sisters and bystanders, she does pretty much the same thing, but smiles more. But if you choose to protect the Little Sisters, you also have to stand watch and mow down addicts while narco-Sis feasts on the local corpses. In the end, the choice to save or devour these children is simply a choice between two kinds of slaughter.

///

BioShock 2 has enjoyed something of a resurgence in popularity recently, and it is not hard to see why. It gathers all the series’ themes and presents them on a smaller scale, and with a grace that is lacking from the other games. It is a quieter, more contemplative experience, a shooter that is constantly giving you opportunities to do things besides shooting, like the lonely strolls along the seafloor that substitute for the original’s invisible Bathysphere rides. I’m happy to agree that it is the best BioShock game, if these are the standards we’re interested in. But it is also the safest BioShock. It works entirely within the template of the original, inverting the ideology and the gender of its antagonist but maintaining the same power structure, the same artificial either/ors, and the same gratuitous bloodshed. I love it, but set alongside the feverish inventiveness and jarring contortions of its younger and older sisters, it dims.

BioShock 2 was followed by BioShock Infinite, which has more in common with its predecessor than is generally acknowledged. Eleanor Lamb is reimagined as Elizabeth Comstock (née Anna DeWitt), who shares her Big Sister’s supernatural gifts and patricidal tendencies but has the advantage of being an actual human being. Early in the game your protagonist, Booker DeWitt, frees Elizabeth from an angel-shaped tower in which her father imprisoned her. Much of the joy of playing Infinite after this point is simply watching her experience the game’s marvelous floating city of Columbia. Unlike all of the ghosts chattering in your ear throughout the first two games, Elizabeth is right there beside you. She dances; she sings; she dreams of Paris. And after just a few hours in Booker’s presence, she learns to kill.

While both BioShock 2 and BioShock Infinite analyze the perpetuation of violence at the domestic level, Infinite takes the bolder step of analyzing historical cycles of oppression. Comstock’s Columbia is portrayed as a cartoonishly bigoted, authoritarian state that gathers together all the worst currents of early 20th century American ideology—phrenology, social darwinism, revivalism, and old fashioned racism—and submerges them under an idyllic, bourgeois surface. The main plot of the game follows Booker and Elizabeth as they give aid to the Vox Populi, a multicultural underground movement fighting for the poor and exploited. Your goal is basically to find them a big pile of guns, and when you do, they start their revolution—which turns out to be its own reign of terror.

we want to live and think without gods, kings, or other patriarchs

This particular plot point has been a matter of considerable controversy since the game was released, but the violent uprising of the Vox is exactly what we would expect from the historical logic of these games. Andrew Ryan was a Jewish victim of Bolshevik intolerance who transforms his own suffering into an ideologically repressive state. Eleanor Lamb, exploited by her mother Sofia, learns a lot of bad lessons from her big daddy and becomes the most deadly being in Rapture. Elizabeth is eventually recaptured and tortured by Comstock, ending up as the apocalyptic messiah he wanted her to be. And the Vox Populi, demonized and oppressed, take on something of a demonic aspect themselves.

It is, of course, no defense of the idea that oppression perpetuates itself to say that it is persistent across the series. But it is not a thesis we can just laugh away either. It may be worth considering that BioShock Infinite is a precise illustration of Karl Marx’s proclamation in The Communist Manifesto (1848) that “not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons—the modern working class—the proletarians.” Marx wasn’t using metaphors here: he knew that the revolt of the proletariat would be a violent one, and he thought this was as historically inevitable as the rest of the process. It wasn’t politics or ethics; it was simple causality. Since BioShock Infinite never lets us see what kind of government the Vox Populi sets up for Columbia, we really don’t know what their politics are. But it seems disingenuous to be shocked that their rebellion against Comstock’s insidious regime would be a violent one, or appalled that they might take some righteous pleasure in that violence. After all, don’t we?

I don’t mean to suggest that there aren’t problems with the way BioShock Infinite handles all of these issues. These problems have been exhaustively and enthusiastically documented by critics online, and given the generally adulatory disposition of most game criticism, one can only take this kind of analysis as a healthy sign. In particular, it must be noted that Infinite’s treatment of racial issues is clumsy at best and abhorrent at worst. Of all the (false) decisions that the creators could have offered you, it is ludicrous that they decided to give you a baseball and a bound biracial couple for a target. And the caricatures of Chinese people and Native Americans in the Hall of Heroes are vile things that make an already pointless chapter of the game more distasteful. These moments deserve to be excoriated.

At the same time, Infinite’s core invocation of historical materialism adds a new dimension to the determinism that all of the games explored at some level, and poses a fresh challenge for anyone who considers themselves a political descendent of Marx. Contemporary leftists have a tendency towards the the absolutization of ahistorical values—equality, inclusion, identity—but we have yet to reconcile this tendency with the historical and cultural perspectivism that seems appropriate to a post-global society. We believe in freedom, but only to the extent that it lets us affirm what we already are. Not unlike Ayn Rand, we want to live and think without gods, kings, or other patriarchs; unlike Rand, we haven’t been all that concerned with the vacuum of ethical legitimacy this abdication leaves behind. Columbia and Rapture are nothing more than illustrations of what happens when the vacuum isn’t filled.

///

There is a second cycle running through BioShock Infinite. We have followed the circle of determinist damnation in its many guises, but there is also a circle of redemption. This circle moves from death to life and back again. It was anticipated by the immortal Jack Ryan in BioShock, whose perpetual in-game resurrection (via the conveniently located Vita-Chambers) so nicely dovetailed with videogame conventions that it was easy to miss how audacious it actually was. Infinite’s Booker DeWitt is also a subject of the eternal return; we learn late in the game that the whole narrative of BioShock Infinite has already happened hundreds of times, and every time, Booker fails to save Elizabeth. The game, and the universe of the game, only comes to an end when Booker recognizes that the problem is himself: he is Comstock, and Elizabeth is his daughter. So Booker’s final and only truly heroic act is to surrender himself to being drowned in the baptismal waters.

the march into an inglorious death can be the highest form of redemption

But the BioShock story doesn’t end with Infinite. Elizabeth DeWitt’s drowning of her father should have put a permanent end to the story, but the game brings him back for one final tour of Rapture in Burial At Sea. It makes no sense, but it’s worth it to see Booker interact with the new, more assertive incarnation of Elizabeth. She has very little patience this time around for the emotional distress caused by your role as ex-pater familias, and isn’t afraid to sneer a little when you drink 10 bottles of whiskey on the pretense of “refilling your health bar.” Ultimately, neo-Elizabeth uses one of the Little Sisters to bait you into being killed by a Big Daddy, so that justice can be served yet again. Despite the new look for you and your companion, things start to feel a little familiar by the end of Burial’s first episode.

The beginning of episode two resets everything. You now inhabit Elizabeth, who seems to have finally made her way to Paris. But this is a Disney Paris, where artists from different centuries line up to paint the Eiffel Tower and bluebirds perch on your finger to tweet “La vie en rose.” This bizarre opening chapter doubles down on the deliberate cartoonishness of Infinite’s Columbia in order to emphasize the impossibility of genuine escape from one’s past; it is the too-bright light before the familiar darkness. And things do get dark once you go back to Rapture: episode two culminates with our old friend Atlas performing most of a transorbital lobotomy on Elizabeth, which you experience in visceral first person. Shortly after, with full awareness of her fate, she walks into a room and lets him smash her skull with a wrench. So ends the tale of Columbia’s first daughter; not with a bang, but with a whimper.

Elizabeth’s death isn’t any less meaningful than Andrew Ryan’s own self-sacrifice, but it does have a different meaning. Ryan wanted to uphold the value of choice: “A man chooses, a slave obeys.” Elizabeth is neither a man nor a slave; she has seen the consequences of powerful men deciding how the world should be, and recognizes that their murderous instincts have been passed down to her. She does what she came to do: she saves Sally, the Little Sister she hurt to bait Comstock—and for all its futility, it feels like a real decision at last. Then she follows the example set by her father, and submits to the waters of redemption. When everything you do and everything you are is corrupt, the game suggests at last, the march into an inglorious death can be the highest form of redemption.

Or maybe BioShock hasn’t given us the final word. As she submits to her burial at sea, Elizabeth gives Atlas the key phrase he needs to bring down Jack Ryan’s plane, initiating the sequence of events in Rapture that will eventually—after all the seismic shifts of power in the first two games—lead to the ascent of Eleanor Lamb into the world above. The rest is hazy; we are told in BioShock 2’s final moments only that the world is going to change. If the series does continue, perhaps we will get to stay on the surface and see its transformation. We could follow Eleanor Lamb as she continues to learn from her fellow humans, and see how she deals with the fact that she is something a little more than human. She will decide whether she wants to harvest us, or save us; she will be the Big Sister that Orwell never saw coming, or the angel from below that takes us to a higher plane. She has only to transcend a history of violence—to throw off the weight of a family’s legacy, and a city’s, and an entire world’s. Then, at last, the circle might be broken.

The post The cycles of violence in BioShock: The Collection appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 27, 2016

Sundered’s eldritch horrors are terrifying and spectacular

Thunder Lotus’s debut title was one of giants and gods, bringing North mythology to hand-drawn life in Jotun (2015). It was a title about scale, your shieldmaiden Thora often small against the sprawling landscapes, colossal architecture, and raging behemoths. Each enemy felled felt like a titanic victory, a true David-versus-Goliath moment born from your own skills and tenacity.

Now, the studio’s sophomore effort, Sundered, promises to transplants those incredible odds from the land of Yggdrasil and Jomugandr to a world of gothic horror and otherworldly evil. It’s due out in 2017 and, to mark the announcement, we have been bestowed a trailer.

Caverns of flesh and gristle. Gnarled architecture and looming statues. The world of Sundered is deep within a subterranean hell, where eldritch monstrosities lurk and a warrior can easily be forever lost in shifting tunnels. While the detailed and smoothly-animated hand-drawn aesthetic remains, Sundered has eschewed its predecessor’s isometric camera and different realms in favor of side-scrolling traversal through a procedurally-generated interconnected map.

Caverns of flesh and gristle

Much like Jotun, your greatest foes will tower over your wandering warrior, beasts armed with metal limbs that unleash projectiles and beams of hellfire. But a more insidious threat roams in Sundered‘s procedural tunnels, tentacled creatures that swarm upon the player in unpredictable patterns that encourage you to explore cautiously and react on the fly.

Sundered is slated to release on Windows, Mac, Linux, and PS4 in 2017. For more details on the game and developer, you can visit their site here.

The post Sundered’s eldritch horrors are terrifying and spectacular appeared first on Kill Screen.

An unfinished demo provides a surreal meditation on grief

Outside, the waves crash against the shore rhythmically. Inside, a broken robot suit lies sprawled on a bed, one arm yanked off and left dramatically on the floor. It’s accompanied by a keyboard that, upon further inspection, is literally made of gold. You can pick up the broken arm, or attempt to play the stubbornly immovable keyboard, but your cautious avatar doesn’t want to go near the robot. That’s understandable, as she just came to this beach, this cabin, to mourn.

This is, more or less, the unfinished demo recently released by Arielle Grimes called Simulus, subtitled Cabin in the Cache. Weirdly enough, for a game that involves dead robots in mysterious cabins, mourning is actually how it starts.

the pressing weight of grief ever-present

The player is going through a personal tragedy. The feelings are written out on pink post-its, vague and incorporeal as devastation always is, and peeled away piece by piece as the player settles into her skin. You go to the ocean to get away. It’s a relic of childhood memories, providing some semblance of solace after the turmoil and hurt of the past. You turn to your right and spot a cabin.

Herein lies the robot. The cabin—or the part we see in the demo, at least—is a barred-off tunnel, a door that looks closer to a bank vault than a vacation home, and an open hallway leading to the aforementioned room and its strange, surreal contents. You take this in stride. In the grand scheme of things, with the pressing weight of grief ever-present, the unreal is just another thing to process.

That’s where Simulus really shines. The strange, skippy way it stutters through the description of a tragedy; the alien haze that hangs over the whole world when you are mourning. The space between the two makes more sense than it should.

Play the Simulus demo (Cabin in the Cache) on itch.io.

The post An unfinished demo provides a surreal meditation on grief appeared first on Kill Screen.

Help sad fruit people overcome loneliness in a new game

Have you ever bought a piece of food and for whatever reason left it out or forgot about it? After some time it begins to rot, dry out, or expire. Most of us would simply throw it away, but Agata Nawrot did something different: instead of tossing the spoiled food away, she was inspired to create Karambola—a strange and beautiful game about lonely fruit people.

“I like strange concepts,” Nawrot told me. A village of emotional fruit people who are kidnapped by evil, magical birds certainly qualifies as a bit strange. The idea came from a single bulb of dry fennel that she purchased in an effort to eat healthier, but never used it. It got dry and started to look “sad” according to Nawrot.

“I imagined it must feel really useless,” she continued. “ I was quite depressed at the time and identified with it. So I started drawing these sad veggies and fruits.” Eventually these drawings began to form a story. Initially, Nawrot thought of turning it into a book, but opted to create a videogame instead.

Nawrot has created Karambola almost completely by herself—for the music and sound she enlisted the help of a few friends. It hasn’t been an easy process given that this is the first game she has ever worked on. Nawrot had to learn how to program, animate, and work with music and sound effects, bringing it all together to create a cohesive and interactive world. But the struggle had led to many positive effects. “Making Karambola was an adventure for me that helped me deal with the same stuff that our fruit people are going through,” Nawrot said.

“The fruit people don’t realize they are really in a beautiful world”

Karambola itself is inspired by the point-and-click classics Nawrot loved when she was younger. Games like Grim Fandango (1998) and The Curse of Monkey Island (1997). And like those games, Karambola asks you to solve puzzles, but not ones that are as obtuse or difficult as those found in older adventure games. It’s a pleasant mix of straightforward puzzles, like having to correctly arrange pieces in an image, as well as less obvious puzzles, like having to play a musical instrument guided by small markings subtly placed on a tree.

When you’re not wrapped up in the puzzles, Karambola‘s art should hold your attention—colorful, naturalistic environments inhabited by black and white characters. The contrast is a big part of the game. “The fruit people don’t realize they are really in a beautiful world, because they’re stuck in their thoughts,” explained Nawrot. Solving each puzzle helps free the fruit people and brings them one step closer to reuniting with their friends.

Nawrot hopes that Karambola will move beyond mere entertainment and “help all the lonely souls feel a little less alone.” It seems that making it has helped her get through a period of loneliness himself. “My dream is that the game will be heart lifting for those people dealing with loneliness or depression,” she said. It’s why the game is available for free to everyone who might need it.

Karambola is free and can be played on PC, phones, or tablets. You can also follow Karambola on Facebook.

The post Help sad fruit people overcome loneliness in a new game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Firewatch is being turned into a movie. Yes, seriously

Well, here’s something. This year’s first-person mystery-adventure game Firewatch is being turned into a movie. For real.

According to The Hollywood Reporter, independent production company Good Universe has teamed up with Campo Santo to develop content for both videogames and feature films. The film adaptation will be their first project together but it sounds like there will be more on the way.

not exactly a prime candidate for adaptation

This is a pretty big deal, and not just because we’re very into Firewatch, but because it’s Campo Santo’s first and so far only title. It’s quite a surprise, really, but Firewatch does star the voice talent of The Walking Dead‘s Cissy Jones and Mad Men‘s Rich Sommer, so perhaps its connection to the film production world isn’t as tenuous as it may first appear.

