Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 62

September 3, 2016

Weekend Reading: I Am The Passenger

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Perpetual Motion Machines, Chenoe Hart, Real Life

As self-driving cars dawn over the horizon of the highway, it’s clear that the world might be transformed in ways that are still difficult to process. Chenoe Hart provides a wonderful essay about the place where everyone’s a passenger.

Amy Schumer’s New Obligations, Jia Tolentino, The New Yorker

A controversy has recently surrounded Kurt Metzger, a comedian whose toxic behavior and general attitudes seem to directly contradict the feminist messages of the show he’s famously writing for, Inside Amy Schumer. Jia Tolentino (one of Kill Screen’s favorite essay writers, for the record), goes over the tricky dilemma of Schumer, a comedian who is very efficient at being a feminist comedian, but less so in other platforms.

Aya Suzuki: In Her Own Words, Andrew Osmond, All the Anime

Aya Suzuki has worked on films with contemporary animation masters like Hayao Miyazaki, Sylvain Chomet, and Masaaki Yuasa. In a candid discussion during an anime convention, transcribed by Andrew Osmond, Suzuki discusses the culture of animation across distances and personalities.

Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop: compulsion and comedy in Serial Mom, Jovana Jankovic, cléo

A middle child for John Waters, Serial Mom has been mostly overlooked for it’s sheer camp and lack of Waters’ usually more aggressive provocations. Jovana Jankovic gives the film its share fake, celebrating it beyond just a b-movie riff.

///

Header image, from Desert Reality by Ed Freeman.

The post Weekend Reading: I Am The Passenger appeared first on Kill Screen.

September 2, 2016

Turns out that 11 to 14-year-old girls can make the cutest games

Let’s be frank: it’s not easy working as a woman in games. The past few years have been particularly tough for us. But as women in games, each of us feels a responsibility to help and support each other while working in this space. Especially when it comes to helping young women enter the field. Whether as designers or artists, programmers or journalists, we want to put our experience to use and give aspiring women the tools they need to pursue their interest in videogames.

Girls Make Games is one initiative that fulfills that goal. Hosted by LearnDistrict, Girls Make Games is “a series of international summer camps, workshops and game jams designed to inspire the next generation of designers, creators, and engineers.” The organization draws young girls (typically aged between 11 and 14 yearsold) together across the United States, with the goal of teaching them how to create their own videogames from scratch. Topics of discussion include everything from programming to audio engineering to game design. And at the end of the summer, Girls Make Games hosts an annual Demo Day, in which the five best national development teams compete for the chance to turn their prototypes into a full-fledged videogame via Kickstarter.

the team was praised by the program’s judges

BlubBlub: Quest of the Blob is one such game. Self-described as a classic platformer, the game revolves around BlubBlub, the most adorable blub in the entire world. When a mad scientist named Jennifer captures BlubBlub in an attempt to build a cosmetic empire from extracting its cuteness, BlubBlub escapes—and tasks itself with saving its best friend Blobby from her evil clutches. The action is straightforward enough, as BlubBlub must jump, drop, and dodge obstacles in order to make it out alive of Jennifer’s lair.

BlubBlub’s Kickstarter is based on a prototype demo made in Stencyl, which was later pitched during 2016’s Demo Day event. Created by a group of four girls from Girls Make Games’s Boston camp, the team was praised by the program’s judges for BlubBlub’s passionate development and challenging play. Just take a look at the demo to see what they mean—the first level alone is quite a challenge.

Planned for a March 2017 release, LearnDistrict’s Kickstarter looks to raise funds for professional programming, artwork, and music for release. Stretch goals include mobile ports, PlayStation support, a level editor, and an open-source release of the game’s code.

If you’d like to support the Kickstarter for BlubBlub: Quest of the Blob, feel free to check out the official page for more information.

The post Turns out that 11 to 14-year-old girls can make the cutest games appeared first on Kill Screen.

New boardgame is like Dungeons & Dragons without all the violence

Lotus Dimension, a tabletop game by Scott Wayne Indiana that’s currently on Kickstarter, riffs on the best-known parts of Dungeons & Dragons (1974)—lots of adventure, deep storytelling, and actively encouraging creativity—but removes another: combat. Gone is the hack’n’slash, the destructive sorcery, the sharp but hidden blades that sawed your way through oh-so-many dungeons; you’re going to have to be more clever now. Lotus Dimension has sworn a vow of nonviolence, and you have no choice whether to follow it. Now pacifism has outgrown its adolescence of achievement runs and takes a seat with its grandfather at the tabletop, it’s time to learn the virtues of patience in a world that doesn’t allow saving and reloading.

”replaces violence and weaponry with empathy and ingenuity”

“If you can’t kill it, get creative” is the first thing any novice D&D player would learn during their maiden venture into its world. Lotus Dimension is simply removing step one. If you know you can’t kill it from the beginning, what else can you do? In Lotus Dimension, that question underlies the whole game. As the Kickstarter states, it “[replaces] violence and weaponry with empathy and ingenuity.” You’re forced to work around combat, and in an adventure game like this, that mentality can completely change the way you play the game.

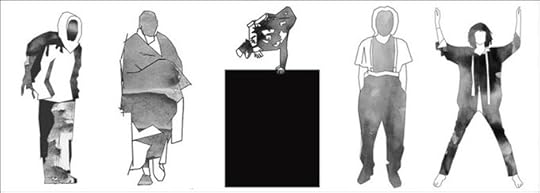

Like D&D, Lotus Dimension has character classes with different strengths and weaknesses, but their similarities end there. In Lotus Dimension you could be a hacker, or a mystic, or even a free-runner (because we’ve all wanted to try parkour, haven’t we?). These classes and others follow a leveling/stats system “loosely designed around the noble eightfold path in Buddhism,” again reiterating the game’s focus on nonviolence. In fact, Lotus Dimension was inspired by pacifist philosophies, as well as historical figures like Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. who became famous for advocating nonviolence.

