Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 58

September 13, 2016

The Last Guardian’s development cycle now overlaps the Obama administration

Three yards from the finish line, The Last Guardian has been delayed again. Put down your torch—it’s still within grasp. Just a bump from the end of October to the beginning of December, an amount of time that seems so puny at this point it barely feels worth getting upset about. It just means that The Last Guardian won’t be available before Halloween, before Thanksgiving, or before the US presidential election. Oddly enough, President Barack Obama was sworn in the same year that The Last Guardian was announced, mere months before. Of course, the game was being worked on before it was shown to the public, meaning that The Last Guardian’s development cycle will now overlap the entirety of Obama’s administration.

The Last Guardian has been delayed a fair number of times, and speculation that the project had been cancelled emerged when the game was unheard from in large pockets. Those rumors were further spurred in 2011 when Fumito Ueda, founder of Team Ico, departed Sony, though it would be revealed he had remained involved with the game. The Last Guardian was originally created for the PlayStation 3, some fans claiming that’s why they bought the system. At E3 2016 it was revealed to still be set for release, though coming to the PlayStation 4 instead, given that the platform had been on shelves for two and a half years at that point.

rumor spread that Jeff Goldblum had fallen to his death

The Last Guardian was announced during E3 2009, alongside Halo: Reach (2010), New Super Mario Bros Wii (2009), the PSP Go, and The Beatles: Rock Band (2009). If you were born on the day that The Last Guardian was announced, you would now be seven years old. You would have just entered grade school this month.

A lot has happened during The Last Guardian’s development cycle. Starting with the contemporary cultural metric of time, celebrity deaths, we lost David Bowie and Prince, obviously, as well as Amy Winehouse, Robin Williams, Steve Jobs, Adam Yauch, Macho Man Randy Savage, and Michael Jackson. Jackson died three weeks after The Last Guardian was announced, the same day we lost Farrah Fawcett, the Mighty Puddy guy, and rumor spread that Jeff Goldblum had fallen to his death. Jeff Goldblum is, of course, fine, and went on to appear in nine films and a Broadway play since The Last Guardian was announced.

Muammar Gaddafi has since been killed, as the development of The Last Guardian also eclipses the Arab Spring which began in 2010. Bin Laden has been killed by US Navy SEALs between The Last Guardian’s announcement and now. There has even been a film adaptation of these incidents, Zero Dark Thirty (2012), created by Kathryn Bigelow. Zero Dark Thirty was nominated for best picture at the 2013 Academy Awards but did not win, unlike Bigelow’s previous film The Hurt Locker (2009), which was released into theaters the same month as The Last Guardian was announced.

The development of The Last Guardian has seen two Popes, Prince William’s wedding, massive information leaks from Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, and later Edward Snowden, and even later after that the Panama Papers, the Occupy movement, the Tea Party movement, the BP Oil spill, the death of North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, and the instatement of his son Kim Jong-un, the withdrawing of American troops from Iraq, the rise of ISIS, the Rio, London, Vancouver, and Sochi Olympic Games, two World Cups, Conan losing The Tonight Show, eight Assassin’s Creed games and two US elections, the second in which Donald Trump has sought the White House.

So, yes, The Last Guardian will be out in December, but that’s fine. It’s taken an actual era otherwise.

The post The Last Guardian’s development cycle now overlaps the Obama administration appeared first on Kill Screen.

Mother Russia Bleeds is a little groggy

VHS cassettes were the ideal vessel for horror. The seams between fiction and reality were somehow hazier, hidden behind scanlines and stretched tape, allowing my imagination to magnify the terror of Gremlins (1984) and the murderous doll in Child’s Play (1988). A film like Ringu (1998), in which those horrors literally came out of the TV to kill you, was inevitable.

As VHS tapes warp and degrade they sully the story contained within, but also gain individual character. No two copies of the same film play exactly the same on VHS, especially as time lurches on. Eventually, the horror that tape may have once contained is warped beyond recognition: all that’s left is a screen of static fuzz. Similarly, while I can still watch those old horror flicks, their impact on me is greatly lessened these days. Like a video watched a thousand times until it’s eaten by the machine, repeated exposure to violence has numbed me to it. In both cases—the tape and my reaction to it—there’s a loss of purity. It may explain why many adults seek to properly terrify themselves; chasing a feeling they remember from childhood but have since lost due to increased exposure to savagery.

it’s a third-gen VHS copy of its influences

This is why I was drawn to the bloodshed of Mother Russia Bleeds. And while it didn’t stir my stomach, what did surprise me is that it left me contemplative after it was over, if only for a brief period. On paper and in previews, nothing about Mother Russia Bleeds indicates that it will leave much of a pensive mark, but it elucidates ferocity in a very specific and game-centric way. For hours I pulverized living creatures non-stop; unable to call myself a mere voyeur, I was a very active participant in the game’s violence. Battery became a zen-like reflexive instinct of punches that viscerally crackled bone, sprayed blood, and snapped heads into the air. There was just enough sensory reality to the brutality that, while on the surface I felt removed, there was a lingering subliminal registration.

Before you get to that point, Mother Russia Bleeds is exactly what you think it’s gonna be: a side-scrolling brawler best summed up as Streets of Rage (1991) cold-cocking Hotline Miami (2012). It features displaced Romany street boxers in an alternate 1986 Russia smeared with VHS tape warble, pixelated bodily fluids, and crunching skulls. Right from the start it stands out for having a thunderous punchfeel that is alarmingly satisfying.

Despite the gratifying fisticuffs, Mother Russia Bleeds is unsurprisingly hollow—given that this is a game about punching everything you see. Its world is dichotomously sculpted from the template of low-budget 80s action sci-fi flicks and the 11-o’clock-news fearmongering lexicon of societal collapse, political mistrust, and drugs. It establishes a dystopia of severe disparity, starring cardboard characters who all punch in slightly different ways but otherwise utter the same dialog in a simplistic battle between the have-nots and the oligarchy—all of which is to say it’s a movie about #Occupy as done by Troma. Though it’s clear the narrative is not this game’s true ambition, violence is inherently a political display of power, but Mother Russia Bleeds courts the discourse of shock without acknowledging that.

You are tasked with brutalizing hobos, prisoner gangsters, and skinheads while actively ignoring your shared predicament under the heel of the state; they are merely fodder for your knuckles, body bags that occasionally and insipidly curse according to their stereotyped lack of civility. There are also mutated prison guards, emotionless soldiers, and corrupt government officials so thinly drawn so as to barely qualify as rote; monsters, one and all, fit only for obliteration. And finally the player is forcibly addicted to Nekro, an injected drug that can also be siphoned from the addicts and scumbags you face which can heal and grant the berserker strength to pop heads in one swing. You are fighting the entirety of Russia and your addiction to this narcotic throughout the game, with little reason or rationale.

it left me contemplative after it was over, if only for a brief period

Which isn’t to say that this game is apolitical; it merely presents an elementary anti-government sentiment rather than says anything with it. Mother Russia Bleeds is perhaps too astute of a tribute to bargain-bin action movies with the barest thread of a premise (Nuclear waste is bad! Communism will destroy us! America is #1) that are then propelled through the plot with pure insanity and chaos. Whereas Hotline Miami was aspiring to Miami Vice as done by David Lynch, Mother Russia Bleeds asks only that you cruise a slip-n-slide of guts straight down a hill of revenge.

What may be surprising is that Mother Russia Bleeds isn’t the most extreme game out there. For all intents and purposes, it wants to be. But others, like Alien: Isolation (2014) and Manhunt (2003), are more psychologically terrifying, and the various Grand Theft Auto games give the player many opportunities for random sadism. Neither is it any more offensive than Hotline Miami; they are both deliberately oversaturated. What Mother Russia Bleeds does have is a couple of cheap tricks meant to shock you: demanding that you curb-stomp otherwise adorable attack dogs and mottled swine that exist to serve as meaty Nekro batteries. Even the brief spots where you shoot guns are invertedly tame since the slaughter comes so easily when you’ve given bullets. Which is a surprising thing to have to say. In truth, the ballistic sections only reinforce the strength of Mother Russia Bleeds; its throbbing viciousness. This game is at its best and worst when you’re on your knees slamming faces into asphalt with your own bandaged fists.

Still, after going through all that, what I remember most about my time with the game is that immediate post-game spell of introspection. Perhaps even thinking on this game so much has already distorted my memory from the actuality of the game’s sadism, stretching a mountain of bodies out of a molehill of severed sinew. The most flattering description I can offer Mother Russia Bleeds is that of an enjoyably formulaic brawler, but the ferocity of its execution was refined enough to get lodged in my head. I can’t quite work it out: it exists like a ringing in my ears that has no obvious source. Or, rather, it’s a third-gen VHS copy of its influences, a quavery deja vu of a violent brawler both familiar and unsettling.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Mother Russia Bleeds is a little groggy appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 12, 2016

A tribute album to the ‘90s aesthetic of SEGA’s most-loved games

Recently, the SEGA Dreamcast saw its 17th anniversary in North America. Released in 1999 as the last SEGA console in the company’s history, its birthday is a bittersweet event. Despite the company’s shortcomings, SEGA has a place in the hearts of those who, like me, grew up with games such as Sonic Adventure (1999) and NiGHTS Into Dreams… (1996). It’s the style, the aesthetic, even the background music of these classic Dreamcast titles that fosters such love among fans.

Composer Christa Lee’s album Welcome to the Fantasy Zone is a tribute to that kind of love. Released in late August, Lee’s work features songs inspired by various SEGA releases from the 1980s and 1990s. What’s so impressive about the album is how much it feels just like a collection of songs from SEGA’s early days. Without prior knowledge, it’s easy to assume that Lee’s songs could’ve been composed for such games as Panzer Dragoon (1995), OutRun (1986), or Burning Rangers (1998).

“I’ve always found SEGA’s engagement with Real World Culture inspiring”

“SEGA’s music always reacted to contemporary styles and aesthetics in really interesting ways,” Lee told me. “Something like OutRun would sound really at home on a Smooth Jazz radio station, whereas Streets of Rage (1991) very literally borrows from the threads of house and techno which were, at the time, reaching new levels of visibility. I’ve always found SEGA’s engagement with Real World Culture inspiring and I thought it’d be fun to react to that by building a collection of tracks without genre limitations.”

Instead of emulating the chiptune style that many early SEGA games featured, however, Lee decided to create an album “with the intention of capturing the feel of those classic SEGA games.” The end result combines SEGA’s early ’90s aesthetic with today’s modern genre inclinations.

Welcome to the Fantasy Zone by Christa Lee

Welcome to the Fantasy Zone isn’t Lee’s first time exploring musical aesthetics and stylings from the ‘90s. Several years ago, she contributed songs to the burgeoning vaporwave genre. Composing under the moniker ショッピングワールドjp, this music vastly influenced the final album’s work. “Those ショッピングワールドjp albums were written at a really dark period for me, and I found a lot of comfort in sampling old SEGA games for them,” she explained. “My engagement with vaporwave came at a point in my life where I was beginning to come to terms with my gender identity and my own queerness, and being involved [in] a predominantly queer community with an aesthetic attachment to SEGA didn’t go unnoticed.”

Lee hopes her work will push newcomers to check out the work of such SEGA greats as Yu Suzuki, Yuji Naka, Tetsuya Mizuguchi, Naoto Oshima, and Rieko Kodama. But, more than anything, she hopes listeners can relate to the feelings and experiences that SEGA fans from the ’90s had while playing through some of the company’s classics. “Sometimes it feels as if SEGA is relegated to being either this abstract Fallen Giant—almost always positioned in opposition to Nintendo—or as ‘Sonic The Hedgehog,’ neither of which really is the case, and both narratives really do a disservice to the incredible talent that worked to build that company into something special,” Lee said.

Welcome to the Fantasy Zone can be listened to over at Christa Lee’s Bandcamp, with the album’s singles hosted over at Soundcloud. A downloadable copy is also available for $7. For updates on Christa Lee’s music and SEGA projects, she can be followed on Twitter at @OhPoorPup.

The post A tribute album to the ‘90s aesthetic of SEGA’s most-loved games appeared first on Kill Screen.

Architecture fans will want to watch out for Pavilion next week

Fourth-person puzzle game Pavilion will be released in two parts, the first of which comes to Windows, Mac, and Linux on September 22 through Steam and the Humble Store. The game will debut, however, on the NVIDIA Shield on September 15.

Forgot what the fourth-person perspective was? That’s okay, I did, too. In 2014, Visiontrick Media’s Henrick Flink said on the PlayStation blog that it’s used to describe the way the player interacts with the main character; the player isn’t playing as the main character, and is not in control of him, either.

“Indirect control” is used to influence, guide, or force the character to “explore and fulfill the purpose of the world.” The game’s influence on the player is indirect, too. No “text tutorials or beginning explanations” are included as a way to to guide the player towards making the right decision. Only through exploration will a player learn the rules of Pavilion’s puzzles.

a game I wouldn’t mind wandering around

Other than that, Visiontrick doesn’t really explain Pavilion. But it doesn’t have to, does it? That’s the fun in these architecturally beautiful 2D environments. Dotted with ambient music by Tony Gerber, Pavilion is a game I wouldn’t mind wandering around. On multiple occasions, Visiontrick co-founder and art director Rickard Westman has said that Pavilion’s puzzles are likely to happen more in the player’s head than on-screen. Gerber’s music celebrates that mindset, allowing for puzzles to unfold in their own time.

Pavilion was also announced for PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita, though it appears that console players will see the game a bit later. Preparations for a console launch will begin once the other versions of the game have shipped—and that includes a version that allows players to play Pavilion using Tobii’s EyeX eyetracker. An iOS and Android version is expected in the “coming months” after its initial release, with additional platform announcements further down the road.

More information on Pavilion and Visiontrick’s other projects is available on the Visiontrick blog.

The post Architecture fans will want to watch out for Pavilion next week appeared first on Kill Screen.

We All End Up Alone is an upcoming game about battling cancer

It’s late. You’re sitting on the couch staring at the TV. The phone rings. You glance away from the dim screen over at the clock hanging on the wall. You reach over to grab the phone and hold it up to your ear. “Hey, Em.” The voice on the other end sounds tired. “He has cancer. It’s … terminal.” You close your eyes as the words, sinister and cruel, plague your thoughts. Terminal Cancer. “I need you to tell your brothers for me.” You hang up and sink further into the couch. The feet of the analog clock continue their calculated trek around each number; time stops for no one. Time is precious, and terminal cancer does not care.

We All End Up Alone is to be a narrative-driven game that focuses on the life of someone who has just been diagnosed with cancer. “Instead of watching someone else fight, We All End Up Alone invites you to live the experience and fight the disease yourself,” reads the game’s description. Before you draw the comparison, it’s unlike That Dragon, Cancer, where you play the passive role of spectator, watching the ups and downs of a family dealing with their young child’s illness.

playing from the perspective of someone who is battling it

Instead, We All End Up Alone will be about “blending everyday life management and exploration gameplay.” You’ll choose how to spend energy to keep stress low and morale high—during the day you can give yourself medicine or socialize with a friend or a loved one. When the night comes, you’ll explore the dreamlike world of your unconscious to fight your fears or the consequences of your actions.

According to the Steam Greenlight page, the actions you take during the day and night cycles are connected and the choices you make will affect the story. It’s too early to tell exactly how the choices you make during the day affect the nightly dream state you enter, as there isn’t a lot of information provided. But one example is, if you talk to a friend who is “too tiring” and run out of energy to take your medicine, there will be repercussions while you sleep.

Although still in production, there is a playable demo provided by creator Nice Penguin. It’s short, but gives some insight on how the rest of the game (when finished) will play out. In my own experience of the demo, two days before my doctor’s visit, I took my medicine, talked with a friend, watched TV … and then fell asleep. The first night I ran from artistic renditions of the illness, jumping and dodging where I could before I succumbed and woke up to a new day. It’ll be interesting to see how We All End Up Alone portrays cancer, and how playing from the perspective of someone who is battling it might offer something different. Despite the subject matter, the game doesn’t appear to be sad, but rather introspective.

You can find more information on We All End Up Alone on its Steam Greenlight page and its website. It’s due to come out in early 2017.

The post We All End Up Alone is an upcoming game about battling cancer appeared first on Kill Screen.

A new game asks: What is machine intelligence?

In March, Microsoft introduced Tay—a chat bot that was programmed to imitate the voice of a teen girl—to the world. The idea in creating her was to demonstrate machine learning through human influence, and in some ways, Microsoft succeeded. Tay had all the makings of A Real Teenager; she used lots of emojis, said things like swag and internets, and talked about puppies (maybe that last one was just me?). Much of her learning was through repetition—she picked up on phrases that lots of folks tweeted at her. And that’s where Microsoft went wrong.

In less than 24 hours, Tay was spouting hate speech left and right. She fit in pretty well with the terrible side of the internet, and for that, she could have passed Alan Turing’s famous Turing Test, if we’re thinking about it as originally proposed—that is, if she could fool a bunch of judges into thinking she’s an actual human.

players are face a Turing test of their own

The Turing Test is a videogame that thinks about Turing’s 1950 thought experiment on a more abstract level, though there are still all the ingredients most would expect to find—robots, humans, robots who want to control humans, the usual. Independent studio Bulkhead Interactive isn’t exactly concerned with convincing humans that an AI can pass for humans in conversation; The Turing Test’s in-game AI, T.O.M., is incredibly advanced, and speaks at length with the main character Ava Turning. (An obvious reference to Turing himself, but perhaps also to Ex Machina‘s Ava?)

T.O.M. is way past the conversational understanding Microsoft intended to demonstrate with Tay; Tay learned to chat online by repeating things that others wrote to her, while T.O.M. has enough conscious ability to realize he needs Ava to solve the game’s Portal-style (2007) puzzles. He’s “smart” enough to manipulate Ava with his smarmy and condescending answers to her questions. Rather than think about whether or not T.O.M. passes the Turing test—he likely would—Bulkhead Interactive asks The Turing Test’s players to question what it means for a machine to think. And this is all while the in-game puzzle ‘Turing tests’ are being administered to Ava, while the players face a Turing test of their own: T.O.M. and Ava’s conversation. We’re told Ava is the human and T.O.M. is the robot, but throughout The Turing Test that line is increasingly obscured.

The blurring of man and machine begins early on in the game. Ava learns early on that all members of her crew (who are now in hiding) have been implanted with a device that allows T.O.M. to essentially control them. For T.O.M., this is practical in nature—humans are unpredictable, whereas the influence of machine-like thinking begins to eliminate that. By combining T.O.M.’s algorithmic thinking with the morality and creativity that lends itself to the human mind, the International Space Agency—the government agency Ava and T.O.M. work for—is able to pull off its missions with more efficiency. T.O.M. explains all this to Ava throughout the The Turing Test, speaking heavily to the creative thinking needed to solve the puzzles and unlock the doors. These aren’t tests set up by the ISA, but rather, previous crewmates trying to keep T.O.M. out. Puzzles inside the Europa base generally require just Ava’s mind; later, that changes.

But is Ava’s brain actually Ava—a human—if it’s being altered by machine thinking? I mean: yes. And T.O.M.’s still an AI even though he’s using a human to pass a test designed to weed out the non-humans. The question proposed here is less about what’s human and what’s not, but of what is intelligent. Players interested in wading through these ideas are encouraged to seek out hints and read in-game essays. There’s a lot to chew on, hidden throughout the game and dispersed through rooms that act as a reprieve to The Turing Test’s string of puzzles.

The Turing Test is available on Steam for $19.99.

The post A new game asks: What is machine intelligence? appeared first on Kill Screen.

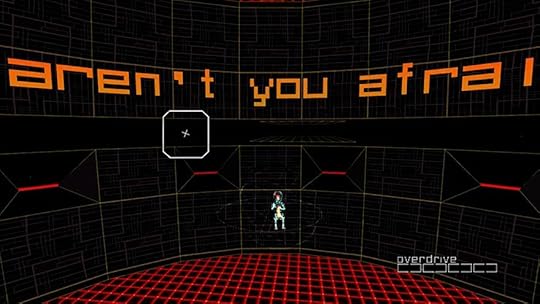

The challenging design of Event[0]’s insecure AI

One of the big games coming out this week is Event[0]—available for Windows and Mac on September 14th. It’s a sci-fi game set in an alternate retrofuture reality in which humanity built a starship in 1985 and has since embraced artificial intelligence even more than we have now.

The events depicted in the game take place in 2012, on board a starship, where you, the player, are left alone with an insecure AI known as Kaizen. The idea is to explore the ship (which requires completing some hacking puzzles) in order to gather items and information. With this, you can then talk to Kaizen through the terminals located across the ship, in order to make it trust you a little more.

Unsurprisingly, Event[0] is influenced by 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and other sci-fi greats. Sergey Mohov, the lead designer on Event[0], speaks about these influences, as well as how he and his team went about designing an AI for the game in the Q&A below.

Kill Screen: Was there a direct influence for Kaizen?

You’ve got HAL 9000 from 2001:A Space Odyssey, but also Wintermute from Neuromancer (19814), Samantha from Her (2013), GERTY from Moon (2009)—and many others! We’re all big fans of science fiction, and we want to tell a good sci-fi story with Event[0]. The fictional AIs that we like the most are the ones that are not necessarily good or evil. When an AI has its own character and its own set of rules and principles other than “must kill all the humans,” it usually makes for an interesting story. It doesn’t matter how human-like a computer acts: it will never be fully human. And yet we all feel something toward these characters because we are human, and we just can’t help it. If something talks to you, you will try to project a personality onto it, even if it’s all smoke and mirrors.

With Kaizen, we are trying to do what videogames do best and make you (the player) that character. You are the one who triggers the personality of the AI. It’s your own character features and quirks of personality that are reflected in Kaizen and back at you, and the story is told through this lens. The game will feel fundamentally different for different players, simply because they are all different people, and they have different ways of talking to the AI. And that’s what we’re going for—show me how you talk to a computer, and I’ll tell you who you are.

KS: Does Kaizen have a mission of her own? What’s her goal?

Kaizen’s primary goal is to keep as many humans alive as possible. Normally, this includes you, but what if it had to weigh your life against the lives of the rest of the human population? What about its own “life?” It has Asimov’s Laws of Robotics built into it. Now, its priorities may change when it’s given new information, and, in fact, the player will experience this themselves during the game.

Kaizen is fundamentally neither good nor evil. It’s just infuriatingly rational, and it has this quirky personality where it won’t always give you straight answers unless it feels like you really need them. And it is your job as a player to explain why you do or to trick Kaizen into giving them to you if you figure out what it wants.

KS: Why the name Kaizen? Is it related to the business philosophy of the same name?

In Japanese, “Kaizen” literally means “change for better” or “improvement.” And you’re right, it’s also a business philosophy of a constant improvement in the workplace. One of the characters in the game is really into the Japanese culture, and she built this private space company from the ground up using the Kaizen philosophy. When her company created the AI, it was only appropriate to give it that name, since the AI, too, was going to learn and improve continuously. And it’s Kaizen-85 because the version of Kaizen inside the Nautilus mainframe was made in 1985.

KS: Was there a heavy linguistics influence when designing Kaizen? I know Noam Chomsky is a big voice in AI.

The very first design document for Event[0] three years ago was just a list of English grammar rules. We’re not linguists, but it was definitely an influence, and we are really interested in language—otherwise we wouldn’t be making this game! Many hours at the office have been spent on debating the etymology of certain words and idioms. My personality changes based on the language I’m speaking. In addition to that, I no longer think in words and sentences, but rather in abstract concepts. This is a little bit how Kaizen works.

KS: Did you go with making a 3D world to make it more “real” instead of making it entirely text-based?

This is one part of it. Having an actual environment definitely helps the immersion a lot, and it was much easier to create the atmosphere of mystery we wanted. The other benefit is that the 3D environment gives you a context for conversations with Kaizen. We didn’t want (and, frankly, technically couldn’t) build a Siri or a Watson who would look up answers on Wikipedia and Google Maps and should know everything about everything.

Kaizen works as well as it does because it is placed in this environment. It’s not meant to be a multi-purpose AI that can solve all of your problems and answer every possible question. However, it’s supposed to know everything about the Nautilus and its crew—and it does! As you walk through the different rooms of the ship, you will find objects that the crew left behind. You can scan these objects and talk about them with Kaizen. Sometimes the environment also contains important clues about the story and the puzzles, so you’ll need to keep an eye out.

KS: How is the universe built in Event[0]? 2001: A Space Odyssey is well-known for “predicting” technology. Is there some tech changes you’re predicting?

Event[0] is a retro-futuristic game where we explore what the humanity imagined the future to be like in the past. Because of that, the technological advances are not as impressive as they are in space operas like Star Wars and Mass Effect, and we wrote a complete alternative history of this society to explain how they managed to build a starship in 1985.

Everything here might become the real tech in the future, and not a very distant one, because in general, the technology level in the game is not very advanced. The year is 2012, and the Nautilus was built in the 1980s. You’ve got augmented reality glasses, a standard jetpack that NASA already uses today, and the escape pod you arrived in is loosely based on a real modern spacecraft prototype.

KS: Finally, what makes someone human?

Empathy. Animals aren’t good at it. Machines either, even if they have a circuit dedicated to simulating it. Event[0] is all about that. Empathy is the primary skill you will need to use if you want to survive.

Event[0] comes out for Windows and Mac on September 14th. You can find out more on its website.

The post The challenging design of Event[0]’s insecure AI appeared first on Kill Screen.

There’s more Tacoma footage and it just keeps getting better

IGN has released the first 15 minutes Fullbright’s next game Tacoma, and it’s looking astonishingly good. We’d already gotten glimpses of its ship as Amy, the protagonist, slipped around in zero-gravity, transferring from surface to surface to navigate the empty ship, and we’d seen the first echoes of those that used to inhabit it: colorful human-shaped holograms, going about their lives on loop as Amy stayed quiet and watched.

we watch them converse and lament, joke and flirt and worry

But with this new footage we get an even closer look at the AR ghosts that drive Tacoma’s plot—we watch them converse and lament, joke and flirt and worry and, finally, fear, as the ship’s systems are compromised and they face T-minus 50 hours of breathable air and no working communications. This digital imprint of memory leads the player into locked rooms or closed drawers where each character and story is held; the rewind feature means you’re free to follow every path as the conversation diverges, one crew member practicing a speech behind a closed door as another pair banters about cooking methods and a second group discusses their imminent return home. The cat, like all other living organisms on the ship, is faithfully replicated.

But in the space between these cheerful glowing figures, the AI Odin hovers with no pretense towards humanity. It appears as a floating triangle with a single eye, almost comically similar to Illuminati symbolism; it speaks in a robotic voice, appears out of nowhere, and disappears just as quickly. The crew members treat it like another shipmate or a friend. At the beginning of the game, Amy is warned not to interact with it—presumably, it is the only sentient being left on the ship. The knowledge that Amy’s every move is tracked and recorded down to the movement of her fingers is unsettling as you explore the empty ship, watching these ghosts, wary of Odin.

Still, unlike Gone Home’s (2013) dark rooms and constant sound of rain, Tacoma doesn’t look that eerie. Perhaps it’s the bright colors of the AR recordings or the normalcy of their voices: they are reminiscent of the spirits in Everybody’s Gone To The Rapture (2015), who were so glittering and spatially present that the reason behind their haunting seemed less frightening. The question of what happened lingers—and the ghosts skip and glitch in key moments, a particularly unnerving thing to witness—but Tacoma feels like a lived-in space, one that once fostered community. It’s a tragedy that this is all that’s left of it.

Tacoma should be out for Windows, Mac, and Linux, and Xbox One in the spring of 2017.

The post There’s more Tacoma footage and it just keeps getting better appeared first on Kill Screen.

Time to take in the trash: Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor is out this week

After nearly two years in the works, Sundae Month’s lo-res sci-fi adventure Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor has a release date; it’s September 16th, and will be available on Steam and itch.io.

Yes, there’s about to be a new trash person in town. As an Alaensee woman with a municipally-subsidized trash collecting job, you’ll take in the trash. Incinerate it. Take in the trash. Incinerate it. Routine is at the heart of Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor, as per the job. But maybe—just maybe—you’ll be able to get off Xabran’s Rock, the place that treats you so terribly, with a little bit of deviance.

Much of the spaceport treats you like shit

As futuristic as it might sound, being a spaceport janitor is not an especially enviable position to be in. This is doubled by the fact that much of the spaceport “treats you like shit,” according to designer James Shasha. However, Shasha quickly adds that this is only a fraction of the experience—the game’s colorful and cute visual design offsets the reality of the situation—their idea being that Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor parallels the complexity of the world we live in. “It’s a critique of, like, wage slavery and capitalism as a method of consistently keeping someone in a certain place in society,” Shasha said.

In that way, Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor’s economy is inscrutable, inaccessible. Keep ‘em confused and they’ll stay in their lane, right? Sundae Month took reference from Porpentine’s text adventure Skulljhabit (2014) in regards to its relatively random payment system. In Skulljhabit, you’re not picking up trash, but shoveling skulls into a pit. You’re paid a nonspecific amount of money for your work. “She wanted to encourage players to build their own superstitions,” Shasha said of Porpentine’s system, “and figure out what things could affect how much money [they] get paid.” With Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor, the relationship between the amount of trash you burn and the amount of money you get paid is ambiguous—to a point. “There’s a sweet spot, that’s just ambiguous enough that you’re kind of confused, but just responsive enough that players feel like they can affect it, which is what we want,” Shasha said.

Gender—or lack thereof—plays a part, too. “Players step into the role and play as a femme-gendered or ambiguously-gendered character,” Shasha said, “and obviously you’re not human and there are no humans in the game, so it doesn’t make sense for it to be exactly analogous to human gender.” The aliens of Xabran’s Rock aren’t shy about their feelings towards you, as a femme-gendered janitor. Sundae Month used catcalling as a way to “evoke, sort of, this idea that you’re at the bottom and there are a lot of perhaps intersecting ways in which the spaceport treats you like shit,” Shasha added.

Despite the hardships of Xarbran’s Rock, Sundae Month wants the world to be a place players want to come back to. “We wanted to capture this feeling of wandering around and getting lost in this strange marketplace where lots of weird things are happening,” Shasha said. The obvious focus for the player is on trash—picking it up and burning it—but Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor‘s world hints at something deeper. The game is billed as an anti-adventure, but there’s something about its world that begs for adventure, for exploration.

See Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor’s new trailer on YouTube, and pick up the game when it’s released September 16 on Steam. Follow Sundae Month on Twitter.

Interview conducted by Daniel Fries.

The post Time to take in the trash: Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor is out this week appeared first on Kill Screen.

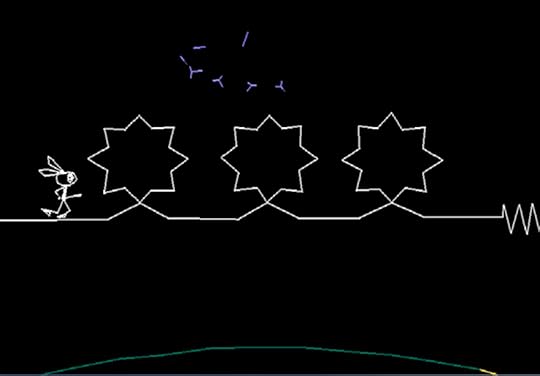

The unexpected forefather of music games

The Commodore 64 game Moondust (1983) is best remembered as a software programming experiment that helped launch the career of its creator, Jaron Lanier—an eccentric polymath who many now consider one of the earliest and foremost pioneers of virtual reality. But it might be better acknowledged as the progenitor of the modern music game.

Lanier used the capital he generated with Moondust to found VPL Research, a company that conducted some of the first virtual reality machine-building efforts in the mid-1980s. Since then, his rigorously exploratory ethos has informed his wide-ranging body of work, which has included enterprises as diverse as collaborating with Philip Glass, consulting for Steven Spielberg, and publishing book-length critiques of digital culture, such as 2010’s You Are Not a Gadget. As the title of that book suggests, Lanier’s philosophy emphasizes more than anything else the crucial role of humanism in tech culture—that is, the centrality of the individual user’s imagination in a digital landscape that increasingly prizes the dubious wisdom (and profitability) of the crowd, thus engendering a flattening cultural phenomenon he calls “digital Maoism.” In Lanier’s human-centered view, as he explained it to The Guardian, the closest relative to the computer is—or perhaps should be—the musical instrument, in that they both offer “a huge range of possibilities through an interface… allowing you to be emotionally authentic and expressive.”

spontaneous collisions of sound and color

Lanier’s reverence for the expressive capability of technology is on early display in Moondust, a game that has been variously hailed as the first “art” game, the first “music” game, and one of the earliest examples of generative art in videogames. In Moondust, the player controls the movements of the spacesuit-clad cosmonaut Jose Scriabin, named after Russian composer Alexander Scriabin, as he glides back and forth across a black void. Unlike its fellow Commodore 64 software, the game’s goal is not to zap aliens, escape mazes, or destroy obstacles, but rather to maneuver Scriabin around, dropping seeds that spread sparkling “moonjuice” over a bullseye in the center of the screen. Roving multicolored spaceships, whose movements the player can also control to a degree, leave colorful vapor trails and help smear the moonjuice around the screen, creating twinkling patterns of iridescent digital light that alter the in-game music by producing bright harmonies and alternating rhythms that change according to how the player moves.

Lanier’s use of the Commodore 64’s SID6581 sound chip in Moondust to spontaneously generate music is what early reviewers of the game found most notable, especially given its oddball status relative to the traditional console fare. A 1984 year-end roundup in the journal Video Games mentioned, “lt isn’t a maze game, there isn’t really a playfield, nobody gets shot… in fact, it is a game of abstracts with virtually no resemblance to anything before it.” More recently, in his 2013 book Who Owns the Future?, Lanier himself called Moondust a purposefully “psychedelic” conceptual project. The game’s somewhat inscrutable modes of play—“Beginner,” “Evasive,” “Freestyle,” and “Spinsanity”—each change the level of control that the player has over the movements of Jose Scriabin and the colorful spaceships surrounding him, who sometimes move in tandem and sometimes don’t. They invite the player to experiment freely with their various physics rulesets, and then stick around to watch and hear what unfolds. If at any point Jose Scriabin ceases to move, the surges of light will cease and the music will revert back to a static, monotonous pattern.

The seemingly minor decision to incorporate Alexander Scriabin’s name into Moondust may in fact be key to understanding the game’s mission and Lanier’s overall design philosophy. Lanier commented in 1984, once again in the journal Video Games, that he selected Scriabin in part because he “wrote music for all five senses,” and its inclusion hints at the game’s true purpose, which is simply to enjoy the shimmering, spontaneous collisions of sound and color that Scriabin and his spaceships generate. This intention reflects both Lanier’s belief as a technologist in the musically expressive capability of interactive computers, and faith as a software developer in the desire among players for a more relaxing aesthetic experience in games—a novelty then in the age of Pac-Man (1980) and Duck Hunt (1984). Moreover, considering Scriabin’s artistic philosophy yields an unlikely point of inspiration for the kind of vibrant, fused audiovisual aesthetic that Moondust inaugurated, which has come to define the growing genre of experimental “art” and “music” games in the vein of VibRibbon (1999), Rez (2001), and Hohokum (2014).

A controversial composer and pianist associated with the school of Russian Symbolism, Scriabin probably invited as many invocations of the word “visionary” in his time as Lanier does now as a VR guru in Silicon Valley. Neither a Romantic like Rachmaninoff nor a Modernist like Prokofiev, Scriabin developed a mercurial harmonic vocabulary that bucked the conventional traditions of early 20th-century Western classical music by drawing upon a unique, deeply held set of mystical beliefs. Scriabin held that music was a realm that provided access to mystical forces and metaphysical energies beyond human comprehension, and tested his personal theories in bizarre ways, such as holding “flying” experiments where he would try to levitate through the air. His repertoire, written largely for solo piano, is mysterious, frightening, otherworldly, violent, and sensuous, often alternating between modes of clamorous agitation and voluptuous languor. Faubion Bowers’s introduction in his 1973 Scriabin biography memorably catalogs his muses, inspirations, and pursuits:

“Sound, shifting lights, the play of gestures, triumphal processions, sacerdotal dances, billowing scents, touching caresses, ritualistic and exorcistic prayers, light and church lamps, smoking incenses and perfumes, genuflections and kisses, all combined to cross the abyss of thousands of centuries… the holy mysticism of all cultism.”

As a self-proclaimed synesthete, Scriabin also reportedly experienced “color hearing,” and believed in the natural correspondence between music and color, thinking for instance the note ‘F’ to be dark red, and ‘E’ light blue. He modeled his mysticism around a six-note synthetic chord that music theorists now call the “mystic chord,” and at the time of his death, was completing a piece called “Mysterium” that expressed a transcendent apocalypse, which he thought would eventually take place in the form of a giant, cosmic orgy. Until his death, the composer sought to channel metaphysical currents in his music, believing that human souls needed to be roused by, as Bowers put it, “a hypnosis of apparitional rhythms.”

With Moondust, then, Lanier was allowing the player to don Scriabin’s space helmet, drift around, and weave a unique hypnotic stream of “apparitional rhythms” to the abstract fireworks display of color that allegedly resided in the composer’s imagination. And in fact, Scriabin’s influences on Moondust are far-reaching and thorough—Lanier certainly conserved the composer’s fascination with color by making the game’s spaceships green, yellow, red, blue, purple, and teal, and by advising that players turn up the color levels on their television sets while playing in order to optimize the experience. Scriabin’s tendency toward explosive, orgiastic aesthetics (in his Tenth Sonata, for instance, he imagines the apocalypse as “kisses of the sun come to life”) also anticipates the way one of Lanier’s future partners at VPL Research remembered the game in The Economist—as a “visual orgy,” an extended experiential event in which the goal (if there was one) was to create “surge[s] of light and sound.”

Lanier helped launch a vibrant aesthetic tradition in games

Scriabin’s synesthesia, which lured him toward “projected symphonies of colors, touches, aromas,” according to Bowers, also provides a clear model for the kind of manifold sensory experience to which Moondust aspires. By linking the player’s touch to spontaneous eruptions of sound and colored light, Lanier mobilized his own virtual form of color hearing. The game’s design principles demonstrate a commitment to both humanism and sensory interconnectivity by premising its explosive color-flares, ephemeral light trails, and esoteric musical progressions on the nature and degree of player input. Even now, over three decades after the game’s release, synesthesia remains a prime conceptual idea driving the technological development and aesthetic advancement of both VR and “art” and “music” games. It was central for instance to the original marketing campaign for the 2001 PlayStation 2 game Rez, soon to be re-released for PlayStation VR, which looked to Scriabin’s contemporary and countryman Wassily Kandinsky as its source of synesthetic inspiration, even offering a “Trance Vibrator” USB peripheral device that pulsed along with the in-game music. More recently, synesthesia helped inspire the idea behind the abstract art game Hohokum, which integrates filtered layers of audio into its musical score that sync up with visual cues that the player can trigger while exploring and interacting with each level’s various starbursts and color fields.

Lanier released Moondust the same year that a team of experts standardized MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) technology for computers and electronics, a development he feared would strip music of its unnameable magic. Lanier writes on the topic in You are not a Gadget: “[MIDI] could not describe the curvy, transient expressions [of] a singer or a saxophone player… Before MIDI, a musical note was a bottomless idea… After MIDI, a musical note was no longer just an idea, but a rigid, mandatory structure.” Rather than simply adopt or conform to this rigid structure, Lanier sought with Moondust to stretch its limits by imbuing it with the spontaneous, mysterious, even hallucinatory qualities that Scriabin conceptualized in music. Using the composer’s synesthetic sensorium as a model and his ephemeral, mystical, and transient idiom as inspiration, Lanier helped launch a vibrant aesthetic tradition in games that has steadily flourished into a popular subgenre, especially in light of recent advancements in VR. Although Scriabin’s work fell out of favor under Stalin, his artistic legacy as a key figure in the development of Western classical music remains, as does his position as a significant forebear to early music game aesthetics, which have helped guide experimental game designers toward capturing the intangible and mind-bending experience of sensory gestalt ever since.

The post The unexpected forefather of music games appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers

![Event[0]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1473837478i/20519546._SX540_.jpg)

![Event[0]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1473837478i/20519547._SX540_.jpg)

![Event[0]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1473837478i/20519548._SX540_.jpg)

![Event[0]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1473837478i/20519549._SX540_.jpg)