For those who don’t know, Firewatch follows a fire lookout named Henry, who wanders the Wyoming wilderness investigating strange occurrences. His only means of communication with the rest of the world is via walkie-talkie with Delilah, his supervisor.

How Firewatch will be adapted to the big screen remains to be seen. But it’ll be interesting to see, especially as the majority of the game is spent with Henry, alone with his thoughts—not exactly a prime candidate for adaptation. Good Universe has form, though, with credits including Snowpiercer (2013), Bad Neighbors (2014), and er … My Big Fat Greek Wedding 2.

It seems that Campo Santo founder Sean Vanaman has a lot of faith in the company, too. “When we met Good Universe we were floored by how they recognize, cultivate and produce incredible stories,” Vanaman said. “It’s rare you meet another group that shares so many of your values and makes the process of creating things even more exciting. We can’t wait to see what we make together.”

You can find out more about Firewatch and find ways to purchase it over on its website.

The post Firewatch is being turned into a movie. Yes, seriously appeared first on Kill Screen.

Japan can’t stop depicting war as the cutest thing on the planet

What do the creators of games like I Am Setsuna, Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (2001), Demon’s Souls (2009), and SoulCalibur V (2012) have in common? They’re very familiar with Japanese videogame culture and what kinds of games thrive over there. They’ve got their names on some of the most esteemed games of the generation. They’re “grizzled.” And they’re all raring to make a strategy game!

Tiny Metal, the culmination of their efforts under the studio name Area 34, is a turn-based game that’ll focus on intense tactical combat, backed up by a strong story. It wants to merge the grand tradition of military stories—a genre that has spanned from Ernest Hemingway to that one Bradley Cooper movie everyone wouldn’t shut up about—with old-school Japanese tactics games like Advance Wars (2001).

three anime girls were used as mascots to help bring in new recruits

It’s also characteristically cute: Japan has a history of making its Self-Defense Force adorable, to the point that, in 2011, Japanese attack helicopters had moe-style girls painted on them. And then, in 2013, three anime girls were used as mascots to help bring in new recruits to the Japan Self-Defense Force. Reportedly, the mascots led to a 20 percent increase in new recruits in the Okayama prefecture. The success of these mascots has bred many more of them, all cute, smiling, and happy to be enrolled for war.

The fact that Tiny Metal adopts a similar approach to war is not much of a surprise, then. Its lighthearted approach to war vehicles and the deaths of soldiers—exemplified by everything being “tiny” and cartoon-like—is exactly how Japan tends to depict its combat forces. You can see it in other Japanese war games like KanColle, Panzermadels, and War of the Human Tanks (2012).

Cuteness aside, the hero of Tiny Metal is Nathan Gries, an officer in the Artemisian army that is embroiled in a fierce war with the rival nation Zipang. After his mentor, a colonel in the army, is killed in a transport sabotage, Nathan is deployed to strike back against Zipang. The main conflicts of the game are between Artemisia, Zipang, and the mercenary navy of the White Fangs.

So far, Area 34 has revealed four combat units—infantry, scout vehicles, tanks, and gunships—with more planning to be unveiled as the Kickstarter progresses. The campaign mode will be around eight to 10 hours long with branching missions and unlockable loadouts for the standard turn-based combat. There’s also a stretch goal for 1v1 online play, as multiplayer has been a goal of the team for some time. Other stretch goals include Mac and Linux support, a map editor, snipers, extra campaign missions, and more that’s yet to be announced.

Area 34 has already released a prototype, and says it also has the systems in place to complete the game, so the Kickstarter money will go towards additional content outside of the core assets. The projected release of Tiny Metal is June 2017.

Support Tiny Metal and play the demo via its Kickstarter page .

The post Japan can’t stop depicting war as the cutest thing on the planet appeared first on Kill Screen.

Meadow will let you and friends survive as a pack of animals

Might and Delight, the creator of the Shelter games, has announced its next project, and yes, it too has cute animal families trying to survive the wilderness. Called Meadow, it’s meant to improve upon some of the ideas explored in the two previous Shelter games, as well as add online multiplayer. It’s due out for PC on October 26th.

Shelter 2 (2015) put you in the paws of a powerful lynx mother, letting you explore an open landscapes during various weather conditions. You had to find food, give birth to adorable cubs, raise them, and protect them from vicious predators. Might and Delight wanted to create the same experience with Meadow but also let you wander the wilderness alongside your friends, each of you incarnating your animal of choice.

explore the vast wilderness as a pack

Meadow will feature nine different animals to choose from, then, “with over 60 skins and over 90 expressions and symbols to unlock.” Not only that, those who own previous Shelter games will get bonus content: special emotes to use when communicating with friends and additional animals to choose from. If you own both the Shelter games then you get the most majestic prize of all—ability to play as a bird and soar across the skies.

Other new features in Meadow include the ability to sense the presence of nearby players, and after you meet up, you can either choose to form alliances and explore the vast wilderness as a pack, or become a lone wolf … well, not necessarily, since it depends on what animal you choose, but you get the picture.

Meadow is set for release on October 26 through Steam.

The post Meadow will let you and friends survive as a pack of animals appeared first on Kill Screen.

Smokestacks and metalwork: The industrial horror of videogames

In the most famous scene in Fritz Lang’s cinematic masterpiece Metropolis (1927), the protagonist, Freder, descends beneath the film’s urban dystopia to find a great network of machinery being tended by nameless, uniformed men. Steam columns, the clouds of this underground microcosm, rise and fall all around as the brass soundtrack mimics the percussive thronging of industrial noise. Freder wanders aimlessly through this metallic maze, looking onwards, terrified, at row upon row of men all operating levers in perfect automated symmetry. As the horns reach their background climax, an eruption of smoke and gas tears through the metalwork and throws men clean from their platforms. The word ‘Moloch!” appears on a title screen, and the film cuts back to a gaping demonic face looking upon the chaos. Slaves and workers are filed through the colossal jaws, as Lang confirms his industrial dystopia as analogous to hell itself.

The precedent set by Metropolis—one that explores industry beyond the confines of the factory floor—endures to this day and manifests itself in nearly every form of media. Videogames, films, and music alike all echo the anxieties of the ‘machine’, and strive to preserve the conscious part of humanity we believe impossible to replace. These fears, however, are not unjust, and artists know this all too well. It seems that as humanity edges ever closer toward the singularity, there are a host of creators, visionaries, and designers beckoning it toward us with a hint of glee on their face.

Just what it is that we find so threatening, uncanny, and downright insidious about industrial landscapes and their manifestations is not easily accounted for. It is true that we fear the clinical uniformity of a landscape without soul, depicted in Ghost in the Shell’s (1995) post-cyberpunk iteration of Niihama, where looming pipelines and empty storm drains seem to channel the very essence of life far away from civilization. It is also true that we fear the industrial encroachment on our natural order, a theme touched upon by San Francisco-based studio Campo Santo in Firewatch. The inclusion of a large mesh of wires, antennae, and abandoned comms equipment in the heart of a national park speaks for something far louder than simply a subplot in an already intriguing game. The alien look of the pylons set against a pine backdrop is no mere coincidence: Campo Santo wanted to place at the heart of both the game’s setting and narrative an idea of industry corrupting the romantic image of the American West. The equipment is left unexplained, the anxieties felt in turn by the protagonist and then by us, the player, because Campo Santo wants us to appraise the machinery of modern infrastructure in an environment where it is not so familiar and acceptable.

Inside, the latest puzzle-cum-platformer from Limbo (2010) creators Playdead, takes a more visceral and obvious plunge into the fears only hinted at in Firewatch, and holds up a twisted, broken mirror to a generation now plugged in at the wall.

Hunted and alone, a young boy finds himself drawn into the center of a dark project.

probing into the innate human fear of machinery

This tagline alone hinges on those final two words which, even when separated from the monochrome landscapes captured in the screenshots, sounds distinctively industrial. The word ‘project’ lends the idea of a man-made darkness, a dystopian inversion of the world above ground that Lang had achieved in 1927. Moments from the game see walking lines of distant, automated figures echo the Moloch-ruled hell of Metropolis, and the rainy monochrome conjures to mind the abandoned urban wasteland of David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977). Playdead are probing into the innate human fear of machinery, of robots, of a world run with cogs and grease rather than conscience and creativity. There is something about the black-and-white static that presents the game as if seen through an old CTR television set, back when they themselves sat in the corner of dark rooms in our houses as small industrial giants in their own right. Controlling a small boy in such an environment leaves us as helpless, alone, and afraid as Freder, as Henry from Eraserhead, and just about anyone who has ever walked an abandoned street at night. They want us to feel alone, they want little color because color is familiar and reminds us of things we have no right to remember. Industry, for Playdead, is an idea and not just a machine. It strips us of control, it clones us, and leaves us rummaging around in the dark for the light switch.

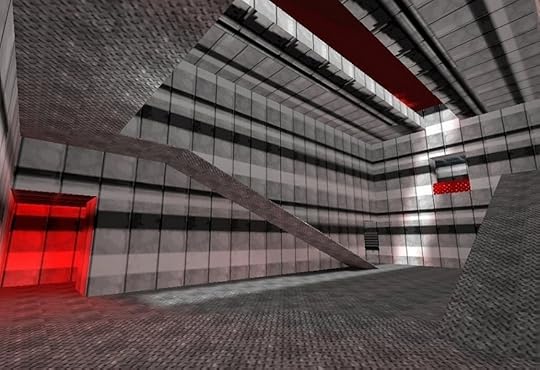

This industrial theme, though, need not be so obviously at play in videogames and film for it to work its subtle horrors. Goldeneye 007 (1997), darling of the first-person shooter genre and multiplayer stalwart, bears its own quiet industrial creepiness. Fan-favorite multiplayer map ‘Complex’ is a winding mesh of walkways, hidden compartments, and air vents. Players stalk empty corridors, hear the footsteps of their unseen assailant, and often fall prey as they blend into the corrugated backdrop. ‘Facility’ borrows the film’s opening factory blueprint for its map design, and hunting each other between the tall silos and across empty factory floors adds a psychological aspect of anxiety and fear to the cult classic. What Goldeneye 007 achieved through its now dated, blocky, nondescript map designs was a strange and uncanny pixel rendering of a familiar industry. Transposed into the basic graphic style allowed for by the Nintendo 64, the spaces become distorted and eerie. The ominous soundtrack with its iconic pipe-ringing sound effect made for an experience entirely unlike the modern FPS multiplayer arenas. You feel more alone on Goldeneye than you could ever possibly feel in today’s big shooters, and that’s because the industrial designs of the game, whether intentional or not, achieved a surreal and uncanny effect.

This nuanced evocation of unease and terror was taken in 2015 by Duende Games and turned into an all-consuming meditation on Brutalism and its quasi-industrial rendering of the world around us via their free game Tonight you Die. In the game’s opening, a letter appears on screen and states those three titular words before falling to the ground. Ahead of the character is a fuzzy, static-shrouded graveyard of Brutalist tower blocks and benches, everything asphalt and lifeless. You walk to the sound of a droning soundtrack that rises and falls in random places, interrupted only by the crackling electronic buzz of the various street lamps spilling their monochrome light onto the floor. What is this ‘game’? More importantly, what is the point? A procedurally-generated maze of concrete monoliths and their darkened eaves isn’t what most would readily embrace as a ‘game’, but that’s because it’s not trying to be. A game traditionally suggests some element of lighthearted fun is to be had, but that is admittedly scant in a game that tells you in its opening seconds that you will die that evening.

Duende Games evoke the poverty of Stalinist Russia, the monotony of Metropolis, and the lifeless expanses of Eraserhead in an artwork like no other. It orders you to use headphones, and begs to be played in the dead of night. Industry in this game is less about coiling wires and more about the possibility of nothing beneath the surface. The fizz of lampposts at twilight is as lonely a sound as I’ve heard in a game, and Duende knowingly choose that very noise as the only audible relief in a game of despairing quiet. Why is electricity running in a place where no soul walks save your own? Why do no lights shine on the upper landings of countless towers yet guide you through abandoned courtyards? There is no need for any infrastructure in such a world, and that is where this game’s intriguing horror lies. The slow revelation of isolation is hastened with each doorway crossed, until the player closes down the game and turns on a light and sighs quiet relief.

the possibility of nothing beneath the surface

Innate to the experience of creeping menace in Tonight You Die is its varied ambient soundtrack, sounding part Eno and part Lynch. Music has asked the same questions of our place in an automated, hyperreal world for just as long as videogames and films, and its findings are often even more haunting. Post-rock outfit Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s eschatological debut F♯ A♯ ∞ (1997) begins with an eerie audio narration from an abandoned screenplay, describing a city brought to ruin.

The car’s on fire,

and there’s no driver at the wheel.

And the sewers are all muddied,

with a thousand lonely suicides.

What follows is a description of a city burning bright with the fervor of apocalypse, and an infrastructure brought to ruin. The music evokes a landscape every bit as bleak and lost as those above, but does so through its atmospheric sorrow and elegiac strings. If Mirror’s Edge (2008) showed us a city during the apex of a global infrastructure, then Godspeed shows us that same city when all else has fallen to ruin. I envision the same cityscape from Tonight You Die when listening to this album—it’s nearly impossible not to have been exposed to both. I am alone when I hear it; I am listening to the aural equivalent of Revelations.

It’s all around us. Everyday. The smokestack on the horizon, the pylon in the backfield, the plug socket in our walls. Everything hums and whines with the flow of our consumer experience, working its volts to and fro like Lang’s enslaved. The above media are only one side of of the proverbial polygon, each adding its own little take on a world run by machines. Studios like Campo Santo, Playdead, and Duendo are not content, however, with sitting by and letting such things slide. They want to show us the ghost in the machine, they want us to be possessed and yet witness the possession. But above all else, they want to warn us.

The post Smokestacks and metalwork: The industrial horror of videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 26, 2016

BalanCity asks you to build the world’s most misguided city

BalanCity is a diamond in the rough. The menus and presentation of the game leave a lot to be desired, but the actual game, the act of balancing hospitals atop skyscrapers without accidentally sending your whole city into the ocean, is about as compelling as city-building gets.

It’s no SimCity (2013), but no one seems to have told BalanCity that. Hence it tasks you with the typical challenges of a city-builder. You have to keep your approval rating high or people will protest in the streets of your unbalanced city. And you’ll need to keep your emergency services working to put out the fires, rescue people that’ve fallen out of your leaning towers, and repel the definitely-not-Godzilla as it attacks your city.

It is perfectly okay to release a panicked shriek

Building a city on a pivot is hard enough without the range of disasters that can befall you. Example: It might turn out that you need to bulldoze your city blocks because you’ve built them incorrectly, or because they’ve toppled over. Doing so might then upset the weight distribution and topple everything into the sea. It is perfectly okay to release a panicked shriek in these moments.

You get what you see with BalanCity. Despite the selection of missions and variety of different buildings on offer, once you’ve got the gist, it doesn’t change up too much. You’ll get hit with earthquakes, a meteor strike, or even attacking aliens as you progress, but you’re always trying to stack skyscrapers without everything falling into the ocean—never anything else.

That said, when all the systems move in place, it can be magical for a few seconds; you’re trying to right the wavering city, while a police helicopter speeds off to quell a protest by hosing the entire area with pepper spray. It feels like chaos balanced between your fingers. Then it all falls over.

BalanCity is on Steam . You can buy it right now. Find out more on its website.

The post BalanCity asks you to build the world’s most misguided city appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers