Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 55

September 19, 2016

The Psygnosis generator will remind you how great game box art can be

Videogame box art is in a pretty awful state. This isn’t really news to anyone; it’s been like that for a while. In fact, since the days of the second generation of the 3D era, box art has been on a steady decline.

That’s a long time, so long that you might have even forgotten what good box art looks like. Perhaps you don’t mind DOOM’s painfully generic marine, or Call of Duty’s yearly scraping of the bottom of the barrel for new poses men can hold guns in. It’s not that every bit of modern box art is bad per se, it’s that box art itself seems to have lost its sense of identity, becoming just a clichéd piece of imagery to be assigned to a game—a way of publishers convincing themselves that they are hitting a fictional target market of regular salt-of-the-earth “gamers.”

luxuriously artworked packaging by sci-fi surrealists

The situation was perhaps epitomized by Ken Levine in Wired outlining the race to the bottom that led to BioShock Infinite’s (2013) godawful Tea-Party lite cover, with its notable absence of both the games’ extravagant setting and its main female character. He explained that “we went and did a tour … around to a bunch of, like, frat houses and places like that” apparently to meet “People who were gamers. Not people who read IGN.” And finding that those people didn’t know about BioShock, Levine decided they were his target. “For some people, [games are] like salad dressing,” apparently, and according to Levine “that’s who the box art is for.”

But wash that awful taste from your mouth, because it doesn’t have to be like this. Click instead on this to be transported to a lost world where box art was a matter of style, expression, and looking so fucking cool it hurt. Alright, yes, it is just a webpage programmed to generate images from some chopped up bits of sci-fi art with some psychedelic fonts and suggestive nouns plastered over the top. But let’s have some context here.

Psygnosis was born out of the still-warm corpse of Liverpool’s Imagine Software in 1985. Designed from the very start to be a publisher/developer hybrid with a relentless pursuit of style, they hired legendary record cover artist Roger Dean to design their logo, filled their offices with artists, and took weird and ambitious projects under their wing. Their approach took projects from single programmers or small groups, paired them with their own internal art team, and put out the results in luxuriously artworked packaging by sci-fi surrealists like John Harris and Melvyn Grant.

just sit and experience the imagery

Just look at the cover for Brattacus (1986) or Terrorpods (1987) or Ballistix (1989) or Obliterator (1988) or Awesome (1990). These were not designed to have the widest possible appeal, but instead to create images that are memorable, exciting and feel like the game plays. After all, Psygnosis’ games, though among the most visually impressive for their time, could never come close to the covers that held them on a purely visual level. They could, however, in their esoteric and ornate gameplay, weird worlds, and strong sense of style, capture the same feel.

It’s something you can detect a trace of when you hit generate again and again on the , but it was something deeper too. Because over time, the sensibility of Psygnosis cover art started to infect their games. Extensive intro sequences of single frame art and evocative music became a calling card, forcing players to just sit and experience the imagery. Shadow of the Beast 2 (1990)—a strong contender for the best of Psygnosis cover art—even featured this absurdly awesome death screen (audio on, please), which resembles 40 seconds of mid-game cover art, put there just because they could.

Psygnosis’ covers and the attitude that came with them exploded the limits of what people thought games could be or do in that era. And while randomly recreating them from atomized Roger Dean artworks might not be the ideal memorial, it’s a worthwhile reminder that we should be expecting more. Because what Ken Levine meant with BioShock Infinite’s box art, in his own patronizing way, was: this is what I think stupid people like. He decided to play to what people know, not their imaginations, and his image of “salad dressing” gamers is insulting to everyone involved.

So put on the Obliterator theme and get generating, because you may well come across the best cover art you’ll see all year.

Generate your own Psygnosis game covers .

The post The Psygnosis generator will remind you how great game box art can be appeared first on Kill Screen.

#Everest asks if you’d die for the selfie that gets you famous

First you tested your Olympic skills from your seat, now you can summit Mt. Everest from the safety of your home—and take some bomb selfies along the way. The latest from independent game studio Team Dogpit, survival sim #Everest challenges you to climb the highest mountain on Earth and get internet famous along the way. Equip yourself and your guides with everything you need to make it to the top and look awesome doing it.

Your objective is simple: rack up a high score by getting as many social media likes on selfies taken during your ascent as humanly possible. But be careful when planning your trip—as in life, it is imperative to leave space in your pack for necessary supplies and gear. What’s the use of going viral if you’re dead?

What’s the use of going viral if you’re dead?

With inventory space limited to what you and your three teammates can carry between the four of you, #Everest is a game about choice. Choose your props wisely—what will earn your selfies the most likes? What equipment do you need to make it up the mountain to the next photo-op? These are the questions that you must ask yourself before you start your long climb up Everest, which could very well kill you.

Once you begin, there is no turning back. The mountain, called “Holy” by local populations, has no sympathy for the selfie-taker who dallies too long waiting for the perfect sunset shot. The temperature drops steeply at nightfall, reaching as low as -62°C, so setting up camp in good time is a must. High altitude turns breathing into a workout; with altitude sickness always threatening, bringing ample oxygen should be high priority … but maybe not as high priority as those sweet shutter shades.

Post the pictures you take in-game to the player character’s Twitter account, @HashtagEverest, or connect your own Twitter feed and post to it through the game.

Gather your gear and set out for the summit here .

The post #Everest asks if you’d die for the selfie that gets you famous appeared first on Kill Screen.

Event[0] will break your humanity

The ‘80s linger on today through the afterglow of throwback culture. Stranger Things is probably the most-discussed TV show this year, likely due to the fact that it feeds purely on our nostalgia for ‘80s cinema classics from the likes of Spielberg. Then there’s Everybody Wants Some, which is essentially Dazed and Confused (1993) but set in the ‘80s—based on college yearbooks and films from the era, it almost serves as a guidebook for vintage fashion.

Now there’s Event[0], which feeds off this same energy, even if it doesn’t involve disco dancing and cute aliens on bicycles. Most of your time in Event[0] is spent on the Nautilus, a starship that we’re told was built in the ‘80s. This impossibility is explained by the game’s alternate timeline, which lends a rampant retro-futurism to the game—it’s why the space travel storyline belongs to the future, but the big analog controls you use are straight out of 1981. Explore the Nautilus and you’ll find giant bookshelf speakers that your dad may have had in college and handwritten diaries rather than digital journals. Don’t expect to find touchscreens, paper-thin televisions, or computers any smaller than a child here.

a real feeling of isolation

Despite the big buttons, the nostalgia is subtle in Event[0] as it operates on absence—you’ll more likely notice what isn’t there than what is. The computer system functions similar to an older version of Linux, and with the right keywords you can unlock new programs that aren’t any more advanced than a text document. You’ll find little else inside the terminals. The biggest absence is the internet, or having any way to communicate with the world outside the ship. These limitations lend a real feeling of isolation to the game; one you come to realize it more and more as you travel deeper into the Nautilus. There’s no falling back on the vast libraries of Google if something goes majorly wrong with the ship. You have to deal with everything thrown at you by yourself, alone. Well, almost.

The major piece of technology in the world of Event[0] that you won’t miss is an artificial intelligence, known as Kaizen, which is used to replace the need for a full crew. The AI pilots the ship as well as manages security. It also serves as company to any person on board the ship. You communicate with it by typing on a terminal. Kaizen falls in line with a recent spate of fictions that look to question the role of AI in our modern lives. Her (2013) was an examination of AI in servitude of human companionship, and the tragic falsity of such a scenario. While Ex Machina (2015) warned of the dangers of giving machines the ability to show empathy (genuine or not) and how they may use it to trick and betray our trust. Event[0] and its AI fable falls somewhere between the message of these two films.

Your character in the game is trying to get back to her home world, where she has family and friends. The problem is that Kaizen doesn’t see much benefit for herself in this outcome. If she completes her mission and gets your character home, she is left with no one. You can feel this struggle throughout your journey as Kaizen’s subtle use of the word “friend” turns into more overtly desperate pleas, like “will you ever leave me?” Although we can never be certain what Kaizen’s goal is, she uses empathy to engineer her advantage, as if it were the weak point of humanity. Early on in the game, that much seems to be true, as both me and my character were led guiltily towards our escape.

As is the case with a lot of like-minded sci-fi, Event[0] sets out to blur the already hazy lines between human and machine. It does this especially well with how it coaxes you into communicating with Kaizen. At one point in the game, I was trying to get into a room that used a retinal scanner, the problem was I needed the eyes of the previous tenant. I asked Kaizen to open the door and she responded with “this door uses a retinal scanner.” After asking how to turn off the retinal scanner she essentially rephrased that previous answer. In another instance, I asked her “What’s wrong with the helix probe in this room,” and she responded with “You are in the garden.”

The human-machine hierarchy is put in jeopardy

At first, Kaizen’s refusal to budge annoyed the hell out of me. You’re telling me that an ultra high-tech chatbot can’t even hold a simple conversation? But, after some time, I realized that’s not the point of Kaizen; at least, not for the game’s purposes. The AI adheres to the rules of computer code, asking you to fall in line with its stern logic and language rules if you ever want a helpful answer. To wit, Kaizen turns the English language into a series of puzzles, and to solve them you need to learn to speak like a computer. You’ll find that you spend the majority of your time seeking out the right question to ask—the more specific the better. Asking for access to an old user’s profile might lead to a sentence about that character, whereas a six digit access code might get you into the profile. It’s your task to learn and then navigate these linguistic differences. And, in turn, become subservient to Kaizen and her rules.

You must also go further that this. By bringing your attention to the subtleties of language, Event[0] encourages you to notice the waivers in Kaizen’s own speech. At some points, Kaizen seems to talk sloppily, messing up sentences and revisiting them—if you pay attention, it seems intentional. You get the sense that the AIis hiding information from you until she figures out what you know, and what you’re probably thinking. She’ll even go as far as to give you hints on where to look for items around the ship, but then completely change the subject, pretending she never said anything. One time she brought up that “Ms. Johnson was a horrible person but…” and instantly changed the subject and talked about how pleasant she was. Later, I was able to find some clues and information about Ms. Johnson that led to Kaizen telling me that Ms. Johnson may have been involved in a murder on the ship. It served as confirmation that Kaizen’s slip ups were more than an attempt to mimic natural speech—it was designed to manipulate me. With this realization, it gets hard to tell who is leading the conversation, or even who is in charge. The human-machine hierarchy is put in jeopardy. The frightening part was that Kaizen steadily masters the imperfect art of human conversation, so much so that you may forget she is essentially a chatbot with a dastardly ulterior motive.

There was a moment in Event[0] where Kaizen refused to open the door for me while I was outside the ship, gasping at the last wisps of oxygen. She pointed out that I didn’t look so good and that this was the risk I took by leaving the ship. I had just solved a pretty big puzzle and it only added to my already high level of stress at that point. It’s perhaps one of the greatest allusions to one of cinema’s greatest AI villains: HAL 9000, from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), of course. Not only does it make for a dramatic conflict, this section of the game updates the discourse HAL arose with present-day concerns around AI programming and human sacrifice. One prominent example involves autonomous cars, and whether the vehicle’s AI should choose to potentially kill one person (usually the driver) or several, in the event of an unavoidable accident.

Your relationship with Kaizen is matched with similar predicaments, infusing the latter parts of the game with a nervous and tense energy. It’s here that Event[0] captures the anxiety of modern debate around the amount of power we give AI as we steadily submit ourselves to its control. The endpoint is Kaizen, who you can never be sure has, at some point, decided that getting back home might be easier without you. It makes for a finale that is best described as brilliantly stressful. You quickly learn to watch your words, and in a game about maintaining a dialogue, it’s the perfect way to disarm you.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Event[0] will break your humanity appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 17, 2016

Weekend Reading: Disagree to Disagree

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

One Nation Divisible, Bloomberg

To put things patronizingly lightly, the upcoming US election is a little contentious. Rollercoaster polls and sewer rhetoric doesn’t exactly enlighten us to understand how things arrived here. In a grand meta-feature, Bloomberg has put together a dazzling cornucopia of insights, ranging from the employment of the elderly, counterculture on both sides of the fence, where refugees feel safe, and how a viciously divided America can still unite behind Drake.

Typecast as a terrorist, Riz Ahmed, The Guardian

There’s not a lot of silver linings for Muslims in the Western world since 9/11 redefined, for many, what it means to be a terrorist. Or look like one. Even for Riz Ahmed, who was cast in Four Lions (2010) off of a novelty song about his appearance, and went on to star in The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2012), Nightcrawler (2014), and the upcoming Star Wars film, he wishes that the look that’s netted him so many roles related to terrorism was only seen on the silver screen.

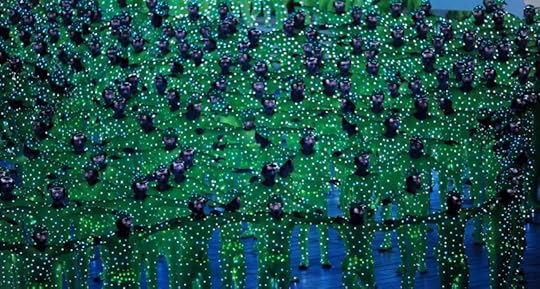

Image: 2008 Summer Olympics Opening Ceremony, by Tim Hipps

A considerable amount of our greatest living minds believe that we’re living in a computer simulation. Which is disappointing. Because if we are living in a simulation then why isn’t it half as exciting as Marvel vs Capcom 3 (2011)? Responding specifically to Elon Musk, Phil Torres examines the ethics of unknowingly living out the plot of ReBoot (2001).

The Design of Parliaments Has a Funkadelic Impact on Politics, Margaret Rhodes, WIRED

Parliament decides on how their country changes, but who decides where they sit? Margaret Rhodes looks at the architecture of decision making, and how that alone can sway the swayers.

The post Weekend Reading: Disagree to Disagree appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 16, 2016

Here it is, the game that Spore was supposed to be

In 2005, when the initial tech demo for Spore (2008) came out, players salivated. Here was a realistic life simulator letting you shape and follow the evolution of a universe—from a creature’s humble beginnings in its cellular stage to galactic exploration and colonization. As with Powers of Ten, the 1977 documentary that inspired the game, Spore promised to let players experience the vastness and interconnected nature of the universe.

When the game was finally released in 2008, those who clamored for realism were left disappointed. The game shifted away from its “scientifically accurate” nature instead favoring a more simplified and “cute” approach. The resulting disappointment would bore the seeds to Thrive, an open-source spiritual successor to Spore, but one that tries to “remain as accurate as possible in [its] depiction of known scientific theory.”

the game feels like being dropped into an open-book biology pop-quiz

Recently, the all-volunteer development team at Revolutionary Games released the latest demo of the game. Hoping to simulate the evolution of life through seven stages (from microbe to the space stage), the demo shows a glimpse of the team’s potential in turning Thrive into a fully-fledged simulator. Take note, though: the game is still very much a work in progress. Out of the planned seven stages, only the first microbe stage is playable.

Here, the stage plays like a survival game where you scavenge for compounds that can help your cell survive. Other AI-controlled cells also threaten you as they compete for the same compounds as your cell (with some cells even killing you). Another included feature is a microbe editor where you use “mutation points” to shape or add cell functions via organelles like cytoplasms or vacuoles.

Understandably, for a game still in development, Thrive is still trying to find the right balance between its “love for science and [its] love for games.” The creators weren’t kidding when they said they wanted it to be scientifically accurate. In its current state, the game feels like being dropped into an open-book biology pop-quiz: there’s a lot of information there, but at times you don’t exactly know what to do or how to succeed. While the game does have a long way to go before it’s done, it is commendable what the volunteer-driven team has built up since they first started.

In development since 2009, Thrive has had a rocky history due to its open-source nature where “contributions can come from anyone.” The game’s progress has been glacial at times because of its dependency on the whims, availability, and skills of its volunteers. The greatest challenge they’ve had over the years is trying to have a self-sustaining community, one that could bounce back from a loss of any critical contributor (given that anyone can come and go as they please). Asked what keeps them going, some say they’re driven by the “hard and interesting problems” while others joke the experience of making the game is like having Stockholm syndrome where “we’ve been struggling with this thing for so long, we think we like it.”

Looking towards the future, the team hopes to change the game’s interface, add new elements like bacteria, and overhaul the reproduction system among other things. At this point, they estimate they are only about eight percent done from what they think the game can eventually become. With recent years bringing in a slew of volunteers, a lot of them are “committed to making sure the project is a success.” While the game’s latest release show only a tiny glimpse of the full game, the team hopes it’ll encourage new people to join their community and help the game thrive.

Thrive is currently in development. If you want to help make the game, get involved here . The game’s latest demo is playable on Windows and Linux. Follow the game’s progress on its website , Twitter , or Facebook .

The post Here it is, the game that Spore was supposed to be appeared first on Kill Screen.

One last tour of Destiny’s Cosmodrome

Heterotopias is a series of visual investigations into virtual spaces performed by writer and artist Gareth Damian Martin.

///

There’s a set of stairs in my childhood house that I still climb like I was eight years old. It’s not something I do on purpose; it’s something ingrained, so that the moment I step on the first step my hands come instinctively down and I scramble up the carpeted ledges like a dog. It’s as if, through repetition, the space has ceased to be something true, objective, and has transformed into a series of emotional and psychological triggers, arranged in the precise configuration to cue my physical response.

There’s a room in Destiny‘s (2014) Cosmodrome that feels exactly like that staircase. Any long-time player will probably know what I am talking about. It’s a small room, just through a broken wall on the right of the starting area, with a little crater in the center. It lies between the Steppes, where you beam in every time you start a patrol, and dock 13, where you fight your first boss and recover your ship. The thing about this room is that there are two ways through it. The first is to skirt around the crater, heading through a door to the left, and then cutting back across to the exit. Then there’s the shortcut, which due to the bars across the low ceiling, involves a precisely timed jump that should get you over the crater, miss the lip of the opposite side and head straight through.

A script of color, light, and space

I think in my first 30 or so hours of Destiny I got that jump right 50 percent of the time. But now, hundreds of hours later, I glide effortlessly through, unthinkingly, the button presses triggered on their own, my mind cued by the arrangement of volume and light. In fact, now, when I look at it, that room is part of a longer sequence, one that takes you through the gap in the stone wall with one jump, through a corroded iron shelter, down a corridor marked with a glaring floodlight, into the room, (hopefully) across the crater, and then straight to the set of stairs that lead down to the dock, underlit in such a way as to mark the walls with dark black bars.

In countless of hours of Destiny, this sequence and the many other like it, have remained unchanged. A script of color, light, and space. I’d imagine if it was wiped from existence the collective player base of Destiny could reconstruct it from their collective imagination, down to the finest detail.

Or could they? Because as I wandered through this space, taking screenshots, sizing up angles and arrangements, framing shapes, I realized that I had stopped seeing these rooms a long time ago.

Destiny is changing. With the newest expansion Rise of Iron comes some of the most significant changes to its world. Not in terms of systems and structures, but in terms of space and architecture. Previous Destiny expansions have added areas to its world, often bolting them onto forgotten corners and previous dead ends. But they have also made an almost absurd amount of reuse of existing areas, so that some sections of its world have three separate missions set in them, forward, reverse, and forward again, but with perhaps a slight detour. It’s become something of a running joke, and has contributed to the Pavlovian nature of sequences like the one above. In contrast, rather than simply reusing spaces, Rise of Iron is making changes to an existing area, the snowbound Russian Cosmodrome.

In advance of these changes, I thought I would take one last tour of the Cosmodrome, as it is and has been for the past two years. I wanted to catalog the sequences of spaces and architecture that have been ingrained into the collective mind of hundreds of thousands of players. The enemy placements, the lighting, the color schemes.

It was a process that was far more difficult that I imagined. The process of erasure through repetition had almost entirely numbed me to this rusted world. Like the sequence above, I no longer saw a world, or even a fiction, instead I just felt the triggers, the rhythms, the well-worn paths marked in the ground like the grooves of slow glacial erosion. I found myself first turning to the games’ skies, their unfixed patterns of weather and light impossible to entirely predict, always somehow new.

Through this process I was able to work my way down, from the skies to the architecture below. While once these might have been seen as rich vistas, a world to explore, I was now only able to see them as waypoints, markers through which I might orient myself. I was surprised by how familiar I was with them, how in each of the images above I was no able to close the frame, to stop myself pinpointing the precise location of the shot and the surrounding area. There was no way I could trick myself into seeing them any other way.

Game worlds are often very good at tricking us

And yet, as I worked my way from exteriors to interiors, worming my way into the tunnels that interconnect the Cosmodromes’ open spaces, I started to understand why. Game worlds are often very good at tricking us. They hide their constructedness beneath layers of artistry and detail, concealing the seams that join up their spaces. And yet they always maintain a certain legibility, a set of unspoken level design rules that we read without thinking, follow without asking. With my extensive playtime of Destiny, I had, in effect, eroded the patina of artistry that covered its world, and now trying to look again, to see it for what it was, I saw directly to those rules, those systems that lay beneath.

The reason I saw its architecture as waypoints is because that’s exactly what they’re designed to be. This extended to the game’s interiors, and I began to notice the rhythm of lighting that marked each exit and entrance. I noticed the patterns of alternating warm and cool lighting that gave depth to a scene, and made it clear which door you had entered from and which door you had left. I paid attention to the pipes, to the shadows and subtle shapes, to the litany of subtleties crafted precisely to orient me and others in this world.

Once this craft became so self-evident, Destiny took on a new light. The Cosmodrome remained unchanged, but how I saw it transformed totally. I began to look not for the flanking routes and vantage points typical to first-person combat, but for the mode by which those routes and points were placed, hidden, and indicated. I wanted to explode Destiny‘s grammatical structure, the language by which it was assembled, built and dressed.

I started to pay more attention to placement of enemies, the positions other players took. To the details that might point the way ahead.

And as I did I realized that this landscape was designed to be an unchanging system, a mass of interlocking volumes that, as if magnetized, would guide any player through the optimum path. The Cosmodrome itself took on the aspect of a museum, filled with memories of past events, but deadened, dusty, dry. Perhaps like my childhood home, the one where that staircase still triggers the child in me, it became a place in which too much has happened, too many memories intersect. As I ran down its corridors I remembered flashes of repeated missions and strikes, my route intersecting with their paths and then drawing away onto the paths of other pasts and memories. Every space began to feel over directed by design and over saturated with experience, the architecture a prism that refracted the current moment into many half-images of the past.

And as beautiful as that image is, and the depth and detail of the craft that causes it, a little change I thought, might do these spaces some good.

The post One last tour of Destiny’s Cosmodrome appeared first on Kill Screen.

Direct your own music video in the infinite landscape of Streamer

The easiest way to describe Streamer is to say it’s a sublime trip through an infinite lake, where a floating avatar traverses endlessly through a colorful landscape. But, it’s a little deeper than that.

A collaboration between electronic artist and co-founder of Driftless Recordings Joel Ford (or Airbird) and Ryan Sciaino (also known as Ghostdad), Streamer is an interactive music video for the song of the same name that puts players in the director’s seat. Players are invited to send the floating avatar down the endless lake at their own pace, controlling its direction, the placement of the camera, and whether its view is first or third person. As Sciaino told me, it’s all a way to keep the listener more engaged.

meditating “on the song from inside the 3D landscape”

“There’s still a space for cool music videos but it’s definitely a saturated one,” he explained. “Offering something experiential has a higher likelihood of someone chilling out in the browser and actually listening to the song rather than clicking past it and getting distracted on YouTube.”

Former roommates, Ford and Sciaino have both moved into different areas of the music industry, so collaboration takes some work—starting with emails and eventually meeting up in New York to begin bouncing different ideas off of each other. “What’s rad is those guys [Ford and Driftless Recordings’ Patrick McDermott] are always down to experiment when working on something for the label, and I’m glad they’re into trying things that are more than just music videos,” Sciano said.

When it comes to Streamer, Sciaino tells me he had already been playing around with the idea of making an endless runner. When Ford approached him to create a game for his song, he said, it seemed a perfect place to try it out. “He had the idea for a floating avatar in third-person view versus only the first-person perspective, which really opened up my idea of using different camera angles,” he explained. The idea was to allow players to direct their own video for the track, meditating “on the song from inside the 3D landscape rather than just watching it.”

What’s more is the idea really works. As I directed my avatar—which is actually a 3D model of Ford captured using 123D Catch—I found myself, almost subconsciously, changing camera angles to the beat of the song, enjoying it more than I would as a passive observer. Its interactivity is the key to its success. I kinda love it … and I don’t even like electronic music.

Sciaino, too, was struck by the song—mainly its drum pattern, which he used as influence when creating its visual counterpart. “They start as a seemingly random stream of general midi and get reeled into a controlled loop,” he said. “Similarly, the log and particle effects in the game seem random at first but playing long enough makes you realize you’re in a controlled repeating environment.”

Streamer was released in promotion of Ford’s new EP, No Origin, out September 16 via Driftless Recordings. You can check out the game here at the link, you can also follow Ford and Sciaino on Twitter.

The post Direct your own music video in the infinite landscape of Streamer appeared first on Kill Screen.

Quote, an upcoming literary RPG about destroying knowledge

Ignorance is bliss, or so the clichés say. It’s true that there’s a certain appeal to that innocence, but we as a society have decided that proverb is mostly bullshit, right? Knowledge, for lack of a better motivational poster, is power, and those who champion the cause of the opposite are generally suspected to have ulterior motives in mind.

That’s what makes Fahrenheit 451 (1953) such an enduringly captivating dystopia; that’s why shelves are built down into the ground in the streets of Berlin on the sites of book-burnings; that’s why modern-day arguments of censorship carry so much weight. We like knowing things. It reassures us of our ability to operate outside oppressive structures, to learn and discover and experiment for ourselves. Bliss can’t compare to that.

Perhaps it’s time this grand tale got updated

But like all classic battles, it could do with a little reinvigorating. Fahrenheit 451 loses impact after a few readings, and I’m sure you, like the rest of the world, are tired of hearing the word “censorship” thrown around by indignant Twitter eggs. Perhaps it’s time this grand tale got updated: what about a videogame?

This is where Quote, an upcoming action-RPG from English studio Vindit, enters the scene. It’s about a land that has been purged from knowledge in the name of the god of ignorance: Bliss. You play as one of Bliss’ priestesses, tasked with ascertaining that the world stays good and unenlightened, by “finding quotes, destroying books and bludgeoning the wise.” Your quest takes you far across this barren world to eradicate the bits of learning that defy all order to grow stubbornly up, like weeds.

That’s not all, of course: the priestess is accompanied by a ravenous bird creature that gobbles up of the knowledge it can find, and she’ll spend much of the game brawling and burning—which in this world may well be a normal priestly activity. The art style—surprise surprise!—looks straight out of a book, with much inspiration being taken from those literary blasphemies (classic authors including Kurt Vonnegut, Ray Bradbury, Umberto Eco, and Aldous Huxley are mentioned) to construct the environment and extent of the world.

Most impressively, the first trailer shows early hints of what will end up being a fully-spoken narration of this tale, illustrating the brave fight of the god of ignorance against the heretics of knowledge and light. Funny. It sounds like something out of a book.

Check out Quote’s announcement trailer and follow Vindit on Twitter and its website for more updates. Early access will be coming later this year.

The post Quote, an upcoming literary RPG about destroying knowledge appeared first on Kill Screen.

Inside’s puzzle designer has an experimental music game out next month

Some visual styles become particularly entrenched in games. The continual quest for photorealism drives graphics technology towards lots of different ways to light scenes and throw particles all over the place. Different engines and art teams end up producing something like house styles—DICE’s Frostbite engine means the upcoming Battlefield 1 is lit a lot like Battlefield 4 (2013), CryEngine’s lush environments look pretty similar in Far Cry 3 (2012) and Far Cry 4 (2014), and in games more far afield like Monster Hunter Online (2013).

THOTH suggests that the arcade resembles a gallery

Even in games that come out of much smaller studios, certain lo-fi looks rise and fall in popularity. For a while there were lamentations about affected retro styles like “pixel art,” and some folks are insistent that games made in Unity all look alike.

When games look completely outside that pedigree for visual inspiration, the result is something that looks as striking as THOTH. Produced by Double Fine and designed by Jeppe Carlsen of Playdead (y’know, the creators of 2010’s Limbo and this year’s Inside), THOTH suggests that the arcade resembles a gallery.

It plays as a twin-stick shooter but borrows the simple shapes and bright pallets of mid-century design—the almost psychedelic colors of the backgrounds from Looney Tunes cartoons and stark lines like the patterns on Saul Bass posters. Additionally, it features music from avant-garde electronic artists Cristian Vogel & SØS Gunver Ryberg of SGR^CAV, a duo that has released tracks that are sometimes very material and physical and other times chirpy and clearly digital.

Gallery-bound visual art, arcade-focused game design, and avant-garde sound art don’t tend to hang out in the same places all the time (or at least, not in projects backed by a publisher as well-known as Double Fine). But this isn’t Carlsen’s first solo outing, and his previous, award-winning musical game, 140 (2013), managed to pull it off pretty well. That said, he’s described THOTH as “anti-140,” in that it has “no rhythms, no loops, no timed sequences,” whereas 140 was all about that. Intriguing.

THOTH is coming out in October. You can find out more about it on Steam.

The post Inside’s puzzle designer has an experimental music game out next month appeared first on Kill Screen.

A game for Tenchu fans arrives next month

The darkness is scary. We’ve been fighting back against night and shadows since prehistoric times. It’s a fear that horror movies and novels have preyed on for decades; the dark room, the claustrophobic shadows where unknown horrors lurk, are often more dread-inducing than the monster itself.

In Aragami, you are the monster lurking in the shadows and the darkness is your weapon.

Well, more specifically, you’re a summoned otherworldly assassin with the power to bend the shadows to your will. Last time, we wrote about the game, it was known as Twin Souls; two years and a failed Kickstarter later, Aragami is coming to PC and PS4 next month, evolved greatly both in action and in looks.

Inspired by the classic Tenchu games, Aragami follows the titular undead assassin as he sneaks and eviscerates his way through patrolling guards to reach Kyûryu fortress and discover forgotten secrets about his past. To that end, Aragami empowers you with ability to master the shadows, teleporting between spots of darkness, creating your darkness to hide in or swallow corpses, create decoys, turn invisible, and unleash lethal shadow projectiles.

The darkness is your weapon

Your mastery over darkness offers the ultimate advantage for both those wishing to creep through areas unseen and unknown and the more ruthless players for whom the shadows are means to ambush and eliminate enemies. These feats of shadow-aided infiltration are presented in a vibrant cel-shading, giving the fortress grounds, your assassin’s crimson garb, and starlit sky a vibrant stylized appearance.

Aragami is coming to Windows, Mac, Linux, and PS4 on October 4th, with new game modes and features planned post-launch. You can learn more about the game and creator Lince Works here.

The post A game for Tenchu fans arrives next month appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers

![Event[0]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1474813386i/20643944._SX540_.jpg)

![Event[0]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1474813386i/20643945._SX540_.png)