Lotus Dimension believes that the possibilities of pacifism are just as fruitful as those that are quicker and violent, and wants to make the extent of these possibilities known. The tabletop RPG was born in a dungeon surrounded by men with swords, but now the genre has grown up. Hopefully the rest of us will be able to too.

You can support Lotus Dimension on Kickstarter here .

The post New boardgame is like Dungeons & Dragons without all the violence appeared first on Kill Screen.

From the magazine: Red Dead Redemption, Reviewed

This article first appeared in Kill Screen’s relaunched magazine, Issue 9, which you can buy right now! Even better, through Labor Day weekend use the discount code “LABORDAY” to get 10% off a subscription and a free digital mega-bundle of all our back issues of the magazine.

Header illustration by Christopher Black

///

In 2003, HBO released And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself, a lavish TV movie about a Mexican revolutionary who makes a deal with Hollywood to film, and star in, his own battle. Antonio Banderas plays Pancho Villa full of preening swagger, yet a strange kind of naivete—the naivete of someone already trying on the gilded robes of myth, already saving a parking spot on Olympus, boasting like Beowulf before the fact. The battle does not go as he intended; what was supposed to be a decisive skirmish becomes a prolonged siege. But the camera is there to watch him as he smiles for it between gunshots—as he carries around an idea of the present moment, an idea of what the past will look like to an appreciative future, without much care for the present itself. The camera is there to watch him as he executes the widow of one of his enemies, point-blank, in cold blood.

The historical Pancho Villa was almost certainly one of the inspirations for Abraham Reyes, a revolutionary encountered by John Marston midway through Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption, from 2010. Like Villa, Reyes is a terribly human character who basks in the light of his own potential mythology. He boasts constantly of the corridos—heroic ballads—that will be written of his battles, his exploits, eliding the fact that Marston was the one who killed hundreds of Federales with a pistol from behind a dingy barrel. The game makes it crystal-clear that Reyes is exactly like the Generalissimo he seeks to depose: selfish, autocratic, stupid, corrupt.

“I am not afraid to die.”

In a running gag that runs one too many times, Reyes forgets the name of Luisa, the woman who saves him and adores him. But we know by that point that she has a more realistic relationship to history than he does, even though she has done more to affect its course—a sense of its oppressive weight, its unharnessable vastness. “When I rule these people, I shall be fair and judicious and wise,” says Reyes, writing the Book of Reyes a priori, letting the verb “rule” (and his name) tell us already what kind of ruler he will be.

“I am living in history,” Luisa says, in stark contrast. “I am not afraid to die.”

///

Far Cry Primal, Ubisoft’s recent open-world caveman simulator, begins, technically, in the present. The year 2016 appears onscreen, bordered by a white rectangle, and we hear the whine of passing cars, a cacophony of languages speaking with postindustrial impatience—the sounds of our age. A second later, the number starts ticking down, and the sounds change with it: machinegun bullets zoom through the 20th century; train whistles blow throughout the 19th; Gregorian chants, snippets of Italian, the neighing of horses, the clanging of swords linger on. As the years count down, the sounds thin out, giving way to pools of silence. Only an earthy rumble heralds the coming of the game’s own era—10,000 BCE, before history began.

This 30-second opening might be better than the entire game that follows, if only for the way it works (perhaps inadvertently) as an encapsulation of the genre as a whole. By whisking us back from the high-treble nattering of the present to the deep groaning of the prehistoric past, Primal tries to make the case that it’s about something more fundamental (i.e. primal) than other videogames, many of which traffic in the sounds of bullets or slashes or hooves.

But that pivot from history to prehistory also ends up underscoring something else: that there’s been an open-world game—similar in structure, ethos, and overall design philosophy—for almost every other period you can hear in that sonic tapestry, necessitating a game both prehistoric in setting and post-historical in nature. Assassin’s Creed alone has entries that cover the Crusades, the Renaissance, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, Victorian England, and the Americas more broadly throughout the 18th century. Grand Theft Auto covers ‘80s Miami, ‘90s Los Angeles, and 2000s New York. The Saboteur (2009) covers Nazi-occupied France during World War II. LA Noire (2011) covers Los Angeles in the 1940s. Red Dead Redemption covers the American West in 1910, on the verge of becoming something else. Only antiquity—and the entire history of East Asia, minus contemporary Hong Kong—remains unvisited by roaming, ethically ambiguous avatars in search of historically accurate prostitutes. We shall see what the next Assassin’s Creed will bring.

Every one of these games has attempted to recreate a different setting in loving, studious detail, with years of development spent copying architecture, combing through archives, and consulting with academics. Of course, the way Primal’s opening alludes to each era through exemplary snippets of noise—these crystallized fragments of atmosphere—is analogous to the way these games tend to present history through events, people, and places that have ossified into caricature. Like Mel Brooks’s History of the World Part 1 (1981) and Epcot’s Spaceship Earth, the sequence is a ride through History’s Greatest Hits. So, too, is the genre as a whole. And to be sure, almost none of these games aspire to be history texts, per se; they’re all speculative, fictional, sometimes even counterfactual (see, for instance, the sublimely ridiculous Assassin’s Creed III spin-off The Tyranny of King Washington from 2013). In many ways, you could argue that they use history as little more than a playground and a backdrop. But they’re also a lot bigger, a lot more ambitious, than we tend to give them credit for. Taken together, they compose a cohort of historical epics unparalleled in size, expenditure, and potential ideological impact since the golden age of Hollywood. It would be foolish not to take them with a grain of salt. But it would be equally foolish not to take them seriously—not to ask what kind of history they tell.

///

Many (perhaps even most) videogames are ahistorical, not only in their subject matter, but in the experience they offer. Many would seem to align implicitly with Nietzsche’s assertion—in his seminal 1874 essay “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life”—that true happiness is achieved by forgetting, by putting down the weight of the past. There is no time in Super Mario Bros. (1985)—only the time you have to complete the level. There is no time in Zelda, either, despite the Temple of Time; it’s a space of myth, frequently trafficking in images of suspended animation. For most of the history of the medium, history itself has been the near-exclusive province of strategy games like Age of Empires and Civilization, which represent (or remix) world events according to a model of historical change that stresses macroeconomic factors. Play Civ V (2010) long enough and it becomes hard not to see the story of the world as a story of strategic resources.

Open-world games with historical narratives are very different, both from games that try to take us out of history, and from games that try to abstract it. They still aim for escapism, but they also aim for some measure of educational value, some explanation that the player can take back to the world outside. And the way they explain history, in turn, is truly and weirdly hybrid.

On the one hand, despite the ostensible openness of their worlds, these games have linear plots that emphasize the agency of individual figures, chief among them the player. True, they never seem to put you in the position of a king or a president or a general; instead, Assassin’s Creed games (and Red Dead also) have protagonists that are like Zelig or Forrest Gump, appearing almost accidentally at crucial turning points, determining what happens in indirect, invisible ways. But you’re still unmistakably an agent of historical change, and these stories—especially Assassin’s Creed’s plots, with their focus on the elimination of significant individuals—inevitably massage history itself into a saga of Great Men and Great Deeds. One of the first historical novels in English, Walter Scott’s 1814 work Waverley, was about a disaffected, bumbling young aristocrat who—by virtue of being in the right place at the right time, or the wrong place at the wrong time—ends up affecting the course of the Jacobite rebellion. Open-world games follow a similar mold. But they’re also allergic to the idea of incompetence. There is perhaps no better Gamer Power Fantasy than the enfranchisement of the invisible badass, turning the wheels of history and being recognized not by historians, but by other Great Men.

There is one big, beautifully coherent exception

On the other hand, at the very same time that they present what Nietzsche calls a “monumental” history of powerful individuals and willful action (however covert), these games present something like a materialist history of the mundane, conjuring the essence of an era through an authentic simulation of its objects. They strive for texture and immersion; they break gameplay into accidental anecdotes, as well as one propulsive saga. You save the world and chill with Napoleon, but in between missions, you wander the streets, visit shops, collect objects, and interact with a sprawling population of ordinary digital citizens. The nature of the period becomes manifest in the sound of a butcher hocking his wares, in the shadows cast by gas lamps, in the dust of an unpaved square. This is a history told through stuff—the kind of history practiced by Walter Benjamin, whose Arcades Project was a gigantic, unfinished attempt to contain the spirit of 19th century Paris in an archaeology of unremarkable fragments. It goes back to Marx. It goes back even further to Thomas Carlyle, who believed he could excavate a present-tense sense of the French Revolution by looking closely at its detritus.

Open-world games tell both kinds of history at the same time. In their central narratives, they emphasize the agency of significant people; in their extensive worldbuilding, they emphasize city life, accidental encounters, objects, architecture, and economic exchange. Perhaps the most evident example of this schizoid structure is Assassin’s Creed III, widely panned at its release for both the absurd Gump-likeness of its central plot, and the proliferation of its side activities. In the same game where you, as the assassin Connor Kenway, invisibly assist the Founding Fathers in the creation of the United States, you can go hunting, play period-appropriate board games, and carry smallpox victims through the New York streets. You can pretend to dictate history; you can also pretend to live in it.

In Hail, Caesar!, the Coens’ jaunty recent meditation on studio filmmaking at the height of the studio system, we watch as a swords-and-sandals epic about ancient Rome springs forth from the very structure of the studio that produces it. The place is run by a square-jawed exec named Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin), who barks orders around the lot, yet makes space throughout the day for family time and Catholic guilt; the picture depicts a square-jawed Roman centurion (George Clooney), who takes charge, leads an army, and yet—in its melodramatic climax—bends the knee before Jesus Christ. Not just a Great Man story, but a Great Man story about redemption emerges from a studio culture built around the idea of its executive.

One can imagine how the duality of open-world games might emerge from the duality of the studios that create them. They arise from developer environments where a narrative vision shared by a few (directors, writers, etc.) is grafted uneasily onto the efforts of legions of talented people who are told simply to make stuff—tables, buildings, realistically animated chickens. It’s a kind of incoherence reflective both of the postmodernity of games, and the postmodernity of our thinking about history in general. The past itself is chaotic, open to infinite (and equally ideological) avenues of interpretation. Open-world games capture that, whether they intend to or not.

But this also reveals the immaturity of videogames made on this scale: the way they do so little to question, or manage, or think through their own expansiveness. The way they reach for totality and end up grabbing incoherence. The way they grasp unthinkingly for every mode of representation they can, not respecting that every mode of representation proclaims a worldview from the inside.

There is one big, beautifully coherent exception: Red Dead Redemption.

///

“I am living in history. I am not afraid to die.” Luisa’s line is unsettling for a few reasons. It feels out of context: she says it not at the climax of a heroic deed, but in a lull between missions, almost casually. It also doesn’t feel at all like a line written by the writers at Rockstar, who tend to make their characters (and, in a lot of ways, their games) into repositories of cynical, overwritten “social commentary.” Think of the high school-nihilism of a character like Jimmy De Santa, or GTA V’s (2013) Trevor spouting dialogue that sounds like bad Tarantino or Bill Maher’s standup. Of course, Marston responds to Luisa with cynicism of his own: “Your nobility’s almost as affecting as your naivety,” he says. But then she fires back: “I would rather be dead than a cynic like you, Mr. Marston.” And it becomes clear in this moment that the game might be cynical, but it has more than cynicism on its mind.

Luisa does an awful lot to change history, turning the tide of the revolution from a position of enormous disempowerment. Nonetheless, as she recognizes, she is a figure consumed by history, rather than an agent propelling it forward; it’s impossible to step outside, to direct without being directed. What makes Red Dead Redemption special is that it places the protagonist—and, by extension, the player—in the same position. The game’s plot illustrates this position in brutal clarity, almost at every turn. Marston is on a personal quest to locate and kill the outlaws he used to run with. His long, winding journey weaves into—and often affects—larger narratives of social and geographical transformation: political upheaval, technological expansion, the taming and assimilation of the West under the law and order of the East. But he’s also doing everything because he has to, because he’s a prisoner of the US government, and an instrument of its power. In every mission, with every gunshot, he works to destroy what he himself represents; he is not a spirit of justice, but a spirit of coerced self-corrosion. He makes history bend further in one direction, but it isn’t a direction he can ever decide.

“We can’t fight change,” his greatest nemesis tells him, before jumping off a cliff. “Our time is past.”

exploration is presented as a task never quite finished without systematic murder

One of the game’s more imaginative achievements is called “Manifest Destiny.” You get it by exterminating all the buffalo that roam the Great Plains, which never respawn. It’s both a stupidly on-the-nose joke and an impressively concise encapsulation of how the game as a whole marries its pervasive air of futility—and finality—to a player experience that emphasizes freedom and endless accumulation. Open-world games are seldom about things that end, things that become lost, or expansiveness that extinguishes life; their design stresses limitlessness, both in terms of what the player can do and what the player can be. You can join every guild in Skyrim (2011); you can keep sinking other ships in Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag (2013) until you have over a billion reales and you’re the seventh “Most Feared Pirate” on the North American leaderboard (this is literally true of my father-in-law). Red Dead knows. But it also overshadows every killing spree, every algorithmically-generated skirmish, every property purchased, with a claustrophobic sense of encasement: the very freedom of these movements only points toward a larger form of imprisonment. Marston is living in history, and history is ready to use him up and leave him behind.

Then again, he’s also a revolver-toting superhero who can nail six shots on horseback from 100 yards away. But even that brutal efficiency is a kind of passivity in the larger scheme of things, the larger scheme that Red Dead tries to depict in Super Panavision. The irony of “Manifest Destiny” evokes Butcher’s Crossing, a 1960 novel by John Williams (not that John Williams) that centers on a buffalo hunt in 1870s Kansas. The novel’s protagonist, Will Andrews, is a transplant from Boston who comes to the West seeking nature with a capital N—the sublime virginity of the landscape, celebrated and theorized by what characters in Red Dead call “those nature writers from back East.” He joins a hunt led by a man named Miller, a capitalist of beguiling, Daniel Plainview-like intensity. As the hunt proceeds, Andrews realizes that it bears more than a passing resemblance to the world of industrial production he has left behind. Miller shoots the bull and the others do not run; they stand in place and mill about, waiting to be culled with systematic precision, shot after shot, like the outlaws that populate Red Dead’s knee-high walls. The novel suggests that there is no escaping into the landscape from the great churning machine of commerce and exploitation. There is only bringing the machine with you.

Red Dead makes a similar argument through the constant, almost seamless shifting between its horseback riding and gunplay. In one moment, you’re travelling into a vast landscape drawn and quartered by telephone poles, yet still inviting in its inhumanity. In the next moment, you’re enacting inhumanity of another kind, dropping entire platoons with quick lever-like pulls of the left and right trigger. These are not tonally or conceptually disjunctive activities, which is what tends to happen in games (e.g. Uncharted) that try to graft shooting sequences onto exploration. Instead, they’re intertwined: systematic murder often lurks on the other side of exploration, and exploration is presented as a task never quite finished without systematic murder. The game uses its own open-world formula—in which roaming and machine-like slaughter necessitate each other like two parts of a rhyming couplet—to embody, rather than simply depict, the logic of American expansionism. Like the buffalo, Marston is a victim of that logic. But he’s also, in a sense, its avatar. It isn’t quite that history is ready to leave him behind; it’s that he can’t leave history behind—he can’t avoid being complicit in its destructive thrust.

A late mission finds Marston manning a Gatling gun in the back of a truck, driven through the streets of town by cackling federal agents who know—by virtue of the truck and the gun—where the arc of history is bending. He ends up killing a lot of people with that gun: mainly outlaws and Native Americans. But before he does, the agents drive him past crowds of people who look upon the contraption in awe and horror: “My oh my, that’s the devil’s work!” He’s in the backseat of an ugly death machine, chugging forward with grim inexorability. He can’t do anything, and you can’t either. But the game puts you, the player, in a position like Benjamin’s Angel of History, only looking forward rather than backward. For the time of that procession, you can imagine with horror where this thing is going to go. After all, it’s 1910.

///

One thing that late 20th century theorists of history tend to emphasize is that history is a story like any other, based not only in language (and therefore culture, and therefore ideology), but also in the conventions of genre. In his landmark 1974 study Metahistory, Hayden White pursues this larger point by arguing that many works of history make sense of their raw material—such as dates, facts, and sources—by organizing it via “emplotment.” That is, by shaping history into a culturally recognizable genre like tragedy, romance, satire, or farce.

At its most basic level, any history starts out as a “chronicle,” or a list of events organized into a chronological timeline. “The king went to Westminster on June 3, 1321,” is one such example. But a chronicle doesn’t have a beginning, middle, and end, nor does it include relationships of cause-and-effect. Almost organically, the historian shapes it into a “story,” telling us why the king went there and how his arrival started a war. Almost organically, that story is shaped to fit the mold of other stories that have been told before.

In Metahistory, White notes that many historical narratives make meaning out of their source material by shaping it into romance, a kind of quest narrative that presents not only “the triumph of good over evil,” but the hero’s personal transcendence over the injustices that shape the world. Other historical narratives opt for satire, which is antithetical:

The archetypal theme of Satire is the precise opposite of this Romantic drama of redemption; it is, in fact, a drama of diremption, a drama dominated by the apprehension that man is ultimately a captive of the world rather than its master, and by the recognition that, in the final analysis, human consciousness and will are always inadequate to the task of overcoming definitively the dark force of death, which is man’s unremitting enemy.

This “diremption” is what Red Dead Redemption is all about. It’s at the core of the game’s narrative of coerced self-destruction; it’s at the core of the gunplay and horseplay that results, often in the word “DEAD” in all caps on a blood-red screen. It’s as uncaring as Dark Souls’s “YOU DIED,” but even more impersonal. It’s right at the surface of dialogue shouted between horses during Sorkinian walk-and-talks: as the quack anthropologist Harold MacDougal says to Marston, riding alongside him, “You know, I dreamt of documenting the last days of the Old West. The romance, the honor, the nobility! But as it turns out, it’s just people killing each other.”

In this way, Red Dead Redemption shares a lot more in common with the “revisionist Westerns” or “anti-Westerns” that first arose in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, rather than the old Hollywood Westerns of the ‘40s and ‘50s. Those were products of the Eisenhower era; these were products of Vietnam. Those were about honor, justice, and the beckoning freedom of the landscape; these were about de-romanticizing the West, presenting it as a space of nihilism and brutality, in a kind of cultural reaction-formation to decades of American triumphalism. The game draws heavily on the bloody amorality of Spaghetti Westerns and the almost unbearable pessimism of Cormac McCarthy. It draws heavily on an evolved template for the genre that is itself, like Marston, self-reflexive and self-destructive. Revisionist Westerns tend to be about how the West isn’t the West you think you know—how that was a fantasy of the mythic past, a way of smearing Vaseline over history as it really was. They’re historical and historiographical at the same time, always reminding you why the kind of story they are telling is better than the kind of story they aren’t. Of course, that doesn’t automatically make the story true.

What makes Red Dead true may well be the way it puts forward an even greater, even more unremitting “enemy of the human”: history itself—or rather, the intoxicating desire to control it, get out in front of it. MacDougal is one of several characters in the game, including the Pancho Villa-like Reyes, who believes he can step outside and “document” the world he lives inside, the world of which he is hopelessly a constitutive part. Marston doesn’t believe he can, and we end up directly experiencing how right he is, with every massacre pursued at the behest of forces larger than himself. The game uses the illusory freedoms of its design to bring us face-to-face with illusory freedoms of a larger kind. It’s like BioShock (2007) in its self-consciousness about the ability of games to control their players; it’s a lot more powerful for never saying what it’s trying to do. It’s like no other open-world game in its way of preaching historical humility in the guise of simulated power—meditating beneath an experience of openness upon the enclosure of change and the gravity of time.

///

This article first appeared in Kill Screen’s relaunched magazine, Issue 9, which you can buy right now!

The post From the magazine: Red Dead Redemption, Reviewed appeared first on Kill Screen.

A short video on how to make videogame spaces for storytelling

How does a videogame introduce story to the player? Better yet, how does a game invoke emotion in the constrained physical world space of a game? We’ve seen it done in ham-fisted fashion: see the much maligned “Press F to Pay Your Respects” from Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, or consider the traditional “fight the baddies now pause for some story” route that many other big-budget games go.

“We’re creating an architecture for a story to exist in”

In a video from the Future of Storytelling series, Dear Esther (2012) director Dan Pinchbeck talks about how games often take for granted one of the most important spaces in narrative design: the player’s imagination. In the games created by the Chinese Room—games like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015) or Dear Esther—the player is given space to roam and walk around, experiencing the story and connecting with it as a part of the holistic flow of the game, rather than having it tacked on as a separate additional mechanic.

“We’re not just telling a story, we’re creating an architecture for a story to exist in,” he says. What game makers need to do, he opines, is make space not just for the player physically, but emotionally and creatively as well. Allow the player to create their own stories and fll in the gaps, even in games as directly linear as the ones created by the Chinese Room.

You can see the whole Future of Storytelling video here. The Future of Storytelling festival takes place on October 7-9th in New York. Find out more on its website.

The post A short video on how to make videogame spaces for storytelling appeared first on Kill Screen.

My experience as a virtual war photographer in Battlefield 1

Heterotopias is a series of visual investigations into virtual spaces performed by writer and artist Gareth Damian Martin.

///

What makes a battlefield different from any other place? Our towns, cities, fields, and parks are all potential battlefields, with lines of sight, choke-points, defensible terrain and no man’s land, all waiting to be activated. But how do you design a battlefield, balance the distribution of buildings, the flow of landscape, the arrangement of forms?

It started as an investigation. I would trawl the lone map of Battlefield 1‘s open beta to try to catalog the space custom made for its warfare. Stripping the game of its HUD and dropping into match after match, I would risk the wrath of my team to wander around, looking at the layout.

What I found was a surprisingly simple series of volumes, settled in a wandering landscape. The clustered houses and ruins seemed transparent—obvious high grounds and vantage points, peppered with windows for snipers to peek out of—while the sands of Sinai Desert provided little bubbles of action, separated by the peaks of dunes. Muddied with detail and complexity, these spaces took on differing atmospheres that shifted like the light over the precisely observed rocks of this arid terrain. The images I produced seem to reflect this simplicity, a quiet, composed set of shots, where landscape, sun, and shade dictate the parceling out of space.

Yet, as the battles blindly raged on around me, I began to find that this carefully composed landscape underwent a transformation. The artillery liberally spaced around the map, the bombers rumbling overhead, the grenades thrown inhuman distances to land in courtyards and on rooftops began to hammer out new spaces. Frames emerge, with the shattered edges of exploded masonry at their fringes.

the same architecture deconstructed in different ways

What was an initially disappointing series of boxy volumes became a dynamic architecture, always changing as I ran for cover, finding a hole where one wasn’t before, and a wall crumbling onto me. Over the course of multiple games on the same map, the process became one of recombination: the same architecture deconstructed in different ways. As a photographer, my scope widened, each explosion a possibility, each shattered wall offering new viewpoints, new lines of sight.

But there was something off about my distant examinations of space, my intention to catalog this battlefield as a series of changing sight-lines and barriers. After all, it’s the action, the event which makes a battlefield what it is. So I began to follow the combat, to track individual soldiers, ducking and circling around them to try to get the right angle for my shot.

When they threw themselves into a foxhole I was there with them. When they picked off targets from a first story doorway I was beside them. When they fell I was often next. I started to build a relationship to my subjects, carefully watching their cautious paths through the battlefield, their frantic charges across the sand. And it was there that a shot suddenly emerged, one that I knew had a wider connection the moment I took it. It was a Robert Capa tribute, a pastiche of one of the most recognizable war photographs of all time.

Death of a Loyalist Militiaman, taken by Robert Capa in 1936, is an infamous image. Taken during his time covering the Spanish Civil War, it shows a man at the moment of death, suspended mid-fall, his arms thrown out from his body, his gun rolling from his hand. My shot somehow mirrors that image, and yet it could not be more distant. There is no death in this image, no suffering. Only the onset of a frictionless machine of warlike imagery. Rather than confirm my experiment in war photography my accidental re-staging of Capa’s famous work seemed to question it, undermine it. In comparison to his image, mine is unreal, without real risk or drama. It is an empty copy.

And yet there is a connection; the process that created the image in the first place. After all, Capa’s work is not a masterpiece of framing and carefully considered lighting: he wasn’t even looking when he took it. It is instead an image created by an embodied practice, a process of being there, at that moment, and capturing something.

Most screenshots are bloodless things. They are taken using developer tools, free cameras, tweaked lighting and custom textures. Often, they are taken on unplayable versions of the game, carefully modified. Sometimes they are taken in spectator modes and then photo-shopped to appear more real, more authentic. There is nothing wrong with this, it’s just the way these images are produced. They have very little in common with the practice of shooting on a real camera. But I had no access to spectator mode, no cinematic camera. Instead, I had the ability to turn off the HUD and the ability to perform a melee attack, which, when timed correctly, cleared the screen of my characters weapon and hands.

I tried to capture something particular about the strangeness of this place

So when I took the image above my I was there, at least, as there as the soldier in front of me. I was dodging the shots that rained down from the peak of the dune, trying to line up my frame, taking cover among the sand. I had a single chance to capture this moment, a single aligned second. I am not fashioning myself as a digital Capa, or some great artist. But the process of capturing this image was something different, something new. It was something I had not experienced before in my time taking screenshots. A sense of danger (albeit imagined), a sense of capturing something dynamic, active, and a sense—one very familiar to a photographer—of a fleeting moment that, if not captured, would be hard to return to once more.

Robert Capa famously said “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Its a piece of advice I took to heart. I threw myself back into the battlefield, now seeing it as a space of potential encounters, of people play fighting, outsmarting each other, getting frustrated, getting lost, getting beaten. I didn’t try to capture what I thought a World War I photograph should look like, instead I tried to capture something particular about the strangeness of this place, where biplanes entwine with each other and fall to the ground, horses stand silently while tanks rumble past, and bodies disappear in seconds, meaning you have to be quick to catch them, or all that will be left is a helmet and a gun lying on the virtual sand of this manufactured, bizarre battlefield.

The post My experience as a virtual war photographer in Battlefield 1 appeared first on Kill Screen.

Paul Verhoeven’s latest film is about the struggles of a female videogame CEO

Warning: the content of the video included is NSFW and contains references to sexual violence.

///

At the start of Paul Verhoeven’s latest film Elle, a woman is violently raped. The rest of the story is about how that woman, a French videogame executive played by Isabelle Huppert, deals with her relationship with the rape and the rapist himself.

If the Verhoeven films you’re most familiar with are RoboCop (1987) and Starship Troopers (1997), Elle will surprise you. It’s perhaps a better fit in the realm of Verhoeven’s psycho-sexual thriller Basic Instinct (1992). That it is not immediately what it seems—a drama about a woman coming to terms with her own attack (a la Jodie Foster’s 2007 The Brave One)—but rather takes the concept and skews it attests to that. IndieWire, who saw the movie premiere at Cannes, called it a “lighthearted rape-revenge story.” This is not all too surprising: Verhoeven is best known for taking concepts in a provocative direction. B-movie level science fiction schlock turned into a commentary of fascist governments and propaganda? Check. A rape revenge dark comedy? Check.

Verhoeven is best known for taking concepts in a provocative direction.

There’s a long history of rape-revenge films and their questionably feminist legacy. “Many viewers/critics see the rape revenge film as only a small step above the slasher film, a sub-genre devoted to the humiliation of women but is nevertheless hidden behind the somewhat transparent banner of feminism,” Kier-La Janisse of Cinema Sewer writes. It’s easy to hate a rapist so it’s common shorthand for making you hate an antagonist, as well as allowing for titillation which is the meat and potatoes of schlock. It seems a very Verhoeven thing to do; to take a sub-genre defined by both its abuse and empowerment of women, and to attempt to reinvent it for the modern era.

With the threats of sexual assault that have perforated the videogame community, a film like Elle has the potential to run into a “ripped from the headlines” Law and Order: SVU vibe. The protagonist runs a videogame studio, she stands over a meeting wherein a violent rape is played out in pixels on screen. But she isn’t any of the women whose lives have been afflicted by the promises of sexual violence.

She’s not even like the women in the rape-revenge films that filled grindhouse theaters in the ’70s—though a former lover intones “the real danger, Michele, is you”—and she’s intentionally crafted to be difficult to pin down. Huppert, the star, says that the movie shouldn’t be seen as realistic, that instead it’s “a particular story about this woman as an individual, not women in general.”

Elle is set for release on November 11.

The post Paul Verhoeven’s latest film is about the struggles of a female videogame CEO appeared first on Kill Screen.

Hue is here to make you appreciate colors again

The sky is blue. That much we can agree on. Or can we? I mean, where I reside in San Francisco, it’s typically an ominous shade of grey (because, fog). In the clever new platformer Hue, from Fiddlesticks Games, the sky doesn’t have to be blue. Not always at least. The sky can be crimson red, fuchsia, purple, orange, lime green, and a couple of other tones. And it’s necessary to change—that’s at the heart of this game’s challenge. As you trek through its base-grey world, you must manipulate the sky to different colors to make various objects both appear and disappear to progress.

In the game you play as a small boy aptly named Hue. His white beady eyes peak out of the equally bleak and sometimes-technicolored world. He’s plagued to remain within this hauntingly default-grey universe. A world that’s full of terrors at every corner, where grim death animations of hopping into spikes resemble those of the desaturated Limbo (2010). All along his journey, Hue busily collects color fragments, aiding him in his quest to find his long lost mother (who has left behind saddening audio diaries about her ill-fated research and her raising of Hue away from society and the University she once worked).

Hue eases you into its puzzles, with only a couple of colors at your disposal. As the game moves onward and more shades join your wheel, the puzzles ramp up in difficulty. Before I knew it, I’d find myself sitting on a plane, hand stroking my chin, as I tried to plan my way through a particular screen. The puzzles in Hue are the perfect balance of difficult; sometimes dependent on timing, others on pure strategy, sometimes even both. I hardly found myself coasting through sections, nor tossing my controller in frustration and mumbling obscenities to a non-existent higher power. Figuring out the color-addled portions is part of the joy to be had in Hue.

Each new color represents a new mood

While color is used in Hue to solve puzzles, it also evokes a mood. Specifically in the quieter sections of the game, soundtracked merely by Hue’s mom’s monologues. Each new color added to Hue’s color wheel represents a new mood for his narrating mother, like red fostering her anger. In Masaaki Yuasa’s award-winning, sorta time travel-oriented anime The Tatami Galaxy (2010), color is also used as an indicator for different moments and emotions in life, as the protagonist pursues his coveted “rose-colored campus life.” When color filters over a scene, it’s likely to include his evasive love interest Akashi. Some scenes are blanketed in a shade of cherry blossom pink, others in a sublime yellow or green. Colors represent the different ways the protagonist’s friendship with Akashi exists—and how it’s manifested in different ways over the many parallel lived-in realities he experiences over the course of the show.

Hue has made me enjoy color in ways I haven’t in recent times, kind of in the same way that watching The Tatami Galaxy made me take a step back from my isolating lifestyle and try to enjoy life. Back when I was art director for my measly university’s magazine, I obsessed over hues and complements, making sure all colors were perfect in our pages at all times. In Hue, color isn’t just the center of a challenge, it presents a new way to see the world at hand. A new way to experience the colors in both our virtual and everyday lives. Who knows, maybe I’ll go outside today just before sundown. Perhaps the sky will be a light mixture of pink and orange, rather than the grey I’m used to. There won’t be any puzzles at my disposal, but that’s okay, the color will enough to see. Beyond just another glowing computer screen.

Explore the saturated world of Hue for yourself. It’s available now on Windows, Mac , PS4 , and Xbox One for $14.99. It’s also coming to PS Vita… eventually. And if you’re colorblind, fear not! Luckily there’s a togglable colorblind option, in which symbols appear over their corresponding color.

The post Hue is here to make you appreciate colors again appeared first on Kill Screen.

Starbound rockets you back to childhood

Socrates asserted that “man must rise above Earth to the top of the atmosphere and beyond, for only then will he fully understand the world in which he lives.” This sentiment is at least in part why NASA was established, and why investments are made in “NASA’s grand dream.” It’s why Elon Musk’s SpaceX was able to raise over $1 billion for spaceship manufacturing from companies like Google, with rocket rides for the public booked out for years. And maybe it’s why many of us, as kids, couldn’t help but stare up at the vast, velvet expanse of the night sky, watching the stars glimmer, and wonder, “What else could possibly be up there?”

Space is the final frontier, after all. So perhaps it’s only natural that even at a young age, humans are predisposed to an inexplicable fascination with exploring and inhabiting the mysterious void that lies beyond Earth. It’s here, at this point, that Starbound zooms in, a game that wants to grant your wildest imaginings, science fiction without the leash. Yes, it says, there are bazooka-wielding penguins and little gnome people up in space. Go and find them.

It’s a game that wants to give you a lot, maybe even everything

Childhood wish fulfillment is the defining element of Starbound. Finn “Tiy” Brice, the project leader of the game, even called Starbound his “dream game,” one that captures the charm of 16-bit classics and throws it all into a blender with vast numbers of vivid, randomly generated worlds. It’s a game that wants to give you a lot, maybe even everything, but above all it emphasizes and encourages classic exploration. This is done, in part, by making it almost too easy, as with just a little time and effort you can stumble upon uninhabited bungalows surrounded by bizarre fauna, jungles of pink-leafed tentacle-shaped trees, or other such fascinating settings, all available just beyond the cold hunk of metal that is your spaceship. I even found a rare, playable violin worth a lot of pixels—the game’s currency—simply by exploring a fungus-filled cavern for a few minutes. The game provides uncountable discoverable treasures like this, all of them contained in a sandbox that bears many similarities to the one provided in Re-Logic’s Terraria (2011). Which makes sense: Tiy was, in fact, the lead artist on Terraria.

That grand aim of Starbound’s is ubiquitous. And so, not only does it want you to be able to do anything you like, it wants you to be able to do it as whoever you want to be. To this end, the character customization is uncomplicated: you can choose hair style and color, clothing style, and skin tone. But you can also choose what race you are. And it’s there that Starbound starts to show its own personality, providing a unique spread of seven races that could only be the brainchild of someone high on sugary Lucky Charms or, I don’t know, Galactic Crunch. By way of example, the Novakids: glowing cowboy-esque humanoids composed of solar gases, contained by a supercharged metal brand—usually star-shaped—smack dab on their face. And each different race provides you with a characteristic armor bonus. My own character was an Avian, a bird-like humanoid that dwells in forests, and her armor bonus provided me the ability to glide. Because why the hell not.

I grew to become quite fond of my weird little Avian character and her two-handed rocket launcher, not because she was particularly strong, but simply because, in Starbound, I got to play as a freaking bird with a rocket launcher. Meanwhile, my friend deeply bonded with his weapon, a giant Erchius eyeball that shot out terrifying laser beams from its blood-red pupil. Really, there’s a race, a hair style, a weapon for everyone here, and Tiy has clearly ensured that his game would create no boundaries for self-expression. In that way, Starbound manages to avoid the issues of other procedurally generated games—games that eschew the charm and personality of handcrafted design for random generation—by giving the player a chance to play as God and impose their own personality and style on the game.

Starbound avoids the issues of other procedurally generated games by giving the player a chance to impose their own personality and style

Starbound’s strive to give you complete freedom isn’t always a boon, though. In fact, the start of the game is disorienting for the very fact that it gives you so much independence. For example, the game begins when a horde of gargantuan tentacles (of course) envelope earth, forcing your character to make a rapid escape on a commandeered spacecraft that quickly crash lands on a new planet. Your AI companion gives you a list of objects to acquire to repair your ship—in this case, core fragments—but doesn’t provide you with information about where to get those items. The lack of orientation results in a slow and frustrating beginning to the game, one that is further accentuated by the logical questions that will pop into your head. Questions like: How long is it going to make my new ship not look like a rusted ol’ piece of junk? How long is it going to take until I find cool weapons? How long will be before for the story becomes compelling, if there even is a story? These questions itch at the back of your mind and, for some, may turn into a reason to abandon the game for good.

But, at the same token, it’s impossible to ignore that it’s that same lack of orientation that has you realize that there are no rules and no questions, only play. The game solves its openness by throwing absurd action your way. It’s like as soon as you dwell too long on what to do, Starbound thinks it fit to send a band of space pirate penguins to raid you. Tiy has said, the game is to be played more as a fun, social experience rather than just a single product: “Our goal in developing the game,” he told Curse, “was for the players to always find something new, every time they play.” I didn’t even realize I could capture and tame wildlife until several days of play, and once it dawned upon me that I could swing from ropes Indiana Jones-style, well, spelunking in outer space suddenly became an option. On top of these small discoveries, the game is both procedurally generated and filled with community-generated content, meaning that there’s potentially no end to the surprises you can stumble upon. If childhood is about discovery, then Starbound succeeds in emulating it, dropping you into a place where wonderment abounds, where rules and logic and narrative can all be tossed out the space shuttle window, if you so desire.

That brings me to the planets that you can discover in Starbound, which for the most part, look nothing like ones I’ve seen before. I’ve searched for comparisons in other science fiction and come up empty. This is perhaps where the fact that the game is procedurally generated really comes into its own. These aren’t worlds reminiscent of those seen in Star Wars, or Stargate, or Dune. Starbound manages to differentiate itself from the usual planetary tropes, in part because it banks on its near-absurd childlike imagination, but also due to allowing its players to create entire communities on their servers to reflect their particular interests. The effort is stretched to each planet’s culture, as you can examine every object—decorations like pots and hanging furs on the wall—to learn about a certain homeowner through detailed descriptions. It goes further: each species has its own unique set of NPC interactions so that your understanding of each planet’s culture is piecemeal. That means that every time you play, you can adventure episodically, like the cast of Star Trek, to explore a new, unpredictable variation of a planet and the secrets it hides.

Playtime waits for no one

Once, while turfing a new planet, my friend found a weapons chest that gave him a fantastic sword upgrade from the get-go. I checked the same place in my game and found only dirt (I’m not bitter, I swear). To assuage my jealousy, and to stop my temper tantrum, we started playing in multiplayer mode. I learned something that day: fighting enemies alone in Starbound is hard. It’s not just the number crunch that makes it so, it’s the alienness of its randomized rules that catches you off guard. For example, one enemy took on the form of a turtle, I thought it would be slow-moving. Nope. This isn’t Earth—Starbound likes to subvert expectations at every turn. With another player in co-op, Starbound’s combat moves firmly in the direction of ridiculousness, especially as you’re barking orders at each other about the need to avoid, of all things, damned penguins driving huge tanks, as if it were a weird game of Pretend. As we learn when we are young, playtime is best experienced with a friend, and Starbound seems to have been made with this as its mantra.

If Starbound has one major downside it’s that there is no pause button. A pithy consideration, I know, but it means if you’re exploring a cavern found deep within the recesses of a new planet, you cannot pause to take a much-needed bathroom break. And since enemies can spawn at any time, you can’t walk away from your computer in confidence, either. But the lack of a pause button almost feels apt: in Starbound, there can be no pause button, no way to suspend you from this childhood fantasy. To pause would be to remind you that, in the end, Starbound is just a game—that you are an adult, likely with responsibilities and distractions back on Earth. And like your childhood friend, the game doesn’t want you to leave: there’s just too much to show you, too much for you to find, and too much to explore. Playtime waits for no one. You wanna get up to pee? Nope, you’ll have to sit there and do the wiggle dance, holding it in. Just like when you were a kid.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Starbound rockets you back to childhood appeared first on Kill Screen.

N++ knows you can go faster than that

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

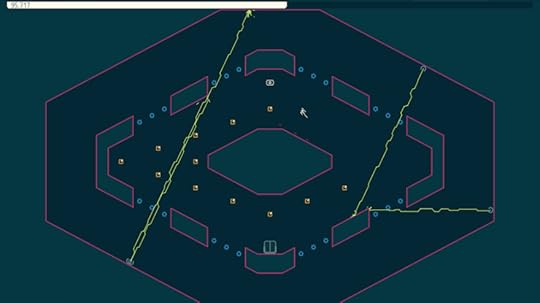

N++(Windows, PlayStation 4)

BY METANET SOFTWARE

There hasn’t been an N game on PC since the first one back in 2004. Now the second sequel, N++, has arrived on its home platform (it’s also available on PS4). While it is a sequel, N++ is better considered a version of the original game that’s been refined and tweaked over the course of a decade. It’s a momentum-based 2D platformer as before, one that has you collecting gold squares while dodging missiles and darting past robots. But it feels smoother and more confident in its design: the physics are smoother, which makes mastering the art of balancing speed and inertia all the more satisfying. It also offers a huge number of handmade levels for you to beat—2,360 to be precise—and then replay to submit a better time to the global leaderboards. It also comes with a level editor so, if you get through those, you can make your own or try out those made by other players.

Perfect for: Parkour fans, the competitive, level designers

Playtime: 10 hours (and a whole lot more)

The post N++ knows you can go faster than that appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers